CULTURAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN TAIWANESE AND

GERMAN WEB USER

Challenges for Intercultural User Testing

Anna Karen Schmitz, Thomas Mandl and Christa Womser-Hacker

Information Science

University of Hildesheim, Germany

Keywords: Intercultural Usability, Web Design.

Abstract: Measuring the performance of a user with a web site reveals that the culture of a user is an important factor.

A test of Taiwanese and German students resulted in various significant differences in effectiveness,

efficiency and satisfaction. Task design and results of the experiment are presented. Human-computer

interaction can be evaluated by different means. The paper discusses how methods need to be interpreted in

international user test settings. For example, time might not be a valid measure in long-term oriented

cultures for all interaction tasks.

1 INTRODUCTION

Culture determines the way people deal with their

environment and how they interact in social groups.

The role of superiors in a society and the perception

of time are examples for issues which are dealt with

differently in different nations. Culture affects the

design of information systems as well. Optimal

design of information systems for users from other

cultures requires an understanding of the concept of

culture and the factors that contribute to its

existence. In a globalized world, such an analysis

can ultimately lead to better information systems. A

good understanding of the cultural differences

between web pages and their perception can support

system designers in optimally modifying their pages

for a particular culture.

Finding out differences about web site

perception is important and at the same time

difficult. User testing in human-computer interaction

usually randomly selects users and assigns them to

(often two) different system designs in order to

determine the superior design. Doing this,

comparable user populations can be created.

However, culture is a variable which cannot be

randomly assigned to the users. Therefore, culture

might have effects on the test situation which cannot

be controlled. Such test are sometimes called quasi-

experimental (Borth & Döring, 1995). The

interpretation of intercultural user tests needs to take

care of these issues. Some of these issues are

discussed in this paper. They are as far-reaching as

measures of success are concerned.

The remainder of this paper is organized as

follows. Section two defines culture for the purpose

of this paper. The next section briefly reports the

state of the art on cultural research within web

design. Section four explains the experimental setup.

Section four five elaborates the results which are

followed by a discussion and the paper ends with a

conclusion.

2 CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

BETWEEN TAIWAN AND

GERMANY

There are many definitions of culture (Kroeber &

Kluckhofen, 1952). The influential Dutch

anthropologist Hofstede defined culture as learned

patterns of ”thinking, feeling, and potential acting”

that form the mental program or the ”software of the

mind” (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005) of an individual.

This particular ”software” affects our way of

thinking and acting in the world. National or social

cultures define how people interact with each other,

e.g. in groups and their environment.

62

Karen Schmitz A., Mandl T. and Womser-Hacker C. (2008).

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN TAIWANESE AND GERMAN WEB USER - Challenges for Intercultural User Testing.

In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - HCI, pages 62-69

DOI: 10.5220/0001700200620069

Copyright

c

SciTePress

Culture is often illustrated by using the metaphor

of an onion: the most visible outer layers are easier

to access than the hidden inner core, which is

difficult to identify (Trompenaars & Hampden-

Turner, 1997). Visible aspects of a culture are easily

recognizable for anyone. The invisible ways of

thinking and dealing with the world are much more

difficult to access. This leads to many

misunderstandings in intercultural encounters. For

example, while the greeting behaviour can be easily

observed in a different culture, it is much more

difficult to find out how a culture deals with

unavoidable uncertainties of our existence.

Cultures are often classified in accordance to

their relative positions on a number of polar scales

which cultural anthropology commonly calls cultural

dimensions. The position of a culture on those scales

is determined by the dominant value orientations.

Such quantified models of culture are difficult to

find. Hofstede originally defined four dimensions of

culture (Hofstede & Hofstede, 2005):

1. Power distance measures the extent to which

subordinates (employees, students) respond to

power and authority (managers, teachers) and

how they expect and accept unequal power

distribution. In high power distance cultures,

individuals pay more respect to superiors.

2. Individualism vs. Collectivism: these value

orientations refer to the ties among individuals

in a society. In collectivist cultures, individuals

define themselves more as members of a social

group. They are expected to share their

belongings with the group and can rely on the

backup within the group.

3. Uncertainty avoidance describes the extent to

which individuals feel threatened by uncertain

or unknown situations. High uncertainty

avoidance cultures try to avoid or prepare for

risks.

4. Masculinity vs. Femininity: these two extreme

values of this dimension focus on the

differences between the social roles attributed to

men and women and the expected behaviour of

the two sexes. Masculine values are related to

competitiveness and feminine values are related

to quality of life.

After much criticism about the Western orientation

of the whole model, Hofstede added a fifth

dimension which origins from East Asian cultures

and which is related to time: Long-term vs. short

term orientation. Long-term oriented societies are

willing to invest and wait longer for the return. In

short-term oriented cultures, individuals want to get

the return for their investment very fast (Hofstede &

Hofstede, 2005).

