WHO SHOULD ACCESS ELECTRONIC PATIENT RECORDS

A. Ferreira

1,2

, L. Antunes

2

, C. Pinho

3

, C. Sá

3

, E. Mendes

3

, E. Santos

3

, F. Silva

3

, F. Sousa

3

F. Gomes

3

, F. Abreu

3

, F. Mota

3

, F. Aguiar

3

, F. Faria

3

, F. Macedo

3

S. Martins

3

and R. Cruz-Correia

3

1

Computing Laboratory, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent, CT2 7NF, UK

2

Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Science, University of Porto, Portugal, partially supported by KCrypt

(POSC/EIA/60819/2004) and funds granted to LIACC through Programa de Financiamento Plurianual, FCT and

Programa POSI.

3

Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto and CINTESIS, Portugal

Keywords: Electronic Patient Record, access control, attitudes.

Abstract: Access control to Electronic Patient Records (EPR) may greatly depend on users’ objectives and needs. The

purpose of this study is to assess the opinions of medical doctors within a university hospital towards access

control to an EPR. We selected a randomized sample of 58 doctors from a university hospital and 45

structured interviews were applied. 42 respondents (93%) agree with the existence of access control levels

to patient information according to healthcare professionals’ category and 31 (69%) think that more

sensitive information (e.g. HIV) should be accessed only by doctors that treat those patients. As 24 doctors

(53%) feel that there is no need for them to see all information about all the patients, 41 (91%) think that

nurses should not be able to do it also. Further, 31 doctors (69%) believe that patients themselves should not

access their full medical record. These results show that it is very hard to get to a consensual policy

regarding access control to EPR by its regular users. There is therefore the need for a multidisciplinary

agreement that can include healthcare professionals’ experiences and needs in order to define the most

appropriate and efficient way to perform access control to the EPR.

1 INTRODUCTION

Good communication between health providers is an

essential component of high quality health care

(Hassol et al., 2004) Paper-based medical record is

still widely used in hospitals, where health

professionals gather patient’s clinical and

administrative information. There is however some

problems with this type of records and so computer-

based medical records are being implemented and

used in a more regular basis (Bakker et al., 2004).

The evolution of technology allows health

providers to communicate electronically and to obtain

information which includes patient’s health story,

examination findings, diagnosis and treatment over a

period of time (Hassol et al., 2004) (Day, 2001).

This enabling technology that constitutes the

informational basis for communication and

cooperation in and between healthcare organizations

is called Electronic Patient Records (EPR) (Ab et al.,

2004).

However, this wide use of information systems

and technologies shows the need for healthcare

organizations to integrate and manage information

from various sources, types and formats. This

reflects the careful scrutiny that electronic access to

medical information requires (Rogerson, 2000).

Information security is then essential, moreover

when people accessing the EPR can have varied

objectives, different types of access and several

processes to execute. Therefore, access control is

essential to provide because it manages one of the

first contacts between users of a system and its

functionalities and features (Ferreira et al., 2005)

(Ferreira et al., 2006).

According to a recent report, more than 1000

accidental deaths have been attributed to computer

system failure (Gritzalis, 1997). Such occurrences

must be present when considering the different

interests and objectives that users want to achieve

when using the EPR.

The Biostatistics and Medical Informatics

Department of Porto’s Faculty of Medicine

182

Ferreira A., Antunes L., Pinho C., S

´

a C., Mendes E., Santos E., Silva F., Sousa F., Gomes F., Abreu F., Mota F., Mota F., Aguiar F., Faria F., Macedo F.,

Martins S. and Cruz-Correia R. (2008).

WHO SHOULD ACCESS ELECTRONIC PATIENT RECORDS.

In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Health Informatics, pages 182-185

Copyright

c

SciTePress

implemented a centralized EPR system (VEPR –

Virtual EPR) between May 2003 and May 2004 in

Hospital S. João (HSJ), Porto, Portugal. This

hospital has more than 1300 beds and 5000 workers

from 56 departments, where about 1000 are medical

doctors, so any access to information needs to be

properly defined, controlled and monitored. A generic

but strong access control policy that reflects people’s

processes and interactions with the system, without

incapacitating its use, is the basis for the VEPR

success and, more importantly, acceptance, trust and

use (Ferreira et al., 2005) (Ferreira et al., 2006). More

than 900 doctors access this system on a daily basis,

and this number is increasing, as healthcare

professionals can feel the benefit from its use.

Even patient’s access to their health records is

now common in many places (Tracyl et al., 2004)

(Pyper et al., 2004). How is access control going to

be modelled in all these cases?

