CONSTRUCTIVIST INSTRUCTIONAL PRINCIPLES, LEARNER

PSYCHOLOGY AND TECHNOLOGICAL ENABLERS OF

LEARNING

Erkki Patokorpi

IAMSR, Åbo Akademi University, Lemminkäinengatan 14B, 20520 Åbo, Finland

Keywords: constructivist pedagogy, ICT enhanced learning, instructional method.

Abstract: Constructivists generally assume that the central principles and objectives of the constructivist pedagogy are

realized by information and communication technology (ICT) enhanced learning. This paper critically

examines the grounds for this assumption in the light of available empirical and theoretical research

literature. The general methodological thrust comes from Alavi and Leidner (2001), who have called for

research on the interconnections of instructional method, psychological processes and technology.

Hermeneutic psychology and philosophical argumentation are applied to identify some potential or actual

weaknesses in the chain of connections between constructivist pedagogical principles, psychological

processes, supporting technologies and the actual application of ICT in a learning environment. One

example of a weak link is personalisation technologies whose immaturity hampers the constructivists’

attempts at enabling learners to create personal knowledge. Pragmatism enters the picture as a ready source

of criticism, bringing out a certain one-sidedness of the constructivist view of man and learning.

1 INTRODUCTION

As technology keeps evolving, things like mobile

learning and edutainment become more

commonplace, challenging the old pedagogical

principles and practices. Yet it is not clear how the

new ICT will (if at all) change the ways we perceive

the world around us, and how educators could or

should use the new tools? In fact, we are still

struggling to make sense of the impact of the more

traditional forms of ICT, like PCs, on learning. Kuh

and Vesper (1999) and Flowers et al. (2000) number

among the very first major empirical studies on the

cognitive effects on learning exerted by more

traditional ICT.

Constructivist pedagogy has been here singled

out for scrutiny because, in the happy phrase of

Richard Fox (2001, p. 23), constructivism is “the

uncritically accepted textbook account of learning".

In modern constructivist learning theories,

knowledge is seen essentially as a social construct.

Because the learner builds on his prior knowledge

and beliefs as well as on the knowledge and beliefs

of others, learning needs to be scrutinized in its

social, cultural and historical context (Piaget, 1982;

Vygotsky, 1969; Leontjev, 1977). According to

Järvinen (2001), technology enhanced learning

supports “naturally” learning by manipulation,

comparison and problem solving in a non-

prescriptive real-world-like context that leaves room

for creative thinking and innovation. Consequently,

one major reason for educationalists to embrace ICT

is because ICT enhanced learning seems to tally

with the central principles and objectives of

constructivist pedagogy.

The inspiration for this paper derives from Alavi

and Leidner (2001), who have called for research on

how technology, learning theory/practice and the

learners’ psychological processes are related and

influence one another. The knowledge is drawn from

the current theoretical and empirical research

literature on learning and on the impact of ICT on

learning. Methodologically, this is an exploratory

study, building on hermeneutic psychology and

philosophical argumentation.

103

Patokorpi E. (2006).

CONSTRUCTIVIST INSTRUCTIONAL PRINCIPLES, LEARNER PSYCHOLOGY AND TECHNOLOGICAL ENABLERS OF LEARNING.

In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems - HCI, pages 103-109

DOI: 10.5220/0002440901030109

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 CONSTRUCTIVIST

INSTRUCTIONAL PRINCIPLES

AND THE IMPACT OF ICT

Recent research literature indicates that there is a

fairly clear consensus on a broad set of constructivist

instructional strategies (see e.g. Järvinen, 2001;

Ahtee & Pehkonen, 1994; Jonassen, 1994;

Johansson, 1999; Poikela, 2002). First of all,

constructivist pedagogues underline the importance

of a larger goal that organizes smaller tasks into a

sensible whole, giving an incentive to take care also

of the less exciting intermediate routines. Learning

is not focused on separate facts but on a problem.

The learner needs to feel that the problem in some

way concerns him (i.e. to own the problem) in order

to be motivated to try to solve it. The problem

should be close to a problem in the real world.

Unlike in traditional teaching, in constructivist

learning there is no one right answer but many

possible solutions to a problem or at least if there is

one right solution, there are many alternative routes

to it.

