FUNCTIONAL AND NON-FUNCTIONAL APPLICATION

SOFTWARE REQUIREMENTS

Early Conflict Detection

Paulo Sérgio Muniz Silva, Leonardo Chwif

Centro Universitário FIEO - Campus Narciso, R. Narciso Sturlini, 883 Osasco 06018-903 SP Brazil

Keywords: Application functional requirements, Application non-functional requirements, Requirements conflict

analysis

Abstract: Usually, standard practices of application software development are only focused on functional

requirements. However, IS managers know that when they have an experienced development team,

typically systems break not because they do not meet functional requirements, but because some system

attributes, also known as non-functional requirements, such as performance, reliability, etc., are not

satisfied. One of the root causes of this failure is that non-functional requirements do not receive an

adequate attention, are not well understood and are not appropriately modeled. Furthermore, non-functional

requirements may present critical conflicts among them. This paper proposes a pragmatic method to help

the early detection of conflicts between the functional and the non-functional requirements of application

software.

1 INTRODUCTION

Typically, when we analyze software application

requirements, we do that almost exclusively from

the functional viewpoint. Nevertheless, there is

another and very important class of software

requirements: non-functional requirements, or

quality attributes, used to express some of the

constraints acting upon software system behavior

(e.g., reliability, performance, accuracy, etc.).

IS managers know that when they have an

expe

rienced software team and a rather controlled

process, typically systems break not because they do

not meet functional requirements, but because some

desired system non-functional requirements are not

satisfied. One of the root causes of this failure is that

these requirements usually do not receive an

appropriate tool support and are less well understood

than functional requirements (Mylopoulos,

1999)(Chung, 1995). To complicate matters, usually

non-functional requirements are contradictory or

have negative interference among them. For

example: let us suppose we have usability and

security as general non-functional requirements for

certain IS application. To meet the usability

requirement, one decides to share the available

stored information implemented as an access to all

databases. This decision clearly has a negative

influence on the security attribute.

Pinned to this complex scenario is the important

i

ssue of the impact of functional requirements on the

non-functional ones. Typically, when system

analysts specify application functional requirements,

they do not analyze early in the project their impact

on non-functional requirements (obviously if the

latter are also specified). How can one relate the

functional requirements to the non-functional ones?

What are the negative impacts of the functional

requirements on the non-functional ones? This paper

proposes a pragmatic method to help the early

detection of conflicts between the functional and the

non-functional requirements, based on an

increasingly used software system functional

requirements model: the use case model (OMG,

2002). It is also based on a particular traceability

model using Rational Unified Process (IBM, 2002)

software requirements artifacts. Section 2 presents a

synthetic view of functional and non-functional

requirements and summarizes well-founded models

for representing and analyzing them. Section 3

proposes a method to the early detection of conflicts

between functional requirements and non-functional

ones. Section 4 shows a simple example to describe

and illustrate the method. Section 5 draws some

conclusions and presents the ongoing research.

343

Sérgio Muniz Silva P. and Chwif L. (2005).

FUNCTIONAL AND NON-FUNCTIONAL APPLICATION SOFTWARE REQUIREMENTS - Early Conflict Detection.

In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, pages 343-348

DOI: 10.5220/0002546803430348

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 FUNCTIONAL AND NON-

FUNCTIONAL REQUIREMENTS

Application requirement is an overloaded notion,

crossing various levels of abstraction. A convenient

road map, which helps the understanding of what

requirements we are dealing with, is presented in

(Leffingwell, 2003). Application properties are

initially stated as a list of simple descriptions from

the stakeholders’ viewpoint. They are features, or

services, provided by the application that fulfils one

or more stakeholder’ needs. Features are general

requirements that must be refined into more specific

requirements to guide the construction of the

application: the software application requirements.

As an example of a feature we may have: “The

purchase system should provide purchase trend

information on product items”. As an example of

correspondent application requirements we may

have: “Configure purchase trend report on product

items” and “Compile purchase trend history of

product items based on the configuration parameters

of the purchase trend report on product items”. The

separation of requirements into needs, features and

application software, helps the requirements

management, providing a general model for

requirements traceability: from stakeholder’s needs

to application software requirements, via application

features.

