MOBILE TOURISM SERVICES

Experiences from Three Services on Trial

Niklas Eriksson and Peter Strandvik

Institute for Advanced Management Systems Research, ÅboAkademi University, Jouhkahainenkatu 3-5A, Turku, Finland

Keywords: Mobile tourism services, technology adoption.

Abstract: For this study a field trial was conducted to identify the determinants for tourists’ intentions to use three trial

services targeting tourists on tour, in this case on the Åland Islands in Finland. We identified that the major

barrier for the non usage of the trial services was linked to the type of travel that the trial group participated

in. Also price transparency and ease of use especially ease to take new mobile services into use should be

highlighted in mobile tourism service development. Moreover, we came across some basic reminders to

take into account when commercializing mobile services, such as carefully define a customer target group,

estimate potential usage volume and plan marketing / sales tactics. These aspects are not necessarily

realized enough in technology development.

1 INTRODUCTION

The use of the Internet for doing commerce or

interacting with customers has been growing rapidly

in the world wide tourism industry. Mobile

commerce, or e-commerce over mobile devices, on

the other hand has had many conflicting predictions

on its future popularity. Most predictions have been

overly optimistic. However, the benefits that arise

from mobile technology have not yet been fully

delivered, which to some extent is explained by the

fact that mobile applications, due to complexity or

lack of relevance, fail to meet customers’

expectations (Carlsson et al. 2006). Travel and

tourism is an industry in which several different

projects have been conducted where mobile

applications have been developed, tested and

implemented, some even with moderate success (e.g.

Ardissono et al 2003, Kramer et al 2005, Schmidt-

Belz et al 2003, Repo et al 2006). Some of these

pilot projects (e.g. Kramer et al 2005, Schmidt-Belz

et al 2003) have been focusing on GPS which the

average tourist doesn’t yet have in his/her handheld

mobile device. Therefore it seems relevant to build

and test services that actually can be used by the

average tourists. Nevertheless previous pilots have

given us valuable information on the potential of

mobile technology.

The New Interactive Media (NIM) project, with

funding from the European Union and the regional

government of the Åland islands, is a development

programme of increasing knowledge, production and

use of new interactive media on the Åland Islands

1

in Finland. Within the project several mobile

applications have been developed for the travel and

tourism sector on the islands. Three of these services

will be presented more in detail in this paper:

MobiPortal, TraveLog and MobiTour. A field trial

of these services with real incoming tourists to the

Åland Islands using their own mobile phones has

also been conducted. Findings and experiences from

this trial will be reported. Possible determinants for

consumers’ intentions to use mobile tourism services

will be discussed as well.

2 SERVICE DESCRIPTIONS

The services have been planned with a common

logic namely the Braudel rule: freedom becomes

value by expanding the limits of the possible in the

structures of everyday life (as presented by Keen &

Mackintosh 2001). The rule is then translated into a

tourism setting which means that tourists’ real or

perceived need has to be met by the services and

1

Åland is an autonomous and unilingual Swedish region in

Finland with its own flag and approximately 26.700 inhabitants.

Åland is situated between Finland and Sweden and consists of 6

500 islands. (www.visitaland.com)

115

Eriksson N. and Strandvik P. (2008).

MOBILE TOURISM SERVICES - Experiences from Three Services on Trial.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business, pages 115-123

DOI: 10.5220/0001904001150123

Copyright

c

SciTePress

moreover, the services need to profoundly change

the way a tourist does or experience something – and

to the better (Harkke 2007).

MobiPortal

is a mobile version of an information

portal www.visitaland.com which is the official

tourist site of the Åland Islands. The portal includes

search for events, restaurants etc., a map service and

facts on the Åland Islands.

TraveLog

is a mobile community for incoming

tourists to share experiences from the Åland Islands

with each other. The virtual meeting place includes

stories, pictures, tips and interactions.

MobiTour

is a guide for attractions such as the

Bomarsund fortress which is downloadable /

streamable to the visitors’ own devices. The guide

includes voice and/or video guidance.

All these three services ought to expand the

limits of a tourist to the Åland Islands according to

the Braudel rule by enabling 1) instant access to

local information, 2) enhanced communications with

other people with the same interests and 3)

experience enhancement for certain unmanned

attractions. Especially experience enhancement

features are generally seen as key drivers for

successful customer satisfaction in tourism (Pine &

Gilmore 1999). The determinants for consumer

usage of mobile tourism services are, however, a

complex issue which will be discussed next.

3 POSSIBLE DETERMINANTS

Several models of technology adoption have been

developed. One of the most used models is the

technology acceptance model (TAM) by Davis

(1989) which is based on the theory of reason action

(TRA) by Fishbein et al. (1975). Other often used

models in technology adoption research are the

diffusion of innovations theories (DIT) by Rogers

(1995) and the unified theory for the acceptance and

use of technology (UTAUT) by Venkatech et al.

