A Decision Game for Informal Learning

Bruno Souza

1

, Marcos Almeida

1

and Rui Pedro Lopes

2 a

1

Federal University of Technology – Parana, Campo Mour

˜

ao, Paran

´

a, Brazil

2

Research Center for Digitalization and Industrial Robotics, Instituto Polit

´

ecnico de Braganc¸a, Portugal

Keywords:

Informal Learning, Serious Games, Game-based Learning.

Abstract:

Lifelong learning implies that people are willing to change their attitude, way of thinking or acting, usually

based on some objective. For that, a decision game was developed for iOS and Android devices, using the

Unity Game Engine. The premise of the game puts the player in the role of a business manager facing situations

that require a decision. The game presents a card based mechanics, allowing the player to choose between

two options, sliding the card to the right or to the left, influencing the outcome of the game. The game allows

to use different decks of cards. The experience was assessed with the assistance of three instruments: closed

questions questionnaire, written exams before and after playing the game and observation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Informal learning can be defined as learning obtained

outside organized and structured classes (McCart-

ney et al., 2011). As a consequence of this defini-

tion, instead of traditional, in-classroom, pedagogical

methodologies, informal learning assumes anywhere,

anytime and self-learning approach, usually in infor-

mal settings or even in the workplace. Learning re-

sulting from daily and family-related activities, work

or leisure (such as games) can also be considered in-

formal learning (European Commission, 2001)

Regardless of the learning methodology, the ef-

fectiveness of the process strongly depends on the

motivation and involvement of the actors (usually,

the learner) (Mesquita et al., 2014; Lopes et al.,

2018). The scientific literature has been confirming

that motivation is higher when playing games (Pro-

topsaltis et al., 2011). This kind of educational games

(also known as serious games) includes objectives

and intentions beyond entertainment (Deterding et al.,

2011). Thus, serious games explicitly designed for

learning, if well planned and developed, can foster

the informal learning experience and succeed in the

construction of knowledge (Protopsaltis et al., 2011).

The methodology of using games for learning

(Game-Based Learning - GBL) allows players to ex-

perience different roles, take risks, make mistakes and

repeat without fear, encouraging the learner to contact

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9170-5078

and experience the content (Lopes, 2014; Pivec, 2007;

Ten

´

orio et al., 2018a,b).

In this paper, we describe the development and

use of a serious game with a focus on learning called

Escolha (Choice, translated from Portuguese). The

game adopts a decision making mechanics and it tar-

gets small, portable devices, such as smartphones.

2 SERIOUS GAMES FOR

MOBILE DEVICES

In general, students like to play and will usually play

constantly (Kalloo et al., 2010). Teachers have paid

attention to the use of games as a form of learning

and how these can contribute to improve and facili-

tate the learning processes (Yue and Ying, 2017). An

important aspect of the game design is the definition

of the game mechanics. This is a strategic element,

implemented with the purpose of providing a play-

ful experience (game mechanics) or learning activity

(learning mechanics) (Patino et al., 2016).

Nowadays, the use of mobile devices, such as

smartphones and tablets, is ubiquitous. In addition to

the broad connectivity possibilities, they can process,

present and transmit information and resources, such

as texts, sounds, images and videos (Fonseca, 2013).

The mobility and portability aspects also allow users

to take their mobile devices anywhere and use them at

any time (Hamid and Fung, 2007).

360

Souza, B., Almeida, M. and Lopes, R.

A Decision Game for Informal Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0010492403600367

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2021) - Volume 1, pages 360-367

ISBN: 978-989-758-502-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

The possibilities that these platforms introduce

have been making them an important terminal for

playing games. In this context, game research and

development on mobile devices has been done in sev-

eral areas. For example, in mathematics, Chang and

Yang (2016) present a game for learning basic geome-

try concepts, such as perimeter, area, surface, volume

and capacity. Based on the results through the appli-

cation of exams before and after the use of the game,

they demonstrated significant progress in the average

score of students.

In other area, namely citizenship, Chee et al.

(2010) used Statecraft X with 15-year-old students.

Yue and Ying (2017) described the development of

the History Learning Mobile Game (HLMG), which

aims to teach history in basic education.

Other contexts can also benefit from serious

games on mobile devices, such as teaching first aid to

individuals with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD),

where Urturi et al. (2011) have developed a game for

smartphones and tablets, with evidences that the game

contributed to enriching and increasing the impact of

education and therapy.

2.1 Related Games

Decision making allows the player to opt for different

actions according to a choice he has to make. There

are some games that build their gameplay and narra-

tive in this mechanics.

