SOCIAL ROBOTS, MORAL EMOTIONS

Ana R. Delgado

Universidad de Salamanca, Avda. De la Merced 109-131, 37005 Salamanca, Spain

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Contempt, phenomenology, Moral emotions, Social robots.

Abstract: The affective revolution in Psychology has produced enough knowledge to implement abilities of emotional

recognition and expression in robots. However, the emotional prototypes are still very basic, almost

caricaturized ones. If the goal is constructing robots that respond flexibly, in order to fulfill market demands

from different countries while respecting the moral values implicit in the social behavior of their

inhabitants, then these robots will have to be programmed attending to detailed descriptions of the

emotional experiences that are considered relevant in the interaction context in which the robot is going to

be put to work (e.g., assisting people with cognitive or motor disabilities). The advantages of this approach

are illustrated with an empirical study on contempt, the seventh basic emotion in Ekman’s theory, and one

of the “rediscovered” moral emotions in Haidt’s New Synthesis. A phenomenological analysis of the

experience of contempt in 48 Spanish subjects shows the structure and some variations –prejudiced, self-

serving, and altruistic– of this emotion. Quantitative information was later obtained with the help of blind

coders. Some spontaneous facial expressions that sometimes accompany self-reports are also shown.

Finally, some future directions in the Robotics-Psychology intersection are presented (e.g., gender

differences in social behavior).

1 INTRODUCTION

“Our most ardent emotions are evoked not by

landscapes, spiders, roaches, or dessert, but by other

people.” (Pinker, 1997; p. 396)

Humanoid robots are being constructed with

various uses in mind. Evolutionary inspired

psychological research, which reverse-engineer

emotions, can be very useful to decide what

emotions must be programmed in order to reach the

relevant goals in different situations. If social robots

are to be created, then moral emotions should be

simulated, given that each one of these emotions

seems to be, among other things, the solution to a

social exchange problem from our evolutionary past

(Cosmides & Tooby, 2005).

My first proposal is that current psychological

theories on morality can help engineers to decide the

“proper” emotions for different human-robot

interaction situations by taking into account both the

evolutionary roots of each emotion and the

functionality of that emotion in the current

interaction context.

Impressive as they are, abilities of emotional

recognition and expression in robots are still very

basic ones. My second proposal is methodological:

in order to know the structure of emotional

experiences, descriptive phenomenology (also

known as heterophenomenology) can be of great

help. We can agree in that animation design and

robots that are to be marketed in a specific culture or

in a particular population stratum must take into

account people’s particularities. Thus, after deciding

what emotions need to be programmed, a detailed

description of the experiences and facial expressions

of people from the target culture or population

stratum in everyday life should be obtained for the

selected emotions. This is exactly what descriptive

phenomenology is useful for.

2 SOCIAL ROBOTS

Social robots are being constructed so that their

dispositions or behaviours take the interests,

predicted intentions or needs of human beings into

account.

According to Salichs et al. (2006), the long-term

goal of the most part of research in Robotics is to

develop a social robot that can interact with humans

263

R. Delgado A. (2009).

SOCIAL ROBOTS, MORAL EMOTIONS.

In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - Artificial Intelligence and Decision Support Systems, pages

263-270

DOI: 10.5220/0001830202630270

Copyright

c

SciTePress

and participate in human society. This type of robot

must have effective and natural interfaces with a

high level of robot autonomy. There are various

robotic platforms that have been built to study

human-robot social interaction. Kismet is probably

the most popular one (Breazal & Brooks, 2005).

Other social robots are RUBI (Fortenberry, Chenu

& Movellan, 2004), Feelix (Cañamero & Fredslund,

2001), and Maggie (Salichs et al., 2006), to cite just

a few.

It is important to note again that social behavior

and moral emotions are intrinsically related. Known

to the researcher or not, moral values are implicit in

many social customs. Obviously, it is not easy for us

to perceive how it works in our own culture, given

that we are part of it, and so the implementation of

capabilities of expression and recognition of the so-

called moral emotions in robotic platforms could

also help to make explicit some values that are

implicit in the social interaction but sometimes

remain unseen even for the trained eye.

