Role of Citizens in the Development of Smart Cities: Benefit

of Citizen’s Feedback for Improving Quality of Service

Priyanka Singh

1a

, Fiona Lynch

2b

and Markus Helfert

1c

1

School of Business, Innovation Value Institute, Lero, Maynooth University, Maynooth, Co. Kildare, Ireland

2

School of Science & Computing, Waterford Institute of Technology (WIT), Waterford, Ireland

Keywords: Smart City Framework, Citizens, Smart Service.

Abstract: The initiatives around the involvement of citizens in smart city development is increasing significantly with

the aim of enhancing the quality of life for the citizens of these cities through better public services. There is

plethora of studies discussing various technologies and platforms to obtain citizen’s feedback for smart city

development. Nonetheless, there are very limited studies which provide guidance on how to utilise those

feedbacks and improve quality of the services in order to provide better experience to the citizens. This paper

examines past work regarding different aspects of citizen’s involvement in smart cities and classify the

existing literature through the lens of a smart city framework. This study offers an overview of diverse

concepts and platforms associated with the role of citizens in smart city design and development by featuring

possible linkages to the related layers of the adopted framework. This study further proposes a conceptual

model to incorporate citizen’s feedback in more structured way at architecture level in order to meet their

requirements and to provide improved quality of services to them.

1 INTRODUCTION

A smart city needs to be implemented according to

the local constraints and opportunities, taking into

consideration the diverse culture, requirements, and

features of cities in different geographical areas and

countries (Dameri et al., 2019). Hollands, (2008)

states that if smart cities want to empower social,

environmental, economic, and cultural development,

then it should not only be based on the use of ICT.

There is an ignorance towards the non-technical

problems which include management, policies,

citizens and creating a void in the field (Habibzadeh

et al, 2019; Nam and Pardo, 2011). There is a need to

consider urban issues beyond technological

innovation (Yigitcanlar et al, 2019). The smart city

paradigm seems to have smoothly and generally

replaced that of the sustainable city over the decades

which is being modified by emerging claims of

citizen-centeredness (Lorquet & Pauwels, 2020). In

order to make citizen centred smart cities, many

initiatives have been taken and one of them is open

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6182-6111

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7558-5926

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6546-6408

innovation (ibid). However, such initiatives are

mostly used by public sector organisations to change

the way citizens behave instead of giving them more

influence in public sector processes (Pedersen, 2020).

Nakamura and Managi, (2020) argued that citizen

satisfaction is an important metric in evaluating city

performance as it would ultimately affect the benefit

and comfort to city inhabitants. Sustainable city

development should not only be based on objective

performance data and municipal service evaluations,

but also on people’s subjective city evaluation and

life satisfaction (ibid). Thus, the requirements of the

citizens should be considered as a critical component

for the development of the successful smart cities

(Heaton and Parlikad, 2019). However, these

requirements have often been ignored over the

technological and strategic development (ibid).

Additionally, although the rate of citizen participation

is low, but they often provide meaningful comments

that have the ability to inform the decision-making

process (ibid). Thus, for a smart sustainable city, a

sense of community should be incorporated in policy

Singh, P., Lynch, F. and Helfert, M.

Role of Citizens in the Development of Smart Cities: Benefit of Citizen’s Feedback for Improving Quality of Service.

DOI: 10.5220/0010442000350044

In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems (SMARTGREENS 2021), pages 35-44

ISBN: 978-989-758-512-8

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

35

making which consider citizen’s evaluation on smart

sustainable cities, public services and facilities

(Macke et al, 2019). Citizens' engagement is a

fundamental requisite for the accomplishment of a

sustainable and inclusive urban development (Corsini

et al, 2019). Thus, a socio-technical perspective is

required when organizations embark on smart

initiatives in order to address new challenges for

enterprises and service providers (Ekman, Röndell, &

Yang, 2019; Bednar and Welch, 2019). Moreover,

there is a requisite for more suitable tools and

protocols to assist greater public participation in the

viability stage before stable options are decided in the

smart city field (Corsini et al, 2019). Smart cities are

already extremely complex System of Systems (SoS),

and the emerging trend in urban planning is towards

adding smart systems into the urban environment

with the aim of improving the quality of life for the

citizens of the city (Clement et al, 2017).

Pourzolfaghar and Helfert, (2017), emphasise that

citizen’s requirements should be considered as a

client requirement in the design process of the

services. It has been further highlighted that the

maintenance phase is crucial in delivering qualified

and sustainable services to the citizens which has

been neglected in majority of the enterprise

architecture frameworks (Zachman, DoDAF, FEAF,

TEAF, and TOGAF) for smart cities (ibid). In order

to address the issue identified in those frameworks,

Pourzolfaghar et al., (2019) proposed the ‘Smart City

Enterprise Architecture Framework’ which

incorporated two new layers (context layer and

service layer). These new layers aimed to capture the

viewpoints of different stakeholders including

citizens. The aim of this study is also to understand

the role of citizens in smart city development and how

existing literature support their involvement.

Therefore, this study finds the proposed framework

suitable for analysing the existing literature from the

citizens’ viewpoint and to propose future research

agenda for the further investigation. Thus, this paper

aims to discuss citizen’s involvement in smart city

development, and provides new insights through the

lens of a ‘Smart City Enterprise Architecture

Framework’ proposed by Pourzolfaghar et al , (2019).

The detail of this framework is discussed in section 2.