Papers, Please is an initially independent game

(Felan, 2014), developed by the American Lucas

Pope. Launched in 2013, it takes place in a dystopian

moment inspired by the cold war, in which a fictional

country, Arstotzka, reopens its borders in 1982, af-

ter six years at war with neighboring Kolechia. The

game’s protagonist is selected to work as an immi-

gration inspector at Grestin’s border checkpoint, Ar-

stotzka. As an immigration inspector, the protagonist

must control the flow of people entering Arstotzka

from Kolechia (Fassone, 2015).

For the inspector’s job at the immigration check-

point, the protagonist uses the documents provided by

the travelers and decides who can enter, who should

leave and later on in the game, who should be ar-

rested. The player’s role in Papers, Please is to con-

trol the protagonist, who at no time is shown or has

his identity revealed.

The player must always check for discrepancies

in travelers’ documents and whether they meet the

requirements for entry to Arstotzka. In addition to

checking travelers’ documents, later in the game, the

resources to search and analyze fingerprints are made

available. Throughout the game, smugglers, spies and

terrorists are hiding among the immigrants, so, in ad-

dition to the approving and refusing, the player has

the option of arresting an immigrant. In addition to

the management of immigrants, the protagonist has a

family to support: wife, son, mother-in-law and un-

cle. Each day of the game, the player must meet as

many people as possible to receive a higher salary,

but if he makes a wrong decision, he suffers a penalty.

Papers, Please is a management and decision-making

game with simple mechanics, in which it brings the

player the responsibility of managing the entry of im-

migrants and supporting their family, allowing the

construction of a character throughout history even

without having their identity revealed (Paul Formosa,

2016).

Reigns is a game developed by Nerial and pub-

lished by Devolver Digital

1

. Released in 2016, it has

support for Android, iOS, Linux, MacOS and Mi-

crosoft Windows platforms. The game takes place in

a fictional medieval world, where the player assumes

the role of a monarch and rules a kingdom making de-

cisions. The goal is to govern for as long as possible

without unbalancing the pillars of society: the clergy,

the people, the army and finance. In case he cannot

keep the balance, the king is killed and a new king

starts to rule, so the player to each new king tries to

conquer new goals (Hern, 2016).

The main form of gameplay used in Reigns is de-

cision making by sliding cards right and left. The

cards are displayed randomly to the player, present-

ing a situation where he must make a decision. Each

card is composed of one character, text and two op-

tions to choose from. With each choice made by the

player, changes occur in resources as consequences,

increasing or decreasing the pillars of his kingdom.

Lapse: A Forgotten Future is an independent

game, developed by Stefano Cornago

2

. Following the

same graphic style and gameplay as Reigns, in Lapse

the player assumes the role of a president, who wakes

up without knowing what happened in the past and

how he became president, so he must make decisions

before several characters to control his country in a

world post-apocalyptic and with nuclear wars in the

year 2075. The game uses the interaction of swiping

right and left when making decisions and with charac-

ters in the form of cards. With each decision making,

a change occurs in the pillars of environment, pop-

ulation, army and finance. The player must always

ensure that none of the pillars zero or fill completely,

as it will cause the president to die. Unlike Reigns,

when the protagonist dies, he is not replaced by a new

1

https://www.devolverdigital.com/games/view/reigns

2

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.

cornago.stefano.lapse

A Decision Game for Informal Learning

361

president, but ends up waking up again. Another dif-

ference is that with each decision made, a day passes

and not a new year. Even with a shorter story, the

game has three different endings in addition to death.

In Nirvana: Game of Life

3

, the player assumes the

role of a soul that is born as a person, and, when dy-

ing, he is born as a new person, maintaining this cycle

until the end of the game. During life, you must make

everyday decisions, but managing so that there is no

imbalance in the pillars of health, happiness, popular-

ity and money. Among the games presented, Nirvana

has the simplest graphic style. Also using the swipe

to the right and left as a form of interaction, the cards

show only text, without the silhouette of a character

as in Reigns and Lapse.

Every new person starts at the age of one, and with

each decision, a year passes. In the game you can

see the cemetery, which shows the people whom the

player controlled, and how long they lived. In addi-

tion to death, the game has three different endings.

Nirvana: Game of Life is a simple game, focused on

history, with a lot of humor and everyday life deci-

sions. Its gameplay is intuitive and easy to learn, the

player uses the slide of the cards to the right or to the

left, always trying to manage so as not to unbalance

the four pillars of the game.

Soccer Kings is a game developed by Tapps

Games

4

. The game takes place in a football scenario,

in which the player controls a coach hired by a team

and must make management decisions to lead the club

to success. With each decision a month passes in the

game. Its main objective is to keep the three pillars

balanced: management, fans and players. In the event

of an imbalance, the coach is fired and the game is

restarted with a new coach. Similar to the games al-

ready presented, in Soccer Kings the characters are

presented in the form of cards, and you must answer

them with a swipe to the right or left, which makes

the learning curve very accessible.