In this article we aim to get a small glimpse of

what are the opinions of doctors working in HSJ

towards who should access Electronic Patient

Records, how should it be done and for whom this

information should be (or not) restricted.

2 METHODS

2.1 Type of Study

This is an observational, descriptive, transversal

study, in which the analysis unit is the individual.

2.2 Participants’ Selection

Initially, we performed a bibliographic search of

publications concerning access control to Electronic

Patient Records. The next step was the selection of

participants. Our target population was medical

doctors. The available representative population was

the medical doctors of the HSJ from a list available

from the department of human resources at HSJ.

From that list the medical doctors, department

directors and pre-career doctors were selected. As a

sampling method, from the filtered list, we selected

a simple randomized sample of 92 elements.

2.3 Data Collection

The instrument used for data collection was a

questionnaire with the characteristics of a structured

interview, which was absolutely anonymous. The

first steps in the questionnaire design were the

research of questionnaires previously tested and the

elaboration of a variable list.

The questionnaire was then pre-tested, in order

to evaluate its validity and reproducibility. The pre-

test’s participant selection was made by a non-

random accidental sampling process. The

interviewer asked 10 HSJ doctors, who were at the

hospital at that moment, to fill it in. Then, the final

version of the questionnaire was elaborated with the

pre-coded variables.

The questionnaire comprises 8 questions, some

of them subdivided (see Apendix). The first 2

questions are global questions where doctors

indicate the frequency they use the EPR and if there

should be several access levels to records depending

on the health professional’s category (a Yes or No

response).

Question 3 refers to doctors’ access

control and question 4 refers to the access to more

sensitive information about patients (like HIV tests).

Question 5 demanded doctors’ opinions about

nurses’ access to EPR. Questions 6, 7 and 8 describe

other situations such as emergency situations, other

uses of EPR and patient’s access to their EPR.

The independent variables potentially relevant

for the statistical analysis are: age, gender,

professional category and department. This

information was used to compare answers to the

different questions (dependent variables) between

these distinct groups in the statistical analysis.

The following step was the recruitment.

Different departments were visited in order to find

the doctors that were part of the sample. Those who

did not work in HSJ anymore (29 people) or were

already retired (5 doctors) were excluded, and the

sample was reduced to 58 people. Then, the

questionnaire was applied. If the doctors were not

available at their department after three attempts,

refused to answer the questionnaire or left it

incomplete, they were eliminated from the study.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

In what concerns statistical analysis, we used SPSS

to insert the collected data in a preformatted table

.

We started to analyse our sample using absolute

and relative frequency tables as well as pie graphs.

Chi-Square tests were also performed in order to

evaluate the significance of the differences found

between ages, genders, professional categories and

departments, regarding the most relevant questions.

As there are cases that do not respect the qui-square

test’s assumption (that require all expected values to

be equal or superior to 5), some values are

calculated using Fisher’s exact test.

All the independent variables used in this study

are categorical variables, except the age. In order to

facilitate the data analysis, we transformed this

numerical variable in a categorical one.

WHO SHOULD ACCESS ELECTRONIC PATIENT RECORDS

183

Furthermore, some independent variables were

attached in categories so that we could perform a

chi-square test. The variable age was separated in

two categories: under 35 and over 35. We chose 35

as the dividing age because most doctors become

specialists at that age. Professional categories were

also divided in two categories: pre-career doctors

and medical doctors. Departments were categorized

in medical departments or medical – surgical. The

significance level used in this study was 0.05.

3 RESULTS

Of the 58 applied questionnaires, 45 were fully

answered, so the response rate was 78%. 10 doctors

were not available in the department for three

consecutive times and 3 refused to answer.

Participants’ characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Most doctors were over 35 years old and there were

more female doctors than male doctors.

Table 1: Respondents’ demographics (N=45).

Age <35

>35

22%

78%

Gender Male

Female

58%

42%

Department Chirurgic

Medical

38%

62%

Professional

Category

General Intern

Specialist Intern

Specialist

Graduated Specialist

Service Director

7%

9%

38%

36%

11%

All doctors confirmed that they have already

used EPR. Most of them said that they use this kind

of records daily and that they agree with the

existence of different access levels of information

depending on the healthcare professional’s category.

93% (3) of the doctors said they agree and 7% (42)

answered they do not agree or have no opinion

regarding this issue.