The remaining sections of the paper are structured as

follows: Section 2 provides the detail of literature

review by examining the existing literature from the

lens of adapted smart city framework. Section 3

discusses the identified research gap. In Section 4, a

case study has been discussed and accordingly in Sec.

5 a conceptual model has been presented to direct the

further research in the future. Finally, Sect. 6

summarizes the contributions of the paper and future

work of the research.

2 ROLE OF CITIZEN FROM THE

LENS OF SMART CITY

FRAMEWORK

In this section various platforms and concepts

associated with the involvement of citizens in the

design and development of smart cities are considered

based upon smart city framework proposed by

Pourzolfaghar et al., (2019). The motivation for

selecting this framework is to understand existing

literature from different layer’s perspective which

support citizens through various platforms and

technology in the development of smart cities. This

framework would provide a holistic viewpoint by

positioning the research about citizen’s involvement

in different layers (Context, Application,

Technology, Service). The framework consists of

four layers. First layer is service layer which define

appropriate goals, scope, etc. for the services with

regard to the smart city requirements, concerns, and

priorities. Second layer is a context layer which

encapsulates the information regarding the strategies,

priorities, stakeholders and their concerns to deliver

effective services to the citizens. The third layer is

information layer identifying the data elements, the

data interrelations, and data flows required to support

service function (Minoli, 2008; Pourzolfaghar et al,

2019). The last layer is technology layer which

supports the information and application functions

from the information layer. The following sections

provide insight into the existing literature on the

involvement of citizens in the development of smart

cities from the lens of these layers.

2.1 Service Layer

This layer defines aim and scope for the services that

are related with smart city requirements, concerns,

and priorities (Pourzolfaghar et al., 2019). One of the

activities of this layer is to define an experience and

value proposition that the service is intending to

provide. For instance, providing the improved quality

of the services to the citizens (ibid). Therefore, in this

layer, the emphasis is on considering citizen’s

feedback to understand the smart city requirements,

concerns and priorities from their perspective (ibid).

E-participation in the form of providing service

feedback has positive impact on the performance of

service delivered (Allen et al, 2020). However, it

SMARTGREENS 2021 - 10th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

36

remains unconvincing whether new government-

citizen interface collaboration has achieved the

fundamental goal of improving service quality for

citizens (ibid). Soft assets such as organizational

capital, social capital, and information and

knowledge-related capital help to understand

citizen’s role in order to support building and

maintaining the key areas that reinforce Smart City

(SC) development (Wataya & Shaw, 2019). These are

further linked to the cycle of improving the quality of

services and also a prime source of innovative value

creation for SC development (Wataya & Shaw,

2019). Citizens can also use mobile Apps to report

damages and other issues with the city’s

infrastructure which can result in providing better

quality of services to the citizens (Abu-Tayeh,

Neumann & Stuermer, 2018). However, it is possible

that we have outstanding performance indicators for

the services but if citizens are not satisfied with the

delivered services, then it can disappoint them at the

end (Sofiyabadi, Kolahi, & Valmohammadi, 2016).

Therefore, once actions are implemented, monitoring

has to be carried out to determine if the actual impact

varies from the anticipated impact in the servcies

from the citizen’s perespective (Abella et al, 2019). A

rich collection of citizen’s behaviour data can be

helpful in further optimising the services (Solaimani,

Bouwman, & Itälä, 2015). E-government systems are

more likely to be re-used by the citizens if they

recognise that the experience with those new systems

are better than the traditional ones (Alruwaie et al,

2020). These system types should be evaluated

through citizens' prior experience based on their level

of expectations (ibid). However, at present there are

very limited studies which provide guidance on how

to evaluate such systems based on citizen’s quality of

experiences. Ballesteros et al (2015) defined Quality

of Experience (QoE) from the end user’s (citizens)

perspective as:

Usability: The usage of a product by identified users

to accomplish desired goals with effectiveness,

satisfaction and efficiency in a specified context.

Personalization: The capacity to deliver services as

per the individual’s need based on the analysis of their

behaviour and inclinations.

Usefulness: It is associated with the satisfaction or

needs of the users and how the functions or features

of the product being valued by the users that is

available to them.

Transparency: It should be convenient for everyone

to recognise what actions are being performed in

terms of the operation of the services.

Effectiveness: Users can finish the defined tasks in

order to achieve the objectives of the service or

product and they should be able to do what they want

to do.

These quality factors could be useful in

understanding the citizen’s requirements in a better

way which would result in improved QoS.

2.2 Context Layer

This layer captures the smart city context information

about strategies, priorities, stakeholders and their

concerns to deliver effective services to the citizens

(Pourzolfaghar et al., 2019). From this layer’s

perspective smart city initiatives focus on the

strategies, and priorities from the citizen’s viewpoint

(ibid). Linders et al, (2018), highlighted that there is

a requirement to flip the service delivery model by

shifting from the “pull” approach of traditional e-

government towards a “push” model. Through this

model government proactively and impeccably

delivers just-in-time services to citizens designed

around their specific needs, circumstance,

preferences, and location (ibid). Four governance

paradigms have been introduced i.e. bureaucratic,

consumerist, participatory and platform to categorize

the citizen- administration relationships (Janowski,

2018). These models facilitate a better understanding

of governance arrangements resulting from

visualization, simulation and analysis; which could

additionally lead to better sustainable development

(ibid). Nevertheless, an evolving problem is that there

is a lack of appropriate tools to support citizens in

many parts of co- design process (Wolff et al, 2020).

