PARADIGM SHIFT IN INTER-ORGANISATIONAL

COLLABORATION

A Framework for Web based Dynamic eCollaboration

Ioakim (Makis) Marmaridis and Athula Ginige

AeIMS Research Group, University of Western Sydney, Sydney, Australia

Keywords:

Dynamic eCollaboration, World Wide Web, Collaboration Paradigm Shift, Bitlet, Workflow Engine, P2P.

Abstract:

The proliferation of the World Wide Web (web) offers new ways for organisations to do business and collabo-

rate with others to gain competitive advantage. Dynamic eCollaboration has the characteristics to keep up with

the fast changing business landscape. It requires however a framework for collaboration that can also keep

up with rapid change. In this paper we present the Dynamic eCollaboration model that brings the concepts

of P2P collaboration to organisations. It fills this gap and offers a new avenue for organisations of all sizes

to embrace collaboration and benefit from it. We also present our technology framework built to support Dy-

namic eCollaboration. The framework is component-based and extensible with an architecture that can scale.

It incorporates a flexible security subsystem, a lightweight workflow engine optimised for web applications

and a novel method for bundling and sharing web based information called Bitlet.

1 INTRODUCTION

Business collaboration as a means to gaining compet-

itive advantage is well established (Lee, 2004) and the

area of collaboration in general receives a lot of atten-

tion from researchers. From collaboration between

individuals (Cap, 2003; David et al., 2005; Scott et al.,

1997) to group collaboration (Mandviwalla and Olf-

man, 1994; Dus, 2004; Sun, 2003; Thomas, 1997;

Mark et al., 1996) and collaboration for enterprises

making their resources accessible to select partners

and business associates (Cha, 2004; Sybase, ; Aissi

and Chan, 2003; Donnan, 2002) a lot of systems have

been developed to support it. Some have started off

as research platforms (Arb, 2002; Egi, 2004) subse-

quently either turning commercial or remaining free

and open source and others, particularly targeting en-

terprise collaboration, come from very well known

vendors. Oracle (:20, 2003), Novell (Novell, ), IBM

and Microsoft are just few of the large vendors that

have delved into providing solutions for collabora-

tion of some form. While the quality and feature

set of these solutions vary greatly, some of these of-

fer a host of features and abilities to the organisa-

tions who can put them in place. Although the col-

laboration space is full with solutions for most types

of collaboration, the authors have observed the lack

of viable solutions for electronic collaboration be-

tween small and medium organisations (SMEs) al-

though they could benefit greatly from adopting those.

The reason is that all existing business collabora-

tion solutions follow the same paradigm that does not

work well in the SME space. The authors advocate a

paradigm shift in the way inter-organisational collab-

oration happens. We strongly believe that Dynamic

eCollaboration (Marmaridis et al., 2004) that models

this new paradigm can offer tangible benefits to SMEs

and other larger organisations. We also firmly be-

lieve that Dynamic eCollaboration can be practically

facilitated via a web-based framework. This paper

presents the new paradigm the authors advocate for

inter-organisational collaboration and the framework

that can support it.

178

(Makis) Marmaridis I. and Ginige A. (2007).

PARADIGM SHIFT IN INTER-ORGANISATIONAL COLLABORATION - A Framework for Web based Dynamic eCollaboration.

In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Software and Data Technologies - Volume ISDM/WsEHST/DC, pages 178-185

DOI: 10.5220/0001335501780185

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 MOTIVATION FOR THIS

WORK

We have been researching electronic collaboration

for over four years aiming to understand why SMEs

are not adopting electronic collaboration using the

web. In the wider context look we look for the op-

timum way to perform and facilitate web based inter-

organisational collaboration. We view the web as a

mature platform for cheap, secure communication and

therefore an enabler for collaboration (Marmaridis

et al., 2004). During this time we have surveyed the

landscape of collaboration tools and methods from in-

ter personal to enterprise-level collaboration. There

are many tools from many vendors, some represent-

ing excellent use of technology with impressive fea-

ture sets however they still all fail to appeal to the

SMEs, who hold the middle ground in the collabora-

tion landscape. We therefore started looking beyond

technology solutions and saw that a paradigm shift is

necessary in the way collaboration takes place. There

must be more choice offered to individuals within

an organisation when it comes to collaborating, and

at the same time organisations must know they have

control over the information they share with others.