2.1 Human-Robot Interaction

Evolutionary inspired research shows that the

human selective sensitivity to features in the human

face that convey information on sex, age, emotions,

and intentions is applied not only to other human

beings or animals, but also to artificial structures,

such as cars. (Yes, others do it too!) When people

are asked to report the characteristics, emotions,

personality traits, and attitudes they attribute to car

fronts, automotive features and proportions are

found to covary with trait perception in a manner

similar to that found with human faces (Windhager

et al., 2008). There is a consistent association

between certain emotion expressions and the

inference of some personality traits that designers

had implicitly known and used –e.g., from the

expression of contempt, together with some postural

gestures, people make the inference of shyness

(Arya, Jefferies, Enns & DiPaola, 2006). In

animation design and Robotics, this information is

useful to create affective production systems.

Cañamero (2005) has reviewed the reasons why

it would be convenient to have robots with affective

capabilities. A common (and reasonable)

assumption in the field is that displaying emotions

and recognizing and responding appropriately to the

emotional states of humans will make users more

prone to accept robots and engage in interactions

with them. In fact, expressive facial animation

synthesis of human-like characters is already being

approached with good results (see, e.g., García-

Rojas et al., 2006).

In the Artificial Intelligence field, researchers

have devoted much effort to solving the problem of

emotion recognition and expression; psychological

and even neuropsychological theories of most of the

basic emotions –fear, sadness, surprise, happiness,

anger, and disgust– are well known by many, and so

I will not insist on them. I would just like to point

out that the communicative function of emotions

(Darwin, 1872), has been highlighted by Adolphs

(2006) as one of the two future trends in the

scientific study of emotion. (The other direction has

to do with the use of neural and psychophysiological

measures.)

Even though the instruments derived from Paul

Ekman's theory –such as the JACFEE test

(Matsumoto & Ekman, 2004)– have been decisive

in the scientific advances in the study of emotional

expressions, a methodological change leading to

more naturalistic, less caricaturized stimuli, is now

required. According to Adolphs (2006), context

effects and individual differences will have to be

taken into account in future research projects in the

Neurosciences, whose current procedures are

focused on very simple prototypes. Adolphs’s

suggestion could be applied to Robotics word for

word.

2.2 Moral Emotions

“People are selfish, yet morally motivated. Morality

is universal, yet culturally variable. Such apparent

contradictions are dissolving […]” (Haidt, 2007; p.

998)

Evolutionary theories inquiring into the origins

of morality have focused on the study of reciprocal

altruism (Cosmides & Tooby, 2005; Haidt, 2003;

Trivers, 1971), a strategy that can be biologically

successful only when participants have both the

motivation to cooperate and the motivation to avoid

or punish cheaters (Trivers, 1971).

Knowledge of the latest theories on the so-called

moral emotions is not common among AI

researchers. Actually, neither is it among

psychologists, given its novelty. Psychological

research on morality had traditionally focused on the

study of moral reasoning and on two of the moral

emotions: guilt and empathy. A simulation of

empathy seems to have been the dominant strategy

in social robotics. However, in the last few years,

increasing attention has been paid to other emotions

such as contempt, although the interest in anger and

disgust has somewhat obscured the role of

contempt. The CAD (Contempt, Anger, Disgust)

ICEIS 2009 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

264

hypothesis of Rozin, Lowery, Imada and Haidt

(1999), associates an emotion to each one of the

violations of community morality. Contempt is the

emotional response to the violations of duties

associated with some social hierarchy, while anger

and disgust are linked to violations of autonomy and

purity, respectively.

Actually, in Haidt’s New Synthesis, the

building blocks of human morality are the emotions,

and moral intuition is considered as previous to

moral reasoning. Various psychological

foundations, each with a separate evolutionary

origin, seem to support moral communities

constructed by human cultures. Moral reasoning can

override moral intuition, but it is usually performed

with social goals in mind, i.e., to avoid being the

target of gossip.

