BUSINESS MODELLING THROUGH ROADMAPS

Judith Barrios A, Jonás Montilva C

Universidad de Los Andes, Facultad de Ingeniería,

Escuela de Ingeniería de Sistemas, Departamento de Computación,

Mérida, 5101, Venezuela

Keywords: Business Modelling, Enterprise Information Systems, Process Models, and Organisational Knowledge.

Abstract: Business modelling is a central activity to many different areas, including Business Process Reengineering,

Organisational Development, Enterprise Modelling & Integration, Business Process Management and

Enterprise Application Integration. It is well known that the business domain is not easy to understand

neither to represent even for specialised people. The success of most of the contemporary methods for

modelling Business Organisations is strongly associated with the level of understanding that the modelling

team can attain about the specific situation being modelled. This understanding is directly related with the

degree of modelling experience that the team has, as well as their ability to work with the techniques and

tools prescribed by a specific method. Nowadays, most of the existing business modelling methods is

concentrated in what the business concepts are and how to represent them. But, they lack of process

guidance, which is needed to help the team through the modelling process. We elaborated the method BMM

for modelling business application domains that provides working guidelines for the modelling team. This

method, based on method engineering concepts helps teams to, not only, get a comprehensive knowledge

about the business domain being modelled, but also, about the process of modelling the domain itself. This

paper concerns with the representation of the process of modelling a business by using decision oriented

process model formalism. The main contribution of our work is a set of roadmaps that contains the

knowledge associated with team member’s modelling experience in business modelling and EIS

development. This knowledge arises from several case studies.

1 INTRODUCTION

Business modelling is a central activity to many

different areas, including Business Process

Reengineering, Organisational Development,

Enterprise Modelling & Integration, Business

Process Management, Enterprise Application

Integration, ERP System Configuration, E-

Commerce, Software Development and Information

System (IS) Planning and Development. For

instance, authors, such as Avison, Fitzgerald

(Avison, 2003) and Flynn (Flynn, 1992) emphasise

the importance of modelling the application domain,

i.e. the business organisation, before eliciting IS

requirements. A business model – a model of the

Enterprise IS application domain - can help IS

developers to gain a more comprehensive

understanding of the business, its information

problems, and the functional requirements that the

IS must satisfy.

The success of most of the contemporary methods

for modelling business organisations is strongly

associated with the level of understanding that the

modelling team has or can achieve about the specific

situation being modelled. This understanding is

directly related with the degree of modelling

experience that team members have as well as the

abilities, they have working with the techniques and

tools specified for the method. A good method

should help teams acquiring experience and tools

abilities by providing them with working directives

that they can use while they are modelling.

Until now, method use and success are rigorously

associated to team leader experience. That is, all

his/her experience about how to manage specific

modelling situations or projects is acquired from

working in many projects and applying many times

348

Barrios A. J. and Montilva C J. (2004).

BUSINESS MODELLING THROUGH ROADMAPS.

In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Enter prise Information Systems, pages 348-355

DOI: 10.5220/0002611803480355

Copyright

c

SciTePress

the same method. Experience it’s just an individual

knowledge that only belongs to the team leader. Any

other person in the organisation can not reuse this

knowledge. Reusing is a paradigm that allows

organisation to take advantage of its previous

experience, not only to gain time and money but to

get things done better.

Nowadays, most of the existing business modelling

methods lack of this kind of guidelines. Some of the

methods found in the literature are Business

Engineering (Taylor, 1995), RUP (Krutchen, 2000),

Watch (Montilva et al., 2000), MERISE

(Piattini,1995), EKD (Bubenko, 1994), Mainstream

Objects (Yourdon et al., 1995), Information

Engineering (Martin et al., 1994), Business

Modelling with UML (Eriksson et al., 2000), and

Enterprise Modelling with UML (Marshall, 2000).

They just describe, in one way or another, the

activities, artefacts and workflow that are needed to

model a business. Nevertheless, none of them

considers and models the process of modelling a

business itself. In other words, they do not give

explicit details and guidelines related with the how

and when building each one of the elements or

artefacts representing a particular business domain;

i.e. about the process model associated to the

method. We consider that, to guide a process is not

just to prescribe a set of steps to be followed or to

define a set of activities that must be done in a

certain order. To guide a process involves the

situational definition of what, when, how and under

what circumstances a modelling activity could be

done.