On the other hand, application requirements can

be characterized as functional and non-functional

requirements. Functional requirements express the

expected system behavior, i.e. how the system

should react to particular inputs and how the system

should behave in particular situations. Non-

functional requirements are constraints on the

functional requirements, e.g., reliability,

performance, project costs, etc. Almost all practical

methods concerning requirements elicitation,

analysis, specification and validation deal with

functional requirements. Non-functional

requirements (NFRs) are far much lesser understood

than functional requirements (FRs), in part because

they are intertwined (NFRs are always related to

some FR), or because some NFRs exert negative

influences on others, leading to conflicts. NFRs

studies and characterizations originated in technical

works on software quality metrics, e.g. (Boehm,

1996). But despite their vital nature, the predominant

state of practice does not provide guidelines

allowing requirement analysts to reason about NFRs

and the relations between FRs and NFRs.

On the FR side, a renowned method amidst the

plethora of application software requirements

elicitation methods is the use case model (OMG,

2002). The fundamental elements of the use case

model are: actor, use case and association between

an actor and a use case. An actor is an external entity

– human or system – with a specific role that

interacts with the system under consideration. A use

case is the description of the functional use of the

system from the actor’s (actors’) viewpoint: the

system must deliver a result with a measurable value

to actors. An actor-use case association denotes the

interaction between an actor and a use case. There

are some well-established use case model

specification templates, e.g. (IBM, 2002), allowing

the refinement of functional application software

requirements expressed as sequence of interactions

between actors and use cases. Use cases have also a

visual model – the use case diagram -, which is very

convenient to show the whole picture. However, the

use case model is not appropriate to state application

features, it is a model of application requirements.

(IBM, 2002) has another artifact to record

application features: the Vision document. The

Vision document defines the scope of the application

from the product point of view and is produced as an

outcome of stakeholders’ negotiation. There are

specific sections to define stakeholders’ and users’

needs, and product features as well.

On the NFR side, the use case model is not

adequate to state NFRs, not only because it does not

model and organize NFRs, but also because it is

error prone if NFRs are applicable to multiple use

cases (Supakkul, 2004). The Supplementary

Specification (IBM, 2002) only records NFRs as

declarative textual sentences. On the other hand,

there is a very promising alternative approach that

tries to rationalize the development process in terms

of non-functional requirements, providing ways to

reason about the NFRs and their relationships: the

NFR Framework (Chung, 1995) (Chung, 2000). This

approach is far from being known as use cases are,

but provides a unified framework to specify NFRs as

“first-class citizens” in requirements context.

We will present the NFR framework by quoting

(Supakkul, 2004) extensively. The framework is

goal-oriented, where NFRs are represented as

“softgoals” that must be satisfied where there is

sufficient positive and little negative evidence for

the claim. In fact, softgoals are “satisficed”, a term

coined to refer solutions that are sufficiently good,

even if they may not be optimal (Chung, 1995). The

“satisficeability” is determined by considering

design alternatives or decisions, analysing design

tradeoffs, recording the design rationale and

choosing design decisions. This rationale is

modelled in a softgoal interdependency graph (SIG),

representing softgoal decompositions. The selected

design decisions are used to guide application

architecture and design. Figure 1 depicts a SIG

fragment of Confidentiality softgoal. The light cloud

ICEIS 2005 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

344

denotes an NFR softgoal, with a label Type [Topic],

where Type is an NFR aspect (e.g. Confidentiality),

and Topic is the context for the softgoal (e.g.

Supplier). There are two forms of decomposition:

AND-decomposition (a single arc crossing

decomposition edges) and OR-decomposition (a

double arc crossing decomposition edges). Arrows,

carrying positive or negative contribution, represent

interdependencies between pairs of softgoals (not

depicted in the figure). A simplified version of the

framework expresses the degree of satisficeability

by a +/- indicator. The degree of the contribution to

the satisficeability is subjectively denoted as highly

positive (a ++ symbol), somewhat positive (a +

symbol), somewhat negative (a – symbol) or highly

negative (a – symbol). There is much more to be

said about the framework and its rich set of elements

and semantics, but in the present paper we will use

their minimum elementary elements.

