Privacy by Design Enterprise Architecture Patterns

Maria Dias Coelho, Andr

´

e Vasconcelos and Pedro Sousa

INESC-ID, Instituto Superior T

´

ecnico, Avenida Rovisco Pais 1, Lisbon, Portugal

Keywords:

Privacy by Design, GDPR, Enterprise Architecture, Patterns.

Abstract:

With the fast technological evolution and globalisation, the importance of data protection increases as the

amount of data created and stored continues to grow at unprecedented rates. Organisations are encouraged

to implement technical and organisational measures at the earliest stages of the design of the processing op-

erations, in a way that ensures privacy and data protection principles right from the start. The General Data

Protection Regulation (GDPR), whose aim is to ensure EU citizens’ rights and the respect for their personal

data, addresses this topic by requiring that organisations put in place appropriate measures to implement the

data protection principles effectively. Our proposal aims to use enterprise architecture patterns to integrate

regulatory concerns, with special emphasis on the data subject’s rights. We also aim at ensuring that systems

comply with the regulation from the beginning of their definition, in light of Privacy by Design principles.

1 INTRODUCTION

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)

came into effect in 2018 and organisations dealing

with personal data were faced with numerous chal-

lenges. The obligation to comply with the regulation

has directly impacted the way organisations collect,

store and manage personal data, which poses many

challenges to organisations, meaning that they may

have to spend time, money, and effort performing ad-

ditional processes and tasks.

Enterprise architects play a crucial role in organi-

sations on achieving compliance with GDPR, provid-

ing cross-cutting analyses on the use and protection of

data across the enterprise. Furthermore, architecture

models are the major source for demonstrating this

compliance (Lankhorst, 2020). By defining enterprise

architecture patterns, a solution can be found to a re-

curring problem, and a ”best-practices”-solution can

be achieved with little effort (Buchmann and Anke,

2017).

Taking this into account, how can we ensure

GDPR compliance in a simpler, safer, and managed

way, and how can Enterprise Architecture’s Patterns

be a suitable solution? With this work, we aim at

defining and modelling Enterprise Architecture Pat-

terns that tackle the GDPR constraints regarding the

data subject’s rights. With this approach, we also sup-

port that privacy should be considered by design, a

key concept of the regulation.

The structure of the paper is the following:

Section 2 describes the most relevant concepts and

related details within the subject of this work: GDPR

and privacy by design. In this section, different ap-

proaches for ensuring compliance with the regulation

are also presented.

Section 3 presents the definition of a set of enter-

prise architecture patterns that address the rights of

the Data Subject in light of the GDPR.

Section 4 discusses the relevancy and quality of

the solution proposed and the conclusions are pre-

sented in section 5.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 GDPR Overview

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a stan-

dardized and enforceable law that regulates how per-

sonal data is managed, collected, stored, and trans-

ferred within the EU territory (Pandit et al., 2018).

This regulation is directed to any person in an organi-

sation operating within the EU that processes personal

data (Teixeira, 2021). Not only this legislation estab-

lishes requirements regarding the personal data treat-

ment, but also defines a group of rights regarding per-

sonal data subjects.

In summary, for organisations subject to the

GDPR, there are two broad categories of compliance:

Coelho, M., Vasconcelos, A. and Sousa, P.

Privacy by Design Enterprise Architecture Patterns.

DOI: 10.5220/0010473507430750

In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2021) - Volume 2, pages 743-750

ISBN: 978-989-758-509-8

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

743

data protection and data privacy. The former means

keeping data safe from unauthorized access. The lat-

ter means empowering organisation’s users to make

their own decisions about who can process their data

and for what purpose. GDPR addresses these issues

through its unified regulation, which aims at creating

a balance between the beneficial use of personal data

and the protection of individual privacy.

It is also relevant to mention the main entities

that need to be considered when analysing the GDPR.

These are defined as follows: Data Subject (an indi-

vidual or entity whose role is as a user or recipient of

a system or a service that provides consent for activ-

ities); Controller (an entity that determines the pur-

poses and means of the processing of personal data);

Processor (an entity that processes personal data on

behalf of the controller); and Supervisory Authority

(a public institution responsible for monitoring the ap-

plication of data protection laws).

2.1.1 Privacy and Data Protection Principles

The GDPR outlines six data protection principles that

summarise its requirements, which are key for ensur-

ing compliance that are set out right at the beginning

of the GDPR and both, directly and indirectly, influ-

ence the other rules and obligations found through-

out the legislation. These principles set out obli-

gations for businesses and organisations that collect,

process, and store individuals’ personal data and work

as building blocks for good data protection practices.

In (Verheijen, 2017), a summary is made regarding

the six principles, which are defined as follows:

1. The Principles of Lawfulness, Fairness, and

Transparency (Art. 7, 8, 9 GDPR): The per-

sonal data must be processed in a lawful manner,

with the data subject’s consent. The data subjects

must be informed on the reason why the data is

being processed and how.