In (Montilva et al., 2003) we introduce a business

modelling method called BMM (Business Modelling

Method) that captures and represents the main

concepts of a business system and their

relationships, including the technologies that are

applied by the business system. According to

method engineering concepts, BMM has three main

components– the product model, the process model,

and the team model. The first component has already

been described in the referred paper; here we will

concentrate our effort in describing the second one,

i.e. the process model. Thus, this paper concerns

with the representation of the process of modelling

business by using BMM method. The process model

is situational oriented and it is represented at the

higher level by a roadmap. A roadmap is based on a

set of modelling intentions related by modelling

strategies. It also contains a set of modelling routes

which describe specific sequences of the execution

of map intentions. Each route expresses a way of

working defined and followed for modelling a

particular business context. A map route may be

selected, reused and modified by a modelling team

in a similar modelling context. Situational oriented

process models permit to model a business from

reusing previous modelling experience or even the

experience coming from outside the organisation.

The paper is organised as follows. In Section 2, we

present the working definition of business systems

used by the BMM method and the relationships

between the notions of enterprise, business systems,

and enterprise information system. The scope and

structure of the BMM method are summarised in

Section 3. Section 4 presents the process model

along with its background concepts. Section 5

presents an example of how to use the process

model, i.e. how to navigate in a roadmap. Finally,

section 6 discusses the significance of the process

model, its advantages and limitations.

2 THE BUSINESS SYSTEM

An enterprise is a business organisation that may be

seen as a human activity system whose main

activities, called business processes, are designed

and executed to reach a set of pre-defined goals

(Fuenmayor, 2001). A business system is part of a

major system: the enterprise. A production

enterprise, for example, is structured into several

business systems, such as the engineering system,

the production system, the marketing system, the

personnel system, the finance system, and the

accounting system. The execution of the enterprise’s

business processes is normally supported by a kind

of software applications called Enterprise

Information Systems (EISs). Some common types of

EISs are enterprise resource planning (ERP), legacy

applications, OLTP applications, EAI applications,

e-business systems, e-commerce applications,

management information systems, and executive

information systems.

Enterprise Information Systems

Business

Processes

Business

Rules

Business

Objects

Goals

Events

Actors

achieve

regulate

trigger

involve

perform

supply

information

Data Objects

model

update

data

objects

update

data

objects

request

information

change

state

Business System

Enterprise

Figure 1: Relationships between an enterprise, its business

systems and its EISs

BUSINESS MODELLING THROUGH ROADMAPS

349

A business system is comprised by an organised set

of activities called business processes that are

designed and performed by a group of actors with

the purpose of achieving a set of pre-defined goals.

Actors are organised into a job structure composed

by business units (e.g. departments, divisions, and

sections). Actors have associated roles that define

the responsibilities for performing processes. Each

processes requires, uses or involves a set of business

objects (e.g., personnel, clients, raw materials,

products and clients) and one or more technologies

(e.g., information systems, production methods,

techniques or instruments). A business process is

triggered by an event (e.g., the arrival of raw

material or a service order) which may modify the

state of the objects involved in the process. A

process is regulated by business rules (e.g. laws,

policies, norms and procedures). Therefore, an

enterprise is seen as a set of business systems. Each

business system has associated one or more EISs, as

shown in Figure 1.

The tight relationships between a business system

(goals and processes levels) and its EISs illustrated

in Figure 1 can be summarised as follow: “Actors

request information from an EIS to perform business

processes. The EIS supply the requested information

by processing the data stored in its database. An EIS

database is a model of the business objects

associated with the business processes. Each

relevant object of the business system is represented

in the database by a data object, which captures the

state and behaviour that the business object has in

the business system at a given time. The business

processes and the events that occur in the business

system, or in its environment, generate data that are

used by the EIS to update the database”.

3 THE BUSINESS MODELLING

METHOD (BMM): Scope And

Components

The BMM method for business modelling uses the

notion of business system developed in Section 2, in

order to create business models. The BMM is based

on principles, processes and concepts borrowed from

Method Engineering (Odell, 1996), (Brinkkemper,

1996), Enterprise Modelling (Eriksson et al., 2000),

(Marshall, 2000), (Montilva, 1999), and Object

Oriented Software Engineering (Bruegge, 2000).

From the point of view of method engineering, a

method must be composed of three interrelated

components: a product model, a process model and a

team model. The product model describes the

generic structure and characteristics of the product to

be elaborated using the method. The process model

describes the structure and dynamics of the activities

needed to produce the product; and the team model

describes the roles of the team’s members to be

played during the application of the method

(Montilva, 2003). BMM is structured as follows:

a. The BMM product model. It describes the

generic concepts that characterise any business

system and the relationships between these

concepts. It defines the structure of the business

model and indicates what must be captured and

represented during the business modelling

process.

b. The BMM team model. It describes an

appropriated way of organising the business

modelling team and describes the roles that the

members of this team must play during the

business modelling process.

c. The BMM process model. It describes

modelling intentions along with a set of

guidelines that guide modelling team through the

process of building a business model. This

business model is an instantiation of the product

model concepts.

The first two components are briefly described in the

next subsections. The process model will be

described in detail in section 4.