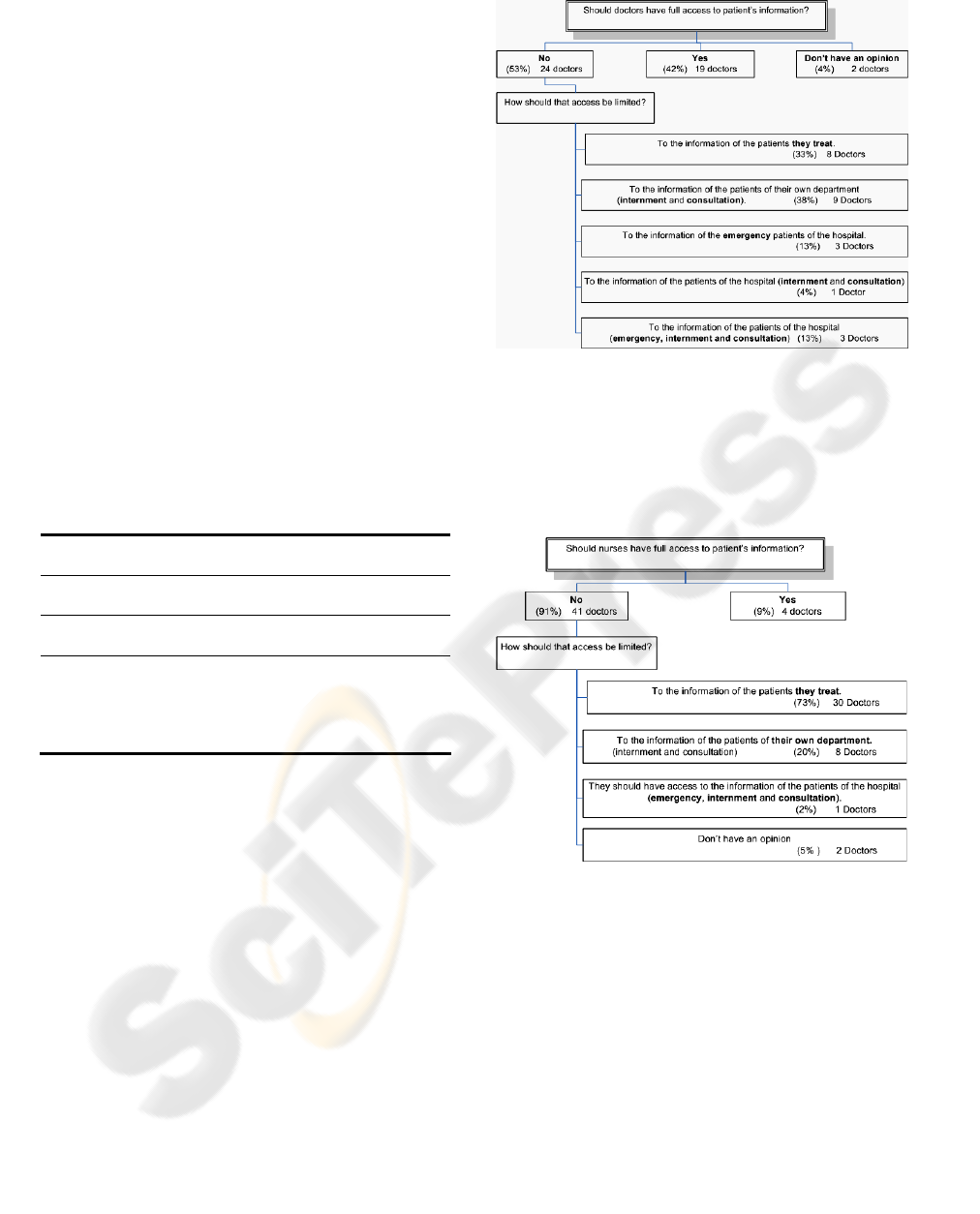

In what concerns doctors’ access to information,

the answers are summarized in Figure 1. More than

a half of the respondents thought that doctors should

not have full access to patients’ information. While

some thought that doctors should only have access

to the information of the patients they treat, others

considered that they should have access to all the

information of their department.

Further, 31 (69%) respondents thought that

sensitive information such as HIV tests, venereal or

cancer diseases should only be accessed by doctors

who treat those patients.

Figure 1: Answers for doctors’ access to a full EPR.

In what concerns nurses (Figure 2), a vast

majority of doctors (41 - 91%) thought that they

should not have full access to patients’ information.

The majority believe that nurses should only have

access to the information of the patients they treat.

Figure 2: Answers for nurses’ access to a full EPR.

Most doctors also agreed that, in emergency

situations, non authorized doctors and nurses must

have access to patients’ information, but that access

must be registered and controlled (Ferreira et al.,

2006). The majority of respondents found pertinent

to use the patients’ records to other purposes such as

clinical or epidemiologic investigation.

