Design and Practice of ESD in High School in Japan

through Online Video Co-creation Workshop

Shun Arima, Fathima Assilmia, Marcos Sadao Maekawa and Keiko Okawa

Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University, Yokohama, Japan

Keywords:

ESD, Workshop, Video Creation, Co-creation, SDGs, Online Learning.

Abstract:

This paper discusses the design and practice of ESD (Education for Sustainable Development) through an

online video co-creation workshop for Japanese high school students. Our research group has designed a

workshop program that co-creates short videos to promote the UN SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals).

The workshop took place from July to December 2020 and involved 112 Japanese high school students. The

workshop consists of four phases: Research, Planning, Making, and Reviewing. Through questionnaires and

qualitative observational surveys, we analyzed whether participating students could learn the seven abilities

and attitudes emphasized in ESD in each phase. As many learning environments shift to online due to COVID-

19, this paper explores ESD workshops that can be realized even in online environments, contributing to ESD

research.

1 INTRODUCTION

This paper discusses the design and practice of ESD

(Education for Sustainable Development) in Japan’s

high schools through an online video co-creation

workshop. The workshop was held online from July

to December 2020 for 112 Japanese high school stu-

dents. In this workshop, the students co-created short

videos to promote the UN SDGs. The workshop con-

sisted of four phases: Research, Planning, Making,

and Reviewing. Through these four phases of video

co-creation, students could learn various abilities and

attitudes, including critical thinking and collaboration

with peers. Through the design and practice of this

online workshop, this paper explores the potential of

online video co-creation as an ESD method that can

be implemented in the COVID-19 era by examining

the qualitative data provided by the participating stu-

dents.

The United Nations Decade of Education for Sus-

tainable Development (DESD) was rolled out world-

wide from 2004 to 2014. It encouraged efforts to

change the education system for sustainable devel-

opment (UNESCO, 2014). The Global Action Pro-

gramme (GAP) on ESD was launched in 2015 as

a successor to DESD. In 2019, ESD for 2030 was

adopted by UNESCO and acknowledged by the UN;

it is the new framework for these activities (UN-

ESCO, 2020).

The trend in ESD-related activities among inter-

national organizations indicates the importance of

further ESD designs and practices. Various peda-

gogical approaches to ESD have been implemented

(Stubbs and Schapper, 2011; Pappas et al., 2013;

Lozano et al., 2017). For example, there are role-

plays and simulations (Cotton and Winter, 2010),

oral presentations and project learning (Ceulemans

and De Prins, 2010), and behavior-oriented methods,

such as internship learning, solving actual community

problems, and outdoor education (Lambrechts et al.,

2013). However, even though so many approaches

exist, many methods have not yet been validated as

ESD methods (Lozano et al., 2017). Further designs

and practices relating to educational methods for ESD

are needed.

In particular, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to

a shift to an online environment for many learning

opportunities, and it is necessary to respond to this

change (Reimers and Schleicher, 2020). However,

there is not enough research on implementing ESD

practices during a pandemic. The present study will

contribute to the research on ESD that can be ap-

plied in the future based on the knowledge gained

through the design and practice of actual workshops

amid COVID-19.

Japan is the country that proposed DESD to the

United Nations. The Ministry of Education, Culture,

Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) has pro-

640

Arima, S., Assilmia, F., Maekawa, M. and Okawa, K.

Design and Practice of ESD in High School in Japan through Online Video Co-creation Workshop.

DOI: 10.5220/0010486806400647

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2021) - Volume 1, pages 640-647

ISBN: 978-989-758-502-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

moted ESD practices in schools. MEXT’s final re-

port on ESD research in Japan stipulated seven abil-

ities and attitudes to be emphasized in ESD (Table

1) (MEXT, 2016).

Table 1: Seven abilities and attitudes to be emphasized in

ESD (MEXT, 2016).

1. Ability to think critically

2. Ability to plan with anticipation of a future scenario

3. Multidimensional and integrative thinking

4. Communication skills

5. Ability to cooperate with others

6. Respectful of relations and connections

7. Proactive participation

The report presents examples of group creative ac-

tivities as a concrete educational approach to devel-

oping these abilities and attitudes. With these exam-

ples in mind, our team has adopted video co-creation

to equip students with these abilities and attitudes.

Video co-creation reportedly has many educational

effects (Hawley and Allen, 2018). and Video creation

is active learning (Greene and Crespi, 2012), develops

communication skills (Or

´

us et al., 2016; Alpay and

Gulati, 2010), and has the advantages of collaboration

and teamwork (Ryan, 2013; Alpay and Gulati, 2010).

It is also a learning method that enhances motivation

and engagement (Pereira et al., 2014; Alpay and Gu-

lati, 2010; Cox et al., 2010). The educational benefits

expected of these video co-creations are in many ways

common to the seven abilities and attitudes mentioned

above and have many benefits. Therefore, our team

thought that the video co-creation workshop could be

adapted as an ESD practice.