3.1 The Product Model

Based on the notion of business system elaborated in

Section 2, we built a product model that identifies

and represents the set of generic concepts that may

be found in any business system (see Figure 1). The

importance of this model is that it identifies the set

of business concepts that must be represented during

the process of modelling the business system. An

important decision to be made during the business

modelling process is the notations and languages

that the modelling team must use to represent the

structure and behaviour of the business concepts.

We chose UML (Booch et al., 1999) as the main

modelling language. UML is the de facto standard

for modelling software and is used by many well-

known methods involving business modelling (see,

for example (Krutchen, 2000), (Eriksson et al.,

2000), (Marshall, 2000). The main business concepts

manipulated by our method are: Business goals,

business processes, actors, business units,

technologies, business rules, business objects, and

events. For further details about the product model,

see (Montilva et al., 2003).

ICEIS 2004 - DATABASES AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS INTEGRATION

350

3.2 The Team Model

An important element of any method is the

organisation of the team that will develop the

product. Defining the roles of the team members is

crucial to the application of the process model,

because it helps the team leader to select the right

people and assign the appropriate activities to them.

A business modelling team can be organised in

many different ways depending on the size and

complexity of the business system. For instance, for

small and medium size projects, the business

modelling team can be organised by a team leader

who is responsible for planning, organising,

directing, and controlling the effort and resources

needed to model the business system; one or more

adviser users that bring to the modelling process

their knowledge about the business system; one or

more business analysts who interpret the user’s

knowledge and represent this knowledge using the

modelling languages indicated in the product model.

Business analysts are responsible for building the

components of a business model; and, one or more

business system managers who are responsible for

validating the business model.

4 THE PROCESS MODEL

A process model prescribes the set of possibilities

for manipulating and relating the concepts described

in the product model, in order to build a product – a

business model. A process model should guide the

modelling team while they are building a business

model. For instance, the hierarchy of goals

representing the future situation of a public

organisation is a product built by using product

model concepts according to process model

prescriptions and guidelines. The guidelines allows

team members to select, according to current

business and modelling situations, what are the

intentions associated to goals hierarchy that best

match the current modelling situation.

Commonly, process models associated to business

modelling methods are activity oriented. They

organise modelling activities in different ways. It

could be for example, a set modelling phases, a set

of steps to be followed or even a cyclic iterative

process. However, the fact of prescribing a strict set

of sequential activities that should be followed, one

after another, limits the application scope of

designer knowledge and experience. Consequently,

listing activities and tasks restricts the selection of

what activity is more appropriated to solve a

particular modelling problem or what should be the

precedence order of these activities. Summarising,

an activity oriented process model restricts the

creativity that should be present in any design

process.

BMM process model inspired on the intention

oriented paradigm described in (Jarke et al., 1999) is

presented as process maps that contain multiples

roads for building any of the business products listed

in section 3. In our case, an intention expresses a

current or a future modelling state, a vision or future

modelling direction to be followed. Usually, it is

expressed as a verb that expresses an action to be

executed over a subject. For instance, “Build IS

model” is a modelling intention.

The intention-oriented formalism allows us to

express, directly, the modelling intentions associated

with business model construction. Each time that an

intention is executed as a consequence of a decision,

the current modelling situation is transformed into

another situation. This new situation is submitted to

a new decision process that will allow modeller to

transform the current state of the product being built,

and so on. This way of working characterises

decision oriented process models, it allows us to

define non-deterministic process models expressed

at different levels of granularity.

Finally, the BMM process model represent directly

team modelling intentions (which are based on

current and future modelling situations) without

restricting and encapsulating his/her creativity,

knowledge and experience. The intention oriented

process model formalisation is carefully described in

(Rolland et al., 1999) and (Barrios, 2001).