The study of the moral role of emotions such as

contempt, anger and disgust, typically considered as

negative, is one of the most novel and promising

fields in Psychology (Haidt, 2007).

3 ON CONTEMPT CONSIDERED

AS ONE OF THE MORAL

EMOTIONS

The expression of contempt, characteristically

asymmetrical, is the least studied of the basic

emotions in Ekman’s theory and the most variable

one with respect to cultural context (Elfenbein &

Ambady, 2002).

Miller (1997) has described the subtle ways in

which contempt serves in signalling and maintaining

distinctions of rank, which is consistent with the

CAD hypothesis. In hierarchical societies, contempt

is shown as an assertion of the lack of importance of

the other, who would not even deserve a strong

feeling such as anger. In more egalitarian societies,

however, contempt is felt for those who do not

measure up either to social position, or to the self-

claimed level of prestige. According to Miller

(1997), a common phenomenon in democratic

societies is “upward contempt”, such as the

contempt of students for teachers or daughters for

mothers.

From the scientific –not literary, philosophical

or legal – point of view, contempt has hardly been

investigated. In the context of emotion theories,

some authors had considered contempt to be a

variant of disgust (Ekman & Friesen, 1975), anger

(Lazarus, 1991), or a mixture of these emotions

(Plutchik, 1980). Ekman and Friesen (1986)

included contempt in their list of basic emotions,

and recent cross-cultural studies indicate that, when

a matching procedure is used, contempt is

recognized nearly as well as the remaining basic

emotions (Rozin, Lowery, Imada, & Haidt, 1999).

Thus, it seems that methodological factors were in

part responsible for the confusion between disgust

and contempt in previous studies.

More corroborating evidence can be found in a

recent neuropsychological experiment: disgusted

faces elicited greater activation than contemptuous

faces in the insula and contemptuous faces elicited

greater activation than disgusted faces in the

amygdala (Sambataro et al., 2006); the amygdala

seems to be especially involved in processing face

cues that are socially relevant.

3.1 Meaning and Use

There is no controversy concerning the meaning of

the term "contempt" (the Spanish "desprecio", the

French "mèpris", or the Italian "disprezzo"). It

implies a feeling of superiority over someone who is

negatively considered (Izard, 1977; Darwin, 1872,

Ekman & Friesen, 1986). For instance, the meaning

of the Spanish term has not changed for centuries, as

registered in the successive dictionaries of the

Spanish Royal Academy.

By using frequency as an indirect indicator of

the use of the term "desprecio", it has been found

that contempt is an especially salient emotion in

Spain, in contrast with other Spanish-speaking

countries. In a study carried out on a representative

corpus composed of 103,184 basic emotion terms

with the objective of deciding the verbal labels for

the seven basic emotions in Spanish, a consistently

ordered sequence was discovered –fear, sadness,

surprise, happiness, anger, contempt and disgust–,

both diachronically and synchronically (in

Colombia, Cuba, Chile, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru,

Puerto Rico, Spain, USA and Venezuela). Even

though consistency was nearly perfect, there was an

anomaly: in Spain, the Spanish term for contempt is

more frequent than the Spanish term for anger, that

is to say, contempt was the fifth and not the sixth

term of the ordered sequence, contrary to the rest of

the Spanish-speaking countries (Delgado, 2007).

Concerning action tendencies, contempt is a cold

emotion (Darwin, 1872; Izard, 1977), which makes

it easier for a robot to express it. Contempt does not

motivate fight or flight, but promotes cognitive

changes so that its object is treated in a less

considerate way in future interactions (Oatley &

Johnson-Laird, 1996). This is probably why

SOCIAL ROBOTS, MORAL EMOTIONS

265

contempt is usually evaluated as a negative emotion.

However, there might well be situations in which

people intuitively feel contempt for someone and

consider it the morally appropriate answer to a

social behavior (or lack of it).