2.2 Sliding Cards for Decision Making

According to the references in the literature and the

success and diversity of games, it is possible to say

that the mechanics of sliding cards for decision taking

is popular, with several examples of interesting and

motivating games. The process of decision making

also has the potential to increase the reflection time

and, consequently, the effort players use in the pro-

cess, which can have positive results in the learning

process (Glass et al., 2013).

3

http://goldtusks.com

4

http://tappsgames.com/

In this work, we decided to develop a decision

game, based on sliding cards mechanics, to support

informal learning, targeting mobile devices so that it

can be played anytime, anywhere.

3 GAME PROPOSAL

The Escolha game puts the player in the role of a busi-

ness manager, in which he must make decisions and

define an underlying strategy so that the finances and

reputation of his company do not suffer. The situa-

tions brought by the cards and the associated choices

depend on the content area, so if the purpose is to

learn about cybersecurity, for example, the situations

presented for decision making will follow the same

topic.

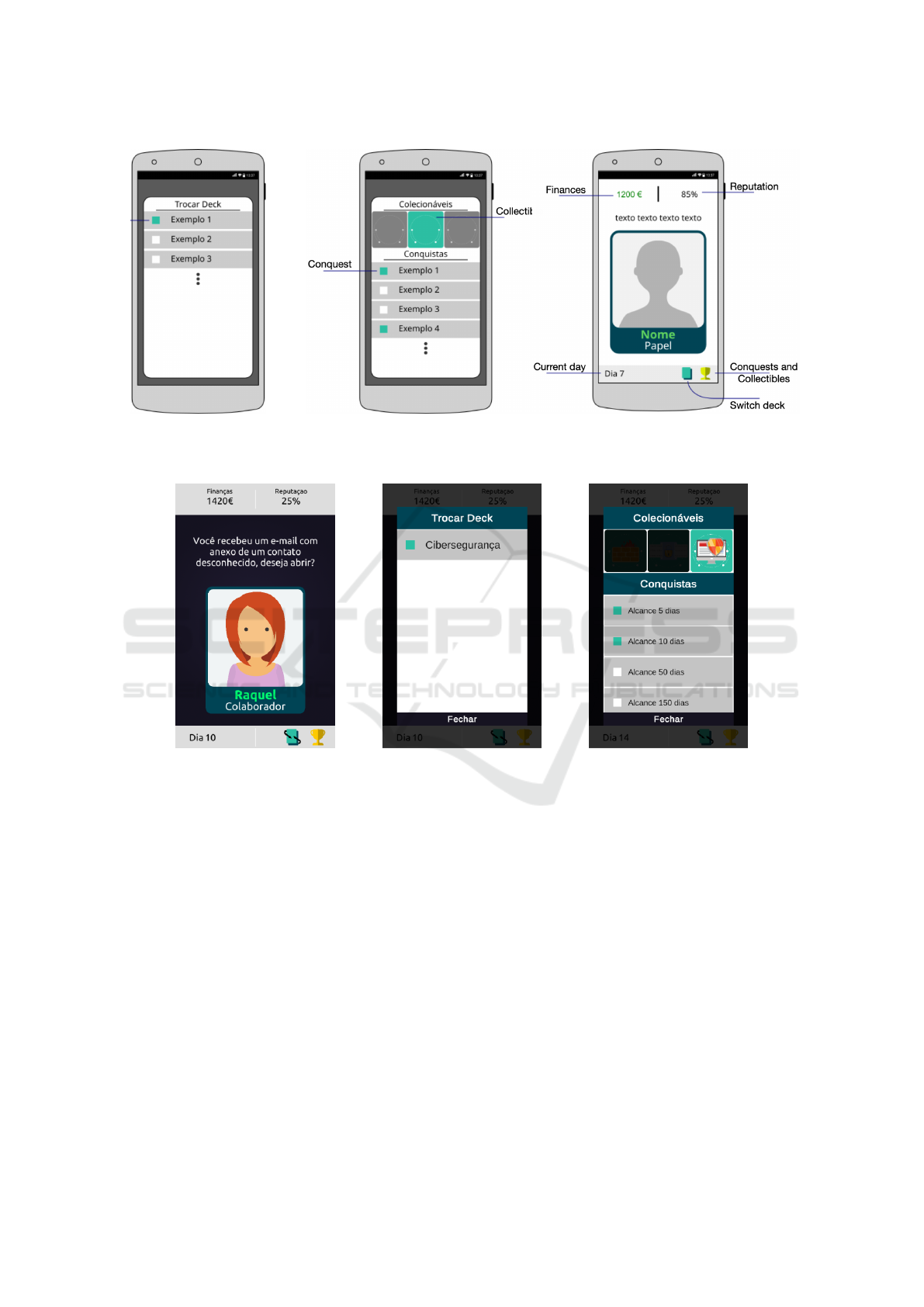

3.1 User Interface

The game starts on the first day (day 0) and with each

decision the calendar advances to a new day. If the

game finishes, because the company has run out of

money or has been unable to keep a good reputation,

the game is restarted, returning to day 0. The user

interface and user experience are based on a deck of

cards in which each card presents a situation to the

player for a decision to be made. The deck encloses

the content to be learned by the player and it is possi-

ble to create several decks, that the player can choose

from (Figure 1a). The deck, besides the content, also

defines the narrative, such as the area of operation of

the company, and other elements, including charac-

ters, conquests and collectibles (Figures 1a and 1b).

The main screen of the game provides two but-

tons, one for changing decks and another to access

the list of conquests. It is also possible to observe the

percentage referring to the reputation, the current day,

the amount of money and, in the center, the current

card with a description above (Figure 1c).

The conquests and collectible cards are extra goals

to be conquered by the player during the game, kept

even if he loses. Collectible cards do not present a

choice situation but, instead, items that should be re-

trieved and collected by the players.

The achievements are objectives to be obtained

during the game. They can represent time (the num-

ber of consecutive days playing Escolha), effort (the

number of matches) or others (for example, if the

player reaches 30 days without losing or obtaining 3

specific collectible cards). Some conquests result di-

rectly from the choices, for example, an achievement

in which he must invest in the reuse of paint. The final

aspect of the game is depicted in Figure 2.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

362

(a) Switch deck. (b) Conquests and Collectibles. (c) Home screen.

Figure 1: Some Escolha screens.

Figure 2: Final design.

3.2 Deck Design

The game supports several decks, with a random

