Raising Awareness of Students’ Self-Directed Learning Readiness

(SDLR)

Sanna Laine

a

, Mikko Myllym

¨

aki

b

and Ismo Hakala

c

University of Jyv

¨

askyl

¨

a, Kokkola University Consortium Chydenius, P.O. Box 567, FI-67701, Kokkola, Finland

Keywords:

Self-Directed Learning (SDLR), SDLR Scale, Distance Education, Online Learning, Lifelong Learning,

Adult Learning, Information Technology.

Abstract:

This paper describes the mapping of self-directed learning readiness (SDLR) for adult students applying for

a master’s degree program delivered entirely as distanced learning. Since SDLR is strongly linked to both

adult learning and online education, developing of self-directed learning (SDL) skills should be taken into

consideration in our degree program. Making future students aware of SDLR is the first stage in introducing

self-directed learning methods and practices in learning environments. The easiest way to do this is to have

students answer an SDLR self-assessment questionnaire and give them feedback regarding their SDLR level.

This paper presents how this is realized and provides the preliminary results of the study and the applicants’

SDLR score distributions. The results indicate high SDLR among all applicants.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowles (Knowles, 1975) defined self-directed learn-

ing (SDL) as “a process in which an individual

takes the initiative, with or without the help of oth-

ers, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating

and implementing appropriate learning strategies and

evaluating learning outcomes.” This is perhaps the

most widely accepted definition of SDL. Self-directed

learning readiness (SDLR) comprises personality

characteristics that define an individual’s degree of

self-management, desire to learn, and self-control

(Fisher et al., 2001). We live in a rapidly chang-

ing society, and to maintain professional skills, self-

directed lifelong learning is a necessity (Guglielmino,

2013). As Knowles (Knowles, 1975) expressed, “We

must think of learning as being the same as living.”

He argued that learners with initiative learn more and

better than passive “reactive” learners. Self-directed

learners have greater motivation and tend to retain

and make use of what they learn. Knowles consid-

ered SDL to be part of the natural process of human

psychological development.

Adapting the definition by Knowles, Guglielmino

and Guglielmino (Guglielmino and Guglielmino,

2001) defined SDL as “a process in which the learner

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7165-9687

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0263-0917

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0048-3212

is responsible for identifying what is to be learned,

when it is to be learned and how it is to be learned.

The learner is also responsible for evaluating not only

if the learning occurs but if it is relevant to the ob-

jective.” When developing her self-directed learning

readiness scale (SDLRS) using the Delphi technique,

Guglielmino (Guglielmino, 1978) connected a highly

self-directed learner with qualities like initiative, in-

dependence, persistence, self-discipline, curiosity, re-

sponsibility, self-confidence, strong desire for learn-

ing, goal-orientation, and organizing skills.

Since SDL may also bring about many abili-

ties supporting studying, such as increased retention,

greater interest in continued learning, greater inter-

est in the subject, more positive attitudes toward the

instructor, and enhanced self-concept (Brockett and

Hiemstra, 1991), the benefits of SDL are hard to deny.

Fortunately, there is evidence that SDLR can be de-

veloped. Knowing their own SDLR levels may arouse

students’ interest in enhancing their SDL skills. Thus,

this research will promote the growth of students’

awareness of SDLR. In addition, the distribution of

students’ SDLRS scores may convince education or-

ganizers and lecturers to take SDLR theory into ac-

count when arranging and planning instruction.

In this preliminary stage of the study, we identi-

fied a way to realize SDLR evaluation in an online

environment. We also examined the SDLRS score

distributions of first-year students and student appli-

Laine, S., Myllymäki, M. and Hakala, I.

Raising Awareness of Students’ Self-Directed Learning Readiness (SDLR).

DOI: 10.5220/0010403304390446

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2021) - Volume 1, pages 439-446

ISBN: 978-989-758-502-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

439

cants. The future goal is to observe possible changes

in adult students’ SDLR levels in a master’s program

delivered as distance learning and to find a means of

developing SDL skills in online environments. In the

long run, collecting applicants’ SDLRS scores may

also enable the detection of whether their SDLR lev-

els will affect their ability to be accepted into the pro-

gram and commit to it. The SDLR survey by Fisher,

King, and Tague (Fisher et al., 2001) was integrated

into the virtual learning environment. Students were

given materials that explained the purpose of the sur-

vey and provided information on how SDLR could be

developed in connection with the education program.

Responding to the survey constituted part of the first

compulsory course for new students, which addresses

academic study practices and skills.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 in-

troduces SDL in more detail and connects it to our

students. Section 3 discusses the related work. Sec-

tion 4 explains how the SDLR scale is realized in our

learning platform. The results and their meaning are

discussed in section 5. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2 SELF-DIRECTED LEARNING

The introduction already provided some definitions

for SDL. In this section, SDL is explored through

SDL models. In addition, the relationship between

SDL and online/distance learning and adult educa-

tion, as well as the ways to measure SDLR levels, will

be considered.