3.2 The Experience of Contempt

“It seems to me that this is why, although statistical

methods were highly productive in early

experiments on animals, they rarely led to good,

new ideas about the levels at which only people can

think. This is why I want to emphasize the

importance of trying to classify the Types of

Problems that people recognize […]” (Minsky,

2006; p. 252)

Descriptive phenomenology is one of the

expanding methodological perspectives in

Psychology (Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003). The procedure

begins with a description of an experience to be

understood psychologically which is usually

obtained by means of an interview and becomes the

raw data of the research. Meaning units are first

established and later transformed into

psychologically sensitive expressions. Finally, the

structure is determined.

Lacking an external and objective measure of

emotional experience, the analysis of the patterns of

what people say about their feelings and mental

representations seems to be the best point of

departure. It is well known that self-reports do not

reveal causal information, but they are essential for

revealing the ontological structure of consciousness

(Barrett, Mesquita, Ochsner & Gross, 2007). Even

though “qualia” are not themselves causal, they are

informative indicators of causal core states; in fact,

conscious states are the only indicators we have of

any overall core state (Edelman, 2006).

3.2.1 Objective

The objective of this empirical reseach was to

describe the structure and some variations of the

experience of contempt by analyzing a corpus of

interviews, as well as showing spontaneous facial

expressions that sometimes accompany self-reports.

3.2.2 Methodology

Some forty-eight University students in their early

twenties volunteered as participants.

Data were saved on a MacBook by means of an

iSight webcam oriented to the participant (see in

Figure 1 how the screen is oriented to the

interviewer so that she can control the image). To

store, edit and analyze the videotaped interviews,

Quicktime and iMovie were used.

As to the procedure, participants were

interviewed about (a) their general idea of contempt,

(b) a typical contempt episode, and (c) a personal

episode. Later on, they fulfilled tasks of emotional

perception and production whose results are

reported elsewhere.

A descriptive phenomenological analysis was

then carried out in order to learn the structure of the

experience and categorize the answers following a

bottom-up, inductive approach. The general idea of

contempt was found to be composed of some

qualitative elements that could be coded as present

or absent and then added up to make a contempt

definition score.

Figure 1: A simple data-collection instrument.

Both the prototypical and personal episodes were

categorized by means of two concurrent category

systems each, describing the objects and reasons of

contempt. In order to avoid expectancy bias, results

were quantified with the help of two “blind” coders.

3.2.3 Qualitative Results

Contempt was associated to (a) an avoiding attitude,

(b) a negative experience, and (c) a feeling of

superiority, which is consistent with the

psychological literature on the topic, although the

avoiding attitude was mentioned more often than

expected for a “cold” emotion. In fact, rejection (or

some sort of avoiding) was the most mentioned

element, followed by the negativity of the

experience.

Contrary to descriptions of contempt as an

emotion that serves mainly in signalling and

maintaining distinctions of rank, superiority was the

ICEIS 2009 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

266

least mentioned element.

As to the prototypical episode, subjects often

described situations in which a person feels

contempt for another who has done something

wrong to a third party, i.e., altruistic contempt,

although contempt as prejudice was modal. Only

three participants told a story in which the motive

for contempt is self-serving (e.g., person A feels

contempt for person B who has done something

wrong to A).

Exemplar 1: feeling contempt for someone who

has bothered the subject.

Exemplar 2: feeling contempt for someone who

has commited a terrorist act.

Exemplar 3: feeling contempt for people of a

different race.

More variability was found for the personal

episode. Unexpectedly, many participants began

telling a story in which they were the “receiver” of

contempt (a fact that could be of clinical

significance). This is not semantically wrong, but it

is not what was wanted, and thus they were asked to

report an experience in which they were the

“sender” of contempt.

The phenomenological analysis shows that the

structure of the personal contempt experience is

mostly associated with situations in which someone

has done something wrong to the participant,

although situations in which contempt is felt for a

person who had done something wrong to a third

party or whose characteristics are disliked were also

described.

Exemplar 1: feeling contempt for a friend who

has despised me.

Exemplar 2: feeling contempt for a person who

has done something unfair to a third party.

Exemplar 3: feeling contempt for a person

because I dislike her clothing style.

Both the prototypical and personal episodes were

categorized by means of two concurrent systems

each, describing the objects and reasons of

contempt.

