WE-INTENTION TO USE INSTANT MESSAGING FOR

COLLABORATIVE WORK: THE MODERATING EFFECT OF

EXPERIENCE

Aaron X. L. Shen

Department of Information Systems, University of Science and Technology of China

City University of Hong Kong Joint Advanced Research Center, SIP, Suzhou, P. R. China

Christy M. K. Cheung

Department of Finance and Decision Sciences, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong

Matthew K. O. Lee

Department of Information Systems, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

WeiPing Wang

Department of Information Systems, University of Science and Technology of China

City University of Hong Kong Joint Advanced Research Center, SIP, Suzhou, P. R. China

Keywords: We-Intention, Social Influence, Group Norm, Social Id

entity, Desire, Experience, Instant Messaging,

Computer-supported Cooperative Work.

Abstract: In response to an increase in both team collaboration

and real-time dynamics in the current business

environment, more and more companies adopt instant messaging as a means of improving team

effectiveness and efficacy and reducing delays in decision making. This study offers a novel exploration of

co-workers’ we-intention to use instant messaging for collaborative work by investigating two group-level

determinants – group norm and social identity – and considering the mediating effect of desire. A survey

(n=482) was conducted to test the differences between high and low experience respondents. The research

model explains 57.5% of the variance in we-intention. Research results show that desire partially mediates

the effects of group norm and social identity on we-intention. The relationships between group norm and

desire, as well as between group norm and we-intention, are found to be stronger for low experience group,

in contrast, the relationships between social identity and desire, as well as between social identity and we-

intention, are found to be stronger for high experience group. Implications of this study are provided for

both researchers and practitioners.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the past two decades of Information Systems (IS)

research, studies on technology adoption and use

primarily focused on individual intention (I-

intention), implying a personal intention to adopt a

new technology. Several aspects (i.e., perceived

usefulness, perceived ease of use, attitude, subjective

norm, etc.) are studied as important antecedents of

users’ individual intention (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Although prior intention-based studies have

contributed to understanding users’ technology

usage behavior, some critical gaps remain.

First, the traditional concept of individual

in

tention (I-intention) has been proven successful in

explaining technology usage behavior (Venkatesh et

al., 2003), however, it is not appropriate to explain

social act, such as collective use of collaborative

business systems. In this regard, “we-intention”,

implying an implicit or explicit agreement between

the participants to engage in a joint action (Tuomela,

235

X. L. Shen A., M. K. Cheung C., K. O. Lee M. and Wang W. (2007).

WE-INTENTION TO USE INSTANT MESSAGING FOR COLLABORATIVE WORK: THE MODERATING EFFECT OF EXPERIENCE.

In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on e-Business, pages 235-242

DOI: 10.5220/0002108802350242

Copyright

c

SciTePress

1995), is an applicable but relatively unexplored

issue in the IS discipline.

Second, prior studies defined social influence as

the degree to which an individual perceives that

significant others think he or she should use the new

systems and found that social influence constructs

are only significant in mandatory contexts

(Venkatesh et al., 2003). Gaps in our understanding

of voluntary systems usage behavior appeal for more

attention on social influence from other alterative

perspectives (Malhotra & Galletta, 2005).

Third, some criticism have pointed out that

attitude, subjective norm, and other commonly

specified direct determinants of intention provide

reasons for acting but do not incorporate the

motivational content needed to induce an intention

to do so (Bagozzi, 1992). Thus, it is important to

incorporate motivational variables, such as desire,

into intention-based model to explain how decisions

about the use of information technology become

stimulated and energized.

This study attempts to fill these gaps in the

literature by proposing and testing a social influence

model on the use of instant messaging for work-

related activities. As one of the fastest growing

Internet-based collaborative technologies, instant

messaging has been widely used in the workplace. A

recent survey showed that 35% of employees are

now using instant messaging at work (American

Management Association & The ePolicy Institute,

2006). Additionally, it is predicted that almost 99%

of organizations in North America will employ

instant messaging as one of their basic collaborative

systems by 2009 (Osterman Research, 2006). Based

on these insights, it is very important to understand

why co-workers adopt and use instant messaging for

collaborative work.

The objective of this study is to investigate

users’ we-intention to use instant messaging in task-

oriented groups. Drawing from philosophical writing

on collective intentionality and Kelman’s (1974)

social influence framework, the proposed model

investigates the roles of two important social

influence processes – internalization and

identification – in affecting we-intention to use

instant messaging for collaborative work, and further

examines the mediating effect of desire and the

moderating effect of users’ experience. In the next

section, the theoretical background of the study is

presented. The research model and its corresponding

research hypotheses are provided in section 3. The

research method and the results are reported in

sections 4 and 5 respectively. This paper concludes

with the implications for theory and practice.

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

The theoretical foundation for the present study is

reviewed in this section. Specifically, the concept of

we-intention, desire, social influence framework and

usage experience are discussed.