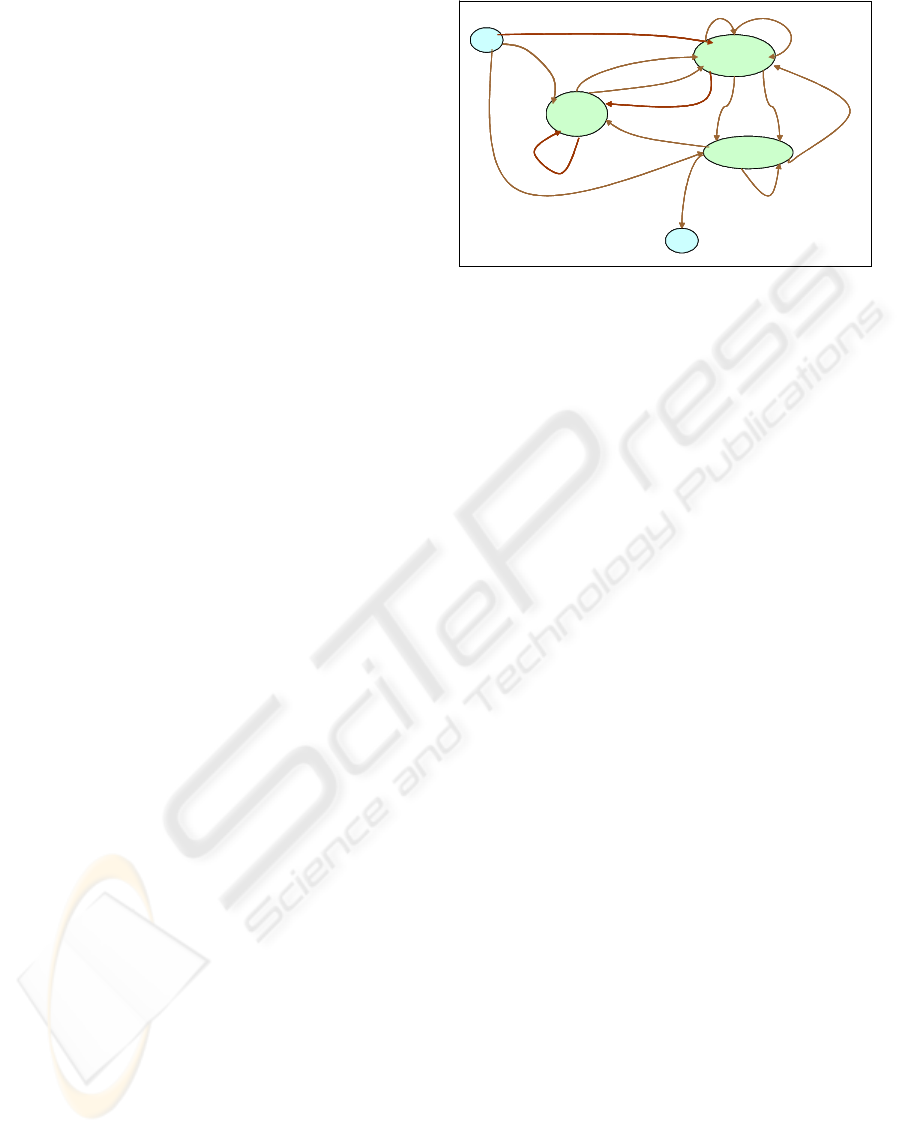

4.1 The roadmaps

A roadmap is a multi-process model that comprises

a set of modelling routes that can be followed to

build a particular product. We called roadmap

because its analogy with a traditional map of routes

where for going from one point to another may be

several different routes (see figure 2). By using a

roadmap, team members can see at a glance, the set

of possibilities they have for progressing in the

process of building a business model (or a part of it).

The selection of a specific route depends on what are

the current decider needs; i.e. taking into account the

current modelling situation and the team experience,

team members select what to do next and how to do

it. Observing figure 2, we note that each modelling

intention is a node in the map, each different way of

achieving an intention is a road between one

intention and another (an arc between two

BUSINESS MODELLING THROUGH ROADMAPS

351

intentions). A roadmap has always two fixed

intentions called Start and Stop. They represent the

intention to start navigating and to stop doing so,

respectively.

An intention oriented process model is organised

into three levels of abstraction, which allows us to

represent guidelines at different levels of detail. At

the two higher levels, the granularity of the

guidelines is gross, i.e. the intentions are expressed

by global verbs whose decomposition in low level

verbs is always possible. At these levels, the process

model is presented as process maps: a global map

for the higher level intentions and several local maps

according to the decomposition of each one of the

higher level intentions. Each process map may

contain multiple routes for building specific product

parts by following different modelling strategies

according to particular modelling situations. For

instance, the route followed in the study case

presented in section 5 is sequentially numbered

(steps 1 to 7) in the global depicted in figure 2.

At the lowest level, the guidelines are expressed by

contexts according to Nature Project (Jarke et al.,

1999). A context expresses a specific way of

achieving a specific intention according to a specific

strategy already chosen. A context may be a set of

steps to be executed in a particular order – it is

called a plan context, a set of alternative ways which

can be selected according to context directives – a

choice context. At the end of any of these two kinds

of context, there is always an executable context. It

prescribes, in detail, the set of actions needed to

achieve an intention. This set of actions is expressed

by adapting the notion of context that has been

conceptualised in the Nature Project according to

business model representation needs. For a more

detailed description of this formalisation review

(Barrios, 2001) and (Rolland et al., 1999).

4.1.1 Map Guidelines

As we explained above, a roadmap is a navigational

structure that supports the dynamic selection of the

next intention to be achieved along with the

appropriated strategy to execute it. A strategy

defines a particular way or approach of achieving an

intention. In order to facilitate decisions about what

intention will be next and which strategy is the most

appropriated, we use three types of guidelines

according to (Barrios, 2001). These guidelines or

directives provide the situational modelling support

needed to follow a process map: the Intention

Selection Directive (DSI) the Strategy Selection

Directive (DSS), and the Intention Execution

Directive (DAI). The DSI permits to progress in the

process of building a product by selecting the next

modelling intention. The DSS permits to select a

strategy for executing the modelling intention

already selected. The DAI describes the set of

activities and tasks that should be performed for

building the product according to the strategy

already selected.