3 CONFLICT DETECTION

In the early stages of application software

specification it is important to have a reasonable

knowledge about the impacts of FRs on NFRs. FRs

are often in conflict with NFRs and/or cause

undesirable scenarios that violate NFR requirements,

due to negative interdependencies between NFR

softgoals. We propose a pragmatic method that helps

the initial negative impact detection of FRs on

NFRs, focused on the interdependencies between

NFRs and based on an instance of the Rational

Unified Process (IBM, 2002) requirements

discipline guidelines. The method does not deal with

conflict resolution, and it is limited to conflict

detection in early stages of requirements analysis.

The method uses the Use Case Model as a model

for FRs and a simplified version of the NFR

Framework as a model for NFRs, focused on the

requirements viewpoint exclusively. The main

strategy of the NFR Framework relates design

decisions (also called as operationalizing softgoals)

with NFR softgoals, analyzing the impacts of the

former on the latter (Chung, 2000). This strategy

takes NFRs softgoals interdependencies into

consideration. Our strategy substitutes the role of

FRs for the role of design decisions, raising the level

of abstraction to the requirements viewpoint. The

strategy is based on the process of integrating NFRs

with FRs described in (Suppakul, 2004), but differs

from it in two important ways: it does not consider

design decisions and it brings NFRs

interdependencies into the front scene. The idea is to

analyze how FRs are related to NFR softgoals

having negative influences on other NFR softgoals.

This situation may characterize serious conflicts

derived from requirements (FRs and NFRs) solely.

Briefly, the method has two goals: to show the

relations between FRs and NFRs, and to show the

negative impacts of FRs on NFRs.

How to relate FRs to NFRs? (Supakkul, 2004)

presents the guidelines to relate a use case model to

NFRs. The integration is based on NFR association

points. In a use case model, the association points

are: Actor Association Point (external entity related

NFR, e.g. scalability: the system must handle

potentially large number of users); Use Case

Association Point (function related NFRs, e.g. fast

response time NFR to Withdraw Fund use case of an

ATM system); Actor-Use Case Association Point

(NFRs related to system access, e.g. security); and

System Boundary Association Point (NFRs that

affect the whole system).

Confidentiality

[Supplier]

[Supplier

identity]

[Supplier

proposals]

Confidentiality

[Supplier]

[Supplier

identity]

[Supplier

proposals]

Figure 1 - A SIG Fragment

Figure 1: A SIG Fragment.

Our method uses the same steps of (Supakkul,

2004) to identify the use case model related NFRs

and produce the SIG for identified NFRs. We

introduce steps to show NFR interdependencies and

relate the use case model to the NFRs, instead of

considering design and implementation issues as

(Supakkul, 2004) does. How to relate use cases to

NFRs softgoals? We will the use a particular

traceability model based on (Leffingwell, 2003),

which describes a very pragmatic traceability model

presenting the following tracing dependencies within

the requirements definition scope and from the RUP

viewpoint: product features traces to stakeholders’

needs; use cases traces to product features; and

supplementary requirements traces to product

features. As mentioned in section 2, the Vision

document defines stakeholders’ needs and product

features, the Use Case Specifications define the use

cases, and the Supplementary Specification declares

the NFRs. The tracing dependencies are recorded

into traceability matrices. It is worth noting that

product features are the pivotal element that links

use cases (FRs) to NFRs. We describe the proposed

method along the presentation of an illustration

example.

FUNCTIONAL AND NON-FUNCTIONAL APPLICATION SOFTWARE REQUIREMENTS: Early Conflict Detection

345

4 AN ILLUSTRATION EXAMPLE

Due to space limitations, we will describe and

illustrate our proposed approach with a very simple

example based on a hypothetic version of a pricing

system developed for major airlines described in

(Supakkul, 2004). We extensively quote (Supakkul,

2004) for the system general description and

adequately modify the requirements model to meet

RUP guidelines.

The pricing system allows the airlines to

collaborate with its suppliers over the Internet to

manage prices charged by suppliers for in-flight

service items such as meals, drinks, supplies, and

cleaning activity. In the use case model, the actor

Service Item Planner represents authorized airlines

users to manage the service items specification.

