Retailer’s Dual Role in Digital Marketplaces: Towards Architectural

Patterns for Retail Information Systems

Tobias Wulfert

a

and Reinhard Sch

¨

utte

b

Institute for Computer Science and Business Information Systems, University of Duisburg-Essen,

Universit

¨

atsstraße 2, Essen, Germany

Keywords:

Digital Marketplace, Architectural Pattern, Retail Information System, Electronic Commerce, Design Science

Research.

Abstract:

Multi-sided markets (MSMs) have entered the retail sector as digital marketplaces and have proven to be a

successful business model compared to traditional retailing. Established retailers are increasingly establishing

MSMs and also participate in MSMs of pure online companies. Retailers transforming to digital marketplaces

orchestrate formerly independent markets and enable retail transactions between participants while simulta-

neously selling articles from an own assortment to customers on the MSM. The retailer’s dual role must be

supported by the retail information systems. However, this support is not explicitly represented in existing

reference architectures (RAs) for retail information systems. Thus, we propose to develop a RA for retail in-

formation systems facilitating the orchestration of supply- and demand-side participants, selling own articles,

and providing innovation platform services. We apply a design science research approach and present seven

architectural requirements that a RA for MSM business models needs to fulfill (dual role, additional partici-

pants, affiliation, matchmaking, variety of services, innovation services, and aggregated assortment) from the

rigor cycle. From a first design iteration we propose three exemplary, conceptual architectural patterns as

a solution for three of these requirements (matchmaking for participants, innovation platform services, and

aggregated assortment).

1 INTRODUCTION

Catalyzed by the implications of the Covid-19 pan-

demic, the electronic commerce (ecommerce) rev-

enue is expected to increase worldwide and across

sectors by more than 20 percent compared to 2019

(Rotar, 2020). In Europe it already accounts for 374

billion euros in total. As customers are only willing to

shop at brick-and-mortal (BaM) retailers if they feel

safe, they increasingly tend to shop groceries, apparel,

jewelry etc. online and aim for digital end-to-end cus-

tomer journeys (Bhatti et al., 2020; McKinsey, 2020;

Dietz et al., 2020). Additional governmental decrees

to close BaM shops force retailers to (hazardly) es-

tablish additional online sales channels and transform

their value proposition for digital platforms (Nicola

et al., 2020; Dietz et al., 2020). Indeed, the pandemic

drives the digital transformation in retail and whole-

sale that previously neglected necessary digitalization

endeavors (Sch

¨

utte and Vetter, 2016).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5504-0718

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1535-9038

Besides the possibility of establishing electronic

shops (eshops), retailers and wholesalers may also

participate in existing or build up own digital mar-

ketplaces that establish digital multi-sided markets

(MSMs) (Van Alstyne et al., 2016; Hagberg et al.,

2016; Staykova and Damsgaard, 2015). While eshops

act as resellers in a single market, digital marketplaces

connect previously independent markets, match indi-

vidual participants from the MSMs, and enable (re-

tail) transaction between them (Hagiu and Wright,

2015). Digital marketplaces orchestrate multiple mar-

kets and thus simplify the interaction with suppli-

ers, logistic service providers, market researchers and

other actors (H

¨

anninen, 2018). They focus on the

monetization of the matchmaking instead of sell-

ing articles with higher margins (Evans and Gawer,

2016; Ivarsson and Svahn, 2020; Choudary, 2015).

The orchestration causes (merely indirect) network

effects for market participants (Shapiro and Varian,

1998) and marketplace owners implement asymmet-

ric pricing mechanisms for monetizing the match-

making (Armstrong, 2006; Rochet and Tirole, 2003).

Wulfert, T. and Schütte, R.

Retailer’s Dual Role in Digital Marketplaces: Towards Architectural Patterns for Retail Information Systems.

DOI: 10.5220/0010405306010612

In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2021) - Volume 2, pages 601-612

ISBN: 978-989-758-509-8

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

601

Although traditional retail companies act as market

intermediaries who offer manufacturers’ products to

customers (reseller mode), the development of dig-

ital marketplaces for the implementation of MSMs

(as generalization of tow-sided markets) has not been

driven by retail, but usually by technology compa-

nies. There are several examples of the tremendous

success of digital marketplaces such as Amazon, Al-

ibaba and eBay which orchestrate MSMs (Sch

¨

utte,

2018). It seems unusual that although retailers are

a significant factor in any economy and have tradi-

tionally linked markets (e.g. producer and consumer

markets) for a long time (Levy et al., 2019), the ex-

pansion via MSMs was not driven by retailers. So

far only a few large retail companies have established

their own MSMs (e.g. Walmart, REWE). As digi-

tal marketplaces often form the preferred touchpoint

for many customers and marketplace owners encapsu-

late manufacturers from customers, retailers need to

establish their own MSMs (McKinsey, 2020; Rotar,

2020). If the owner of a digital marketplace behaves

neutral (Kawa and Wałe¸siak, 2019; Wang and Archer,

2007), he does not gain ownership of the traded arti-

cles (in contrast to e-shops) at any point of the transac-

tion (Hagiu, 2007). It facilitates retail transactions be-

tween ecosystems participants by providing interfaces

for the interaction (Williamson, 1985). In contrast,

competitive marketplace owners possess a dual role

and also offer own articles on the digital marketplace

(Kawa and Wałe¸siak, 2019; T

¨

auscher and Laudien,

2018). They may compete with other supply-side par-

ticipants offering similar articles. This dual role as

marketplace owner and competitor selling own arti-

cles in the MSM causes additional requirements for

RIS to support them (Wulfert et al., 2021). Although

the importance of MSM business models seems to

grow, existing literature only focuses on the adaption

of business models and respective tools to model them

(Evans and Gawer, 2016; Reillier and Reillier, 2017).

Consequences of the retailer’s dual role for underly-

ing RIS – the digital infrastructure for ecommerce –

supporting the specifics of ecommerce and interme-

diary business model of MSMs are rarely considered

(Aulkemeier et al., 2016; Wulfert et al., 2021). A ref-

erence architecture (RA) may help to decrease setup

time for the digital infrastructure supporting MSMs

and standardize processes and interfaces (Angelov

et al., 2012). This standardization may ease the partic-

ipation in the MSM (Eaton et al., 2015) and increase

network effects (Shapiro and Varian, 1998). Although

domain-specific RAs for the retail sector such as the

retail-H (Becker and Sch

¨

utte, 2004) or ARTS-model

(APQC, 2019; OMG, 2019) do exist, literature deal-

ing with domain-specific RAs for ecommerce in gen-

eral (Aulkemeier et al., 2016) and retailer’s dual role

on digital marketplaces in particular is sparse accord-

ing to our thorough research. Thus, we will address

this research gap by deriving architectural require-

ments (AR) for RIS caused by the transformation of

a retailer in reseller mode to a marketplace owner and

present focal architectural patterns coping with these

ARs. For the analysis of ARs for MSMs and de-

velopment of architectural patterns, the focus will be

on the combination of three aspects: the orchestra-

tion of formerly independent markets in the sense of

MSMs (Armstrong, 2006; Caillaud and Jullien, 2003;

Haucap and Heimeshoff, 2018; Rochet and Tirole,

2003), competitive marketplace owners selling own

articles(Kawa and Wałe¸siak, 2019; Hagiu, 2007), and

the establishment of digital platforms from a technical

software perspective (Gawer and Henderson, 2007;

Tiwana et al., 2010). The architectural patterns will

include aspects of technology platforms centering the

marketplace owner’s RIS as central technological ar-

tifact upon which further modules can be developed

(Gawer and Henderson, 2007; West, 2003). For deriv-

ing ARs we follow a design science research (DSR)

approach (Peffers et al., 2007) with the architectural

patterns as artifacts (March and Smith, 1995). We use

ArchiMate (Open Group, 2019) as language for mod-

eling enterprise architectures to formally present the

architectural patterns in a “unified, unambiguous, and

widely understood domain terminology” (Nakagawa

et al., 2011). For the presentation of the architectural

patterns, we will focus on business and application

layer.

This research paper is structured as follows:

firstly, we introduce related literature concerning ar-

chitectural patterns in information systems (IS) ar-

chitecture and MSMs in ecommerce presenting seven

ARs. Secondly, we sketch our research approach for

deriving architectural patterns. Thirdly, we present

three exemplary architectural patterns and elicit on

additional architectural considerations for digital mar-

ketplaces. Finally, we discuss our architectural pat-

terns and summarize our results.