2. The Principle of Purpose Limitation (Art. 5,

Clause 1, sub b GDPR): Personal data can only

be processed based on explicitly described and

justified objectives/reasons.

3. The Principle of Data Minimization (Art. 5,

Clause 1, sub c GDPR): Processing and collect-

ing data must be limited to what is strictly neces-

sary taking into account the objectives.

4. The Principle of Trueness, Accuracy (Art. 5,

Clause 1, sub d GDPR): Any data source must

be legitimised and in case of data inaccuracy, it

must be removed or rectified.

5. The Principle of Storage Limitation (Art. 5,

Clause 2, sub e GDPR): The data may only be

retained for a limited amount of time and as soon

as the objective of the data processing has been

achieved it must be removed.

6. The Principle of Integrity and Confidentiality

(Art. 5, Clause 1, sub f GDPR): Appropriate

technical and organisational measures to guaran-

tee suitable protection for processing the personal

data must be taken. Failure to comply may lead to

the application of fees or penalties.

Furthermore, a seventh principle can be added to the

list presented above. This principle focuses on Ac-

countability which is related to the enterprises’ re-

sponsibility in complying with GDPR and also in

demonstrating it.

2.1.2 Data Subject’s Rights

Data subject rights are one of the key areas of GDPR.

If an organisation processes its data, the regulation re-

quires that this processing meets certain obligations

regarding the data subjects (Logemann, 2020).

1. Right to be Informed: data subjects have the

right to be informed about the collection and use

of their personal data and specific privacy infor-

mation must be provided.

2. Right of Access: data subjects have the right

of access to personal data and confirmation of

whether their data is being processed. A copy of

the personal data being processed and other sup-

plementary information must be provided.

3. Right of Rectification: data subjects can ask to

erase or rectify inaccurate or incomplete data.

4. Right to Erasure: individuals have the right

to ask to delete their personal data if their data

have been processed unlawfully or it is no longer

needed for the original purpose or their consent is

withdrawn.

5. Right to Restrict Processing: individuals can

ask you to restrict processing their personal data

if, for instance, they believe their data is not accu-

rate or the processing is unlawful but the individ-

ual doesn’t want the data erased.

6. Right to Data Portability: individuals are al-

lowed to obtain and reuse their personal data for

their purposes across different services.

7. Right to Object: individuals have the right to ob-

ject to their personal data processing if its lawful

bases are of public interest or legitimate interests.

8. The Rights Concerning Automated Decision

Making and Profiling: individuals have the right

not to be subject to a decision that is based solely

on automated processing.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

744

2.2 Privacy by Design

In the digital world, privacy plays a crucial role. It

is imperative to create a balance between data pro-

cessing entities, which determine what and how data

is processed, and the individuals whose data is at

stake, which are most of the time unaware of the

data processing and its consequences. Privacy is all

about control, enabling individuals to maintain per-

sonal control over their personally identifiable in-

formation, concerning its collection and disclosure

(Cavoukin and Dixon, 2013; Danezis et al., 2014).

Nowadays, our society depends more on the trust-

worthy functioning of information and communica-

tion technologies. However, unclear responsibilities

and lack of transparency in the development of these

technologies lead to the lack of guarantees of privacy

and security features (Danezis et al., 2014). Conse-

quently, taking into account that privacy needs to be

addressed from the beginning of the system develop-

ment, the concept Privacy by Design was defined.

Privacy by design (PbD) is a concept that was

coined in 1997 by the Canadian privacy expert

and Commissioner of Ontario, Canada, Dr. Ann

Cavoukian and aims to embed privacy into the design

of systems or products from the start of their develop-

ment, and throughout all stages of its lifecycle: col-

lection, processing, disclosure, storage and disposal

(Okoye, 2017). In fact, the application of PbD cuts

across the entire structure of a business or organ-

isation, including its information technology, busi-

ness practices and processes, physical design and net-

worked infrastructure (Cavoukin and Dixon, 2013).

2.2.1 Principles

Ann Cavoukian developed seven fundamental princi-

ples of PbD aiming at establishing a universal frame-

work for the strongest protection of privacy available

in the modern era (Cavoukian, 2011). Although they

are not detailed enough to allow the direct application

or engineering into systems, they can serve as a refer-

ence model. In (Cavoukian, 2011), the seven princi-

ples are described as follows:

1. Proactive not Reactive; Preventative not Reme-

dial: The PbD approach aims at anticipating and

preventing privacy-invasive events before they oc-

cur, rather than taking reactive measures.

2. Privacy as the Default: PbD seeks to deliver the

maximum degree of privacy by ensuring that per-

sonal data is automatically protected in any given

IT system or business practice. This principle

is guided by the standards: Purpose Specifica-

tion, Collection Limitation, Data Minimisation

and Use, Retention and Disclosure Limitation.

3. Privacy Embedded into Design: Privacy must be

embedded into the design and architecture of IT

systems and business practices in a holistic, inte-

grative, and creative way due to the fact that ad-

ditional contexts must always be considered, all

stakeholders and interests should be consulted and

existing choices re-invented.