number of cards. The decks are designed consider-

ing the content area and the challenges the player will

face. So, deck design should be simple and the game

should be able to download decks at runtime.

Each card contains a numeric identifier, a descrip-

tion, the character name, the options available and

their respective consequences. This information will

be used in the user interface, with the characters’ sil-

houette, names and roles. They can be collaborators,

customers, suppliers or community members. Each

character can be referenced in several cards, so it

can appear multiple times, but in different decision-

making situations.

Achievements and collectible cards are objectives

to be achieved by the player during the game. Even

if the finances or reputation are zeroed, reaching the

end of the game, the goals already achieved are saved

in the player’s scoreboard.

All decks are defined in structured files, in

JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) format, contain-

ing all information, such as character, cards, options,

consequences, achievements and collectibles. This al-

lows the game to be easily changed, and new content

can be added simply by modifying the structured files,

or by creating a new file for a new deck.

3.3 Game Instrumentation

In addition to the game, additional software was

added to implement instrumentation that collects

game data and exports them to the cloud. The pur-

pose is to receive anonymous information about the

players’ choices, for analysis and feedback.

A Decision Game for Informal Learning

363

The endpoint was developed in Python and Flask,

waiting for data in JSON format from the game.

Among the information submitted to the cloud, there

is a unique identifier per device, the sequence of cards

and the player’s decisions, along with the date and

time of the decision, the achievements and the col-

lectibles obtained. Such information is separate for

each deck. The submission occurs after each player’s

choice.

The game was implemented in Unity, targeting

the Android and iOS platforms. The engine has the

necessary libraries already in place, requiring specific

compilation afterwards. In this context, the game was

compiled to Android using Android Studio (in Win-

dows) and for iOS using Xcode in macOS. The result-

ing packages were installed in test devices, that were

used by the students in class.

4 TEST AND EVALUATION

Escolha is intended to be played at random times and

places, without time constraints or limits. This means

that the player should be able to retrieve his phone,

play for a couple of minutes, and, later, resume other

activities. If he wants to play more time, it is also

possible.

The game dynamics occurs as follows. A thematic

deck of cards is chosen by the player, marking the

context of the choices and narrative. Each card will

be presented randomly to the player and, after mak-

ing a decision, the consequences of the choice must

be applied, and the card will be marked as displayed.

Cards that have already been shown are only repeated

if there are no more new cards to be presented. The

game can be interrupted and resumed at later time.

For testing purposes, a test and evaluation scenario

was built, according to a specified methodology.

