An Integrated IT-Architecture for Talent

Management and Recruitment

Christian Maier

1

, Sven Laumer

1

and Andreas Eckhardt

2

1

Centre of Human Resources Information Systems, Otto-Friedrich University Bamberg

Feldkirchenstraße 21, Bamberg, Germany

2

Centre of Human Resources Information Systems, Goethe University Frankfurt a. Main

Grueneburgplatz 1, Frankfurt a. Main, Germany

Abstract. Already in 2001 Donahue [7] argued in her Harvard Business Re-

view article that it is time to get serious about talent management and in 2005

Hustad and Munkvold [11] presented a case study of IT-supported competence

management. Based on Lee’s suggested architecture for an holistic e-recruiting

system [16] and the general research on e-HRM the aim of this paper is to sug-

gest an integrated IT-Architecture for talent management and recruitment fol-

lowing the design science guidelines proposed by Alan Hevner [10] to support

both the recruiting and the talent as well as competence management activities

of a company.

1 Problem Relevance

A recent study by the Boston Consulting Group and the World Federation of Person-

nel Management Associations suggests that “People have emerged as a new source of

competitive advantage. Consequently, the demand for skilled people is rising at the

same time that shortages abound” [24]. This clearly demonstrates the problems that

will in future have to be faced by businesses, and above all their personnel depart-

ments. Since, on the one hand, increasingly fewer people are available because of

Germany’s demographic situation and, on the other because of a lack of suitable

training, there will be a shortfall of about 1.2 million academically trained personnel

by 2020, it will become even more difficult to recruit competent staff [20]. Neverthe-

less, it is precisely this highly qualified staff that will be needed to ensure a sustaina-

ble competitive advantage over competitors in the long term [21]. As a consequence,

personnel development and personnel retention are becoming, next to recruitment, the

main focuses of the responsibilities of the personnel department. The importance of

these disciplines is also made clear in the annual survey produced by [19]. They in-

vestigate among other things the major challenges faced by the Chief Information

Officers of top American companies, and “attracting, developing and retaining IT

professionals” were top of the list for the first time in their 2007 study [19].. The

latter includes not merely the recruitment of new staff but also the development of

their capabilities and their long-term retention in the company [11, 12, 17]. This

Maier C., Laumer S. and Eckhardt A. (2009).

An Integrated IT-Architecture for Talent Management and Recruitment.

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Human Resource Information Systems, pages 28-38

DOI: 10.5220/0002173700280038

Copyright

c

SciTePress

process is also known as “talent management” which can be defined as the manage-

ment of the supply, demand and education of talent within an organization [23].

To deal with these problems, HR processes can call on the support of new elec-

tronic media [5, 6, 8, 25]. There has already been an initial approach to a holistic

scheme for electronic (E-) recruitment processing designed by [16], which enables

swift electronic access to a pool of applicants.

The aim of this paper is to build up step-by-step an architecture which will ulti-

mately support both recruitment and personnel development processes by means of

appropriate systems. This architecture is intended to take into account the various

different reasons for which a company might wish to develop and train its staff.

We structure our paper for this purpose following the principles of Design Science

[10]. In Section 1 we briefly outline the relevance of this topic to the basic problems

against the background of the demographic situation and the shortage of well quali-

fied staff. Section 2 contains a review of the literature on various personnel develop-

ment processes, an E-recruitment system, fundamental research results about compe-

tence as well as a short explanation of the approach of Design Science. In Section 3

we describe the steps in the development of an IT-architecture for personnel devel-

opment which is ultimately integrated with [16] recruitment system. In the last sec-

tion we summarize the most important results and indicate both the limitations of this

architecture as well as areas in which there is scope for further research.

2 Research Rigor

2.1 Design Science

Design Science, the research method proposed by [10] in 2004 is an extension of

behaviorist methodology. Behaviorism attempts to predict what effects the introduc-

tion of IT within organizations will have with the aid of theoretical propositions.

Within the Design Science framework artifacts which can be employed within busi-

nesses to solve problems are developed and evaluated. For the implementation of this

framework, seven guidelines which should be followed to use the principles of De-

sign Science in the field of information systems (IS) are presented [10]. In this paper

we will develop our IT-architecture following these guidelines.

2.2 Personnel Recruitment

Before we explain Lee’s 2007 approach [16], we first describe the individual

processes that are fundamental to personnel recruitment.