A set of design templates have been introduced to

enable citizens in converting their ideas into

technology applications which can be used during the

design process (ibid). These types of methods and

tools certainly assist in obtaining citizen’s ideas and

their inputs for designing the services. However, there

is a lack of understanding on how these ideas are to

be implemented in the actual design of services and if

those ideas really have any impact in improving the

quality of the services. Cellina et al., (2020), proposed

a framework where the key application functionalities

were co-designed with a group of interested citizens

which resulted in even more significant impacts in

terms of urban governance practices. Vidiasova &

Cronemberger, (2020) identified different levels of

understanding regarding how citizens identify the

smart city initiatives; Although many respondents

were direct and elaborated on many aspects of a smart

city, their understanding remains diffused and vague

despite high levels of engagement with traditional e-

government technologies (Vidiasova &

Cronemberger, 2020). Major public resources are

Role of Citizens in the Development of Smart Cities: Benefit of Citizen’s Feedback for Improving Quality of Service

37

invested in technical solutions, but the appropriate

means of assessing success (social value) is still

unclear or remain uncultivated in light of the

expectations of citizens (ibid). When it comes to

engagement, social media and online communication

have transformed the way citizens engage in all

aspects of lives from shopping and education, to how

communities are planned and urbanised, and

therefore governments need new ways to listen to its

citizens (Alizadeh et al, 2019). De Guimarães et al.,

(2020), identified multiple strategic drivers and can

help smart city rulers in the development of public

policies and to improve QoL, such as Transparency

(TRANS), Collaboration (CO), Participation and

Partnership (PP), Accountability (ACC), and

Communication (COM).

In order to obtain user value, the smart city

governance should work closely with citizens and

diverse stakeholders to identify the set of services by

prioritising citizen’s requirements for a long term city

transformation that can fast-track smart city

development (Kumar et al, 2019). However, current

standards, guidance and specifications have little

focus on the requirements of the citizens within a

Smart City framework (Heaton & Parlikad, 2019). To

address this issue, Heaton & Parlikad, (2019)

proposed a framework which offers a direct line-of-

sight from citizen requirements, the infrastructure

assets supporting used services, and the services used

within the city to meet that requirements, and then

validating if citizen requirements have been fulfilled.

Satisfaction surveys can be used as the product of

strategic planning (evaluation of the strategy success)

and secondly as the input to strategic planning

(problem issues should be dealt with in strategy)

which are vital for the public policy planning

(Kopackova, 2019). The rise of platform technologies

such as social media, IoT, and data analytics has the

potential to fundamentally change the role of

transparency in policy making (Brunswicker et al,

2019). It is further highlighted that citizens as

participants in policy making, move to the centre of

the discourse on transparency, and their opinions,

challenges, and responses to policies and policy-

related information come to be observable, sharable

and interpretable (ibid). In order to optimize citizen’s

participation outcomes, platform administrators

might consider either increasing private value

perceived by the citizen or public value where private

value has a greater effect on continuous e-

participation intentions than public value creation (Ju

et al, 2019). There is a requirement for cities to

involve non-traditional stakeholders in urban

planning processes such as social change initiatives,

citizen groups and informal sector representatives

(Schröder et al., 2019). Andreani et al., (2019)

presented a reference model in relation to citizen-

centred built environments, in the process of co-

creating the proposals by sharing a common design

path between public authorities, private citizens,

associations at different levels, and research centres,

and resulting in engaging the local community in

creating and providing feedback to the design

proposals (Andreani et al., 2019).

2.3 Information Layer

This layer identifies the data elements, data flows,

and the interrelations between data required to

support service function (Pourzolfaghar et al., 2019).

This layer plays a vital role in identifying the data that

has originated from the citizen’s side and how does it

further support any function of the service. For

instance, data collected from all geo-participation

approaches can be brought together to support

decision-making, service delivery and government

operation (Zhang, 2019). It is imperative to leverage

data requirements of both the government and the

citizens to produce techniques in order to provide

feedback and initiate secondary uses of geospatial

data. For instance, using data for Application

development, producing public services, etc. (Zhang,

2019). Likewise, Alizadeh et al ,(2019) analysed data

from social media (Twitter) where citizens discussed

their concerns on urban projects and leaving

meaningful observations that have the capacity to

inform the decision-making process. Recent

innovations in mobile, data, and cloud offer new

prospects for enhancing the quality of government

and governance and fulfil the expectations of citizens

(Linders, et al). The aim of open data is towards

improving government transparency, motivating

citizen participation and unlocking commercial

innovation (Ma & Lam, 2019). However, there are

many interlacing barriers which hinder the adoption

of open data for instance, the non-existence of a

public participation mechanism, unsatisfactory public

feedback and consumption statistics create the

stakeholders unknowing of the true requirements of

citizens (ibid).

2.4 Technology Layer

This layer focuses on supporting information and the

system/application functionality with the help of

technological components (Pourzolfaghar et al.,

2019). It provides advanced technologies supporting

citizen’s inputs with the help of information or

SMARTGREENS 2021 - 10th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

38

application functions in order to deliver effective

services to the citizens (ibid). While technology

provides cheap and effective ways to engage citizens

in addressing various issues, there is no replacement

for offline face-to-face engagement (Horgan &

Dimitrijević, 2019). Salvia & Morello, (2020) argued

that hybrid forms of interaction that combine online

and offline platforms, have an important role to play

in reaching citizens. Nonetheless, it is vital to

understand that the greater direct access to public

information may improve transparency and facilitate

citizen engagement, but at the same time it may

overwhelm citizens with too much information as

well (Lee, Lee-Geiller, & Lee, 2020; Jae &

Viswanathan, 2012). Textual information tended to

cause greater information overload, specifically for

those with an inclination for visual information

processing (Lee, Lee-Geiller, & Lee, 2020). El-

Haddadeh et al., (2019) highlighted that the use of

IoT, offers a unique opportunity to both governments

and citizens to work closely together in order to

improve current public services despite various

challenges associated with it. While citizens feel

empowered and add value to existing services

through consuming and co-creating, governments

will have the opportunity to utterly exploit the

potential of innovative technologies to better optimise

their distribution of public services (El-Haddadeh et

al., 2019). For example, senior citizens require

elderly-friendly urban environments along with

particular municipal services to respond to their

specific needs and we require technologies which can

fulfil such requirements (Jelokhani-Niaraki et al,

2019). In the above section, various platforms,

models and technology have been discussed which

support citizens in the development of smart cities.