Trompenaars introduced another dimension

which is important: universalism vs. particularism.

Universalism means that rules are to be followed

under all circumstances. Under particularism, the

members of a culture follow relax rules according to

the circumstances (Trompenaars & Hampden-

Turner, 1997).

A dimension strongly related to individualism

vs. collectivism dimension is high vs. low context.

In a culture of low context information must be

explicitly stated. In a high context culture,

information is transferred to a large extent by

context and requires knowledge of the culture in

order to read the context information (Beneke,

2001).

There has been much criticism on the cultural

dimensions as proposed by Hofstede and others. For

example, Hofstede only considered national cultures.

However, there are often heterogeneous sub-cultures

within countries which should be considered

independently. Despite the criticism, the dimension

remain an appealing approach for researchers in

information technology because they provide a

quantitative model and they are very plausible.

The main differences between Germany and

Taiwan can be seen in table 1. We also display the

values for the USA, because the web sites of

American universities were used in the user test. It

can be observed that Germany and the USA are

much closer than Taiwan to any of the two other

cultures.

Table 1: Values of Cultural Dimension (http://www.geert-

hofstede.com).

Dimension Germany USA Taiwan

Long-term

Orientation

31 29 87

Individualism 67 91 17

Power Distance 35 40 58

Masculinity 66 62 46

Uncertainty

Avoidance

65 46 69

As an illustration for the differences between both

countries, we show the text of a Taiwanese traffic

ticket which exemplifies the values of keeping face

and the collectivistic orientation: “We beg your

pardon that we need to charge a fee from you in

order to follow the laws to maintain public order

and the security of the traffic. We hope that you

understand that and that you will see to follow the

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN TAIWANESE AND GERMAN WEB USER - Challenges for Intercultural

User Testing

63

traffic rules in the future. We wish you health and

peace.” (Chen 2004).

3 CULTURE AND WEB PAGE

DESIGN

People form their environment and create artefacts

under the influence of culture. This is also true for

information technology and especially software.

People from different cultures have different points

of views on how good systems look like (Mandl &

de la Cruz, 2008). In order to achieve good usability

and success on the market, system designers should

consider these cultural factors and adopt systems to

the target culture.

Consequently, web pages and e-commerce sites

also need to be adapted to the language and culture

of the potential user or customer. This process is

referred to as localization (Aykin 2005). Many

suggestions for the adaptation refer to simple facts

like formats, colors or symbols. Moreover,

localization also needs to consider hidden aspects of

culture (del Galdo 1996, Sturm 2005).

For research on the localization of information

systems, cultural dimensions have often been a

starting point because they provide a plausible and

quantified culture model. Marcus et al. 2003

presented examples for differences for all cultural

dimensions which are convincing. However, their

findings are based on a small and pre-selected set of

web sites. Moreover, it is not clear how cultural

dimensions may contribute to research on

intercultural web design. Some authors noted that

the assumptions made on the basis of cultural

dimensions were misleading (Griffith 1998).

An early study of Barber & Badre (1998) tried to

find typical cultural markers in an inductive

approach. The approach of Marcus et al. (2003)

started with knowledge on cultural dimension in

general and intended to locate effects within web

sites. This could be labelled a deductive approach.

Cultural markers are also procured by Sun (2001).

His study which included interviews about certain

homepages showed that the presence of cultural

markers increased the aesthetic satisfaction with a

web site. However, only few users were interviewed

(Sun 2001).

The methodology for intercultural research is

especially problematic. What is measured in a

human-computer interaction experiment in an

intercultural setting? Can good vs. bad design be

determined or can usability or typical design for one

culture or another be identified? Empirically

convincing studies are difficult to set up from a

methodological point of view. In common

quantitative human-computer interaction studies,

two versions of a user interface are presented to two

user groups who are selected from the same culture

and who are believed to be homogeneous. For

comparative studies in international web design

analysis, the user groups are different and their

reaction to the system is under investigation.

However, it is difficult to leave the system constant.

The system cannot be presented to two groups of

users from different countries without modification.

The system needs to be translated and culturally

adapted. For example, the investigated task may be

embedded completely differently in the two cultures.

Typical user groups like university students may

have quite different features like social group in

different societies. Hence, the system often needs to

be changed significantly in order to be adequate for

a real-life experiment which makes comparability

difficult (Evers 2002). This is a general problem is

intercultural research (Eckensberger & Plath, 2003).

In order to overcome these problems, sometimes

expatriates are used as test users (Sheppard &

Scholtz,, 1999). For tests with e-learning systems,

foreign students can be used (Kamentz & Womser-

Hacker, 2003, Kamentz & Mandl, 2003). This

method may relax the problem of the language

barrier, however, it needs to be emphasized that

language competency in a second language is not

comparable with the language competence in a

native language. Another way to overcome the

methodological problems is the use of mock-up

systems instead of real-life web pages (e.g. in

Sheppard & Scholtz 1999, Hodemacher 2005). The

drawback lies in the artificiality of the experiment.

