UNDESIRABLE AND FRAUDULENT BEHAVIOUR IN ONLINE

AUCTIONS

Jarrod Trevathan

School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences

James Cook University

Wayne Read

School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences

James Cook University

Keywords:

Bid shielding, shilling, sniping, siphoning, non-existent/misrepresented items.

Abstract:

Online auctions are a popular means for exchanging items over the Internet. However, are many inherent

security and fairness concerns. Participants can behave in an undesirable and fraudulent manner in an attempt

to gain an advantage at the expense of rivals. For example, a bidder might seek to suppress the price by bid

sniping, or the seller could introduce fake bids to inflate the price. In addition, an outsider or rival seller can

lure away bidders by directly offering them better deals, or a malicious seller can auction mis-represented or

non-existent items. This conduct is a problem as it results in market failure, thereby inhibiting the usefulness of

online auctions as an exchange medium. While cryptography has been used to provide security in terms of bid

authentication and privacy, there is no documented means to prevent many of the aforementioned problems.

This paper investigates undesirable and fraudulent behaviour in online auctions. We examine the following

practices: bid shielding, shill bidding, bid sniping, siphoning and selling non-existent or misrepresented items.

We describe the characteristics of such behaviour and how to identify it in an auction. We also provide

recommendations for recourse against undesirable and fraudulent participants.

1 INTRODUCTION

Online auctions are one of the most popular destina-

tions on the web. Buyers and sellers can exchange

items amongst a worldwide audience from the com-

fort and privacy of their own homes. Participants re-

main largely anonymous and can bid in any manner

they desire. However, this freedom comes at the ex-

pense of new security risks and fairness concerns.

By behaving in an undesirable or fraudulent man-

ner, one party is able to gain at the expense of an-

other. For example, bidders can use practices such as

bid shielding and bid sniping to keep the price low.

Alternately, shill bidding is a strategy which a seller

may pursue, to artificially inflate the auction price. In

addition, siphoning is a tactic employed by an out-

sider, who is seeking to profit from an auction by of-

fering bidders a cheaper, identical item. Finally, a

seller might attempt to auction a non-existent or mis-

represented item.

Auction security has been previously discussed in

(Franklin and Reiter, 1996; Stubblebine and Syver-

son, 1999; Trevathan et al, 2005). Cryptographic

methods have been proposed to solve many of these

security issues (see e.g., (Franklin and Reiter, 1996;

Viswanathan et al, 2000; Trevathan et al, 2006)).

However, cryptographic solutions are generally lim-

ited to bid authentication and privacy. Protecting auc-

tion participants from the aforementioned problems

is a much harder task (i.e., a bidder’s bidding strategy

or misrepresented goods). Furthermore, none of the

proposed models in literature specifically address the

auction format used in online auctions.

This paper discusses undesirable and fraudulent

practices in online auctions. We describe the char-

acteristics of such behaviour, and show how auction

participants can identify if they are a victim. We

also provide recommendations/options for what to do

when such behaviour is encountered. We show how

behaviours are related, and when an auction exhibits

one form of undesirable behaviour, the other forms

soon manifest to counter balance it. This inevitably

leads to market failure, and retards the usefulness of

online auctions as an exchange medium.

This paper is organised as follows: Section 2 de-

scribes the basic format and rules of a typical on-

line auction. Sections 3 through 7 discuss each ma-

jor form of undesirable auctioning behaviour. Each

of these sections includes a description of individ-

ual behavioural characteristics, remedies/recourse for

450

Trevathan J. and Read W. (2006).

UNDESIRABLE AND FRAUDULENT BEHAVIOUR IN ONLINE AUCTIONS.

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Security and Cryptography, pages 450-458