The guidelines are expressed by considering a triplet

of concepts (Ii, If, S). Ii represents the initial

intention – associated to the current modelling

situation, If represents the final intention – next

intention to be executed, and S represents the

strategy that guides the way of passing from Ii to If.

Each directive comes along with a set of arguments

that help during the process of choosing a particular

intention to be achieved and the way it will be

achieved.

Due to space restrictions, in Table 1 there is an

example of each type of guideline. They are part of

the global map depicted in Figure 2.

Table 1: Examples of Roadmap Guidelines

DSI1

<(Business Modelling Problem) ; Progress from

Start> :=

<( Business Modelling Problem) ; Select (DAI9

: < (Business Modelling Problem) ; Build

Business Goal Model by following Analyst

Driven Strategy>) (A7) U

<( Business Modelling Problem) ; Select (DAI16

: < (Business Modelling Problem) ; Build

Information System Model by following EIS

strategy>) (A8) U

<( Business Modelling Problem) ; Select

(DAI1 : < (Business Modelling Problem) ;

Build Business Process Model by

following Analyst Driven strategy>) (A9)

DSS2

< (Business Goal Model) ; Progress to Build

Business Process Model >:=

<( Business Goal Model); Select ( DAI10 : <

(Business Goal Model) ; Build Business Process

Model by following an Chain Valued Strategy

>)> (A1) U

<( Business Goal Model); Select ( DAI19 :

< (Business Goal Model) ; Build Business

Process Model by following a Technology

based Strategy >)> (A2)

DAI1

6

<(Business Modelling Problem); Build

Information System Model by following an

EIS Strategy> : =

<( Business Modelling Problem) ; Determine IS

Domain > .

<( Business Modelling Problem, IS domain) ;

Revise IS initial requirements > .

<( Business Modelling Problem, IS domain,

revised list of requirements) ; Define IS Scope >

ICEIS 2004 - DATABASES AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS INTEGRATION

352

5 HOW TO NAVIGATE IN A

ROADMAP

In this section we will illustrate through an example,

the way roadmaps guide the process of doing

business modelling. First, we will characterise the

current modelling situation in order to establish the

set of parameters that should be taking into account

when deciding how to model a business. Then, we

will describe systematically how to select a new

modelling intention, the strategy to achieve it and

the consequences of making that selection. Consider

that each time that a decision is made, the current

situation is transformed into a new situation. This

new modelling situation is then submitted, through a

new process of decision to select an intention to

transforming it into a new situation. This process is

repeated again and again until the product part (or

the whole business model) is obtained.

Our case study takes place inside a public

organisation, highly dependent on government

regulations and country laws. Its initial need is to

build an integrated information system for

supporting the financial process of the organisation.

As we explained before, the process of modelling

begins in the “start” intention in figure 2. The

modelling problem described in the previous

paragraph take us to decide that the modelling

process must starts with the “Build Information

Systems Model” global intention. We see that there

is only one strategy to achieve it from the start

intention; that is the “EIS – Enterprise Information

System – strategy” (DAI16). In that particular case,

the decision is supported by the guideline DSI1,

which arguments match with the modelling problem

exposed in this section. Each guideline always has a

set of arguments that permits to make a decision

about which one of the alternatives is the most

appropriated for a specific modelling situation. For

instance, the argument associated to the “Build the

Information System Model” intention is A8. It

prescribes the existence of a specific information

system need inside an integrated work environment;

it assures that the list of the IS initial requirements,

already exist. In addition, it guaranties that there is

enough managing support and resources availability.

Thus, the modelling decision is to build an

information system model by following the EIS

strategy (1).

Once the scope of the Financial Information System

– FIS project is established, and keeping us at the

global map level (figure 2), the modelling team

passes to associate the IS local goals with the

business goals. This decision will permit to define an

information system that really helps to accomplish

the business goals and to assure that it is integrated

to the others IS already built in the organisation.

Therefore, the “Alignment Strategy” is followed for

achieving the “Build the Business Goals Model”

intention (2). This decision has been supported by

the DSI4 guideline.

Continuing with the modelling process, and

considering that the organisation is highly dependent

on government regulations and laws, the next

decision is associated to the intention “Build

Business Process Model” by following the

“Technology based Strategy” (3). This decision

takes us to, first, modelling business processes

according to business rules and business

technologies, and then, to model primary and

support processes. The object oriented and the

actor’s driven strategies are executed in order to

complete and validate business process model. They

are represented in the global map as steps (4) and

(5). A more detailed view of the process followed -

the route- to build the business process model is

depicted in the local map showed in figure 3. This

modelling route is a set of 13 steps numbered

sequentially.