This research aims to explore the possibilities

of online video co-creation workshops as an ESD

practice. To that end, through workshops designed

and practiced by our research group, we examined

whether the participating students were able to ac-

quire the seven abilities and attitudes shown in (Table

1). This validation was conducted using qualitative

data from student questionnaires and observations in

each of the workshop’s four phases: Research, Plan-

ning, Making, and Reviewing.

After discussing the background and the purpose

of this research in 1. Introduction, this paper reviews

the related studies of this study in 2. Literature Re-

view. In 3. Design, we describe details of the work-

shop’s design, and in 4. Practice, we describe the de-

tails of practice for each of the four phases. After that,

5. Findings & Discussions reveals whether the stu-

dents acquired the seven abilities and attitudes from

qualitative data from questionnaires and observations

and suggestions for improvement. In 6. Conclusion,

we conclude this research and describe its limitations.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 ESD and Online Learning

Trevors and Saier (2010) claimed that education is

the most important tool for reshaping worldviews

and values and has significant potential to tackle

the sustainability challenges facing humanity. The

strength of university learners’ sustainability abilities

is positively correlated with sustainability contribu-

tions (Lozano et al., 2019). Lohrmann (2017) states

that massive open online courses (MOOCs) offer spe-

cific benefits to people’s educations and careers in

non-OECD countries (especially people with rela-

tively little access to education) and make a substan-

tial contribution to the normative concept of ESD.

The University of Worcester in the United King-

dom has created a website where information on sus-

tainability learning can be shared within the univer-

sity, which has been confirmed as effective in the crit-

ical thinking and engagement of students (Emblen-

Perry et al., 2017). Furthermore, students who partic-

ipate in sustainability programs in higher education

e-learning offered by Portuguese universities have

achieved a high level of motivation and satisfaction

and achieved effective learning outcomes (Azeiteiro

et al., 2015).

2.2 Video Creation and Education

Shewbridge and Berge (2004) claim that making

videos has become very familiar to us thanks to the

advent of low-cost consumer cameras and computer-

based editing software. Furthermore, YouTube and

social networking services (SNS) have evolved video

beyond TV broadcasting and movies. Video has be-

come one of the crucial methods of self-expression

and communication in modern youth culture (Chau,

2010; Madden et al., 2013). Greene and Crespi (2012)

stated that 21st-century students, whom they called

“digital natives,” often have existing technical skills

and experience in video creation. Educational re-

search also emphasizes the importance of encourag-

ing the use of digital technologies and of the develop-

ment of these skills in higher education (Pereira et al.,

2014).

A lot of effort is put into creating videos in educa-

tional settings as part of collaborative learning (Ca-

yari, 2014; Gilje, 2010; Redvall, 2009). Jaramillo

(1996) explained that creative group activities lead to

social interaction with other people, and social inter-

action creates opportunities to earn a higher level of

knowledge. So, collaborative learning is an effective

method from an educational standpoint.

Design and Practice of ESD in High School in Japan through Online Video Co-creation Workshop