DOI: 10.5220/0002100704500458

Copyright

c

SciTePress

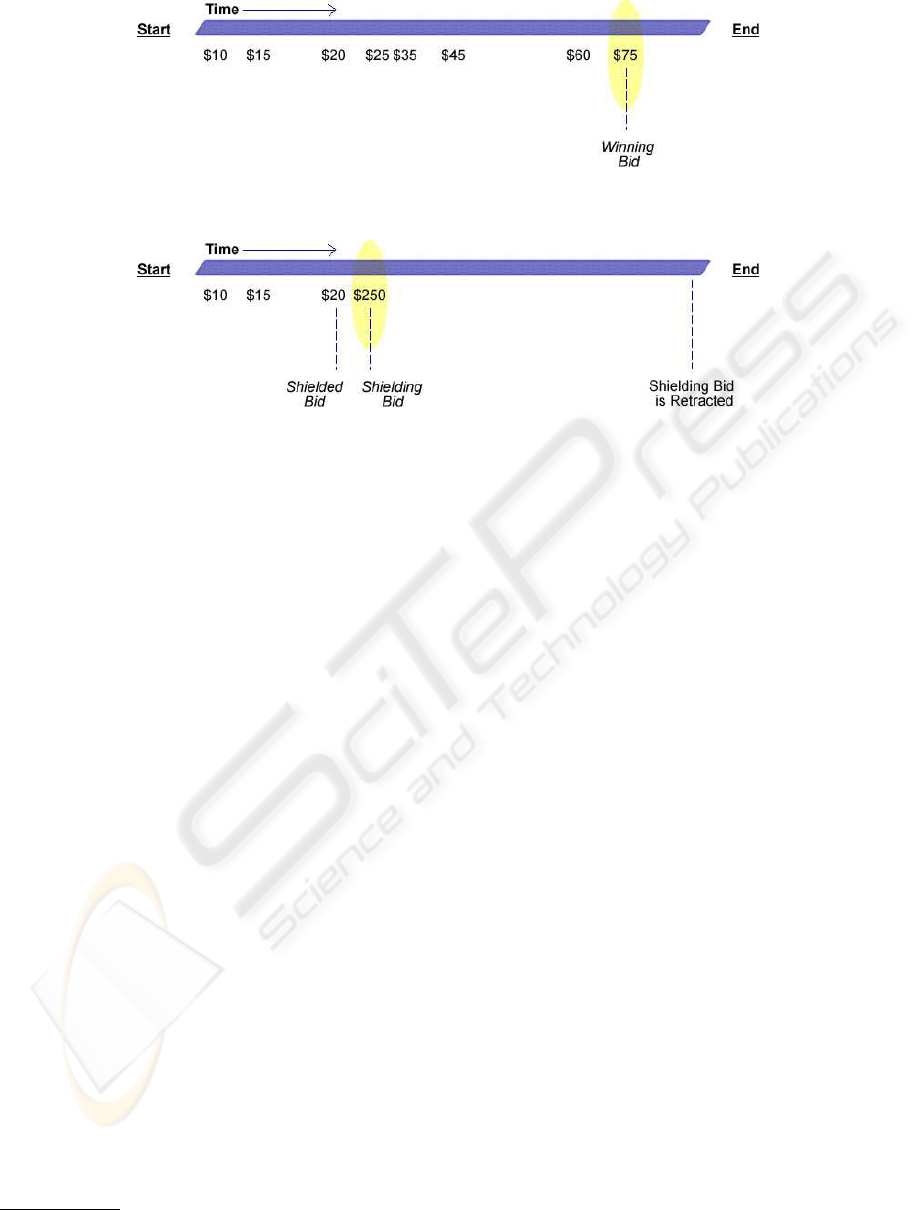

Figure 1: An Example Online Auction.

Figure 2: Bid Shielding.

victims and relationships between certain types of

behaviour. Section 8 provides some concluding re-

marks.

2 ONLINE AUCTIONS

There are many types of auction (e.g., Vickrey, CDA,

etc.). The most popular type of auction is the English

auction. In an English auction, bidders outbid each

other in an attempt to win an item. The winner is

the bidder with the highest bid. English auctions are

commonly employed in online auctions such as those

offered by eBay

1

and ubid

2

Online auctions differ to traditional auctions in that

the auction ends after a given period of time. Fig-

ure 1 illustrates a typical online auction (such as that

offered by eBay). Time flows from left to right. Bid-

ders can only submit bids between the auction start

and end times. Each bid must be for an amount that is

greater than the current highest bid. When the auction

terminates, the winner is the bidder with the highest

bid (in this case $75).

eBay and ubid offer a mechanism for automatically

bidding on a bidder’s behalf. This is referred to as the

proxy bidding system on eBay, and the bid butler on

ubid. A bidder is only required to enter the maximum

price they are willing to pay. The bidding software

will then automatically outbid any other bid until the

maximum, potentially saving the bidder money. Such

1

http://www.ebay.com

2

http://www.ubid.com

mechanisms remove the need for a bidder to be con-

stantly watching an auction for bidding activity.

3 BID SHIELDING

Bid shielding typically involves several bidders work-

ing in collusion with each other, or a bidder with ac-

cess to multiple accounts. The first bidder enters a

bid for the amount they are willing to pay for an item.

A second bidder then immediately enters an exces-

sively high bid in an attempt to deter other bidders

from continuing to bid. As the auction is drawing to

a close, the second bid is retracted. When this occurs,

the next highest bid remaining (i.e., the first bid) then

becomes the winning bid.

Figure 2 illustrates a bid shielding scenario. Ini-

tially regular bidders make a few bids ($10 and $15 in

this case). The first colluding bidder enters his/her bid

for $20. This is referred to as the shielded bid. The

second colluding bidder then enters a bid for $250,

which is well above the current bidding range, and is

unlikely to be outbid. This is known as the shielding

bid.

In the example, the shielding bid deters regular bid-

ders from bidding again. Prior to the end of the auc-

tion, the second colluding bidder retracts the shielding

bid for $250. The winning bid then falls back to the

shielded bid for $20. As the bid is retracted near the

end of the auction, other bidders do not have time to

respond. By this stage, most regular bidders have lost

interest in the auction anyway.