After the business model is built and validated, the

modelling team can start to modelling system

requirements and to defining business objects to

achieve the intention “Build Information System

Model”. They are represented by steps (6) and (7) in

the global map.

It is important to mention that this modelling process

is iterative. That is, the selection and execution of a

specific set of intentions has been repeated many

times until the relationships between Business

Process and FIS were well understood, defined and

represented by the business model. Once the

business model is ready, the Financial Information

System FIS can be developed (8). The whole

modelling process ends with a “Completeness

Strategy” to achieve the “Stop” intention. These

decisions are supported by the guidelines DSI3,

DSS3, DSI4, and DSS4, respectively.

Build

Business

Goals

Model

Build Business

Process Model

Start

Stop

DAI 1: Analyst

Driven Strategy

DAI 2: Process

Clustering Strategy

DAI 9: Analyst

Driven strategy

DAI 8: Completeness

Strategy

DAI 15:

Validation

Strategy

DSI3

DSI1

DSI2

DAI10: Chain

Valued Strategy

Build Information

System Model

DAI 14: Object

Oriented Strategy

DAI 12:

Requirement

Strategy

DSS3

1

2

3

4

7

DAI 13: Actor

Driven Strategy

DAI 11: Object

Oriented Strategy

6

DAI 16: EIS

Strategy

DAI 17:

Alignment

Strategy

DAI 18:

Enterprise

Support

DAI 19:

Development

Strategy

DSI4

DAI19: Technology

based Strategy

9

5

8

DSS2

DSS4

Build

Business

Goals

Model

Build Business

Process Model

Start

Stop

DAI 1: Analyst

Driven Strategy

DAI 2: Process

Clustering Strategy

DAI 9: Analyst

Driven strategy

DAI 8: Completeness

Strategy

DAI 15:

Validation

Strategy

DSI3

DSI1

DSI2

DAI10: Chain

Valued Strategy

Build Information

System Model

DAI 14: Object

Oriented Strategy

DAI 12:

Requirement

Strategy

DSS3

1

2

3

4

7

DAI 13: Actor

Driven Strategy

DAI 11: Object

Oriented Strategy

6

DAI 16: EIS

Strategy

DAI 17:

Alignment

Strategy

DAI 18:

Enterprise

Support

DAI 19:

Development

Strategy

DSI4

DAI19: Technology

based Strategy

9

5

8

DSS2

Build

Business

Goals

Model

Build

Business

Goals

Model

Build Business

Process Model

Build Business

Process Model

StartStart

StopStop

DAI 1: Analyst

Driven Strategy

DAI 2: Process

Clustering Strategy

DAI 9: Analyst

Driven strategy

DAI 8: Completeness

Strategy

DAI 15:

Validation

Strategy

DSI3

DSI1

DSI2

DAI10: Chain

Valued Strategy

Build Information

System Model

Build Information

System Model

DAI 14: Object

Oriented Strategy

DAI 12:

Requirement

Strategy

DSS3

1

2

3

4

7

DAI 13: Actor

Driven Strategy

DAI 11: Object

Oriented Strategy

6

DAI 16: EIS

Strategy

DAI 17:

Alignment

Strategy

DAI 18:

Enterprise

Support

DAI 19:

Development

Strategy

DSI4

DAI19: Technology

based Strategy

9

5

8

DSS2

DSS4

Figure 2: The BMM Global Roadmap

BUSINESS MODELLING THROUGH ROADMAPS

353

Finally, it is important to mention that for really take

advantage of this notation, team members must

remember that: a DSI guides the selection of the

next intention to be achieved from a certain

departing intention; a DSS guides the decision about

which is the most appropriated strategy to achieve

the intention already selected; and a DAI guides, in

precisely manner, the execution of the selected

intention with the selected strategy.

Figure 3: The Local Roadmap for “Build the Business

Process Model” intention

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

We have presented in this paper the process model –

the roadmap of the business modelling method

called BMM. This method helps business modelling

teams to plan, organise, and control the process of

modelling a business organisation. BMM provides a

clear and precise definition of the enterprise as a

system. A system view of the enterprise helps

organisational members to get a wider and complete

picture of the enterprise, its components, and their

relationships.

The process model of the BMM, not only guides the

business modelling team to get an understanding of

a business system they are modelling, but to get a

comprehensive knowledge about the process of

modelling the business itself. This knowledge is

formalised through a roadmap containing strategies

for achieving typical business modelling intentions.

This formalisation permits to express, select, update

and reuse experience about the process of modelling

business context with BMM. This knowledge is very

useful for team modellers that do not have enough

experience about BMM, when they are modelling

similar business contexts in the same organisation or

in other ones.

