Will I Continue Online Teaching? Language Teachers’ Experience

during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Ching Ting Tany Kwee

School of Education, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, The University of New South Wales, Australia

Keywords: Remote Learning, Distant Learning, Online Learning, Self-efficacy, Outcome Expectations, Language

Teachers, Social Cognitive Career Theory, Interpretative Phenomenological Approach.

Abstract: Due to public health concerns, many K-12 schools were closed and switched to remote learning during the

COVID-19 pandemic. Since language learning emphasises interaction, this brings a discussion on its

effectiveness and feasibility of online teaching beyond the pandemic. This study aims to explore language

teachers’ online teaching experiences in the pandemics and outline factors influencing their choices on future

online teaching. Adopting the Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) and Interpretative Phenomenological

Analysis (IPA), the researcher interviewed five language teachers internationally and examined their lived

experience in this qualitative research. Participants indicated that a positive learning environment and greater

well-being of teachers favoured them to continue online teaching while their doubt on students’ learning

outcomes impeded them from future use. These findings can be predictors of the teachers’ choices on online

learning and useful in devising measures or professional development courses to foster a sustainable online

learning development beyond the pandemic.

1 INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has also brought great

impact to K-12 schools globally (Asanov et al., 2021;

Iivari et al., 2020; UN, 2020; Vial, 2019). On 11

March 2020, The World Health Organisation (WHO)

declared COVID-19 as a pandemic (UN 2020). Due

to public health concerns, school closure is a popular

strategy in many countries which have a relatively

serious outbreak, for instance, India, Brazil, Ecuador,

Algeria, China and Hong Kong (UN 2020). Over 94%

of the students, i.e. 1.58 billion students, had to transit

to remote learning, requiring teachers to conduct

online lessons in various means to ensure learning

continuity (Asanov et al., 2021; UN, 2020).

Generally, teleconferencing tools like Googlemeet

and Zoom classroom are used for live sessions, and

Google Classroom is also used to check students’

daily works (Iivari et al., 2020; UN, 2020). There are

also some private companies developing platforms,

including whiteboard and other add-on functions for

online learning (Manegre & Sabiri, 2020). With both

the advantages and disadvantages of online learning,

a further discussion is drawn on whether online

teaching can become a ‘new normal’ in the post-

pandemic era (Asanov et al., 2021; Blizak et al., 2020;

Iivari et al., 2020; Manegre & Sabiri, 2020; UN,

2020).

1.1 Purpose of the Study

This study aims at investigating the significant factors

influencing language teachers’ choices on continuing

or leaving online teaching in the post-pandemic era.

Through examining language teachers’ online

teaching experiences during the COVID-19

pandemic, it scaffolds the personal and contextual

factors which can be predictors of their future choice

of behaviours (Brown & Lent, 2019; Lent & Brown,

1996, 2006; Lent, 2004).

Based on the purpose of the study, the researcher

proposed the following research questions:

1. How do language teachers describe their

online teaching experience?

2. Why do language teachers desire to continue

online teaching in the post-pandemic era?

3. Why do language teachers desire to stop

online teaching in the post-pandemic era?

1.2 Significance of the Study

This study is unique in examining language teachers’

Kwee, C.

Will I Continue Online Teaching? Language Teachers’ Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

DOI: 10.5220/0010396600230034

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2021) - Volume 2, pages 23-34

ISBN: 978-989-758-502-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

23

online teaching experience holistically with the lens

of SCCT. It provides a holistic view of how language

teachers’ interests and choices of online learning

develops. It also outlines the interrelationship

between personal and contextual factors which

influence language teachers’ development of future e-

learning choices (Brown & Lent, 2019; Lent &

Brown, 1996, 2006; Lent, 2004). Second, the findings

of this research are significant as it provides insights

for education policy-makers and the school

management developing measures to adopt and

facilitate online learning and to attain sustainability

and equity.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Research studies (Asanov et al., 2021; Blizak et al.,

2020; Dos Santos, 2019; Garrison & Cleveland-

Innes, 2005; Iivari et al., 2020; Manegre & Sabiri,

2020; Ogange et al., 2018; Rovai, 2007; Terrell,

2005) were done on examining the impacts, benefits

and drawbacks on online learning or distant learning.

The following section first summarises the current

research findings in relation to both online and

language teaching. Then the research gaps are

identified to posit this study.