When service items specifications are created,

deleted or updated, the system automatically sends

electronic Request for Proposal (RFP) over the

Internet to the suppliers. The suppliers receiving the

RFP send price proposals to the airports they serve.

The airlines’ Procurement Manager then approves or

rejects the proposal. Suppliers revise the rejected

proposals and re-submit until both sides agree on the

prices. We will extend this general description with

the following requirement: there is a categorization

of suppliers with respect to service items, based on

their proposals’ history (price, quality, etc.). The

remaining of this section succinctly presents the

steps of the proposed method.

Step 1. Collect the application feature list from

the Vision document. The Vision document written

for the first release of application software product

produced the following high priority feature list:

1. Create/delete/update service item.

2. Update bill of materials.

3. Fill in RFP.

4. Group items with respect to category of

suppliers.

5. Maintain suppliers’ proposals history

6. Automatic sending of RFPs via Internet.

7. Submit proposals via Internet

8. Compose proposals for easy comparison

9. Approve/reject proposal.

10. Install application in supplier’s facilities.

11. Multi-language support to international

suppliers.

12. User-friendly help on-line.

13. Technical support to clients.

14. Custom user input/output due to cultural

business issues.

15. Localized user input/output.

Step 2. Analyze the use case specifications and

produce the Use Case vs. Feature Traceability

Matrix.