Bid shielding generally cannot be accomplished as

shown in the example due to the presence of software

UNDESIRABLE AND FRAUDULENT BEHAVIOUR IN ONLINE AUCTIONS

451

Figure 3: Bid Shielding in Auctions with Automated Bidding Agents.

bidding agents (i.e., eBay’s proxy bidding system).

As soon as the shielding bid is entered, the bidding

history won’t show this as a bid for $250. Instead, this

will be listed as the minimal amount required to out-

bid the shielded bid (e.g., $21, as $1 is the minimum

increment). Rival bidders will then be inclined to con-

tinue bidding, which in turn drives up the shielding

bid’s value.

Bid shielding in the presence of automated bidding

agents can be achieved by using two shielding bids.

Figure 3 illustrates this scenario. As in the previ-

ous example, a shielded bid for $20 is submitted. A

shielding bid for $250 is entered followed immedi-

ately by another shielding bid for $260. As the sec-

ond shielding bid outbids the first, the bidding his-

tory immediately reflects the value of the first shield-

ing bid (i.e., $250), thus giving the appearance of a

high price. Near the end, both of the shielding bids

are retracted. The winning bid then drops to $20 (i.e.,

the shielded bid).

This sort of behaviour disadvantages the seller in

terms of suppressing the price. Honest bidders are

also disadvantaged as they are forced out of the auc-

tion.

There are no mechanisms in place to prevent bid

shielding. Most auctioneers keep a record of the num-

ber of bid retractions made by a bidder. However, the

purpose for the record keeping is actually to deter bid-

ders from reneging on winning bids (i.e., win and then

later decide they don’t want the good). Retractions

that occur before an auction terminates are also typi-

cally deemed less suspicious than those that occur af-

terwards. Furthermore, keeping records on retraction

rates is largely useless as bidders can simply register

under different aliases.

Another type of price suppressing behaviour is re-

ferred to as pooling or bid rigging. Two or more bid-

ders collude, and agree not to bid up the price. How-

ever, this attack is only effective if the number of bid-

ders is small, or the majority of bidders are in collu-

sion.

4 SHILL BIDDING

Shill bidding (or shilling) is the act of introducing

fake bids into an auction on the seller’s behalf in or-

der to artificially inflate the price of an item. Bidders

who engage in shilling are referred to as shills. To

win the item, a legitimate bidder must outbid a shill’s

price. If one of the shills accidentally wins, then the

item is re-sold in a subsequent auction. Shill bidding

is a problem as it forces legitimate bidders to pay sig-

nificantly more for the item.

In March 2001, a U.S. federal grand jury charged

three men for their participation in a ring of fraud-

ulent bidding in hundreds of art auctions on eBay

(see (Schwartz and Dobrzynski, 2002)). The men cre-

ated more than 40 user IDs on eBay using false regis-

tration information. These aliases were used to place

fraudulent bids to artificially inflate the prices of hun-

dreds of paintings they auctioned on eBay.

The men hosted more than 1,100 auctions on eBay

from late 1998 until May 2000, and placed shill bids

on more than half of those auctions. The total value

of the winning bids in all auctions which contained

shill bids exceeded approximately $450,000. The to-

tal value of the shill bids in these auctions exceeded

approximately $300,000 (equivalent to 66%).

To be effective, a shill must comply to a particular

strategy which attempts to maximise the pay-off for

the seller. This section provides an insight into the

general behaviour of shills. It describes a shill’s char-

acteristics and strategies, presents examples of shill

behaviour in an auction, and discusses shill detection

techniques.

4.1 Shill Mindset

The main goal for shilling is to artificially inflate the

price for the seller beyond the limit that legitimate

bidders would otherwise pay to win the item. The

pay-off for the seller is the difference between the fi-

nal price and the uninflated price. A shill’s goal is to

lose each auction. A shill has an infinite budget. If the

shill wins, the item will have to be re-auctioned. Re-

sale of each item costs the seller both money and ef-

fort thereby eroding the possible gains from shilling.

SECRYPT 2006 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SECURITY AND CRYPTOGRAPHY

452

Figure 4: Aggressive Shill Bidding.

The shill faces a dilemma for each bid they submit.

Increasing a bid could marginally increase the rev-

enue for the seller. However, raising the price might

also result in failure if it is not outbid before the auc-

tion terminates. The shill must decide whether to take

the deal or attempt to increase the pay-off.

On the contrary, a bidder’s goal is to win. A bidder

has a finite budget and is after the lowest price possi-

ble. Increasing a bid for a legitimate bidder decreases

the money saved, but increases the likelihood of win-

ning.

4.2 Shill Characteristics and

Strategies

A shill has the following characteristics:

1. A shill usually bids exclusively in auctions only

held by one particular seller, however, this alone is

not sufficient to incriminate a bidder. It may be the

case that the seller is the only supplier of an item

the bidder is after, or that the bidder really trusts

the seller (usually based on the reputation of previ-

ous dealings).