It follows from what has been said above that it

is the learner and not the teacher who needs to take

in a significant degree the responsibility for

gathering knowledge. The learning environment,

too, should be in some sense similar to a real-world

environment. This usually means going out from the

traditional classroom, and learning things in their

authentic environment. The learner’s prior

knowledge, experience and skills should be taken

into account because the learner will better

understand and remember new things if they are

built on his prior knowledge and experience. People

are different, with different experiences, skills,

interests and goals. Constructivist education seeks to

take this fact into account by leaving room for

alternative individual learning strategies.

Constructivists underline the social aspect of

learning; all forms of interaction are encouraged,

and usually assignments involve teamwork or other

forms of cooperation. The final feature stressed by

constructivist pedagogues is guidance; the teacher’s

role is to facilitate learning by giving pieces of

advice and guiding onto the right direction.

Although teachers do not slavishly follow these

strategies every time, their impact on educational

practices is considerable.

A cursory look at what educationalists say about

ICT in education indicates that ICT-mediated

learning seems exceptionally well to tally with the

constructivist instructional principles. According to

Sotillo (2003), “New developments in wireless

networking and computing will facilitate the

implementation of pedagogical practices that are

congruent with a constructivist educational

philosophy. Such learning practices incorporate

higher-order skills like problem-solving, reasoning,

and reflection”. It seems that the students cooperate

more, work more intensively and are more

motivated than in conventional classroom teaching.

ICT enhanced teaching is an efficient equalizer,

levelling regional and social inequalities (Puurula

2002; Hussain et al., 2003). Langseth (2002) stresses

creativity and the fact that the pupils take

responsibility for their own work, and, instead of

using their logical and linguistic faculties, use a

“broader range of intelligences according to their

personal preferences” (pp. 124-125). Langseth

continues: “The web offers individuality in the sense

that you can choose your own pace, your own source

of information, and your own method; in a group or

alone” (p. 125; Hawkey, 2002; Kurzel et al., 2003).

Furthermore, the focus is on collaborative work, not

on the final product.

The above views are presumably quite

representative of the enlightened popular idea of

how ICT affects learning. All in all, ICT mediated

learning is supposed to be more democratic, more

personal, give broader skills, more creative, more

interactive, and so forth. To cut a long story short

one could say that both constructivist pedagogy and

ICT enhanced knowledge and learning are supposed

to be, by nature: cross-disciplinary, democratic,

personal, collaborative, independent and practical

(i.e. favour learning by doing). So, at least on the

surface, it seems that ICT mediated learning and the

constructivist educational doctrine is a match made

in heaven.

3 CRITICISM OF

CONSTRUCTIVISM

Instructional principles should be based on an

adequately correct understanding of the learning

process. According to Kivinen and Ristelä (2003),

cognitively oriented constructivists exaggerate the

role of cognitive structures in learning. Contrary to

what the constructivists say, what we humans do

(i.e. construct) when we learn is not primarily

cognitive structures but practical ways of doing

things (habits of action), which we are not

necessarily conscious of or able to articulate.

Consequently, the role of deliberation in learning is

ICEIS 2006 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

104

not quite as central as cognitive constructivists tend

to think. Constructivists also put too much emphasis

on verbal knowledge (Fox, 2001). For pragmatists,

in turn, words and ideas are tools like any other

man-made objects, and the creation of new

knowledge is the creation of new ways of verbal and

nonverbal action (Kivinen & Ristelä, 2003).

Likewise, as constructivists underline creativity and

the active construction of personal meaning, they at

the same time tend to ignore memorisation.

Memorisation still serves an important function in

everyday life and learning. Understanding without

remembering would send us to endlessly repeating

old errors (Fox, 2001).

The human innate capacities and the maturation

of the nervous system are not being sufficiently

taken into account by constructivists. In context we

passively absorb knowledge and adopt behavioural

patterns. Fox (2001) implies that constructivism is to

blame for the fact that nowadays teachers are

unwilling to confront "the upsetting differences in

innate ability or talent" (p. 33).