2 RELATED LITERATURE

2.1 IS Architecture and Patterns

Retail information systems (RIS) include all ap-

plication systems that are used to support opera-

tional tasks in retail. RIS support the execution of

the main trading functions and related tasks bridg-

ing the discrepancies in the streams between man-

ufacturers and customers in real goods (goods, ser-

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

602

vices; returns), nominal goods (money, credits) and

information across space, time, quantity and qual-

ity (Levy et al., 2019; Barth et al., 2015). In-

deed, RIS support the operational-dispositive, the

business administration-administrative, the control-

ling, and corporate planning tasks (Becker and

Sch

¨

utte, 2004). Besides the merchandise manage-

ment (merchandise planning, logistics and settlement

processes), RIS also support business intelligence and

necessary corporate-administrative tasks in an inte-

grative manner (Sch

¨

utte, 2017). Facilitated by the on-

going digitalization of the retail sector, the bridging

functions increasingly cope with digital product and

price information and adaptations in payment, logis-

tics and distribution processes (Becker and Sch

¨

utte,

2004; Sch

¨

utte and Vetter, 2016). In ecommerce trad-

ing transaction are carried out digitally to some degree

(Laudon and Traver, 2019). Thus, they build digital

infrastructures for executing the trading function in

online and offline environments.

An IS architecture “is a set of high-level models

which complements the business plan in IT-related

matters and serves as a tool for IS planning and

a blueprint for IS plan implementation” (Willcocks

et al., 1997). IS Architectures comprise a high-level

sketch of the system and application architecture of

a specific company and part of its application archi-

tecture (Heinrich and Stelzer, 2009). While concrete

IS architectures are dealing with one particular com-

pany, RAs abstract from the company’s peculiarities,

therefore enabling the reuse of architecture compo-

nents, providing an agreed upon set of concepts and

architectural patterns and communicating fixed view-

points (Giachetti, 2010). The development of a RA is

often inspired by concrete architectures or other arti-

facts and thus has a “descriptive nature” (Galster and

Avgeriou, 2011). However, developing a RA based

solely on existing research in a prescriptive manner

allows to create “a futuristic view of a class of sys-

tems” (Galster and Avgeriou, 2011). Research-based

RAs focus on the clarification of innovative patterns

and aim to convince domain architects of the architec-

ture qualities. Consequently, concrete systems can be

developed according to this research-based architec-

ture (Angelov et al., 2008). RAs are either applied to

standardize existing systems to ensure interoperabil-

ity or to facilitate the design and improve the qual-

ity of a concrete architecture with architectural guide-

lines (Angelov et al., 2009; Angelov et al., 2008).

They can be used as a starting point for company-

specific models to reduce the effort of creating those

through reuse of already established artifacts and con-

structs (Winter and Fischer, 2006). A domain-specific

RA is a reference model on a high level of abstraction

that provides a view of the essential areas of a domain

(e.g. AUTOSAR) without having to consist of com-

plete process and data models (Nakagawa et al., 2011;

Galster and Avgeriou, 2011). A RA is the mapping of

a process and data models functionality onto system

modules (Galster, 2015). Domain-specific IS refer-

ence architectures for the retail sector offer a high-

level view on architecture components and business

functions.

A RA consists of several architectural patterns

(Cloutier et al., 2010; Shaw and Garlan, 1996). These

patterns are defined as “named collection of architec-

tural design decisions that are applicable to a recur-

ring design problem” (Taylor et al., 2010). These pat-

terns are reusable solutions to common architectural

problems within a given domain (Shaw and Garlan,

1996). Additionally, architectural patterns are often

parameterized so that they can be applied to specific

problems in different organizational contexts (Taylor

et al., 2010). The relation between reference model

and architectural patterns as building block of the RA

and its manifestation in a concrete architecture for a

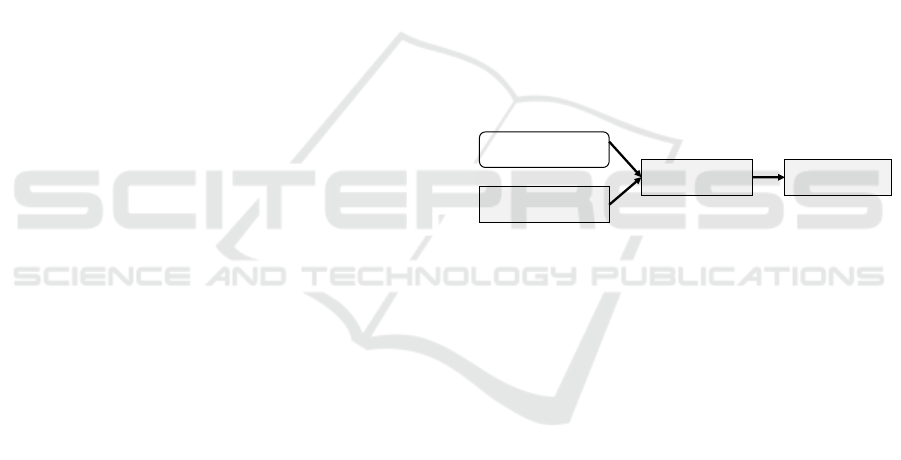

company are illustrated in figure 1.

Reference

Model

Architectural

Pattern

Reference

Architecture

Concrete

Architecture

Relationship between

RA, RM und Pattern

(Bass 2003)

Figure 1: Relation between Architecture Types (Bass et al.,

2003).

2.2 Digital Marketplaces

Introducing digital multi-sided markets (MSMs) in

ecommerce, we draw on the concept of two-sided

markets (Armstrong, 2006; Hagiu and Wright, 2015).

Digital marketplaces match two or more previously

distinct markets and exploit direct and indirect net-

work effects to further propel the MSM (e.g. one

side of the market subsidizing the other (Armstrong

and Wright, 2007; Rochet and Tirole, 2003)). While

MSMs predominantly operated in the B2C- and C2C-

modes, they are starting to be used for B2B trans-

actions more frequently (Li and Penard, 2014). Al-

though the concept of MSMs is also present in BaM

retail with shopping malls or variants of trading such

as agency trade (Abhishek et al., 2016) and commis-

sion business (M

¨

uller-Hagedorn et al., 2012), network

effects for participants (lower transaction costs for

search and initiation) and economies of scale for mar-

ket owners (marginal costs for adding another sup-

plier or article are almost zero) are even stronger in

ecommerce.

Retailer’s Dual Role in Digital Marketplaces: Towards Architectural Patterns for Retail Information Systems

603

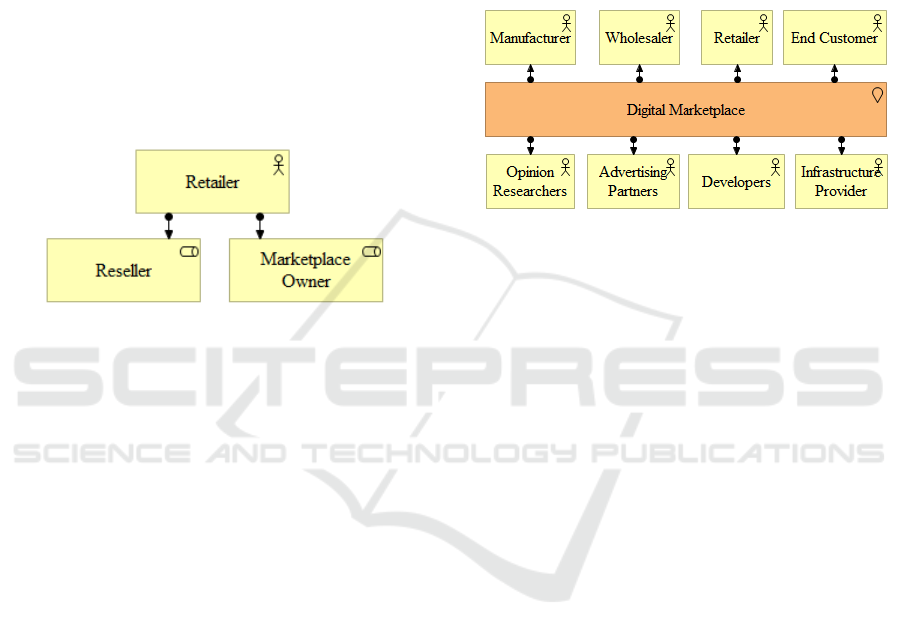

AR1: Retailer’s Dual Role. Besides taking a neu-

tral role by merely facilitating the matchmaking, the

marketplace owner can also behave competitively

to supply-side participants offering its own articles

to demand-side participants (Wulfert et al., 2021).