2.1 Self-Directed Learning Models

Garrison’s (Garrison, 1997) model includes three

overlapping SDLR dimensions: motivation, self-

management, and self-monitoring. Garrison defines

self-directed learning as “an approach where learn-

ers are motivated to assume personal responsibil-

ity and collaborative control of the cognitive (self-

monitoring) and contextual (self-management) pro-

cesses in constructing and confirming a meaning-

ful and worthwhile learning outcome.” Motivation is

a key factor in initiating and maintaining learning

processes. Garrison classifies motivation into two

terms: entering motivation and task motivation. “En-

tering motivation establishes commitment to a par-

ticular goal and the intent to act. Task motivation

is the tendency to focus on and persist in learn-

ing activities and goals” (Garrison, 1997). Regard-

ing Garrison’s three over-lapping dimensions, self-

management focuses on external activities associated

with the learning process and considers functions for

achieving learning goals and learning resource man-

agement. Self-monitoring refers to the “responsibil-

ity to construct meaning.” This includes developing

new knowledge and reconciling new information with

previous knowledge. Self-monitoring ensures that the

learning goals are being met.

Brockett and Hiemstra (Brockett and Hiemstra,

1991) introduced the Personal Responsibility Ori-

entation (PRO) model. It separates SDL into two

dimensions: instructional transaction characteris-

tic (teaching-learning process) and a learner‘s per-

sonal characteristics. The dimensions are guided

by personal responsibility, which works as a start-

ing point and is influenced by social context. To

clarify some confusion, the model was aroused dur-

ing years and was updated and reconfigured into the

Person-Process-Context (PPC) Model (Hiemstra and

Brockett, 2012)in order to disengage themselves from

the political tone that the term “personal responsibil-

ity” may have obtained. Person (or a learner’s per-

sonal characteristics in the PRO model) refers to one’s

characteristics, such as their “creativity, critical re-

flection, enthusiasm, life experience, life satisfaction,

motivation, previous education, resilience, and self-

concept”. Process (or instructional transaction char-

acteristic in the PRO model) refers to one’s “facilita-

tion, learning skills, learning styles, planning, orga-

nizing, and evaluating abilities, teaching styles, and

technological skills.” Adding the Context element to

the model separates the model from many other SDL

definitions. Context takes into account “the envi-

ronmental and sociopolitical climate, such as culture,

power, learning environment, finances, gender, learn-

ing climate, organizational policies, political milieu,

race, and sexual orientation”. Learning activities can-

not be separated from the social context in which they

occur (Brockett and Hiemstra, 1991).

2.2 SDL in the Online and Adult

Learning Context

As an educator, it is important to understand how on-

line learning affects SDLR and how SDL should be

taken into account when arranging education for adult

students, most of whom already have at least one pre-

vious degree and several years of work experience.

The interest in SDL in relation to distance learning

emerged from the structural constraints of distance

education and the independence that distance learn-

ers have (Garrison, 2003). Already in the 80s, Moore

(Moore, 1986) studied the implications of SDL for

distance education and recommended that staff be

trained to emphasize SDL in their courses and prepare

material to be delivered in a personalized way based

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

440

on students’ needs and interests. SDLR shares mul-

tiple features with the requirements of distance learn-

ing.

Song and Hill (Song and Hill, 2007) studied the

role of SDL in online learning contexts. They pointed

out that initial SDL models were developed when

face-to-face instruction was the predominant mode of

higher education. Thus, they formed a conceptual

model to understand SDL in an online context. In the

model, the “learning context” indicates the impact of

environmental factors on SDL. This learning context

includes “design” elements, like resources, structure,

and nature of the learning tasks, and “support” ele-

ments, which refer to the instructor’s feedback and

peer collaboration. Song and Hill (Song and Hill,

2007) brought out the opportunities and challenges

that an online context introduces. They deduced that

online learning is closely associated with SDL. To

succeed in online learning, many SDL-related skills

are needed, such as planning one’s learning pace,

monitoring learning comprehension, and exploring

and using various learning resources effectively. Stu-

dents need to be highly motivated as the online con-

text may provide more opportunities to procrastinate

studies, as online classes often do not provide strict

schedules. In addition, students are more responsible

for monitoring their own learning in online environ-

ments.

Barak et al. (Barak et al., 2016) suggested that

online students were more aware of mastery learn-

ing and information processing strategies than their

on-campus peers. In addition, online students indi-

cated better planning, control, and evaluation skills

for their learning process. Information resource man-

agement is an important part of SDL skills. Tang and

Tseng (Tang and Tseng, 2013) discovered that dis-

tance learners who have higher self-efficacy for infor-

mation seeking and proficiency in information manip-

ulation exhibited higher self-efficacy for online learn-

ing.

Loizzo et al. (Loizzo et al., 2017) studied learn-

ers’ motivations for enrolling in a massive open on-

line course (MOOC), their perceptions of success and

completion, and the barriers encountered while trying

to complete the MOOC from an SDL perspective. In

Loizzo et al.’s study, SDL theory was utilized to better

understand how adult learners experience MOOCs.