2.1 We-Intention

We-intention can be considered as the intention to

participate in a group to perform a group behavior in

which the participants perceive themselves as

members of the group (Bagozzi, 2000). Different

from the I-intention to perform an individual act

where other persons are not involved as essential

parts of the behavior, we-intention highlights the

individual commitment in collectivity and the social

nature of a group action. With a we-intention to

perform a group act, an individual views a group

activity holistically, in such a way that he or she sees

himself or herself as part of a social representation,

and it is the group that acts or experiences an event.

In the past two decades of IS research, intention-

based models have been dominated by the I-

intention approach to predict IS acceptance and

usage behavior (Ajzen, 1985; Davis, 1989; Fishbein

& Ajzen, 1975). However, the traditional I-intention

approach fails to capture the collective nature

involved in information technology acceptance and

usage, especially the use of collaborative systems. In

this sense, “we-intention” appears more appropriate

in studying the issues concerning group acceptance

behavior in IS research.

2.2 Desire

Desire represents a motivational state needed to

induce an intention to act and transforms the reasons

for acting into a motivation to do so (Perugini &

Conner, 2000). Bagozzi (1992) proposed that desire

mediates the effects of attitude to act, subjective

norm and perceived behavioral control on intention.

In the IS domain, previous research studies also have

adopted motivational theory to understand

technology adoption and usage behavior (e.g., Davis

et al., 1992; Venkatesh & Speier, 1999). They found

that the both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations are

consistently significant in predicting behavioral

intention across time and in both mandatory and

voluntary contexts (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

236

2.3 Social Influence Framework

Davis et al. (1989) emphasized the role of social

influences in information technology acceptance and

usage behavior and suggested that Kelman’s (1974)

theoretical distinction of social influence processes

can be considered as a theoretical base for

developing knowledge in this area. Kelman (1974)

distinguished three different processes of social

influences, including compliance, identification, and

internalization. Compliance occurs when an

individual accepts the influence to get support or

approval from significant others. It is usually

represented through the effect of subjective norm.

Identification occurs when an individual accepts the

influence to establish and maintain a self-defining

relationship to another person or group.

Internalization occurs when an individual accepts

the influence because the similarity of one’s goals

and values with that of other group members.

Prior IS research concentrated primarily on the

influence of social normative compliance (Davis et

al., 1989; Venkatesh et al., 2003) and found that the

effect of social influence is only significant under

conditions of mandatory use and with limited

experience (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Not until

recently, IS researchers started to investigate

affective commitment – that is, internalization and

identification based on personal norms – in

volitional systems adoption and usage behavior

(Malhotra & Galletta, 2005).

2.4 Usage Experience

Experience is the knowledge and skills regarding an

object or an event obtained from the involvement or

the exposure to that object or event. There is a board

range of research studying the moderating effect of

usage experience in information technology

acceptance and usage behavior (Thompson et al.,

1994; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000; Venkatesh et al.,

2003). For example, Thompson et al. (1994)

examined the direct, indirect and moderating effects

of experience on the relationships between the

attitude/belief components and utilization and found

that the moderating influence of experience was

generally quite strong. Furthermore, Venkatesh and

Davis (2000) recently found that the effect of

compliance and internalization attenuated with

increased experience.

