Preference for Multiple Choice and Constructed Response Exams for

Engineering Students with and without Learning Difficulties

Panagiotis Photopoulos

1a

, Christos Tsonos

2b

, Ilias Stavrakas

1c

and Dimos Triantis

1d

1

Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, University of West Attica, Athens, Greece

2

Department of Physics, University of Thessaly, Lamia, Greece

Keywords: Multiple Choice, Constructed Response, Essay Exams, Learning Difficulties, Power Relations.

Abstract: Problem solving is a fundamental part of engineering education. The aim of this study is to compare

engineering students’ perceptions and attitudes towards problem-based multiple-choice and constructed

response exams. Data were collected from 105 students, 18 of them reported to face some learning difficulty.

All the students had an experience of four or more problem-based multiple-choice exams. Overall, students

showed a preference towards multiple-choice exams although they did not consider them to be fairer, easier

or less anxiety invoking. Students facing learning difficulties struggle with written exams independently of

their format and their preferences towards the two examination formats are influenced by the specificity of

their learning difficulties. The degree to which each exam format allows students to show what they have

learned and be rewarded for partial knowledge, is also discussed. The replies to this question were influenced

by students’ preference towards each examination format.

1 INTRODUCTION

Public universities are experiencing budgetary cuts

manifested in increased flexible employment,

overtime working and large classes (Parmenter et al.

2009; Watts 2017). Public Higher Education

Institutions are subject to pressures to accomplish

“more with less”. Technology is considered as a

vehicle for cost effective interventions and university

teachers adopt technology mediated solutions in order

to do more with less (Graves, 2004). In that respect,

they respond to the difficulties arising from big

classes (Scharf & Baldwin, 2007) using computer-

assisted assessment. Computer-assisted assessment

(CAA) is widely used, usually in conjunction with

multiple-choice (MC) and true/false questions, to

make student assessment easier, faster and more

efficient (Bull & McKenna, 2004). For constructed

response (CR) or essay exams students have to

construct their own answers, state assumptions, make

interpretations and critically analyse the questions

stated in the exam paper. Grading CR exams is a time

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7944-666X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8372-7499

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8484-8751

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4219-8687

consuming process and a computer-based evaluation

of the answers is still problematic (Ventouras et al.

2010).

Assessment embodies power relations between

institutions, teachers and students (Tan, 2012; Holley

and Oliver, 2000). Paxton (2000) points out that MC

exams disempower students because they are not

given the opportunity to express the answer in their

own words and construct their own solutions.

Proficiency in a certain field is demonstrated with the

selection of the correct answer, which has been

predetermined by the tutor therefore, MC exam

answers do not manifest the original effort of the

examinee. MC exams reinforce the idea that original

interpretations, and engagement in critical thinking

are not expected by the students. By limiting the

choice of options, MC exams disturb the power

relation between the student and the assessor in

favour of the latter (Paxton, 2000).

Although multiple-choice exams have become a

popular way for assessment, students with learning

difficulties (LDs) face particular problems with this

220

Photopoulos, P., Tsonos, C., Stavrakas, I. and Triantis, D.

Preference for Multiple Choice and Constructed Response Exams for Engineering Students with and without Learning Difficulties.

DOI: 10.5220/0010462502200231

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2021) - Volume 1, pages 220-231

ISBN: 978-989-758-502-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

examination format (Trammell, 2011). Extra time is

an adjustment granted to students with LDs in order

to ensure that differences in scores reflect different

levels of learning and they are not influenced by

student’s speed to provide an answer (Duncan &

Purcell, 2020). An optional oral examination

complementing the written examination, is offered to

students facing certain types of learning difficulties in

order to assure that these students are not

disadvantaged in relation to the rest of the students

(UNIWA, 2020). The degree to which such

amendments compensate for the effects of the LDs is

still in question (Gregg & Nelson, 2012). MC exams

require the exercise of faculties like memory and

recall, text comprehension, managing cognitive

distractions, holding information in short term

memory for active comparisons in which students

with LDs are rather vulnerable (Trammell, 2011;

Duncan & Purcell, 2020).

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

Issues related to MC exams like fairness, easiness,

anxiety and performance have been the subject of

numerous publications (Pamphlett & Farnill 1995;

Núñez-Peña & Bono, 2020; Simkin & Kuechler

2005). Nonetheless, research on the preference and

the attitudes of students towards MC or CR formats is

rather limited (Gupta, 2016; Kaipa, 2020). In one of

the first publications, Zeidner (1987) studied the

attitudes and dispositions toward essay versus MC

type exams on a sample of 174 students of the

secondary education. The students were also asked to

compare essay and MC formats along the following

dimensions: relative ease of preparation, actual

knowledge, expectancy of success, degree of fairness,

degree of anxiety and overall preference for each

format. The research concluded that MC exams are

perceived more favourably compared to CR exams.

Similarly, Tozoglu et al. (2004), used a 30 item

questionnaire to evaluate students’ preference on the

two examination formats along 10 dimensions: their

experience with the two exam formats, success

expectancy, knowledge, perceived facility, feeling

comfortable with the format, perceived complexity,

clarity, trickiness, fairness and perceived anxiety. In

a recent survey 65.5% of the respondents expressed a

preference for MC exams because they consider them

to be easier to take and because they could guess

better compared to CR exams (Kaipa, 2020).

The comparison between the two examination

formats usually revolves around the questions of

easiness, stress and anxiety, fairness, learning,

constructing a solution or collecting an answer and

guessing.

Easiness: Chan & Kennedy (2002) compared the

performance of 196 students on MC questions and

“equivalent” CR questions and found that students

scored better on MC examination. According to

Simkin and Kuechler, the question of easiness has

rather to do with the perceived ability of the students

to perform better on MC rather than CR exams

(Simkin & Kuechler 2005, p.76). Another aspect

related to easiness has to do with student’s

preparation. Schouller (1998) compared the studying

methods and the preparation of the students for the

two examination formats for the same course. The

research concluded that students were more likely to

employ surface learning approaches when prepared

for a MC exam and deep learning approaches when

prepared for an essay examination.

Emotional response: Anxiety in MC exams has

been studied in respect to negative marking

(Pamphlett & Farnill 1995), and more recently, as a

relationship between math-anxiety and performance

(Núñez-Peña & Bono, 2020). Students with high test

anxiety have a positive attitude toward multiple-

choice exams, while those with low test anxiety show

a preference for essay exams (van de Watering et al.