4. Full Functionality - Positive-Sum, not Zero-Sum:

PbD seeks to accommodate all legitimate inter-

ests and objectives in a positive-sum ”win-win”

manner, rather than a dated, zero-sum approach,

where unnecessary trade-offs are made.

5. End-to-End Security - Lifecycle Protection:

PbD having been embedded into the system prior

to the first element of information being collected,

extends securely throughout the entire lifecycle of

the data involved, which ensures secure lifecycle

management of information, end-to-end.

6. Visibility and Transparency: PbD seeks to assure

all stakeholders, operating according to the stated

promises and objectives, subject to independent

verification, which is imperative in establishing

accountability and trust. This principle places

special emphasis in the following standards: Ac-

countability, Openness and Compliance.

7. Respect for User Privacy: PbD requires archi-

tects and operators to keep the interests of the

individual uppermost by offering measures such

as strong privacy defaults, appropriate notice, and

empowering user-friendly options, which is sup-

ported by the following standards: Consent, Ac-

curacy, Access, and Compliance.

2.2.2 Privacy Patterns

Privacy patterns work as central building blocks for

ensuring the correct translation from legal require-

ments into technological solutions. This translation

assures that systems conform to privacy regulations,

and consequently guarantees privacy by design.

In (Doty, 2013), possible directions for how

the community should document patterns and anti-

patterns to improve future designs are provided, with

special emphasis on privacy patterns. In this study,

it is stated that ”privacy patterns that span across us-

ability, engineering, security, and other considerations

can provide shareable descriptions of generative solu-

tions to common design contentions.”. In (Colesky

and et al., 2021), a collection of privacy patterns

is provided, helping in the documentation of com-

mon practices/solutions to privacy problems and in

the standardization of terminology.

Privacy by Design Enterprise Architecture Patterns

745

In (Diamantopoulou et al., 2017), five basic pri-

vacy patterns are defined in order to better under-

stand the concepts regarding privacy that need to

be addressed when designing privacy-aware systems.

This article intended to provide a general template

for privacy patterns that could be used to describe

other patterns. These are briefly described as follows:

Anonymity (a characteristic that does not allow PII

to be identified directly or indirectly); Pseudonymity

(an alias is used instead of PII); Unlinkability (use

of a resource or a service by a user without a third

party being able to link the user with the resource or

service); Undetectability (inability of a third party to

distinguish who is the user); and Unobservability (

inability of a third party to observe if a user is using a

resource or a service).

2.2.3 Privacy by Design in the GDPR

The GDPR provides useful indications with regard

to objectives and evaluations of the Privacy by De-

sign process, including data protection impact assess-

ment, accountability, and privacy seals. The regula-

tion refers to the terms ”privacy by design” and ”data

protection by design” as synonyms.

As stated in Article 25 (”Data Protection by design

and by default”) (Logemann, 2020), organisational

and technical measures to realise data protection and

information security should be designed in an effec-

tive manner to enforce privacy principles. With this

article, the regulation obligates those entities respon-

sible for the processing of personal data to implement

appropriate measures and procedures both at the time

of the determination of the means of processing and at

the time of the processing itself (Danezis et al., 2014).

2.3 Ensuring Compliance with GDPR

Organisations need to ensure compliance with GDPR

and are required to demonstrate it. In fact, enterprise

architects have a uniquely broad and integrated view

of their organisation, and have the models and tools

at their disposal to assess, improve, and assure data

protection (Lankhorst, 2020). Successfully integrat-

ing GDPR in a company requires a lot of architec-

tural work. Enterprises need to be completely aware

of their legal requirements, having transparency about

their storing, processing, and sharing of personal data,

and understanding the existing relationships along

with their enterprise architecture (Burmeister et al.,

2019; Mon

´

e, 2018). Moreover, through enterprise ar-

chitecture modelling, privacy by design is enabled in

a way that transparency about interconnections of a

organisations’ systems and the data flows along the

application development lifecycle is ensured.

2.3.1 Enterprise Architecture Models for GDPR

Compliance

Enterprise Architecture Models represent a relevant

solution for modelling a global viewpoint of GDPR

due to the fact that they embed principles that can be

related to regulatory aspects and offer different per-

spectives, such as the regulative perspective, which is

of particular interest for modelling this solution. Fur-

thermore, by having the regulation formalised as an

architectural fragment, its integration into an existing

architecture is simplified.

In (Blanco-Lain

´

e et al., 2019), a reference archi-

tecture that depicts the principles of the GDPR was

developed. In the mentioned paper, in order to pro-

vide a global viewpoint of the GDPR in terms of

the rights and requirements it conveys, several Archi-

Mate models were implemented, such as a Motivation

View, Requirements and Business Service Views, and

Deliverable viewpoints, which can be reused by any

organisation for GDPR compliance. In these models,

the two main areas in terms of regulatory obligations

highlighted in the GDPR (compliance and account-

ability) are represented as drivers. These two drivers

give rise to goals, which correspond to the seven prin-

ciples of the regulation, which are then refined into

outcomes and requirements.