One further method is the use of pages which are in

a foreign language for all test users (e.g. Schmitz

2005, Dormann & Chisalita 2002). Dormann &

Chisalita try to quantify the differences between the

perception of test users from different cultures and

the design of web sites from other countries. Their

analysis is focused on the dimension femininity vs.

masculinity for university web sites in Italy and

Scandinavia.

A different methodological approach is adopted

by Kralisch & Berendt (2004). They used web log

mining to infer preferences of users. Web log mining

exploits the log files which ware automatically

collected when users access web sites. They could

show, for example, that users from long-term

oriented cultures are more likely to use browsing

than keyword search (Kralisch & Berendt, 2004).

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

64

Key word search leads to the goal faster, however,

browsing through an ontology might help the user

with orientation within an information system at

future search tasks. The time invested for getting to

know the system is invested and the users hope for a

return in the future. They assume that knowing the

system will facilitate their future searches. Long-

term oriented cultures are more willing to invest this

extra effort whereas short-term oriented cultures

tend to value quick access to information more

highly. They rely more on key word searching.

The ultimate goal of studies which intend to

reveal effects of culture on web site design and

perception is the design of optimal systems. The

influence of culture needs to be measured and later

applied to user interface design.

4 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

We conducted a user test in Taiwan and Germany in

order to determine differences in the perception of

web sites and preferred navigation techniques. We

chose university students as test subjects because

they are easy to recruit. Students are usually

considered to be a group which has comparable

socio-economic features. However, even that may

not be the case in cultures which are far apart.

Although the const of living for students is much

higher than in Germany and tuition is also higher,

the percentage of students within the society is

higher in Taiwan.

The tasks for the user test were chosen to be

natural for university students. We created a

scenario in which the student wants to study abroad

and needs to acquire information from American

universities. This is a natural task for both German

and Taiwanese students because from both groups

many individuals study in the USA at some point in

time. Nevertheless, Taiwanese students are likely to

gather such information from informal sources like

personal contacts rather than from web sites. By

choosing queries on American universities (Babson

College, Adams College, Cedarville University) as

natural tasks, we also managed to have comparable

information systems for the user test. We needed no

artificial web sites nor translation of web sites from

one language to another. We selected only students

with at least good English language skills. The

selected universities are the Babson College, the

Adams College and the Cedarville University. These

three sites differ in their web site design and

represent conservative as well as innovative designs.

The site of the Butler University was used in

addition because it displays its main menu on the

right side. This might be preferred by Taiwanese

students because it goes along with the Chinese

reading direction from right to left. The site of the

American education ministry was included in one

search task.

The groups of test persons in Germany as well as

in Taiwan needed to interact with web sites which

were in a foreign language and which were not

developed for their particular culture. We believe

that this is a good strategy to determine differences

in web site perception in a comparative test.

Certainly, it is not an adequate strategy to determine

the most appropriate design for one specific culture.

For this study, 24 students both from Taiwan and

Germany were recruited. All test persons were

between 20 and 30 years old. The majority fell into

the age group between 23 and 24. In both test

groups, both sexes were almost equally represented.

Almost one third of the Taiwanese students and one

fifth of the German students had visited the USA

prior to the test. Nevertheless, the Taiwanese

students graded their English competence almost

one grade lower than the German students. The test

in Taiwan and Germany was conducted in English

which seems to be a valid method (Dray, 1996). A

control group of additional German students was

tested in English in order to measure the quality of

the foreign language material.

The test consisted of a pre-interview, two search

tasks for all three universities and finally an

interview and a questionnaire about the sites, tasks

and performance. Thinking aloud was encouraged

before the test. Six search tasks typical for the

information needs of foreign students were designed.

A typical test task was: Which MBA programs are

offered at College X? A time limit of three minutes

was set for this task. Another task was: Which kinds

of stipends are offered at College Y?

5 RESULTS

The results are based on the objective measures and

the subjective ratings provided by test subjects.

5.1 Performance Measures

Task completion was measured for all six tasks.

Overall, the performance was satisfying and

Taiwanese students performed worse as shown in

table 2. For one task, the difference was significant

with a error probability below 1%.