2008). High levels of stress and anxiety are also

experienced by students with learning difficulties

when coping with MC exams (Trammell, 2011)

Fairness: Students perceive MC exams to be free

of tutor intervention, therefore being more objective

and fairer (Simkin & Kuechler 2005 p.4). Emeka &

Zilles (2020) in their research found that students

expressed concerns about fairness not in relation to

whether they had received a hard version of the exam

but in relation to their overall course performance.

Students with learning difficulties face additional

difficulties with MC exams, related to problems with

short-term memory, reading comprehension and

visual discriminatory ability (Trammell, 2011)

Surface learning: Entwistle & Entwistle (1992), in

a qualitative research examined the nature of

understanding that underlies academic studying and

identified different types of revision studying which

correspond to various levels of understanding.

Preparation for the exams, studying and learning is

influenced by the type of exam. Some research

findings indicate that MC exams are related to

memorization and/or detailed but fragmented

knowledge, while CR exams are more closely related

Preference for Multiple Choice and Constructed Response Exams for Engineering Students with and without Learning Difficulties

221

to concept learning (Martinez, 1999; Biggs et al.

2001; Schouller 1998, Bull & McKenna, 2004).

Make learning demonstrable: Problem solving is

central in STEM education (Adeyemo, 2010).

Problem solving in Physics and Engineering proceeds

in stages, therefore the number-answer is usually a

poor indicator of student’s abilities and learning. In

this respect engineering students may feel in a weak

position when they are given a problem in the form of

a MC item, since they are not given the opportunity

to make their knowledge demonstrable. In

Engineering studies the construction of student’s

response is important not the answer itself (Gipps,

2005).

Express understanding in own words: Despite

Paxton’s findings that the students would have a

better performance had they been asked to give the

answer in their own words, Lukhele et al. (1994)

concluded that CR exams, although more time

consuming and of greater cost, provide less

information on students’ learning compared to MC

ones. They found that CR or open-ended questions

are superior when specific skills are assessed such as

proficiency in algebraic operations, although both

MC and CR formats demonstrated remarkably similar

correlation patterns with students’ grades (Bridgeman

1992).

The opportunity to give the correct answer by

guessing: One of the drawbacks of MC examinations

is answering by guessing, where the examinees can

increase the probability for successful guessing by

eliminating a number by distractors (Bush, 2001).

This is one of the reasons hampering the wider

employment of the MC examinations (Scharf &

Baldwin, 2007). In order to alleviate this problem

various strategies have been proposed (McKenna,

2018; Scharf and Baldwin 2007), including “paired”

MC method (Ventouras et al, 2011; Triantis et al,

2014).

3 PROBLEM-BASED MC EXAMS

Problem solving is a fundamental part of studying

physics and engineering (Redish, 2006). At a

cognitive level problem solving comprises the phases

of representation and solution (Duffy et al. 2020). It

is a non-routine activity which requires visualization

of images, understanding and interpreting

information contained in images and text, further

elaboration of given images, making valid

assumptions and reasoning (Duffy & O’Dwyer,

2015). Mobilizing and synchronizing these abilities is

a complex and time consuming process (Adeyemo,

2010; Wasis 2018) that goes beyond mere recalling,

understanding and applying (McBeath, 1992). In

problem-based MC questions the stem, which is

usually accompanied by a visual representation e.g. a

circuit, states the problem to be solved followed by

the key and a number of distractors. The student

solves the problem, finds the number-answer and then

makes the proper selection among the options given.

Problems demand mathematical computations and in

the case of problem-based MC tests miscalculations

can be disastrous. Assessment is done automatically

on the basis of the selection of the key answer, while

most of the student’s work is not communicated to the

assessor and therefore authentic effort is not

rewarded.

A particular type of problem-based MC format

was introduced in the course of “Electronics” during

the academic year 2019-2020. Each test consisted of

5 to 8 items which evaluated students’ competence in

problem solving (Bull & McKenna, 2004 p.39). The

stem described a problem in Electronics and it was

usually followed by the figure of a circuit. The

stem/problem addressed 1, 2 or 3 questions. Single

question items asked the student to choose the correct

answer between 4 options. Items addressing 2 or 3

questions were more demanding, since the questions

were inter-related. For each question 3 options were

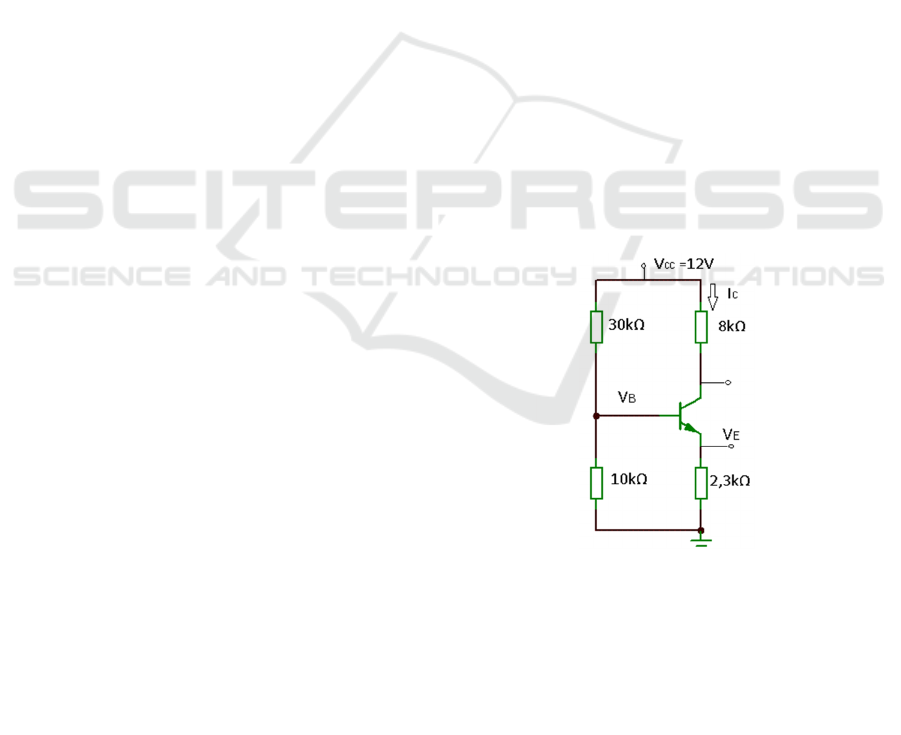

given. Fig.1 shows an example of an item addressing

two questions.