H

¨

anninen et al. distinguish pure multi-sided dig-

ital platform business models that merely facilitate

the matching between supply- and demand-side (e.g.

eBay, Alibaba, Rakuten) and MSM business models

that extend their own range of articles with indepen-

dent suppliers and offer further services to them (e.g.

Amazon) (Li et al., 2019; H

¨

anninen, 2018). The fo-

cus of this research paper is on the retailer’s dual role

as simultaneous marketplace owner and reseller com-

petitive to other supply-side participants (Figure 2).

Additionally, marketplaces can be established on the

Figure 2: Retailer’s Dual Role.

basis of existing BaM stores or eshops as additional

sales or procurement channel (Kawa and Wałe¸siak,

2019). The marketplace owner can be either one (e.g.

Walmart Marketplace) or a conglomerate of the par-

ticipants (e.g. Opodo) or even an independent third-

party (e.g. eBay) (Wang and Archer, 2007). Require-

ment: The RA needs to support both, the orchestra-

tion of the market sides (Reillier and Reillier, 2017)

and traditional bridging functions with related tasks

(Levy et al., 2019; M

¨

uller-Hagedorn et al., 2012).

AR2: Additional Types of Participants. For the

development of architectural patterns, we focus on

the two most important market sides, suppliers (man-

ufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers) and customers

(end- customers and retailers). In general, we de-

scribe a two-sided market as a specific manifestation

of a MSM in ecommerce (Hagiu and Wright, 2015).

Moreover, we also integrate third-party developers

and infrastructure providers to support the innovation

platform perspective (Tiwana et al., 2010; Gawer and

Henderson, 2007). Possible additional markets sides

are, among others, advertising partners, logistics ser-

vice providers or opinion research agencies. MSMs

differ from the traditional value chain of (offline) re-

tailers and eshops insofar, as that MSMs match man-

ufacturers on the supply-side with end customers on

the demand-side. Retailers and wholesalers may in-

teract with a digital marketplace as a supplier or may

demand articles from the MSM that is controlled by

the marketplace owner (Figure 3). The digital mar-

ketplace is modeled as location on which the match-

ing and (parts of) the transaction are executed (Turban

et al., 2017; Grieger, 2003). Requirement: The differ-

ent participants within a MSM need to be represented

adequately in terms of master data and records need to

ensure that transactions between them can be tracked

to optimize future matchmaking.

Figure 3: Participants of a Digital Marketplace.

AR3: Affiliation to the Marketplace. In the of-

fline environment retailers try to establish relations

with their customers offering e.g. optional loyalty

cards or apps (Hanke et al., 2018; Rudolph et al.,

2015) Hagiu and Wright argue that the participants of

a MSM always require some affiliation with it. How-

ever, the way in which the MSM participants must af-

filiate is not further defined and can be interpreted dif-

ferently (e.g. contract, membership, cookies) (Hagiu

and Wright, 2015). The affiliation is important to im-

prove the likelihood and quality of the matching as

it requires information about the participants (Evans

and Schmalensee, 2016; Reillier and Reillier, 2017).

Requirement: The affiliations of the different partic-

ipants and multiple market sides need to be repre-

sented and linked to participant profiles to support and

improve the matchmaking.

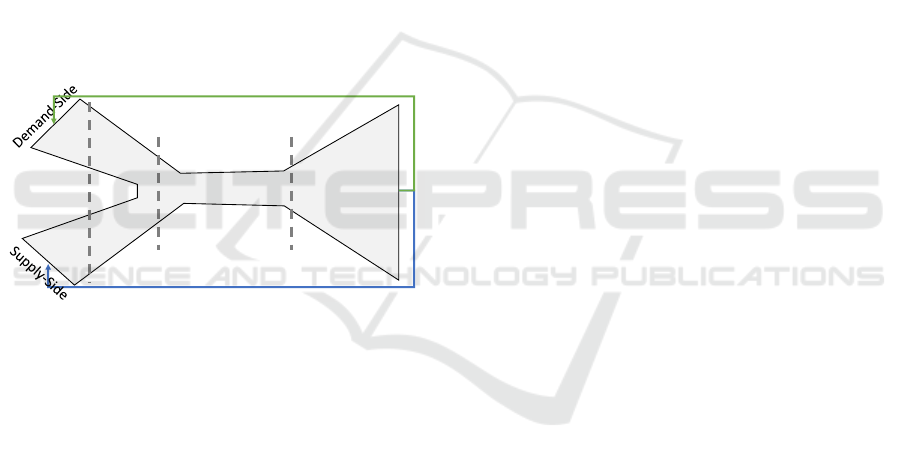

AR4: Matching as Core Value Proposition. As

already mentioned, the orchestration of formerly in-

dependent market sides is the core value proposition

of a digital marketplace (Armstrong, 2006; Evans and

Schmalensee, 2016; Rochet and Tirole, 2003; Ro-

chet and Tirole, 2006). This involves the match-

ing of single participants of the MSMs (Moazed and

Johnson, 2016). The matching can be described ac-

cording to Reillier and Reillier as a process of at-

tracting, matching, and connecting participants to en-

able (retail) transaction between them. The transac-

tion process and matching are optimized afterwards

(Reillier and Reillier, 2017). The matching between

supply- and demand-side participants can be illus-

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

604

trated in a schematic two-sided sales funnel (Figure

4) as an extension of the ecommerce sales funnel

(Blank and Dorf, 2012). In the attract phase, both

supply- and demand-side participants are acquired

and activated while already existing participants are

tried to retain. For matching both sides, the partici-

pants need to be introduced to each other considering

their characteristics captured within the participants

affiliation with the MSM. The assortment of supply-

side participants has to match the purchase desire of

demand-side participants and the digital marketplace

should provide appropriate matching partners (Evans

and Schmalensee, 2016). Next both participants need

to be connected to execute a retail transaction that can

be coordinated by the marketplace owner. Finally, the

transaction is optimized in order to transact further

articles within this matched pair or derive insights for

further transactions between other participants (Reil-

lier and Reillier, 2017; Blank and Dorf, 2012). Re-

quirement: The matching process needs to be sup-

ported by both, business and application services.

Match Connect & Transact

OptimizeAttract

Figure 4: Matching Market Sides in Ecommerce.

AR 5: Diversity of Services. Digital marketplaces

differ with regards to the type, scope, and coverage of

services offered by the marketplace owner (Wulfert

et al., 2021). When adding additional services, mar-

ketplace owners enhance their core value proposition.

The degree of additional services offered by a dig-

ital marketplace varies on a continuum between the

passive matching (e.g. eBay classifieds) to full ser-

vice offerings with sales processing, fulfillment ser-

vices and training services (e.g. Amazon) (Wang and

Archer, 2007; Wulfert et al., 2021). With regards

to the main bridging function (Levy et al., 2019),

a substantial amount of them may be performed by

other MSM participants or the marketplace owner de-

pending on the degree of centralization of the MSM

(Hein et al., 2016; Wang and Archer, 2007). As

MSM typically mature by offering additional services

(e.g. Amazon, eBay) (Reillier and Reillier, 2017),

RIS should be flexible to support the integration of

further services carried out by the MSM. A modu-

lar design will also support the service continuum of

MSM from pure-matchmaking to innovative market-

places. Requirement: The RA should be defined in a

flexible and modular way, so it supports the develop-

ment and integration of services that are not yet part

of the business model but are likely to be integrated in

the further evolution of the MSM.