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN TAIWANESE AND GERMAN WEB USER - Challenges for Intercultural

User Testing

65

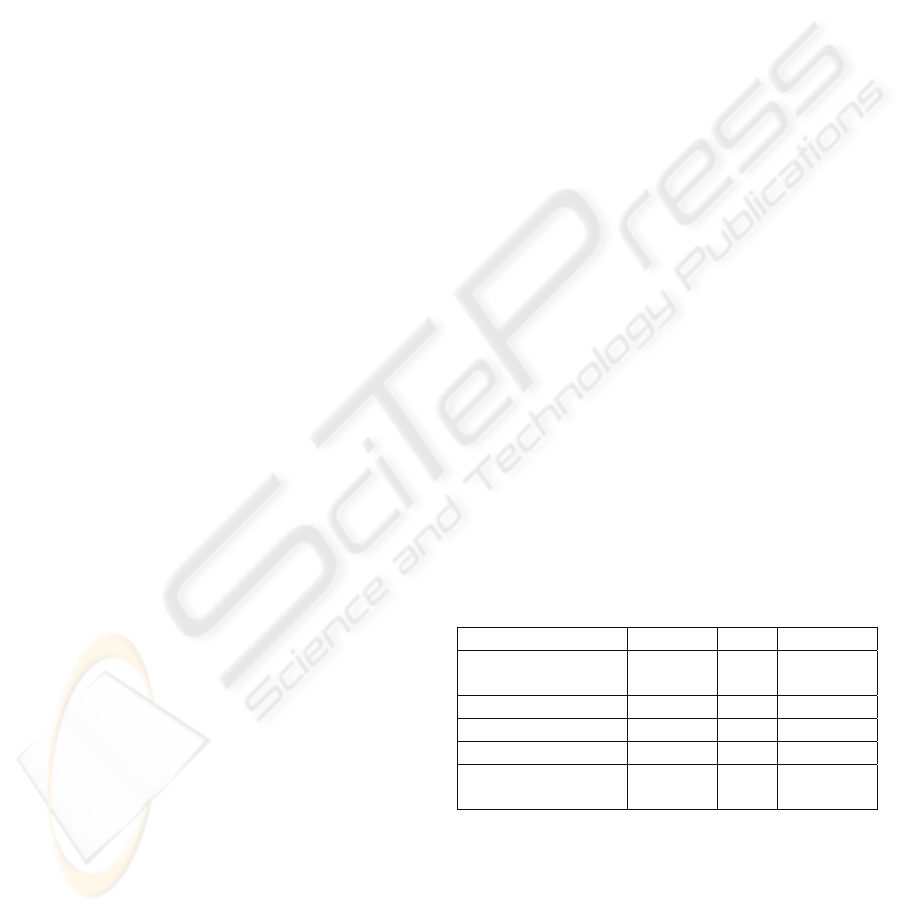

Table 2: Task Completion. Significant difference between

groups is marked with *.

Task Taiwanese students German students

1 75% 87.5 %

2 29.2% 50%

3

83.3%

100%

4*

41.7% 83.3%

5

75% 87.5 %

6

75% 87.5 %

This confirms the hypothesis that German students

get along better with the American web sites

because the two cultures are similar. This result is

confirmed by remarks of Taiwanese test students

who found the American sites “completely

different” than Chinese or Taiwanese sites. The

same cultural adequacy is supported by the

completion time of those test subjects who finished

the tasks. It can be seen that the German students

were mostly faster. For four tasks, the difference is

statistically significant according to a T-test.

tim e in seconds

tasks

German

Taiwanese

Figure 1: Task Completion Time.

To investigate the influence of testing in a foreign

language, a German verification group was tested

with the test material in their native tongue. Within

this group, the task completion time was only for

two tasks below the task completion time in the test

with English. The only statistically significant

difference was found for a task for which the

German group was slower.