For the above circuit, choose the

correct pair of values of the

potential at the Base and the

Emitte

r

V

B

=2V

V

B

=3V

V

B

=4V

V

E

=2,3V

V

E

=2,7V

V

E

=3,3V

Figure 1: Example of a problem-based MC item.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

222

There was no negative marking (Holt, 2006), but

the students who answered correctly all the questions

of the individual item were given an extra bonus.

Answering by inspection was practically impossible

and the students had to solve the problem and then

select the correct answers. An average of 5 min was

allowed for each item, therefore a six item test lasted

for 30minutes. The test format left a rather limited

room for guessing especially if the student wanted to

get the extra bonus.

Problem-based MC tests taken during the delivery

of the course in “Electronics” allowed feedback for

students and tutors and helped students get

accustomed to the specific assessment format prior to

the final examination. The grades of the MC tests

contributed by 40% to the final grade of each student.

Participation in the continuous assessment scheme

was optional. Automated marking ensured

timesaving, but the time invested before the

examination increased considerably (Bull &

McKenna, 2004). Computer assisted assessment

provides the potential of administrative timesaving by

automatically entering marks into student record

system but this possibility requires an appropriate

interface between the assessment and the student

record system, which is not always available and thus

the potential of administrative efficiency is not

always realized (Bull, 1999).

Getting no marks because of miscalculations and

depending heavily on the number-answer may

generate feelings of unfairness, increased stress or

perceived difficulty. The question of how the students

evaluate the situation when they do not construct their

own solution, and just select a number-answer was of

particular interest in the research conducted.

4 COLLECTION OF DATA

The data were collected by means of an anonymous

questionnaire administered to the students via the

Open eClass platform, which is an Integrated Course

Management System offered by the Greek University

Network (GUNET) to support asynchronous e-

learning services. The respondents were full time

students of the Department of Electrical and

Electronic Engineering, University of West Attica.

The questionnaire was administered to 163 students

who followed the course in “Electronics” during the

academic year 2019-2020. Most of these students had

already taken 6 MC tests during the delivery of the

course (February 2020-June 2020). The tests were

held as distance ones before the COVID crisis as well

as after the university closure in March 2020.

The July and September (resit) 2020

examinations in “Electronics” were of the same

format and they were held as distance ones. The

students, who were familiar with the usage of the

platform, were asked to complete the questionnaire.

A total number of 112 students responded to the

questionnaire. Before the publication, a pilot study

was conducted to test its appropriateness.

The questionnaire collected information along

two dimensions: 1) How students compare MC to CR

exams in terms of anxiety, fairness and easiness, 2)

How students perceive some of the characteristics of

MC tests, namely: not asked to construct a solution,

choosing an answer, not having the opportunity to

express own view/solution to the problem and having

the opportunity to give the correct answer by

guessing. It also included demographic questions,

regarding gender, age, number of MC exams taken

and an additional item asking the students to report

whether they face any learning difficulties. The last

item included a “no answer” option.

A total of 105 valid answers were collected (17

women and 88 men). Eighteen (18) out of the 112

students who responded to the questionnaire self-

reported to face some type of learning difficulty

(15%), which is close to national-wide estimations

(Mitsiou, 2004). For Greek students in the secondary

education, the prevalence of dyslexia has been

estimated at 5.5%, which is a number consistent with

the data from other countries (Vlachos et al., 2013).

The responses retrieved were those from students

who had taken at least 4 MC examinations. The

students were asked to evaluate the two examination

formats along 10 questions replying on a 3-point

scale. The questionnaire included one open-ended

question: “Describe the positive or negative aspects

of MC as compared to CR exams. Feel free to make

any comments you like”.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Preference, Easiness, Anxiety and

Fairness

Preference: Among all the respondents a total number

of Ν=105 students, (53%) expressed a preference for

MC exams, 32% for CR exams, another 10% chose

“any of the two” and 4 students did not answer this

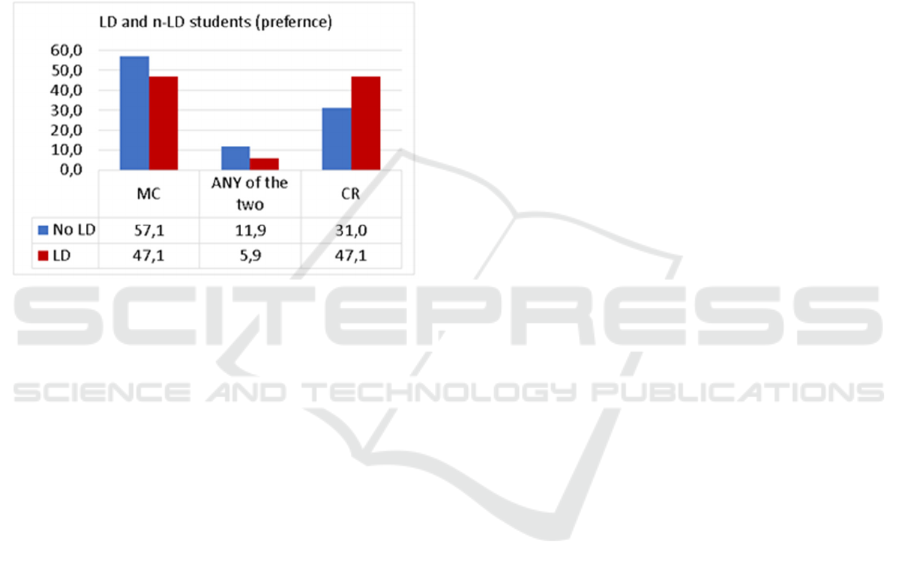

question. Figure 2 shows the preferences for the

students who self-reported to face some learning

difficulty (LD) and those who didn’t (n-LD). MC

tests are more popular among the students who do not

face learning difficulties (57%), while the students

Preference for Multiple Choice and Constructed Response Exams for Engineering Students with and without Learning Difficulties

223

with learning difficulties expressed an equal

preference for the two assessment formats (47%).

According to several publications, students prefer

MC over CR exams (Kaipa 2020; Gupta et al. 2016;

van de Watering, 2008; Tozoglu et al. 2004; Traub &

MacRury, 1990; Birenbaum & Feldman, 1998,

Zeidner 1987). Although preference for MC exams

has been associated with perceived fairness, easiness

and lower exam invoked anxiety, Traub and McRury

(1990) have attributed this preference to students’

belief that MC exam are easier to take and prepare for,

and thus they tend to consider that they will get higher

and presumably easier scores.