A policy-driven, completely top down approach leads

to micro-management and does not work in the long-

run, on the other hand a bottom-up approach that al-

lows individuals to freely share information without

maintaining control does not work either. Through

interacting with SMEs that wish to collaborate we de-

rived the desirable characteristics of such an engage-

ment and we also took into account the particular cir-

cumstances of SMEs that include lack of IT expertise

and lack of large infrastructure investment for col-

laboration. A detailed analysis of these characteris-

tics in the context of SMEs can be found in some of

our previous work (Marmaridis and Unhelkar, 2005).

To fulfil these requirements we therefore derived an

evolved model of electronic collaboration called Dy-

namic eCollaboration (Marmaridis et al., 2004). We

define Dynamic eCollaboration as flexible, electronic

collaboration based on short to medium term projects

where business partners have ephimeral relationships

and are able to opt-in and out from each project at

any time. Wishing to see Dynamic eCollaboration be

adopted in the real world, we went on to design the

key infrastructure components necessary to support

the nearly ad-hoc, dynamic nature of collaboration.

This paper presents this framework in detail because

we believe that Dynamic eCollaboration and its as-

sociated paradigm shift has many benefits to offer to

organisations of all sizes not only SMEs.

3 CONTEMPORARY

COLLABORATION

PARADIGMS

There are three major types of collaboration one

can find via academic literature or by observation

amongst people and organisations. Collaboration

between individuals on one to one basis, group

based collaboration and enterprise-level collabora-

tion. These three types differ significantly in the fol-

lowing aspects:

Trust Different trust levels are necessary to establish

and maintain each type of collaboration. Individ-

uals require little trust up front, groups more and

enterprises the most.

Risk Inter-personal collaboration has the least which

explains why instant messaging networks are in

such high use. Group collaboration involves more

risk as it requires more commitment and resources

to setup and get going in the first place. Enteprise-

level collaboration has the most amount of per-

ceived risk as decision-making may be critical de-

pending on the type of collaboration.

Amount of information exposure Similarly to the

previous factors, individuals in an IRC channel

can disguise their own identity rather effectively,

in groups it is harder to do so and also more in-

formation is exchanged. Finally at the enterprise

level company secrets may be disclosed by acci-

dent or otherwise and information may be very

damaging if it reaches competitors by any chance.

Amount of control Individuals are content with be-

ing able to interrupt the communication as soon

as they like. They can stop responding to emails

or instant messages, they can remove a web

page with information that they have put online.

Groups have little control over what is shared, by

whom and for what purpose, this is sometimes ad-

vantageous and other times it is not. Organisa-

tions feel the need to exercise a lot of control be-

cause of the critical nature of some collaborations

and the sensitivity of the information exchanged.

Collaboration Direction Bottom-up for individuals

and groups, with people taking initiative to con-

tribute or not, comment and provide feedback or

otherwise. Top-down, policy driven, with steps

to police access, and log activities, these are the

characteristics of enterprise-level collaboration.

In inter-personal and group collaboration every-

one participating is able to contribute equally and to

a large extent they are expected to. In enterprise-

collaboration, participants are typically in two groups,

PARADIGM SHIFT IN INTER-ORGANISATIONAL COLLABORATION - A Framework for Web based Dynamic

eCollaboration

179

internal staff and external partners or associates. Staff

are the people who put up information and contribute

the bulk of it with external partners mostly consuming

information and contributing either simple documents

or comments and ideas. This is justified since giving

partners access to internal systems via an extranet can

be a very complex undertaking in order to safeguard

security giving rise to issues of identity management,

single sign-on, policy based access control to differ-

ent internal applications and still involving large risk

in letting outsiders access your own internal systems.

In inter-personal and group collaboration on the other

hand, there is usually no need for cross-authentication

or identity management, as this is a bottom-up ap-

proach.