2. A shill tends to have a high bid frequency. An

aggressive shill will continually outbid legitimate

bids to inflate the final price. Bids are typically

placed until the seller’s expected payoff for shilling

has been reached, or until the shill risks winning

the auction (e.g., near the termination time or dur-

ing slow bidding).

3. A shill has few or no winnings for the auctions par-

ticipated in.

4. It is advantageous for a shill to bid within a small

time period after a legitimate bid. Generally a shill

wants to give legitimate bidders as much time as

possible to submit a new bid before the closing time

of the auction.

5. A shill usually bids the minimum amount required

to outbid a legitimate bidder. If the shill bids an

amount that is much higher than the current highest

bid, it is unlikely that a legitimate bidder will sub-

mit any more bids and the shill will win the auction.

6. A shill’s goal is to try and stimulate bidding. As

a result, a shill will tend to bid more closer to the

beginning of an auction. This means a shill can

influence the entire auction process compared to a

subset of it. Furthermore, bidding towards the end

of an auction is risky as the shill could accidentally

win.

The most extreme shill bidding strategy is referred to

as aggressive shilling. An aggressive shill continu-

ally outbids everyone thereby driving up the price as

much as possible. This strategy often results in the

shill entering many bids.

In contrast, a shill might only introduce an initial

bid into an auction where there has been no prior

bids with the intent to stimulate bidding. This kind

of behaviour is a common practice in both traditional

and online auctions. However, most people typically

do not consider it fraudulent. Nevertheless it is still

shilling, as it is an attempt to influence the price by

introducing spurious bids.

This is referred to as benign shilling in the sense

that the shill does not continue to further inflate the

price throughout the remainder of the auction. A be-

nign shill will typically make a “one-off” bid at or

near the very beginning of the auction.

Regardless of the strategy employed, a shill will

still be a bidder that often trades with a specific seller

but has not won any auctions.

Another factor that affects a shill’s strategy is the

value of the current bid in relation to the reserve price.

For example, once bidding has reached the reserve

price, it becomes more risky to continue shilling.

However, this is conditional on whether the reserve is

a realistic valuation of the item that all bidders share.

4.3 Shill Bidding Examples

Figure 4 illustrates an example auction with aggres-

sive shilling. The shill aggressively outbids a legit-

imate bid by the minimal amount required to stay

ahead, and within a small time period of the last bid.

The shill bids force the other bidders to enter higher

bids in order to win. The shill does not win the auc-

tion despite the high number of bids;

UNDESIRABLE AND FRAUDULENT BEHAVIOUR IN ONLINE AUCTIONS

453

Figure 5: Benign Shill Bidding.

Figure 5 illustrates an example auction with benign

shilling. Initially no bids have been made. A shill

bid is entered for $10 to try stimulate bidding. After

seeing that there is some demand for the item, other

bidders eventually submit bids for the item. The shill

does not enter any further bids.

4.4 Shill Detection

There is often much confusion regarding what con-

stitutes shill behaviour. Bidding behaviour that might

seem suspicious could in fact turn out to be innocent.

Furthermore, a shill can engage in countless strate-

gies. This makes it difficult to detect shill bidding.

While the online auctioneers monitor their auctions

for shilling, there is no academic material available

on proven shill detection techniques.

(Wang et al, 2002) suggest that listing fees could

be used to deter shilling. Their proposal charges a

seller an increasing fee based on how far the winning

bid is from the reserve price. The idea is to coerce

the seller into stating their true reserve price, thereby

eliminating the economic benefits of shilling. How-

ever, this method is untested and does not apply to

auctions without reserve prices.

We are developing techniques to detect shill bid-

ding (Trevathan and Read, 2005). Our method ex-

amines a bidder’s bidding behaviour over several auc-

tions and gives them a shill score to indicate the de-

gree of suspicious behaviour they exhibit. Bidders

who engage in suspicious price inflating behaviour

will rate highly, whereas those with more regular bid-

ding behaviour will rate low. A bidder can examine

other bidder’s shill scores to determine whether they

wish to participate in an auction held by a particular

seller.