641

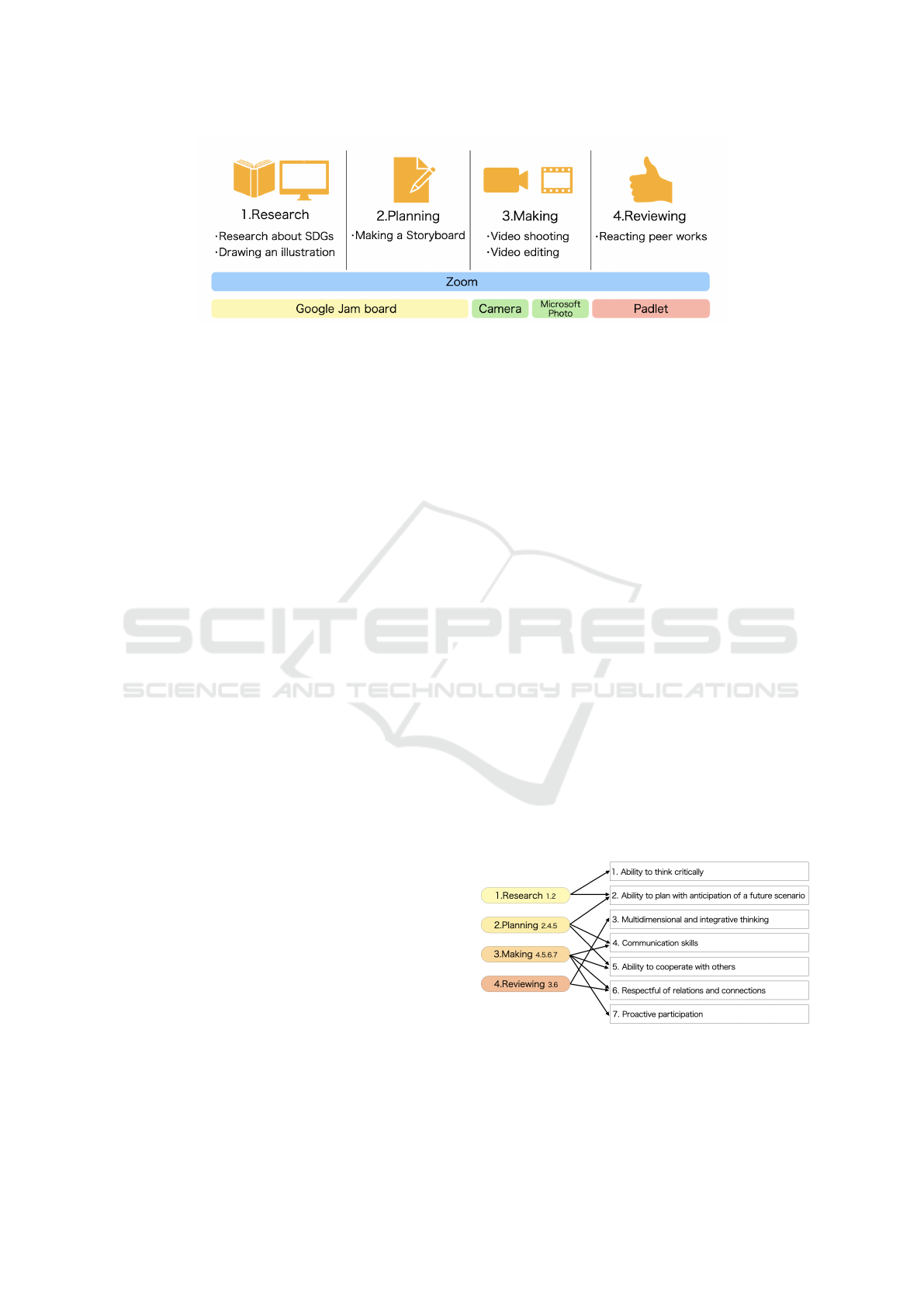

Figure 1: Workshop flow in four phases and the tools used for each phase.

2.3 Media Creation for Global Learning

Several studies have investigated global learning

through media creation. Media resources such as pho-

tography, mass media, and digital learning experi-

ences offer students a better understanding of multi-

ethnic societies. Students can also use digital media

in the classroom to broaden their horizons (Hobbs and

Moore, 2013).

Sharing information in today’s world is becoming

increasingly dependent on digital media. Therefore,

communication skills and using digital media effec-

tively are becoming increasingly important to today’s

generation; the combination of these two skills is very

beneficial and relevant (Schrum et al., 2017).

Topoklang et al. (2018) ’s study targeted elemen-

tary school students and attempted to reflect their cul-

ture and communication styles with people of the

same generation from overseas through making stop-

motion animation.

3 DESIGN

3.1 Context

Our research group conducted this workshop in col-

laboration with a private high school in Tokyo, Japan.

The target group consisted of 112 first-year students.

The facilitation team consisted of six to ten univer-

sity faculty members and graduate students, some of

whom had previous experience in creating videos.

The workshops were held one a month over six ses-

sions from July to December 2020, except for August,

which had an additional session. Each workshop con-

sisted of a 120-minute class, and the teams that did

not finish their work within that time did the rest as

homework outside of the class.

Due to COVID-19’s influence, all workshop ac-

tivities were conducted online, and only some video

creation work, such as shooting, was done offline (in

high school). All students own a Microsoft Surface,

and most of the workshop activities were done using

the Surface. We also used Zoom for all online work-

shop communications. Zoom has a breakout room

function that divides participants into multiple small

groups, suitable for group work such as this work-

shop.

Our research group used SDGs as the subject of

video creation in this workshop. SDGs and ESD are

closely related. ESD for 2030 focuses on education’s

contribution to SDG achievements. SDGs #4 recog-

nize quality education as a means of achieving the re-

maining SDGs; ESD, in particular, is an integral part

of Target 4.7. Besides, SDGs have many data and

materials published on the Internet and are a common

topic worldwide. Therefore, we decided that using

SDGs as a theme for video creation would be an ef-

fective ESD practice.

3.2 Goal and Flow

This workshop ultimately aims for participating stu-

dents to acquire the seven abilities and attitudes

of (Table 1) through video co-creation. Our team de-

signed the workshop flow in four phases to acquire

these abilities and attitudes (Fig.1). We have also

set the specific abilities and attitudes that the students

will obtain within each phase (Fig.2).

Figure 2: Abilities and attitudes that aim the students toward

acquisition in each phase.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

642

3.2.1 Research Phase

Research Phase Activities.