Languages have always perceived to be a subject

which needs communication and interaction (Hyland,

2007; Skehan, 2003). With features like social media,

forums and chats, scholars (Blizak et al., 2020; Luis

M. Dos Santos, 2019; Hyland, 2007; Manegre &

Sabiri, 2020; Skehan, 2003) suggested that online

learning is beneficial as a student-centred and

interaction-oriented learning delivery in an authentic

context connected to their real lives to express

meaning without pressure. Some scholars (Blizak et

al., 2020; Coulter et al., 2007; Ellis, 2000; Garrison &

Cleveland-Innes, 2005; Hyland, 2007; Skehan, 2003)

also suggested that those interactive tasks and timely

feedback are essential in language learning to offer

learners opportunities to process and use the

information in a higher cognitive and critical manner

by challenging students on valued discourse and bring

reflection and understanding on values, beliefs and

cultures. These technological features fostered

flexibility and enhanced students’ performance at a

faster rate, particularly on learning colloquial

language (Dos Santos, 2019; Jurkovič, 2019;

Manegre & Sabiri, 2020). Such advantages not only

benefit ordinary students, but also students in remote

areas who are with limited access to educational

resources to achieve social equity (Jurkovič, 2019;

Manegre & Sabiri, 2020; Rovai, 2007). Besides, with

the mastery of technological skills and familiarity of

online environments among teachers and students,

teachers experimented with some digital solutions to

the continuity of learning during the COVID-19

pandemic (Blizak et al., 2020; Iivari et al., 2020).

Moreover, remote learning also promotes an

opportunity for collaborative teaching as teachers can

team up to share the workload (Iivari et al., 2020).

With the advantages mentioned above, some teachers

perceived optimistically on the possibility of distance

learning in some teaching periods in future due to

their successful experiences during the COVID-19

pandemic (Basilaia & Kvavadze, 2020; Blizak et al.,

2020; Iivari et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, with more than 80% of the course

content is delivered online and typically no face-to-

face meetings, students suggested that online learning

limit their time to communicate with their teachers

(Blizak et al., 2020; Stodel & Thompson, 2006).

Some studies (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005;

Stodel & Thompson, 2006) also suggested that

teachers expressed worries on students’ meaningful

engagement in class due to their physical absence.

Scholars (Acton & Glasgow, 2015; Hastings &

Bham, 2003; Hebert & Worthy, 2001; Iivari et al.,

2020; MacIntyre et al., 2020) also identified that

stress created by increasing workload, difficulties in

assessment and the abrupt transition to online

teaching could be detrimental to teachers’ mental

health. Another concern is that teachers are not

prepared to adapt to new teaching methodologies and

receive little training on the online delivery mode

(MacIntyre et al., 2020; UN, 2020). While social

equity and quality education are under the limelight

as one of the stated sustainable development goals by

the United Nations, students who are from a lower

socio-economic background who have less access to

the internet are less likely to attend classes and do

their homework (Asanov et al., 2021; Sachs et al.,

2019; UN, 2020).

Previous studies (Asanov et al., 2021; Blizak et

al., 2020; Dos Santos, 2019; Garrison & Cleveland-

innes, 2005; Iivari et al., 2020; MacIntyre et al., 2020;

Manegre & Sabiri, 2020; Ogange et al., 2018; Rovai,

2007; Terrell, 2005) indicated there were both

advantages and disadvantages of implementing

online learning through an examination of the

effectiveness of teaching and learning. Very few of

the studies (Iivari et al., 2020; MacIntyre et al., 2020)

examined teachers’ teaching experiences in relation

to online teaching. One of the shortcomings of

focussing on effectiveness is that it reduces choices to

behaviours and may fail to recognise the sense-

making process (Slezak, 1991; Talbot, 1982). Such

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

24

reduction can be useful in generating methods to

reach desirable outcomes such as stimulus control

(Slezak, 1991; Talbot, 1982). However, successful

teaching incorporates a variety of variables, including

teachers’ beliefs, classroom setting, social cultures

and appropriate pedagogies (Cantrell et al., 2003;

Placer & Dodds, 1988). These factors can act together

to influence teachers’ motivations, attitudes and

behaviours (Hackett & Byars, 1996; Lent & Brown,

1996, 2008; Lent, 2004). Therefore, the mental

process of language teachers making decisions on

online teaching, which is overlooked in previous

studies, should be taken into consideration.