According to their survey responses, the students had

SDL-related features, like an awareness of their learn-

ing purposes, processes, and goals within the MOOC

course. However, Loizzo et al. (Loizzo et al., 2017)

stated that MOOC courses often do not provide the

opportunity for learners to assess their own progress

in relation to their personal goals.

Rashid and Asghar (Rashid and Asghar, 2016)

studied the relationship between technology use and

academic performance, student engagement, and self-

directed learning. Technology use was assessed with

a ”media and technology usage and attitudes” scale.

Only the questions measuring media and technology

usage, such as internet, social media, smartphone,

and media sharing usage, were included in the re-

search. They found that the use of technology has a

directly positive relationship with self-directed learn-

ing. The same study also showed a positive correla-

tion between SDL and student engagement.

The online environment also creates possibilities

to enhance SDL skills. Kim et al. (Kim et al., 2014)

developed a self-directed learning system to guide

students to self-manage their own learning processes.

The system enabled students to customize content by

setting specific learning goals by reflecting on their

learning experiences, self-monitoring activities and

performances, and collaboration with other students.

The system was found to improve students’ overall

competency scores in being self-directive by practic-

ing and reinforcing their SDL abilities.

SDLR is often related to lifelong learning, and

Knowles’ work has had a great impact on this real-

ization. In addition to SDL, Knowles was a special-

ist of andragogy (the study of adult learning). He

defined the assumptions about the characteristics of

learners by saying that “as individuals mature, their

self-concept moves from one of being a dependent

personality toward being a self-directed human be-

ing” (Knowles, 1980). However, age may not directly

predict SDLR levels. For example, Heo and Han (Heo

and Han, 2018) found no correlation between age and

SDLR within their adult online college student. Thus,

the link between adulthood and SDLR is based more

on “maturity” than age. Knowles also argued that

adults have “a deep psychological need to be gener-

ally self-directing, although they may be dependent

in particular temporary situations” (Knowles, 1980).

This means that teacher-centered education may not

satisfy adult students.

Applying SDL in formal education is a challeng-

ing task. A strict curriculum may hinder the fa-

cilitation of SDL, and applying SDL may require

extra effort from teachers. According Guglielmino

(Guglielmino, 2013), possible reasons for not adopt-

ing SDL are the tendency to teach as one was taught,

the ease of assigning a grade based primarily on quan-

titative evaluation, school and teacher ratings based

on testing, increasing class sizes that make it more

difficult to use authentic assessment methods, and,

for higher education faculty, a lack of instruction in

teaching strategies.

Raising Awareness of Students’ Self-Directed Learning Readiness (SDLR)

441

2.3 SDLR Scales

The most widely used SDLR assessment tool is

Guglielmino’s (Guglielmino, 1978) SDLRS. This is

a self-report questionnaire that consists of 58 Likert-

type items drawn up with the help of experts using

the Delphi technique. The expert group consisted of

14 authorities in the area of SDL. Among the ex-

perts were Malcolm Knowles and Allen Tough, both

major contributors in the field of adult education.

Guglielmino’s model defined eight SDL components:

openness to learning opportunities, self-concept as an

effective learner, initiative and independence in learn-

ing, informed acceptance of responsibility for one’s

own learning, love of learning, creativity, positive ori-

entation to the future, and ability to use basic study

skills, and problem-solving skills.

Guglielmino’s SDLRS only measures the degree

to which a person perceives themselves as reflecting

the skills and attitudes related to SDLR. However,

like Brockett and Hiemstra (Brockett and Hiemstra,

1991) point out, there is evidence that SDLRS scores

correlate with actual behavior. This correlation was

found by Hassan (Hassan, 1981) when she examined

the connection of SDLRS scores with the number of

learning projects. The learning projects used in the re-

search were planned to fulfill the definition of Tough’s

(Tough, 1979) definition.

In this research Fisher’s SDLRS is used (Fisher

and King, 2010). Fisher’s scale was developed to

correct issues regarding the validity and reliability of

Guglielmino’s scale and to make it available at no

cost. Originally, it was planned for nursing students,

but during the principal component analysis of the

scale, all questions relating to nursing were removed.

The remaining items were comparatively generally

applicable. Fisher’s SDLRS has three subscales: de-

sire for learning, self-management, and self-control.

Fisher et al. (Fisher et al., 2001) did not define these

subscales in great detail, but they resulted from an

inter-correlation analysis between Likert-type items.

The desire for learning (DL) subscale includes ques-

tions relating to one’s motivation and attitudes to-

ward studying. The self-management (SM) subscale

includes questions associated with a person’s devel-

opment of appropriate external conditions and skills

for the learning process, such as time management

and resource handling. The self-control (SC) sub-

scale includes questions about a person’s ability to

set goals and evaluate their own learning. The sub-

scales have clear points of overlap with Garrison’s

(Garrison, 1997) SDLR dimensions: motivation, self-

management, and self-monitoring.