AR6: Innovation Platform Services. Besides

trading-related services, digital marketplaces can also

offer innovation platform services for the marketplace

participants like access to sales data or smart product-

related data or remote services not associated with the

core trading business (Tiwana et al., 2010). These

services can also be compute power, storage, or de-

velopment environments like Amazon provides with

its Web Services that originated from the variability

of demand on computing resources in the ecommerce

business (Wittig et al., 2016). Innovation services

are the technical capabilities that enable the creation

of new solutions (services or software modules) by

participating third-party developers (Asadullah et al.,

2018). Integrating both transaction and innovation

services, the digital marketplace resembles an inte-

grated platform (Evans and Schmalensee, 2016) The

power of innovation platforms rests on their architec-

tural modularity (Baldwin and Clark, 2000; Tiwana

et al., 2010), catalyzing re-configurability of techni-

cal and organizational components to accelerate gen-

erativity and value creation. The components of sin-

gle modules are strongly interconnected but weakly

connected with the central platform through techni-

cal boundary resources (Baldwin and Clark, 2000; Ti-

wana, 2015). To enable the development of external

modules or apps by external developers and make use

of the development environment provided by the in-

novation platform, platform providers open their plat-

form and implement technical (e.g. APIs and SDKs)

and provide social (e.g. documentation and technical

support) boundary resources. External modules make

use of technical boundary resources provided by the

innovation platform (Eaton et al., 2015; Ghazawneh

and Henfridsson, 2013). Requirement: The RA needs

to include these innovation platform services and re-

spective boundary resources to enable developers to

exploit the offered services.

AR7: Digitally Aggregated Assortment. Digital

marketplaces aggregate a digital representation of the

diverse assortment of articles offered by supply-side

participants. The assortment can be described as the

periphery of the MSM while the core is the MSM it-

self offering services to supply- and demand-side par-

ticipants as described analogously in the platform lit-

Retailer’s Dual Role in Digital Marketplaces: Towards Architectural Patterns for Retail Information Systems

605

erature (Baldwin and Woodard, 2009; Staykova and

Damsgaard, 2015). From a customer point-of-view

MSMs “resemble retail agglomerations” (H

¨

anninen,

2018) integrating the range of articles of participat-

ing suppliers, retailers and wholesalers through a sin-

gle digital channel (Teller and Elms, 2010). Thus,

digital marketplaces further reduce transaction costs

(Williamson, 1985) for participants as a variety of

articles can be sold or purchased via a single touch-

point with a consistent user experience. Digital mar-

ketplaces also reduce the number of intermediaries to

participate in a single customer journey and uniform

boundary resources (Eaton et al., 2015; Ghazawneh

and Henfridsson, 2013). Ecommerce in general and

the aggregation of the individual assortments of var-

ious supply-side participants require a digital repre-

sentation of the articles within the assortment (Turban

et al., 2017). Requirement: The RA should include a

flexible model of the article master data to allow the

aggregation of the assortments.

3 RESEARCH APPROACH

For developing architectural patterns for RIS support-

ing the orchestration of MSMs, different types of par-

ticipants in ecommerce, and innovation platform ser-

vices, we apply a DSR approach as presented in figure

5 (Peffers et al., 2007). The problem-initiated process

starts with the problem (1) already stated in the intro-

duction. The objectives of the artifact (2) to be devel-

oped are the ARs as derived in section 2.2. Exemplary

architectural patterns as a solution (3) to the problem

will be presented in the next section. An evaluation

based on informed arguments (Hevner et al., 2004) is

contained in the discussion section.

Scientific Approach for

Design Science Research

in IS (Peffers et al. 2007,

p. 54)

2) Define

Objectives of

a Solution

1) Identify

Problem &

Motivate

3) Design &

Develop

4)

Demonstration

5) Evaluation 6) Communi-

cation

Process Iteration

Figure 5: DSR Approach (Peffers et al., 2007).

The outcome of the DSR approach is a model

(March and Smith, 1995) or more particular (parts

of) an architecture (Vaishnavi et al., 2019). Devel-

oped as “meta-artifacts” (Iivari, 2003), the architec-

tural patterns represent a “general solution concept”

(Van Aken, 2004) that is applicable to a class of prob-

lems when instantiated in the context of electronic

retail (March and Smith, 1995). The architectural

patterns (artifacts) are a new solution for an already

known problem and thus resemble an improvement

(Gregor and Hevner, 2013). These patterns can de-

scribe major tasks of a digital marketplace and present

them in a formal and understandable manner apply-

ing a highly regarded enterprise architecture model-

ing language (i.e. ArchiMate). A DSR should go

through three cycles (Hevner and Chatterjee, 2010).

While the focus of our overarching research is devel-

oping and evaluating a RA supporting digital market-

places in ecommerce with transaction and innovation

functions (Evans and Gawer, 2016), this design cy-

cle presents exemplary architectural patterns pivotal

to MSM business models in ecommerce. Our research

approach can be summarized as follows: Firstly, we

derive ARs based on a prior literature analysis as pre-

sented in section 2.2 (rigor cycle). Secondly, we de-

velop conceptual architectural patterns as general so-

lution concepts for these requirements (Iivari, 2015).

Hence, we develop domain-specific architectural pat-

terns as building blocks of an overarching RA based

on literature (Galster and Avgeriou, 2011; Angelov

et al., 2008). This design cycle focuses on deriving

architectural patterns from the rigor cycle and model-

ing them in ArchiMate. The literature-based architec-

tural patterns can then also be used as additional arti-

fact when analyzing existing RAs for retail in general

and ecommerce in particular. For a future relevance

cycle, we will conduct interviews with IT architects

and responsible IT staff architecting (parts of) an or-

ganization’s (IS) architecture. The retailer’s dual role

and additional innovation services (Gawer and Hen-

derson, 2007; Tiwana et al., 2010) cause additional

requirements for RIS that need to be reflected in RAs

for ecommerce. Thus, we present three exemplary ar-

chitectural patterns for these additional requirements

(AR5-7) not met by existing domain-specific RAs.

4 ARCHITECTURAL PATTERNS

4.1 Pattern 1: Matching of Participants

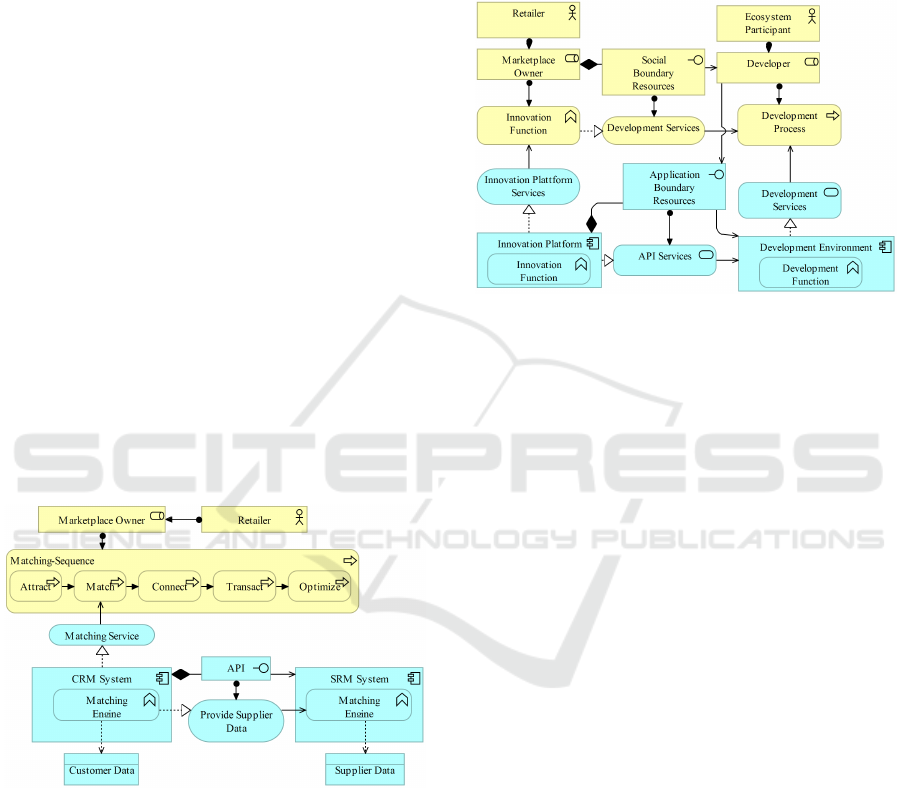

The first exemplary architectural pattern address-

ing AR5 is concerned with the matchmaking be-

tween participants from different market sides as

core value proposition of a digital marketplace (Arm-

strong, 2006; Choudary, 2015). The matching se-

quence as illustrated in figure 6 is executed by the re-

tailer or wholesaler in its role as marketplace owner.