(2003) which combines TAM with other acceptance

model e.g. DIT. Here different components of these

models will be discussed, together with relevant

research theories for adoption of electronic and

mobile services, to identify possible determinants for

consumer intentions to use mobile tourism services.

The TAM model proposes two determinants,

perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use,

which impact the acceptance of technology and

adoption behavior as a result (Davis 1989).

Perceived usefulness is defined as “the degree to

which a person believes that using a particular

system would enhance his or her performance”.

Perceived ease of use is defined as “the degree to

which a person believes that using a particular

system would be free of effort”. The two TAM

determinants are proposed to identify the intended

usage behavior of a system and are widely used as a

backbone for research in adoption of technology.

However, the first TAM variable perceived

usefulness is foremost designed to research work

performance improvements in organizational

contexts. In consumer markets consumer behavior is

also influenced by other factors. It is typical that

non-efficiency factors impact consumer adoption of

technology, e.g. good tourist technologies are not

only those that make tourists more efficient, but that

also make tourism more enjoyable. Thus tourism can

be characterized as wandering, where tourists

attempt to enjoy the city environment and chance

upon things of interest, rather than optimizing

(Brown & Chalmers 2003). As the mobility (on the

move) capability is generally seen as the key value

driver in m-commerce (Anckar & Eriksson 2003),

mobile technology clearly has the potential to

support the wandering aspect of tourism. A word

like flexibility has commonly been used to describe

the independence of time and space that is provided

by mobile technology. According to Kim et al.

(2005) the hedonic motivation or the enjoyment

aspect of tourism has, however, not been clearly

defined in mobile technology acceptance models.

The perceived type and degree of perceived value of

a mobile service depend on the other hand on the

situation or context of usage (Mallat et al 2006, Lee

& Jun, 2005). Anckar & Dincau (2002) introduced

an analytical framework that identifies the potential

value creating features of mobile commerce. Mobile

value elements in the framework for consumers on

the move are: Time-critical arrangements,

Spontaneous needs, Entertainment needs, Efficiency

ambitions and Mobile situations. Time-critical

arrangements refer to applications for situations

where immediacy is desirable (arise from external

events), e.g. receive alerts of a changed transport

schedule while on tour. Spontaneous needs are

internally awakened and not a result of external

events, e.g. find a suitable restaurant while

wandering around. Entertainment needs, killing

time/having fun, especially in situations when not

being able to access wired entertainment appliances,

e.g. kill or fill time in transportation. Efficiency

ambitions aim at productivity, e.g. use dead spots

during a travel to optimize time usage. Mobile

situations refer to applications that in essence are of

value only through a mobile medium (e.g.

localization services), which ought to be the core of

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

116

mobile commerce. Consequently perceived mobile

value represent the degree to which a person

perceives value arising from the mobility of the

mobile medium.

Nevertheless not only the medium creates value

for the consumer but the essence of the services as

well. We refer to such value as perceived service

value. For example for a tourist in a planning or

booking situation the key to successful satisfaction

would be timely and accurate information relevant to

the consumer’s needs (Buhalis 2003). Equally

important for a tourist visiting a historical attraction

may be the satisfaction of educational and

entertainment (edutainment) needs (HyunJeong &

Schlisser 2007). Similarly a person with a mission to

share experiences with others may find satisfaction

when a community responds (Arguello et al 2006).

The three examples refer to the essence of the three

services on trial.

The second TAM determinant perceived ease of

use has been widely discussed in mobile commerce.

Limitations of mobile devices (e.g. screen size)

cause consumers to hesitate whether to adopt mobile

commerce or not. According to Cho et al (2007)

device limitations suggest that focusing on easy to

use mobile applications could enhance the consumer

acceptance of mobile commerce. Kaasinen (2005)

points out that mobile services need to be easy to

take into use as well as mobile services are typically

used occasionally and some services may be

available only locally in certain usage environments.

As a consequence, information on available services

should be easy to get and the services should be easy

to install and to start using. The ease of taking a

service into use may in fact have a direct impact on

the adoption behaviour of a mobile service

(Kaasinen 2005). On the other hand when problems

arise, users in the consumer market are often

expected to solve the problems on their own (Repo

et. al 2006). Consequently the use may rely on

proper instructions or on a helping hand from

someone. Proper support conditions also in a

consumer market may therefore be important

especially for advanced mobile services.

Nevertheless consumers many times expect to take a

new product or service into use without instructions

or help.