Figure 2: Preferences of students with and without LDs.

Easiness: Among the total number of the

respondents (N=105) 25% considered MC exams to

be easier compared to CR exams, 16% considered the

opposite and 59% reported that MC exams are as easy

as CR exams. For the students facing LDs a

percentage equal to 41% found MC exams to be

easier, while 35% of them considered the opposite.

The majority (67%) of the students with no LDs

expressed the view that MC exams are of the same

difficulty as CR exams.

Fairness: The majority (56%) of the respondents

expressed the view that MC exams are equally fair to

CR exams. Only 9% of them replied that MC exams

are fairer, while a percentage equal to 35% considered

MC exams to be less fair compared to CR exams. For

the students with LDs a percentage equal to 47%

replied that MC exams are less fair than CR exams

and another 24% of them held the opposite view. 79%

of students who expressed a preference for CR exams

consider MC exams to be less fair, while the vast

majority (~83%) of the students who expressed a

preference for MC exams consider them to be as fair

as CR exams. Therefore, fairness is not a strong

reason for the expressed preference for MC exams.

Anxiety: Only 30% of the respondents considered

MC exams to be less anxiety invoking compared to

CR exams, 22% expressed the opposite and another

49% of the respondents replied equal level of anxiety

for both examination formats. For the students with

LDs a percentage equal to 44% replied that MC

exams are more anxiety invoking compared to CR

exams and a percentage equal to 28% expressed the

opposite view.

5.2 Selecting and Not Constructing the

Answer

Five questions asked the students to express their

views on the issues of control, expression of own

ideas and feelings of empowerment or

disempowerment. One interesting feature of the

responses of the students is the polarity between the

views of the students depending on their preference

on the exam format.

Control: The majority of the students did not

perceive as a problem not having control over the

answer they submit. The percentage in the total

sample was equal to 57%, it dropped to 44% for the

students with LDs and it further dropped to 27% for

the students with a preference for CR exams.

Constructing own solution: The majority of the

students did not consider as a problem the fact that

with MC exams they were asked to select and not to

construct an answer. In the total sample this

percentage was equal to 54% and it dropped to 50%

for the students who reported LDs and it further

dropped to 15% for the group of students with a

preference for CR exams. On the contrary, among the

students who reported no LDs and a preference for

MC exams this percentage was as high as 81%.

Choosing between a number of given options:

Our findings indicate that this feature of the MC

exams is one of the most attractive to the students. A

percentage equal to 64% of the total sample liked the

fact that with MC exams they can choose between a

number of given options. For the students facing LDs

this percentage increased to 67%, while for the

students with no-LDs and a preference for MC exams

it was as high as 83%.

Relying on guessing: A percentage equal to 43%

of the total sample reported to be less worried with

MC exams because with some knowledge and a of bit

luck they will manage to pass the exams. For the

students with LDs this percentage was 39%, while the

students with no-LDs and a preference for MC exams

it was as high as 67%.

Making own learning demonstrable: A

percentage equal to 48% of the total sample expressed

the view that MC exams make them feel powerless

because they cannot show what they have learned.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

224

This percentage dropped to 44% for the students

facing LDs and it derived its lowest value (23%)

among the students who reported no-LDs and a

preference for MC exams.

5.3 Qualitative Data

An overall percentage equal to 52% of the

respondents provided answers to the free text

question. For the students with LD this percentage

was equal to 78%, for the no-LD students and a

preference for CR exams, this percentage was 81%

and it dropped to 42% for the students with no LD and

a preference for MC tests.

5.3.1 Students with LDs

The students with learning difficulties showed an

equal preference for MC and CR exams and one of

them declared no preference. We received 7 text

answers out of 8 students who self-reported to face

learning difficulties and a preference for MC tests.

The longer of these texts exhibited the problems

usually encountered by students with learning

difficulties, i.e. lack of clarity and problems with the

organization of ideas. In their answers the students

explained their preference for MC exams but they

also made clear that they are struggling with this

exam format as well. “MC tests is the best method for

me. With CR exams, I lose marks because I cannot

put in writing what I have in my mind. I need an

examination format that will give me the opportunity

to explain what I want to say”. “With MC exams I can

give an exact answer, text exams make me anxious

because I cannot put in writing things I do know”.

“With text exams I’m treated unfairly, because my

text answers do not make sense”. Table 1 displays the

issues raised by the students with LD and the

respective frequencies.

Table 1: Issues raised by the students with LDs in the free

text question.

Learnin

g

Difficulties

Preference

MC (8) CR (8)

Incoherent writing 4 1

Time mana

g

ement 3 2

Difficulty to comprehend

the stem and the options

1 3

Difficulties with MCs 3 -

Anxiet

y

3 0

Random answers 2 0

The problem of incoherent writing was the issue

with the highest frequency among the students who

preferred MC exams. Nonetheless, it must be noticed

that 3 of these students said that they face difficulties

with MC exams as well, but at least they don’t have

the problem of incoherent writing. Increased anxiety

and poor time management during exams

irrespectively of the examination format appears to be

another serious problem. Two of the students reported

difficulties in understanding the difference between

the options given and in some cases difficulties with

understanding the question itself. In such cases they

reported to make random choices.

Students with LD and a preference for CR exams

explained that their preference was based on their

difficulty to understand the meaning of the

question/stem or to tell the difference between the

various options. Time management was another issue

raised in two out of 6 quotes received from these

students. Three of the students who expressed a

preference for CR exams characterised MC exams as

“good”, “easier” and “helpful”, meaning that with

proper interventions, MC exams may become the

preferred option for these students as well.

People with LDs such as dyslexia, experience

educational and professional difficulties. During their

studies they struggle with writing and reading and in

some cases life satisfaction and sense of happiness

decrease as well (Kalka & Lackiewicz, 2018).

Students’ quotes are in agreement with previous

publications, which report that students with LD, in

some cases, are characterised by weak skills which

are relevant to MC exams. For example they may

have difficulties with information processing and

holding in short-term memory pieces of information

for active comparisons (Trammell, 2011). Poorly

designed MC questions have a negative impact on LD

students’ ability to select the correct answer. The

findings of the free text question indicate that MC

exams designed for students with LDs must contain

less questions, less options per question and extra

time must be given (Trammell, 2011). McKendree &

Snowling (2011) reported that for mixed assessment

type examinations, they found no indication of

disadvantage for students with dyslexia. It appears

that examinations of mixed format including MC, CR

and oral examination, are more suitable for students

with LDs

5.3.2 Students with LDs

The free text question was answered by 74 out of the

87 respondents who do not face learning difficulties.