3 RESEARCH MODEL AND

HYPOTHESES

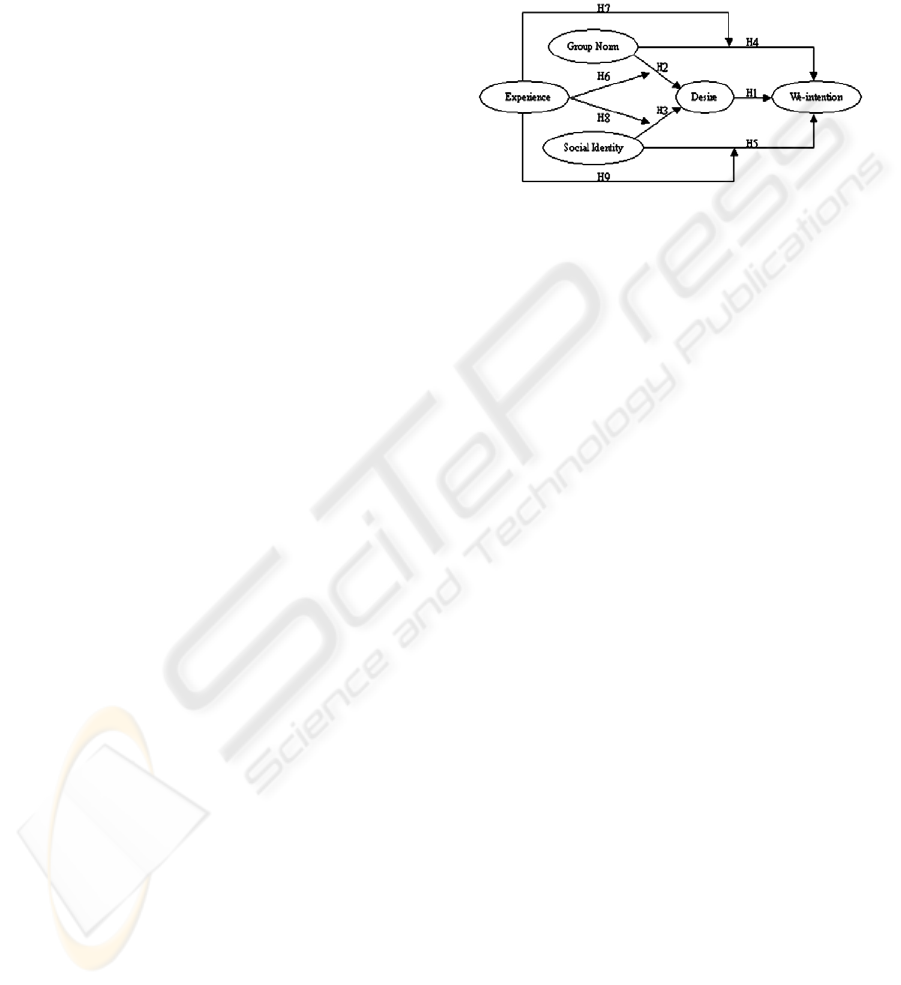

A social influence model, as shown in Figure 1, is

proposed. The constructs and their relationships are

discussed in this section.

Figure 1: The research model.

3.1 The Mediating Effect of Desire on

the Relationships between Social

Influences and We-Intention

According to previous works (Bagozzi, 1992;

Bagozzi & Dholakia, 2002; Dholakia et al., 2004;

Perugini & Bagozzi, 2001; Perugini & Conner,

2000), desire transforms the reasons to act into an

overall motivation to do so and is hypothesized as

the most proximal determinants of intention.

Following the same vein, once a person is aware of

and accepts his or her desire to use instant

messaging for collaborative work, this will motivate

him or her to form a we-intention to act. Therefore,

H1: Desire has a positive impact on we-intention to

use instant messaging for collaborative work.

Considering the voluntary use of instant

messaging for collaborative work, compliance has

not been included in our research model. Instead,

internalization and identification stemmed from

Kelman’s (1974) social influence framework are

regarded as two important determinants of instant

messaging usage behavior. Such a two-factor view

of social influence is also consistent with prior

studies (e.g., Dholakia et al., 2004).

Internalization is represented in this study

through the effect of group norm (Bagozzi & Lee,

2002). The social influence underlying group norm

is captured by the congruence of one’s values and

goals with that of other group members. In the

current study, people who are willing to use instant

messaging for collaboration share a common task. In

this regard, group norm provides the potential for

using instant messaging to collaborate with others,

however, it does not include the motivation to do so.

In accordance with previous works (Bagozzi, 1992;

WE-INTENTION TO USE INSTANT MESSAGING FOR COLLABORATIVE WORK: THE MODERATING EFFECT

OF EXPERIENCE

237

Perugini & Conner, 2000), the transformation of

group norm into we-intention to use instant

messaging for collaborative work is believed to be

provided by users’ desire to use. Based on the

discussion above, it is anticipated that desire

mediates the effect of group norm on we-intention.

H2: Group norm has a positive impact on desire to

use instant messaging for collaborative work.

Identification is characterized by social identity

in this study, which refers to one’s conception of self

in terms of the relationship with a focal group

(Bagozzi & Lee, 2002). Instant messaging provides

an easy and direct manner for group members to

establish or maintain a satisfying relationship with

another person or group. For example, the presence

awareness feature of instant messaging promotes a

sense of connectiveness among group members and

increases the attachment with the group. In this

regard, social identity, mediated by desire in the

same way as group norm, impacts users’ we-

intention to use instant messaging (Bagozzi &

Dholakia, 2002; Dholakia et al., 2004). Thus,

H3: Social identity has a positive impact on desire to

use instant messaging for collaborative work.

3.2 The Direct Effects of Social

Influences on We-Intention

Although desire mediates the effects of social

influences on we-intention to use instant messaging

for collaborative work, the mediating effects are

partial. This is because the formation of we-intention

involves both deliberative and evocative mental

processes (Dulany, 1997). Deliberative mental

processes refer to the thinking processes involving

reflection and evaluation. This process is consistent

to Frankfurt’s (1988) proposition that decision

makers give self-reflective consideration to their

desire and accept it as motivating reasons to act. In

contrast, evocative mental processes are those that

automatically and directly associate and activate

mental states. To meet other group members with

congruent values and to maintain satisfying

relationships with them, users may form a we-

intention to use instant messaging for collaborative

work automatically. Under the evocative mental

processes, group norm and social identity exhibit

direct impacts on we-intention. Therefore,

H4: Group norm has a positive impact on we-

intention to use instant messaging for collaborative

work.

H5: Social identity has a positive impact on we-

intention to use instant messaging for collaborative

work.

3.3 The Moderating Effect of

Experience

The moderating effect of experience has been

investigated in a wide range of behaviors (Davis et

al., 1989; Thompson et al., 1994; Venkatesh et al.,

2003; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). These studies

found that social normative compliance became less

important with increasing experience. Extending this

line of research, the moderating effects of

experience in internalization and identification

processes are investigated in the current study.