The significance and contribution of our process

model are summarised as follows:

• A roadmap provides a global view of what has to

be done for building a business model.

• A roadmap comprises the set of typical

modelling intentions associated to the process of

modelling a business context. This set of related

modelling intentions comes along with a set of

achieving strategies. These strategies can be selected

for specific modelling situations according to the

predefined guideline arguments.

Actors&Units

Modelling

Business Object

Modelling

Stop

DAI13

DAI12

DAI21

DAI20

DAI15

DAI14

DSI11

DSI13

DSI14

Actor driven

strategy

Process In&Out based

strategy

Object driven

strategy

Actor´s responsibilities

based strategy

Role refining

strategy

Completness

strategy

Completness

strategy

Start

DAI23

DAI24

V&V

strategy

DAI25

AR V&V

strategy

DAI11

DAI18

Support process based

strategy

Business Process

Modelling

DAI22

Valued Chain strategy

Primary process based

strategy

DSI11

Events Modelling

DAI17

DAI16

DSI12

Event driven

strategy

Event driven

strategy

Object driven

strategy

DAI13

Restricted by BR based

strategy

DAI26

Technologies &

Business Rules

Modelling

DAI27

Business Rules

Refinement

strategy

DAI28

Technology

Details strategy

DSI15

DAI28

Technology based

strategy

3

2

4

7

1

6

5

Event driven

strategy

DAI29

8

9

10

11

12

13

Actors&Units

Modelling

Actors&Units

Modelling

Business Object

Modelling

Business Object

Modelling

Stop

Stop

DAI13

DAI12

DAI21

DAI20

DAI15

DAI14

DSI11

DSI13

DSI14

Actor driven

strategy

Process In&Out based

strategy

Object driven

strategy

Actor´s responsibilities

based strategy

Role refining

strategy

Completness

strategy

Completness

strategy

Start

Start

DAI23

DAI24

V&V

strategy

DAI25

AR V&V

strategy

DAI11

DAI18

Support process based

strategy

Business Process

Modelling

Business Process

Modelling

DAI22

Valued Chain strategy

Primary process based

strategy

DSI11

Events Modelling

Events Modelling

DAI17

DAI16

DSI12

Event driven

strategy

Event driven

strategy

Object driven

strategy

DAI13

Restricted by BR based

strategy

DAI26

Technologies &

Business Rules

Modelling

Technologies &

Business Rules

Modelling

DAI27

Business Rules

Refinement

strategy

DAI28

Technology

Details strategy

DSI15

DAI28

Technology based

strategy

3

2

4

7

1

6

5

Event driven

strategy

DAI29

8

9

10

11

12

13

• A roadmap is an easy way of expressing reusable

experience that can be updated when knowledge

about the process of modelling a business is

incremented or refined. Thanks to the guidelines

provided, a roadmap can be followed by anyone

even by non-specialised people.

• A roadmap is a way of collecting the

organisational knowledge involved in the process of

modelling a business domain or context. It can be

the starting point for building, exploiting and

controlling an important part of the organisational

memory. Besides, BMM helps in capturing two

types of the organisational knowledge. First, the

knowledge about business artefacts or elements such

as goals, technologies, business rules, business

processes, business objects, actors, job structure, and

events. Second, the knowledge about the way these

elements are captured, i.e. the process of modelling

the business itself.

• This knowledge may be selected, adapted and

reused as a whole or by process fragments (specific

sets of DAI´s) for modelling different business

contexts or domains.

Our future work will be concentrated in finding and

expressing more reusable experience for specialised

business domains. We work also, in the development

of a business modelling tool that will permit to

model a business by using BMM concepts and

roadmaps. By now, the tool is a working prototype

that allows modeller to define and represent

hierarchies of business goals and its corresponding

business processes.

It is important to mention that the BMM was used in

the development of a business model for the

Mérida’s Free Trade Zone office. This case study

provided a real environment that was complete and

complex enough for the purpose of evaluating and

improving the method. This experience is reported

in (Barrios et al., 2002) and (Barrios et al., 2003). A

first version of the BMM has been included as a

business modelling phase in METAS, a method for

planning the integrated automation of industrial

ICEIS 2004 - DATABASES AND INFORMATION SYSTEMS INTEGRATION

354

plants (Montilva et al., 2001). The method has been

extensively used as a teaching instrument for

developing small projects in several courses on

information systems and business modelling

conducted at the University of Los Andes in Mérida,

Venezuela. The knowledge expressed in the

roadmaps, comes from all these modelling

experiences and from others professional ones

acquired after 20 years working with IS contexts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported by the Venezuelan Fund for

Scientific and Technology Research (Fondo Nacional de

Ciencia y Tecnología - FONACIT) under grant number G-

97000824. The authors are also grateful to ZOLCCYT, a

free trade zone organisation at Mérida, Venezuela, for

providing a nice and stimulating environment that allows

the authors to fully apply, evaluate, and refine the BMM

method.