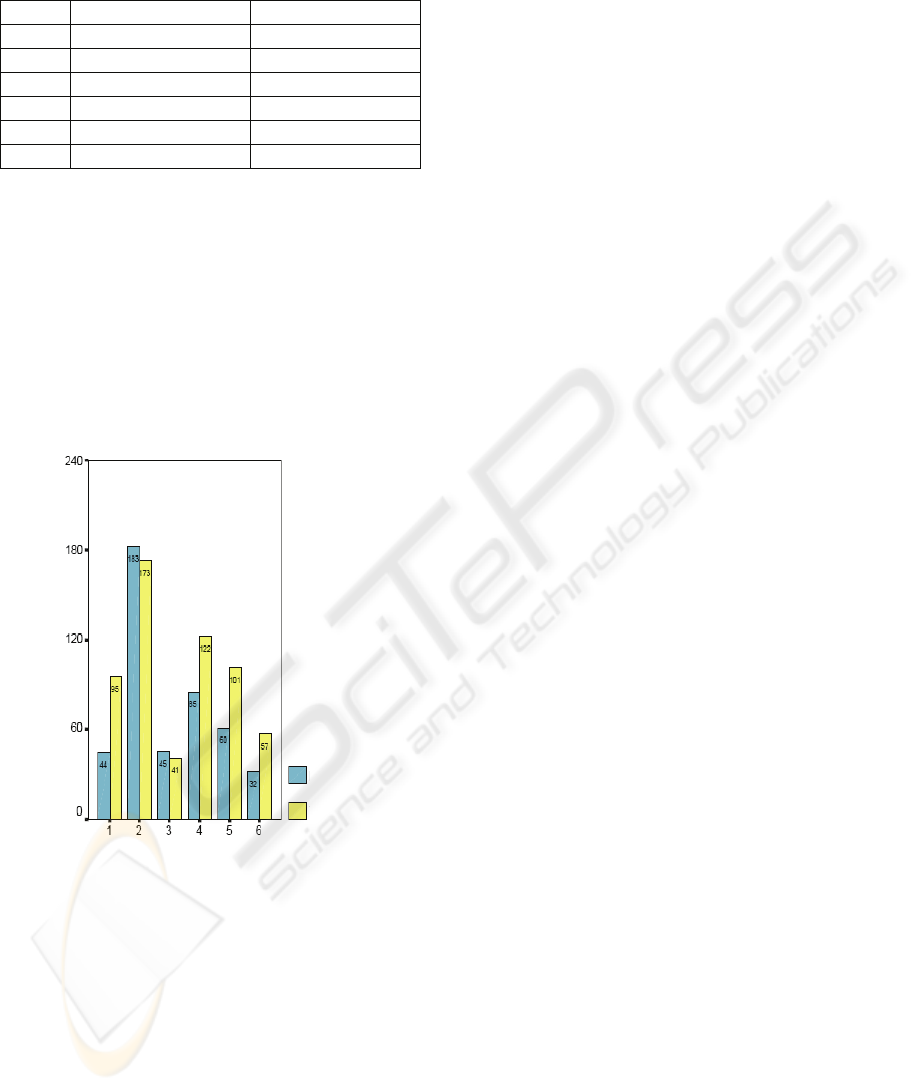

It was expected that the Taiwanese would take

longer to complete the tasks. At the same time, it

was assumed that they would tolerate the longer

completion time due to the long-term orientation of

their culture. This was examined with a post test

questionnaire. Test subjects were asked whether they

agree with the following statement: “I found all

necessary information in due time”.

Contrary to the hypothesis, Germans tend to

agree stronger with this statement on a six-point

scale. The difference is even statistically significant.

However, this result must be interpreted under

consideration of the task completion figures. The

agreement with the statement correlates strongly

with success of the test person for the corresponding

task. The following figure shows the answers of

Taiwanese students for task six. The students who

finished the task and the students who did not finish

the task are marked with different colours.

There are not enough students who finished the task

to conduct a statistical test. The hypothesis that

Taiwanese students as members of a long-term

oriented culture are more patient during their search

tasks and that they are willing to invest more time

cannot be proven statistically. However, we tend

accept this hypothesis. The Taiwanese students took

also more time to fill out the questionnaire and

ended up with a longer overall test time (75 minutes

compared to 45 minutes). They invest more time and

expect a better performance in the future. They are

more oriented toward long-term success than short-

term performance.