This discussion highlights how current literature

supports citizens in the development and how their

feedback at service layer could be beneficial for

designing better quality of services.

3 IDENTIFIED RESEARCH GAP

The challenge in smart cities is to evaluate, design

and standardize new solutions, not only to ensure high

performance with respect to the technological

components, but also to ensure high levels of Quality

of Experience (QoE) as perceived by end users

(Ballesteros et al., 2015). Thus, there is a requirement

to improve the current performance of the services

with the aim of improving efficiency, usefulness and

quality of life for the citizens (ibid). In the previous

sections, it has been discussed how existing literature

supports citizens in the design of the smart city

services. However, it is not clear from the literature

how their feedback could assist in further design

improvement at the service layer; which is also

associated with the experience of the citizens and

performance of the services. In order to understand

this, a case study was conducted to analyse the

feedback of citizens during the later stages (i.e. After

the deployment of the service) at service layer and to

examine how this feedback could be transformed into

more structured requirements in order to provide

improved quality of the services to them. The service

layer has components which are associated with the

experience of the end users after delivering the

services. The aim of this study is also to understand

the research problem from citizen’s (users) viewpoint

and to examine their experience towards these

services, therefore this research specifically emphasis

on this layer for understanding their requirements in

more effective way.

4 CASE STUDY: E-PARKING

SERVICE

A case study approach investigates and explores a

contemporary phenomenon within its real-life

context, most specifically when the boundaries

between context and phenomenon is not clearly

evident (Yin, 2013). Therefore, an exploratory and

deductive case study approach was used to investigate

the research problem from the real environment. The

detail of the conducted case study can be found in

table 1 which has been designed according to the

template and guidance provided by (Greenwood,

2011; Baxter et al, 2008).

This case study is based on one of the smart

services (i.e. e-parking) provided by many of the

City/County Councils in the Republic of Ireland.

This service was chosen in order to understand how

Quality of Service (QoS) could be improved at

service level and to position citizen’s requirements in

more structured format at architecture level. In order

to conduct the case study, interviews were carried out

at the County Council with the key individuals

involved with this service. Additionally, online data

(review comments) was collected and analysed for a

smart service (e-parking) which allows users to pay

for their parking via an application platform. This

App requires registration details and vehicle related

information from the users. It does not require users

to display a parking disc while their car is parked.

Role of Citizens in the Development of Smart Cities: Benefit of Citizen’s Feedback for Improving Quality of Service

39

Table 1: Case Study Design on Smart Service Design.

Context: According to the literature citizen’s play vital

role in the design and development of the smart city

services in order to provide effective services to them.

Therefore, this study investigates their role in the design

of the smart city services in Irish context and highlights

existing issues from citizen’ end based on the feedback

they provided for one of the smart services in Ireland.

The Case: E-

p

arkin

g

service in Cit

y

/Counties of Irelan

d

Objective:

To understand the experience of citizens towards

this service.

To understand how requirements are provided to

design such smart city services.

Study Design: Exploratory deductive approach.

Data Collection: Interviews, online review comments

from end users.

Analysis: Qualitative data were analysed to identify the

challenges from citizen’s viewpoint and from Council’s

perspective. Based on this analysis, feedback was

classified against the associated requirements for other

layers of the architecture.

Key Findings:

The feedback obtained from the citizen’s end can be

useful in identifying a set of requirements for the

services.

Citizens have no formal role in the design of the

services that leads to lower quality of the service at the

end.

There is a lack of understanding how to incorporate

citizen’s feedback for designing the effective services.

There is a challenge in mapping citizen’s

re

q

uirements with existin

g

resources.

Other user benefits include saving their time with

hassle free parking and also reduce CO2 emission in

the environment. Based on the interviews carried out,

it was found that the there is a challenge in mapping

citizen’s requirements with existing available

resources (e.g. “...like major block is how do we map

their requirements...”). Despite the fact that there are

so many engagement programs be it offline or online,

it is still not clear if citizens have any formal role in

the design process of the services (e.g. “…. I am not

sure if there is any input from the citizens in the actual

design process of the services…”), on the other hand

requirements are usually provided by the Council to

service providers for designing any new service in the

City (e.g. “…...requirement for the existing services

are given by considering already implemented

similar systems in other locations….”). There are two

key issues which emerged from the interviews, first it

was not clear if citizens have any actual role in the

design of the services. Secondly, even if there are

various platforms to support their feedback, it is not

evident how those feedbacks are transformed into

more structured requirements for the service design.