REFERENCES

Avison, D.E., Fitzgerald, G.: Where Now for

Development Methodologies. Communications of the

ACM, January, 46:1 (2003), 79-82.

Barrios, J. : Une méthode pour la définition de l’impact

organisationnel du changement..Thèse de Doctorat de

l’Université de Paris 1. (2001).

Barrios, J., Montilva, J., Suarez, G., Reyes, M.: Modelado

Empresarial de la ZOLCCYT. Informe Técnico,

UAPIT, Universidad de Los Andes, Venezuela, Junio

(2002).

Barrios, J., Montilva, J.: A Methodological Framework for

Business Modeling. 5

th

International Conference on

Enterprise Information Systems. Angers, France, April

(2003).

Booch, G., Rumbaugh, J. and Jacobson, I.: The Unified

Modeling Language User Guide. Addison-Wesley,

Reading Massachusetts (1999).

Brinkkemper, S.: Method engineering: Engineering of

information systems development methods and tools.

Information and Software Technology, 38 (1996) 275-

280.

Bruegge, B., Dutoit, A.H. Object-Oriented Software

Engineering. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ,

(2000).

Bubenko, J.: Enterprise Modelling, Ingénierie des

Systèmes d'Information, 2:6 (1994).

Eriksson, H. E., Penker, M.: Business Modeling with

UML: Business Patterns at Work. John Wiley & Sons,

New York (2000).

Flynn, D.J.: Information Systems Requirements:

Determination and Analysis, McGraw-Hill, London

(1992).

Fuenmayor, R.: Interpretando Organizaciones: Una Teoría

Sistémico-Interpretativa de Organizaciones. Consejo

de Publicaciones, Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida,

Venezuela. (2001).

Jarke, M., Rolland C., Sutcliffe A., Dömges R.. The

NATURE of Requirements Engineering, Shaker

Verlag, Aachen. (1999).

Krutchen, P.: The Rational Unified Process: An

Introduction. 2

nd

Edition. Addison Wesley, Reading,

Massachussetts (2000).

Martin, J., Odell, J.J.: Análisis y Diseño Orientado a

Objetos. Prentice Hall Hispanoamericana, México

(1994).

Marshall, C.: Enterprise Modeling with UML. Addison-

Wesley, Reading, MA (2000).

Montilva, J.: An Object-Oriented Approach to Business

Modeling in Information Systems Development. Proc.

of the III World Multiconference on Systemics,

Cybernetics and Informatics. Orlando, Florida, Vol. 2

(1999) 358-364.

Montilva, J., Hazam, K., Gharawi, M.: The Watch Model

for Developing Business Software in Small and

Midsize Organizations. Proc. of the IV World

Multiconference on Systemics, Cybernetics and

Informatics - SCI´2000. Orlando, Florida, July (2000).

Montilva, J., Chacón, E., Colina, E.: METAS: un Método

para la Automatización Integral en Sistemas de

Producción Continua. Revista Información

Tecnológica. Centro de Información Tecnológica,

Chile, 12(6), (2001) 147-156.

Montilva, J., Barrios, J.: A business Modelling Method

For Information Systems Development. XXIX

Conferencia Latinoamericana de Informática CLEI

2003. September 29, October 03. La Paz, Bolivia.

(2003).

Montilva, J., Barrios, J.: A Component-Based Method for

Developing Web Applications. 5

th

International

Conference on Enterprise Information Systems.

Angers, France, April (2003).

Odell, J.J.: A Primer to Method Engineering. INFOSYS:

The electronic newsletter for information systems,

3:19 (1996).

Porter, M.E.: Competitive Advantage. The Free Press.

New York (1985).

Piattini, M.G., Daryanani, S.N.: Elementos y Herramientas

en el Desarrollo de Sistemas de Información. Addison-

Wesley Iberoamericana, Delaware (1995).

Rolland. C, Grosz. G,. Nurcan. S. Enterprise Knowledge

development: the process view. Information and

Management. 36:3. September (1999).

Taylor, D.A.: Business Engineering with Object

Technology. John Wiley & Sons, New York (1995).

Van der Aalst, W.M.P, Barthelmess, P., Ellis, C.A.,

Wainer, J.: PROCLETS: A Framework for

Lightweight Interacting Workflow Processes. Int. J. of

Cooperative Information Systems (2000) 1—40.

Yourdon, E., Whitehead, K., Thomann, J., Oppel, K.,

Nevermann, P.: Mainstream Objects: An Analysis and

Design Approach for Business. Prentice Hall, Upper

Saddle River, NJ, (1995).

BUSINESS MODELLING THROUGH ROADMAPS

355