According to Rogers (1995),”The innovation-

decision is made through a cost benefit analysis

where the major obstacle is uncertainty”. Perceived

risk is commonly thought of as felt uncertainty

regarding possible negative consequences of using a

product or service and has been added to the two

TAM determinants as a negative influencer on

intended adoption behaviour (Featherman & Pavlou

2003). Trust, as trust in the service vendor to

minimize the risks, has also been added to the TAM

model (e.g. Cho et al 2007, Kaasinen 2005) and

pointed out as a strong influencer on the intended

use of mobile services due to that mobile commerce

is still at its initial stage (Cho et al. 2007). We refer

to trust as the perceived risk defined by Featherman

& Pavlou 2003. They divide the perceived risk for

electronic services into the following elements;

performance risk, financial risk, time risk,

psychological risk, social risk and privacy risk.

Performance risk refers to the possibility of a service

to malfunction and not performing as it was

designed and advertised. The financial risk refers to

the potential monetary outlay associated with the

initial purchase price as well as the subsequent

maintenance cost of the product and the possibility

of fraud. Time risk refers to that the consumer may

lose time when making a bad purchasing decision

e.g. by learning how to use a product or service only

to have to replace it if it does not perform to

expectations. Psychological risk refers to the

potential loss of self-esteem (ego loss) from the

frustration of not achieving a buying goal. Social

risk refers to potential loss of status in one’s social

group as a result of adopting a product or service,

looking foolish or untrendy. Privacy risk refers to

the potential loss of control over personal

information, such as when information about you is

used without your knowledge or permission. At least

security and privacy issues have been highlighted as

barriers to mobile commerce (O’Donnell et al.

2007). Also financial risks in form of high costs,

including operating costs and initial costs, have been

highly ranked by consumers as hindrances for m-

commerce in its early stages (Anckar et al. 2003).

In UTAUT social influence among other

constructs is added to the two TAM components and

defined as the degree to which an individual

perceives that important others believe he should use

the new system (Venkatech et al., 2003). Social

influence is also known as subjective norm in the

theory of reason action (Fishbein et al 1975) and in

its extension theory of planned behavior (Arjzen

1991). In consumer markets image and social status

have been proposed to impact consumers’ adoption

of mobile services (Teo & Pok 2003). Also the

number of users may influence, especially for

community services which usefulness heavily

depend on activity of different participants

(Pedersen et al 2006). Furthermore other external

sources such as media reports and expert opinions

MOBILE TOURISM SERVICES - Experiences from Three Services on Trial

117

may influence consumers’ perception of electronic

services (Bhattacherjee 2000).

Demographic variables such as gender and age

are commonly used in consumer research. For

example gender and age might through other

constructs influence the intended adoption behavior

of mobile services (Nysveed et al. 2005). According

to the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991)

control beliefs constitute individuals’ belief that they

have the necessary resources and knowledge to use

an innovation. For example skills or earlier

experience of using mobile services may influence

the adoption intentions of new mobile services.

When discussing consumer behavior in tourism and

the impact of information and communication

technologies (ICTs) a clear distinction should also

be made between experienced and inexperienced

travelers (travel experience). The first group mainly

feels more comfortable organizing their holidays and

thereby taking advantage of ICT tools available to

them more easily (Buhalis 2003). Moreover

inexperienced destination travelers usually need a lot

more local information. Innovations also need to

comply with the existing values and needs of the

individual in an everyday life setting (Moore &

Benbasat 1991), in this case while on tour. For

example the values of the individual may differ

depending on the type of travel they are on: leisure

or business, where the former ought to call for

services with enjoyability rather than efficiency. In

consumer markets mobile services also compete

against existing and constantly developed

alternatives. Thus consumer habits are usually quite

slow to change from known alternatives (Dahlberg

& Öörni 2007). People are on average risk-averse.

But that is not true for everyone as we have

individuals who are earlier to adopt new ideas than

others (Rogers 1995). Such personal characteristics

make diffusion of innovations possible. Personal

innovativeness is the willingness of an individual to

try out and embrace new technology based services.

Individuals’ limited mobile device readiness has as

well been seen as a great negative influencer of the

usage of more advanced mobile services (Carlsson et

al. 2004). We refer demographic variables,

experience of mobile services, travel experience,

destination experience, type of travel, personal

innovativeness and user device readiness as

discussed here to tourist characteristics as they

illustrate key characteristics of an individual that

may influence the intended use of mobile tourism

services.

Based on the literature discussion possible

determinants for consumer intentions to use mobile

tourism services are: perceived mobile value and

service value, perceived ease of use, social

influence, perceived risk and tourist characteristics.

Mobile value and service value replace perceived

usefulness as presented in the TAM model. Ease of

use is defined as in the TAM model where also ease

of taking a service into use is included. Social value

is defined as in UTAUT and perceived risk as

presented by Featherman & Pavlou (2003). Tourist

characteristics constitute key characteristics of an

individual on-tour. The defined determinants are

summarized in table 1.