Concerning the object of contempt, the category

system divides the domain into three: intimate,

social and abstract.

As to the reasons for contempt, they are also

classified in threes: something that the object has

done to the subject of contempt, something that the

object has done to a third party, and something that

the object of contempt is (race, social role, personal

characteristics...). These reasons have been labeled

as self-serving, altruistic, and prejudiced,

respectively.

3.2.4 Quantitative Results

Two trained observers, blind to the objectives of the

study, used the previous systems to code the

transcriptions and get frequency data. Inter-observer

agreement was 97%.

When asked for their general idea of contempt,

participants responded with at least one term related

to a negative experience, an avoiding attitude or a

feeling of superiority. These elements were coded as

present or absent and then added up to make a

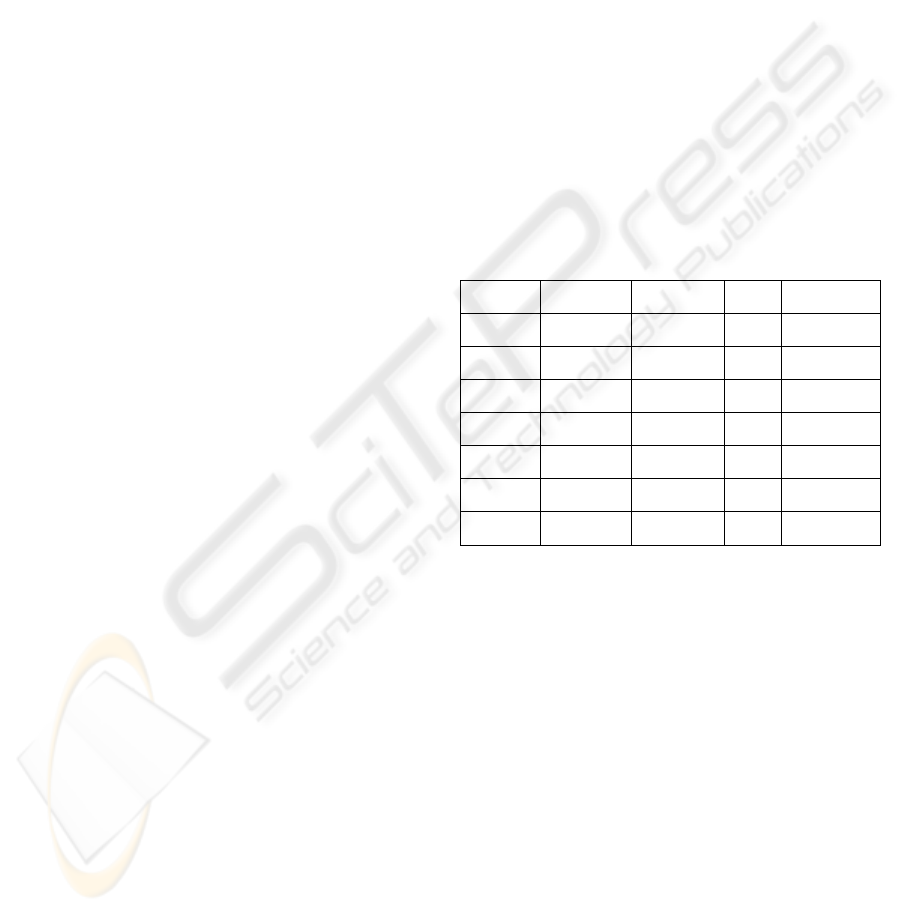

contempt definition score. Table 1 shows the

distribution of answers with one, two or three coded

elements, as well as the frequency distribution of

scores.

It can be seen that rejection or some kind of

avoiding attitude was the most mentioned element,

doubling in frequency the superiority aspect.

Table 1: Contempt Definition Elements and Score.

Avoiding Negativity Superiority Score Frequency

1 0 0 1 13

0 1 0 1 8

0 0 1 1 6

1 1 0 2 12

1 0 1 2 5

0 1 1 2 2

1 1 1 3 2

When describing a typical contempt episode,

65% of the subjects narrated events that can be

thought of as prejudiced, implying the feeling of

contempt for something that the other is (race, social

role, personal characteristics...).