Prior to or at the beginning of the use of instant

messaging for collaboration, users’ knowledge and

beliefs about instant messaging are vague. They may

rely more on the opinions of others – here, the group

members with congruent values and goals – as a

basis of their usage behavior. After a period of use,

their direct experience furnish concrete information

about the use of instant messaging for collaborative

work, supplanting reliance on social cues as a basis

of decision. Thus, the influence of group norm

attenuates after users possess direct experience on

the strengths and weakness of instant messaging.

Based on the discussion above,

H6: The positive impact of group norm on desire to

use instant messaging for collaborative work is

stronger for low experience users than for high

experience users.

H7: The positive impact of group norm on we-

intention to use instant messaging for collaborative

work is stronger for low experience users than for

high experience users.

With increased experience, users of instant

messaging may have closer and stable relationships

with other group members than novice. The high

experience users also have a strong attachment and

belongingness toward the focal group. In addition,

after a long term of using instant messaging for

collaboration, the value connotation attached to this

group membership is more apparent. A deep

awareness of membership in the collaborative group

and a sustained satisfying relationship with other

group members stimulate members’ use of instant

messaging for collaborative work. Therefore,

H8: The positive impact of social identity on desire

to use instant messaging for collaborative work is

stronger for high experience users than for low

experience users.

H9: The positive impact of social identity on we-

intention to use instant messaging for collaborative

work is stronger for high experience users than for

low experience users.

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

238

4 RESEARCH METHOD

To mitigate the coverage errors or other biases

resulting from data collection method, data was

collected using both pen-and-paper survey and an

online survey. Participation in this study was

voluntary yet motivated by a lucky draw among

successful respondents. All the measures had been

validated in prior studies (see Table 1). Minor

changes in the wordings were made so as to fit them

into the current investigation context of instant

messaging. Experience was measured by a single

ordinal scale question that assessed the frequency of

using instant messaging for collaborative work in

the previous year (from 1=never to 7=always). In

addition, a screening question was employed to

identify respondents who use instant messaging for

collaborative work. Backward translation was used

to ensure consistency between the Chinese and the

original English version of the questionnaire. For the

pen-and-paper survey, a group of business students

in a local university in mainland China were invited

to participate in. A total of 301 usable questionnaires

were collected in this phase and a total of 181 usable

questionnaires were collected through online survey.

Analysis of the two samples revealed no significant

difference in the composition of users. Among the

overall respondents, 35.1% were female and 64.9%

were male. Most of them were aged between 21 and

25 (58.9%). The average time spent on instant

messaging everyday reaches 3.43 hours.

5 RESULTS

Partial Least Squares (PLS) was used to test the

proposed research model. The PLS procedure

(Wold, 1989) is a second-generation multivariate

technique which has the ability to model latent

constructs under conditions of non-normality.

Following the two-step analytical procedures (Hair

et al., 1998), the measurement model was examined

and then the structural model was assessed.

Table 1: Summary of psychometric properties of the measures.

Construct List of items Loading Source

Group Norm

(GN)

α=0.898

β=0.814

Using instant messaging for collaboration sometime within the next 2 weeks

can be considered to be a goal. For each of the members in your group, please

estimate the strength to which each holds the goal. (seven-point “weak-strong”

scale)

GN1: Strength of self’s goal.

GN2: Average of the strength of group members’ goal.

0.908

0.897

Bagozzi

& Lee,

2002

Social

Identity (SI)

α=0.908

β=0.623

SI1: How would you express the degree of overlapping between your own

personal identity and the identity of the group you collaborate with through

instant messaging when you are actually part of the group and engaging in

group activities? (eight-point “far apart-complete overlap” scale)

SI2: Please indicate to what degree your self-image overlaps with the identity

of the group of partners as you perceive it. (seven-point “not at all-very much”

scale)

SI3: How attached are you to the group you collaborate with through instant

messaging? (seven-point “not at all-very much” scale)

SI4: How strong would you say your feelings of belongingness are toward the

group? (seven-point “not at all-very much” scale)

SI5: I am a valuable member of the group. (seven-point “does not describe me

at all-describes me very well” scale)

SI6: I am an important member of the group. (seven-point “does not describe

me at all-describes me very well” scale)

0.657

0.789

0.831

0.839

0.797

0.810

Bagozzi

& Lee,

2002

Desire (DE)

α=0.916

β=0.785

DE1. I desire to use instant messaging for collaboration during the next 2

weeks. (seven-point “disagree-agree” scale)

DE2. My desire for using instant messaging for collaboration during the next 2

weeks can be described as: (seven-point “no desire at all- very strong desire”

scale)

DE3. I want to use instant messaging for collaboration during the next 2

weeks. (seven-point “does not describe me at all-describe me very well” scale)

0.865

0.901

0.891

Bagozzi

&

Dholakia,

2002

We-Intention

(WE)

α=0.905

β=0.827

WE1: I intend that our group use instant messaging for collaboration together

sometime during the next two weeks. (seven-point “disagree-agree” scale)

WE2: We intend to use instant messaging for collaboration together sometime

during the next two weeks. (seven-point “disagree-agree” scale)

0.918

0.900

Bagozzi

& Lee,

2002

Note: α= composite reliability; β= average variance extracted.