Regarding now patients, most doctors thought

that patients should not have full access to their

clinical information, 69% (31) thought that they

should not be able to access it while 31% (14) said

that they should.

HEALTHINF 2008 - International Conference on Health Informatics

184

4 CONCLUSIONS

From these results we can see that EPR are intensely

used by doctors. We can also discuss that doctors are

mostly concerned with situations regarding sensitive

information (e.g. HIV tests), and patients’ access to

these type of records. This is why they see access

control as an essential part of the EPR.

Also, doctors do not agree with the fact that

patients should be able to access the whole of their

healthcare record, thinking probably some of the

notes they make should be for they own use only.

This opinion is also demonstrated in another study

where they seem to be worried about the information

accessed by their patients.

Further, doctors were reluctant in what concerns

nurses’ access to patients’ information. They think

they should only access the information of the

patients they treat. This can be problematic as nurses

spend more time dealing and treating patients than

the doctors themselves and may need all the

information about the patient relating to other types

of treatment they can had been undergoing. It should

be noted that all doctors had an opinion regarding

this matter.

Our study also shows a tendency between some

variables. It is interesting to note that, within the 4

doctors who think that nurses should have total

access to information, 3 were male doctors and 3

were specialists.

Finally, doctors’ attitudes towards the use of

information for other purposes such as research were

mostly positive. They also vastly agreed with the

existence of different levels of access to EPR.

In conclusion, these results show that it is very

hard to get to a consensual policy regarding access

control to EPR by its regular users.

There is therefore the need for a

multidisciplinary agreement that can include

healthcare professionals’ experiences and needs in

order to define the most appropriate and efficient

way to perform access control to the EPR. Several

issues concerning the type of information, location,

type of user and other situations (e.g. emergency or

other unanticipated) may influence the way access

control should be made.

We believe that this is a very important issue to

be pursued and further studied. There is the need to

evaluate more healthcare professionals and patients’

attitudes and needs in order to define a better way to

perform access control to EPR (Ferreira, Cruz-

Correia et al., 2006).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank class 8 of the 1

st

year

medical students from the 2005/2006 academic year

at the Biostatistics and Medical Informatics

Department of the Faculty of Medicine of Porto for

their work and enthusiasm in the development of

this project.

REFERENCES

Ab, B., Addabit, B.V., 2004. Access to EHR and access

control at a moment in the past: a discussion of the

need and an exploration of the consequences.

International Journal of Medical Informatics, 73, 267-

270.

Blobel, B., 2004. Authorisation and access control for

electronic health record systems. International Journal of

Medical Informatics, 73(3): 251-257.

Day, J., 2001. Privacy and Personal Health Data in

Cyberspace: the Role and Responsibility of Healthcare

Professionals. The journal of contemporary Dental

Practice, 2(1).

Ferreira, A, Cruz-Correia, R., Antunes, L., Chadwick,

D.W., 2007. Access Control: how can it improve

patients' healthcare? Studies in Health Technology and

Informatics. IOS Press, 127:65-76.

Ferreira, A., Correia, R., Antunes, L., Palhares, E.,

Farinha, P., Costa-Pereira, A., 2005. How to start

moddeling Access Control in a Healthcare

Organization. Proceedings of the 10th International

Symposium on Health Information Management

Research.

Ferreira, A., Cruz-Correia, R., Antunes, L., Farinha, P.,

Oliveira-Palhares, E., Chadwick, D. W., Costa-Pereira,

A., 2006. How to break access control in a controlled

manner? Proceedings of the 19th IEEE Symposium on

Computer-Based Medical Systems, 847-851.

Gritzalis, D., 1997. A Baseline Security Policy for

Distributed Healthcare Information Systems. Computers

and security, 16(8):709-719.

Hassol, A., Walker, J., Kidder, D., Rokita, K., Young, D.,

Pierdon, S., Deitz, D., Kuck, S., Ortiz, E., 2004. Patient

Experiences and Attitudes About Access to Patient

Electronic Healthcare Record and Linked Web

Messaging. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 11, 505-513

Pyper, C., Amery, J., Watson, M., Crook, C., 2004.

Access to electronic health records in primary care- a

survey of patients’ views. Med Sci Monit,

10(11):SR17-22.

Rogerson, S., 2000. Electronic Patient Records.

IMIS, 10(5).

Tracyl, S., Dantas, C., Upshur, R., 2004. Feasibility of a

patient decision aid regarding disclosure of personal

health information: qualitative evaluation of the Health

Care. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making.

WHO SHOULD ACCESS ELECTRONIC PATIENT RECORDS

185