3 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) is chosen as

the theoretical framework in this study. Gaining

inspiration from Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory

(Bandura, 1986), researchers developed the SCCT to

specifically focus on how academic and career choice

develop and persist through examining the triadic

causal relationship between self-efficacy, behaviours

and choices (Brown & Lent, 2019; Lent & Brown,

1996, 2006; Lent, 2004). Since language teachers’

choices on teaching tools and teaching methods

comprise a myriad of personal and contextual factors

(Blizak et al., 2020; Cantrell et al., 2003; Iivari et al.,

2020; Placer & Dodds, 1988), a few benefits can be

achieved by adopting the SCCT as a theoretical

framework.

First, the SCCT underscores the dynamic

interplay between individual, environmental and

behavioural variables to draw a more precise

representation on the decision-making process of

adopting online teaching (Brown & Lent, 2019; Lent

& Brown, 1996; Lent, 2004). Researchers (Powazny

& Kauffeld, 2020; Sparks & Pole, 2019) also praised

its power on outlining a more accurate and holistic

cognitive and psychological mechanism in relation to

personal factors, social supports and barriers. Second,

the interrelation between the SCCT variables self-

efficacy, outcome expectations and goals allowed

researchers to look into how career interest develops

and turns into actions (Lent, 1994; Lent & Brown,

1996). It allows researchers to examine specific

beliefs influencing teaching pedagogies and teaching

outcomes (Cadenas et al., 2020; Cosnnolly et al.,

2018). Third, the SCCT stresses individuals as an

active agency for changes (Bandura, 1986, 1997; Lent

& Brown, 1996; Lent, 2004). Such transformative

and predictive power of self-efficacy, affirmed by

substantial empirical evidence (Capri et al., 2017;

Dos Santos, 2019b; Fouad et al., 2008; Pham et al.,

2019; Wang, 2013), enables the different

stakeholders to devise intervention strategies to orient

teachers’ choices and preferences on online teaching

in future.

4 METHODOLOGY

The Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA)

is selected as the methodology as the researcher

would like to look into the language teachers’ online

teaching experience instead of producing objective

statements about the teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs

and performance outcomes in a distant learning

environment (Alase, 2017; Pringle et al., 2011; Smith,

2004, 2015; Smith & Osborn, 2008). IPA gives full

appreciation to individuals’ account and allows an in-

depth analysis and richness of every single participant

by making sense of their personal and social world

without distortions (Pringle et al., 2011; Smith, 2004;

Smith & Osborn, 2008). This allows the researcher to

examine how their personal and contextual factors

influence their perception of self-efficacy and

performance outcome through their lived stories

(Lent et al., 2003; Lent & Brown, 1996; Smith, 2004;

Smith & Osborn, 2008).

4.1 Participants

According to the IPA handbook and other scholars

(Alase, 2017; Creswell, 2007, 2012; Pringle et al.,

2011; Smith, 2004, 2015; Smith & Osborn, 2008), a

smaller sample size, with five to six participants

recommended, can allow for a richer depth of analysis

from the original meanings of the participants and ‘go

beyond’ the apparent content. To ensure the research

study to shed light on a broader context, a fairly

homogenous sample to whom the research questions

were significant was found through purposive

sampling (Alase, 2017; Bernard, 2006; Etikan, 2016;

Patton, 2002; Pringle et al., 2011; J. A. Smith &

Osborn, 2008). As a result, five participants from

different countries were selected through purposive

sampling. These participants had similar lived

experience, which was online teaching during the

COVID-19 pandemic (Alase, 2017; Creswell, 2007,

2012; J. A. Smith & Osborn, 2008).