• Research about SDGs

• Draw an illustration

In the first phase, research, students examine SDGs

to understand the issues set by SDGs. As the first

step in group collaboration, students draw a group il-

lustration that expresses concrete actions that can be

achieved based on the research results. This work is

also an exercise for the next phase: making a story-

board. In this phase, we set tasks that can be com-

pleted in a short amount of time—rather than sud-

denly making a video—so students can practice com-

munication and collaboration and gain confidence.

By letting students think about concrete actions they

can achieve, we aim for them to acquire 1.Ability to

think critically and 2.Ability to plan with anticipation

of a future scenario.

3.2.2 Planning Phase

Planning Phase Activity.

• Making a storyboard

In the second phase, the planning phase, students

make a storyboard with their group, using the in-

formation gained during the research phase to create

short videos that promote SDGs. This work aims for

students to make a feasible plan while predicting the

making phase’s progress and deadline. By creating

a storyboard to envision the video’s completion as a

group, we aim for the students to acquire 2.Ability to

plan with anticipation of a future scenario, 4.Commu-

nication skills and 5.Ability to cooperate with others.

3.2.3 Making Phase

Making Phase Activities.

• Video shooting

• Video editing

In the third phase, the making phase, students shoot

and edit videos based on the storyboard they created

during the previous phase. During this task, students

need to allocate and perform shooting and editing

tasks with group members. Through group work and

division of work, we aim for the students to acquire

4.Communication skills, 5.Ability to cooperate with

others, 6.Respectful of relations and connections and

7.Proactive participation.

3.2.4 Reviewing Phase

Reviewing Phase Activity.

• Reacting to peers’ work

In the final phase, the reviewing phase, students watch

and react (e.g., comment or push the like button) to

videos from other teams. This task aims not just to

make a video but to watch one another’s videos to

gain confidence in one’s work and gain inspiration

from other works. By looking at and reacting to other

teams’ works, we want the students to acquire 3.Mul-

tidimensional and integrative thinking and 6.Respect-

ful of relations and connections for students.

4 PRACTICE

4.1 Research Phase

In the “Research phase,” we provided students an op-

portunity to study SDGs before making videos. To

help them think about SDGs more deeply, we asked

students to pick one of the SDGs’ goals and set spe-

cific actions they can achieve as “summer vacation

promises.” We also shared“The lazy person’s guide

to saving the world”

1

with the students as a reference

for inspiration.

Our research group facilitators first explained the

work progress using Google slide, and we divided the

students into 20 groups of 5 to 6. For communication

and cooperation, we randomly formed a team regard-

less of the homeroom class. As a result, many stu-

dents joined groups with people they met for the first

time. After that, we asked each group to do the tasks

mentioned above. The students decide the “summer

vacation promise” and draw it into a single illustra-

tion on Google Jamboard (Fig.3). In the “summer

vacation promise,” the students decided on one SDG-

related activity they do during summer vacation. We

set the sharing time for after group work, so each team

gave a short presentation about the “summer vacation

promise” using the illustrations.

Figure 3: Example of “summer vacation promise” illustra-

tions.

1

https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/takeaction/

Design and Practice of ESD in High School in Japan through Online Video Co-creation Workshop

643

4.2 Planning Phase

In the “Planning phase,” the students created story-

boards as the first step in video creation for the sake of

smooth work in the later phases (when shooting and

editing the videos). At the beginning of this phase, the

facilitators gave an overview of video creation, and

the students understood that the purpose was to make

a short video to promote the SDGs. After that, but

before the students made their storyboards, we pre-

sented several existing videos as reference works.

The students made their storyboards in the same

groups on Google Jamboard as they did during the re-

search phase. A sample storyboard had already been

drawn on Google Jamboard, and the students could

work on it by replacing elements. The students could

use the storyboard to draw images of each scene, write

scene descriptions, and present dialogue or narration.

Google Jamboard can insert images directly from the

Internet. With this function, even students who are not

good at drawing can easily create storyboards (Fig.4).

At the end of the “planning phase”, we tried to share

each team’s storyboard, but sharing the storyboards

was difficult in the short time that remained, so the

facilitators took screenshots of the highlights of each

team’s storyboard. We collected them on a single

slide and shared them.

Figure 4: Example of storyboards created by students.