The issues raised are shown in Table 2

, together with the respective frequencies for the 48

respondents who expressed a preference for MC

Preference for Multiple Choice and Constructed Response Exams for Engineering Students with and without Learning Difficulties

225

exams and the 26 students who expressed a

preference for CR exams. These issues were different

compared to those raised by the students with LDs.

More specifically they were related to: the time

available to complete the examination (15/74), the

shorter time required to complete MC exams (3/74),

the nature of assessment in engineering courses

(5/74), using the given options to check if the solution

of the problem is correct (12/74), negative marking

(4/74) and guessing in relation to the duration of the

exams (5/74).

The issue mentioned most frequently was the

duration of the exams. The students complained that

the time given to complete their answers was too

short. Looking at the literature one can see that an

average of 1-1.5minutes is recommended. Although

this time framework is considered adequate for MC

questions answered by inspection, it is not enough for

application type problem-based MC exams. Indeed,

in some MC tests it was seen that students with a good

overall performance, selected a wrong option in the

last one or two items they answered, indicating that

probably these choices were made at random.

Whenever there were adequate indications for short

duration of the exams, the marks were adjusted to

make sure that the students were not treated unfairly.

It appears that for application type problem-based

MC questions the average time per item needed varies

between 5 and 15 minutes depending on the

complexity of the question. This issue was raised

independently by 5 students who explained that

whenever the time available was limited they made

random choices.

Table 2: Issues raised by the students with no-LDs in the

free text question.

No learnin

g

difficulties

Preference fo

r

MC

(

48

)

CR

(

26

)

Not enough time 9 6

MCQ exams are shorte

r

1 2

Combined format 2 4

With MCQs you can

confirm results

7 5

Negative marking 3 1

Solution is more

important than answe

r

0 5

Forced to guess 2 3

Three students considered as a merit of the MC

format the shorter duration of the examination. A two

hours examination is tiresome given that in some

cases students may have to take two exams in one

day. Twelve students mentioned that with MC exams

they can compare the results of their solutions to the

options given in the MC question and get an idea of

whether their solution is correct. Some of the students

who preferred CR exams, considered that MC format

is not suitable for examining STEM courses. Their

argument assumed that in STEM courses solution

itself, not the number-answer, is what matters.

The students considered negative marking as

unfair for a number of reasons: First, it increases

anxiety, second the elimination of a distractor is time-

consuming in itself and third, negative marking

reduces the marks the student got answering correctly

questions which assess another topic. As the students

said: “There is no logic in negative marking because

both of them (to find the correct answer and eliminate

a distractor) take the same time”. “Negative marking

makes me anxious because a wrong answer will

reduce the marks from the correct answers I gave”. “I

understand why negative marking has been

introduced, but is it really necessary?”, “I don’t like

negative marking especially when there are many

options per item, it takes a lot of time to evaluate each

one of them”.

The students considered a mix of the two formats

as preferable. This issue was raised by 6 students as a

proposal to the problem of balancing between MC

exams and their need to show what they have leaned.

As one student said “I would like to have the

opportunity to explain my choices but necessarily in

all the questions”

6 DISCUSSION

The findings of this exploratory research give a snap-

shot of the attitudes and perceptions of the

participants on the two examination formats.

Students’ preferences are mediated by the level of

studies, subject examined, educational and cultural

settings (Zeidner, 1987; Tozoglu 2004; Gatfield &

Larmar, 2006). It is quite probable that the students

would have reported different preference percentages

or different levels of perceived anxiety, easiness and

fairness had they been asked to answer MC questions

in Electronics but not involving the solution of

problems. It is also assumed that the sudden change

from in-class to distance examination and university

closure due to COVID-19 pandemic, have affected

students’ replies.

Level of test anxiety has been related to the

preference towards the two examination formats:

Students experiencing high exam anxiety tend to

prefer the MC format, while those characterized by

lower test anxiety tend to prefer essay exams

(Birenbaum & Feldman, 1998). Overall, students

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

226

prefer exam formats which reduce anxiety (van de

Watering et al. 2008). Zeidner (1987) reported that in

his survey, 80% of the respondents judged MC exams

to be easier, 56% to be more fair and 83% to invoke

less anxiety. In a similar study Tozoglu et al. (2004)

reported that 64% of the participants considered MC

exams to be fair or very fair and only 28% of them

viewed them as anxiety invoking. In the present

study, it is seen that although the majority of the

respondents (55%) expressed a preference for MC

exams only a relatively small percentage of them

consider MC exams to be easier (25%), fairer (9%)

and less stressful (30%). Although in the findings of

previous studies (Tozoglu, 2004; Zeidner 1987) MC

exam preference appears to co-occur with high

perceived easiness, fairness and less invoked anxiety,

the findings of this study indicate that students may

prefer MC exam although they do not consider this

examination format as invoking less stress, being

fairer or easier compared to CR exams (Table 3).

Table 3: Quantitative results by category.

MC exams are LD

(

%

)

no-LD

(

%

)

Total

(

%

)

Easie

r

41 21 25

Faire

r

24 6 9

Less anxiet

y

28 30 30

Table 3 presents the percentage of the students

who consider MC exams to be easier, fairer and less

stress invoking compared to CR exams.

The low levels of perceived easiness, fairness and

reduced anxiety for MC format, recorded in this study

are possibly related to the following three factors:

First, the data were collected during a period of strict

social distancing measures due to COVID-19

pandemic (September 2020) when students were

coping with distance examinations after a 3 months

period of obligatory distance teaching. When

assessment moves from face-to-face to distance, it

becomes very difficult to ensure that students are not

cheating (Rapanta et al. 2020). Some universities use

available software to detect cheating and plagiarism

during exams or assignment submission, while

examination redesign has been proposed as an

alternative option to minimize cheating (Munoz,

Mackay, 2019). MC exams, beside other reasons, are

used to prevent cheating. Version exams where each

student answers a number of equivalent MC questions

selected randomly from a bank of questions, gives

rise to questions of fairness (Emeka & Zilles, 2020).

Alternatively, the participants of this study received

the same questions in a random order. This promotes

external fairness (Leach, Neutze & Zepke, 2001) and

makes cheating less probable. Setting stricter time

limits for the duration of the examinations was

another measure suggested to prevent possible

dishonest behaviours (OECD, 2020, p.3,5). Giving to

the students a fixed amount of time to answer each

question can preclude students from finding the

answer from other sources or sharing their answers

with colleagues (Ladyshewsky. 2015; Schultz et al.