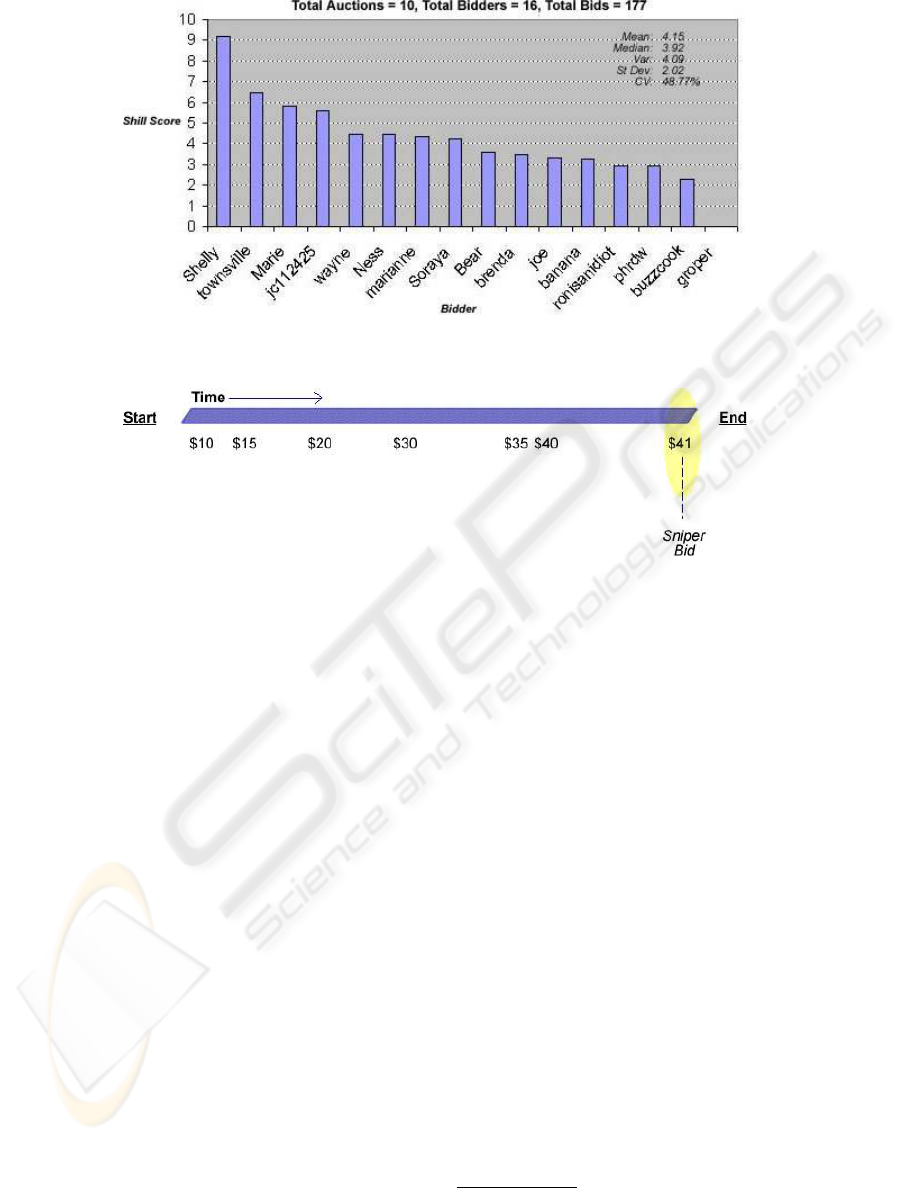

The shill score has been tested using simulated auc-

tions involving real world people. To facilitate testing

we implemented an online auction server (see (Tre-

vathan and Read, 2006)). Several types of tests have

been conducted. The first type involves auctioning

fake items to real bidders. Each bidder is allocated

a random amount of money, which they use to bid

in the auction. Even though bidders don’t actually re-

ceive the item, these tests manage to recreate the men-

tal drive and desire to win. Winners are excited and

often boastful after a hard fought auction. One per-

son (namely the author) is tasked with being a shill

in order to stimulate bidding. The shills goal is to in-

crease the price as much as possible, without actually

winning the auction.

When the shill score is used on these auctions, it

clearly identifies the shill bidder. It also exonerates in-

nocent bidders that bid in a regular manner. The shill

scores for a series of tests is given in Figure 6. In this

case, the bidder known as Shelly is the shill bidder.

Shelly engaged in aggressive shilling behaviour and

consequently has a shill score that is over nine. This

is clearly much higher than the other bidders. The

results from these tests are thus far encouraging.

We have also conducted similar auctions using real

items (e.g., bottles of wine and collector’s edition

playing cards), where the winner was required to pay

real money. In these settings, bidders are more cau-

tious. However, the shill was still able to influence

the auction proceedings and also was detected by the

shill score. (Note that all shilling victims were fully

reimbursed!) Furthermore, the shill score has been

tested using commercial auction data and simulations

involving automated bidding agents.

5 BID SNIPING

Bid sniping is another undesirable type of bidding be-

haviour. A bidder who employs a sniping strategy is

referred to as a sniper. A sniper will only bid in the

closing seconds of an auction, thereby denying other

bidders time to react. This essentially prevents the

sniper from being outbid.

Figure 7 illustrates the mechanics of bid sniping.

Regular bidders enter their bids as normal. In the clos-

ing seconds, the sniper enters a bid for the minimum

required to win (i.e., $41). The bid entered by a sniper

is referred to as a sniper bid. None of the other bid-

ders have time to outbid the sniper bid, and therefore

the sniper wins.

Sniping behaviour is the exact opposite of shilling.