2.2.1 Individual Personnel Recruitment Processes

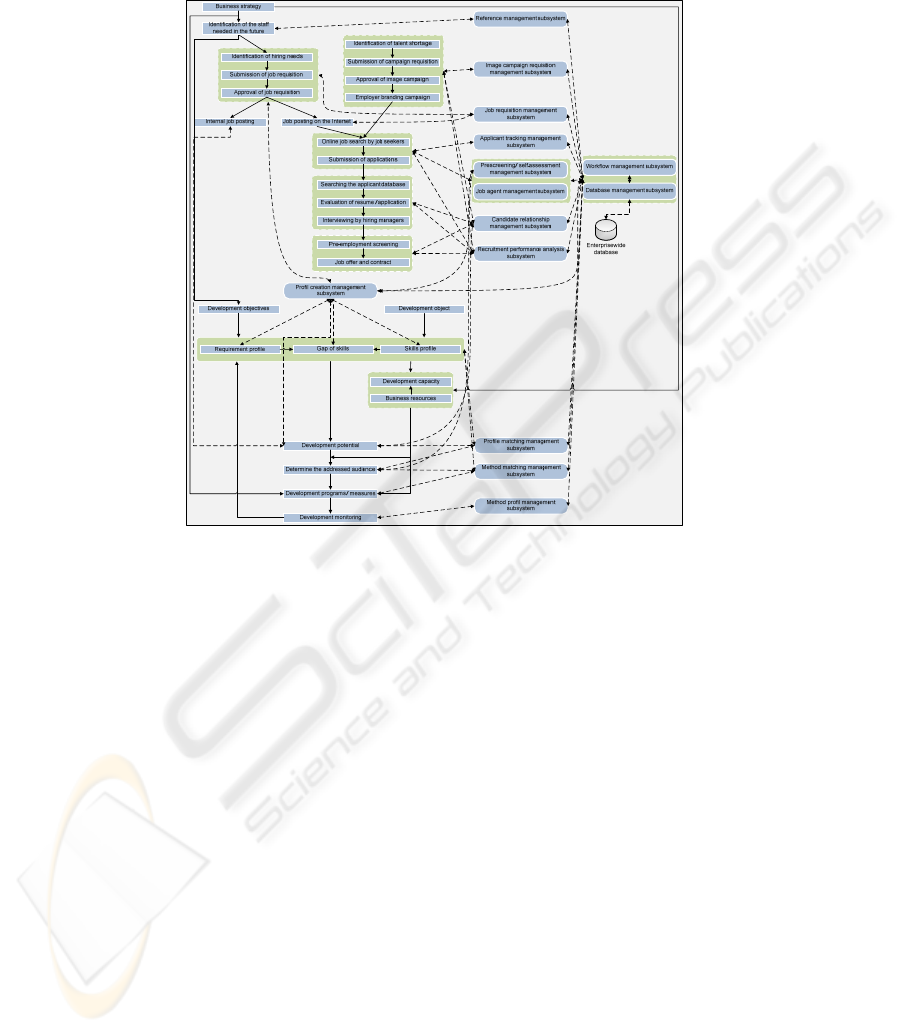

As one can see from the left-hand side of figure 3, it is necessary at the beginning of

the recruitment process to discover what a company’s future personnel requirements

will be. Then the skills that the new personnel must have are input, communicated

and authorized before the job advertisement can be finally published [6]. At the same

29

time job-seekers can search through an online database and submit their applications

directly. After the personnel department has searched the database (DB) for candi-

dates, their applications are evaluated and initial interviews are held. Finally, the

company negotiates a contract with the chosen candidate, so that the recruitment

process reaches a conclusion that is satisfactory for both parties. [16]

2.2.2 e-Recruitment System

To implement the processes explained in the preceding section Lee [16] developed an

e-recruitment system. This requires 8 sub-systems, which can be seen on the right-

hand side of figure 3. Lee’s paper will give a more detailed presentation of the more

broadly relevant systems and their purposes. We will use this proposed IT-artifact to

develop an integrated architecture for talent management and recruiting. Since we

would like to base our work on the most up-to-date knowledge in discussing the IT-

architecture in Section 3, [15] have extended Lee’s initial suggestions to include the

steps of the Employer Branding process: Please consult their suggested architecture

for more details [15].