Fisher’s SDLRS includes 40 5-point Likert-type

items: 13 items for self-management, 12 for desire

for learning, and 15 for self-control. The possible to-

tal scores can range between 40 and 200. When the

SDLRS was originally tested with a sample of 201

students enrolling for a Bachelor of Nursing program

at the University of Sydney, Australia, the total scores

were normally distributed with a mean of 150.55 (me-

dian 150). Thus, Fisher et al. (Fisher et al., 2001) used

a total score of greater than 150 to indicate SDLR.

Later, Fisher and King (Fisher and King, 2010) re-

evaluated the factor structure of the SDLR subscales,

and found that the data collected from 227 first-year

undergraduate nursing students did not fit the speci-

fied factor model until 11 items were removed; how-

ever, they recommended that all 40 items should be

used until the results could be confirmed with a larger

sample.

3 RELATED WORK

Most of the students who participated in this research

had an engineering background before applying for

the Mathematical Information Technology master’s

degree program. Fisher’s scale was used, when Stew-

art (Stewart, 2007) mapped final year engineering stu-

dents’ SDLRS scores as a part of the process to inte-

grate project-based learning, as a major component of

the institution’s learning and teaching options. Based

on the data gathered, the average total score of the 26

students was 158.8. Sumuer (Sumuer, 2018) collected

SDLRS scores for 153 undergraduate students in the

School of Education at a public university in Turkey,

identifying the extent to which their SDLR affected

their technology SDL (i.e. their use of internet and

communication technology (ICT) for learning experi-

ences that enable individuals to take control of plan-

ning, implementing, and evaluating their own learn-

ing). The average item score was 3.97 (SD = 0.44),

making the total mean score also 158.8. The study

also found a medium, positive, significant correlation

between SDLR and SDL with technology.

Although the SDLR items in Fisher’s scale do not

include any factors specifically relating to nursing, it

is still mainly used to evaluate health care students.

In fact, nursing students have been the most exten-

sively studied group for SDLR long before Fisher’s

scale was developed (Brockett and Hiemstra, 1991).

Therefore, we also compared our students to medi-

cal students. Abraham et al. (Abraham et al., 2011)

explored the SDLR of first-year undergraduate med-

ical students in physiology and searched for possible

correlations with academic performance. The aver-

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

442

age total score of the students was 151.4, and 60.2%

of students had a score greater than 150. The highest

mean item score was for questions measuring desire

for learning (3.91), followed by self-control (3.87),

and then self-management (3.44). Based on their

academic performance during the first-year program,

students were divided into high achievers (n = 10),

medium achievers (n = 41), and low achievers (n =

79). High achievers had the highest score for all

three SDLR subscales, and statistical significance was

found for self-control.

Deyo et al. (Deyo et al., 2011) studied the effect of

SDLR and academic performance on SDL activities

and the resources used to prepare for an abilities’ lab-

oratory course. The mean SDLRS score was 148.6 for

153 university students participating in a pharmacy

course. The median was 149, and 68 students (44%)

scored over 150. Similarly, Atwa (Atwa, 2018) col-

lected SDLRS scores for second-year undergraduate

medical students and examined the relationship be-

tween their scores and the students’ grade point av-

erages (GPAs) and gender. The mean SDLRS score

for the 239 students was 159.25. Atwa found a statis-

tically significant, positive correlation between GPA

and SDLR. Furthermore, the SDLRS scores were also

found to be significantly higher for females.

More engineering students’ SDLR results can be

found from studies using Guglielmino’s SDLR scale.

The scores for Guglielmino’s SDLRS varies between

58 and 290, with values between 202 and 226 indi-

cating an average level of SDLR (Guglielmino and

Guglielmino, 2013). Litzinger et al. (Litzinger et al.,

2005) tested undergraduate engineering students us-

ing Guglielmino’s SDLRS. They found that, for first-

year students, the mean score was 215 (n = 80), which

fell into the average category. Guglielmino’s SDLRs

was also applied by Jiusto et al.’s (Jiusto and DiB-

iasio, 2006) study, wherein the effects of an expe-

riential academic engineering program that empha-

sized lifelong learning and SDL skills were examined.

The scores were collected before and after a 14-week

project. The project experience had a modest positive

effect on students’ SDLRS scores, as the mean score

increased from 219.4 to 222.7, but eventually fell into

the average category.

4 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES AND

DATA COLLECTION

The master’s degree students in Mathematical Infor-

mation Technology at Kokkola University Consor-

tium Chydenius are mainly working adults who study

alongside their work. For this reason, their educa-

tion has been strongly distance-learning-based with

the use of educational technologies (Hakala and Myl-

lym

¨

aki, 2016). Thus, the students’ studies can be tai-

lored to their personal schedules and life situations.

In such an educational environment, SDL is of great

importance for the progress of learning. Therefore,

it is meaningful to examine the students’ SDLR lev-

els. It may even be reasonable to expect that students

who gravitate towards distance education have higher

SDLR scores.