4.1 Methodology

First, a deck of cards under the area of cybersecurity

was built, based on the course Introduction to Cy-

bersecurity, version 2.1 from the Cisco Networking

Academy

5

. This course has 5 chapters with notions

about attacks, protection and privacy of personal data

and the protection of an organization. The deck con-

sisted of 30 decision cards, with 5 characters, 3 col-

lectible cards and 11 achievements, in a total of 44

cards. All the content focuses on cybersecurity deci-

sion making, presenting to the player, as a manager,

5

https://www.netacad.com/courses/cybersecurity/

introduction-cybersecurity

situations about personal and company data, team and

employee management, and internal networks and

systems.

A total of 61 students from different study pro-

grams, including a class from the Degree in Computer

Engineering, Degree in Electrical and Computer En-

gineering, Superior Professional Technician in Cyber-

security and Superior Professional Technician in Soft-

ware Development, participated in the test. Of these,

41 played the game.

The students were volunteers and they played the

game in classroom. There was an initial questionnaire

with questions to assess the game playing habits and

opinion and perceptions on the topic of cybersecurity.

Then, the classes were divided into two groups, and

only one group played. After the first questionnaire,

students were given time to obtain the game and in-

stall it on their mobile devices. Three days were used

for the evaluations and, on average, each class used 40

minutes to answer the initial questionnaire and play

the game.

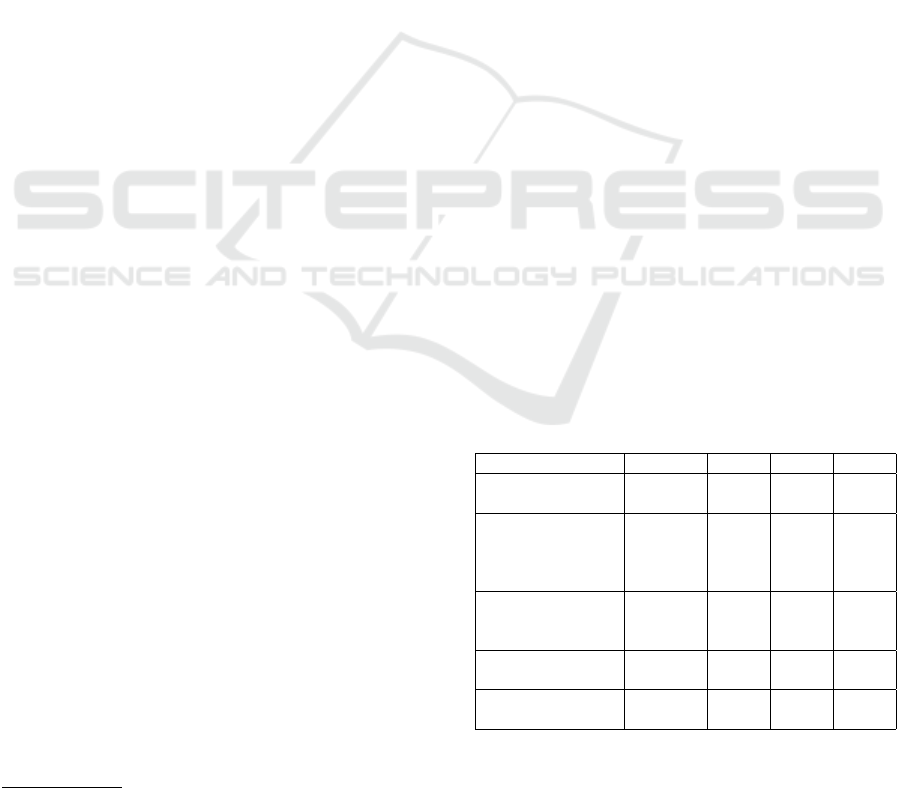

4.2 Results

During the evaluation period, players’ decisions data

were retrieved and submitted anonymously to the

cloud, in which it is possible to analyze some aspects

about the gameplay and dynamics of the game.

From the JSON file with the users’ decisions,

some information was extracted and summarized,

such as playing time, time for decision making, num-

ber of decisions, decision changes for the same card

and the management of finances and reputations (Ta-

ble 1). The average playing time was 14 minutes,

enough to explore the whole game, the mechanics and

achievements.

Table 1: Player statistics during evaluations.

Average SD Max Min

Game time

(min:s)

14:10 08:32 32:18 00:25

Time for each

decision in

the 1st minute

(min:s)

00:14 00:10 00:56 00:02

Time for each

decision in 15 m

(min:s)

00:11 00:14 06:53 00:01

Decisions per

player in 8 min

32.4 17.2 80.0 4.0

Decisions per

player in 15 min

56.7 35.6 138.0 4.0

On average, in the first 8 minutes, 32 decision

cards were presented to the player. The remaining

achievement and collectible cards were presented and

collected also in this time. After 15 minutes, the play-

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

364

ers, on average, have already made 56 choices, al-

most the double of the possibilities contained in the

cybersecurity deck. Soon, after this time, the game

becomes repetitive, as there are no new situations to

be presented to the players. This revealed that 30 de-

cision cards provides a very short experience.