A sniper’s goal is to win the auction for the lowest

SECRYPT 2006 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SECURITY AND CRYPTOGRAPHY

454

Figure 6: An example of the Shill Score when run on auction simulations containing one aggressive shill.

Figure 7: Bid Sniping.

price. Whereas a shill’s goal is not to win and to in-

flate the price. Sniping is often used as a preventa-

tive measure against shilling. A sniper may not be

able to prevent shilling occurring during an auction.

However, the sniper can prevent themselves from be-

ing shilled.

Sniping disadvantages regular bidders in that they

are denied the opportunity to respond to the sniper

bid. Bidders are typically frustrated when they realise

that sniping has occurred. This is especially the case

when a bidder has observed an auction for a long pe-

riod of time, only to be beaten in the closing seconds.

The seller is also potentially disadvantaged by snip-

ing, as the sniper bid does not stimulate rival bidding,

that might have occurred, had other bidders been able

to respond.

Sniping is permitted on eBay, although its use is

discouraged. Instead eBay recommends that a bidder

should only place a single bid at his/her maximum

valuation using the proxy bidding system. Despite

this recommendation, sniping is rampant, and is now

considered as a natural part of the online auctioning

experience. (Shah et al, 2002) performed a study into

the amount of sniping in 12, 000 eBay auctions. Their

results showed for the majority of auctions, a signifi-

cant fraction of bidding occurs in the closing seconds.

A sniping agent is a software bidding agent that fol-

lows a sniping strategy. The sniping agent constantly

monitors an auction, and waits until the last moment

to bid. Many companies now exist such as Bidnap-

per.com

3

, ezsniper

4

and Auction Sniper

5

which of-

fer sniping agents for use on eBay auctions.

uBid auctions differ to eBay in that auctions termi-

nate using a timeout session. Once the ending time of

an auction has been reached, the auction is extended

for ten minutes for each bid received. This limits

the effectiveness of sniping, but can lead to a show

down between snipers. As a result the auction can run

for a lot longer than the seller anticipated. The seller

can enforce a maximum extension limit to prevent the

auction continuing indefinitely. However, this results

in the auction being essentially the same as a normal

auction without a timeout session.

The only preventative measure for a bidder against

sniping, is to “out-snipe” the sniper. However, this

often results in there being multiple snipers in an auc-

tion. This behaviour leads to failure of the English

auctioning process. If everyone engaged in sniping,

the auction would essentially become a sealed bid

auction. In a sealed bid auction, bidders submit their

bids secretly during a bidding round. At the close of

3

http://www.bidnapper.com

4

http://www.ezsniper.com

5

http://www.auctionsniper.com

UNDESIRABLE AND FRAUDULENT BEHAVIOUR IN ONLINE AUCTIONS

455

bidding, the Auctioneer determines the winner. En-

glish auctions on the other hand are open bid, and al-

low bidders to bid multiple times. In a traditional of-

fline English auction, sniping cannot occur. Sniping is

a feature unique to online auctions. Sniping behaviour

blurs the boundaries of an online auction between the

type of auction it is and the rules that govern it.

6 SIPHONING

Siphoning (or bid siphoning) refers to the situation

where an outsider observes an auction and contacts

bidders offering them an identical item at a better

price. The outsider is referred to as a siphoner, and is

said to “siphon” bids from the auction. The siphoner

benefits in that he/she does not incur any of the costs

involved with organising and advertising an auction.

Siphoning disadvantages the Auctioneer through

lost revenue. That is, the siphoner does not have to

pay the Auctioneer to list/advertise an item. Siphon-

ing also disadvantages the seller whose auctions are

being siphoned. This is in a form of price under-

cutting (i.e., the siphoner offers the item at a better

price), and reduces the demand for the seller’s items.

A bidder who does business with a siphoner loses the

protection offered by the auction, and exposes them-

selves to fraud (e.g., misrepresented or non-existent

items).

Siphoning may also be used in conjunction with

shilling. When a shill bid accidentally wins, the seller

of the item can contact the next highest bidder, and

directly offer them the item. This saves the seller the

time and expense of re-auctioning the item.

Consider the following scenario: A seller is auc-

tioning off a traditional Japanese sword. A legitimate

bidder enters a bid for $1000. The seller then enters

a shill bid for $1200. The legitimate bidder refrains

from bidding and the shill bid wins. Later on the le-

gitimate bidder is approached by the seller. The seller

claims that the winner is a dead beat

6

, or has backed

out of the deal due to financial or other personal rea-

sons. The seller then offers the item to the bidder at,

or near, the bidder’s price of $1000.

Siphoning combined with shilling disadvantages

both the bidders and the Auctioneer. Bidders are

forced into paying an inflated price due to the shill

bids. The siphoning component this time does not

affect the seller, but rather the Auctioneer. This is be-

cause the seller does not have to repeat the auction and

is denying the Auctioneer revenue from listing fees.

The seller in effect has “siphoned” bids from his/her

own future auctions.

6

A bidder that has won an auction and to fails to make

payment.