3.1 Problems with Contemporary

Collaboration Paradigms

For business collaboration a bottom-up approach is

too informal, it does not offer any guarantees that in-

formation leaks can be detected and contained in a

timely manner. On the other hand, the top-down ap-

proach may be workable to an extent for large en-

terprises when they deal with a few well established

business partners and where an army of IT experts is

available to configure and maintain “enterprise grade”

collaboration systems. Everyone else in between in-

cluding SMEs is not really catered for by these two

ways of performing electronic collaboration. SMEs

for instance require some level of inter-organisational

trust to be in place before they engage in collabora-

tion, on the other hand they cannot afford the top-

down rigour enterprises try to exercise due to cost

and time constraints. On the other hand, they need

the flexibility of letting their staff take decisions about

what is shared in the context of each collaboration and

also allow their partners an equal footing to also share

just as freely their own resources. Finally, they can

benefit greatly by allowing access to web applications

they are running internally and at the same time they

cannot afford the price and complexity of systems that

can give them federated identity management and sin-

gle sign-on like enterprises use and battle with.

4 THE NEW AND EMERGING

PARADIGM OF DYNAMIC

ECOLLABORATION

The requirements SMEs and other organisations have

from eCollaboration are not catered for by the current

paradigm enterprises use to share some of their re-

sources with others. When you think about it it is al-

most as if SMEs are like individuals in the amount of

flexibility they require. Yet again they want to main-

tain some high level of control over the entire process

that can in turn mitigate the risk of critical informa-

tion being exposed.

This is where the paradigm shift is necessary to al-

low the flexibility and ad-hoc nature of inter personal

collaboration in a business setting. Dynamic eCollab-

oration can give rise to this paradigm by working at

three levels. Firstly, it sets up a context for the over-

all collaboration between two or more organisations

requiring them to reach an in-principal agreement to

collaborate. Secondly, it maps each actual engage-

ment into a project that is used to keep related ac-

tivities together and also simplify the interactions for

staff that is involved in each project. Finally, in the

context of a project it allows freedom to the members

of the project team to contribute and share resources

and interact with one another. The degree of freedom

is configurable on a per-project basis and although

high by default it can be turned down as needed. Also

all the information shared is trackable and sharing can

be revoked at any time at the project or the whole or-

ganisation level.

Figure 1 below shows graphically how Dynamic

eCollaboration would be represented on the same

landscape as the other types, inter-personal, group and

enterprise-level collaboration.

People-Driven

Company-Driven

Only staff can contribute resources

(partner interaction is limited)

Everyone can contribute

resources

Inter-personal

Collaboration

Dynamic

eCollaboration

Enterprise-level

Collaboration

Figure 1: Dynamic eCollaboration in the Landscape.

Dynamic eCollaboration fits in-between the other

two approaches and allows everyone in a project to

contribute resources while at the same time activities

are user driven (in the context of overall approval by

the business owners of the respective organisations).

Dynamic eCollaboration is able to do this by intro-

ducing a number of key concepts as follows: An up-

front inter-organisational agreement mapping the ini-

tial trust between each partner and providing an um-

brella for each collaborative project. Mapping of col-

laborative activities into projects in order to reduce

complexity and provide better management overall.

ICSOFT 2007 - International Conference on Software and Data Technologies

180

The introduction of Virtual Teams that work on each

project and whose members come from all collabo-

rating partners and have the ability to contribute and

use available resources. A novel mechanism for shar-

ing web accessible resources including applications

in a controlled and flexible way. Finally, a method for

sharing business processes between partners via map-

ping them onto executable workflow definitions.