The purpose of this research paper is to identify

how we have implemented SDLR evaluation in an on-

line environment. In this research, we also examine

the SDLRS score distributions of student applicants

and compare the results with other similar surveys. It

is hoped that research related to self-direction will in-

crease students’ awareness of their own SDLR since,

when they become aware of it, they can try to develop

it. The broader objective of future research related

to self-direction is to examine how SDL skills could

be developed in an online environment and how to

determine whether there will be any changes in the

SDLR of the master’s degree students during their

studies. One aim of future research is to discover

whether there are any differences in SDLR between

students admitted to the degree program and those not

selected.

4.1 Implementation of an SDLR

Questionnaire

Students responded to the Fisher’s SDLR survey at

the beginning their studies in the Mathematical In-

formation Technology program. The survey will be

offered them again during graduation. The SDLRS

scores are collected during application process. The

enrollment process includes an introductory course

that applicants must complete to be admitted. The

function of the introductory course is to give stu-

dents some idea of the requirements for studying in

this education program in terms of combining their

study habits with their life situations and balancing

the course workload. In the spring of 2020, there were

two introductory courses: Communication Protocols

and Introduction to Embedded Systems. The SDLR

survey was one of the exercises for the courses.

The survey was completed at the beginning of the

introductory course; therefore, it was also answered

by students who, for various reasons, dropped out of

the course and were not admitted to the degree pro-

gram. When the survey was first introduced, it was

also sent to first year students. The second time the

students will complete the SDLR survey is when they

attend a master’s thesis seminar in the final stages of

Raising Awareness of Students’ Self-Directed Learning Readiness (SDLR)

443

their studies.

The survey was delivered as part of a student’s

profile in the electronic system used for the degree

program. Students use the same system to watch, for

example, video learning material; hence, it is con-

stantly in active use by the students. Other surveys,

such as a learning style survey, have also been in-

tegrated into this system in the past (Hakala et al.,

2016). The system automatically identifies the re-

sponding student and stores the student’s responses

with the appropriate identification information in a

database. For this study, the scale was translated into

Finnish and four items were negatively phrased. The

items were offered in five, eight-item clusters, and

mixed in such a way that each cluster included two

or three items for each dimension.

4.2 Feedback given to Students

After completing the SDLR survey, the students were

shown a results page where they saw their own re-

sults and the average of the results for all students

in the degree program. If a graduating student has

completed the survey also at the beginning of stud-

ies, the results will be shown for both first and lat-

est sets of answers. Along with their own results, the

students were given some feedback and information

about the SDLR in general. In their SDLRS, Fisher et

al. (Fisher et al., 2001) concentrated on developing a

statistically valid and internally consistent evaluation

tool but did not consider how to give feedback to the

students. Our solution was to provide, alongside the

SDLRS score, a freely translated version of interpre-

tations for Guglielmino’s SDLRS (Guglielmino and

Guglielmino, 2013) scores. The SDLRS score result

is either high, average, or low, indicating the preferred

ratio of self-directed and structured learning.

In addition, the definition and benefits of SDLR,

as well as some methods to enhance it, were sum-

marized. For students who wanted to familiarize

themselves with the subject in more detail, selected

articles were linked to the results site. For exam-

ple, Guglielminos’ paper entitled “Becoming a more

self-directed learner” (Guglielmino and Guglielmino,

2004) provides direct guidance to learners.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

At this first stage of research, 34 applicants completed

the SDLR questionnaire, 8 women and 26 men. The

mean of the scores was 165.0, with a range of 65. The

women’s average score was slightly higher than the

men’s (167.3 vs. 164.3), but the difference was not

statistically significant with this data. Twenty-eight

students (82%) scored over 150 (the SDLR bound-

ary). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for self-control,

self-management, and desire for learning were 0.83,

0.88, and 0.64, respectively, indicating the scales’