To investigate this issue further from citizen’s end,

this study also analysed the review comments of end

users who were using the e-parking service. In order

to analyse the online review comments (textual data),

this study followed a thematic research approach

(Mason, 2002;Young and Hren, 2017). Which

followed the guidelines provided by (Braun & Clarke,

2012). Authors provided six phases to perform the

analysis of dataset and based on this methodology,

this study firstly read and reread the review comments

provided by end users and took notes on preliminary

ideas and thoughts about connecting those feedbacks

with their experience towards the service. During the

second phase, initial codes were formed which were

common among the data set, for instance people

Complaining about extra 1euro charge (E.g. “10%

top up fee without warning. Total scam”) were coded

as “No Information on Additional Charged Fees”.

Then as a part of third phase, codes were converted

into more organised themes which provide meaning

within dataset. The identified codes from phase two

were further linked to the predefined themes, for

instance the code “No Information on Additional

Charged Fees” has been classified as a Quality Factor

(Transparency) of the service which can further

provide guidance towards understanding and

structuring requirements from citizen’s end. The

fourth phase is about reviewing potential themes

whereby the developed themes are being reviewed

with respect to the coded data and the complete data

set. Therefore, all generated themes which are in

relation to the Quality factors of the service were

revised and checked to ensure if they belong to

correct category of the identified reviewed comment

or to other. In the fifth phase, the coded themes were

further linked to the identified requirements of the

service as described in table 2. In the final phase, the

analysis has been reported as a case study for e-

parking service. This analysis was carried out by

using Excel sheet which followed a method proposed

by (Bree and Gallagher, 2016). This methodology

describes the steps for analysing the data based on the

colour coding scheme provided in Excel. There were

around 46 review comments per county that were

being downloaded in the form of Excel sheet from the

app store using the website Heedzy

(https://heedzy.com). The review comments were

further analysed and classified against the factors

(Themes) associated with the Quality of Experience

(QoE) based on different coding colours, which

stems from the experience of user’s expectations with

respect to the utility of the application or service

SMARTGREENS 2021 - 10th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

40

(Ballesteros et al., 2015). After conducting this case

study, it was found that there are many engagement

programs and projects which involve citizens and

identify challenges from their end. However, it is not

evident how those challenges are further addressed in

order to meet their requirements. Furthermore, role of

citizens in the actual implementation of those services

is still vague which is in line with what has already

been emphasised by many researchers in the field

(Allen et al, 2020; Wolff et al, 2020; Heaton &

Parlikad, 2019; Sofiyabadi et al., 2016).

Table 2: Sample of Impacted Quality Factors,

Corresponding Themes, and their Links to Identified

Requirements.

Sample of Online

Reviews

(Source:

https://play.google.com/

store)

Codes

Identified Impacted

Quality Factors from

Service Layer (Themes)

A

ssociated Requirements

(Adopted from Bastidas

et al, (2018))

Link to Other Layers for

Associated Requirements

“App will not load so

cannot access my

account, nor can I park

my car. It's not an

internet issue as my

other apps work fine. I

uninstalled and then

reinstalled it and now it

won't let me log in as it

says there's no

available host... I rely

on this almost every

day and cannot believe

that this has happened”

Applica-

tion

Issue

Effectiveness Availability

/ Software

Engineerin

g Tools

Technol

ogy

“10% top up fee

without warning. Total

scam.”

No

Informa-

tion on

A

dditional

charged

Fees

Transparency Trust Context

“Charged a processing

fee for adding cash to

account. It's the last

time I'll be using this.”

No

Informa-

tion on

A

dditional

charged

Fees/

Usa

g

e

Transparency

/Usefulness

Trust/ City

Oriented

Context

/Inform

ation

“Appallingly bad. Only

used it a few times and

some of the roads don't

have a code applicable.

Also if you move to

another street within

the time you've to pay

again, whereas with the

disk you can use it for

the 2 hours (or whatever

the limit is in the area

)

.”

Applicati

on Issue

Personalisa-

tion

Flexibility Context/

Informat

ion

“It won't even accept

my car registration.

There's no guidance

p

rovided or feedback

the city council haven't

responded to emails

either.”

Applicati

on Issue

Usability Extensibili

ty

Informa

tion

5 CONCEPTUAL MODEL

In this paper, it has been discussed how existing

literature supports citizens in the development of the

smart city services. For instance, at context level,

citizens contribute their ideas for developing new

applications. At information and technology level,

various platforms and technologies have been

discussed which provide assistance in obtaining their

feedback and in designing new services based upon

the requirements of the citizens. It has been

highlighted that feedback at the service layer could

further guide smart city stakeholders in designing

better quality of services. Existing studies provide

various platforms to support citizen’s feedback in the

design of the smart city services. However, there is a

lack of understanding how those feedbacks are

utilised to design effective services for them.