Some 29% told episodes in which a person felt

contempt for another who had done something

wrong to a third, i.e., altruistic contempt. Notice that

the 95% confidence interval for this proportion goes

from .16 to .42, not including zero.

Table 2 shows that only three participants

attributed direct self-serving motivations to the

subject of contempt.

Abstract referents (a person, someone…) were

described by 85% of the sample, and only seven

subjects mentioned a contempt object with which

the subject had a social (but not intimate)

relationship.

SOCIAL ROBOTS, MORAL EMOTIONS

267

Table 2: Typical Contempt Episode: Reason by Object.

Intimate Social Abstract Total

Self-serving 0 0 3 3

Altruistic 0 0 14 14

Prejudiced 0 7 24 31

Total 0 7 41 48

When describing a personal episode, there was

more variability in the narrated events (see Table 3).

Two subjects insisted that they had never felt

contempt for anyone. Of the remaining forty-six,

half described self-serving situations in which the

objects of contempt were diverse (close friends and

loved ones were mentioned five times in this kind of

episode).

Table 3: Personal Contempt Episode: Reason by Object.

Intimate Social Abstract Total

Self-serving 5 8 10 23

Altruistic 1 3 7 11

Prejudiced 0 3 9 12

Total 6 14 26 46

Some twelve subjects (26% of the sample)

described episodes that can be coded as prejudiced,

and eleven, or 24% of the sample, described

altruistic episodes (the 95% confidence interval for

this proportion goes from .12 to .36, not including

0). The object of contempt was abstract in 57% of

the episodes, social in 30%, and intimate in 13% of

them.

3.2.5 Spontaneous Facial Expressions

Some participants showed clear expressions of

contempt while narrating their experiences. These

expressions are more ecologically valid than the

usual, posed ones.

The characteristical assimetry of contempt,

described by Darwin as “a slight uncovering of the

canine tooth on one side of the face” (Darwin, 1872;

p. 255), and considered by Ekman and Friesen

(1986) as a pan-cultural expression of emotion, can

be seen in Figure 2.

According to Darwin (1872), another common

method of expressing contempt is by slightly turning

up the nose, which apparently follows from the

turning up of the upper lip. This is the expression

showed by the participant in Figure 3.

Figure 2: A spontaneous contempt expression.

Figure 3: A spontaneous disgust-as-contempt expression.

Darwing himself indicated that mouth and nose

movements such as those in Figure 3, when strongly

pronounced, express disgust. Current emotion

classifications, not taking into account either the

intensity or the context of the expression, would

label Figure 3 as a disgust expression.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The structure of the contempt experience was

extracted from the analyses of answers to three open

questions. First, when asked for a definition of

contempt, participants responded with at least one

term related to a negative experience, an avoiding

attitude or a feeling of superiority. Rejection or

ICEIS 2009 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

268

some kind of avoiding attitude was the most

mentioned element, more than expected for a “cold”

emotion.

When describing a typical episode, subjects

seldom mentioned episodes related to reciprocal

altruism. More often, they narrated episodes in

which a person felt contempt for another who had

done something wrong to a third party, i.e., not a

self-serving situation, but an altruistic one.

However, experiences reflecting prejudice –feeling

contempt for something that the other is– were

modal.

Finally, when describing a personal situation,

there were mainly self-serving episodes that can be

related to reciprocal altruism, although both

prejudiced and altruistic contempt appeared in

similar proportions. It must be noticed that whether

the moral role of contempt is salient in subjects’

self-reports (and not only in the theorist’s mind) is

an empirical question for which this study has found

a positive answer.

These results are in concordance with Haidt’s

New Synthesis, in which contempt is the emotional

response to the violation of some social duties.