5 THE DYNAMIC

ECOLLABORATION

CONCEPTUAL MODEL

At its core, Dynamic eCollaboration involves staff

members from one or more organisations working

together and sharing information and business pro-

cesses. The information sharing may take place via

a given application or through a series of applications

and document exchanges. Likewise, the business pro-

cess sharing may follow a prescribed format, it may

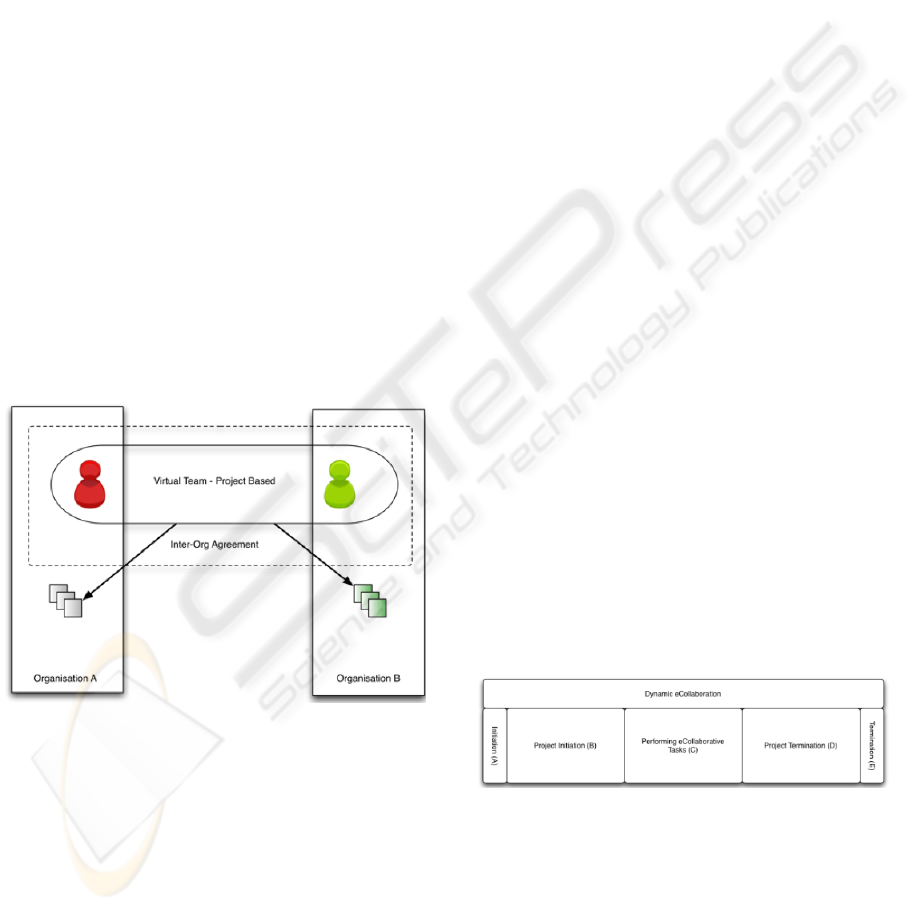

be semi-structure or completely ad-hoc. Figure 2 vi-

sualises Dynamic eCollaboration in action. We will

use this figure to explain the different parts of the con-

ceptual model in detail below.

Figure 2: Conceptual Model of Dynamic eCollaboration -

Users in a Virtual Team make resources from their organi-

sations accessible.

5.1 Inter Organisational Trust in

Dynamic Ecollaboration

The model takes into account the importance of Trust

in Dynamic eCollaboration and therefore has a built-

in requirement for up front inter-organisational Trust

between the parties that will be collaborating. Be-

fore any work can take place, a once-off trust must

be established and it has to be kept current and in

place in order for other work to happen between staff

in the partner organisations. Establishing this Trust

requires that there is in-principle agreement between

key stockholders in each partner organisation that

they are willing to join forces and work with one an-

other.

This step also has two more desirable effects that

assist in Trust building and lower the perceived risks

of organisations taking part in collaboration. The two

effects are as follows:

Unanimous acceptance of new entrants required.

Where there is an established collaboration un-

derway, a new partner can only be introduced

if all others agree to establish this high level of

inter-organisational Trust with them. Effectively

this prohibits one partner from bringing in another

organisation they may feel favourably towards

without the consent of all others participants

and therefore increase the risk of information

exposure for those other partners.

All sharing depends on Inter-organisational Trust.

Trust plays a large part in the amount of col-

laboration an organisation is willing to enter to

and the degree of information sharing they are

willing to allow. Therefore, having ultimate

control over what information is shared across all

collaborative engagements allows organisations

to be less sceptical about embarking on Dynamic

eCollaboration. In more traditional forms of

collaboration there may be some upfront require-

ments for establishing who the collaborative

partners are however there is no easy way to

stop each and every interaction with a particular

business partner easily.

When it comes to entering into Dynamic eCollab-

oration the conceptual model offers a set of five steps

as shown in figure 3 that organisation can follow.

Figure 3: Dynamic eCollaboration requires inter-

organisational trust to be in place before any joint work can

take place.