2.3 Personnel Development Processes

One way of combating vacancies in companies is the process described above, that is,

acquiring outside personnel for the company. On the other hand, the required person-

nel can also be acquired internally by selecting members of the company’s current

staff and preparing them suitably for their new responsibilities [7]. To do this, it is

often necessary to introduce training measures which will enable staff to develop their

capabilities [4, 7]. The concept of personnel development is, however, characterized

by “great heterogeneity and lack of clarity” [2] (p. 2). As a result, we find a large

number of definitions of personnel development in the literature.

To provide a consistent understanding of the concept of personnel development in

the sections that follow, we base ourselves on the definition of [9], who regard per-

sonnel development as a function of personnel management, whose aim it must be to

provide all members of staff with training and qualifications enabling them to carry

out both present and future tasks. In the process those individual capabilities of the

personnel which serve the achievement of the company’s goals should be encour-

aged. This positive alteration in the qualifications of the staff is understood as a

process consisting of a series of several linked activities [9].

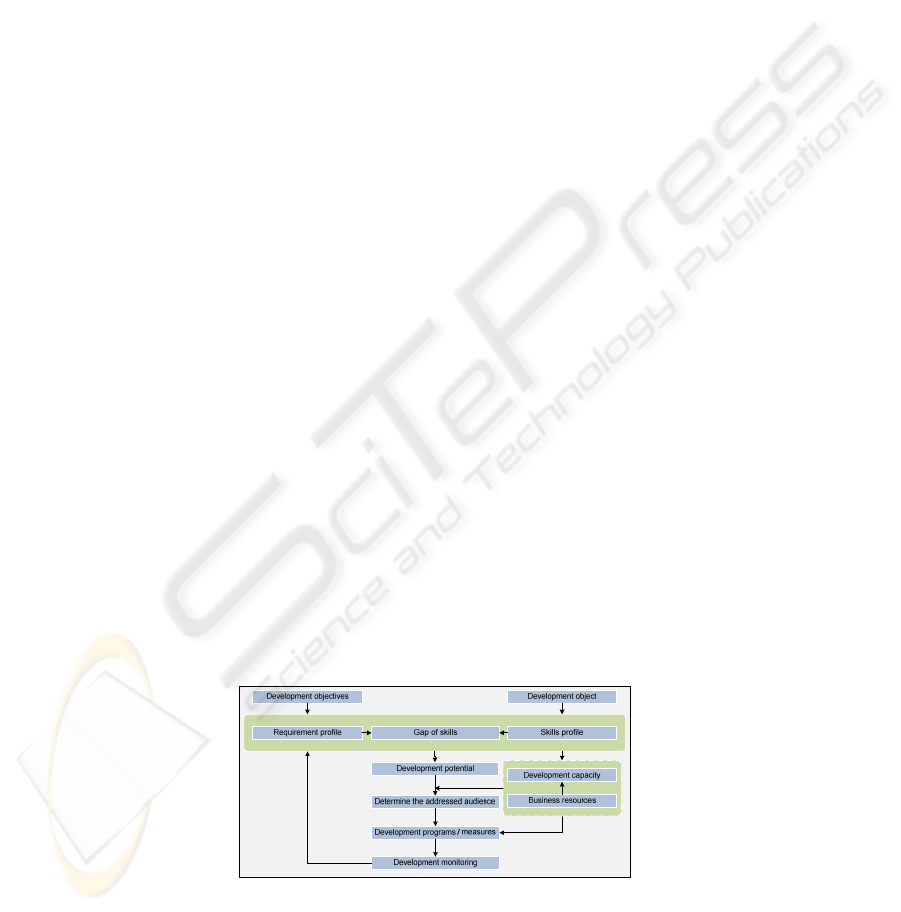

Fig. 1. Personnel Development Process (Source: [22]).

30

Since, as described in Section 3, a company may have several different reasons for

developing the capabilities of its staff, we have chosen from the literature a personnel

development process which supports this aim. Such a process is defined by [22], as

represented schematically in Figure 1. In this process the gaps in the capabilities of

each employee are deduced from the difference between their ‘capability profile’ and

the profile of requirements defined by the company. This reveals how suited an em-

ployee currently is for a given job. Building on this, those employees who are eligible

to take part in development activities but have not yet been able to acquire compe-

tences that are available are given a deadline for completing the relevant training.