Siphoning is impossible to detect by the Auctioneer

alone. Instead bidders must report the behaviour once

it has happened to them. However, most bidders are

aware of what siphoning is, and probably wouldn’t

recognise that they have been siphoned. Furthermore,

if a bidder receives a better price, or an item they re-

ally want, then they would not see such behaviour as

undesirable. In this case they are unlikely to report it.

There is no clear law regarding siphoning. The

only advice to bidders is to decline communication

with anyone that contacts them outside of the official

channels. In addition, if you were not the winner of

an auction, don’t accept an item from the seller after

the auction has ended.

7 NON-EXISTENT OR

MISREPRESENTED ITEMS

A dubious seller might attempt to auction a non-

existent item, or misrepresent an item. In the first

instance, the seller accepts payment from the buyer

but doesn’t deliver the item. In the second, the seller

misrepresents the item by advertising it as something

it isn’t, or delivers an item of lesser value. In the shill

case described in Section 4, the men misrepresented

paintings as being significant works when they were

inexpensive replicas (see (Schwartz and Dobrzynski,

2002)).

To ensure that an item conforms to its description,

eBay recommends that buyers study the seller’s pho-

tos. However, this is unsatisfactory as the seller can

simply copy pictures from a legitimate item, and post

these for the non-existent/misrepresented item.

eBay also recommends asking the seller questions

regarding the item. However, a seller may simply lie.

Furthermore, some bidders might be reluctant to ask

questions as they desire anonymity. For example, if

the bidder has a high profile, they might want to con-

ceal the fact that they are bidding. This might oc-

cur in the case where the bidder feels that their pri-

vacy would be compromised in some manner (e.g., re-

veal that they have a fetish for an item), change other

bidders’ perceptions of the item (e.g., stimulate un-

wanted bidding), or influence the seller to raise the

reserve price.

Another recommendation is to check seller feed-

back. eBay has a system where buyers and sellers

can leave feedback regarding their dealings with each

other. A party to a transaction can rate their experi-

ence as either good, neutral or bad. An individual is

given a rating based on the feedback received. How-

ever, feedback ratings are not a reliable measure of

an individual’s integrity, and feedback can be falsely

generated using multiple bidder accounts.

Online auctioneers offer a dispute resolution proce-

SECRYPT 2006 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SECURITY AND CRYPTOGRAPHY

456

dure where a buyer can initiate action against a seller

if an item was not received, or if the item is different

from what was expected. If a seller constantly does

not deliver items, the Auctioneer can revoke his/her

account. However, the seller can simply re-register

under a different alias.

Insurance can be offered to buyers for items not de-

livered. eBay has created a successful off-shoot busi-

ness, PayPal

7

, for guaranteeing online transactions.

However, launching an insurance claim can be an ar-

duous process, and might not fully compensate the

victim. Furthermore, it can require the compensated

funds to be spent by participating in future auctions.

In addition, it is only a solution that can be used after

fraud has occurred.

Escrow fraud is an emerging threat to online auc-

tions. A fraudster sets up a fake escrow service for

paying a seller for an item. When the winning bid-

der wires the money to the escrow agency, the agency

vanishes along with the payment. Neither the seller

receives the payment, nor does the winner receive the

item. The following are typical characteristics of an

escrow scam:

1. Check for poor grammar on the escrow site.

2. Although site may look authentic, it is usually

copied from a legitimate site such as Escrow.com

8

and Auctionchex

9

.

3. There are obvious give-aways in the Terms page,

which is generally stolen from another site.

4. A site will often leave hints of what its previous

incarnation was - especially if they’ve just changed

domain names recently.

5. Be wary if the seller insists on using a specific es-

crow site. Sellers don’t usually press for escrow,

buyers do.

Bidders must be wary of the escrow service they use,

and not do business with unknown or un-trusted es-

crow vendors.

8 CONCLUSIONS

Online auctions are susceptible to undesirable and

fraudulent behaviour. Such behaviour is designed to

influence the auction in a manner that either favours

a bidder, the seller, or an outsider seeking to profit

from the auction. This results in market failure, and

reduces the usefulness of online auctions as an ex-

change medium.

This paper investigates undesirable and fraudulent

trading behaviour, and discusses its implications for

7

http://www.paypal.com

8

http://www.escrow.com

9

https://auctionchex.com

online auctioning. We show how to identify such

behaviour and give recommendations for recourse

against undesirable and fraudulent participants.

Bid shielding is a practice employed by one or

more bidders to suppress bidding and keep the price

low. There is no means to protect against bid shield-

ing, other than to exclude users with a high bid retrac-

tion rate. However, a bidder can use a fake name to

re-register.

Alternately shill bidding is a practice employed by

the seller to artificially inflate the price by introduc-

ing spurious bids. Shill bidding is strictly forbidden

by commercial online auctions, and is a prosecutable

offence. There is limited material on shill bidding and

prevention/detection techniques. We are presently de-

veloping a method to detect shill bidders by giving

them a ranking called a shill score. A bidder can use

the shill score to decide whether they want to partici-

pate in an auction held by a particular seller.