If for instance there are two organisations that

wish to collaborate and they have never had a chance

to work with one another before, in step A their stake-

holders would come together and have an in-principle

agreement about collaborating. This agreement may

have some legal binding effect but more importantly

PARADIGM SHIFT IN INTER-ORGANISATIONAL COLLABORATION - A Framework for Web based Dynamic

eCollaboration

181

it must be codified in the respective platforms for col-

laboration that each organisation has access to and

is going to be using in order to participate in Dy-

namic eCollaboration. This offers blanket protection

for both organisations as a risk mitigation measure. It

is revokable by either one and should that happen, as

in step E in figure 3 any current collaborative activ-

ities will come to an immediate stop, including any

data shared.

Once the inter-organisational Trust in place, the

two organisations can start working on joint projects

that are established, managed and terminated on their

own as long as the umbrella Trust is in place. At each

step in the lifecycle of each project the following ac-

tivities take place:

Project Initiation (shown as stage B in figure 3)

During the project initiation, one of the col-

laborating parties creates a new project with a

description and makes it available to select other

parties. All then can accept to be part of the

project or not and further they can designate

which of their staff members will be part of

the Virtual Team associated with this particular

project.

Performing actual tasks (stage C in figure 3) As

the Virtual Team has been assembled for this

project, its members are now able to start sharing

resources they have access to with others in the

Virtual Team. These resources could be in the

form of applications or data - more on resource

sharing follows later in this chapter. During the

course of the collaborative project additional

collaboration support tools may be required and

used including wikis, threaded discussion forums,

instant messaging and voice chat software. The

Project and its associated Virtual Team exist

for as long as the high level inter-organisational

agreement to collaborate is in place and should

that be revoked all projects and information

sharing is then stopped.

Project Termination (stage D in figure 3) The

project will be terminated once completed or

by mutual agreement to do so earlier. The

termination of this particular project does not

have any flow-on effects onto other projects that

may be currently in progress between those same

or different organisations.

Overall, knowing that there is the ability to safely

pull out of a project or the entire collaboration at

any time is available, in my experience can act as a

catalyst for organisations interested in collaborating.

Such knowledge leads to a lower trust threshold to be

required for getting into collaborative work with other

organisations, therefore encouraging participation.

5.2 Projects in Dynamic Ecollaboration

The conceptual model of Dynamic eCollaboration de-

fines projects as the unit of management for collabo-

rative activities. Each time an organisation decides to

start on a new piece of collaborative work with others

a new project is created to accommodate this.