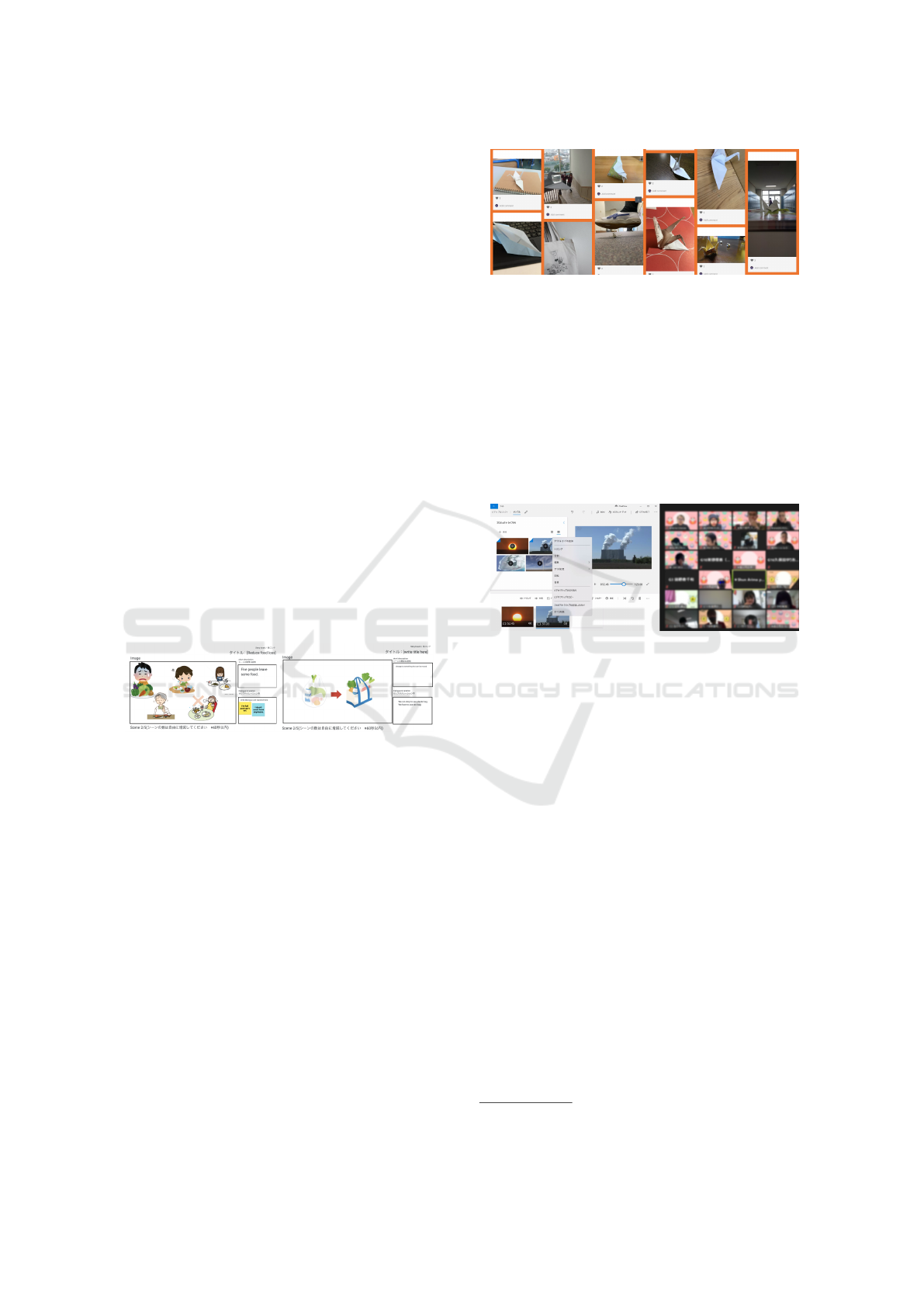

4.3 Making Phase

The “Making phase” consisted of three classes. In this

phase, the students shot and edited the video based on

the previous phase’s storyboards. As mentioned in

2. Literature Review, the students are from a genera-

tion that shoots videos with smartphones every day;

these students fully understand the culture of videos,

so we did not give a lecture on specific methods of

shooting them. Instead, as part of the icebreaker

game, we asked the students to take the biggest or

the smallest pictures of origami cranes (traditional

Japanese papercraft). These pictures were shared in

one place on the web, and the students enjoyed vari-

ous layouts (Fig.5). This icebreaker made the students

understand that the camera angle and the layout can

change the viewer’s impression of a photo (video).

Regarding the editing work, since Microsoft

Photo (a video editing software) was pre-installed on

Figure 5: Variations of origami cranes shots.

the Microsoft Surface devices owned by all students.

We held a lesson in which we provided information

on using the Microsoft Photo program by using the

Screen Sharing function on Zoom (Fig.6). In this lec-

ture, we roughly explained the operation method, and

when specific troubleshooting occurred, the facilita-

tors responded to each group. Also, we shared infor-

mation regarding some free music and sound effect

material sites so that the students had access to even

more advanced editing.

Figure 6: A scene from the editing lecture.