The role of training (drills) as part of learning is

not acknowledged nor appreciated enough by

constructivists. Training has its place in life because

certain routines need to be performed quickly and

correctly in order to enable us to direct our attention

to matters of greater consequence. Richard Fox's

(2001) example of training is a musician practising a

musical piece. Fox says, "to the extent that a trial is

an exact repetition of a previous trial, nothing has

been learnt. The point of practice, in this sense, is to

eliminate errors" (p. 32). Another favourite example

that pragmatists typically present is driving a car

(Kivinen & Ristelä, 2003). The above examples

nicely illuminate certain quite fundamental

differences between the constructivist and the

pragmatist views on learning. Consider the

following example. One may practice writing one's

signature, in which case an exact repetition implies

that something has been learned. Golf training is

another good example. Many golf players strive to

train their swing so that it would be exactly the same

every time. The difference in the trajectory of the

ball is introduced by changing the club.

Consequently, many cases of training have little or

nothing to do with creativity but the overriding aim

is to make the performance as machine-like and

repeatable as possible (Collins & Kusch, 1998). The

traditional method of authority, applying the

techniques of learning by rote, was used especially

in the Middle Ages to ensure that the learners’

performance adhered to and copied faithfully what

the Church Fathers had written down. Army drills is

another well-known example. Presumably, a more

veiled or forced point in Fox’s criticism is to imply

that constructivism is poor at eliminating errors. Fox

is perfectly right, but compared with the method of

authority neither constructivism nor pragmatism

succeeds very well in the elimination of errors.

Pragmatists recommend that learners concentrate

on the subject matter, not on the learning process

itself:

Practices encouraging the observation of one's own

learning as an end in itself can basically be seen as a

mere rejustification of testing that has traditionally

ruled school activities. Instead of the pupils being

taught new skills and knowledge, they are trained to

monitor their own studies. A gradual improvement in

the ability to work independently is quite rightly an

aim for education, but it is by no means self-evident

that this can be achieved or promoted by intensive

concentration on the operative aspects of one's own

thinking (Kivinen & Ristelä, 2003, p. 371).

Ignoring some obvious exaggerations, one could

say that the most salient point of criticism in the

above quotation is that too much introspection may

be harmful. In defence of constructivism, one could

say that it depends on what one is learning. Let us

take foreign language pronunciation as an example.

It stands to reason that a regular language learner

should not consciously focus on the performance of

the speech organs, unless there is a problem with the

pronunciation. However, for a foreign language

teacher trainee, who is learning to teach

pronunciation, it makes sense to focus on the

learning process itself (i.e. to consciously focus on

how the speech organs work). Likewise, correcting

speech impediments often requires conscious

attention to the learning process itself. These two

examples bring to light a genuine need for thinking

about thinking retrospectively – as opposed to

training in cases where there is no need to verbalise

or make conscious the task or process itself. So,

even student learners, not just university professors,

may need to think about their thinking in retrospect

for learning to be successful. In other words, to

know what one knows is in some cases a valid

learning goal by its own right.

4 SHERLOCK HOLMES MEETS

FORREST GUMP

A certain kind of view of the learning process suggests a

certain kind of (prototypical) learner profile.

Constructivists strongly stress the element of active

CONSTRUCTIVIST INSTRUCTIONAL PRINCIPLES, LEARNER PSYCHOLOGY AND TECHNOLOGICAL

ENABLERS OF LEARNING

105

construction in human thinking and perception. A central

inferential process behind the constructedness of human

experience is abduction, which is also the principal

method used by the famous literary figure, Sherlock

Holmes. Abduction conveys the manner in which people

reason when making discoveries in the sense of coming up

with new ideas. Hence, abduction is considered a logic of

discovery. As a logic of discovery, abduction is essentially

a matter of finding and following clues. The observation

of a clue is always in relation to the observer’s background

knowledge. The clues are there for all to see, which makes

knowledge by abduction democratic by nature. However,

all people do not detect these clues because the clues are

qualitative and unique. This sets the stage for knowledge

that is essentially personal. It is personal in the sense that

individuals differ in their ability to detect clues, due to

individual differences in their prior knowledge and

experience as well as logical acumen (Peirce, 1996;

Ginzburg, 1989; Peltonen, 1999).