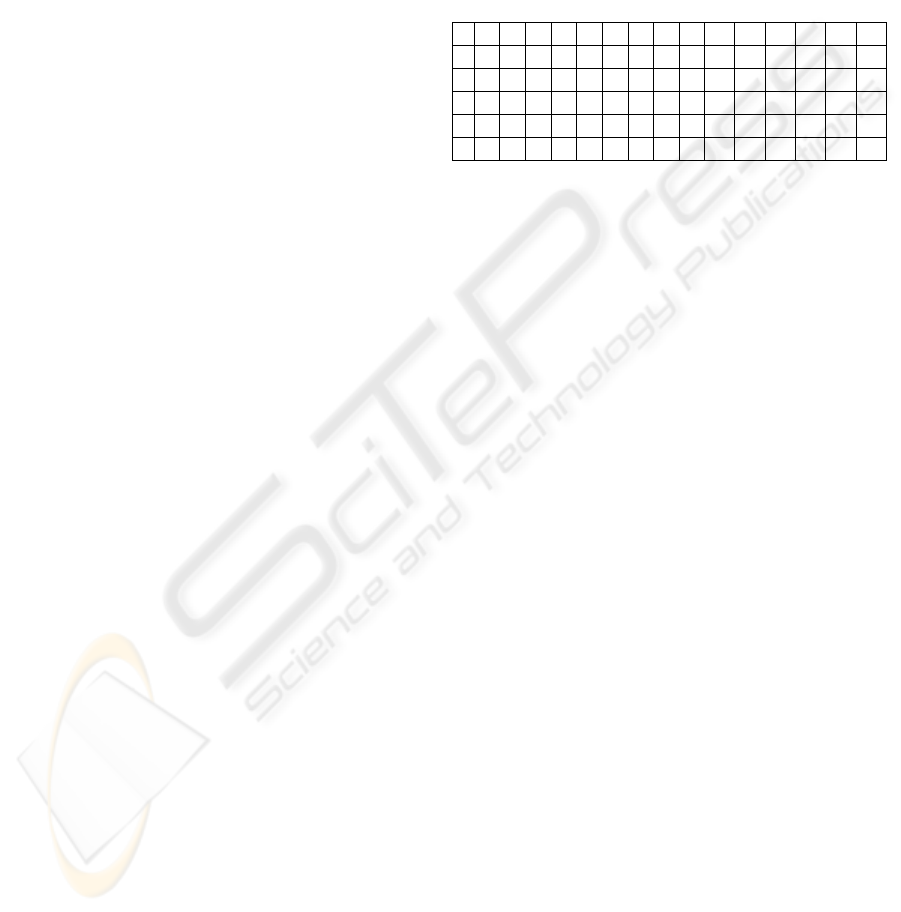

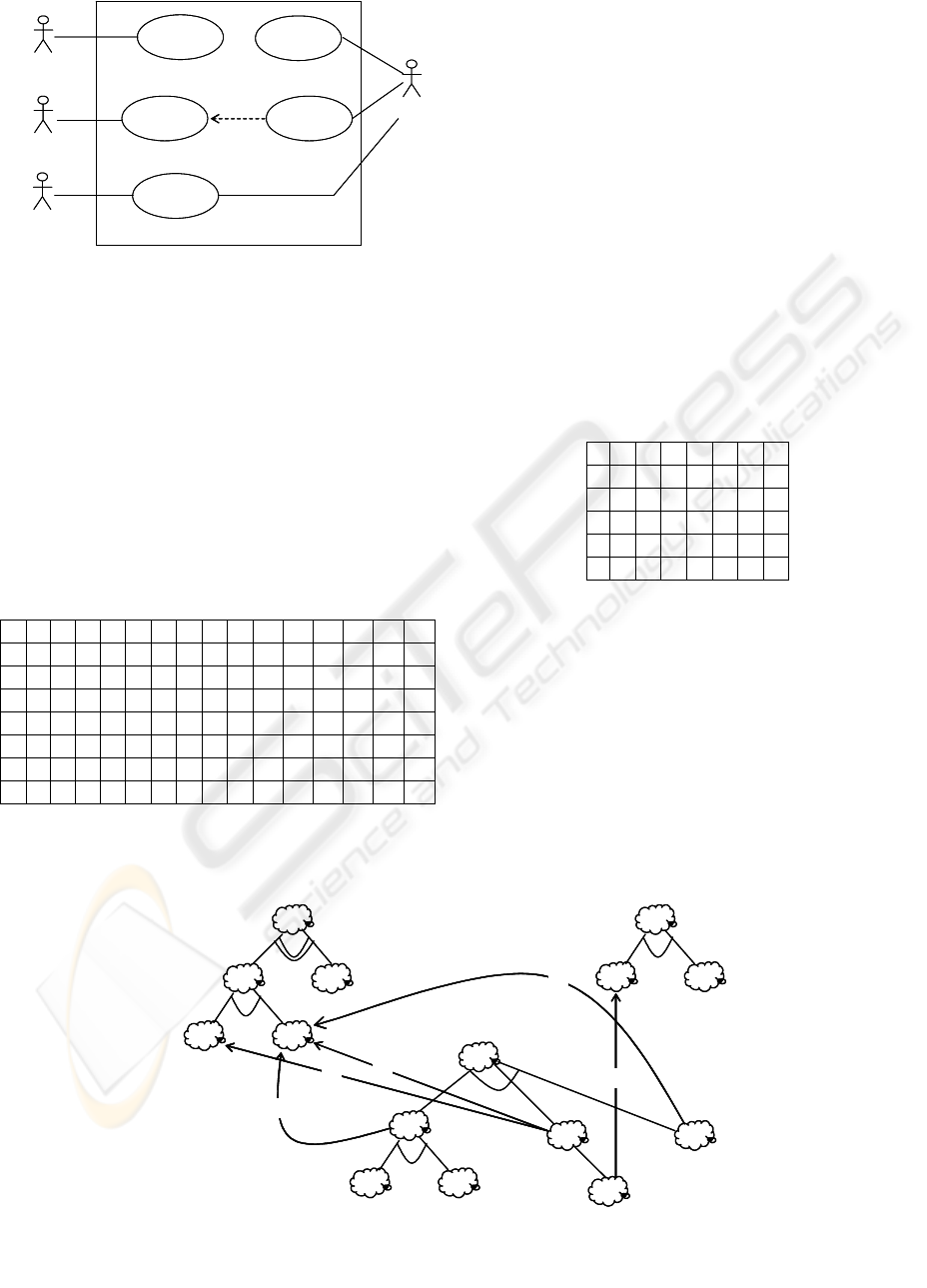

The use case model, depicted in Figure 2, is

straightforward and based on (Supakkul, 2004).