WE-INTENTION TO USE INSTANT MESSAGING FOR COLLABORATIVE WORK: THE MODERATING EFFECT

OF EXPERIENCE

239

5.1 Measurement Model

Convergent validity was assessed by examining

composite reliability and average variance extracted

(Hair et al., 1998). A composite reliability of 0.70 or

above and an average variance extracted of more

than 0.50 are deemed acceptable (Fornell & Larcker,

1981). As shown in Table 1, all the measures exceed

the recommended thresholds.

Discriminant validity indicates the extent to

which a given construct differs from other

constructs. To demonstrate the adequate

discriminant validity of the constructs, the square

root of the average variance extracted for each

construct should be greater than the correlations

between that construct and all other constructs

(Fornell & Larcker, 1981). As shown in Table 2,

each measure has an adequate level of discriminant

validity.

Table 2: Correlation matrix of the constructs.

GN SI DE WE

GN

0.902

SI 0.488

0.789

DE 0.415 0.556

0.886

WE 0.443 0.524 0.738

0.909

Note:

GN=group norm, SI=social identity, DE=desire, WE=we-

intention

*The shaded numbers in the diagonal row are square roots

of average variance extracted.

5.2 Structural Model

The hypotheses of the research model were tested

with three structural equation path models. The first

model tested H1-H5 with the full sample (n=482).

The other two models tested H6-H9, the moderating

effect of experience. The full sample was divided

into two groups based on the mean value of

experience (Mean=4.89). Thus, values from 1 to 4

are categorized as low experience (n=188) and

values from 5 to 7 as high experience (n=294).