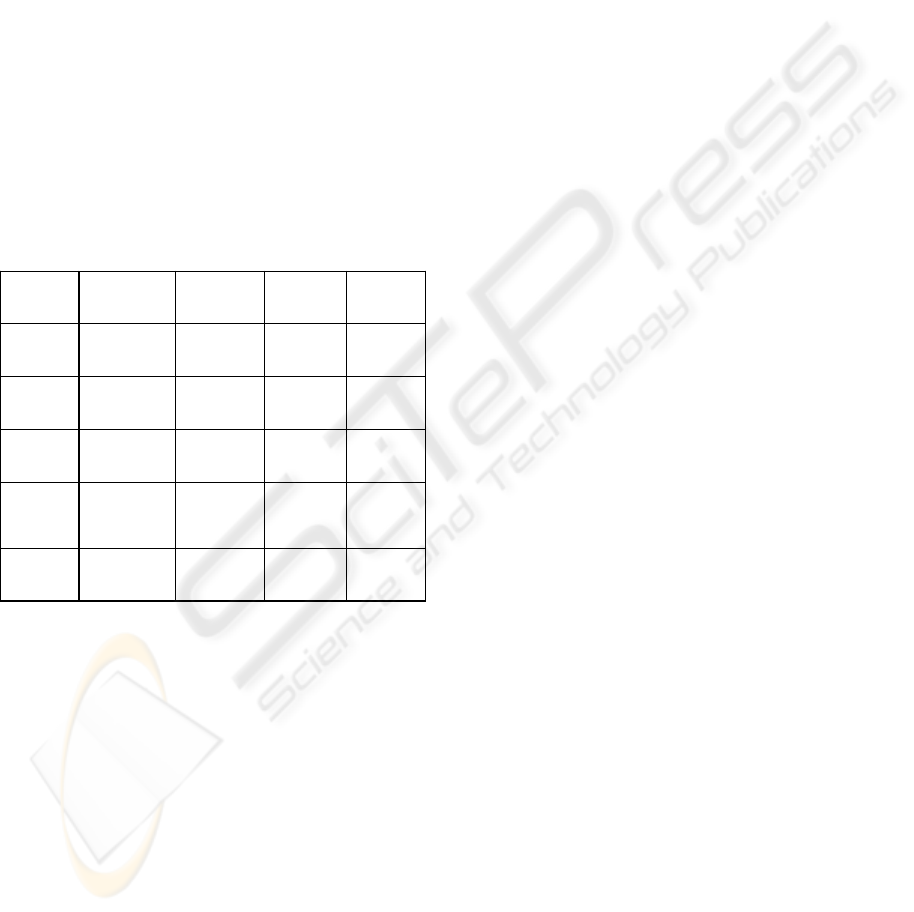

Table 1: Links between constructivist pedagogy,

psychology and technology.

As this very brief characterization of abductive

reasoning indicates, knowledge by abduction is, by

nature, personal, democratic, creative and based on

prior knowledge. A Sherlock Holmes type of learner

calls for laying out the learning materials as in a

detective story. Pragmatists imply that more often

than not deliberation is not worth the effort and one

should not worry too much about the potential

consequences of actions. The hero of the pragmatist

learning ideology is Forrest Gump, and his slogan is:

Just do it! The exhortation to go with one's gut

feeling is seductive to many, but it smacks of

irrationalism. Did Forrest Gump succeed because he

did not reflect upon the tasks he was given or

because he was dedicated, sympathetic and endowed

with special innate talents? Human-computer

interaction designers and researchers have noticed

that some users are reluctant to read the manual, and

rather resort to learning by doing (Carroll, 1990).

Forrest Gump, if anyone, seems to fall into this

category of users. Unfortunately, the Sherlock

Holmes of this world are no better themselves in this

respect, prone as they are to figure things out on

their own, hypothesize and overgeneralize.

Hopefully there will be room for both Forrest Gump

and Sherlock Holmes in each of us, although in

some cases neither of them gets it right.

5 LINK BETWEEN

TECHNOLOGY AND

EDUCATION

Empirical evidence for the beneficial impact of ICT

on learning is scarce (Gorard et al., 2003). One

reason for the scarcity is that we seem to lack the

ability to estimate the influence of ICT, owing both

to the complexity of ICT itself and disagreements

among researchers concerning empirical methods or

the interpretation of the findings (Jadad &

Delamothe, 2004). The brief and tentative discussion

below is based on the available empirical and

theoretical research literature, weighing the

arguments pro and con presented there.