good internal consistency and reliability. The distri-

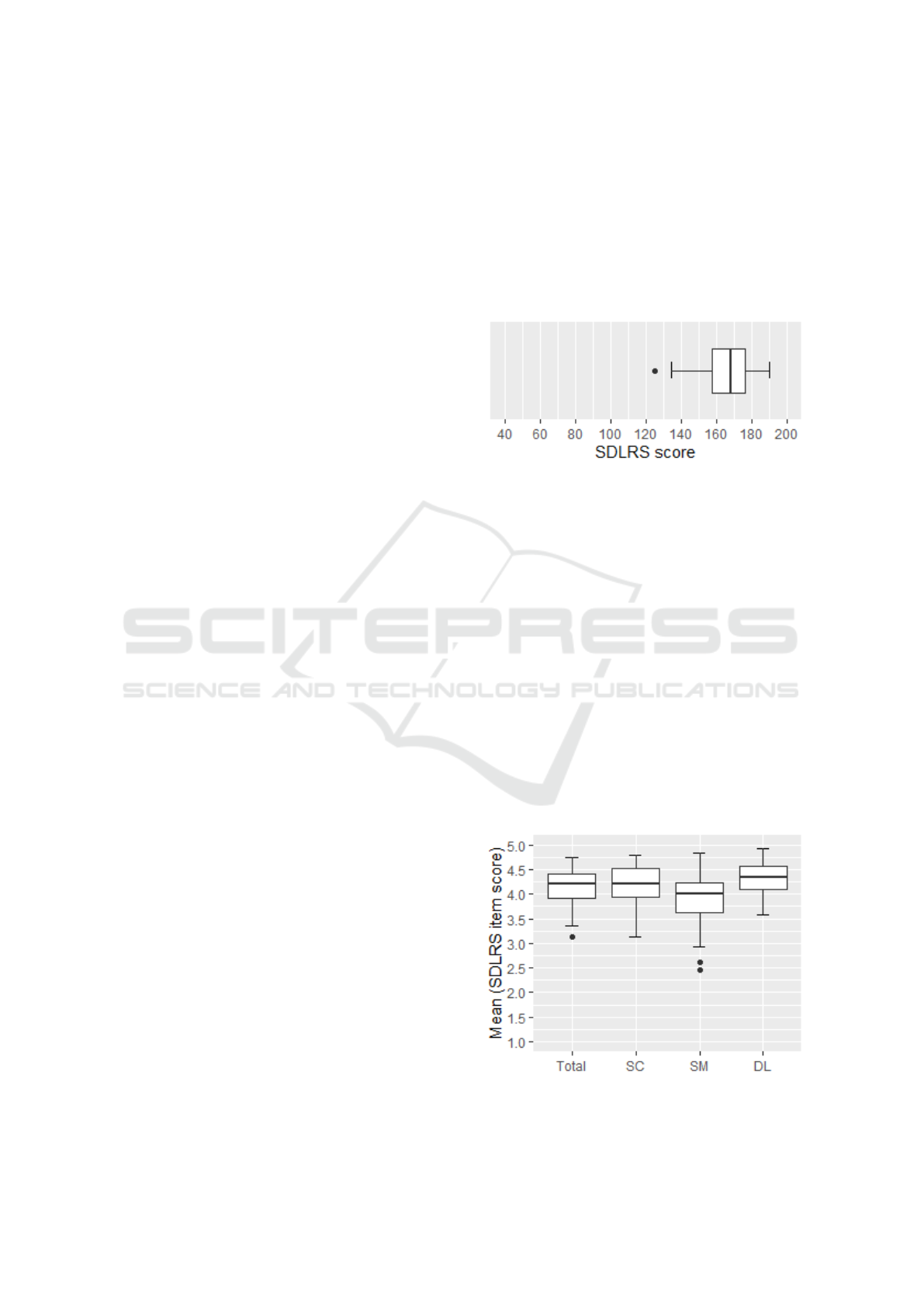

bution of scores is depicted as a boxplot in Fig. 1.

The median was 168, and the upper and lower quar-

tiles were 157.0 and 176.3, respectively.

Figure 1: The distribution of students’ SDLRS scores (The

outlier in the boxplot is an observation that is further than

1.5 times the width of the box from the lower quartile.).

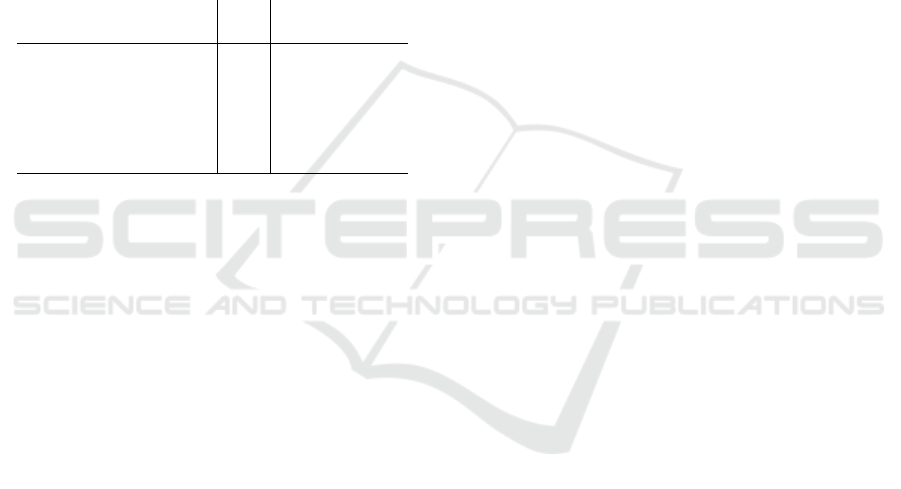

Since the SDLRS includes an uneven number of

items for each subscale, the comparison of dimen-

sions explored students’ average item scores for each

dimension. The average of the Likert scale items mea-

suring self-control, self-management, and desire for

learning were 4.2, 3.9, and 4.3, respectively (Fig. 2).