Therefore projects act as containers of related in-

formation for each engagement and contain refer-

ences to individual users, information about roles

these users may have, ad-hoc groups that they may

be part of in the context of this project and always

contain the Virtual Team which is a special type of

group with all the individuals assigned to the projects

as its members. Finally, a project can contain other

pieces of arbitrary data such as pointers to resources,

access control directives and workflow definitions and

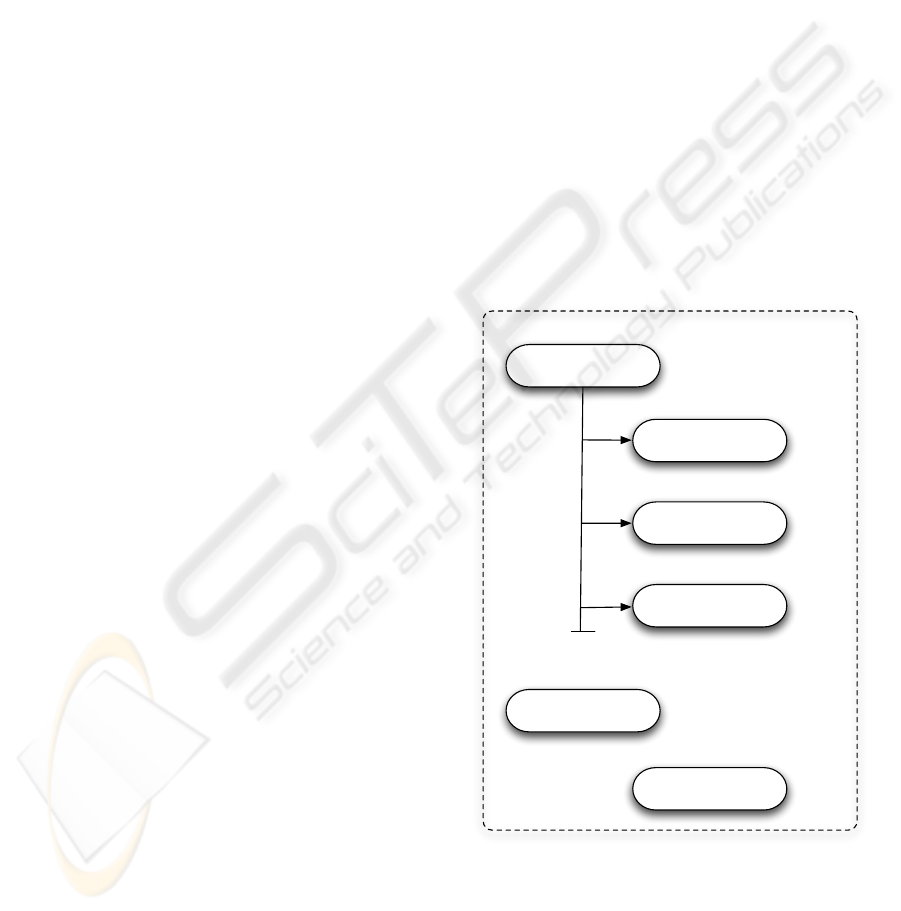

instances that map to business processes. Figure 4

shows the constituents of a typical Dynamic eCollab-

oration project.

Virtual Team

Groups

Roles

Individuals

(people)

Capabilities

Other data

(e.g. workflows)

Figure 4: In Dynamic eCollaboration each project acts as a

container for the Virtual Team and associated data.

ICSOFT 2007 - International Conference on Software and Data Technologies

182

5.2.1 The Relationship between Projects and

Applications

Many other collaborative systems such as Groove (Jr.

et al., 2002) and productivity applications already im-

plement the concept of using projects to segregate in-

formation. Unlike other systems however, projects

under Dynamic eCollaboration are not subordinate to

applications. On the contrary the conceptual model

defines projects as entities that may incorporate one or

more different applications (or parts of applications)

at the same time as resources. This single character-

istic of the conceptual model of Dynamic eCollabo-

ration offers large amounts of flexibility in real life

implementations of Dynamic eCollaboration. For in-

stance a project may be established that requires peo-

ple to share existing documents, discuss particular is-

sues using a threaded discussion forum and co-author

new documents via a wiki. The conceptual model al-

lows them to do all that by defining a single project

where each participant has a single identity that is

linked to the project. From then on, no additional

overheads are necessary in order to manage access

to the different applications or parts of those appli-

cations. And finally when the project comes to an

end and the Virtual Team is dissolved there are no

left-overs that have to be managed in the different ap-

plications individually. This behaviour of the model

enhances maintainability of each project and reduces

the time and effort required to manage it by reducing

the amount of relationships that must be established

and tracked.

Additionally, because projects can transcend ap-

plications and they can incorporate any number of re-

sources and users from one or more organisations at

the same time, they allow overlay business processes

to be set-up fast. All users within a project are ad-

dressable without any concerns of their origin.

5.3 Virtual Teams in Dynamic

Ecollaboration

The concept of a Virtual Team in Dynamic eCollab-

oration abstracts away the true location of members

and provides a single, unified, consistent view of the

people who are actually participating in each collab-

orative project. Also the Virtual Team is a key con-

struct to providing access control for the different re-

sources within each project and can simplify the ex-

pression of access control directives. If for instance a

new project requires that all of its members have ac-

cess to a given wiki page instead of granting access

rights to each individual the same can be achieved by

granting rights to the Virtual Team since by definition

it contains every person associated with the project.

Figure 5 shows a view of how people within a

project may be organised for the purposes of access

control and collaboration in general.

Virtual Team

Project

User with Role

Group of Users

Figure 5: A Typical Virtual Team in a Dynamic eCollabo-

ration Project.

By definition, each person that belongs into a

project must also be a member of the Virtual Team,

however they need not necessarily have any other

roles or group memberships. Having a role does not

exclude people from also being part of groups within

the Virtual Team. Any one person within a Virtual

Team may be member in one or more groups at the

same time and they may have one or more roles also

at the same time. In addition, a role may be given

to only one person at a time. There is no limit to

the number of users a group may contain. Role and

group names must be unique within the context of a

given project but need not be unique across projects.

By design and to limit unecessary complexity, no two

people in the same project may have the same role.

If this is desired, a group can be created instead. No

groups within groups are allowed, as it would have

raised the overall complexity of the model both con-

ceptually and at the implementation level.