Methodologically, the discussion applies the

hermeneutic psychology of Carroll and Kellogg

(1989; Carroll, 1997); the idea is to interpret the

psychological claims embodied in artefacts, or

rather, in whole technologies. Equipped with a

critical conception of the constructivist features of

learning, one should be able to see clearer than

before how well the constructivist pedagogy

matches the most prominent features of ICT. Other

important features of ICT enhanced learning of

course exist – for instance time-to-performance

(Wolpers, 2004), cost efficiency, time savings

(Marcus, 2000; Eales, 2004; Judge, 2004) and

quality (Inman & Kerwin, 1999) – but these features

lack a clear connection to psychological processes.

The table on the previous page lays out the

interconnections between the constructivist

pedagogy, psychology and technology, indicating

the weakest link in each row by italics. A similar

table with the pragmatist or, indeed, with the

knowledge-creation movement’s (Paavola et al.

2002) learning principles would look different.

It is generally assumed that both constructivism

and ICT provide ample leeway for integrating many

disciplines into a meaningful storyline, for instance

thanks to simulation technologies. Mobile

Instructional

theory:

Constructivism

Psychological

processes

Technological

enablers

Instructional

practice: ICT

enhanced

learning

Environment

related

factors

Problem-based,

Close to real life,

Many solutions

Abduction Mobile

technology,

Virtual reality,

Simulation

Cross-

disciplinary

Personality

related

factors

Prior knowledge,

Alternative

learning

strategies

Abduction,

Induction,

Deduction

Personalisation

technologies,

End-user

programming

Personal,

Cognitively

flexible,

Democratic

Action

related

factors

Learning by

doing or by

manipulation

Trial and error Simulation

technologies,

e.g. computer

games

Practical

Cognitive

factors

Learner

responsible for

searching

information

Motivation Information

retrieving

technologies,

e.g. the

Internet

Independent,

Democratic

Interactional

factors

Interactive Communicative

and team work

skills

Interactive

technologies,

e.g. hypertext

and email

Collaborative,

Democratic

ICEIS 2006 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

106

technologies, too, expand the potential of problem-

based learning environments, but to the direction of

the real world, as they enable the learner to go

outside of the traditional classroom. The weakest

link in the first row (environmental factors) is cross-

disciplinarity because therein the instructional

design is difficult to arrange, owing to a

compartmentalization of teaching subjects, inflexible

curricula, a lack of ICT skills and a lack of teacher

cooperation (cf. Spector, 2000). In other words,

attempts at cross-disciplinarity are riddled with the

practical problems of daily teaching arrangements

rather than with any fundamental problems in

technological support, pedagogical theory or learner

psychology.

Personalisation does not mean just

accommodating materials to fit the learners’

expectations, skills and experience but it also allows

students “to break away from the expert view and

follow personalised goals” (Kurzel et al., 2003).

Personalisation is a central enabler for ICT enhanced

learning, especially if and when learning breaks free

from the desktop environment and becomes mobile

and ubiquitous. Mobile devices are personal in the

sense of being rarely shared by other people. They

are also traceable, which makes it possible to link an

individual with a particular device, and therefore

tailor for instance services to suit the individual in

question. By personalisation is also meant the

malleability of the technology, allowing either the

user himself to mould and adjust some of the device

and interaction features or the technology to learn

about user preferences, and automatically adapt to

them (Lim et al. 2003, Smyth 2003). Unfortunately,

we are still very much trapped in the old world of

fixed computing platforms, accessed by users with

the same (personal) device from the same IP

address. Personalisation technology just is not yet

mature enough to support the creation of truly

personal knowledge (Dolog et al., 2004; Kurzel et

al., 2003). The creation of personal knowledge is

also hampered by barriers (e.g. copyright) to end-

user computing.

There are various advanced simulation

technologies that make simulated practice possible.

Learning by doing has not been challenged directly

by empirical research on ICT enhanced learning,

although there must be differences owing to whether

one is practical in the real world or in a virtual

world. Owing to the conceptual vagueness of the

term ‘practical,’ a closer scrutiny of the mental and

behavioural processes at work in these environments

seems to be called for.

The weakest link in the row of cognitive factors

is motivation because in case the learner does not

accept responsibility for seeking information, the

constructivist pedagogy seems to have no ready

remedy to it. How to motivate a learner to take

responsibility if he or she refuses to owe the

problem? Moreover, information technologies per se

do not give the user information seeking skills.