Table 1 shows the traceability matrix, relating use

cases (rows) and features (columns). This is a

Boolean matrix (Kolman, 1996), where the ‘X’ mark

denotes the Boolean value “true”. The blank cells

denote the Boolean value “false”.

Table 1: Use Case vs. Feature Traceability Matrix.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

1 X

2X XX

3 X X X X X X X

4 X X X X X X X X

5 X X X X X X X X

Step 3. Elaborate the NFR model.

The Supplementary Specification defined the

following NFRs, similar to (Supakkul, 2004):

Usability, meaning User Friendliness especially for

international suppliers; Serviceability, meaning

minimum client side support; and Confidentiality,

meaning that suppliers should not see each other’s

proposals and approvals. Serviceability has global

scope, ranging over the entire system; User

Friendliness impacts on suppliers’ interactions with

the system; and Confidentiality affects suppliers’

RFPs and proposals handling.

The simple and not complete SIG graph, for

illustration purposes only, is depicted in Figure 3. It

is also based on (Supakkul, 2004), differing from it

with respect to some decomposition details and

because we do not consider operationalizations (a

design viewpoint) at this early stage of the lifecycle,

but NFR decompositions exclusively. Our SIG graph

also depicts interdependencies between some pairs

of NFRs sub-goals. We may arrive at the following

(incomplete) interdependency relationships:

• Localized Input/Output may have a somewhat

negative influence on Technical Support, if

users do not adequately handle it.

• Customized Input/Output has a strong negative

influence on Installation and Technical Support,

for obvious reasons.

• Easily Accessible Help has a somewhat positive

influence on Technical Support, due to Help

lack of clarity or incompleteness.

• Identification, from User Friendliness, has a

strong negative influence on Confidentiality of

suppliers’ proposals (e.g., a supplier may enter

another supplier identity and have access to its

proposals).