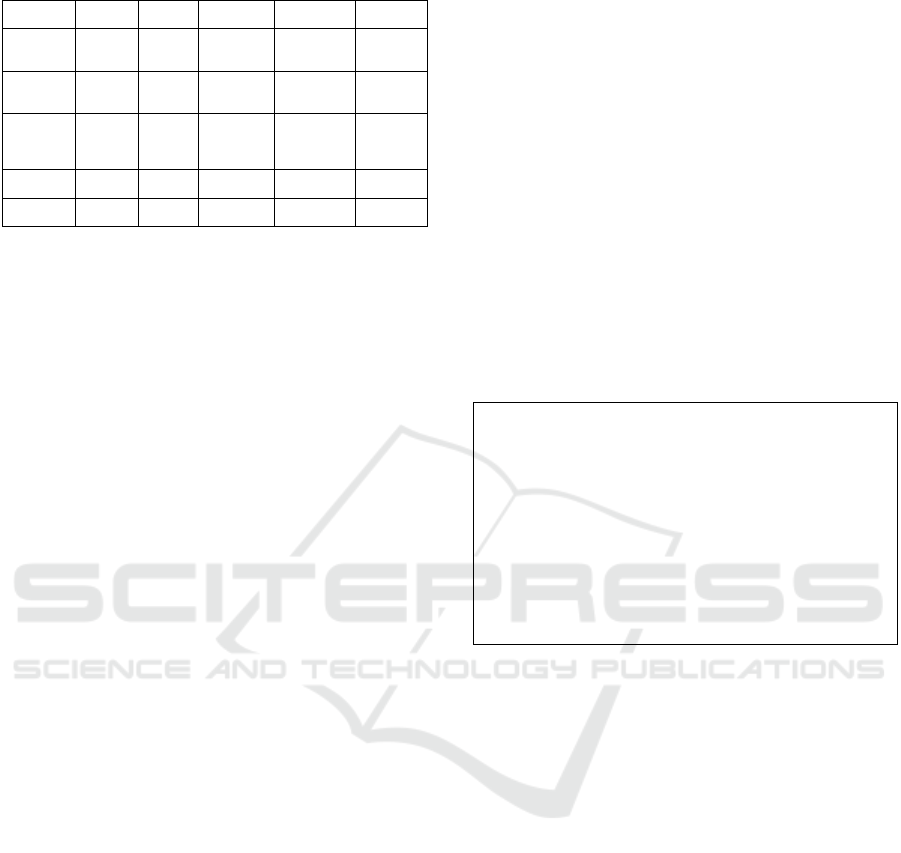

Based on the guidelines of the IPA on qualitative

research studies, detailed demography of participants

is listed in Table 1 for an understanding of the

participants’ background (Alase, 2017; Creswell,

2007, 2012; Pringle et al., 2011; Smith, 2004, 2015;

Smith & Osborn, 2008).

Will I Continue Online Teaching? Language Teachers’ Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic

25

Table 1: Brief demography of the participants.

Name Gender Age Subject

taught

Yeas of

experience

Campus

Location

Melina F Mid-

30s

English,

Literature

in English

8 Australia

Sam M Early-

40s

Chinese,

Chinese

Literature

10+ Hong

Kong

Catherine F Mid-

20s

English,

English

Literature,

ESL

3 Canada

Jason M Mid-

40s

Chinese,

ESL

10+ New

Zealand

Natalie F Late-

30s

ESL 2 Russia

Since the participants are all in-service teachers,

the researcher used pseudonyms to protect their

identities from their current and further employers in

the field (Creswell, 2007, 2012; Merriam, 2009).

4.2 Data Collection and Analysis

Two online one-on-one interview sessions were done

(Seidman, 2013). Each individual interview lasted

75-90 minutes. The first interview was to establish

rapport and empathy with the participants (Patton,

2002; Smith & Osborn, 2008; Welch & Patton, 1992).

It focussed on language teachers’ personal

backgrounds, lived experiences and previous

traditional and online teaching experiences in their

countries (Alase, 2017; Smith et al., 2005; Smith &

Osborn, 2008). The second interview focussed on

their current online teaching experiences. Through

semi-structured interviews with open-ended

interview questions, the participants can not only

narrate their online teaching experience during the

COVID-19 pandemic, but the researcher can also

follow the participants’ interests and concerns for

more in-depth discussion (Alase, 2017; Smith et al.,

2005; Smith & Osborn, 2008). Guided by the SCCT,

the interview questions aim to explore language

teachers’ personal variables (e.g. health, language,

race and family) and contextual variables (e.g.

classroom management, teaching support and

learning environment) in relation to their teaching

experiences (Brown & Lent, 2019; Lent 2004, Lent &

Brown, 1996, 2006).

All the conversations were recorded and

transcribed (Creswell, 2007, 2012). The transcripts

were then sent to the participants to gain approval to

process the data information (Creswell, 2007, 2012).

To ensure the validity of the collected data,

triangulation was employed, including observations

of recorded lessons and teaching materials (Creswell,

2007, 2012).

After data collection, a general inductive

approach was employed to first, identify the first-

level themes by open-coding techniques with the

concepts from the grounded theory (Creswell, 2007,

2012; Thomas, 2006). Then axial coding was used to

categorise the open-coding results to generate

second-level themes (Merriam, 2009; Moustakas,

1994; Patton, 2002). During the data analysis, three

themes and six subthemes emerged.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To answer the research questions, the researcher

categorised the findings into three themes and six

subthemes. Transcribed quotations from participants

are inserted to substantiate the findings. The major

themes and subthemes are listed in Table 2.