Bid sniping is a strategy employed by a bidder to

prevent being outbid. A sniper submits a bid dur-

ing the closing seconds of an auction, thereby deny-

ing other bidders time to react. Many bidders engage

in sniping behaviour in an attempt to prevent them-

selves from being shilled. Sniping is permitted in on-

line auctions, but is discouraged. Commercial sniping

agents are available that engage in sniping behaviour

on the bidder’s behalf. Sniping can be reduced by en-

forcing a timeout limit which extends the auction by

several minutes for each new bid received after the

auction’s termination time. The prominence of snip-

ing behaviour raises concerns regarding the effective-

ness of online auctions to conduct English auctions

according to traditional rules.

Siphoning refers to the situation where an outsider

observes an auction and offers an identical item to the

bidders at a lower price. The siphoner avoids all of

the costs associated with conducting an auction, and

effectively profits from the seller. Siphoning is often

used in conjunction with shilling, and scams involv-

ing non-existent or misrepresented items. Siphoning

behaviour should be reported to the Auctioneer, how-

ever, there is little more that can be done.

A malicious seller can offer non-existent or misrep-

resented items to profit from unsuspecting buyers. It

is recommended that bidders inspect photos and ask

questions. However, a seller can post fake photos, lie

in response to questions, and a buyer might want to re-

main anonymous. eBay’s feed back rating is a mecha-

nism for gauging the integrity of a buyer/seller, how-

ever, it is dubious at best. Insurance can reimburse

victims of fraud, but is not a complete solution. Es-

crow fraud is emerging as a threat to insurance-based

fraud prevention measures and is difficult to identify.

The best advice is for a buyer to be wary of the goods

they are bidding for.

The popularity of online auctions and the over-

UNDESIRABLE AND FRAUDULENT BEHAVIOUR IN ONLINE AUCTIONS

457

whelming number of flawless transactions, is a tes-

tament to the success of online auctioning. Never-

theless, some participants are disadvantaged by unde-

sirable or fraudulent behaviour. Preventing such be-

haviour is a difficult task and existing solutions are

largely inadequate.

Buying items from online auctions is the same as

buying items anywhere online. A buyer cannot physi-

cally inspect the merchandise as in a “bricks and mor-

tar” store. The buyer is forced to rely on the item’s

description. Distances between buyers and sellers can

be vast. This makes it hard to police transactions that

go awry, especially when buyers and sellers cross po-

litical and cultural boundaries.

The best recommendation is caveat emptor. Don’t

deal with unknown sellers, or sellers who reside in

countries which do not have strict enforcement of in-

ternational commerce laws. Ensure that you thor-

oughly research the item you are bidding for.

REFERENCES

Franklin, M. and Reiter, M. (1996). The Design and Imple-

mentation of a Secure Auction Service, IEEE Trans-

actions on Software Engineering, vol. 22, 302-312.

Schwartz, J. and Dobrzynski, J. (2002). 3 men are charged

with fraud in 1,100 art auctions on eBay, in The New

York Times.

Shah, H., Joshi, N. and Wurman, P. (2002). Mining for Bid-

ding Strategies on eBay, in SIGKDD’2002 Workshop

on Web Mining for Usage Patterns and User Profiles.

Stubblebine, S. and Syverson, P. (1999). Fair On-line Auc-

tions Without Special Trusted Parties, in Proceed-

ings of Financial Cryptography 1999, vol. 1648 of

Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer-Verlag,

230-240.

Trevathan, J., Ghodosi, H. and Read, W. (2005). De-

sign Issues for Electronic Auctions, in Proceedings of

the 2nd International Conference on E-Business and

Telecommunication Networks (ICETE), 340-347.

Trevathan, J., Ghodosi, H. and Read, W. (2006). An

Anonymous and Secure Continuous Double Auction

Scheme, in Proceedings of the 39th International

Hawaii Conference on System Sciences (HICSS),

125(1-12).

Trevathan, J. and Read, W. (2005). Detecting Shill Bidding

in Online English Auctions, Technical Report, James

Cook University.

Trevathan, J. and Read, W. (2006). RAS: a system for sup-

porting research in online auctions, ACM Crossroads,

ed. 12.4, 23-30.

Viswanathan, K., Boyd, C. and Dawson, E. (2000). A

Three Phased Schema for Sealed Bid Auction System

Design, Proceedings of ACSIP 2000 - Australasian

Conference on Information Security and Privacy, vol.

1841 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer-

Verlag, 412-426.

Wang, W., Hidvegi, Z. and Whinston, A. (2002). Shill Bid-

ding in Multi-round Online Auctions, in Proceedings

of the 35th Hawaii International Conference on Sys-

tem Sciences (HICSS).

SECRYPT 2006 - INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON SECURITY AND CRYPTOGRAPHY

458