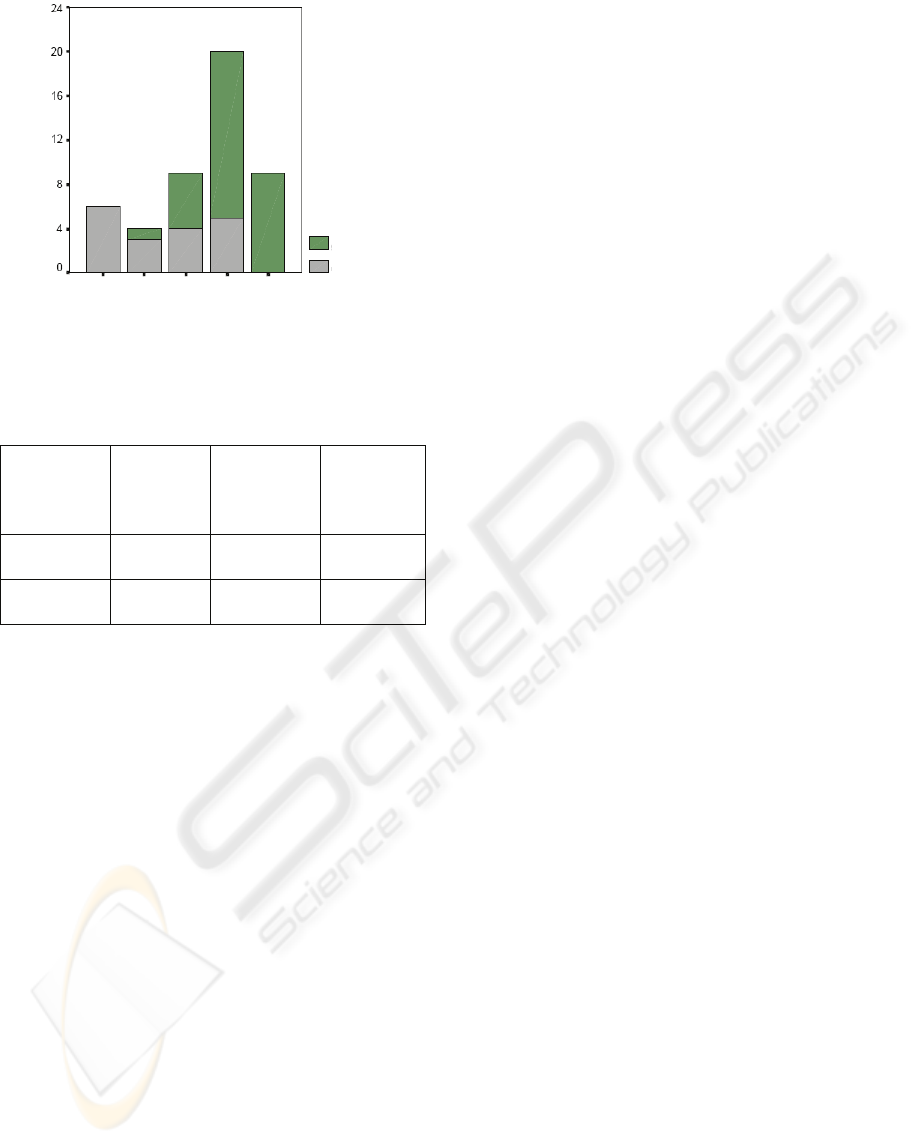

5.2 Preferred Search Method

Based on results from previous research, we

formulated a hypothesis that Taiwanese students

would use browsing options more often for finding

the result. Long-term oriented cultures seem to tend

to use links in order to have better orientation

whereas members of short-term oriented cultures

tend to use keyword searches more often because

they emphasise short-term success over long-term

learning.

This hypothesis could not be verified. Germans

relied more on links than the Taiwanese students

who tended to use site search functions more often.

However, the differences shown in table 3 are not

statistically significant. The utterances during the

test confirm that the hypothesis needs to be rejected.

Taiwanese students explicitly stated that they used

keyword search because it is faster. At the same

time, Germans stated that they want to get

orientation. Maybe uncertainty avoidance also

influences the search options used. In addition, bad

experiences with search systems need to be

considered as well. Further research is necessary.

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

66

Number of students

finished

not

finished

task

d

o

n

o

t

a

g

r

e

e

r

a

t

h

e

r

n

o

t

a

g

r

e

e

r

a

t

h

e

r

a

g

r

e

e

d

o

a

g

r

e

e

f

u

l

l

y

a

g

r

e

e

Figure 2: Task completion and subjective rating.

Table 3: Search Options.

Search

Options

mainly

keyword

search

keyword

search as

well as

links

mainly

links

Taiwanese

students

25.0 % 20.8 % 54.2 %

German

students

16.7 % 8.3 % 75,0 %

The links followed during the test were

categorized as text or graphic links. A hypothesis

was formulated, that Taiwanese students would

rather use graphic links because they are from a high

context culture. The pages contained few graphic

links overall. Consequently, most links used were

text links. However, five out of 24 Taiwanese

students used graphic links and only one out of 24

Germans. The data supports the hypothesis but

statistically significance cannot be achieved.

For one search task, the test persons had the

choice of either using a standard search engine like

Yahoo and Google or the search page of the ministry

of education. The high power distance in Taiwan

suggests that Taiwanese students would rather use

the authoritative search engines from the ministry.

This is indeed the case. Only 52.4 % of the Germans

used the ministry search compared to 62.5 % of the

Taiwanese. However, the difference is not

statistically significant (T-Test).

5.3 Information Design

Two questions on the questionnaire tried to find out

whether the users were satisfied with the information

present on the pages. High context cultures might

require less information than low context cultures

like Germany. Test persons were asked whether

there was sufficient information on the pages and

whether there was too much information. No

significant result supporting the hypothesis was

found. This might be due to the test design. Germans

might have been satisfied with the level of

information because they are from a culture similar

to the culture of the web sites. The Taiwanese

students might have been satisfied with even less

information but did not feel that it was too much.

Too little information on a page might be seen as

more negative. A test with pages from a culture with

even higher context might be helpful. Not all

deviations from the preferred model are interpreted

equally. This result has also been obtained by other

experiments (Dormann & Chisalita, 2002).

Students were asked whether they find

information on the administration of a university to

be important. Students from Taiwan with a higher

power distance might find such authoritative

information more important. This is indeed the case.

Taiwanese students assigned an importance grade of

3.63 on the six point scale from 0 to 5.0 whereas the

Germans assigned a lower average grade of 2.0. The

observed difference proved to be statistically

significant (T-Test, 1% error probability).

One web site had a menu on the right side. The

attitude towards this for Westerners unusual position

was queried in the questionnaire. Taiwanese students

overwhelmingly thought that this position is

acceptable (87.5 %) while only about half of the

Germans found it acceptable (47.8 %). The

difference is statistically significant (T-Test, 1%

error probability).