Frequently an employee’s entire potential cannot be fully exploited because the com-

pany only has limited resources available. After successful completion of a training

program the ‘capability profile’ is updated and checks are carried out to see whether

the employee now satisfies the conditions of the required profile and/or whether the

training program actually provides the desired competences [22].

2.4 Competence

In order to select candidates for vacant posts or training programs from within a com-

pany, it is desirable to store their qualifications long-term in a database in order to

have quick access to them.

In recent years there have been a number of publications dealing with the themes

of competence, competence catalogues or competence management [14]. To be able

to provide a structure for the competences available in a company, a classification is

set up. [1] suggested in this context that the parameters should be subject, methodo-

logical, human and social competence. To avoid ambiguity within the classificatory

scheme, competence catalogues set out “a tested vocabulary for competence that is

used on all occasions where competence plays a role” [14] (p.2). The individual com-

petences of each employee must also be evaluated. Accordingly, mention must be

made for each employee of how strong each individual competence is. Various re-

search programs recommended the use of a five-point, and therefore uneven, scale

[18], in spite of the problems caused by a tendency to prefer the middle element too

frequently [13]. As well as permitting a finer distinction between grades of compe-

tence because of the neutral centre, this also makes it possible to avoid making direc-

tional decisions in cases of indecision or when a competence is absent [3].

3 Design as a Search

3.1 Determining Future Personnel Requirements

As can be seen in Figure 2, the company first investigates how high the future de-

mand for personnel will be. To make an informed decision, those responsible has

access to data from previous periods, since the decisions made here will have far-

reaching consequences and are also influenced by many complex factors. For exam-

ple, the company’s fundamental strategy has to be taken into account. If the company

31

plans expansion, new branches or sites, a merger or something comparable, then its

long-term personnel requirements is adapted to suit this. The state of the national

economy also plays an important role.

Thus in times of positive economic growth the company needs to quickly take on

new staff in order to fulfill orders successfully, or when a recession threatens, work-

ers must be made redundant to avoid excessively high monthly fixed costs. When the

company has discovered its future personnel requirements, the difference between

these and the current staff situation must be calculated. Depending on this result, the

personnel department can look for new staff, prepare staff for new projects by train-

ing, downsize or just leave everything as it is.

3.2 IT Systems for Internal Personnel Recruitment Processes

3.2.1 Fundamental Procedures

In this section we consider what occurs when a company selects qualified, internally

available staff and promotes them, optionally preparing them for their new duties by

means of training programs. The company can follow this path if no suitable external

staff can be employed or if to do so would be too expensive.

Identification of the staff

needed in the future

Current staff Determined staff

Gap

Recruit staff Dismiss staffDevelop staff

Economy Business strategy... ...

Enterprisewide

database

Age distribution

Fig. 2. Overview of Personnel Management Tasks.

Firstly, candidates for these posts, who fit the requisite job-profile or at least come

close to it, must be identified among the current staff. In order to do this a require-

ment profile for the post that is to be filled must be defined. If a similar profile is

available in the DB from previous recruitment campaigns, it can be reused. Otherwise

a kind of dummy-employee with the optimal competences for the vacant post is en-

tered into the ‘Profile Creation Management Subsystem’ (PCMS). The capability

profiles of all actual employees are defined in terms of their current competences and

should be consulted in the DB at each step when new posts are being filled, and up-

dated if necessary. For both profiles a five-point scale is used because of the advan-

tages described in Section 2.4. In the requirement profile it seems most sensible to use

the neutral element if a particular competence is not relevant to the vacant post; we

would also use the two positive values on the scale to define how strong the compe-

tence should be for an employee to be best able to carry out the tasks. In our opinion

the two negative elements should only be used in extreme cases. This is more closely

specified in a unified way for the whole company in the underlying catalogue of

competences. The competence definitions should also be provided here.

32

Next, a system is needed to work out the variance between the requirement profile

that has been defined and each member of staff. As described in Section 2.2.2 the

PSMS has is required to perform similar tasks during the recruitment process. The

similarity between employee profiles and requirement profile must now be tested not

only for those who have applied for a post, but also for all members of staff.

Which candidate can now be considered for the post also depends, as explained in

2.3, on whether the company has resources available for personnel development.