2008). On the other hand, if the students feel that the

time given to answer the exam questions is not

enough may generate feelings of frustration, reduced

fairness and increased anxiety. Increased stress, short

duration and difficulty of exam questions are factors

contributing to the negative experiences of the

students related to distance examinations during the

COVID-19 period (Elsalem et al. 2020; Clark et al.,

2020).

Second, problem solving in Physics and

Engineering is difficult. Presumably the students

would have reported lower anxiety and higher

easiness had they been asked to answer MC questions

in Electronics not involving the solution of problems.

For some students the solution of a problem takes

longer compared to other students (Redish et al.,

2006) and this may affect the perceived level of

difficulty. Although the marks were adjusted to make

sure that no student was disadvantaged because of the

duration of the MC examination, the students did not

enjoy the alleged easiness and reduced levels of stress

which characterise MC exams.

Third, the specific type of problem-based MC

exams left little room for guessing. One of the

questions asked the students to rate the possibility of

guessing. A percentage equal to 42% of the

respondents considered that they would manage to

pass the exams based on some knowledge and

guessing while 42% disagreed. The respective

percentage in Kaipa’s (2020) publication was 77%. If

students’ preference for MC exams is influenced by

the belief that with MC exams it is easier to achieve

high scores (Traub & McRury 1990), low

expectations for guessing may affect perceptions of

easiness and anxiety.

Various publications have associated high

preference for MC exams with high levels of

perceived easiness, fairness or reduced anxiety

(Zeidner, 1987; Birenbaum & Feldman, 1998;

Tozoglu et al., 2004; Kaipa, 2020). Traub & McRury

(1990) reported that students may prefer MC exams

because they think they are easier to take and achieve

higher scores. The findings of the present study show

that fairness, easiness and reduced anxiety are not

necessary conditions for preferring MC exams. It

appears that “choosing between a number of given

options” is the characteristic that loaded considerably

Preference for Multiple Choice and Constructed Response Exams for Engineering Students with and without Learning Difficulties

227

to the expressed preference for MC exams (64%).

One cannot exclude the possibility that the students

expressed a preference for MC exams based on

reasons not included in this questionnaire or their

preference was based on feelings of convenience i.e.

instead of providing a detailed solution they just had

to make some calculations, without stating

assumptions or making explanations and then select

an option. Birenbaum & Feldman (1998) found that

students with a deep learning approach tend to prefer

CR exams while students characterized as surface

learners prefer MC format.

The data collected in this study identified two

profiles among the students who reported no-LDs

corresponding to the preference for each examination

format: The first profile includes the students with no

LDs and a preference for MC exams. These students

do not perceive as a problem the fact that with MC

exams they do not construct a solution (81%), or they

do not control the answer the give (85%), they do not

feel powerless if they are not given the opportunity to

show what they have learned (69%) and they like the

fact that with MC exams they can choose the answer

between a number of given options (85%). The

second profile, includes the students with no-LDs and

a preference for CR exams. These students perceive

as a problem the fact that with MC exams they are not

asked to construct a solution (69%), they do not

control the answer they give (69%), they feel

powerless because they are not given the opportunity

to show what they have learned (92%) and they don’t

like the fact that with the MC exams they have to

select between a number of given options (58%).

It appears that the students interviewed by Paxton

(2000) expressed views similar to those of the

students who prefer CR exams in this study. Contrary

to the findings of Paxton, the participants of this study

showed a low interest in submitting original solutions

and they didn’t mind being choosers instead of

solution creators. Only a percentage equal to 48% of

the total sample expressed the view that MC exams

make them feel powerless because they cannot show

what they have learned. Discourse on student

empowerment includes learners themselves and puts

into perspective their willingness to get involved in

decisions about teaching and assessment (Leach et al.,

2001). In a more realistic approach, Holley & Oliver

(2000) have broadened the scope of the power

relations’ discussion to include management. More

importantly, power relations in universities are not

exhausted in the teacher-student relations and are not

instantiated during exams only. Texts, policies and

discourses intervene in the power relations by making

certain views official while silencing or omitting

others. As Luke points out this is a political selection

that involves the valorisation of particular discourses,

subjectivities and practices (Luke, 1995-1996, p. 36).

In the “marketized” university literature, MC

exams is seen as the suitable assessment form to

enable students get good grades in return of high

student satisfaction scores in Student Satisfaction

Surveys. In this way, the university records properly

high levels of student achievement and high

student/customer satisfaction (Watts, 2017), which

enhance the university’s attractiveness in the market

and adds credibility to management’s voice. The shift

in authority from the professors to the managers has

given rise to novel characteristics in contemporary

universities. For example, a survey published in The

Guardian (2015) found that “46% of academics said

they have been pressurised to mark students’ work

generously”. MC exams are not to blame for being

easy or too easy. Problem-based MC exams, for

example, are not perceived as too easy. According to

our findings the majority of the students consider

them as being equally easy (59%), equally fair (57%)

and invoking equal (49%) or less anxiety (30%)

compared to CR exams. Therefore, easiness is not a

generic characteristic of MC exams. Nonetheless,

even in cases when MC exams are not perceived as

easy, the students still expressed a preference for

them. The strongest reasons explaining this

preference are: the opportunity to pass the exams by

making the correct choices instead of constructing a

solution (64%) and guessing (43%).

7 CONCLUSIONS

Problem-based MC exams is an objective type of

examination suitable for engineering education.

Students with learning difficulties showed an equal

preference for MC and CR examination formats.

From the replies given to the free-text questions it

became clear that difficulties persist for both

examination formats. Following Leach et al., (2001)

it is concluded that students with LDs could have a

role in an assessment partnership. The students with

LDs are only a small percentage of the students and

their difficulties affect not only exam results but also

studying. Choosing a suitable examination format

would make studying and preparation for the exams a

more meaningful effort, while assessment would play

a motivating role within and not outside the learning

process.

The findings of the present study show that overall

the participants prefer MC exams (55%) compared to

CR ones. This percentage is much lower compared to

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

228

those reported in previous studies e.g. 83% by

Zeidner (1987) and 65,5% by Kaipa (2020). The

students perceive MC exams to be more or less

equally fair, easy and anxiety invoking compare to

CR exams. Choosing, instead of constructing the

answer, was particularly popular among the

respondents.

The students were also asked to express their view

on the fact that with MC exams a great part of their

work is not communicated to the assessor. The replies

received were differentiated according to the

preference towards the two examination formats.