The matching process is embedded in the matching

sequence as proposed by Reillier and Reillier (2017)

and introduced in section 2.2. After the attraction

of supply- and demand-side participants, participants

from independent markets need to be matched. In the

context a customer’s desire usually leads to a prod-

uct search either via search query or category search

(Kotler and Keller, 2016). Based on the customer’s

preferences stored in the customer data, the matching

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

606

engine situated in the customer and supplier relation-

ship management systems calculate the order of the

listed assortment. Thus, the relevance with regards

to the search term is not the only factor when listing

articles as a result of the customer’s query, the pre-

ferred supplier may also be considered. Matching par-

ticipants from supply and demand side of the MSM

requires an interface between these independent sys-

tems to exchange supplier and customer data relevant

for the matching. The listing of the assortment is an

important internal driver for retailers to increase rev-

enues in ecommerce (Chen et al., 2014). On digital

marketplaces the product listing is even further com-

plicated by the retailer’s dual role causing the ques-

tion whether to prefer products from the own assort-

ment or from another ecosystem participant’s assort-

ment. A higher priority for the owner’s assortment

cannot be implemented because of antitrust law con-

siderations (Bundeskartellamt, 2015). The matching

can be initiated proactively to stimulate a customer’s

desire (e.g. customized newsletters, social media mar-

keting, search engine advertising). After a match has

been created successfully, the retail transaction can be

executed. To optimize the matching sequence, sup-

plier and customer data are enriched with information

derived from the executed past transaction and other

demand-side participants from the same cluster may

get notified of the previous transaction.

Figure 6: Matching as Core Value Proposition.

4.2 Pattern 2: Innovation Services

The second exemplary pattern addresses AR6. This

conceptual pattern emphasizes the integration of in-

novation platform services (Figure 7) in a digital mar-

ketplace (Tiwana et al., 2010; Evans and Gawer,

2016). Offering innovation services (Tiwana, 2015)

focusing on the development of additional modules or

apps requires to open the RIS and supporting infras-

tructure for third-party developers by implementing

application (e.g. APIs and SDKs) and provide social

(e.g. documentation and technical support) boundary

resources (Ghazawneh and Henfridsson, 2013; Eaton

et al., 2015). External modules are developed using

technical boundary resources provided by the innova-

tion platform in the form of API services (Ghazawneh

and Henfridsson, 2013; Eaton et al., 2015).

Figure 7: Innovation Platform.

The openness of an innovation platform defines which

platform services and components from the applica-

tion and infrastructure layer can be used, modified,

and extended by third-party developers (Witte and

Zarnekow, 2018). Openness is usually defined by

the scope and richness of the interfaces offered by

the platform owner (Eisenmann, 2008). The devel-

opment environment can also be operated by the mar-

ketplace owner depending on the degree of openness

and the boundary resources provided. Third-party de-

velopers implement additional modules such as shop

themes, interfaces to other digital platforms, or fea-

ture add-ins. While innovation platforms usually ex-

ploit economies of scale and scope with increasing

efficiency and increased product variety trough re-

usability and reconfiguration of modules or services,

they may utilize further economic effects as the center

of a broader innovation ecosystem in which they may

also establish MSMs (Cusumano and Gawer, 2002;

Gawer, 2009; Buxmann and Hess, 2015). The devel-

opment process consists of, among others, processes

for developing, testing, and deploying the modules.

The integration of innovation services propels the de-

velopment to a hyper-scaling platform (Dawson et al.,

2016) Retailers increasingly establish innovation plat-

forms and provide them to other competitors to create

an integrated digital business ecosystem. One exam-

ple is REWE with its subsidiaries commercetools and

fulfillmenttools (commercetools, 2020).

Retailer’s Dual Role in Digital Marketplaces: Towards Architectural Patterns for Retail Information Systems

607

4.3 Pattern 3: Aggregated Assortment

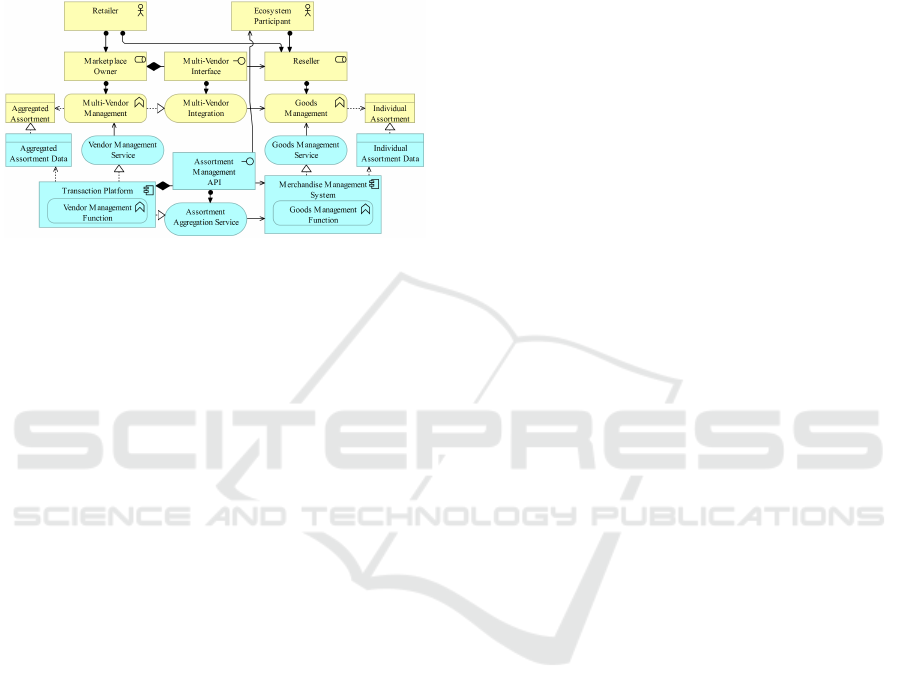

A conceptual solution for AR7 is presented in the

third exemplary architectural pattern (Figure 8). This

conceptual pattern deals with the aggregation of the

individual assortments of the different supply-side

participants (Teller and Elms, 2010).

Figure 8: Aggregated Assortment of a Digital Marketplace.

The aggregation of the assortment is managed by the

retailer in his role as marketplace owner. The market-

place owner aggregates the assortment of all supply-

side participants in reseller mode. This may also

include the retailer himself (i.e. dual role) (Hagiu,

2007). While a multi-vendor integration connects

the supply-side participants on the business layer to

the marketplace, the technical integration between

the transaction platform and the merchandise man-

agement system of the reseller is realized by the as-

sortment aggregation service on the application layer.

This service provides an assortment management API

connecting the systems of the marketplace owner and

the supply-side participants (Ghazawneh and Hen-

fridsson, 2013). For a retailer with a dual role this

means the listing of its own assortment on the mar-

ketplace. The assortment of each reseller is stored in

an individual assortment business object accounting

for possible further sales channels of the reseller. The

aggregated assortment is also captured by the market-

place owner in a business object realized by a data

object. The data objects are managed by the trans-

action platform (for the marketplace owner) and the

merchandise management system (for the reseller)

5 DISCUSSION

Within this research paper we present three exem-

plary architectural patterns pivotal for the retailer’s

dual role on digital marketplaces. They are devel-

oped based on seven ARs derived from the literature

on ecommerce in general and MSMs in particular. Al-

though there could be more than one MSM for a spe-

cific ecommerce sector (Senyo et al., 2019), winner-

takes-all-tendencies and strong network effects of in-

cumbents limit it to only one or a few (Eisenmann,

2008; McIntyre and Srinivasan, 2017). A RA or mul-

tiple architectural patterns supporting a retailer’s dual

role on digital marketplaces simplify the assessment

of RIS prior to the transition to a MSM. Hence, the

capabilities of the IS for the marketplace transforma-

tion can be assessed more accurately and may lower

the possibility for failures during the establishment

of digital marketplace. Several digital marketplaces

failed to establish successful MSMs (e.g. zapatos,

jet.com, Rakuten) either because of a small number

of participants or IS problems (Wulfert et al., 2021).