The adaptation to the game mechanics was also

analyzed, through the average time taken for each

choice. In the test, no demonstrations or tutorials

were made to the students, so they had to explore the

game autonomously. In the first minute, it is observed

that the average for each decision is 14 seconds. It

was observed that when some students had discovered

the mechanics of sliding the cards, they passed on tips

to their colleagues. The fact that decisions take on av-

erage more than 10 seconds can demonstrate that stu-

dents read, interpret situations and options, and then

make choices based on the finances and reputation,

something important for the purpose of learning.

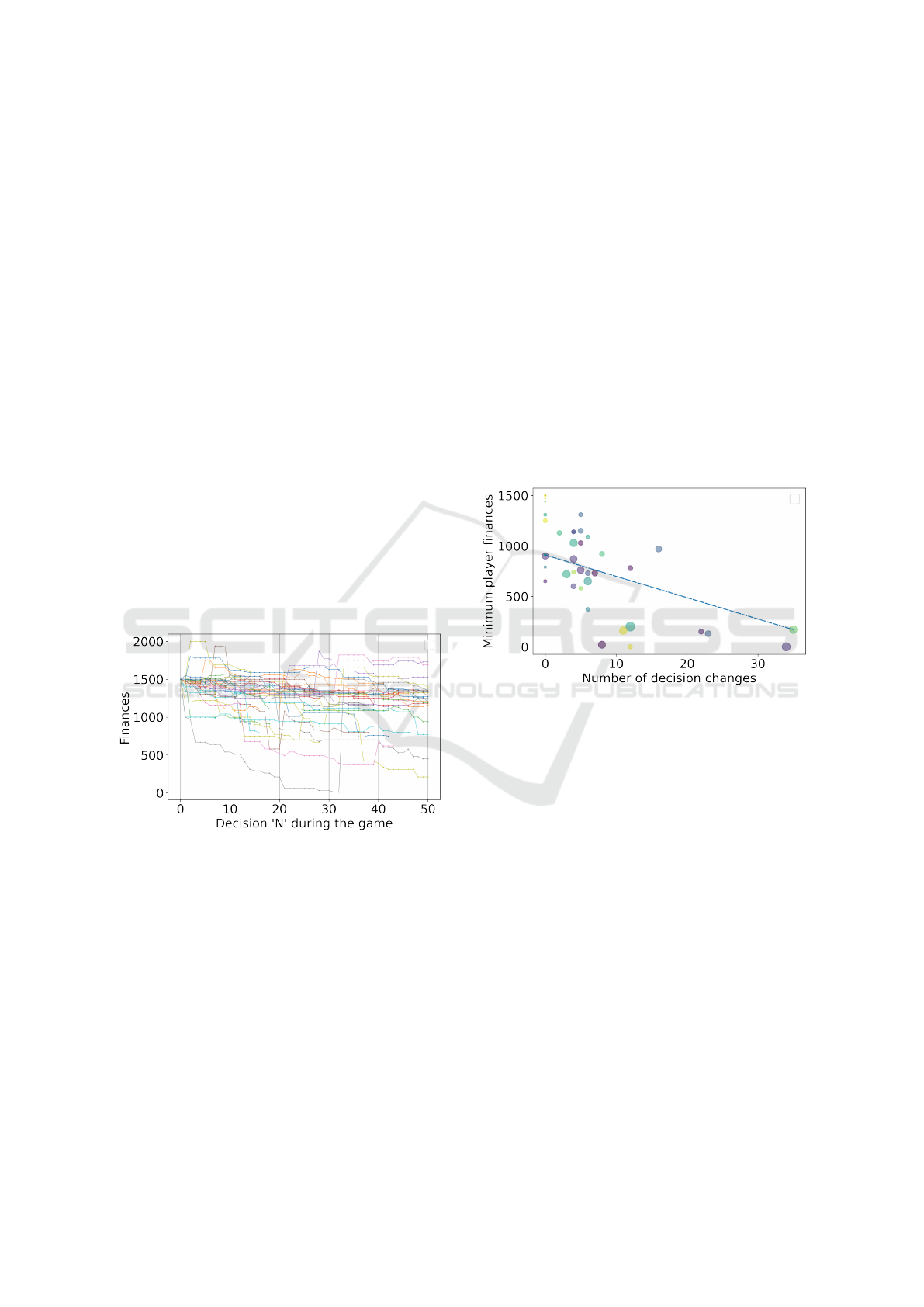

Initially on the cybersecurity deck, every player

starts with 1500 euros of finance. In order to consider

the consequences of balanced decisions, one can ob-

serve the variation of the players’ finances throughout

the game. In case the player gradually increases his

finances, it indicates that the consequences are mild

and the game is easy (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Evolution of the players’ finances.