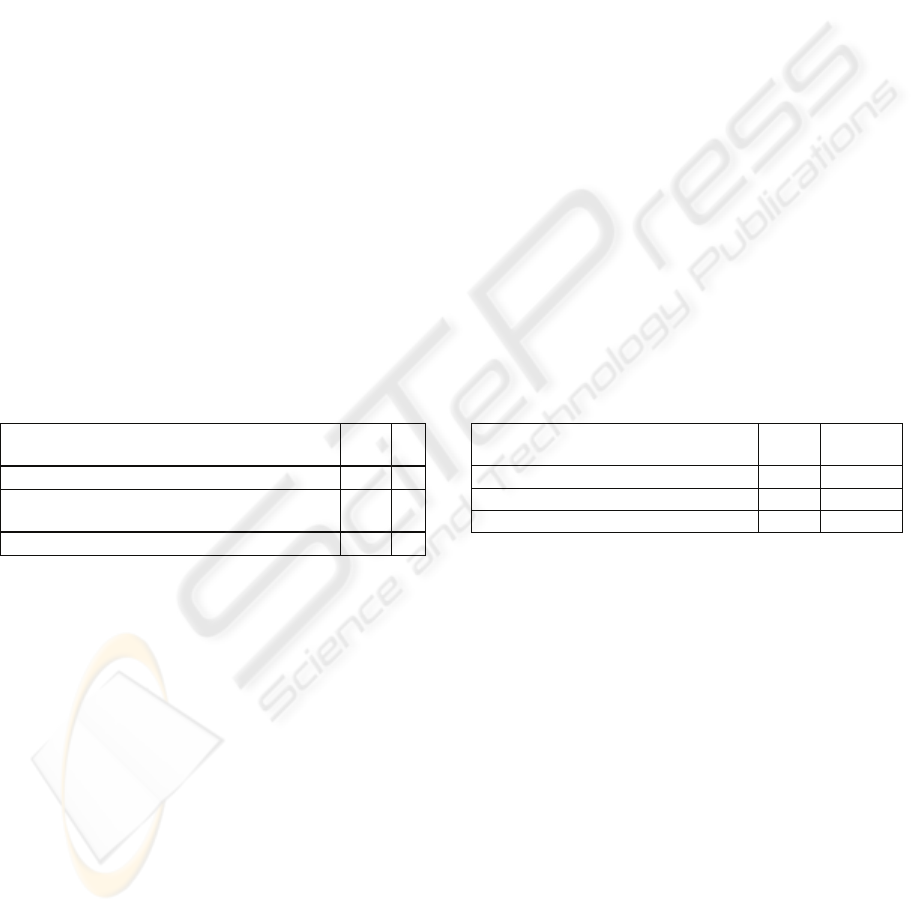

Table 1: Possible determinants for consumer intentions to

use mobile tourism services.

Mobile value: the degree to which a person perceives

value arising from the mobility of the mobile medium

Service value: the degree to which a person perceives

value arising from the essence of the service.

Ease of use: the degree to which a person believes that

using a particular service would be free of effort

Risk: the degree to which a person feels uncertainty

regarding possible negative consequences of using a

service.

Social influence: the degree to which an individual

perceives that important others believe he should use

the service

Tourist characteristics: Demographics, Experience of

mobile services, Travel experience, Destination

experience, Type of travel, Personal Innovativeness,

Device readiness

4 THE FIELD TRIAL SETUP

According to Repo et al. (2006) TAM theories and

similar approaches have little relevance in the real

product development process. Product developers

need first hand user feedback in form of personal

interaction rather than by reading research reports.

The arguments are based on experiences from

piloting a mobile blog service for tourists, where the

user gave direct feedback to the developers orally

and through survey forms. Involving the consumer

in the development process of products or services

can be very rewarding indeed (von Hippel 2005).

With the theoretical foundation (Table 1) in mind

and with the idea of directly interacting with the

consumers to receive direct and spontaneous

feedback to the product developers we designed a

field trial which included oral, observed and survey

data collection.

The trial was conducted during a conference in

the capital of the Åland Islands Mariehamn 21 –

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

118

22.9.2007 at the legislative assembly where the main

activities of the conference were held. The

conference was arranged by the local Junior

Chamber of Commerce organization and it was

called WestCongress2007. Members of similar

organizations in the western regions of Finland were

invited to attend the conference. A total of 191

participants had registered in advance for the

conference. The trial was coordinated in cooperation

with the conference director who offered assistance

with e.g. stand preparations and informing the

participants in advance of the mobile services in

conference guides, online and during registration.

Our stand was set up at the main entrance of the

building where the main activities were held. The

main entrance was the place that we anticipated

would be the busiest during the first parts of the

conference when we were invited to promote and

demonstrate our services. The stand was equipped

with a video projector showing animated picks of

the services and also flyers, tables and chairs for

comfortable discussions with the conference

attendants.