3.2.2 Internal Recruitment without Previous Personnel Development

If the company does not have sufficient resources available at present to train em-

ployees for the new post, it is possible, using the PSMS as shown in Figure 3, to de-

termine, on the basis of the capability gaps of each employee, which one has the most

of the competences required.

3.2.3 Internal Recruitment Preceded by Personnel Development

It is more advantageous for the company if resources are available to prepare the

selected candidate as well as possible for the new post by means of a training pro-

gram. As well as the index value calculated in Section 3.2.1, the development poten-

tial of each employee should also be taken into account in the choice of candidate, as

shown in Figure 3. We do not consider here whether the company determines this

potential by expert judgment or by portfolio techniques, since both procedures have

their advantages and this also depends on company size and the capital available [22].

These results are then entered in the relevant capability profile under social compe-

tences using the PCMS, and should once more be classified company-wide in a uni-

fied way using a 5-point scale (cf. Section 2.4). Additionally it is possible to have a

justification of this decision available in the profile in the form of a running text, so

that the previous decision will be comprehensible in future tests.

In order to filter out the best qualified candidate, distinguished by both present

competences and also a high level of development potential, an index value is calcu-

lated in the ‘Profile Matching Management Subsystem‘ (PMMS). Other components

can also contribute to this calculation.

When the most suitable candidate has been found, the ‘Method Matching Man-

agement Subsystem’ (MMMS) is used to determine the training program best suited

to providing them with the competences they do not yet possess. For this purpose all

available training programs, together with the competences which attending each of

them will improve, must be stored in the company-wide DB. First one could extract

from the PSMS those competences which the candidate does not have but needs in

order to best carry out the duties of the new job. Then the MMMS will call up all

possible training programs which could communicate the missing competences to the

employee. This could be done using simple Information Retrieval methods.

Finally spot checks could be carried out to see if the training programs do actually

produce the required competences. After analyzing the results, conclusions could be

reached about what competences had actually been achieved. By comparison with the

employee’s previous competences, the training program can be subjectively eva-

luated. In general, several case studies should be stored in the DB, each of which tests

33

different specific competences. These studies should be available to the trainers by

means of the ‘Method Performance Management Subsystem’ of the DB, into which

the trainer can then enter the results of the work on the case studies after evaluation.

Finally, the trainees are entered into or extracted from the MMMS so that their up-

dated competence profiles can be stored in the database.

3.3 IT Systems for Personnel Development Processes

Since it is not always absolutely necessary to train personnel and then directly pro-

mote them, this section will describe two other possible modes of proceeding.

3.3.1 Personnel Development for Reasons of New Strategic Orientation

It is sensible to initiate training programs when a company, for example, changes its

long-term strategy, thus requiring new competences in the company. If the company

plans off-shoring, then it is clearly desirable from the company’s perspective that

some employees should learn the new language and its culture in order to enable

better communication between the different locations and so that people mutually

understand and respect each other’s cultures.

The order to do this by developing training programs which suit their strategy can

come directly from the company management, who are also responsible for creating

the strategy. This can be stored in the DB together with the competences it requires,

so that the various sub-systems have access to it.

This could be carried out in a way analogous to the approach suggested in Section

3.2, in that selected employees could be directly promoted so that they could then

oversee a project or a similar activity long-term in the new location. Courses which

improve the general level of education of the staff could also – at least, if the compa-

ny’s resources permit – be open for all to attend, which could be achieved using the

architecture described in Figure 3. Since these offerings are made use of by relatively

few employees, they would not result in such high costs.

3.3.2 Anticipatory Development of Missing Competences

Companies may find that they very frequently have a shortage of employees with

particular competences. With the approaches used until now, one either had to recruit

personnel with these capabilities, which is expensive, or use time-expensive courses

to train employees who would only be available to the company after successfully

completing their training.

The company could use the procedure illustrated in Figure 3 to train employees in

a purposeful way even if there were currently no acute demand for this. If a require-

ment profile with these previously rare competences were then sought, suitable can-

didates would immediately be available in the company. To identify the competences

of which there is a frequent shortage, access to all requirement profiles used so far

must be made possible. No matter whether jobs are advertized internally or external-

ly, the job profile and the relevant competences should be permanently stored by the

PCMS in the DB.