It is observed that the players do not tend to devi-

ate much from the initial finances. It is concluded that

the game can be balanced, but not challenging. This

is something that should be improved in the design of

the decks.

With data for each player, it was verified whether

there is a relationship between variables using a cor-

relation coefficient that can indicate patterns in the

players’ behavior. The coefficient helps us to under-

stand relationships between two variables in the data

set. In this work, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was

used. The Pearson coefficient indicates whether two

variables are linearly proportional or inversely pro-

portional. The coefficient is always given in the range

of -1 to 1, with 1 indicating that variables are propor-

tional and -1 inversely proportional. Next to number

1, it indicates that, when a variable tends to grow, the

one that is being verified the relationship also tends

to grow. The opposite for coefficients close to -1, in

which when a variable tends to increase, the one be-

ing verified the relationship tends to decrease. If the

coefficient is close to 0, the variables have no correla-

tion.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated

using the Pandas library with Python. The correla-

tion coefficient between the variables in the data set

was calculated, and in this analysis it was possible to

obtain two possible relationships. The first is the re-

lationship between the amount of changes in a card

presented again and the minimum finances the player

had during the game. The diameter of each point in-

dicating the number of total player choices (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Correlation between choices change and mini-

mum game finance.

A decision change is assumed when a card is pre-

sented to the player, he then makes a choice and, when

this card is presented again to the player, he makes a

different decision. In the first relation, the coefficient

obtained was -0.69, that is, players who tend to make

different decisions are those who, over the course of

the game, occasionally had fewer finances. This rela-

tionship can indicate that players who made bad de-

cisions, reducing their finances, when they had new

opportunities, changed their choices.

One final analysis was made to assess the percent-

age of good and bad choices for each player (Figure

5). Analyzing the relationship between the number of

bad decisions and the percentage of change from pre-

vious decisions, we note a correlation of 0.81. The

diameter of each point indicating the total number of

choices each player did.

Players who make bad choices tend to change

their decisions more for the cards presented again.

Therefore, from the two relations obtained, it can be

concluded that the players who change their choices

A Decision Game for Informal Learning

365

Figure 5: Correlation between good and bad choices.

are also the ones who make bad decisions and occa-

sionally have smaller finances.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This work describes the design and development of a

game for informal learning. The game was inspired

by a sliding cards mechanics, compatible with the re-

duced screen size of mobile devices. This allows the

player to make binary decisions when faced with sit-

uations in the role of a business manager. The situ-

ations presented to the player are contextualized ac-

cording to the subject of learning.

The game was tested and evaluated by 41 students,

in order to obtain results about the game. They re-

veal that the playfulness and difficulty strongly de-

pend on the deck design. These should include diffi-

cult choices and, eventually, a chance probability for

changing the outcome of the narrative. Moreover, the

deck should have more cards, to extend the duration

of the game.

Nevertheless, this game allows the dealing with

different content and areas. In future work, it makes

sense to create an online library for sharing decks,

which improves the game’s relevance. Another aspect

to consider is add a possibility for multiple choices,

maintaining the game mechanic as simple as possible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been supported by FCT – Fundac¸

˜

ao

para a Ci

ˆ

encia e Tecnologia within the Project Scope:

UIDB/05757/2020.

REFERENCES

Chang, R.-C. and Yang, C.-Y. (2016). Developing a mobile

app for game-based learning in middle school mathe-

matics course. In International Conference on Applied

System Innovation (ICASI, pages 1–2.

Chee, Y., Tan, E., and Liu, Q. (2010). Statecraft X: Enact-

ing Citizenship Education Using a Mobile Learning

Game Played on Apple iPhones. In 6th IEEE Inter-

national Conference on Wireless, Mobile, and Ubiq-

uitous Technologies in Education, pages 222–224.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., and Nacke, L. E.

(2011). From Game Design Elements to Gameful-

ness: Defining Gamification. In MindTrek’11, Tam-

pere, Finland. ACM.

European Commission (2001). Making a European area

of lifelong learning a reality. In Communication from

the Commission. COM(2001) 678 final. In European

Commission. Brussels, Belgium.

Fassone, R. (2015). Isto

´

e um jogo de v

´

ıdeo: jogos de v

´

ıdeo,

autoridade e metacomunicac¸

˜

ao. Comunicac¸

˜

ao e So-

ciedade, 27:19–35.