The domain-specific RA can also be used to iden-

tify potential gaps within the retailer’s RIS and reduce

the overall time to market (Angelov et al., 2012). A

retailer’s or wholesaler’s dual role on a digital mar-

ketplace results in several advantages compared to

other ecosystem participants (Figure 3). Despite pos-

sible antitrust law considerations (Bundeskartellamt,

2015), the marketplace owner will be eager to pre-

fer the offering of its own assortment to increase re-

seller revenues. As the marketplace owner controls

the touchpoint to the customer, he also has the in-

formation about fast selling and profitable articles.

This information can be used to adjust the assortment

of the reseller role mainly selling profitable articles

and leaving the long tail (McAfee and Brynjolfsson,

2017) of articles selling slowly to other ecosystem

participants. The concentration on fast selling articles

may also release storage capacity that can be offered

as additional, retail-related services to ecosystem par-

ticipants (Wulfert et al., 2021). Also With additional

sales information, the marketplace owner can calcu-

late articles for which the monetization of the match-

making (e.g. commission fees) is more profitable than

selling these articles in its reseller role. The match-

ing as core value proposition of a digital marketplace

(Armstrong, 2006; Haucap and Wenzel, 2011) relies

on proper data concerning customers, suppliers, and

articles. Thus, the data needs to be stored accessi-

bly for the matching engines to provide the customers

with desired products. The actual article is the cus-

tomer’s focus in the ecommerce environment (Hag-

berg et al., 2016) while suppliers are encapsulated by

the marketplace owners (McKinsey, 2020). Neverthe-

less, we propose to include supplier information in the

matchmaking process as customer preferences can be

matched on suppliers’ properties. Customers caring

about their environment may for example be likely

to buy articles from a supplier who can prove sus-

tainability. Integrating additional innovation services

attracts additional participants to the MSM and adds

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

608

additional value propositions. The range and scope of

modules developed by third-party developers depend

on the openness allowed by the marketplace owner

and the provided boundary resources (Ghazawneh

and Henfridsson, 2013; Eaton et al., 2015). These

modules can be related to the bridging functions en-

hancing the retail transactions between supply- and

demand-side participants (e.g. shop themes, vendor

management) or go beyond retail-centered purposes.

Amazon is a major example for the wide range of ex-

ternal modules with its Web Services stemming from

the usage of unused computational power from the re-

tail activities (Wittig et al., 2016). Hence, the mod-

eled innovation platform and development environ-

ment components are generic enough to cope with

the whole continuum of external modules. The in-

novation pattern needs to be instantiated according to

the intention of a specific marketplace owner. Digi-

tal marketplaces aggregate the assortment of several

supply-side participants and require a data model for

the articles capable of storing much unstructured data

(image, video, exploded-view drawings, spare parts

with historical data, etc.). The data model must be de-

signed flexible so that it is suitable for different prod-

uct categories agglomerating the diverse assortments

of a number of participants from independent markets

(Kollmann, 2019; Evans, 2011). This may lead to a

decoupling of the master data storage of a transaction

processing system (e.g. enterprise resource planning)

from the transaction platform and the system for prod-

uct information management. This is mainly because

not all articles or services of a MSM can be kept in

a transaction platform with all available data. While

the transaction platform requires high resolution im-

ages for digital representation in the ecommerce envi-

ronment, the enterprise resource planning systems is

mainly concerned with financial and inventory data.

However, the degree to which article data is stored

in the transaction platform and provided by an addi-

tional product information system depends on the spe-

cific environment of the retailer. The product infor-

mation system is not modeled in pattern 3 for reasons

of graphical simplification. These architectural pat-

terns from the first design iteration should be further

evaluated with practitioner insights and aggregated to

an overal RA for RIS supporting a retailer’s dual role

on digital marketplaces. Aggregating transaction and

innovation services, the digital marketplace forms an

integrated platform (Evans and Schmalensee, 2016).

The transaction platform is included in pattern 3 while

the innovation platform is part of pattern 2. An inte-

grated platform is likely to become an hyper-scaling

platform quickly achieving critical mass and shaping

industries (Dawson et al., 2016) This research paper

also has its limitations. The developed ARs are nei-

ther comprehensive nor complete. AR must also be

derived from practitioner sources (e.g. interviews, ar-

chitecture documents) in an additional relevance cy-

cle for a more sophisticated analysis. We plan to de-

rive further ARs and evaluate the seven ARs as well as

the three architectural patterns developed conducting

interviews with IT architects from retailers operating

MSMs. Although we claimed that the ARs are de-

rived from our literature analysis and make up the sole

base for the developed architectural patterns, we need

to acknowledge that the ARs are biased from our own

understanding of the meta-problem. We incorporated

our understanding of the retail-specific problem and

retailer’s dual role on digital marketplaces that leads

to interpretations with regards to the AR and architec-

tural patterns (Iivari, 2015). Moreover, the chosen en-

terprise architecture modeling language for develop-

ing the architectural patterns leads to an implicit deci-

sion for a service-oriented architecture design as this

is inherent to this language connecting actors as well

as business, application and infrastructure layers us-

ing services (Open Group, 2019). Although service-

orientation is a well-regarded paradigm, it can at least

be questioned if it is the best approach for modeling

the IS architecture of a digital marketplace with the

focus on the retailer’s dual role.

6 CONCLUSION

The main contribution of this research paper is the

determination of a retailer’s possible dual role on dig-

ital marketplaces. We derive seven ARs resulting

from a retailer’s dual role (dual role, additional partic-

ipants, affiliation, matchmaking, variety of services,

innovation services, and aggregated assortment) for

RIS. These requirements resemble a class of prob-

lems relevant for digital marketplaces in ecommerce.

Additionally, we propose three architectural patterns

(matchmaking for participants, innovation platform

services, and aggregated assortment) as a concep-

tional solution to the requirements. These architec-

tural patterns are developed literature-based and can

be applied to analyze existing RA towards the ful-

fillment of these requirements. The patterns resem-

ble buildings blocks of a meta-model as a RA for the

retail domain. Future research can test existing (sci-

entific and practice) concrete architectures and RAs

for the fulfillment of the requirements and patterns.

The architectural patterns may also be improved by

consolidating domain knowledge such as company-

specific architectures and conducting interviews with

IS architects. Another important avenue for future

Retailer’s Dual Role in Digital Marketplaces: Towards Architectural Patterns for Retail Information Systems

609

research may be an extension of the range of archi-

tectural patterns and orchestrating them to a com-

plete RA including further architecture layers. For the

demonstration and evaluation of presented and addi-

tional patterns, they can be implemented in a concrete

or experimental system as proof of concept.

REFERENCES

Abhishek, V., Jerath, K., and Zhang, Z. J. (2016). Agency

selling or reselling? Channel structures in electronic

retailing. Management Science, 62(8):2259–2280.

Angelov, S., Grefen, P., and Greefhorst, D. (2009). A clas-

sification of software reference architectures: Ana-

lyzing their success and effectiveness. In 2009 Joint

Working IEEE/IFIP Conference on Software Architec-

ture & European Conference on Software Architec-

ture, pages 141–150. IEEE.

Angelov, S., Grefen, P., and Greefhorst, D. (2012). A frame-

work for analysis and design of software reference

architectures. Information and Software Technology,

54(4):417–431.

Angelov, S., Trienekens, J. J. M., and Grefen, P. (2008).

Towards a method for the evaluation of reference ar-

chitectures: Experiences from a case. In European

Conference on Software Architecture, pages 225–240.

Springer.

APQC (2019). Amcerican Productivity & Quality Center

Process Classification Framework (PCF) - Retail PCF.

Armstrong, M. (2006). Competition in two-sided markets.

RAND Journal of Economics, 37(3):668–691.

Armstrong, M. and Wright, J. (2007). Two-sided Mar-

kets, Competitive Bottlenecks and Exclusive Con-

tracts. Economic Theory, 32(2):353–380.

Asadullah, A., Faik, I., and Kankanhalli, A. (2018). Digital

Platforms: A Review and Future Directions. In Pacific

Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS),

pages 248–262.

Aulkemeier, F., Schramm, M., Iacob, M.-E., and van

Hillegersberg, J. (2016). A Service-Oriented E-

Commerce Reference Architecture. Journal of the-

oretical and applied electronic commerce research,

11:26–45.