34

Since the required competences are consistently stored in a system, the sub-system

only stores additionally how often any given profile or competence was required by

the personnel department. This provides the PCMS with yet another responsibility,

that is, not only that the personnel department enters and stores specific profiles, but

also that it should be possible by means of this sub-system to discover how high the

demand for particular competences and profiles has been in a given period.

If there are as yet no training programs to develop the most frequently required

competences, the company can offer new or supplementary training in the light of this

knowledge. Then specific employees can be selected by the personnel department

using the process described in 2.2 and can then be offered the opportunity, for exam-

ple by electronic means, to take part in this training without paying.

3.4 Integration of the Personnel Recruitment System and Development

System

Since we have now shown several different possible ways of implementing systems

in the area of personnel development, we would like to explain now how they can be

integrated with Lee’s architecture [16].

As shown in Figure 2, the starting point should be the top management since they

determine the direction of personnel recruitment and development by means of the

strategy they lay down. As described in section 3.1, deciding how many personnel to

employ and what competences they should have in the future is a difficult process.

For that reason the company should retain the decisions made in the past, the envi-

ronmental or industrial factors that prevailed at the time as well as the results of those

decisions in the ‘Reference Management Subsystem’. If this information is also kept

subjectively by several employees, the business has supplementary information about

which activities might be useful in the future. Optionally, one could also record

measures which, seen retrospectively, were not as successful as they might have been.

This decision now influences the way recruitment and personnel development sub-

sequently proceed. Since we have already explained both architectures individually,

we now intend to discuss only those sub-systems which can be seen as interfaces

between these two approaches.

This shift in responsibilities makes sense, since the architecture becomes more

flexible as a result and it is possible for companies to introduce only those sub-

systems which support individual critically important processes. This also makes it

clear that it is profiles, consisting of competences, that should be stored at the compa-

ny-wide level and not, for example, the exact formulations of job advertisements. The

latter could optionally be stored alongside every competence profile in the DB, but it

is the competence profiles that are decisive when defining index values or compe-

tence gaps. The PSMS is also needed both to support personnel recruitment

processes and to ensure that personnel development processes run as efficiently as

possible. The tasks necessary for achieving this have already been explained in sec-

tions 2.2.2 and 3.2. It is also possible to observe the employees’ development poten-

tial long-term and continuously. This can be done with the help of the CRMS by

extending the tasks originally described in Section 2.2.2. Using the CRMS one could

build up lasting contact with particular employees, and in the process observe their

35

development. From this process one could derive indicators showing whether these

employees would in future be capable of taking on more responsibility.

Fig. 3. Integrated IT Architecture for Personnel Recruitment and Development Processes.

4 Communication of Research

4.1 Limitations

It should be noted that the architecture suggested is so far based only on a literature

review. Thus there has been no validation by case studies or empirical assessments

which would make it possible to quantify its actual usefulness. First ideas of an IT-

supported competence management system can be find in a case study at Ericsson

[11]. One should also consider the aspects to which [16] has already called attention.

He made it clear that his e-recruitment system is expensive and complex. Expanding

this architecture increases the costs for realizing the whole concept as well as the

complexity, and thus a company must decide for itself which elements of the architec-

ture to introduce. This can be decided within the company in the light of the expected

benefit, and depends among other things on what resources are available in the com-

pany, what branch of industry it is active in, how big the company is, as well as on

the company’s strategy for the future, depending for example on whether they intend

to benefit from the advantages of being a ‘First Mover’. Apart from this it should be

noted that the architecture can essentially be used in any country or any industry.

36

4.2 Suggestions for Further Research

Future research should initially establish exactly what benefits this architecture pro-

vides. It would also be possible to extend the architecture. Thus, for example, the

systems used until now could support the career planning of individual employees

and clearly show well-trained employees what their career prospects are. Here we are

approaching the idea of personnel retention, which is also not considered in the cur-

rent architecture. The PMMS and MMMS sub-systems can also be seen as recom-

mender systems for which algorithms could be devised.

4.3 Research Contributions

Because of the anticipated future shortage of qualified staff, companies will, above

all, have to develop their current personnel in order to be able to generate a lasting

competitive advantage over their competitors on the basis of their workforce. To

enable this, we have presented a comprehensive IT architecture, based on the Design

Science approach [10], which integrates recruitment processes with personnel devel-

opment processes, supporting them with several different sub-systems.