A high desire to learn is a logical result among our

students, and a desire to learn informs us of motiva-

tion; adult students who chose to study while working

are expected to possess this trait.

Compared to related studies (see Table 1), the ap-

plicants in this study were highly self-directed, while

the order of dimension means (desire of learning

highest and self-management lowest) was common

in many studies. The high SDLR levels of our stu-

dents may have risen from their greater maturity, fol-

Figure 2: The boxplot of students’ mean SDLRS item

scores in total, and for each SDLR dimension: self-control

(SC), self-management (SM), and desire for learning (DL).

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

444

lowed by age, previous degrees and work experience,

and family experiences. We can also assume that ap-

plicants have a desire to participate in an education

program conducted entirely through distance learning

and found this studying practice suitable for them-

selves. Since SDL has a great role in distance learn-

ing (Song and Hill, 2007), it may well be that this

education program attracts more self-directed people.

In addition, distance learning and ICT programs natu-

rally involve the use of technology, which was found

to have a positive relationship with SDL (Rashid and

Asghar, 2016). From an education organizer perspec-

tive, the results are, if not expected, at least very pos-

itive.

Table 1: Means of the SDLRS scores presented in the re-

lated work of this research.

Source N

Mean of the

SDLRS scores

This research 34 165.0

(Atwa, 2018) 239 159.25

(Stewart, 2007) 26 158.8

(Sumuer, 2018) 153 158.8

(Abraham et al., 2011) 130 151.4

(Deyo et al., 2011) 153 148.6

Due to the high SDLRS scores, we can expect the

applicants to have high expectations for the program

regarding their ability to apply SDLR to their stud-

ies. In our program, students have some control over

the pace of learning at which they proceed. The fact

that all education is delivered online gives students the

freedom and responsibility to set their own weekly

schedules. Some courses allow totally independent

learning while others establish loose deadlines to en-

courage students to proceed at the pace of live teach-

ing, while giving enough leeway to accommodate per-

sonal study preferences. Although the flexibility of

the program was developed to alleviate adult students’

time management challenges, it can also foster SDLR.

To employ adult students’ prior knowledge and serve

their interests, students are given more control over

course content. Greater emphasis on the delivery of

courses is placed on large exercises, such as essays,

group work, coding projects, or laboratory assign-

ments, which allows students to freely choose the tar-

get of application. Efforts are also made to enable

students to share the information they possess with

each other, using peer reviews, student presentations,

group work, and collaboration tools on the learning

platform. To develop our education program in the

future, we will add some elements to the online envi-

ronment that reinforce students’ SDL skills. Proven

methods can be found from the work of Kim et al.

(Kim et al., 2014).

6 CONCLUSION

Self-direction plays an emphasized role in online

learning environments. The current global situation

of the pandemic has created an even greater need to

transfer information online. For this reason, research

related to self-direction is very topical. This study

examined student applicants’ SDLRS score mapping

in the Mathematical Information Technology mas-

ter’s degree program at Kokkola University Consor-

tium Chydenius and depicted the integration of the

SDLR scale into a learning management system. Dis-

tance learning and adult education are fundamental el-

ements of the degree program, and SDL is strongly

connected to both. Thus, SDL should not be dis-

missed while organizing education. This preliminary

research showed that applicants answered the SDLR

questionnaire readily and that their scores were rel-

atively high, indicating that they were already self-

directed at the beginning of the education program.

This makes education organizers responsible for cre-

ating a meaningful learning environment that fulfills

students’ expectations. In the future, more students

will be included in the study to ensure the high SDLR

of program applicants. If some applicants fail to be

admitted or decide to discontinue their studies, their

SDLRS scores will be compared to admitted students’

results. Similarly, the change in SDLRS results will

be further monitored, and scores can even be com-

pared with study performance. A comparison will

also be made between adult students in different dis-

ciplines in our institution, and between younger, gen-

eral upper secondary school, students.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research for this paper was financially supported

by the European Social Fund, grant no. S21124, with-

out which the present study could not have been com-

pleted. The authors wish to thank the Central Finland

Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the

Environment for their help.

REFERENCES

Abraham, R. R., Fisher, M., Kamath, A., Izzati, T. A.,

Nabila, S., and Atikah, N. N. (2011). Exploring first-

year undergraduate medical students’ self-directed

learning readiness to physiology. Advances in Physi-

ology Education, 35(4):393–395.

Atwa, H. S. (2018). Assessment of medical students’ readi-

ness for self-directed learning. Egyptian Journal of

Community Medicine, 36(1).

Raising Awareness of Students’ Self-Directed Learning Readiness (SDLR)

445

Barak, M., Hussein-Farraj, R., and Dori, Y. J. (2016).

On-campus or online: examining self-regulation and

cognitive transfer skills in different learning settings.

International Journal of Educational Technology in

Higher Education, 13(1):1–18.