In fact, the analysis made in the mentioned work is

of extreme relevance. However, since it only focuses

on the motivational and business layers, it may have

lack of specificity.

2.3.2 Business Process Models for GDPR

Compliance

To achieve compliance with GDPR, the regulation

enforces organisations to reshape the way they ap-

proach the management of personal data stored and

exchanged during the execution of their everyday

business processes.

In (Agostinelli et al., 2019), a set of design

patterns to integrate privacy-enhancing features in

a BPMN model according to GDPR is proposed.

This approach enables an effective representation of

design-time solutions to tackle GDPR constraints in

BP models and consequently achieving compliance.

In the mentioned research, the following seven pri-

vacy patterns to capturing and integrating the con-

straints in GDPR in business process models are rep-

resented in BPMN: Data Breach, Consent to Use the

Data, Right to Access, Right of Portability, Right to

Withdraw, Right to Rectify, Right to be Forgotten (see

Fig. 1). Even though this approach is of extreme rele-

vance, it only focuses on the Data controller’s obliga-

tions.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

746

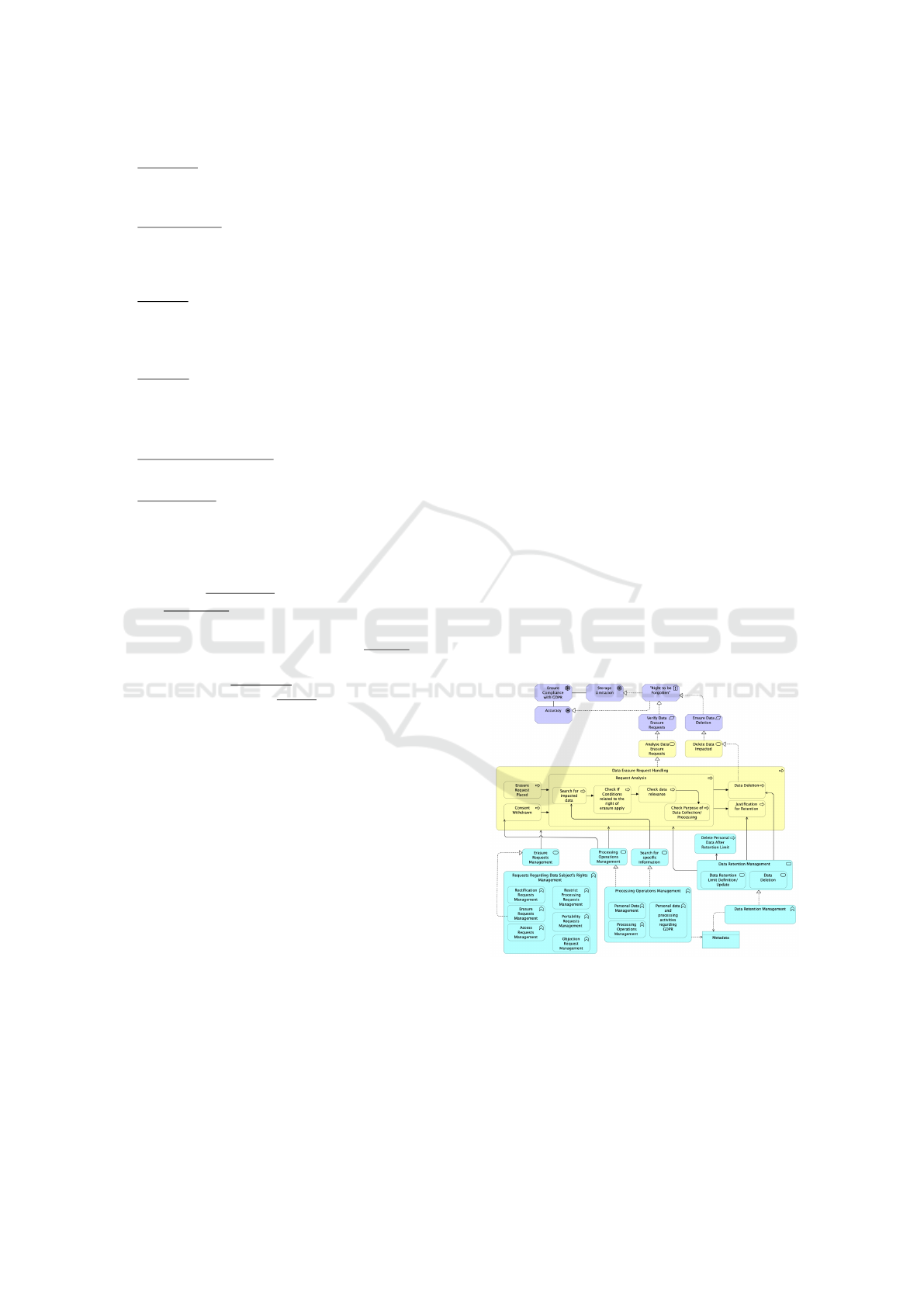

Figure 1: BPMN model for pattern Right to be Forgotten

(Agostinelli et al., 2019).