According to Haidt (2007) the moral domain of

educated Westerners is more focused on principles

of no-harm and fairness than it is in the rest of the

world. However there are still other psychological

foundations of morality; one of them, having to do

with intuitions of ingroup-outgroup dynamics and

the importance of loyalty, is clearly behind many of

the situations that have been described by

participants in this study. Moll, de Oliveira-Souza

and Zahn (2008) have proposed that truly moral

choices lie in doing something “right” (including

punishment or avoiding of norm violators) when

more immediate selfish motives would tell the agent

to do otherwise. There is usually no direct benefit in

despising terrorists or feeling contempt for people

who mistreat other people, and thus the conception

of altruistic contempt seems to be supported by our

data.

5 FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The next step is to begin new rounds of interviews

with other population strata, such as old people.

Following the trends in qualitative sampling, using

an extreme comparison group would help to falsify

(or else corroborate) conclusions on the structure of

the experience of contempt.

Pursuing the study of sex-related differences in

contempt is another unquestionable fruitful

direction, because morality theorists as well as

psychologists have found some such differences in

both morality and social communication (e.g., Hall,

2006; Jaffee & Hyde, 2000). Given our evolutionary

past, sex-related differences in social cognition have

also been predicted (Kimura, 1999; Geary, 2006).

Thus, the lack of differences in current studies could

be attributed to procedures not taking into account

contextual factors (Fischer & Roseman, 2007).

Other variables such as personality type could

also be taken into account in future studies. In any

case, it has been shown that it is possible to

investigate the moral concepts and expressions that

characterize a target group by means of a very

friendly procedure. This information should be of

use to those who wish to market more versatile

social robots while respecting the moral values

implicit in the customs of the target population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by MEC EXPLORA

action SEJ2007-29492-E. The author wish to thank

Felix Inchausti and Margarita G. Marquez for acting

as blind coders.

REFERENCES

Adolphs, R., 2006. Perception and emotion. How we

recognize facial expressions. Current Directions in

Psychological Science, 15, 222-226.

Arya, A., Jefferies, L.N., Enns, J.T., DiPaola, S., 2006.

Facial actions as visual cues for personality. Computer

Animation and Virtual Worlds, 17, 371-382.

Barrett, L. F., Mesquita, B., Ochsner, K. N., Gross, J. J.,

2007. The experience of emotion. Annual Review of

Psychology, 58, 373-403.

Breazal, C., Brooks, R., 2005. Robot emotion: a

functional perspective. En J.M. Fellous & M.A. Arbib

(Eds.), Who needs emotions? The brain meets the

robot (pp. 271-310). New York: Oxford University

Press.

Cañamero, L., Fredslund, J., 2001. I show you how I like

you: Can you read it in my face? IEEE Transactions

on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Part A, 31, 454–

459.

Cañamero, L., 2005. Emotion understanding from the

perspective of autonomous robots research. Neural

Networks, 18, 445-455.

Cosmides, L., Tooby, J., 2005. Neurocognitive

adaptations designed for social exchange. In D. M.

Buss (Ed.), Evolutionary psychology Handbook (pp.

548-627). New York: Wiley.

SOCIAL ROBOTS, MORAL EMOTIONS

269

Darwin, Ch., 1872. The Expression of the Emotions in

Man and Animals. London: John Murray.

Delgado, A. R., 2007. Spanish basic emotion words are

consistently ordered. Quality&Quantity. DOI:

10.1007/s11135-007-9121-3

Edelman, G.M., 2006. Second nature. Brain science and

human knowledge. London: Yale University Press.

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., 1975. Unmasking the face.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., 1986. A new pan-cultural

facial expression of emotion. Motivation and Emotion,

10, 159-168.

Elfenbein, H.A., Ambady, N., 2002. On the universality

and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A

meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 203-235.

Fischer, A.H., Roseman, I.J., 2007. Beat them or ban

them: The characteristics and social functions of anger

and contempt. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 93, 103-115.

Fortenberry, B., Chenu, J., Movellan, J., 2004. RUBI: A

Robotic Platform for Real-time Social Interaction.

Third International Conference on Development and

Learning (ICDL'04).

García-Rojas, A., Vexo, F., Thalmann, D., Raouzaiou, A.,

Karpouzis, K., Kollias, S., Moccozet, L., Magnenat-

Thalmann, 2006. Emotional face expression profiles

supported by virtual human ontology. Computer

Animation and Virtual Worlds, 17, 259-269.