5.2.1 The Roles of Group Norm, Social

Identity and Desire in We-Intention

Formation

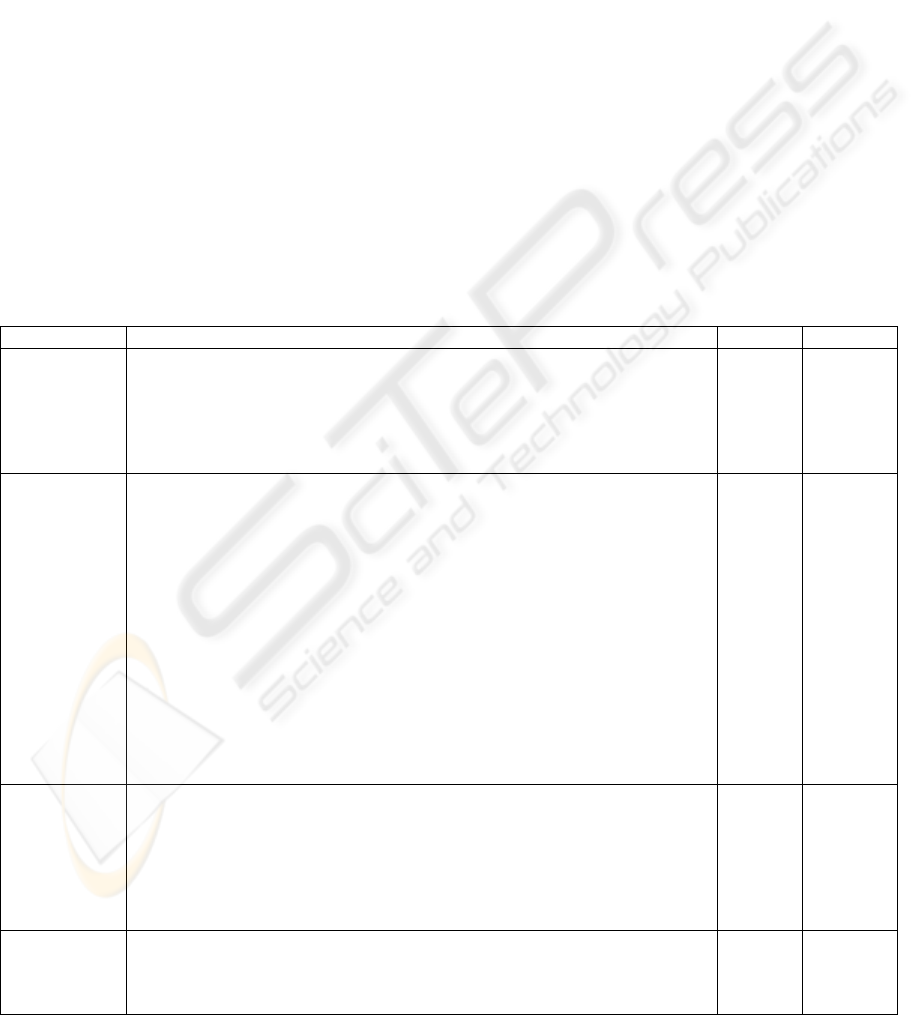

The results pertaining to H1-H5 are depicted in

Figure 2, which presents the overall explanatory

power, estimated path coefficients, and associated t-

value of the paths. Test of significance of all paths

were performed using the bootstrap resampling

procedure. All structural paths are found statistically

significant at the 0.001 level. The results show that

group norm, social identity and desire together

explain 57.5% of the variance in we-intention to use

instant messaging for collaborative work. Desire has

the strongest impact on we-intention, with a path

coefficient at 0.619, followed by group norm and

social identity, with path coefficients at 0.129 and

0.117 respectively. Desire partially mediates the

effects of group norm and social identity on we-

intention. Up to 33.6% of the variance in desire is

explained. Social identity has a stronger impact on

desire, with a path coefficient at 0.465, than group

norm, with a path coefficient at 0.188.

Figure 2: Results of research model with full sample.

5.2.2 The Moderating Effect of Experience

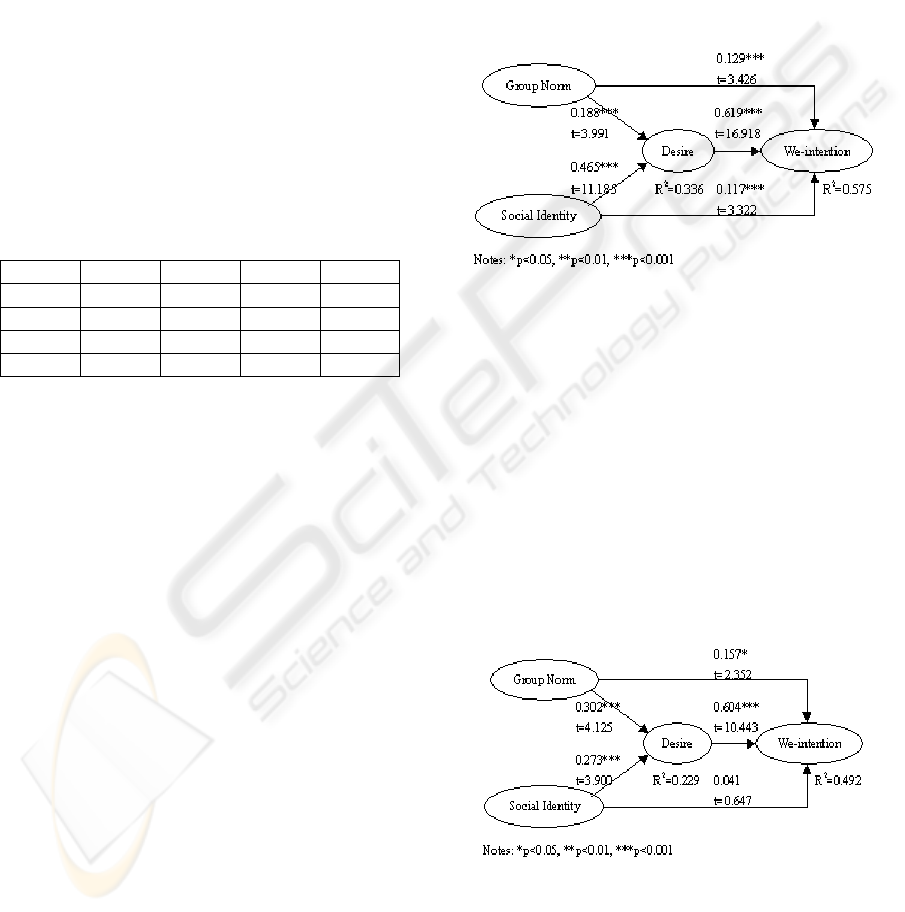

As shown in Figure 3, the structural model for low

experience group explains 49.2% of the variance in

we-intention to use instant messaging for

collaborative work and 22.9% of the variance in

desire. Desire exhibits the strongest impact on we-

intention, with a path coefficient at 0.604, followed

by group norm, with a path coefficient at 0.157.

However, social identity does not significantly

impact on we-intention. Both group norm and social

identity posit significant effects on desire, with path

coefficients at 0.302 and 0.273 respectively.

Figure 3: Structural model for the low experience group.