References

1. Bader, R., Entwicklung beruflicher Handlungskompetenz in der Berufsschule. 1990, Soest,

Landesinstitut für Schule und Weiterbildung.

2. Becker, M., Personalentwicklung. Bildung, Förderung und Organisationsentwicklung in

Theorie und Praxis. Vol. 4. 2005, Stuttgart, Schaeffer-Poeschel.

3. Bortz, J. and N. Döring, Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation. 1995, Berlin, Heidelberg,

Springer.

4. Cappelli, P., Talent Management for the Twenty-First Century. Harvard Business Review,

2008. 86(3), p. 74-81.

5. Dineen, B.R., J. Ling, S.R. Ash, and D. DelVecchio, Aesthetic properties and message

customization: Navigating the dark side of web recruitment. Journal of Applied Psycholo-

gy, 2007. 92(2), p. 356-372.

6. Dineen, B.R. and R.A. Noe, Effects of customization on application decisions and appli-

cant pool characteristics in a web-based recruitment context. Journal of Applied Psycholo-

gy, 2009. 94(1), p. 224-234.

7. Donahue, K.B., Time to Get Serious About Talent Management. Harvard Business Review,

2001. 79(7), p. 6-7.

8. Hendrickson, A.R., Human Resource Information Systems: Backbone Technology of Con-

temporary Human Resources. Journal of Labor Research, 2003. 24(3), p. 381-394.

9. Hentze, J. and A. Kammel, Personalwirtschaftslehre. 7th ed. 2001, Stuttgart.

10. Hevner, A.R., S.T. March, J. Park, and S. Ram, Design Science in Information Systems

Research. MIS Quarterly, 2004. 28(1), p. 75-105.

11. Hustad, E. and B.E. Munkvold, IT-Supported Competence Management: A Case Study at

Ericsson. Information Systems Management, 2005. 22(2), p. 78-88.

12. Kleine, J., Talentmanagement. Werben um die Manager von morgen., in Focus. 2007,

Hamburg.

37

13. Korman, A.K., Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 1971, Englewood Cliffs, New

Jersey, Prentice Hall.

14. Kunzmann, C. and A. Schmidt, Kompetenzorientierte Personalentwicklung. ERP-

Management, 2007. 3(1), p. 38-41.

15. Laumer, S. and A. Eckhardt, What makes the difference? Introducing an Integrated Infor-

mation System Architecture for Employer Branding and Recruiting, in Handbook of Re-

search on E-Transformation and Human Resources Management Technologies: Organiza-

tional Outcomes and Challenges, T. Bondarouk, et al., Editors. 2009, Information Science

Reference.

16. Lee, I., The Architecture for a Next-Generation Holistic E-Recruiting System. Communica-

tions of the ACM, 2007. 50(7), p. 81-85.

17. Lindgren, R., D. Stenmark, and J. Ljungberg, Rethinking competence systems for know-

ledge-based organisations, in European Journal of Information Systems. 2003. p. 18-29.

18. Lissitz, R.W. and S.B. Green, Effect of Number of Scale Points on Reliability: A Monte

Carlo Approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1975. 60, p. 10-13.

19. Luftman, J. and R. Kampaiah, Key Issues for IT Executitives 2007. MIS Quarterly

Executive, 2008. 7(2), p. 99-112.

20. McKinsey&Company, Deutschland 20|20. Zukunftsperspektive für die deutsche Wirtschaft.

2008, McKinsey & Company, Frankfurt.

21. Pfeffer, J., Producing Sustainable Competitive Advantage Through the Effective Manage-

ment of People. Academy of Management Executive, 2005. 19(4), p. 95-108.

22. Scholz, C., Personalmanagement: Informationsorientierte und verhaltens-theoretische

Grundlagen. 5th ed. 2000, München.

23. Schweyer, A., Talent Management Systems - Best Practices in Technology Solutions for

Recruitment, Retention and Workforce Planing. 2004, John Wiley & Sons.

24. Strack, R., A. Dyer, J. Caye, A. Minto, M. Leicht, F. Francoeur, D. Ang, H. Böhm, and M.

McDonnell, Creating People Advantage: How to Address HR Challenges Worldwide

Through 2015, in BCG Publications. 2008.

25. Strohmeier, S., Research in e-HRM: Review and implications. Human Resource Manage-

ment Review, 2007. 17, p. 19-37.

38