At our stand the conference participants were

informed more in detail of the services. The services

were also demonstrated, which gave us a chance to

observe peoples first time reactions. The stand also

provided for us a good place to freely discuss

different issues regarding the services with the

participants. Participants filled out voluntarily a

questionnaire which also was an agreement to

contact them by e-mail after the conference to

follow up on their own independent use of the

mobile services during their stay on the Åland

Islands. Each phone and operator connection (device

readiness) was checked by the stand representatives

to ensure that the participants actually were able to

use their own phones for the services.

In the questionnaire the participants were asked

to fill out questions according to the constructs

defined for tourist characteristics:

Demographics: Gender and age

Experiences of mobile services: Commonly

used services were listed with the alternatives:

[1] continuously using [2] have tried [3] have

never tried.

Travel experience: How often they travel for

more than one day: [1] several times a month

[2] ~ once a month [3] 3 – 9 times a year [4] <

three times a year.

Destination experience: If they have visited the

Åland Islands before: [1] Yes, > 5 times [2]

Yes, 2 – 5 times [3] Yes, once [4] Never and

their knowledge of the Åland Islands [1]

Excellent [2] Good [3] Satisfactory [4] Not at

all.

Type of travel: if they consider

WestCongress2007 to be: [1] a leisure trip [2] a

business trip.

Personal Innovativeness: Three statements were

proposed on a five point scale: [5] definitely

agree - [1] definitely disagree: I want to get

local information through my mobile phone

when… 1. I plan my program e.g. in the hotel 2.

I’m on my way to a local place with e.g. bus 3. I

get acquainted with a local place on foot. The

statements were developed based on the kind of

mobility situations tourists may experience.

Kristoffersen & Ljungberg (2000) distinguish

between three types of mobility: visiting,

traveling and wandering. Visiting, an actor

performs activities at different locations (e.g. a

hotel). Traveling, an actor performs activities

while moving between different locations

usually inside a vehicle (e.g. bus). Wandering,

an actor performs activities while moving

between different locations where the locations

are locally defined within a building or local

area (e.g. on foot).

For the follow up a semi-open web questionnaire

was used to receive feedback on the participant’s

actual use of the three services. The web

questionnaire was sent to the participants by e-mail

two days after the conference finished ensuring that

their service experience would be fresh in their

minds. A reminder was sent a week later. The

participants were asked to state for each of the three

services whether they had used it or not. Their

answer was followed up with an open question on

their primary motivation for using or not using the

service. In the analysis the answers were interpreted

according to the theoretical foundation on

determinants for the intended use of mobile tourism

services. Additionally the participants were asked to

state what kinds of problems they had run into if

problems occurred. The participants were also to

state on a five point likert scale ([5] Yes, definitely -

[1] Definitely not) for each service what their

intentions are to use similar services in the future

while visiting a destination. Finally the participants

were free to comment on the service.

5 THE PARTICIPANTS

Members signed up in advance for the conference

were 191 in total. However, about thirty persons

MOBILE TOURISM SERVICES - Experiences from Three Services on Trial

119

didn’t register. We estimated that about 50 persons

visited our stand. Out of these 50 persons voluntarily

and without a prize draw 23 filled out the

questionnaire and allowed us to contact them after

the conference for the follow up. 20 out of 23

persons had a mobile phone and an operator

connection (device readiness) that allowed them to

use the services. Thereby it was relevant to send the

follow up by e-mail to these 20 persons. Two mail

addresses did not respond. Out of the 18 persons that

the follow up went to 9 answered it.

Of the 23 that filled out the questionnaire 12

were men and 11 women. The average age was 35.

The majority (66%) stated that they travel about

once a month for more than one day. Most of them

(66%) had visited the Åland Islands before at least

two times or more. However, a majority (66%)

answered that they know the Åland Islands

satisfactory or not at all. Almost all (96%) felt the

WestCongress2007 to be a leisure trip. Of the 23

participants all had at least at some point tried to use

a mobile service and a clear majority (66%) used at

least one mobile service continuously. A total of

74% (17) of the participants answered that they want

to get local information with their mobile phone for

at least one of the statements in table 2.

Table 2: Local information with mobile phone.

I want to get local information through my

mobile phone when...

N

Tot 23

%*

I plan my program e.g. in the hotel 10 43

I’m on my way to a local place with e.g. bus,

car

14 61

I get acquainted with a local place on foot 11 48

* 5 = definitely agree and 4 = partly agree

6 EXPERIENCES FROM THE

TRIAL

To draw peoples’ attention to our stand we really

needed to sell the services. As people were moving

for different things in the building and to other

locations in the surrounding area a major job was to

get them to stop by the stand. Very few participants

stopped without a few sales lines from the stand

representatives, although they were informed in

advance of the services and the stand was

strategically placed at the main entrance.

Most people who visited the stand expressed a

positive response by the first sight of the services.

Comments like “that seems practical” and “I already

use mobile news services so why not use these

services” were given. Especially MobiPortal

awakened concrete interest as it was bookmarked by

a couple of stand visitors. A few persons also

praised the visual design of the MobiTour guide.