3 PATTERNS FOR THE DATA

SUBJECT’S RIGHTS

Organisations are required to implement correctly the

GDPR data management policies and take appropri-

ate actions on data when requested by their customers.

Furthermore, the impact on the information system of

an organisation, from the motivation layer to the ap-

plication and technological layers, is significant, tak-

ing into account the GDPR constrains activities in

terms of data and their processing.

In this section, we propose a first version of two

patterns concerning the data subject’s rights.

3.1 Structure

3.1.1 Chosen Patterns and Template

In this work, we propose a first version of Enterprise

Architecture Patterns to tackle specific requirements

from the GDPR, regarding the data subject’s rights,

which can be reused by organisations to help them

achieve compliance. The patterns developed aim at

integrating privacy-enhancing features in an Enter-

prise Architecture since privacy should be introduced

by design.

The patterns proposed are the following:

1. Right to be Forgotten: Pattern that ensures that the

requests for personal data erasure are handled.

2. Right to Rectify: Pattern that ensures that the re-

quests regarding rectification or completion of

personal data are handled.

The five remaining rights of the data subject in light

of the regulation follow the same rationale as the pro-

posed patterns. Their definition is not presented here

so that we could explain in detail how the proposed

patterns can be applied and their relevance evaluated.

According to Perroud, T. and Inversini, R. (Per-

roud and Inversini, 2013), patterns are defined by in-

troducing a solution scheme/template that contains:

the name; the problem; the context; the forces govern-

ing the pattern; the solution; the consequences arising

when using this pattern; and the resulting context.

The definition of the proposed patterns is made ac-

cording to a template, which structure follows the ap-

proach of Clara Teixeira et al (Teixeira, 2021). This

template is organised using the following fields:

• Associated GDPR Principle: The GDPR require-

ments that the patterns aim to solve.

• Name: Pattern’s Name.

• Context: Under what circumstances the pattern is

applicable and what the preconditions are that an

enterprise must fulfill in order to use this pattern.

• Problem: Describes the problem that should be

solved in greater detail.

• Solution: Vision, views and principles describing

the solution for the problem. In our case, an En-

terprise Architecture Model will be illustrating the

solution alongside with its description.

• References:

Source or further related information.

3.1.2 Definition Specifications

The proposed patterns definition is illustrated as an

ArchiMate Model, a visual language with a set of de-

fault iconography for describing, analyzing, and com-

municating many concerns of Enterprise Architec-

tures. It supports modelling the regulation as an archi-

tecture and enables its incorporation within an actual

enterprise architectural model, hence its relevancy for

our work. There are three levels at which an enterprise

architecture can be modeled in ArchiMate - Business,

Application, and Technology, distinguished by their

corresponding colours - Yellow, Blue, and Green. In

the proposed models, it is used the colour yellow (en-

compassing business services, which are realized in

the organization by business processes), as well as the

colour blue (encompassing application services that

support the business, and the applications that realize

them). Additionally, ArchiMate provides other nota-

tion cues to represent other elements, such as the Mo-

tivation ones, defined as reasons that guide the design

of an Enterprise Architecture. These elements are also

incorporated in our diagrams in the colour purple.

The concepts that compose the diagrams are the

following (The Open Group, 2021):

• Driver: condition that motivates an organization to

define its goals and implement the changes neces-

sary to achieve them. In our work, it is defined by

the need to comply with the regulation.

• Goal: a high-level statement of intent or desired

end state. In our work, it represents the GDPR

requirements the pattern aims to comply to.

Privacy by Design Enterprise Architecture Patterns

747

• Principle: a statement of intent defining a general

property that applies to any system. In our work,

it is represented by the pattern itself.

• Requirement: a statement of need defining a prop-

erty that applies to a specific system. In our work,

it is defined by the properties that need to exist to

realize the principle.

• Service: a explicitly defined behavior. In our

work, we use both business and application ser-

vices, representing the behaviour in that specific

layer.

• Process: a sequence of behaviors that achieves a

specific result. In our work, we use both busi-

ness and application processes, representing the

behaviour in that specific layer.

• Application Function: automated behavior that

can be performed by an application component.

• Data Object: Represents data structured for auto-

mated processing. In our work, it is named as

Metadata, where all the organisation data and data

regarding processing operations is encompassed.

The relationships, which connect these concepts are

the following: association (associating the goal to the

driver); realization (representing that an entity plays a

critical role in the creation, achievement, sustenance,

or operation of a more abstract entity); serving (rep-

resenting that an element provides its functionality to

another element); triggering (illustrating the flow of

business behaviors); and access (illustrating the ac-

cess from the application functions to a data object).