Animations were used on one site and they were

evaluated much more negatively by Taiwanese

students.

6 CHALLENGES FOR

INTERCULTURAL USER

TESTS

The test showed that cultural distance seems to lead

to a decrease in performance during the human-

computer interaction with web sites. Some

differences might be caused by cultural reasons

other than the perception of the web site. These

problems make such test difficult and need to be

considered during test design.

Students were asked to grade their knowledge of

English. On average, the Taiwanese students

selected almost one grade lower than the German

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN TAIWANESE AND GERMAN WEB USER - Challenges for Intercultural

User Testing

67

students although the Asians have more travel

experience in the USA. This is likely to be due to the

modesty required by the culture which is rooted in

collectivism. This assumption is supported by

utterances during the test. One student from Taiwan

said: “I can’t take very good, can I?” Modesty leads

generally to a situation in which Asians tend to

assign less extreme grades in questionnaires (Evers

2002). This effect may have skewed some of the

results obtained by questionnaire. It seems necessary

to modify the scales offered for both groups. This is

done for social science surveys (Iwai, 2005).

The main problems caused for the test in Taiwan

were due to the importance of face keeping in the

culture. Test subjects were reluctant to use the

thinking aloud method because they might reveal a

personal mistake. Similar observations have been

reported before (Evers, 2002). Group tests are

sometimes mentioned as a means to alleviate these

issues, however, they might be seen as a competitive

test situation and make test subjects even more

uncomfortable. The test situation might even have

led to some discomfort because a woman was

conducting the user test in Taiwan.

An important factor is that also objective data

and its relation to subjective data needs to be

interpreted within the context of the culture.

Subjective and objective data measure different

aspects of usability and do not always lead to the

same preference (Hornbæk & Law, 2007). In

intercultural user test settings, the relation depends

on the culture. For non-repetitive tasks like

explorative searching, the time spent on the task

might not be felt as negative by long-term oriented

cultures.

7 CONCLUSIONS AND

OUTLOOK

Our study clearly indicated that users from different

cultures perform tasks differently on the same web

sites. The differences can often be interpreted within

cultural models like the dimension of Hofstede.

Some previous findings on cultural differences could

be confirmed, others could not be supported by our

findings. The preferences of search options based on

long- vs. short-term cultures as well as the

preference of high context cultures for rich

representations could not be supported. On the other

hand, the effect of power distance on the content of a

web site was confirmed. The users from a culture

more similar to the culture of the tested sites had

better results which might be due to their cultural

closeness.

Many difficulties of international user testing

were identified. Results need to be interpreted within

the culture of the users. Merely statistical analysis

might give to misleading results. However, many

more studies are necessary to gain more insight into

the consequences of different cultures on the

creation and usage of software systems. In the

context of the globalization, the topic is more and

more important.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. Wu Ling-Ling

from the National Taiwan University for her great

support during the preparation and the

implementation of the user test in Taiwan.

REFERENCES

Aykin, N., 2005. Usability and Internationalization of In-

formation Technology. Mahwah, New Jersey: LEA

Barber, W., Badre, A., 1998. Culturablity: The Merging of

Culture and Usability. In Proceedings of the Fourth

Conference on Human Factors and the Web.

http://www.research.att.com/conf/hfweb/proceedings/

barber/

Bortz, J.; Döring, N., 1995. Forschungsmethoden und

Evaluation für Sozialwissenschaftler. Berlin: Springer

Chen, H. 2004. KulturSchock China. Bielefeld: Reise

Know-How

Choong, Y. ; Salvendy, G., 2000. Implications for Design

of Computer Interfaces for Chinese Users in Mainland

China. In International Journal of Human-Computer

Interaction. vol. 11 (1) pp. 29-46

Choong, Y-Y.; Plocher, T.A., Rau, P-L.P., 2005. Cross-

cultural Web Design. In Procter, Robert (Ed.).

Handbook of Web Design. LEA.

Dormann, C., Chisalita, C., 2002. Cultural Values in Web

Site Design. In Proc Eleventh European Conference

on Cognitive Ergonomics (ECCE 11) Catania, Italia,

Sept. 8-11.

Del Galdo, E., 1996. Culture and design. In Del Galdo, E.,

& Nielsen, J. (Eds.): International user interfaces.

New York et al.: Wiley.

Eckensberger, L., Plath, I. 2003. Möglichkeiten und

Grenzen des variablenorientierten Kulturvergleichs:

Von der Kulturvergleichenden Psychologie zur

Kulturpsychologie. In Kaelble, H., Schriewer, J.

(eds.): Vergleich und Transfer – Komparatistik in den

Sozial-, Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften.

Frankfurt: Campus. pp. 55-99.

Evers, V., 2002. Cross-Cultural Applicability of User

Evaluation Methods: A Case Study amongst Japanese,

ICEIS 2008 - International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

68

North-American, English and Dutch Users. In

Proceedings ACM CHI Conf. pp. 740-741.