Felan, P. (2014). Indie Game Studies Year Eleven. In Di-

GRA’13 - Proceedings of the 2013 DiGRA Interna-

tional Conference: DeFragging Game Studies.

Fonseca, A. (2013). Aprendizagem, mobilidade e con-

verg

ˆ

encia: mobile learning com celulares e smart-

phones. Revista Eletr

ˆ

onica Do Programa de P

´

os-

Graduac¸

˜

ao Em M

´

ıdia e Cotidiano, 2(2):265.

Glass, B. D., Maddox, W. T., and Love, B. C. (2013). Real-

Time Strategy Game Training: Emergence of a Cog-

nitive Flexibility Trait. PLoS ONE, 8(8):e70350.

Hamid, S. and Fung, L. (2007). Learn Programming by

Using Mobile Edutainment Game Approach. In 2007

First IEEE International Workshop on Digital Game

and Intelligent Toy Enhanced Learning, volume DIG-

ITEL’07, pages 170–172.

Hern, A. (2016). Reigns review: the medieval strategy game

based on Tinder. The Guardian.

Kalloo, V., Kinshuk, and Mohan, P. (2010). Personal-

ized game based mobile learning to assist high school

students with mathematics. In Proceedings - 10th

IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learn-

ing Technologies, ICALT, pages 485–487.

Lopes, R. (2014). An Award System for Gamification in

Higher Education. In ICERI2014 Proceedings, pages

5563–5573.

Lopes, R. P., Mesquita, C., de la Cruz del R

´

ıo-Rama, M.,

and

´

Alvarez Garc

´

ıa, J. (2018). Developing Sustain-

ability Awareness in Higher Education. In Peris-Ortiz,

M., G

´

omez, J. A., and Marquez, P., editors, Strategies

and Best Practices in Social Innovation: An Institu-

tional Perspective, pages 131–152. Springer Interna-

tional Publishing, Cham.

McCartney, R., Eckerdal, A., Mostr

¨

om, J., Sanders, K.,

Thomas, L., and Zander, C. (2011). Computing stu-

dents learning computing informally. In Proceedings

of the 10th Koli Calling International Conference on

Computing Education Research, pages 43–48.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

366

Mesquita, C., Lopes, R. P., Garc

´

ıa, J. l., and Rama, M. d.

l. C. d. R. (2014). Pedagogical Innovation in Higher

Education: Teachers’ Perceptions. In Peris-Ortiz, M.,

Garrig

´

os-Sim

´

on, F. J., and Gil Pechu

´

an, I., editors,

Innovation and Teaching Technologies: New Direc-

tions in Research, Practice and Policy, pages 51–60.

Springer International Publishing, Cham.

Patino, A., Romero, M., and Proulx, J. (2016). Analy-

sis of game and learning mechanics according to the

learning theories. In 8th International Conference on

Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications,

VS-Games, pages 1–4.

Paul Formosa, Malcolm Ryan, D. S. (2016). Papers, Please

and the systemic approach to engaging ethical exper-

tise in videogames. Ethics and Information Technol-

ogy, 18(3):211–225.

Pivec, M. (2007). Play and learn: potentials of game-based

learning. British Journal of Educational Technology,

38(3):387–393.

Protopsaltis, A., Pannese, L., Pappa, D., and Hetzner, S.

(2011). Serious Games and Formal and Informal

Learning. ELearning Papers, 25(July 2011):1–10.

Ten

´

orio, M., Reinaldo, F., Esperandim, R., Lopes, R.,

Gois, L., and Dos Santos Junior, G. (2018a). C

´

eos:

A collaborative web-based application for improving

teaching-learning strategies. In Advances in Intelli-

gent Systems and Computing, volume 725, pages 107–

114.

Ten

´

orio, M. M., Reinaldo, F. A. F., G

´

ois, L. A., Lopes,

R. P., and dos Santos Junior, G. (2018b). Elements

of Gamification in Virtual Learning Environments. In

Auer, M. E., Guralnick, D., and Simonics, I., editors,

Teaching and Learning in a Digital World, Advances

in Intelligent Systems and Computing, pages 86–96.

Springer International Publishing.

Urturi, Z., Zorrilla, A., and Zapirain, B. (2011). Serious

Game based on first aid education for individuals with

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) using android mo-

bile devices. In 16th International Conference on

Computer Games (CGAMES, pages 223–227.

Yue, W. and Ying, C. (2017). The Evaluation Study of Gam-

ification Approach in Malaysian History Learning via

Mobile Game Application. In 2017 IEEE 17th Inter-

national Conference on Advanced Learning Technolo-

gies (ICALT, pages 150–152.

A Decision Game for Informal Learning

367