3.2 Patterns Definition

3.2.1 Right to be Forgotten

Associated GDPR Principles: The Principle of Stor-

age Limitation and the Principle of Trueness and Ac-

curacy.

Name: Right to be Forgotten.

Context: The right to be forgotten states that the data

subject has the right to obtain the erasure of personal

data concerning him or her, which must be erased

without undue delay if one of several conditions ap-

plies (Logemann, 2020), such as if, for instance, the

personal data is being processed unlawfully. On the

other hand, in some situations a organisation’s right

to process someone’s data might override their right

to be forgotten.

Problem: When an erasure request is placed, the or-

ganisation needs to have the right processes in place

to handle it without undue delay and have the appro-

priate methods to erase the information requested.

Solution: The representation of the pattern can be

seen in Fig. 2. The principle ”Right to be forgotten”

requires the verification and analysis of data erasure

requests and the deletion of impacted data. So han-

dling this type of request is modeled through a se-

quence of behaviours - when a request for data era-

sure is placed or the consent for data processing is

withdrawn, the data related to the request needs to

be retrieved and its relevance and purpose checked.

Furthermore, the conditions in which the erasure is

requested need to be evaluated. Finally, if all the con-

ditions are met, the data is deleted. If not, the reason

why the data cannot be deleted is communicated to

the data subject. At the application level, three main

services serve the processes described, which are re-

alised by the corresponding functions: the Erasure

Requests Management (which corresponds to the be-

haviour of handling this specific requests); the Pro-

cessing Operations Management (which represents

the behaviour of analysing the conditions in which

the data is being processed); and the Data Retention

Management (which responsible for ensuring that the

retention period is set and updated according to the

evolution of the regulation or the information system.

Its relevance for this specific principle lies on the im-

portance of limiting the data retention time and of en-

suring the deletion of data.

References: (Logemann, 2020; Blanco-Lain

´

e et al.,

2019; Agostinelli et al., 2019).

Figure 2: Right to be Forgotten Pattern.