Geary, D.C., 2006. Sex differences in social behavior and

cognition: Utility of sexual selection for hypothesis

generation. Hormones and Behavior 49, 273 – 275.

Giorgi, A.P., Giorgi, B.M., 2003. The descriptive

phenomenological psychological method. In P.M.

Camic, J.E. Rodes & L. Yardley (Eds.), Qualitative

research in Psychology. Expanding perspectives in

methodology and design (pp. 243-273). Washington,

DC: APA.

Haidt, J., 2003. The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K.

R. Scherer & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of

affective sciences (pp. 852-870). Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Haidt, J., 2007. The new synthesis in moral psychology.

Science, 316, 998-1002.

Hall, J.A., 2006. Women's and men's nonverbal

communication. Similarities, differences, stereotypes,

and origins. In V. Manusov & M.L. Patterson (Eds.),

The Sage Handbook of Nonverbal Communication

(pp. 201-218). London: Sage.

Izard, C. E., 1977. Human Emotions. New York: Plenum

Press.

Jaffee, S., Hyde, J.S., 2000. Gender differences in moral

orientation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin,

126, 703-726.

Kimura, D., 1999. Sex and cognition. Cambridge, MA:

The MIT Press.

Lazarus, R. S., 1991. Emotion and adaptation. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Matsumoto, D., Ekman, P., 2004. The relationship among

expressions, labels, and descriptions of contempt.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87,

529-540.

Miller, W. I., 1997. The anatomy of disgust. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Minsky, M., 2006. The Emotion Machine. Commonsense

Thinking, Artificial Intelligence, and the Future of the

Human Mind. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Moll, J., de Oliveira-Souza, R., Zahn, R., 2008. The

neural basis of moral cognition. Sentiments, concepts,

and values. Annals of the New York Academy of

Sciences, 1124, 161-180.

Oatley, K., Johnson-Laird, P. N., 1996. The

communicative theory of emotions: Empirical tests,

mental models, and implications for social interaction.

In L. L. Martin & A. Tesser (Eds.), Striving and

feeling: interactions among goals, affect and self-

regulation (pp. 363-393). Hillsdale, NJ: LEA.

Pinker, S., 1997. How the mind works. New York: Norton

& Company.

Plutchik, R., 1980. Emotion: A psychoevolutionary

synthesis. New York: Harper & Row.

Raouzaiou, A. Karpouzis, K., S. Kollias, S., 2004.

Emotion synthesis in virtual environments. In ICEIS

2004, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference

on Enterprise Information Systems. Porto, Portugal.

Rozin, P., Lowery, L., Imada, S., Haidt, J., 1999. The

CAD triad hypothesis: A mapping between three

moral emotions (contempt, anger, disgust) and three

moral codes (community, autonomy, divinity).

Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 76, 574-

586.

Salichs, M. A., Barber, R., Khamis, A.M., Malfaz, M.,

Gorostiza, J.F., Pacheco, R., Rivas, R., Corrales, A.,

Delgado, E., García, D., 2006. Maggie: A robotic

platform for human-robot social interaction. IEEE

International Conference on Robotics, Automation

and Mechatronics (RAM 2006). Bangkok. Thailand.

Sambataro, F., Dimalta, S., Di Giorgio, A., Taurisano, P.,

Blasi, G., Scarabino, T., Giannatempo, G., Nardini,

M., Bertolino, A., 2006. Preferential responses in

amygdala and insula during presentation of facial

contempt and disgust. European Journal of

Neuroscience, 24, 2355-2362.

Trivers, R. L., 1971. The evolution of reciprocal altruism.

Quarterly Review of Biology, 46, 35-57.

Windhager1, S., Slice, D.E., Schaefer, K. Oberzaucher, E.

Thorstensen, T. Grammer, K., 2008. Face to face. The

perception of automotive designs. Human Nature.

D.O.I.: 10.1007/s12110-008-9047-z

ICEIS 2009 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

270