Students with a preference for MC exams liked the

fact that they had just to choose an answer, they were

not interested to show what they have learned or

construct their own solutions to the problems stated

in the MC exam questions. On the contrary, students

with a preference for CR exams perceive as a problem

the fact that with MC exams they are not asked to

construct a solution and they do not control their

answer, they feel powerless because they are not

given the opportunity to show what they have learned

and they don’t like the fact that with the MC exams

they are asked to select between a number of given

options.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

One of the authors is grateful to Cimon Anastasiadis

for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

Adeyemo, S. A. (2010). “Students’ ability level and their

competence in problem-solving task in physics”,

International Journal of Educational Research and

Technology, 1(2), pp. 35 – 47.

Biggs, J.B., Kember, D., & Leung, D.Y.P. (2001) “The

Revised Two Factor Study Process Questionnaire: R-

SPQ-2F”, British Journal of Educational Psychology,

71, pp. 133-149

Birenbaum, M., & Feldman, R. A. (1998). Relationships

between learning patterns and attitudes towards two

assessment formats. Educational Research, 40(1), 90–

97.

Bridgeman, B. (1992) “A comparison of quantitative

questions in open-ended and multiple-choice formats”,

Journal of Educational Measurement, 29, pp. 253–271.

Bull, J. (1999). Computer-Assisted Assessment: Impact on

Higher Education Institutions. Journal of Educational

Technology & Society, 2(3), 123-126

https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.2.3.123

Bull, J. & McKenna, C., (2004) Blueprint for computer-

assisted assessment, London, Routledge Falmer pp.7-9

Bush, M. (2001), “A multiple choice test that rewards

partial knowledge”, Journal of Further and Higher

Education, 25(2), pp. 157–163.

Chan N., & Kennedy P. E., (2002) “Are Multiple-Choice

Exams Easier for Economics Students? A Comparison

of Multiple-Choice and "Equivalent" Constructed-

Response Exam Questions”, Southern Economic

Journal, 68(4), pp. 957-971

Clark T.M., Callam, C. S., Paul N. M., Stoltzfus M. W., and

Turner D., (2020) “Testing in the Time of COVID-19:

A Sudden Transition to Unproctored Online Exams”,

Journal of Chemical Education 97(9), pp. 3413–3417

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00546

Duncan H. & Purcell C., (2020) “Consensus or

contradiction? A review of the current research into the

impact of granting extra time in exams to students with

specific learning difficulties (SpLD)”, Journal of

Further and Higher Education, 44:4, pp. 439-453, DOI:

10.1080/0309877X.2019.1578341

Duffy G., Sorby S., Bowe B., (2020) “An investigation of

the role of spatial ability in representing and solving

word problems among engineering students”, J Eng

Educ 109, pp. 424-442,

https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20349

Elsalem L. Al-Azzam N., Jum'ah A. A., Obeidat N.,

Sindiani A. M., Kheirallah K. A., (2020) “Stress and

behavioral changes with remote E-exams during the

Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study among

undergraduates of medical sciences” Annals of

Medicine and Surgery 60, pp. 271-279

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2020.10.058

Emeka Ch., Zilles C., (2020) “Student Perceptions of

Fairness and Security in a Versioned Programming

Exam”, ICER '20: Proceedings of the 2020 ACM

Conference on International Computing Education

Research, pp. 25–35

https://doi.org/10.1145/3372782.3406275

Entwistle, A., & Entwistle, N. (1992), “Experiences of

understanding in revising for degree examinations”,

Learning and Instruction, 2, pp. 1– 22

https://doi.org/10.1016/0959-4752(92)90002-4

Gatfield, T., & Larmar, S. A. (2006), “Multiple choice

testing methods: Is it a biased method of testing for

Asian international students?”, International Journal of

Learning, 13(1), pp. 103-111.

Gipps C V (2005), “ What is the role for ICT‐based

assessment in universities? ” , Studies in Higher

Education, 30(2), pp. 171-180, DOI:

10.1080/03075070500043176

Graves W. H., (2004), “Academic Redesign: Accomplish

more with less”, JALN 8(1), pp. 26-38

Gregg, N., & Nelson, J. M., (2012) “Meta-Analysis on the

effectiveness of extra time as a test accommodation for

traditional adolescence with learning disabilities: More

questions than answers.” Journal of Learning

Disabilities 45(2) pp.128-18 doi:

10.1177/0022219409355484

Preference for Multiple Choice and Constructed Response Exams for Engineering Students with and without Learning Difficulties

229

Gupta Chandni G., Jain A., D’Souza A. S., (2016) “Essay

versus multiple-Choice: A perspective from the

undergraduate student point of view with its

implications for examination”, Gazi Medical Journal,

27, pp. 8-10 DOI:10.12996/GMJ.2016.03

Holley, D and Oliver, M. (2000) “Pedagogy and new power

relationships”, The International Journal of

Management Education, available at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238721033_

Pedagogy_and_New_Power_Relationships/citations

Holt A., (2006) “An Analysis of Negative Marking in

Multiple-Choice Assessment” 19th Annual Conference

of the National Advisory Committee on Computing

Qualifications (NACCQ 2006), Wellington, New

Zealand. Samuel Mann and Noel Bridgeman (Eds), pp.

115-118, available at https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/

viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.679.2244&rep=rep1&t

ype=pdf

Kaipa R. M., (2020) “Multiple choice questions and essay

questions in curriculum”, Journal of Applied Research

in Higher Education, ISSN: 2050-7003

DOI:10.1108/jarhe-01-2020-0011

Kalka D. & Lockiewicz M., (2018), “Happiness, life

satisfaction, resiliency and social support in students

with dyslexia”, International Journal of Disability,

Development and Education 65(5), pp.493-508

https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2017.1411582

Ladyshewsky, RK 2015, “Post-graduate student

performance in supervised in-class vs. unsupervised

online multiple choice tests: implications for cheating

and test security”, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher

Education, 40 (7), pp. 883-897

Leach L., Neutze G., & Zepke N., (2001) “Assessment and

Empowerment: Some critical questions”, Assessment

& Evaluation in Higher Education, 26:4, pp. 293-305,

DOI: 10.1080/02602930120063457

Luke, A. (1995–1996) “Text and discourse in education: an

introduction to critical discourse analysis”, in: M.