Therefore, with this study it has been highlighted how

their feedback could be incorporated into more

structured format at architecture level. Based on

literature presented and the conducted case study, the

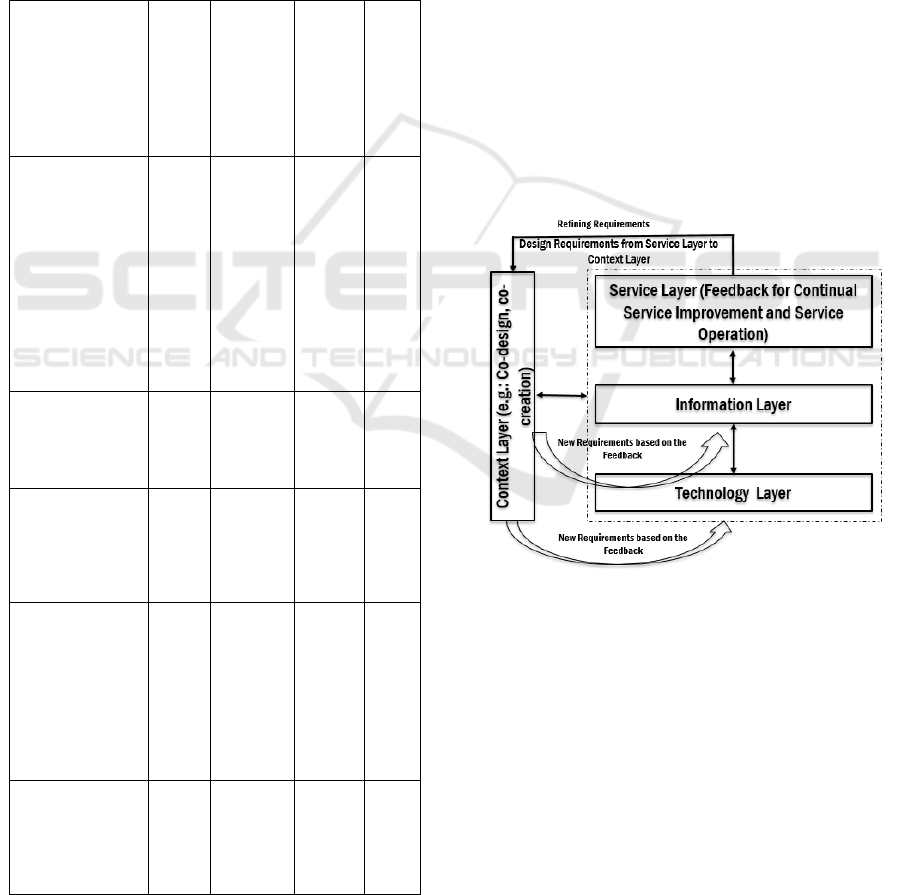

following conceptual model has been proposed

(Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual Model (Architectural Layers adopted

from Pourzolfaghar et al., (2019)).

This model indicates how identified quality factors

could assist in further refining the requirements for

the service. Based upon this model the identified

quality factors can be associated with the type of

requirements belonging to specific layer of the

architecture. For example, the effectiveness factor

(“………. I uninstalled and then reinstalled it and

now it won't let me log in as it says there's no

available host…………”) can be classified as

functional requirement (Software Engineering Tools)

in which smart city platforms are required to provide

Role of Citizens in the Development of Smart Cities: Benefit of Citizen’s Feedback for Improving Quality of Service

41

a set of tools for the development and maintenance of

services and applications. These tools can be

positioned in technology layer which focusses on

technological components and associated platforms

with it. Another concerning issue found from those

feedback was about additional fee that citizens were

charged without their knowledge (e.g. “….10% top

up fee without warning. Total scam….”) which is

associated with the Transparency quality factor and

could belong to context layer for classifying it as a

non-functional requirement (Trust) of the service.

Similarly, there were also some issues regarding the

application functionality (e.g. “.... Appallingly bad.

Only used it a few times and some of the roads don't

have a code applicable…”) and can assist in

understanding the application requirements of the

service which can be positioned in the information

layer. With the e-parking service example, it was

observed that the user satisfaction level was quite low

and their feedback at the service level can assist in

identifying the functional and non-functional

requirements of the service for other layers too. This

can further help City authorities and service providers

in designing better quality of the services by

considering the new requirements of the service.

Feedback could be accessed either via online apps

associated with the smart services or from other form

of social media platform where users could provide

their viewpoint and discuss the issues which are

associated with the services. In order to analyse the

feedback from the end users’ side, machine learning

algorithms could assist in classification process to

understand the experience of the users (Sharma &

Sharma, 2020). Moreover, requirement analysis

could be done based on the end user’s experience and

feedback by following a Conjoint analysis approach

(Kwon and Kim, 2007).

6 CONCLUSION AND FUTURE

WORK

It has been found that there are many offline and

online engagement programs, platforms, technologies

which obtain citizen’s feedback for the development

of smart city services. However, there is a lack of

understanding of how their feedbacks are transformed

into more structured requirements in order to design

effective services for the citizens. A case study was

conducted to examine the feedback of citizens and to

investigate their role in the design of the services.

Based upon which this study proposes a conceptual

model which elaborates how feedback could be

converted into more structured requirements at

architecture level which would further provide

guidance to smart city stakeholders in designing

better quality of services in the future. This would

ensure that citizen’s requirements are met based on

the received feedback from their end. As a part of

future work of this research, the aim is to evaluate the

proposed conceptual model and investigate the

missing constructs in the proposed model for

designing better quality of the services by

transforming citizen’s feedback into more structured

requirements at architecture level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported with the financial support

of the Science Foundation Ireland grant 13/

RC/2094_P2 and co-funded under the European

Regional Development Fund through the Southern &

Eastern Regional Operational Programme to Lero -

the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for

Software (www.lero.ie).

REFERENCES

Abella, A., Ortiz-De-Urbina-Criado, M., & De-Pablos-

Heredero, C. (2019). A methodology to design and

redesign services in smart cities based on the citizen

experience. Information Polity, 24(2), 183–197. https://

doi.org/10.3233/IP-180116.

Abu-Tayeh, G., Neumann, O., & Stuermer, M. (2018).

Exploring the Motives of Citizen Reporting

Engagement: Self-Concern and Other-Orientation.

Business and Information Systems Engineering, 60(3),

215–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-018-0530-8.