Baldwin, C. Y. and Clark, K. B. (2000). Design Rules: The

Power of Modularity, volume 1. MIT Press, Cam-

bridge LB - Baldwin2000.

Baldwin, C. Y. and Woodard, J. C. (2009). The architec-

ture of platforms: a unified view. In Gawer, A., editor,

Platforms, Markets and Innovation, pages 19–44. Ed-

ward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK.

Barth, K., Hartmann, M., and Schr

¨

oder, H. (2015). Be-

triebswirtschaftslehre des Handels, volume 7.,

¨

uberar.

Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden.

Bass, L., Clements, P., and Kazman, R. (2003). Software ar-

chitecture in practice. Addison-Wesley Professional,

Boston.

Becker, J. and Sch

¨

utte, R. (2004). Handelsinformation-

ssysteme : dom

¨

anenorientierte Einf

¨

uhrung in die

Wirtschaftsinformatik. Redline Wirtschaft, Frankfurt

am Main, 2., vollst edition.

Bhatti, A., Akram, H., Basit, H. M., Khan, A. U., Naqvi,

R. S. M., and Bilal, M. (2020). E-commerce trends

during COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of

Future Generation Communication and Networking,

13(2):1449–1452.

Blank, S. and Dorf, B. (2012). The startup owner’s manual:

The step-by-step guide for building a great company.

John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey.

Bundeskartellamt (2015). Digitale

¨

Okonomie - Internet-

plattformen zwischen Wettbewerbsrecht, Privatsph

¨

are

und Verbraucherschutz.

Buxmann, P. and Hess, T. (2015). Die Softwareindus-

trie:

¨

Okonomische Prinzipien, Strategien, Perspek-

tiven. Springer-Verlag.

Caillaud, B. and Jullien, B. (2003). Chicken & egg: Compe-

tition among intermediation service providers. RAND

Journal of Economics, pages 309–328.

Chen, Y. K., Chiu, F. R., and Yang, C. J. (2014). An opti-

mization model for product placement on product list-

ing pages. Advances in Operations Research, 2014.

Choudary, S. (2015). Platform Scale. How a New Breed

of Startups Is Building Large Empires with Minimum

Investment. Platform Thining Labs, New York.

Cloutier, R., Muller, G., Verma, D., Nilchiani, R., Hole,

E., and Bone, M. (2010). The concept of reference

architectures. Systems Engineering, 13(1):14–27.

commercetools (2020). L

¨

osungen f

¨

ur den digitalen Handel

von morgen.

Cusumano, M. A. and Gawer, A. (2002). The Elements

of Platform Leadership. MIT Sloan Management Re-

view, 43(3):51–58.

Dawson, A., Hirt, M., and Scanlan, J. (2016). The eco-

nomic essentials of digital strategy. A supply and de-

mand guide to digital disruption.

Dietz, M., Khan, H., and Rab, I. (2020). How do companies

create value from digital ecosystems?

Eaton, B., Elaluf-Calderwood, S., Sorensen, C., and Yoo, Y.

(2015). Distributed tuning of boundary resources: the

case of Apple’s iOS service system. MIS Quarterly:

Management Information Systems, 39(1):217–243.

Eisenmann, T. R. (2008). Managing proprietary and shared

platforms. California Management Review, 50(4):31–

53.

Evans, D. S. (2011). Platform economics: Essays on multi-

sided businesses. Competition Policy International,

Boston, Mass.

Evans, D. S. and Schmalensee, R. (2016). Matchmakers.

The New Economics of Multisided Platforms. Harvard

Business Review Press, Boston.

Evans, P. C. and Gawer, A. (2016). The rise of the platform

enterprise: a global survey.

Galster, M. (2015). Software reference architectures: re-

lated architectural concepts and challenges. In 1st In-

ternational Workshop on Exploring Component-based

Techniques for Constructing Reference Architectures

(CobRA), pages 5–8.

Galster, M. and Avgeriou, P. (2011). Empirically-grounded

reference architectures: a proposal. In Proceedings

of the joint ACM SIGSOFT conference–QoSA and

ACM SIGSOFT symposium–ISARCS on Quality of

software architectures–QoSA and architecting critical

systems–ISARCS, pages 153–158.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

610

Gawer, A. (2009). Platforms, markets and innovation - an

introduction. In Gawer, A., editor, Platforms, Mar-

kets and Innovation, pages 1–16. Edward Elgar, Chel-

tenham, UK.

Gawer, A. and Henderson, R. (2007). Platform owner en-

try and innovation in complementary markets: Evi-

dence from Intel. Journal of Economics & Manage-

ment Strategy, 16(1):1–34.

Ghazawneh, A. and Henfridsson, O. (2013). Balancing plat-

form control and external contribution in third-party

development: the boundary resources model. Infor-

mation systems journal, 23(2):173–192.

Giachetti, R. E. (2010). Design of enterprise sysetms: the-

ory, architecture, and methods. CRC Press, Boca Ra-

ton.

Gregor, S. and Hevner, A. R. (2013). Positioning and pre-

senting design science research for maximum impact.

MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems,

37(2):337–355.

Grieger, M. (2003). Electronic marketplaces: A literature

review and a call for supply chain management re-

search. European Journal of Operational Research,

144(2):280–294.

Hagberg, J., Sundstrom, M., and Egels-Zand

´

en, N. (2016).

The digitalization of retailing: an exploratory frame-

work. International Journal of Retail & Distribution

Management, 44(7):694–712.

Hagiu, A. (2007). Merchant or two-sided platform? Review

of Network Economics, 6(2).

Hagiu, A. and Wright, J. (2015). Multi-sided plat-

forms. International Journal of Industrial Organiza-

tion, 43:162–174.

Hanke, J., Hauser, M., Durr, A., and Thiesse, F. (2018).

Redefining the Offline Retail Experience : Design-

ing Product Recommendation. In Twenty-Sixth Euro-

pean Conference on Information Systems (ECIS2018),

pages 1–14, Portsmouth, UK.

H

¨

anninen, M. (2018). Has digital retail won?: The effect of

multi-sided platforms on the retail industry. Strategic

Direction, 34(3):4–6.

Haucap, J. and Heimeshoff, U. (2018). Ordnungspoli-

tik in der digitalen Welt: Ordnungsdefizite und

L

¨

osungsans

¨

atze. In Thieme, J. and Haucap, J., edi-

tors, Wirtschaftspolitik im Wandel: Ordnungsdefizite

und L

¨

osungsans

¨

atzeSchriften zu Ordnungsfragen der

Wirtschaft 105. De Gruyter, Oldenburg.

Haucap, J. and Wenzel, T. (2011). Wettbewerb im Inter-

net: Was ist online anders als offline? Zeitschrift f

¨

ur

Wirtschaftspolitik, 60(2):200–211.

Hein, A., Schreieck, M., Wiesche, M., and Krcmar,

H. (2016). Multiple-Case Analysis on Governance

Mechanisms of Multi-Sided Platforms. In Nissen, V.,

Stelzer, D., Straßburger, S., and Fischer, D., editors,

Multikonferenz Wirtschaftsinformatik (MKWI) 2016,

pages 1613–1624, Ilmenau.

Heinrich, L. and Stelzer, D. (2009). Informationsmanage-

ment: Grundlagen, Aufgaben, Methoden. Oldenbourg

Wissenschaftsverlag, M

¨

unchen.

Hevner, A. and Chatterjee, S. (2010). Design Research in

Information Systems, volume 22 of Integrated Series

in Information Systems. Springer, New York [u.a.].

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., and Ram, S.

(2004). Design science in information systems re-

search. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Sys-

tems, 28(1):75–105.

Iivari, J. (2003). The IS Core - VII: Towards Information

Systems as a Science of Meta-Artifacts. Communi-

cations of the Association for Information Systems,

12:568–581.

Iivari, J. (2015). Distinguishing and contrasting two strate-

gies for design science research. European Journal of

Information Systems, 24(1):107–115.

Ivarsson, F. and Svahn, F. (2020). Digital and Conven-

tional Matchmaking – Similarities, Differences and

Tensions. In Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii Interna-

tional Conference on System Sciences (HICCS 2020),

pages 5932–5941, Hawaii.