However, some people were spontaneously skeptic

about the long download times for MobiTour. Nor

did anyone ask for transactions over Bluetooth

although it would have been possible at the stand.

Several persons instantly also asked for the price of

the services. The services were not charged for and

it seemed like the transaction costs were obvious to

most visitors and not a hindrance to use, except for

the large files of MobiTour. Connection problems

occurred with at least one network operator which

interestingly led to that a few thought there was

something wrong with the trial services.

None of the nine respondents to the follow up

had on their own used any of the trial services. All

reported that their primary motivation for the no use

was that they didn’t experience a need to use the

services during their stay at the conference on the

Åland Islands.

The future intended use of similar services as the

ones on trial were reported as shown in table 3.

Services similar as MobiPortal received the highest

score.

Table 3: Intended use of similar services.

When visiting a destination in the

future I intend to use …

N Mean*

Similar services as MobiPortal 9 3,33

Similar services as TraveLog 9 2,89

Similar services as MobiTour 9 2,89

*[5] Yes, definitely – [1] Definitely not

7 DISCUSSION

A customer target group needs to be defined for each

mobile service developed (Hoegg & Stanoevska-

Slabeva 2005). The primary target group for the

three mobile services on trial is visitors to the Åland

Islands. The trial targeted participants of

WestCongress2007 who visited the Åland Islands.

When analyzing the trial group it can be said that it

was both right and wrong. It ought to be the right

group based on the fact that most participants who

filled out the questionnaire had a device readiness

(87%) that allowed the services to be used on their

own phone. The group already continuously used

mobile services to a great extent (66%) and thereby

the barrier to take on new services ought to be lower.

Their knowledge of the Åland islands was only

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

120

satisfactory or none (66%) which ought to create a

need for local information. Also their willingness to

get local information in different situations (74%)

with their mobile phone was positive. Moreover the

group was an experienced group of tourists (66%)

which generally is found to be positive regarding

usage of information and communication

technology. On the other hand the group had a ready

made program during the weekend and we observed

that they also asked their hosts for tips and

directions. The need for local information and

guidance may therefore have been satisfied.

Moreover they had their conference group who they

met with continuously to share their experiences

with. Consequently the service value of the three

services on trial was already met by other means of

interaction.

The analyses of the trial group indicate that the

same people but with another mission to visit the

Åland Islands could be a potential user group of the

services on trial. The mobile value of using mobile

services is, as discussed in the theoretical

foundation, very much situation based. Moreover,

the proposed value needs to comply with the user’s

existing on-tour values. In this case self arrangement

values by using a mobile phone necessarily didn’t

exist due to the packaged set up of the conference.

Consequently the type of travel, as packaged or non-

packaged, is therefore to be taken into account as an

influencer of the intended use of mobile tourism

services. A non-packaged tour ought to comply

better with an individual’s values of self

arrangement / service. Nevertheless customized

mobile services aimed at specific needs of packaged

groups such as conference attendants may indeed

generate value.

The trial also shows that we cannot forget that

new technology innovations very seldom sell

themselves. Much of our efforts at our stand were

sales related. Launching new mobile services

certainly need to be pushed by creating awareness

among the potential consumers as for any other new

product. Similar pointers have been presented by

Collan et al. (2006): “Hot technology doesn’t sell

itself, it has to be marketed to the consumer in the

shape of value adding services that are easy to use”.

Therefore marketing / sales tactics influence needs

to be set as a determinant for consumer intentions to

use mobile tourism services.

Questions on the prices of the trial services were

the most frequent ones asked during the trial.

Therefore it seems that the financial risk is carefully

accounted for by the consumers in their intentions to

use a mobile tourism service. In this trial the

services were free of charge and the transaction

costs didn’t seem to be a barrier. Nevertheless our

experience from this trial is that the service price and

potential transaction costs must be transparent to the

consumers to minimize uncertainty of the monetary

layout. The monetary aspect may be even more

important for foreign visitors as transaction cost may

rise noticeably.

Even though many participants expressed a

general interest in the services it is also a fact that no

one reported that they actually used the services on

trial. Thereby questions are raised from a business

point of view on the potential usage volumes of the

services on trial at this time and place. We certainly

need to be very realistic when we launch mobile

services on the potential volume of usage, especially

when setting the business logic (Collan et al. 2006).

Moreover product developers need to remember to

look at things from a consumer perspective. For

example in this trial the consumers thought the trial

services didn’t work because of an operator

problem. In the eyes of the consumer this means a

malfunctioning product which is useless. Similarly

long download times to access a service for a

temporary use may cause the consumer to view the

service as too time consuming to take into use.

Neither can we expect consumers to install services

in advance as according to Kaasinen (2005), “users

are not willing to spend their time on something that

they do not get immediate benefit from.”

Consequently the ease of use aspect must be

highlighted by product developers as mobile tourism

services may be only temporarily used during a visit

to a destination or a local place.