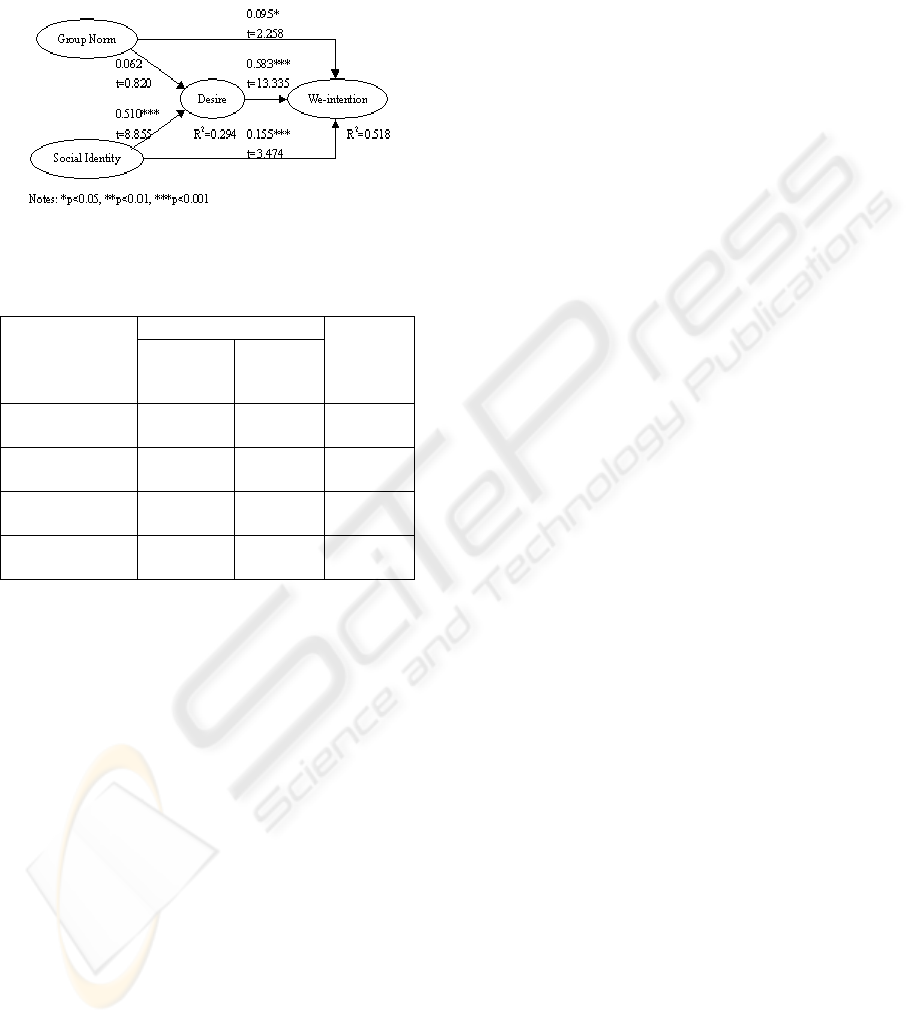

Figure 4 shows the results of the structural model for

the high experience group. The model explains

51.8% of the variance in we-intention and 29.4% of

the variance in desire. Desire posits the strongest

impact on we-intention, with a path coefficient at

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

240

0.583, followed by social identity and group norm,

with path coefficients at 0.155 and 0.095. Social

identity has a significant impact on desire, with a

path coefficient at 0.510, whereas the relationship

between group norm and desire is nonsignificant.

Figure 4: Structural model for the high experience group.

Table 3: Path comparisons between the low experience

group and the high experience group.

Path Coefficients

Path for

Comparison

Low

Experience

Group

High

Experience

Group

Result

Group Norm Æ

Desire

0.302*** 0.062 H6 is

supported

Group Norm Æ

We-intention

0.157* 0.095* H7 is

supported

Social Identity Æ

Desire

0.273*** 0.510*** H8 is

supported

Social Identity Æ

We-intention

0.041 0.155*** H9 is

supported

Note: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Table 3 summarizes the comparisons of the path

coefficients between the high and the low experience

groups. The results show that the influences of

group norm on desire and on we-intention to use

instant messaging for collaborative work were

stronger for low experience users, providing support

to H6 and H7. In contrast, the influences of social

identity on desire and on we-intention were stronger

for high experience users, providing support to H8

and H9.

6 DISCUSSION

This research investigated both direct and indirect

effects of internalization and identification processes

on “we-intention” to use instant messaging for

collaborative work. This study also found that there

are significant differences between low and high

experience users in terms of social influence

acceptance. Implications of this study are

noteworthy for both researchers and practitioners.

6.1 Implications for Researchers

This study is one of the first few attempts to

investigate “we-intention” in the acceptance and use

of collaborative technologies, in particular, instant

messaging in the current study. As mentioned

before, this study intends to fill several critical gaps

in the literature. First, the “we-intention” concept is

introduced into IS adoption and diffusion research.

Different from the traditional individual intention,

“we-intention” reflects the intention to accept and

use a particular information technology in concert

with other group members. In view of the group

notion involved, this concept is especially important

for collaborative business systems research. Second,

results of this study indicate that both internalization

and identification processes play important roles in

voluntary systems usage behavior. Third, this study

also investigates the mediating effect of desire on

the relationship between social influence and we-

intention. The results demonstrated that desire has

the strongest impact on we-intention and partially

mediate the effects of reasoned antecedents on we-

intention. Fourth, another interesting finding of the

present study reveals that experience, on the one

hand, weakens the relationship between group norm

and desire, as well as the relationship between group

norm and we-intention to use instant messaging for

collaborative work. On the other hand, experience

strengthens the relationship between social identity

and desire, as well as the relationship between social

identity and we-intention.