Table 2: Themes and Subthemes.

1. Positive learning environment: Reasons for continuing online

teaching

1.1 Great power from teachers

1.2 Greater students’ engagement

2. Better well-being: Reasons for continuing online teaching

2.1 Work efficiency

2.2 Work-life balance

3. Uncertain teaching performance: Reasons for stopping online

teaching

3.1 Evaluation of students’ learning outcomes

3.2 Difficulties in implementing formative assessment

5.1 Positive Learning Environment:

Reasons for Continuing Online

Teaching

Previous studies (Dos Santos, 2019; Garrison &

Cleveland-innes, 2005; Manegre & Sabiri, 2020)

showed that online learning creates mixed influences

on students’ learning due to its positive impact on

facilitating discussion and negative impact on

capturing students’ attention. In this study, it showed

students’ concentration problem does not have a

significant relationship with online learning (Lent &

Brown, 1996; Nauta & Epperson, 2003). Instead, this

study showed that online platforms offer a variety of

tools to ensure students on track and engage in the

lessons. The positive learning environment fostered

by online learning influences language teachers’ self-

efficacy beliefs positively (Bandura, 1997; Lent &

Brown, 1996, 2008; Robert & Brown, 2013). The

successful online teaching experiences constitute

experiences of prior accomplishments and become a

strong predictor of future accomplishment, resulting

in a decision of continuing online teaching among

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

26

language teachers (Lent & Brown, 1996, 2008;

Robert & Brown, 2013)

.

5.1.1 Greater Power from Teachers

Previous studies (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005,

2010; Stodel & Thompson, 2006) showed that

teachers expressed worries on students’ attention and

concentration due to their physical absence in online

learning. This study found that there is no significant

relationship between students’ attention span and

their learning outcomes (Lent & Brown, 1996; Lent

et al., 2003). One said,

“Good students are always good. Mischievous

students are always mischievous. It’s not related

to online or traditional teaching… If they want to

learn, they learn no matter it is online or face-to-

face.” (Sam, Hong Kong)

Some participants shared similar views. For

example, another participant, Jason, said,

“It is not about whether they [students] can focus

during the whole online session. It’s about

whether they want to focus... In classrooms

students can also be distracted if they are bored.

They can be daydreaming…You can’t really

tell…” (Jason, New Zealand)

However, online platforms offer some functions,

which serve as an indicator of how actively students

participate in lessons (Dos Santos, 2019; Jurkovič,

2019; Manegre & Sabiri, 2020). Previous studies

(Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005) suggested that

these technologies allow teachers to have more power

to control their lessons. This study affirms that

language teachers found such tools are effective

means to keep students on tasks. One said,

“Zoom has got an attention tracker and video

recording function. It’s good… I remind my

students that the app can track and record their

performance... Another app ClassIn allows

students to collaborate to write a text. You can see

real-time what they are writing… That’s the

evidence proving they’re working…” (Melina,

Australia)

Previous studies suggested that teachers’ greater

leadership role can facilitate discussions better

(Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005). This study

affirmed such finding as participants suggested that

online platforms’ instant video and audio sharing

functions can ensure students’ engagement (Dos

Santos, 2019; Jurkovič, 2019). These features grant

teachers to have greater administrative power to

enforce classroom discipline and foster a better

environment for class discussions. One participant

shared his view on students’ positive learning

attitude. One said,

“I asked my students to switch on their webcams.

Then I can make sure that they sit still. This can

ensure they are engaging in the class…This is the

respect they should pay to the speaker.” (Sam,

Hong Kong)

Another participant, Natasha, reinforced such

finding that features like muting participants in

teleconferencing platform could create a better

learning environment. She said,

“Sometimes in classrooms, students tend to have

silly arguments or off-track discussions. In Zoom

It seems I can manage them better. While I am

giving my instructions, I can mute all the

participants to ensure them are in a quiet

environment and… focus on my teaching. I

unmuted all participants for Q&A or discussion

time.” (Natalie, Russia)

Reflected on the previous studies (Garrison &

Cleveland-Innes, 2005), this study affirmed that

online learning platforms offer video recording,

tracking and text collaboration functions to allow

greater control power for language teachers.