8 CONCLUSIONS

This paper presented possible determinants for

consumer intentions to use mobile tourism services.

A major driver according to the six identified

determinants; mobile value, service value, ease of

use, risk and social influence and tourist

characteristics couldn’t be determined as no one

used the trial services on their own. The major

barrier for the non usage of the three services among

the trial group seemed to be linked to the value

aspect of the packaged tour (type of travel). Based

on the experience from this trial we propose that

researchers and practitioners especially take the

following into account:

The type of travel is a key aspect in designing

mobile tourism services

MOBILE TOURISM SERVICES - Experiences from Three Services on Trial

121

Marketing / sales tactics influence should be

highlighted as a determinant for consumer

intentions to use mobile tourism services

Price transparency is an important aspect to

minimize consumers’ perceived risk of mobile

tourism services

Ease of use aspects should be highlighted even

more for mobile tourism services as they may

be only temporarily used

These pointers can also be seen as reminders in

technology development where basic

commercialization routines sometimes aren’t

realized enough. As for any other product defining a

customer target group, estimate potential usage

volumes and plan marketing are vital steps in

launching mobile tourism services.

It needs; however, to be kept in mind that the

experience is based on only one field trial and

therefore further research in evaluating mobile

tourism services and similar mobile services is

needed. The recruitment of trial users could as well

be done differently. According to Kaasinen (2005)

ideally users should be allowed to use the trial

services freely but it may lead to, as in this trial, to a

no usage. Therefore some rules on minimum trial

times should be set up, where additional usage to the

minimum can be considered as real usage. Logs can

also be helpful in data collection to receive prompt

service usage data in addition to follow up data from

the respondent. Moreover, phone interviews may

give more extensive answers and better response

rates in a follow up data collection of the same

character as in this trial.

REFERENCES

Anckar, B., D’Incau, D., 2002. Value creation in mobile

commerce: Findings from a consumer survey. Journal

of Information Technology Theory and Application,

vol. 4, pp. 43-65.

Anckar, B., Eriksson, N. 2003. Mobility: The Basis for

Value Creation in Mobile Commerce? Proceedings of

the International Conference SSGRR’03. Telecom

Italia learning Services L’Aquila, Italy

Anckar, B., Carlsson C., Walden, P., 2003. Factors

affecting consumer adoption decisions and intents in

mobile commerce:empirical insights. Proceedings in

the 16

th

Bled eCommerce conference

Ajzen, I., 1991. The Theory of Planned Behavior,

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, vol. 50, pp. 179-211.

Ardissono, L. et al. 2003. INTRIGUE: Personalized

recommendation of tourist attractions for desktop and

handset devices. Applied Artificial Intelligence:

Special Issue on Artificial Intelligence for Cultural

Heritage and Digital Libraries, vol. 17, no. 8-9, pp.

687-714.

Arguello, J., Butler, B., Joyce, E., Kraut, R., Ling, K.,

Rosé, C., Wang, X., 2006: Talk to me: foundations for

successful individual-group interactions online

communities, Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference

on Human Factors in computing systems, Montréal

Canada

Bhattacherjee, I., 2000. Acceptance of e-commerce

services: the case of electronic brokerages. IEEE

Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics – Part

A: Systems and Humans, vol 30, no 4, pp. 411 - 420.

Buhalis, D., 2003. eTourism: information technology for

strategic tourism management, Prentice Hall, Harlow.

Brown, B., Chalmers, M., 2003. Tourism and mobile

technology. Proceedings of the Eight European

Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative

Work (Kuutti, K. and Karsten, E. H. Eds.), Helsinki,

Finland, 14-18 Sep. 2003, Kluwer Academic Press.

Carlsson C., Carlsson J., Puhakainen J., Walden P. 2006.

Nice mobile services do not fly. Observations of

mobile services and the Finnish consumers.

Proceedings in the 19

th

Bled eCommerce conference.

Carlsson, C. Hyvönen, K., Repo, P., Waldén, P., 2004. It’s

All About My Phone! Use Of Mobile Services In Two

Finnish Consumer Samples. Proceedings in the 17

th

Bled eCommerce conference 2004.

Cho, D., Kwon, H., Lee, H-Y, 2007. Analysis of trust in

Internet and mobile commerce adoption. Proceedings

of the 40

th

Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences (HICCS)

Collan, M., Sell, A., Anckar, B., Harkke V. 2006. Using

E- and M-Business components in Business:

Approaches, Cases, and Rules of Thumb. Chapter IX

in Entrepreneurship and Innovations in E-Business:

An Interactive Perspective. Fang Zhao. Idea group.

Dahlberg, T., Öörni, A. 2007. Understanding changes in

consumer payment habits – Do mobile payments and

electronic invoices attract consumers? Proceedings of

the 40

th

Hawaii International Conference on System

Science (HICSS) 2007.