Another key characteristic of Dynamic eCollabo-

ration is the speed of change in configuring projects,

teams and access control within those. It is neces-

sary that resources can be added in projects and that

they can be managed with minimum overheads. To

facilitate speed and lower overheads, business users

must be able to configure how collaborative activities

take place. The access control system in the concep-

tual model for Dynamic eCollaboration takes this into

account and provides for fast, simpler sharing by in-

corporating one more important rule. Unless speci-

fied otherwise, anyone within a project is able to con-

tribute resources provided that:

PARADIGM SHIFT IN INTER-ORGANISATIONAL COLLABORATION - A Framework for Web based Dynamic

eCollaboration

183

1. They themselves have access to this resource they

wish to contribute already.

2. They can only grant access rights for this resource

up and including their own level of access for it.

These simple rules along with the ability to seg-

ment access control by project and tie access control

directives to individual users, roles, groups or the Vir-

tual Team as a whole provide flexibility, granularity

and simplicity in managing access control in collabo-

rative projects.

5.4 Sharing of Information and

Resources

Information sharing between users is the cornerstone

of collaboration. In Dynamic eCollaboration re-

sources can be of many types including documents,

single web pages, web applications or parts thereof.

Each resource is captured as a Bitlet which is a self

standing bundle of information that can be easily

shared with others in a project. Bitlets can be static

or interactive and allow in the latter case for instance

the recipient to fill in and post back any HTML forms

that they may contain. Details about Bitlets, their de-

sign and technical implementation can be found in our

previously published work (Marmaridis and Ginige,

2006).

5.5 Sharing of Business Processes

Collaboration involves the joint work of a number of

users via information sharing that can be structured

and fully pre-specified, semi structured or completely

unstructured. Figure 6 shows the spectrum of in-

teractions that can take place within a collaboration

project.

Figure 6: Collaborative interactions classification based on

degree of structure.

In our experience actual collaborative projects in-

volve a mixture of interactions that is somewhere in

between the two extremes. In the context of Dy-

namic eCollaboration, it is not practical to try and

pre-specify each and every interaction and then rely

on a workflow engine to enact the necessary sequence

of events. On the other hand, fully ad-hoc collabo-

ration may be useful at an inter-personal level how-

ever it is not always well suited for business collab-

oration. This is mainly because ad-hoc interactions

are not typically tracked and controlled. In a business

setting having the ability to revoke previously taken

actions or recall shared resources for amendment or

just to pull them out of circulation is a desirable prop-

erty.

Unlike inter-personal collaboration, in business

collaboration it is often necessary to enact business

processes that transcend organisational boundaries.

To facilitate this, the Dynamic eCollaboration model

makes provision for a workflow engine for executing

the different business processes. Unfortunately due

to lack of space we cannot describe the design prin-

ciples behind this in any detail. However business

processes mapped to workflows operate in the context

of each project and have direct ability to setting and

changing access control capabilities for team mem-

bers of the project. This architecture allows the de-

sign, enactment and development of a variety of busi-

ness processes as needed in an evolutionary manner

that supports the flexible and nearly ad-hoc nature of

Dynamic eCollaboration. Along with the other com-

ponents of the framework supporting Dynamic eCol-

laboration we have also fully implemented the work-

flow engine and hoping to publish its details in an up-

coming conference.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper we have presented Dynamic eCollab-

oration, an evolved form of electronic collaboration

aimed at organisations of all sizes. It combines a num-

ber of key concepts around project based collabora-

tion driven by virtual teams of people coming from

different organisations to form a common working

group for a particular purpose. Backed by a novel

approach to sharing web based information in a con-

trolled and reusable manner and a lightweight mech-

anism for sharing business processes, Dynamic eCol-

laboration represents a paradigm shift in the way busi-

ness collaboration can be performed. It allows partic-

ipants from all partner organisations to equally con-

tribute resources for the use of the project team, not

just open up existing systems and resources for use

by select few in an “extranet”. It empowers individu-

ICSOFT 2007 - International Conference on Software and Data Technologies

184

als with taking the initiative to share information and

resources and work collaborative while allowing each

organisation to contain any information leaks quickly

and effectively.

We see great opportunity for improvement in the

area of resource sharing to include the ability to ag-

gregate and share again the aggregated resources.