Kawa, A. and Wałe¸siak, M. (2019). Marketplace as a

key actor in e-commerce value networks. Logforum,

15(4):521–529.

Kollmann, T. (2019). E-Business. Grundlagen elektronis-

cher Gesch

´

Eaftsprozesse in der Digitalen Wirtschaft.

Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden, 7.,

¨

uberar edition.

Kotler, P. and Keller, K. L. (2016). Marketing Management.

Pearson, Boston [u.a.], 16 edition.

Laudon, K. C. and Traver, C. G. (2019). E-Commerce 2018:

business. technology. society, volume 14. Pearson Ed-

ucation, Boston.

Levy, M., Weitz, B. A., and Grewal, D. (2019). Retail-

ing management. McGraw-Hill Education, New York,

NY, tenth edit edition.

Li, Q., Wang, Q., and Song, P. (2019). The Effects of

Agency Selling on Reselling on Hybrid Retail Plat-

forms. International Journal of Electronic Commerce,

23(4):524–556.

Li, Z. and Penard, T. (2014). The role of quantitative and

qualitative network effects in B2B platform competi-

tion. Managerial and Decision Economics, 35(1):1–

19.

March, S. T. and Smith, G. F. (1995). Design and natural

science research on information technology. Decision

Support Systems, 15(4):251–266.

McAfee, A. and Brynjolfsson, E. (2017). Machine, Plat-

form, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future. W W

Norton & Co Inc, New York City LB - Mcafee2017.

McIntyre, D. P. and Srinivasan, A. (2017). Networks, plat-

forms, and strategy: Emerging views and next steps.

Strategic Management Journal, 38(1):141–160.

McKinsey (2020). The conflicted Continent: Ten charts

show how COVID-19 is affecting consumers in Eu-

rope.

Moazed, A. and Johnson, L. N. (2016). Modern Monop-

olies. What It Takes to Dominate the 21st-Century

Economy. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

M

¨

uller-Hagedorn, L., Toporowski, W., and Zielke, S.

(2012). Der Handel : Grundlagen - Management

- Strategien. Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, 2.,

vollst edition.

Nakagawa, E. Y., Oliveira Antonino, P., and Becker, M.

(2011). Reference architecture and product line ar-

chitecture: A subtle but critical difference. In Pro-

ceedings of the 5th European Conference on Software

Retailer’s Dual Role in Digital Marketplaces: Towards Architectural Patterns for Retail Information Systems

611

Architecture (ECSA 2011), volume LNCS 6903, pages

207–211, Essen, Deutschland.

Nicola, M., Alsafi, Z., Sohrabi, C., Kerwan, A., Al-Jabir,

A., Iosifidis, C., Agha, M., and Agha, R. (2020). The

socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pan-

demic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal

of Surgery, 78(1):185–193.

OMG (2019). ARTS Business Process Model for Retail.

Open Group (2019). ArchiMate 3.1 Specification.

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M. A., and Chat-

terjee, S. (2007). A design science research method-

ology for information systems research. Journal of

management information systems, 24(3):45–77.

Reillier, L. C. and Reillier, B. (2017). Platform Strategy.

How to Unlock the Power of Communities and Net-

works to Grow Your Business. Routledge, London.

Rochet, J. and Tirole, J. (2003). Platform competition in

two-sided markets. Journal of the European Eco-

nomic Association, 1(4):990–1029.

Rochet, J. and Tirole, J. (2006). Two-sided markets: a

progress report. The RAND journal of economics,

37(3):645–667.

Rotar, A. (2020). eCommerce Report 2020.

Rudolph, T., Nagengast, L., Melanie, B., and Bouteiller,

D. (2015). Die Nutzung mobiler Shopping Apps im

Kaufprozess. Marketing Review St. Gallen, 3(32):42–

49.

Sch

¨

utte, R. (2017). Information systems for retail compa-

nies. In Dubois, E. and Pohl, K., editors, International

Conference on Advanced Information Systems Engi-

neering, pages 13–25, Essen, Deutschland. Springer.

Sch

¨

utte, R. (2018). Retailing in Zeiten der Digitalisierung.

Die Plattformen dominieren den Wettbewerb. IM+io

Best & Next Practices aus Digitalisierung — Manage-

ment — Wissenschaft, Heft 4:46–51.

Sch

¨

utte, R. and Vetter, T. (2016). Analyse des Digi-

talisierungspotentials von Handelsunternehmen. In

Gl

¨

aß, R. and Leukert, B., editors, Handel 4.0: Die

Digitalisierung des Handels-Strategien, Technolo-

gien, Transformation, pages 75–112. Springer Gabler,

Berlin [u.a.].

Senyo, P. K., Liu, K., and Effah, J. (2019). Digital business

ecosystem: Literature review and a framework for fu-

ture research. International Journal of Information

Management, 47(January):52–64.

Shapiro, C. and Varian, H. R. L. B. S. (1998). Informa-

tion rules: a strategic guide to the network economy.

Harvard Business Press, Boston, Mass.

Shaw, M. and Garlan, D. (1996). Software Architecture.

Perspectives on an Emerging Discipline. Prentice-

Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Staykova, K. S. and Damsgaard, J. (2015). A Typology of

Multi-sided Platforms: The Core and the Periphery.

In ECIS 2015 Proceedings, volume Paper 174.

T

¨

auscher, K. and Laudien, S. (2018). Understanding

platform business models: A mixed methods study

of marketplaces. European Management Journal,

36(3):319–329.

Taylor, R. N., Medvidovic, N., and Dashofy, E. M. (2010).

Software Architecture. Foundations, Theory and Prac-

tice. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, USA.

Teller, C. and Elms, J. (2010). Managing the attractiveness

of evolved and created retail agglomerations formats.

Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 28(1):25–45.

Tiwana, A. (2015). Evolutionary Competition in Plat-

form Ecosystems. Information Systems Research,

26(2):266–281.

Tiwana, A., Konsynski, B., and Bush, A. A. (2010). Plat-

form Evolution: Coevolution of Platform Architec-

ture, governance, and Environmental Dynamics. In-

formation Systems Research, 21(4):675–687.

Turban, E., Whiteside, J., King, D., and Outland, J.

(2017). Introduction to Electronic Commerce and So-

cial Commerce. Springer Texts in Business and Eco-

nomics. Springer International Publishing, Cham, 4

edition.

Vaishnavi, V., Kuechler, B., and Petter, S. (2019). DE-

SIGN SCIENCE RESEARCH IN INFORMATION

SYSTEMS.

Van Aken, J. E. (2004). Management Research Based

on the Paradigm of the Design Sciences: The Quest

for Field-Tested and Grounded Technological Rules.

Journal of Management Studies, 41(2):219–246.

Van Alstyne, M., Parker, G., and Choudary, S. P. (2016).

6 Reasons Platforms Fail. Havard Business Review,

31(6).

Wang, S. and Archer, N. P. (2007). Electronic market-

place definition and classification: literature review

and clarifications. Enterprise Information Systems,

1(1):89–112.

West, J. (2003). How open is open enough? Melding pro-

prietary and open source platform strategies. Research

policy, 32:1259–1285.

Willcocks, L. P., Feeny, D., and Islei, G. (1997). Man-

aging information technology as a strategic resource.

McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The Economic Institutions of

Capitalism. Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting.

The Free Press/MacMillan, New York [u.a.].

Winter, R. and Fischer, R. (2006). Essential layers, arti-

facts, and dependencies of enterprise architecture. In

10th IEEE International Enterprise Distributed Ob-

ject Computing Conference Workshops (EDOCW’06),

pages 640–647. IEEE.

Witte, A. and Zarnekow, R. (2018). Is Open Always

Better? - A Taxonomy-based Analysis of Platform

Ecosystems for Fitness Trackers. In Multikonferenz

Wirtschaftsinformatik, pages 732–742, L

¨

uneburg.

Wittig, M., Wittig, A., and Whaley, B. (2016). Amazon web

services in action. Manning, Shelter Island, NY.

Wulfert, T., Seufert, S., and Leyens, C. (2021). Develop-

ing Multi-Sided Markets in Dynamic Electronic Com-

merce Ecosystems - Towards a Taxonomy of Digi-

tal Marketplaces. In Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii

International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS

2021), pages 1–10, Maui, Hawaii.

ICEIS 2021 - 23rd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

612