Davis, F. D., 1989. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease

of Use and User Acceptance of Information

Technology, MIS Quarterly, vol 13, no 3, pp. 319-340.

Featherman, M., Pavlou, P. 2003. .Predicting e-services

adoption: a perceived risk facets perspective. Journal

of Human Computer studies, no. 59, pp. 451–474.

Fishbein, M., Ajzen, I., 1975. Belief, attitude, intention

and behavior: an introduction to theory and research.

Reading, MA Addison-Wesley

Harkke, V., 2007. NIM Åland: the quest for useful mobile

services. Proceedings of 20

th

Bled eConference.

Hoegg, R., Stanoevska-Slabeva, K., 2005. Towards

Guidelines for the Design of Mobile Services. 13th

European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS)

HyunJeong, K., Schliesser, J., 2007. Adaptation of

Storytelling to Mobile Information Service for a Site-

Specific Cultural and Historical Tour. Journal of

ICE-B 2008 - International Conference on e-Business

122

Information Technology & Tourism. vol. 9, no. 3-4

Cognizant, USA.

Kaasinen, E., 2005. User acceptance of mobile services –

value, ease of use, trust and ease of adoption. Doctoral

Dissertation 566, VTT, Espoo, Finland

Keen, P., Macintosh, R., 2001. The Freedom Economy –

Gaining the M-commerce Edge in the Era of the

Wireless Internet. McGraw-Hill, Berkeley.

Kim, D., Park, J., Morrison, A., 2005. A model of Tourist

acceptance for mobile technology. Submitted to the

11

th

annual conference of Asia Pacific Tourism Assoc.

Kramer, R., Modsching, M., ten Hagen, K., 2005. A

Location Aware Mobile Tourist Guide Selecting and

Interpreting Sights and Services by Context Matching.

Proceedings of the Second Annual International

Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Systems:

Networking and Services.

Kristoffersen, S., Ljungberg, F., 2000. Mobility: From

Stationary to Mobile Work, Planet Internet, Chapter 6,

K. Braa, C. Sorensen, B. Dahlbom (eds).

Studentlitteratur, Lund, Sweden.

Lee, T., Jun, J., 2005. Contextual perceived usefulness?

Toward an understanding of mobile commerce

acceptance. Proceedings of the International

Conference on Mobile Business (ICMB).

Mallat, N., Rossi, M., Tuunainen, V., Öörni, A., 2006. The

impact of use situation and mobility on the acceptance

of mobile ticketing services. Proceedings of the 39

th

Hawaii International Conference on System Science

(HICSS) 2006.

Moore, G., Benbasat, I, 1991. Development of an

Instrument to Measure the Perceptions of Adopting an

Information Technology Innovation. Information

Systems Research, vol 2, no 3, pp. 192-222.

Nysveen, H., Pedersen, P.E., Thorbjørnsen, H. 2005.

Explaining intention to use mobile chat services:

moderating effects of gender, Journal of Consumer

Marketing, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 247 - 256

O'Donnell, J., Jackson, M., Shelly, M., Ligertwood, J.,

2007. Australian Case Studies in Mobile Commerce.

Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic

Commerce Research vol. 2, no. 2, August 2007 pp. 1 –

18.

Pedersen, P E., Munkvold, B E., Akselsen, S., Ytterstad,

P. 2006. The Business Model Concept - Relevance for

Mobile Tourism Services Innovation and Provision.

Fornebu, Telenor Research & Innovation. Report R&I

R 09/2006.

Pine, J., Gilmore J., 1999. The Experience Economy. Pine

and Gilmore Press.

Repo, P., Hyvönen, K., Saastamoinen, M., 2006.

Traveling from B2B to B2C: Piloting a Moblog

Service for Tourists. Proceedings of the International

Conference on Mobile Business (ICMB) 2006.

Rogers, E., M., 1995. Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press,

New York. 4th edition.

Schmidt-Belz, B., Zipf, A., Poslad, S. & Laamanen, H.,

2003. Location-based mobiletourist services – first

user experiences, in Information and Communication

Technologies in Tourism 2003, Frew, A. J., Hitz, M. &

O’Connor, P.(Editors.) Springer, Wien

Teo, TSH, Pok, SH., 2003. Adoption of WAP-Enabled

Mobile Phones among Internet Users. Omega, vol 31

pp. 483–498

Tussyadiah, I., Fesenmaier, D., 2007. Interpreting tourist

experiences from firstperson stories: a foundation for

mobile guides. 15th European Conference on

Information Systems (ECIS) 2007.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., Davis, F. D.,

2003. User acceptance of information technology:

toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, vol. 27, no. 3,

pp. 425-478.

Von Hippel, E., 2005. Demoratizing Innovation, The MIT

Press, London England

MOBILE TOURISM SERVICES - Experiences from Three Services on Trial

123