Alizadeh, T., Sarkar, S., & Burgoyne, S. (2019). Capturing

citizen voice online: Enabling smart participatory local

government. Cities, 95, 102400. https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.cities.2019.102400.

Allen, B., Tamindael, L. E., Bickerton, S. H., & Cho, W.

(2020). Does citizen coproduction lead to better urban

services in smart cities projects? An empirical study on

e-participation in a mobile big data platform.

Government Information Quarterly, 37(1), 101412.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.101412.

Alruwaie, M., El-Haddadeh, R., & Weerakkody, V. (2020).

Citizens’ continuous use of eGovernment services: The

role of self-efficacy, outcome expectations and

satisfaction. Government Information Quarterly, 37(3),

101485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.101485.

Andreani, S., Kalchschmidt, M., Pinto, R., & Sayegh, A.

(2019). Reframing technologically enhanced urban

scenarios: A design research model towards human

centered smart cities. Technological Forecasting and

Social Change, 142(September 2018), 15–25.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.09.028.

SMARTGREENS 2021 - 10th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

42

Ballesteros, L. G. M., Alvarez, O., & Markendahl, J.

(2015). Quality of Experience (QoE) in the smart cities

context: An initial analysis. 2015 IEEE 1st

International Smart Cities Conference, ISC2 2015.

https://doi.org/10.1109/ISC2.2015.7366222.

Baxter, P., Susan Jack, & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative Case

Study Methodology: Study Design and Implementation

for Novice Researchers. The Qualitative Report Vol.

13(4), 544–559. https://doi.org/10.2174/18744346008

02010058

Bednar, P. M., & Welch, C. (2019). Socio-Technical

Perspectives on Smart Working: Creating Meaningful

and Sustainable Systems. Information Systems Frontiers.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-019-09921-1.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. APA

Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2:

Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuro-

psychological, and Biological., 2, 57–71. https://

doi.org/10.1037/13620-004.

Bree, R., & Gallagher, G. (2016). Using Microsoft Excel to

code and thematically analyse qualitative data: a

simple, cost-effective approach. All Ireland Journal of

Higher Education, 8(2).

Brunswicker, S., Priego], L. [Pujol, & Almirall, E. (2019).

Transparency in policy making: A complexity view.

Government Information Quarterly, 36(3), 571–591.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.05.005.

Cellina, F., Castri, R., Simão, J. V., & Granato, P. (2020).

Co-creating app-based policy measures for mobility

behavior change: A trigger for novel governance prac-

tices at the urban level. Sustainable Cities and Society,

53, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.

101911

Clement, S. J., McKee, D. W., & Xu, J. (2017). Service-

Oriented Reference Architecture for Smart Cities.

Proceedings - 11th IEEE International Symposium on

Service-Oriented System Engineering, SOSE 2017, 81–

85. https://doi.org/10.1109/SOSE.2017.29.

Corsini, F., Certomà, C., Dyer, M., & Frey, M. (2019).

Participatory energy: Research, imaginaries and

practices on people’ contribute to energy systems in the

smart city. Technological Forecasting and Social

Change, 142(July 2018), 322–332. https://doi.org/1

0.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.028.

Dameri, R. P., Benevolo, C., Veglianti, E., & Li, Y. (2019).

Understanding smart cities as a glocal strategy: A

comparison between Italy and China. Technological

Forecasting and Social Change, 142, 26–41.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.

07.025.

De Guimarães, J. C. F., Severo, E. A., Felix Júnior, L. A.,

Da Costa, W. P. L. B., & Salmoria, F. T. (2020).

Governance and quality of life in smart cities: Towards

sustainable development goals. Journal of Cleaner

Production, 253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.

2019.119926.

Ekman, P., Röndell, J., & Yang, Y. (2019). Exploring smart

cities and market transformations from a service-domi

nant logic perspective. Sustainable Cities and Society,

51(February), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101731.

El-Haddadeh, R., Weerakkody, V., Osmani, M., Thakker,

D., & Kapoor, K. K. (2019). Examining citizens’

perceived value of internet of things technologies in

facilitating public sector services engagement.

Government Information Quarterly, 36(2), 310–320.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2018.09.009.

Greenwood, R. E. (2011). The Case Study Approach.

Business Communication Quarterly, 56(4), 46–48.

https://doi.org/10.1177/108056999305600409.

Habibzadeh, H., Nussbaum, B. H., Anjomshoa, F.,

Kantarci, B., & Soyata, T. (2019). A survey on

cybersecurity, data privacy, and policy issues in cyber-

physical system deployments in smart cities.

Sustainable Cities and Society, 50(August 2018),

101660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101660.

Heaton, J., & Parlikad, A. K. (2019). A conceptual

framework for the alignment of infrastructure assets to

citizen requirements within a Smart Cities framework.

Cities, 90(January), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

cities.2019.01.041.

Hollands, R. G. (2008). Will the real smart city please stand

up? City, 4813. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810802

479126.

Horgan, D., & Dimitrijević, B. (2019). Frameworks for

citizens participation in planning: From conversational

to smart tools. Sustainable Cities and Society, 48, https://

doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101550.

Jae, H., & Viswanathan, M. (2012). Effects of pictorial

product-warnings on low-literate consumers. Journal of

Business Research, 65(12), 1674–1682. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.02.008.

Janowski, T., Estevez, E., & Baguma, R. (2018). Platform

governance for sustainable development: Reshaping

citizen-administration relationships in the digital age.

Government Information Quarterly, 35(4, Supplement),

S1–S16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2018.09.002.