Griffith, T.L. 1998. Cross-Cultural and Cognitive Issues in

the Implementation of New Technology: Focus on

Group Support Systems and Bulgaria. In Interacting

with Computers. Special Issue: The Role of Culture in

the Globalisation of Human-Computer Systems. v.9

n.4 pp. 431-447.

Hodemacher, D., Mandl, T., Jarman, F., 2005. Kultur und

Web-Design: Ein empirischer Vergleich zwischen

Großbritannien und Deutschland. In Auinger, A. (ed.):

Workshop-Proceedings der 5. fachübergreifenden

Konferenz Mensch und Computer. Linz, Austria.

September 2005. pp. 93-101.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., 2005. Cultures and

Organizations: Software of the Mind. 2., erw. und

überarb. Aufl. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hornbæk, K.; Law, E., 2007. Meta-analysis of correlations

among usability measures. In Proceedings of the

SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing

systems (ACM Press) San Jose, CA, pp. 617-626.

Iwai, N., 2005. Japanese General Social Surveys (2):

Methodological Experiments in Administering the

Questionnaire, Incentives, Scales and Wording: In ZA-

Information (57) Nov. pp. 83-103.

Kamentz, E., Mandl, T., 2003. Culture and E-Learning:

Automatic Detection of a Users’ Culture from Survey

Data. In: Evers, V., Röse, K., Honold, P., Coronado,

J., Day, D. (eds.): Designing for Global Markets 5:

Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on

Internationalization of Products and Systems (IWIPS

2003) 17-19 July, Berlin. pp. 227-239.

Kamentz, E.; Womser-Hacker, C., 2003. Using Cultural

Differences in Educational Program Design and

Approaches to Computers for Adaptation Concepts of

Multimedia Learning. In Stephanidis, C. (Ed.) (2003),

Universal Access in HCI: Inclusive Design in the

Information Society. Proceedings of 10

th

International

Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 22-27

June 2003, Crete, Mahwah, NJ; LEA , pp. 1128-1132.

Kim, D-W., Eibl, M., Mandl, T., 2005. How Do Web Sites

Appear in Different Cultures? A Comparative Study

with Korean and German Users. In Proceedings of the

11

th

International Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction (HCI Intl.): Las Vegas, 22.-27. Juli.

Mahwah, NJ; London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Volume 10 - Internationalization, Online Communities

and Social Computing: Design and Evaluation.

Kralisch, A.; Berendt, B., 2004. Cultural Determinants of

Search Behaviour on Websites. In Evers et al. (eds):

International Workshop on Internationalisation of

Products and Systems (IWIPS). pp. 61-74

Kroeber, A.; Kluckhofen, C., 1952. Culture: A Critical

Review of Concepts and Definitions. New York:

Random House

Law, E., Hvannberg, E. 2004. Analysis of Combinatorial

User Effect in International Usability Tests. In Procee-

dings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in

computing systems (ACM Press) Vienna, pp. 9-16.

Mandl, T., de la Cruz, T., 2008. International Differences

in Web Page Evaluation Guidelines. In International

Journal of Intercultural Information Management

(IJIIM) vol. 2. to appear.

Marcus, A.; Baumgartner, V.; Chen, E., 2003. User Inter-

face Design vs. Culture. In International Workshop on

Internationalisation of Products and Systems (IWIPS)

pp. 67-78

Schmitz, K. 2005. Kulturelle Unterschiede bei der Benut-

zung und Bewertung von Websites am Beispiel von

Deutschland und Taiwan. Master Thesis, International

Information Management. University of Hildesheim,

http://web1.bib.uni-

hildesheim.de/edocs/2006/505460009/meta/

Sheppard, C., Scholtz, J., 1999. The Effects of Cultural

Markers on Web Site Use. In Proceedings of the 5th

Conf on Human Factors & the Web. 3 June.

Gaithersburg,Maryland.

http://zing.ncsl.nist.gov/hfweb/proceedings/sheppard

Sturm, C., 2005. Approaches for a successful product

localization. In Auinger, A. (ed.): Workshop-

Proceedings der 5. fachübergreifenden Konferenz

Mensch und Computer. Linz, Austria. September

2005. http://mc.informatik.uni-hamburg.de/konferenz

baende /mc2005/workshops/WS8_B1.pdf

Sun, H., 2001. Building A Cultural-Competent Corporate

Web Site: An Exploratory Study of Cultural Markers

in Multilingual Web Design. In SIGDOC’01. 21-24

October. Santa Fe, NM: ACM. pp. 95-102

Trompenaars, F.; Hampden-Turner, C., 1997. Riding the

Waves of Culture: Understanding Cultural Diversity

in Business. London: Nicholas Brealey.

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN TAIWANESE AND GERMAN WEB USER - Challenges for Intercultural

User Testing

69