In an ICT enhanced learning environment the

constructivist principle of interactivity translates into

technology-enabled collaboration. There seem to be

no major problems in terms of supporting

technologies but collaborativeness partly

undermines or interferes with certain other

constructivist learning objectives. Constructivist

learning methods generally require more guidance

and feedback (Björkqvist, 1994). On the other hand,

ICT is supposed to free the teacher’s time for just

those activities. The dilemma here is that ICT

enhanced learning seems to take more, not less, of

the teacher’s time than traditional teaching (Eales,

2004; Judge, 2004). There is also a danger of too

efficient guidance or instruction, which means that

the facilitator ends up doing the learner’s work. A

suggested remedy is the maximization of peer

dialogue by means of interactive technologies

(Mayes, 2000; Saunders, 2002). However, when the

work is done independently in groups, i.e. away

from under the watchful eye of the teacher, it may

lead to free rider problems (Tétard & Patokorpi,

2005). Hence the problems with collaboration are

mainly in the area of instructional practice, as

teachers have trouble in handling collaborative

learning environments (Wielenga, 2002).

It is generally claimed by constructivists that ICT

enhanced learning makes learning more democratic.

Interaction is more democratic between the

knowledge source and the learner (Hussain et al.,

2003). It is also democratic in the equally narrow

sense of making the learner relatively independent of

others in the seeking of information, and in building

on the individual’s own prior knowledge and skills.

However, according to Gorard et al. (2003), ICT

cannot solve the social problems of inequality and

non-participation because it does not help to give

access to ICT when the reasons for non-participation

stem from prior long-term economic, educational

and social factors.

6 CONCLUSION

Artefacts as well as whole technologies embody

social, psychological and aesthetic preconceptions,

CONSTRUCTIVIST INSTRUCTIONAL PRINCIPLES, LEARNER PSYCHOLOGY AND TECHNOLOGICAL

ENABLERS OF LEARNING

107

directing and moulding the way we learn and live.

The designers as well as professional users of ICT

(e.g. teachers) should be aware of these

preconceptions. We should also become aware of

the blind spots that all learning theories have. Then,

having avoided these two above-mentioned pitfalls,

the teacher applying ICT in educational settings has

still to accommodate it into the real-life conditions

of the actual learning environment.

In order to critically examine the constructivists’

sweeping claim of the perfect match of constructivist

pedagogy and ICT, the paper has attempted to

unearth the central grievances related to the

interconnections of the constructivist instructional

method, psychological processes, technology and the

practical application of ICT in learning in the hope

that the match could be improved in the future. The

overall picture attained is sketchy and tentative as it

is based on whole technological domains, an

individual-psychological view of man and does not

focus on any clearly defined level of education or

group of learners. Nonetheless, a bird’s eye view

may be helpful in putting scattered empirical

observations into perspective.

Some general observations seem worth

underlining. Constructivists put much weight on the

learners’ own initiative and personal interests, which

per se seems commendable, but when the learner

lacks motivation the technology may be used for

mindless copying (plagiarism). The technology itself

can to a certain degree give guidance to the user, but

the skills in using for instance the information

retrieving technologies do not equal knowledge

seeking skills. Constructivists shun certain cognitive

processes, like memorisation, although suitable

supporting technologies abound. Lastly, it seems

that ICT enhanced cross-disciplinary and

collaborative learning are difficult to arrange in most

schools today mainly for practical reasons related to

the learning environment, rather than for theoretical

or technological reasons (Lehtinen 2003).

In terms of technology, the biggest hindrance to

a further development of constructivistically

oriented ICT enhanced learning seems to be

immature personalisation technologies, whereas the

biggest promise seems to be the mobile

technologies. Mobile technologies may be turning us

all into nomads, as has been claimed by some

visionaries (Keen & Mackintosh, 2001; Carlsson &

Walden, 2002). In a nomadic culture learning does

not take place in the classroom but wherever one is

in need of relevant information or new skills.

REFERENCES

Ahtee, M. & Pehkonen, E. (eds.) 1994, Constructivist

Viewpoints for School Teaching and Learning in

Mathematics and Science, Research Report 131.

Yliopistopaino, Helsinki.

Alavi, M. & Leidner, D.E. 2001, Research Commentary:

Technology-Mediated Learning – A Call for Greater

Depth and Breadth of Research, Information Systems

Research, vol. 12, No. 1, March 2001, pp. 1-10.

Björkqvist, O. 1994, Social constructivism and

assessment, in Ahtee, M. and Pehkonen, E. (eds.), pp.