Jelokhani-Niaraki, M., Hajiloo, F., & Samany, N. N.

(2019). A Web-based Public Participation GIS for

assessing the age-friendliness of cities: A case study in

Tehran, Iran. Cities, 95, 102471. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.cities.2019.102471.

Ju, J., Liu, L., & Feng, Y. (2019). Public and private value

in citizen participation in E-governance: Evidence from

a government-sponsored green commuting platform.

Government Information Quarterly, 36(4), 101400.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.101400

Kopackova, H. (2019). Reflexion of citizens’ needs in city

strategies: The case study of selected cities of Visegrad

group countries. Cities, 84(August 2018), 159–171.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.08.004.

Kumar, H., Singh, M. K., Gupta, M. P., & Madaan, J.

(2020). Moving towards smart cities: Solutions that

lead to the Smart City Transformation Framework.

Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 153.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.04.024.

Kwon, O., & Kim, J. (2007). A methodology of identifying

ubiquitous smart services for U-City development.

Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including

Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and

Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 4611 LNCS(July),

Role of Citizens in the Development of Smart Cities: Benefit of Citizen’s Feedback for Improving Quality of Service

43

143–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-73549-

6_15

Lee, T. (David), Lee-Geiller, S., & Lee, B. K. (2020). Are

pictures worth a thousand words? The effect of

information presentation type on citizen perceptions of

government websites. Government Information

Quarterly, 37(3), 101482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

giq.2020.101482.

Linders, D., Liao, C. Z.-P., & Wang, C.-M. (2018).

Proactive e-Governance: Flipping the service delivery

model from pull to push in Taiwan. Government

Information Quarterly, 35(4, Supplement), S68–S76.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.08.004.

Lorquet, A., & Pauwels, L. (2020). Interrogating urban

projections in audio-visual ‘smart city’ narratives.

Cities, 100, 102660. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.

1016/j.cities.2020.102660.

Ma, R., & Lam, P. T. I. (2019). Investigating the barriers

faced by stakeholders in open data development: A study

on Hong Kong as a “smart city.” Cities, 92, 36–46.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.03.009.

Macke, J., Rubim Sarate, J. A., & de Atayde Moschen, S.

(2019). Smart sustainable cities evaluation and sense of

community. Journal of Cleaner Production, 239.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118103.

Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative Researching (Second). SAGE

Publications.

Minoli, D. (2008). Enterprise architecture A to Z:

frameworks, business process modeling, SOA, and

infrastructure technology. CRC press.

Nakamura, H., & Managi, S. (2020). Effects of subjective

and objective city evaluation on life satisfaction in

Japan. Journal of Cleaner Production, 256, 120523.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.1

20523.

Nam, T., & Pardo, T. A. (2011). Smart city as urban

innovation. In Proceedings of the 5th International

Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic

Governance - ICEGOV ’11 (p. 185). https://doi.org/

10.1145/2072069.2072100.

Pedersen, K. (2020). What can open innovation be used for

and how does it create value? Government Information

Quarterly, 37(2), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2020.

101459.

Pourzolfaghar, Z., Bastidas, V., & Helfert, M. (2019).

Standardisation of enterprise architecture development

for smart cities. Journal of the Knowledge Economy.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-019-00601-8.

Salvia, G., & Morello, E. (2020). Sharing cities and citizens

sharing: Perceptions and practices in Milan. Cities, 98,

102592. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities

.2019.102592.

Schröder, P., Vergragt, P., Brown, H. S., Dendler, L.,

Gorenflo, N., Matus, K., … Wennersten, R. (2019).

Advancing sustainable consumption and production in

cities - A transdisciplinary research and stakeholder

engagement framework to address consumption-based

emissions and impacts. Journal of Cleaner Production,

213, 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018

.12.050.

Sharma, P., & Sharma, A. K. (2020). Experimental

investigation of automated system for twitter sentiment

analysis to predict the public emotions using machine

learning algorithms. Materials Today: Proceedings,

(xxxx). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.09.351.

Sofiyabadi, J., Kolahi, B., & Valmohammadi, C. (2016).

Key performance indicators measurement in service

business: a fuzzy VIKOR approach. Total Quality

Management and Business Excellence, 27(9–10),

1028–1042. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2015

.1059272.

Solaimani, S., Bouwman, H., & Itälä, T. (2015). Networked

enterprise business model alignment: A case study on

smart living. Information Systems Frontiers, 17(4),

871–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-013-9474-1.

Vidiasova, L., & Cronemberger, F. (2020). Discrepancies

in Perceptions of Smart City Initiatives in Saint

Petersburg, Russia. Sustainable Cities and Society,

102158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.

2020.102158.

Wataya, E., & Shaw, R. (2019). Measuring the value and

the role of soft assets in smart city development. Cities,

94,106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.04.019

Wolff, A., Barker, M., Hudson, L., & Seffah, A. (2020).

Supporting smart citizens: Design templates for co-

designing data-intensive technologies. Cities, 101.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102695.

Yigitcanlar, T., Foth, M., Sabatini-marques, J., & Ioppolo,

G. (2019). Can cities become smart without being

sustainable ? A systematic review of the literature.

Sustainable Cities and Society, 45(June 2018), 348–

365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.11.033.

Young, B., & Hren, D. (2017). Introduction to qualitative

research methods. The Second MiRoR Training Event.

Zhang, S. (2019). Public participation in the Geoweb era:

Defining a typology for geo-participation in local

governments. Cities, 85, 38–50. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.cities.2018.12.004.

SMARTGREENS 2021 - 10th International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems

44