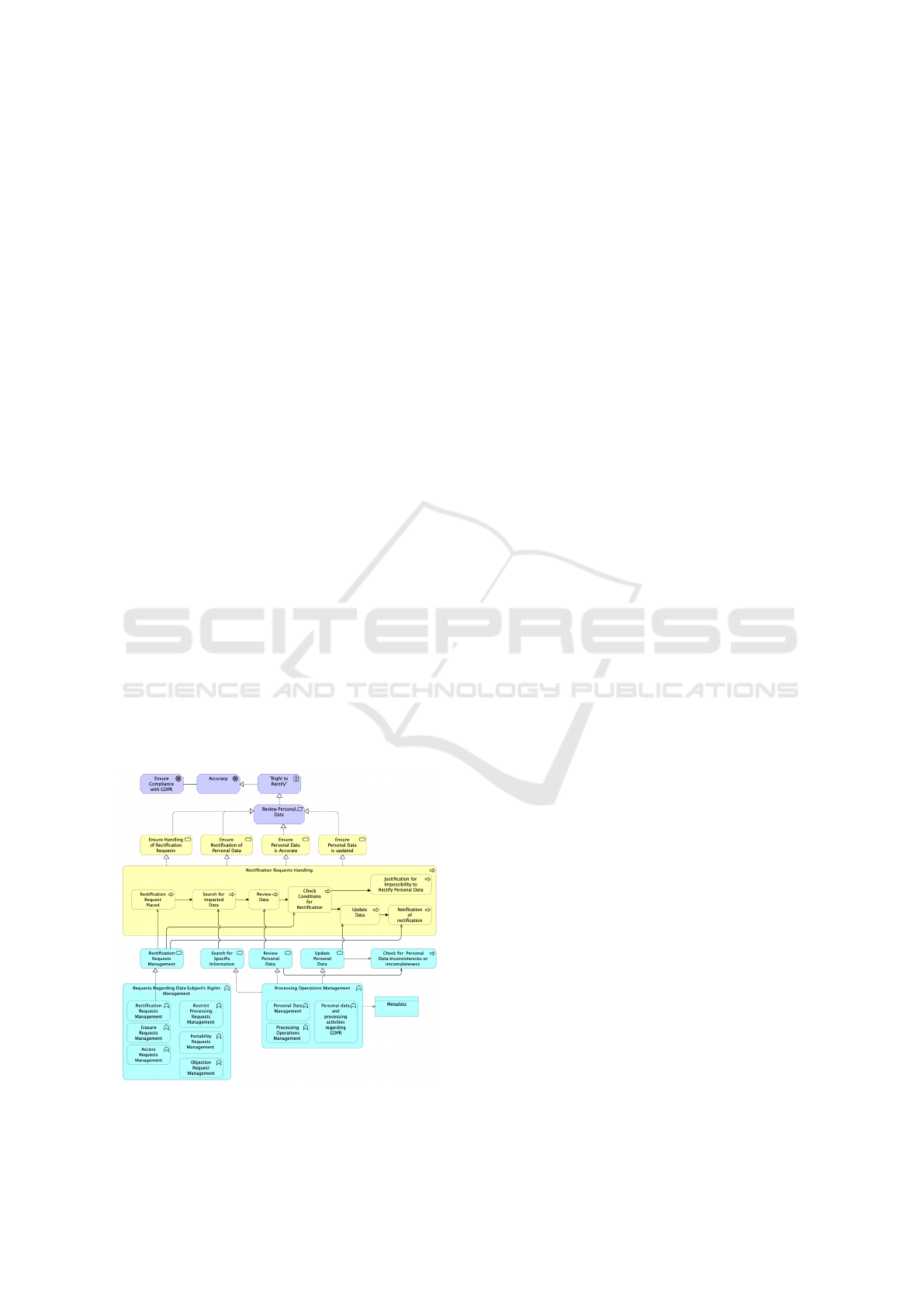

3.2.2 Right to Rectify

Associated GDPR Principles: The principle of

Trueness and Accuracy.

Name: Right to Rectify.

Context: Individuals can have inaccurate personal

data rectified, or completed if it is incomplete (Loge-

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

748

mann, 2020). In certain circumstances, the organisa-

tion can refuse a request for rectification, for instance,

if the data subject wants to rectify his social security

number, which is specific to each individual and can-

not be rectified.

Problem: Organisations must ensure that processes

are in place to timely respond to these requests and

that systems are prepared to rectify or complete the

information requested. Furthermore, the systems

should review data and check for inconsistencies or

incompleteness of personal data.

Solution: The representation of the Pattern can be

seen in Fig. 3. The principle Right to Rectify requires

the review of personal data and the handling of this

type of requests. The handling of this request is mod-

eled through a sequence of business processes illus-

trating the following behaviour - when a request for

data rectification is placed, the data impacted by the

request is reviewed and the conditions for its applica-

tion checked. If an exception occurs and the personal

data cannot be rectified, the process ends and the data

subject is notified of the reasons for the decision. If

everything is in place, the data is updated and the data

subject notified of the rectification. At the application

level, two main services serve the processes described

and that are realised by the corresponding functions -

the Rectification Requests Management (which cor-

responds to the behaviour of handling this type of re-

quests); and the Processing Operations Management

(which represents the behaviour of reviewing and up-

dating the data, as well as analysing if the conditions

to rectify the data are in place).

References: (Logemann, 2020; Blanco-Lain

´

e et al.,

2019; Agostinelli et al., 2019).

Figure 3: Right to Rectify Pattern.

4 DISCUSSION AND FUTURE

WORK

Having defined the patterns, it is now crucial to un-

derstand how can their relevance and validity be as-

sessed, as well as how will they be applied.

These patterns integrate not only in existing archi-

tectures, but also in new systems where the patterns

can be incorporated from the beginning of the sys-

tems’ development. For this reason, and since they

translate the privacy concerns into technical elements,

they can ensure privacy by design. By using appli-

cational functions in the models proposed (such as

the Requests Regarding Data Subject’s Rights Man-

agement Function and the Data Retention Manage-

ment Function) we are representing automated behav-

ior that can be performed by an application compo-

nent and, in fact, this behaviour answers to the GDPR

constraints. For instance, the Data Retention Manage-

ment Function assures the personal data is only kept

for a specified retention limit, showing compliance to

the GDPR requirement of Storage Limitation. Con-

sequently, we are embedding the GDPR compliance

into the architecture.

Taking into account the complexity of the GDPR,

the patterns proposed provide structure and organisa-

tion in ensuring compliance with the regulation, and

can also be easily adapted and integrated into an ex-

isting architecture. They help designers identify and

address privacy concerns in a simpler and managed

way. On the other hand, it is also important to take

into account the technical issues that may arise from

storing and managing data when integrating data pro-

tection and privacy, such as if the organisation is able

to get visibility into all the data they process.

The assessment of the proposed patterns is a on-

going research. We expect to address two types of

projects, in order to evaluate the quality and feasibil-

ity of our approach. First, we will analyse an existing

architecture that represents good-practices in terms of

implementation of GDPR requirements and analyse

how the data subject’s rights are ensured in their sys-

tems. With this, we aim to further develop our so-

lution so that we ensure that the GDPR requirements

are met through our solution. On a second stage, we

expect to participate in projects where the GDPR re-

quirements regarding the data subject’s rights have

not been covered yet. So, the feasibility of our ap-

proach can be demonstrated in a way that it is possi-

ble to compare the time an enterprise architect takes

to implement the GDPR requirements with and with-

out our proposal into account. Thus, the benefit of

our patterns in terms of time-saving and quality when

developing a system can be assessed.