Apple, (ed.) Review of Research in Education

(Washington DC, American Educational Research

Association)

Lukhele, R., Thissen, D., & Wainer, H. (1994), “On the

relative value of multiple-choice, constructed response,

and examinee selected items on two achievement tests”,

Journal of Educational Measurement, 31(3), pp. 234–

250.

McBeath, R.J. (Ed.) (1992) Instructing and Evaluating in

Higher Education: A Guidebook for Planning Learning

Outcomes, Englewood Cliffs: Educational Technology

Publications.

Martinez, M. E. (1999), “Cognition and the question of test

item format”, Educational Psychologist, 34(4), pp.

207–218.

McKendree J & Snowling M J (2011), “Examination results

of medical students with dyslexia”, Medical Education,

45, pp. 176-182

Mitsiou G. (2004), http://www.fa3.gr/eidiki_agogi/1-math-

dysk.htm Accessed 12 September 2020

Munoz, A., & Mackay, J. (2019), “An online testing design

choice typology towards cheating threat minimisation”,

Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice,

16(3) Article 5 https://ro.uow.edu.au/jutlp/vol16/iss3/5.

Accessed 15 June 2020.

Núñez-Peña M. I., & Bono R., (2020) “Math anxiety and

perfectionistic concerns in multiple-choice

assessment”, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher

Education, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2020.1836120

OECD (2020), “Remote online exams in higher education

during the COVID-19 crisis”, available from:

oecd.org/education/remote-online-exams-in-higher-

education-during-the-covid-19-crisis-f53e2177-en.htm

Pamphlett, R. and Farnill, D. (1995), “Effect of anxiety on

performance in multiple choice examination”, Medical

Education, 29 pp. 297-302.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.1995.tb02852.x

Parmenter D.A., (2009) “Essay versus Multiple-Choice:

Student preferences and the underlying rationale with

implications for test construction”, Academy of

Educational Leadership, 13 (2), pp.57-71

Paxton, M., 2000 “A linguistic perspective of multiple

choice questioning,” Assessment and Evaluation in

Higher Education, vol. 25(2), pp. 109-119

https://doi.org/10.1080/713611429

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guardia L., Koole

M., (2020) “Online University Teaching During and

After the Covid-19 Crisis: Refocusing Teacher

Presence and Learning Activity”, Postdigital Science

and Education 2, pp. 923–945

https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00155-y

Redish E. F. Scherr R. E. and Tuminaro J., (2006) “Reverse

Engineering the solution of a “simple” Physics

problem: Why learning Physics is harder than it looks”,

The Physics Teacher, 44, pp. 293-300,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.2195401

Scharf, E. M., & Baldwin, L. P. (2007), “Assessing multiple

choice question (MCQ) tests - a mathematical

perspective”, Active Learning in Higher Education,

8(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1469787407074009

Schultz, M, Schultz, J & Round, G (2008), “Online non-

proctored testing and its affect on final course grades”,

Business Review, Cambridge, 9, no. pp. 11-16

Scouller, K. (1998), “The influence of assessment method

on students' learning approaches: Multiple choice

question examination versus assignment essay”, Higher

Education 35, pp. 453–472

https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003196224280

Simkin, M.G. and Kuechler, W.L. (2005), “Multiple‐

Choice Tests and Student Understanding: What Is the

Connection? ” Decision Sciences Journal of

Innovative Education, 3 pp. 73-98.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4609.2005.00053.x

Tan, Kelvin H. K., (2012), "How Teachers Understand and

Use Power in Alternative Assessment", Education

Research International, 2012, Article ID 382465, 11

pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/382465

Tozoglu, D, Tozoglu, MD, Gurses, A, Dogar, C., (2004)

“The students’ perceptions: Essay versus multiple-

choice type exams”, Journal of Baltic Science

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

230

Education 2(6) pp. 52-59

http://oaji.net/articles/2016/987-1482420585.pdf

Trammell J., (2011), “Accommodations for Multiple

Choice Tests”, Journal of Postsecondary Education and

Disability, 24(3) pp. 251-254

Traub, R. E., & MacRury, K. (1990), Multiple choice vs.

free response in the testing of scholastic achievement,

in K. Ingenkamp & R. S. Jager (Eds.), Tests und Trends

8: Jahrbuch der Pa ̈dagogischen Diagnostik (pp. 128–

159). Weinheim und Basel: Beltz.

Triantis, D., Ventouras, E., Leraki, I., Stergiopoulos, C.,

Stavrakas, I., Hloupis, G., (2014), “Comparing

Electronic Examination Methods for Assessing

Engineering Students - The Case of Multiple-Choice

Questions and Constructed Response Questions”,

Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on

Computer Supported Education 1, pp.126-132.

UNIWA, (2020) https://www.uniwa.gr/

van de Watering, G., Gijbels, D., Dochy, F., van der Rijt J.,

(2008) “Students’ assessment preferences, perceptions

of assessment and their relationships to study results”

Higher Education 56, pp. 645-658

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-008-9116-6

Ventouras Ε., Triantis, D. Tsiakas, P. Stergiopoulos, C.,

(2011), “Comparison of oral examination and

electronic examination using paired multiple-choice

questions”, Computers & Education, 56(3) pp. 616-624

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.10.003

Ventouras E., Triantis D., Tsiakas P., Stergiopoulos C.,

(2010), “Comparison of examination methods based on

multiple-choice questions and constructed-response

questions using personal computers” 54(2), pp. 455-

461 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.08.028

Vlachos, F., Avramidis E., Dedousis G., Chalmpe M.,

Ntalla I., Giannakopoulou M. (2013) "Prevalence and

Gender Ratio of Dyslexia in Greek Adolescents and Its

Association with Parental History and Brain Injury."

American Journal of Educational Research 1.1 pp. 22-

25 DOI: 10.12691/education-1-1-5

Wasis, Kumaidi, Bastari, Mundilarto, Atik Wintarti , (2018)

“Analytical Weighting Scoring for Physics Multiple

Correct Items to Improve the Accuracy of Students’

Ability Assessment”, Eurasian Journal of Educational

Research 76 pp. 187-202, DOI:

10.14689/ejer.2018.76.10

Watts R., (2017), “Public Universities, Managerialism and

the Value of Higher Education”, London: Palgrave

Macmillan

Zeidner M., (1987) “Essay versus Multiple-Choice Type

Classroom Exams: The Student’s Perspective”, The

Journal of Educational Research, 80(6), pp. 352-358

DOI: 10.1080/00220671.1987.10885782

Preference for Multiple Choice and Constructed Response Exams for Engineering Students with and without Learning Difficulties

231