Also we are focusing our efforts in providing bet-

ter support to business users for creating new work-

flows for their projects easily via Ajax enabled web

GUIs. Nevertheless we have implemented the tech-

nology necessary to support Dynamic eCollaboration

in practice and have integrated it with our CBEADS

framework (Ginige, 2002). We are currently putting

the technology into practical use through our work

with a group of four SME organisations that wish to

collaborate with one another.

The new paradigm for business collaboration that

Dynamic eCollaboration embraces will not only lead

to the uptake of collaboration by SMEs, we strongly

believe it will also have lasting effects in the way

larger enterprises collaborate with their partners and

associates.

REFERENCES

(2002). MoCha: a middleware based on mobile channels.

TY - CONF.

(2003). Oracle collaboration suite. Technical report.

http://otn.oracle.com/products/cs/index.html.

(2003). Towards a framework for collaborative peer groups.

TY - CONF.

(2003). Yet another framework for supporting mobile and

collaborative work. TY - CONF.

(2004). DACS: distance aware collaboration system for

face-to-face meetings. TY - CONF.

(2004). Pervasive enablement of business processes. TY -

CONF.

(2004). Web services for groupware in distributed and mo-

bile collaboration. TY - CONF.

Aissi, S. and Chan, A. (2003). Collaboration-

protocol profile and agreement specifi-

cation version 2.0. Technical report.

http://www.ebxml.org/specs/index.htm#technical reports.

David, R., Hiroko, W., Kristie, K., and Rogerio de,

P. (2005). What ideal end users teach us about

collaborative software. Number 260-263. ACM

Press, Sanibel Island, Florida, USA. 1099248

http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/1099203.1099248.

Donnan, D. (2002). Ceo/presidents’ forum - action plan

for trading partner e-collaboration. Technical report.

http://www.gmabrands.com/publications/docs/

ceoforum.pdf.

Ginige, A. (2002). Handbook of Software Engineering

and Knowledge Engineering, volume 2, chapter New

Paradigm for Developing Evolutionary Software to

Support E-Business, pages 711–725. World Scientific.

Jr., R. J. B., Agrawal, R., Gruhl, D., and Somani, A. (2002).

Youserv: a web-hosting and content sharing tool for

the masses. In WWW ’02: Proceedings of the 11th

international conference on World Wide Web, pages

345–354, New York, NY, USA. ACM Press.

Lee, M., editor (2004). Collaborating to Win - Creating an

Effective Virtual Organsiation, Taipei, Taiwan. 26-27

March 2004.

Mandviwalla, M. and Olfman, L. (1994). What do groups

need? a proposed set of generic groupware re-

quirements. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact.,

1(3):245–268.

Mark, R. C., Jay, M. T., and Jay, G. (1996). Made-

fast: collaborative engineering over the internet.

Commun. ACM, 39:78–87. 234474 0001-0782

http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/234215.234474 ACM

Press.

Marmaridis, I. and Ginige, A. (2006). Sharing informa-

tion on the web using bitlets. Proceedings of the 6th

international conference on Web engineering, pages

185–192.

Marmaridis, I., Ginige, J., and Ginige, A. (2004). Web

based architecture for dynamic ecollaborative work.

International Conference on Software Engineering

and Knowledge Engineering.

Marmaridis, I. and Unhelkar, B. (2005). Challenges in mo-

bile transformations: A requirements modeling per-

spective for small and medium enterprises. Proceed-

ings of the International Conference on Mobile Busi-

ness (ICMB’05)-Volume 00, pages 16–22.

Novell. A superior foundation for secure identity a superior

foundation for secure identity management solutions.

Scott, R., Sherif, J., and Kathy, R. (1997). Web-based col-

laborative library research. Number 152-160. ACM

Press, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States.

263808 http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/263690.263808.

Sybase. emarketlink - enabling b2b collaboration.

http://www.eshop.sybase.com/.

Thomas, R. K. (1997). Team-based access control (tmac):

a primitive for applying role-based access controls in

collaborative environments. In RBAC ’97: Proceed-

ings of the second ACM workshop on Role-based ac-

cess control, pages 13–19, New York, NY, USA. ACM

Press.

PARADIGM SHIFT IN INTER-ORGANISATIONAL COLLABORATION - A Framework for Web based Dynamic

eCollaboration

185