4.4 Reviewing Phase

In the “Reviewing phase”, the students uploaded their

completed video works on Padlet

2

, watched, and re-

acted (posting comments and pressing the “Like” but-

ton) to the video works from other teams (Fig.7). As

for the place to upload and share students’ works, we

used Padlet because Padlet has the following func-

tions: users can post comments and “like” the videos,

Padlet is similar to the existing SNS, and anyone who

has the URL can upload videos.

The Padlet was set to private and was available

only to the workshop participants and stakeholders.

When publishing works on public SNS, the high

school instructors and our team members were con-

cerned about video and music copyrights. There were

also security concerns due to the students’ faces and

homes appearing in the content—this inhibit their cre-

ativity. Therefore, we used a private Padlet for this

workshop.

Finally, all group works (20 works) were com-

pleted and uploaded to Padlet. We couldn’t watch all

the works while sharing them during class due to time

2

https://padlet.com/

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

644

constraints and the online environment’s limitations.

Hence, we asked the students to watch other teams’

projects and react (commenting, pressing the like but-

ton) as homework. Also, the facilitators watched all

the works and posted reviews on them. Having the fa-

cilitator comment first makes it easier for students to

write comments and prevents the occurrence of works

without reaction.

Figure 7: Students’ works and comments posted on Padlet.

5 FINDINGS & DISCUSSIONS

In this section, we validate whether the participat-

ing students acquired the seven abilities and attitudes

of (Table 1) in each phase, based on qualitative data

from the students’ questionnaire and observation of

the actual workshop operation. The students’ ques-

tionnaires were collected for each class in the work-

shop; they received 357 responses.

5.1 Research Phase

In the “Research phase” activities, after researching

SDGs, we provided the students with the opportunity

to consider specific and feasible actions as a “summer

vacation promise.” The following comments were re-

ceived from the students. “Because it is for future of

World, it is important for us not to give up and con-

tribute as individuals in achieving the goals.”, “I was

able to consider what to think and what to do with the

future of SDGs.”, “To reach the goals of the SDGs, it

is necessary to think about the countermeasures, im-

plement them steadily, and continue moving forward.”

These comments show that students are more than just

aware of the problem. They also have the tendency to

think positively and progressively about better solu-

tions. This is the element of 1.Ability to think criti-

cally shown in (MEXT, 2016). As the comments in-

dicate, students could plan their current actions while

understanding future issues through activities during

this phase. This suggests that students got 2.Ability to

plan with anticipation of a future scenario.

Related to the method of drawing one illustration

in a group, some students mentioned “It was easy to

exchange information by drawing a picture, and I was

able to work happily.”, and “It was exciting to draw

an illustration together.” These comments show that

there were fun activities during the promotion of in-

formation sharing for the team.

5.2 Planning Phase

Making a storyboard in the “Planning phase” gave the

students the following experiences: “It was fun to cre-

ate something together by discussing with everyone in

the group and exchanging opinions with each other.”,

“I was able to talk actively with people from different

classes.”. These comments suggested that students’

acquisition of 4.Communication skills and 5.Ability to

cooperate with others could be realized through sto-

ryboard creation. On the other hand, some indicated

communication problems peculiar to the online envi-

ronment. They included the following: “Some people

turned off their cameras and microphones, and when I

talked to them, there is no reaction or (the voice) was

faint. I did not know what to do because only some

of them responded to me...”. Such problems were

less likely to occur in the offline environment because

there was a wealth of non-verbal information. Some

improvements were needed for smoother communica-

tion in the online environment. For instance, setting a

rule to always turn on the camera during group work.

Some teams entered the “Making phase” without

completing the storyboard. The facilitators could not

grasp the video creation’s precise progress by look-

ing at the storyboard’s progress on Google Jamboard.

(Some teams had completed videos but not the story-

boards.) As a result, there were occasions when the

facilitator could not provide a team with appropriate

advice and follow-up.

About half of the teams could not complete video

creation on the originally planned schedule. The

storyboards were effective places for teams to share

ideas, but they were inadequate as time management

tools to help the teams complete the work in time.

Therefore, it can be said that making a storyboard is

not enough to contribute to the acquisition of 2.Abil-

ity to plan with anticipation of a future scenario. Stu-

dents did not have enough group video production ex-

perience, so it was difficult to predict accurately how

long each task would take. As a result, there was a de-

lay in the schedule. To ensure the work is completed

on schedule, it is important to make them aware of

where they are in the process of creating the video.

One way to do this is to create a progress check-

list or to-do list separate from the storyboard so that

facilitators and team members can accurately track

the team’s progress. A progress checklist or to-do

list will allow team members to check the remaining

Design and Practice of ESD in High School in Japan through Online Video Co-creation Workshop

645

work contents while considering the schedule. Fur-

thermore, facilitators can accurately track the work’s

progress to give students more accurate advice.