ICEIS 2005 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

346

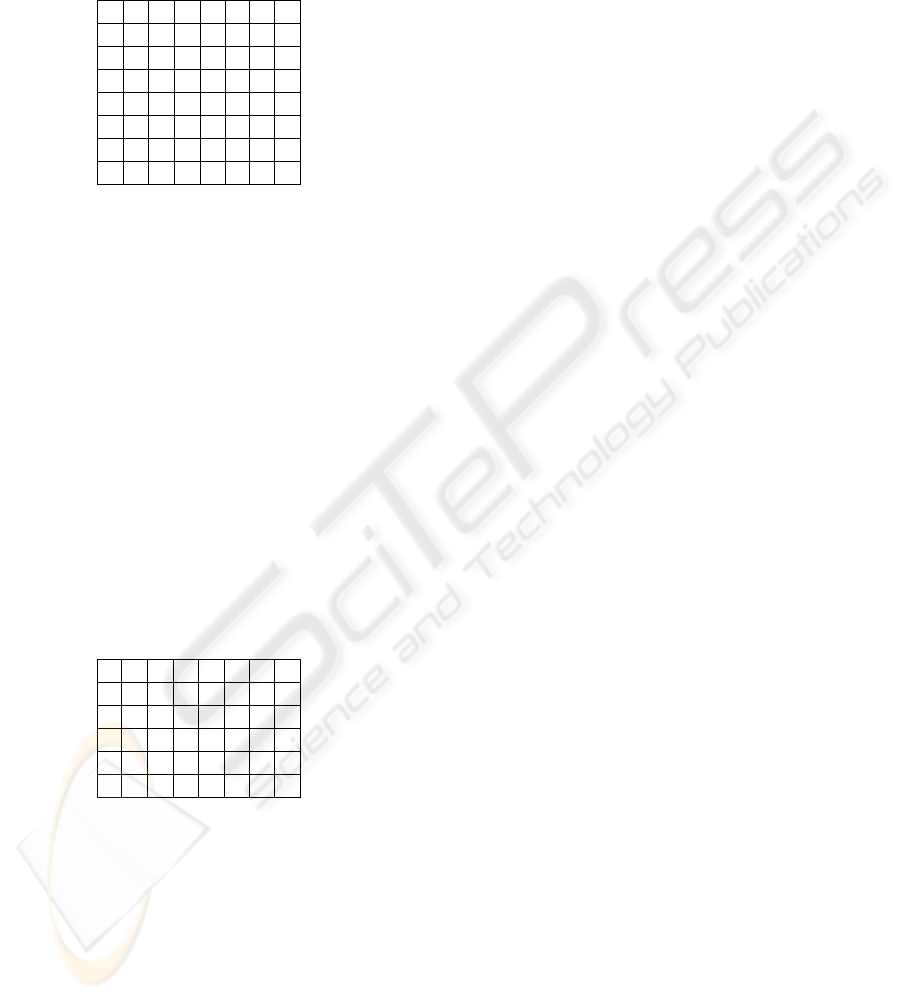

Step 4. Analyze the NFR Model and produce the

NFR vs. Feature Traceability Matrix.

After analyzing the NFR model, produce the

traceability matrix (also a Boolean matrix), depicted

in Table 2, that shows the relations between NFRs

(rows) and features (columns). NFRs are identified

as follows: S for Serviceability, C for

Confidentiality and U for User Friendliness. The

matrix also conveys the information about the

interdependency influences, having features as

pivotal elements as described in section 3 and values

of influences taken from the NFR model.

Table 2: NFR vs. Feature Traceability Matrix.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

N X

T X

P X X X X

D X

L X

C X

H X X

In the table, NFR N stands for Installation

softgoal, T for Technical Support softgoal, P for

Confidentiality of Supplier Proposals softgoal, D for

Confidentiality of Supplier Identity softgoal, L for

Localized Input/Output softgoal, C for Customized

Input/Output softgoal, and H for Easily Accessible

Help softgoal.

1. Update Bill of Material

BOM System

Service Item

Planner

2. Manage Service Item

5. Submit Proposal

«extend»

[posting RFP]

Supplier

4. Approve Supplier Proposal

Procurement

Manager

3. Send RFP

1. Update Bill of Material

BOM System

Service Item

Planner

2. Manage Service Item

5. Submit Proposal

«extend»

[posting RFP]

Supplier

4. Approve Supplier Proposal

Procurement

Manager

3. Send RFP

Step 5. Produce the Use Case vs. NFR

Traceability Matrix.

This matrix results from the Boolean product

(Kolman, 1996) of the matrices produced in steps 2

and 4. More formally, let A denote the Use Case vs.

Feature Traceability Matrix, let B denote the NFR

vs. Feature Traceability Matrix, and let C denote the

Use Case vs. NFR Traceability Matrix. We have:

Figure 2 - Use Case Diagram of the Example

C = A

⎜ B

T

,

where

⎜ denotes the Boolean product, and B

T

denotes the transpose of B. We need the latter in

order to interchange the rows and columns of B to

perform the Boolean product operation.

N T P D L C H

1

2

3 X X X X X X

4 X X X X X X

5 X X X X X X

This matrix shows that the specifications of Send

RFP, Approve Supplier Proposal and Submit

Proposal use cases must take applicable NFR

requirements into consideration.

Step 6. Produce the NFR Negative

Interdependency Matrix.

This matrix denotes the negative

interdependencies between pairs of NFRs depicted

in the SIG from the NFR Model. As we are only

interested in a qualitative evaluation of the negative

impacts of use cases (FRs) on NFRs, we will not

record into this matrix the degrees of

Serviceability

[Pricing System]

Confidentiality

[Supplier]

[Supplier

identity]

[Supplier

proposals]

[Server components]

[Client components]

Installation

Technical Support

Localized

Input/Output

[Language]

[Date/Time]

User Friendliness

[Supplier access]

Customized

Input/Output

Easily accessible

help

Identification

--

--

--

+

-

Serviceability

[Pricing System]

Confidentiality

[Supplier]

[Supplier

identity]

[Supplier

proposals]

[Server components]

[Client components]

Installation

Technical Support

Localized

Input/Output

[Language]

[Date/Time]

User Friendliness

[Supplier access]

Customized

Input/Output

Easily accessible

help

Identification

--

--

--

+

-

Figure 3 - Softgoal Interdependency Graph of the Example

Figure 2: Use Case Diagram of the Example.

Figure 3: Softgoal Interdependency Graph of the Example.