6.2 Implications for Practitioners

This issue is practically important as well because

the use of instant messaging in the workplace

continues to grow at a steady space. According to

the findings of this study, both group norm and

social identity play important roles in determining

we-intention to accept and use instant messaging for

collaborative work. Therefore, practitioners should

encourage users to make good use of some special

features of instant messaging, like user profile, chat

room and presence awareness, to promote the group

values and norms to all members and enhance the

awareness of group membership. Experience also

has been identified as a potential moderator of social

influence acceptance. Practitioners should wisely

differentiate between the two groups. For low

experience users, group norm is more important.

Special features of instant messaging, like user

profile and conversation history, will help to convey

values and goals of the collaborative group to the

WE-INTENTION TO USE INSTANT MESSAGING FOR COLLABORATIVE WORK: THE MODERATING EFFECT

OF EXPERIENCE

241

newcomers. In contrast, social identity plays a more

important role for high experience group. In this

regard, features, such as chat room and presence

awareness, will help to establish and maintain good

relationships among all group members.

In summary, this study provides new insights in

understanding the effects of internalization and

identification processes on desire and we-intention.

This study also investigates the moderating effect of

experience. Future research should continue to

enrich this line of research by extending the

investigation in other collaborative business

systems, especially social computing technologies.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I., 1985. From intentions to actions: A theory of

planned behavior. In Kuhl, J., & Bechmann, J., (eds.),

Action-control: from cognition to behavior, Springer,

Heidelberg, 11-39.

American Management Association (AMA) and The

ePolicy Institute., 2006. 2006 workplace e-Mail,

instant messaging & blog survey.

Bagozzi, R. P., 1992. The self-regulation of attitudes,

intentions and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly,

55, 178-204.

Bagozzi, R. P., 2000. On the concept of intentional social

action in consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer

Research, 27, 388-396.

Bagozzi, R. P., Dholakia, U. M., 2002. Intentional social

action in virtual communities. Journal of Interactive

Marketing, 16, 2-21.

Bagozzi, R. P., Lee, K. H., 2002. Multiple routes for social

influence: The role of compliance, internalization, and

social identity. Social Psychology Quarterly, 65, 226-

247.

Davis, F. D., 1989. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of

use, and user acceptance of information technology.

MIS Quarterly, 13, 319-340.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., Warshaw, P. R., 1989. User

acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of

two theoretical models. Management Science, 35, 982-

1003.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., Warshaw, P. R., 1992.

Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in

the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,

22, 1111-1132.

Dholakia, U. M., Bagozzi, R. P., Pearo, L. K., 2004. A

social influence model of consumer participation in

network- and small-group-based virtual communities.

International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21,

241-263.

Dulany, D. E., 1997. Consciousness in the explicit

(deliberative) and implicit (evocative). In Cohen, J. D.,

& Schooler, J. W. (eds.), Scientific approaches to

consciousness. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

Fishbein, M., Ajzen, I., 1975. Belief, attitude, intention,

and behavior: An introduction to theory and research.

Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, MA.

Fornell, C., Larcker, D., 1981. Evaluating structural

equation models with unobservable variable and

measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18,

39-50.

Frankfurt, H., 1988. The importance of what we care

about. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., Black, W. C.,

1998. Multivariate data analysis. Prentice-Hall, Upper

Saddle River, NJ.

Kelman, H. C., 1974. Further thoughts on the processes of

compliance, identification, and internalization. In

Tedeschi, J. T. (ed.), Perspectives on social power,

Aldine Press, Chicago, 126-171.

Malhotra, Y., Galletta, D., 2005. A multidimensional

commitment model of volitional systems adoption and

usage behavior. Journal of Management Information

Systems, 22, 117-151.

Osterman Research., 2006. Instant messaging tough

enough for business: No server required.

Perugini, M., Bagozzi, R. P., 2001. The role of desires and

anticipated emotions in goal-directed behavior:

Broadening and deepening the theory of planned

behavior. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 79-

98.

Perugini, M., Conner, M., 2000. Predicting and

understanding behavioral volitions: The interplay

between goals and behaviors. European Journal of

Social Psychology, 30, 705-731.

Thompson, R., Higgins, C. A., Howell, J. M., 1994.

Influence of experience on personal computer

utilization: Testing a conceptual model. Journal of

Management Information Systems, 11, 167-187.

Tuomela, R., 1995. The importance of us: A philosophical

study of basic social notions. Stanford University

Press, Stanford, CA.

Venkatesh, V., Davis, F. D., 2000. A theoretical extension

of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal

field studies. Management Science, 46, 186-204.

Venkatesh, V., Speier, C., 1999. Computer technology

training in the workplace: A longitudinal investigation

of the effect of the mood. Organization Behavior and

Human Decision Processes, 79, 1-28.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., Davis, F. D.,

2003. User acceptance of information technology:

Toward a unified view, MIS Quarterly, 27, 425-478.

Wold, H., 1989. Introduction to the second generation of

multivariate analysis. In Wold, H. (ed.), Theoretical

empiricism: A general rationale for scientific model-

building, Paragon House, New York, USA.

ICE-B 2007 - International Conference on e-Business

242