5.3 Making Phase

In the “Making phase”, we received a lot of posi-

tive feedback from the students regarding group com-

munication. For example, “I immediately put any

ideas that I came up with into words, and other mem-

bers were able to develop new ideas from them, even

though I was just rambling.”, “I learned that we can

come up with new ideas by asking people who have

not spoken yet,” and “I’m glad that each member

was able to work in their own fields, such as video

editing and ideation.” These comments suggest that

when shooting and editing videos, they have fully ex-

perienced opportunities for communication, collabo-

ration, and respect for others through the division of

roles and collaboration with other members. In other

words, the students could acquire three abilities and

attitudes: 4.Communication skills, 5.Ability to coop-

erate with others, and 6.Respectful of relations and

connections.

On the other hand, the team’s work division did

not go smoothly in some cases: “Some people in the

group did not speak, I felt burdened because only

two people were working on the video.” Therefore,

7.Proactive participation cannot be fully learned by

some students. To solve these problems, it is possi-

ble to preset the roles (e.g., director, cameraman, or

editor).

In the editing process, some students used re-

sources that exceeded our expectations. They used

familiar video editing software other than Microsoft

Photo to edit the videos within their groups. As they

go through the SNS on daily basis, some of the stu-

dents may already be familiar with the video creation

culture and tools. By gathering detailed information

about the students’ video creation experience before

conducting the workshop, we can expect to provide a

smoother video creation process.

5.4 Reviewing Phase

From watching and reacting to other teams’ works,

the students provide us with the following comments:

“Looking at the works of other teams, I got in-

spired by the way they composite their videos.” An-

other student said, “I learned about a lot of things

that we should do (regarding SDGs) by watching the

completed video.” And a third comment stated, “I

was amazed at the videos of other groups.” These

comments suggest multifaceted thinking and respect

for other teams. Watching and reviewing video

works greatly contributed to the students’ acquisition

of 3.Multidimensional and integrative thinking and

6.Respectful of relations and connections.

However, opportunities for communication

through the works were limited. It was impossible to

bring about active movements there, so it is necessary

to design more fulfilling communication time and

opportunities.

6 CONCLUSION

This paper has discussed the design and practice

of ESD through a video co-creation workshop for

Japanese high school students and explored the pos-

sibilities of video co-creation for ESD practices in

an online environment. We investigated whether the

students who participated acquired the seven abili-

ties and attitudes central to ESD through the work-

shop. As a result, it was confirmed that in each phase

of video co-creation, critical thinking and collabo-

ration abilities were acquired. Nevertheless, there

were challenges to promoting active participation and

smooth collaborative work and planning.

Although more validation is needed, this study has

also shown insights and possibilities for concrete ESD

practices feasible even in an online environment due

to COVID-19. These findings are for smooth commu-

nication and work progress by the group and can be

applied to both online and offline environments and

workshops. Furthermore, since the findings of this

paper are in a Japanese context, it is necessary to con-

sider their limitations when adapting them to other

cultures and contexts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to express our deep gratitude to

the teachers and students of FUJIMIGAOKA HIGH

SCHOOL for GIRLS for their cooperation. We also

thank the KMD Global Education Project students for

supporting the workshop, and our thanks to all of the

reviewers and volunteers.

REFERENCES

Alpay, E. and Gulati, S. (2010). Student-led podcasting

for engineering education. European Journal of En-

gineering Education, 35(4):415–427.

Azeiteiro, U. M., Bacelar-Nicolau, P., Caetano, F. J., and

Caeiro, S. (2015). Education for sustainable develop-

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

646

ment through e-learning in higher education: experi-

ences from portugal. Journal of Cleaner Production,

106:308–319.

Cayari, C. (2014). Using informal education through music

video creation. General Music Today, 27(3):17–22.

Ceulemans, K. and De Prins, M. (2010). Teacher’s manual

and method for sd integration in curricula. Journal of

Cleaner Production, 18(7):645–651.

Chau, C. (2010). Youtube as a participatory culture. New

directions for youth development, 2010(128):65–74.

Cotton, D. and Winter, J. (2010). It’s not just bits of pa-

per and light bulbs. a review of sustainability pedago-

gies and their potential for use in higher education.

Sustainability education: Perspectives and practice

across higher education, pages 39–54.

Cox, A. M., Vasconcelos, A. C., and Holdridge, P. (2010).

Diversifying assessment through multimedia creation

in a non-technical module: reflections on the maik

project. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Educa-

tion, 35(7):831–846.

Emblen-Perry, K., Evans, S., Boom, K., Corbett, W., and

Weaver, L. (2017). Evolution of an interactive on-

line magazine for students, academics and expert

practitioners, to engage students from multiple disci-

plines in education for sustainable development (esd).

In Handbook of Theory and Practice of Sustainable

Development in Higher Education, pages 157–172.

Springer.