Brockett, R. G. and Hiemstra, R. (1991). Self-direction in

adult learning: Perspectives on theory, research, and

practice. Routledge.

Deyo, Z. M., Huynh, D., Rochester, C., Sturpe, D. A., and

Kiser, K. (2011). Readiness for self-directed learning

and academic performance in an abilities laboratory

course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Educa-

tion, 75(2).

Fisher, M., King, J., and Tague, G. (2001). Development

of a self-directed learning readiness scale for nursing

education. Nurse education today, 21(7):516–525.

Fisher, M. J. and King, J. (2010). The self-directed learn-

ing readiness scale for nursing education revisited: A

confirmatory factor analysis. Nurse education today,

30(1):44–48.

Garrison, D. R. (1997). Self-directed learning: Toward

a comprehensive model. Adult education quarterly,

48(1):18–33.

Garrison, D. R. (2003). Self-directed learning and distance

education. Handbook of distance education, pages

161–168.

Guglielmino, L. M. (1978). Development of the self-

directed learning readiness scale. PhD thesis, Pro-

Quest Information & Learning.

Guglielmino, L. M. (2013). The case for promoting self-

directed learning in formal educational institutions.

SA-eDUC, 10(2).

Guglielmino, L. M. and Guglielmino, P. J. (2001). Mov-

ing toward a distributed learning model based on

self-managed learning. S.A.M.Advanced Management

Journal, 66(3).

Guglielmino, L. M. and Guglielmino, P. J. (2004). Becom-

ing a more self-directed learner. Getting the most from

online learning: A learner’s guide, pages 25–38.

Guglielmino, L. M. and Guglielmino, P. J. (2013). Learning

preference assessment. www.lpasdlrs.com. accessed

3.3.2020.

Hakala, I., H

¨

arm

¨

anmaa, T., and Laine, S. (2016). Learn-

ing styles module as a part of a virtual campus. In

2016 IEEE Global Engineering Education Confer-

ence (EDUCON), pages 425–433.

Hakala, I. and Myllym

¨

aki, M. (2016). From face-to-face to

blended learning using ict. In 2016 IEEE Global En-

gineering Education Conference (EDUCON), pages

409–418.

Hassan, A. M. (1981). An investigation of the learning

projects among adults of high and low readiness for

self-direction in learning. PhD thesis, Iowa State Uni-

versity.

Heo, J. and Han, S. (2018). Effects of motivation, academic

stress and age in predicting self-directed learning

readiness (sdlr): Focused on online college students.

Education and Information Technologies, 23(1):61–

71.

Hiemstra, R. and Brockett, R. G. (2012). Reframing the

meaning of self-directed learning: An updated model.

In Adult Education Research Conference.

Jiusto, S. and DiBiasio, D. (2006). Experiential learning

environments: Do they prepare our students to be self-

directed, life-long learners? Journal of Engineering

Education, 95(3):195–204.

Kim, R., Olfman, L., Ryan, T., and Eryilmaz, E. (2014).

Leveraging a personalized system to improve self-

directed learning in online educational environments.

Computers & Education, 70:150–160.

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-Directed Learning: A Guide

for Learners and Teachers. Association Press, New

York, NY, USA.

Knowles, M. S. (1980). The Modern Practice of Adult Ed-

ucation: From Pedagogy to Andragogy: Revised and

Updates. Cambridge Adult Education, Prentice Hall

Regents.

Litzinger, T. A., Wise, J. C., and Lee, S. H. (2005). Self-

directed learning readiness among engineering under-

graduate students. Journal of Engineering Education,

94(2):215–221.

Loizzo, J., Ertmer, P. A., Watson, W. R., and Watson, S. L.

(2017). Adult mooc learners as self-directed: Percep-

tions of motivation, success, and completion. Online

Learning, 21(2).

Moore, M. (1986). Self-directed learning and distance ed-

ucation. International Journal of E-Learning & Dis-

tance Education/Revue internationale du e-learning et

la formation

`

a distance, 1(1):7–24.

Rashid, T. and Asghar, H. M. (2016). Technology use, self-

directed learning, student engagement and academic

performance: Examining the interrelations. Comput-

ers in Human Behavior, 63:604–612.

Song, L. and Hill, J. R. (2007). A conceptual model for

understanding self-directed learning in online envi-

ronments. Journal of Interactive Online Learning,

6(1):27–42.

Stewart, R. A. (2007). Investigating the link between self

directed learning readiness and project-based learning

outcomes: the case of international masters students in

an engineering management course. European Jour-

nal of Engineering Education, 32(4):453–465.

Sumuer, E. (2018). Factors related to college students’ self-

directed learning with technology. Australasian Jour-

nal of Educational Technology, 34(4).

Tang, Y. and Tseng, H. W. (2013). Distance learners’ self-

efficacy and information literacy skills. The journal of

academic librarianship, 39(6):517–521.

Tough, A. (1979). The adult’s learning projects: A fresh

approach to theory and practice in adult learning (2nd

ed.). Learning Concepts.

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

446