FUNCTIONAL AND NON-FUNCTIONAL APPLICATION SOFTWARE REQUIREMENTS: Early Conflict Detection

347

‘satisficeability’, but simply a mark (e.g. ‘X’)

denoting the existence of a negative interdependency

between an NFR row element and an NFR column

element. As usual, we interpret the mark as the

Boolean value “true”, taking the produced matrix as

a Boolean matrix.

N T P D L C H

N

T

P

D

L X

C X X X X

H

Step 7. Produce the Use Case vs. NFR Impact

Matrix.

This matrix results from the composition of the

Use Case vs. NFR Traceability Matrix and the NFR

Negative Interdependency Matrix, showing the

negative impacts of use cases on NFRs. More

formally, let E denote the Use Case vs. NFR Impact

Matrix, let D denote the NFR Negative

Interdependency Matrix, and let C denote the Use

Case vs. NFR Traceability Matrix as above. Both C

and D are Boolean matrices. In this case, the

composition of C and D, denoted by D Ε C, can be

computed by the Boolean product of C and D

(Kalman, 1996):

E = D Ε C = C

⎜ D.

We record a mark (e.g. ‘X’) to denote a negative

impact of a use case on an NFR. Computing the

composition of the NFR Negative Interdependency

Matrix and the Use Case vs. NFR Traceability

Matrix, we have the following matrix:

N T P D L C H

1

2

3 X X X X

4 X X X X

5 X X X X

This matrix shows that the specifications of use

cases Send RFP, Approve Supplier Proposal and

Submit Proposal must receive a special attention

during analysis, because they potentially conflict

Installation, Technical Support, Confidentiality of

Supplier Proposals, and Confidentiality of Supplier

Identity non-functional requirements.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper presented a method to help the early and

initial analysis of the relationships between

functional requirements and non-functional

requirements, and of the negative impacts, or

potential conflicts, between functional requirements

and non-functional requirements. The presented

method is grounded in the use case model (OMG,

2002), in a general traceability model using Rational

Unified Process artifacts (Leffingwell, 2003), and in

the not so well known NFR Framework (Chung,

2000), providing a pragmatic approach to handle this

admittedly difficult tasks. The method is limited to

the detection of potential conflicts in early stages of

requirements elicitation and analysis.

Currently we are working on the following

goals: (1) the refinement of the integration of non-

functional requirements with functional

requirements, to capture a more detailed view of

their relationships and to develop a consistent

traceability model; (2) the integration of the degrees

of ‘satisficeability’ between softgoals in our method;

(3) the analysis of commercial case tools that

propose requirements traceability and conflict

analysis with respect to the proposed approach.

REFERENCES

Boehm, B.W. and In H., 1996. Identifying quality-

requirements conflicts.

IEEE Software, March, 1996.

Chung, L., Nixon, B.A. and Yu, E., 1995. Using non-

functional requirements to systematically support

change. In

RE ’95, The Second IEEE International

Symposium on Requirements Engineering

. IEEE

Computer Press, pp. 132-139.

Chung, L. et al., 2000. Non-functional requirements in

software engineering. Boston: Kluwer Academic

Publishers.

IBM, 2002. IBM Rational Unified Process 2002.

Kolman, B., Busby, R.C. and Ross, S., 1996. Discrete

mathematical structures – 3

rd

. Edition. New Jersey:

Prentice-Hall.

Leffingwell, D. and Widrig, D., 2003. Managing software

requirements: Second Edition. USA: Addison-Wesley.

Myloupolos, J., Chung, L. and Yu, E., 1999. From object-

oriented to goal-oriented requirements analysis.

Communications of the ACM, 42(1), pp.31 – 37.

OMG, 2002. OMG Unified Modeling Language

Specification: version 1.5. Object Management Group,

MA, USA.

Supakkul, S. and Chung, L. Integrating FRs and NFRs: a

use case and goal driven approach. In

Proc. 2

nd

International Conference on Software Engineering

Research, Management and Applications (SERA ’04)

,

May 5 – 7, 2004, Los Angeles, CA, pp. 30–37.

ICEIS 2005 - INFORMATION SYSTEMS ANALYSIS AND SPECIFICATION

348