Gilje, Ø. (2010). Multimodal redesign in filmmaking prac-

tices: An inquiry of young filmmakers’ deployment

of semiotic tools in their filmmaking practice. Written

Communication, 27(4):494–522.

Greene, H. and Crespi, C. (2012). The value of student cre-

ated videos in the college classroom-an exploratory

study in marketing and accounting. International

Journal of Arts & Sciences, 5(1):273.

Hawley, R. and Allen, C. (2018). Student-generated video

creation for assessment: can it transform assessment

within higher education? International Journal for

Transformative Research, 5(1):1–11.

Hobbs, R. and Moore, D. C. (2013). Discovering media

literacy: Teaching digital media and popular culture

in elementary school. Corwin Press.

Jaramillo, J. A. (1996). Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory and

contributions to the development of constructivist cur-

ricula. Education, 117(1):133–141.

Lambrechts, W., Mul

`

a, I., Ceulemans, K., Molderez, I., and

Gaeremynck, V. (2013). The integration of compe-

tences for sustainable development in higher educa-

tion: an analysis of bachelor programs in manage-

ment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 48:65–73.

Lohrmann, C. (2017). Online learning—do moocs con-

tribute to the goals of agenda 21:“education for sus-

tainable development”? In Sustainability in a Digital

World, pages 211–224. Springer.

Lozano, R., Barreiro-Gen, M., Lozano, F. J., and Sam-

malisto, K. (2019). Teaching sustainability in euro-

pean higher education institutions: Assessing the con-

nections between competences and pedagogical ap-

proaches. Sustainability, 11(6):1602.

Lozano, R., Merrill, M. Y., Sammalisto, K., Ceulemans, K.,

and Lozano, F. J. (2017). Connecting competences

and pedagogical approaches for sustainable develop-

ment in higher education: A literature review and

framework proposal. Sustainability, 9(10):1889.

Madden, A., Ruthven, I., and McMenemy, D. (2013).

A classification scheme for content analyses of

youtube video comments. Journal of documentation,

69(5):693–714.

MEXT (2016). A guide to promoting esd (educa-

tion for sustainable development) (first edition).

https://www.mext.go.jp/component/a\ menu/other/

\\micro\ detail/\ \ icsFiles/afieldfile/2018/04/11/

1369326\\\ 02.pdf. Accessed: 2021-03-03.

Or

´

us, C., Barl

´

es, M. J., Belanche, D., Casal

´

o, L., Fraj,

E., and Gurrea, R. (2016). The effects of learner-

generated videos for youtube on learning outcomes

and satisfaction. Computers & Education, 95:254–

269.

Pappas, E., Pierrakos, O., and Nagel, R. (2013). Using

bloom’s taxonomy to teach sustainability in multiple

contexts. Journal of Cleaner Production, 48:54–64.

Pereira, J., Echeazarra, L., Sanz-Santamar

´

ıa, S., and

Guti

´

errez, J. (2014). Student-generated online videos

to develop cross-curricular and curricular competen-

cies in nursing studies. Computers in Human Behav-

ior, 31:580–590.

Redvall, E. N. (2009). Scriptwriting as a creative, collabora-

tive learning process of problem finding and problem

solving. MedieKultur: Journal of media and commu-

nication research, 25(46):22–p.

Reimers, F. M. and Schleicher, A. (2020). A framework to

guide an education response to the covid-19 pandemic

of 2020. OECD. Retrieved April, 14(2020):2020–04.

Ryan, B. (2013). A walk down the red carpet: students

as producers of digital video-based knowledge. Inter-

national Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning,

5(1):24–41.

Schrum, K., Dalbec, B., Boyce, M., and Collini, S. (2017).

Digital storytelling: Communicating academic re-

search beyond the academy. In Innovations in Teach-

ing & Learning Conference Proceedings, volume 9.

Shewbridge, W. and Berge, Z. L. (2004). The role of

theory and technology in learning video production:

The challenge of change. International Journal on E-

learning, 3(1):31–39.

Stubbs, W. and Schapper, J. (2011). Two approaches to

curriculum development for educating for sustainabil-

ity and csr. International Journal of Sustainability in

Higher Education.

Topoklang, K., Maekawa, M. S., and Okawa, K. (2018).

Komakids: Promoting global competence through

media creation in elementary school. In CSEDU (2),

pages 443–448.

Trevors, J. T. and Saier, M. H. (2010). Education for hu-

manity. Water, air, and soil pollution, 206(1-4):1–2.

UNESCO (2014). Shaping the future we want: Un decade

of education for sustainable development; final re-

port. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/

docum\\ents/1682Shapingthefuturewewant.pdf. Ac-

cessed: 2021-01-25.

UNESCO (2020). Education for sustainable development:

a roadmap. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/

pf0000374802. Accessed: 2021-01-25.

Design and Practice of ESD in High School in Japan through Online Video Co-creation Workshop

647