19-26.

Carlsson C. & P. Walden 2002, Mobile Commerce: Some

Extensions of Core Concepts and Key Issues,

Proceedings of the SSGRR International Conference

on Advances in Infrastructure for e-Business, e-

Education, e-Science and e-Medicine on the Internet,

L’Aquila, Italy.

Carroll, J.M. & W.A. Kellogg 1989, Artifact as Theory-

Nexus: Hermeneutics Meets Theory-Based Design,

CHI’89 Proceedings, pp. 7-14.

Carroll, J.M. 1990, The Nurnberg Funnel: Designing

Minimalist Instruction for Practical Computer Skill,

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Carroll, J.M. 1997, Human-Computer Interaction:

Psychology as a Science of Design. Annual Review of

Psychology, vol. 48, pp. 61-83.

Collin, F. 2001, Bunge and Hacking on Constructivism,

Philosophy of the Social Sciences. Review Essay, Vol.

31, No. 3, pp. 424-453.

Collins, H. & M. Kusch 1998, The shape of actions: what

humans and machines can do, Cambridge (Mass.),

MIT Press.

Dolog, P., N. Henze, W. Nejdl & M. Sintek 2004,

Personalization in Distributed e-Learning

Environments, ACM, May 17-22. Available at

http://www.www2004.org/proceedings/docs/2p170.pd

f last visited 14.2.2005.

Eales, R. T.J. 2004, Crossing the Border: Comparing

Partial and Fully Online Learning, in e-Society 2003,

IADIS International Conference, pp. 218-225.

Flowers, L., E.T. Pascarella & C.T. Pierson 2000,

Information Technology Use and Cognitive Outcomes

in the First Year of College, The Journal of Higher

Education, Vol. 71, No. 6, pp. 637-667.

Fox, R. (2001) Constructivism Examined, Oxford Review

of Education, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 23-35.

Ginzburg, C. 1989, Ledtrådar. Essäer om konst, förbjuden

kunskap och dold historia, Stockholm: häften för

kritiska studier.

Gorard, S., N. Selwyn & L. Madden 2003, Logged on to

learning? Assessing the impact of technology on

participation in lifelong learning, International Journal

of Lifelong Education, Vol. 22, NO. 3, May-June, pp.

281-296.

Hawkey, R. 2002, The lifelong learning game: season

ticket or free transfer? Computers and Education, 38,

pp. 5-20.

ICEIS 2006 - HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTION

108

Hussain, H., Embi, Z.C. & Hashim, S. 2003, A

Conceptualized Framework for Edutainment,

Informing Science: InSite – Where Parallels Intersect,

pp. 1077-1083.

Inman, E. & M. Kerwin 1999, Instructor and students

attitudes toward distance learning, Community

College Journal for research and Practice, Vol. 23, No.

6, pp. 581-592.

Jadad, A.R. & T. Delamothe 2004, What next for

electronic communication and health care? BMJ, Vol.

328, pp. 1143-4. Available at:

bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/extract/328/7449/11

43 last visited 23.2.2005.

Järvinen, E-M. 2001, Education about and through

Technology. In search of More Appropriate

Pedagogical Approaches to Technology Education,

Acta Universitates Ouluensis, E 50. Oulun yliopisto,

Oulu.

Johansson, K. 1999, Konstruktivism i distansutbildning.

Studerandes uppfattning om konstrukivistisk lärande.

Umeå universitet, Umeå.

Jonassen, D.H. (1994) Thinking technology: toward a

constructivist design model, Educational Technology,

Vol. 34, Vol. 4, pp. 34-37.

Judge, M. 2004, The Wired for Learning Project in

Ireland. A Classic Tale of Technology, School Culture

and the Problem of Change, in e-Society 2003, IADIS

International Conference, pp. 226-235.

Keen, P.G.W. & R. Mackintosh 2001, The Freedom

Economy: Gaining the MCommerce Edge in the Era

of the Wireless Internet, New York:

Osborne/McGraw-Hill.

Kivinen, O. & P. Ristelä 2003, From Constructivism to a

Pragmatist Conception of Learning, Oxford Review of

Education, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 363-375.

Kuh, G. & N. Vesper 1999, Do Computers enhance or

detract from student learning? Paper presented at the

annual meeting of the American Educational Research

Association, Montreal, Canada.