Privacy by Design Enterprise Architecture Patterns

749

5 CONCLUSION

GDPR compliance can be complex, costly, and dis-

ruptive as organisations invest the time and resources

needed to update systems and processes to the secu-

rity level the regulation requires. Nonetheless, data

protection is crucial in an era where data is eas-

ily acquired and processed without the data subject’s

knowledge and consent (Teixeira, 2021). Understand-

ing what needs to be done in order to become compli-

ant can be challenging and even though the regulation

provides guidelines, ensuring all the requirements are

met can be demanding.

In this work, we developed a group of patterns fo-

cusing on ensuring that the data subject’s rights are

met in light of the GDPR through the modelling of

enterprise architecture patterns to be integrated into

an architecture. By using patterns we provide a com-

mon solution using motivations, services, processes,

and functions that organisations have to deal with and

integrate to be compliant. This paper proposes a set

of patterns that addresses the following GDPR use

cases:: Right to be Forgotten and Right to Rectify.

This first approach focuses on identifying the neces-

sary components, processes and flows within a sys-

tem to achieve compliance with requirements regard-

ing the data subject’s rights with special emphasis on

the business and application layers.

As future work, propose to assess the solution

based on the analysis of practical cases, which will

be of extreme relevance to evaluate the quality and

feasibility of the patterns.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by national funds through

Fundac¸

˜

ao para a Ci

ˆ

encia e a Tecnologia (FCT) with

reference UIDB/50021/2020 and by the European

Commission program H2020 under the grant agree-

ment 822404 (project QualiChain).

REFERENCES

Agostinelli, S., Maggi, F., Marrella, A., and Sapio, F.

(2019). Achieving gdpr compliance of bpmn process

models. In Information Systems Engineering in Re-

sponsible Information Systems, pages 10–22.

Blanco-Lain

´

e, G., Sottet, J.-S., and Dupuy-Chessa, S.

(2019). Using an enterprise architecture model for

gdpr compliance principles. In The Practice of Enter-

prise Modeling, 12th IFIP Working Conference, pages

199–214.

Buchmann, E. and Anke, J. (2017). Privacy patterns in busi-

ness processes. In Proceedings of 47th Jahrestagung

der Gesellschaft f

¨

ur Informatik.

Burmeister, F., Drews, P., and Schirmer, I. (2019). A

privacy-driven enterprise architecture meta-model for

supporting compliance with the general data protec-

tion regulation. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii In-

ternational Conference on System Sciences (HICSS),

volume 52.

Cavoukian, A. (2011). Privacy by design – the 7 founda-

tional principles. Technical report, Information and

Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, Canada.

Cavoukin, A. and Dixon, M. (2013). Privacy and security

by design: An enterprise architecture approach. Tech-

nical report, Information and Privacy Commissioner,

Canada.

Colesky, M. and et al. (2016 (accessed January 2, 2021)).

Privacy Patterns. https://privacypatterns.org/patterns/

Protection-against-tracking.

Danezis, G., Domingo-Ferrer, J., Hansen, M., Hoepman, J.-

H., M

´

etayer, D., Tirtea, R., and Schiffner, S. (2014).

Privacy and Data Protection by Design - from Policy

to Engineering. European Union Agency for Network

and Information Security (ENISA).

Diamantopoulou, V., Kalloniatis, C., Gritzalis, S., and

Mouratidis, H. (2017). Supporting privacy by design

using privacy process patterns. In Proceedings of IFIP

International Information Security Conference, pages

491–505.

Doty, N. (2013). Privacy design patterns and anti-patterns

patterns misapplied and unintended consequences.

Lankhorst, M. (2017 (accessed September 10, 2020)). 8

Steps Enterprise Architects Can Take to Deal with

GDPR. https://bizzdesign.com/.

Logemann, T. (2018 (accessed November 19, 2020)). Gen-

eral Data Protection Regulation - GDPR. https://

gdpr-info.eu.

Mon

´

e, L. (2018). Mastering the gdpr with enterprise archi-

tecture. Technical report, LeanIX GmbH, Germany.

Okoye, J. N. (2017). Privacy by design. Master’s the-

sis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology,

Norway.

Pandit, H. J., O’Sullivan, D., and Lewis, D. (2018). Gdpr

data interoperability model. In Proceedings of 23rd

EURAS Annual Standardisation Conference.

Perroud, T. and Inversini, R. (2013). Enterprise Archi-

tecture Patterns: Practical Solutions for Recurring

IT-Architecture Problems Patterns. Springer-Verlag

Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, 1st edition.

Teixeira, C. (2021). Enterprise architecture patterns for gdpr

compliance, information systems and computer engi-

neering. Master’s thesis, Instituto Superior T

´

ecnico,

Lisbon University.

The Open Group (2012 (accessed February 25, 2021)).

ArchiMate® 3.1 Specification. https://pubs.

opengroup.org/architecture/archimate3-doc/toc.html.

Verheijen, R. (2017). Whitepaper: Data Pro-

tection: Compliance is a Top-Level Sport.

Netherlands. https://www.exin.com/whitepaper/

data-protection-compliance-top-level-sport.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

750