Kurzel, F., Slay, J. & Hagenus, K. 2003, Personalising the

Learning Environment, Informing Science: InSite –

Where Parallels Intersect, pp. 589-596.

Langseth, I. 2002, Sense of Identity, in Karppinen, S.

(ed.), Neothemi-Cultural Heritage and ICT at a

Glance, Studia Pedagogica 28, Helsinki: Hakapaino,

pp. 123-128.

Lehtinen, E. 2003, "Computer-supported collaborative

learning: An approach to powerful learning

environments" In: De Corte, E., Verschaffel, L.,

Entwistle, N., Van Merriëboer, J. eds. Powerful

Learning Environments: Unravelling Basic

Components and Dimensions, Pergamon, Amsterdam,

pp. 35-54.

Leontjev, A.N. 1977, Toiminta, tietoisuus,

persoonallisuus, Kansankulttuuri, Helsinki.

Lim, E-P., Y.Wang, K-L. Ong, & S-Y. Hwang 2003, In

Search of Knowledge about Mobile Users, ERCIM

News No. 54, July, pp. 10-11.

Marcus, J. 2000, Online teaching’s costs are ‘high,

rewards low’, Times Higher Education Suppplement,

Vol. 21, January.

Mayes, T. 2000, A Discussion paper for the IBM Chair

presentation, May 18, 2000. Retrieved March 8, 2004

from http://www.ipm.ucl.ac.be/ChaireIBM/Mayes.pdf.

Paavola S., Lipponen, L., Hakkarainen K. 2002,

Epistemological Foundations for CSCL : A

comparison of three modes of innovative knowledge

communities. In G. Stahl, (Ed), 4

th

Computer Support

for Collaborative Learning: Foundations for a CSCL

Community, (CSCL-2002), Boulder, Colorado,

January 2002, pp.24-32, LEA, NJ. USA.

Peirce, C.S. 1996, Collected Papers 1931-58, C.

Hartshorne, P. Weiss and A. Burks. (eds.), Cambridge

(Mass.): Harvard University Press.

Peltonen, M. 1999, Mikrohistoriasta, Helsinki:

Gaudeamus.

Piaget, J. 1982, The Essential Piaget. Routledge, Kegan &

Paul, London.

Poikela, E. (ed.) 2002, Ongelmaperustainen pedagogiikka:

Teoriaa ja käytäntöä. Tampere University Press,

Tampere.

Puurula, A. 2002, Searching for a pedagogical basis for

teaching cultural heritage using virtual environments,

Karppinen, S. (ed.). Neothemi-Cultural Heritage and

ICT at a Glance. Studia Pedagogica 28, Helsinki:

Hakapaino, pp. 17-32.

Saunders, G. 2002, Introducing Technology onto a

Traditional Course: Turning the Classroom Upside

Down, The New Educational Benefits of ICT in

Higher Education: Proceedings, pp. 38-44.

Smyth, B. 2003, The Missing Link – User-Experience and

Incremental Revenue Generation on the Mobile

Internet. ERCIM News No. 54.

Sotillo, S.M. 2003, Pedagogical Advantages of Ubiquitous

Computing in a Wireless Environment, Case Studies,

May/June 2003, online at:

http://ts.mivu.org/default.asp?show=article&id=950

accessed 25.5.2004.

Spector, J.M. 2000, Trends and Issues in Educational

Technology: How Far We Have Not Come,ERIC IT

Newsletter, 12(2). Available at

http//www.ericit.org/newsletter/docs/ last visited

1.2.2005 .

Tétard, F. & E. Patokorpi 2005, A Constructivist

Approach to Information Systems Teaching: A Case

Study on a Design Course for Advanced-Level

University Students, Journal of Information Systems

Education, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 167-176.

Vygotsky, L.S. 1969, Denken und Sprechen. Fischer,

Frankfurt am Main.

Wielenga, D.K. 2002, Probing and Proving Competence,

The New Educational Benefits of ICT in Higher

Education: Proceedings, pp. 12-17.

Wolpers, M. 2004, Promoting E-Learning Research and

Application Scenarios in Europe, Proceedings of the

ICL Conference, Villach, Austria, September 2004.

CONSTRUCTIVIST INSTRUCTIONAL PRINCIPLES, LEARNER PSYCHOLOGY AND TECHNOLOGICAL

ENABLERS OF LEARNING

109