According to the SCCT, teachers’ job satisfaction and

professional identity can be boosted due to better

classroom management (Lent & Brown, 1996, 2008;

Lent et al., 2003). The findings of this study aligned

with such hypothesis. Due to a surge in job

satisfaction, language teachers are more likely to

continue using online learning platforms (Lent &

Brown, 1996, 2008; Lent et al., 2003).

5.1.2 Greater Student Engagement

Previous studies (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005;

Grant & Lee, 2014) suggested that interaction is a

cornerstone of educational experience, and

technologies provide great possibilities in

communications. Educators enjoy a more democratic

approach in teaching, and this can engage students to

develop a higher-order and more critical discussions

without pressure (Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005;

Grant & Lee, 2014). The findings in this study

affirmed with the previous studies (Blizak et al.,

2020; Ellis, 2004; Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005)

that online learning can build a community of higher-

cognitive inquiries. One said,

“I changed a bit of the class structure. Before [the

pandemic], I did the reading with students in-

class… English is not their first language. They

didn’t want to read aloud. They were afraid of

making mistakes… Now I can assign the reading

as pre-task…They do it at home. I put more mini-

Will I Continue Online Teaching? Language Teachers’ Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic

27

discussions in the lessons… Students like it…They

feel more free to share and talk. They are not

afraid that they will be judged because of

mispronunciation. I’m so proud of them… they

volunteered some great ideas…” (Natalie,

Russia)

The findings suggested such community is built

due to a better lesson structure in online platform.

With a better structure, students feel more

comfortable to input information to construct

knowledge. A successful language learning

experience emphasises on getting one’s meaning

across and convey information (Canale & Swain,

1980; Skehan, 2003). This study also showed that

some other features in other online teaching platforms

also fosters a positive learning environment by

enacting positive reinforcement and giving rewards to

actively-participated students (Lent & Brown, 1996,

2008; Lent et al., 2003). One said:

“ClassIn [an online teaching platform] has a

feature giving trophies…I awarded each student a

trophy when they completed a task or answered a

question… Younger students are excited with

that… They like the animation and sound effects

when they were awarded with trophies. They

asked for more.” (Melina, Australia)

In a favourable learning environment, students

can develop confidence from positive experience,

which serves as a motivation in further language

acquisition (Peirce, 1995). This study showed that

online learning enabled students to engage in the

lessons more actively and language teachers utilised

the lesson structure and in-app features to attain their

teaching goals. As a result, more effective

communications, which is an important learning

outcome of language education, creates a positive

learning environment (Hyland, 2007; Skehan, 2003).

According to the SCCT, a more favourable contextual

environment makes language teacher perceive their

experiences positively (Lent & Brown, 1996, 2008;

Lent et al., 2003). Reflected in their positive

affections and confidence, it can be seen that such

successful experiences boost their self-efficacy, and

they can expect a similarly successful teaching

outcome in the future (Lent & Brown, 1996, 2008;

Lent et al., 2003). As a result, they are more willing

to continue their online teaching in future.

5.2 Better Well-being: Reasons for

Continuing Online Teaching

Previous studies (Hebert & Worthy, 2001; Iivari et

al., 2020; MacIntyre et al., 2020) suggested that an

increase of challenging workloads and a blurred line

between home and work could lead to frustration

among teachers. This study showed another

perspective that language teachers found online

teaching lessened their workload and boosted their

work efficiency. Besides, language teachers could

also benefit from working from home to obtain a

work-life balance. With insights from the SCCT, the

researcher concluded that online teaching can boost

language teachers’ well-being as they can manage

their life, time and teaching more efficiently (Lent &

Brown, 1996, 2008; Lent, 2004). The higher work

efficiency and attainment of both work and personal

goals foster language teachers’ positive outcome

expectations on personal and job satisfaction to

decide on continuing online teaching (Bandura, 1986,

1997; Lent & Brown, 1996, 2008; Lent, 2004).

5.2.1 Work Efficiency

Previous studies (Iivari et al., 2020; MacIntyre et al.,

2020) indicated that teachers’ work efficiency was

negatively affected due to the extra time needed to

prepare for lessons and personalised assignments in

distant learning. However, in this study, the

researcher found that online teaching brings a surge

in work efficiency, which is one of their reasons for

continuing using online teaching. On the other hand,

this study affirmed some of the previous findings

(Blizak et al., 2020; Iivari et al., 2020) that online

teachings can boost their work efficiency with a

mastery of technologies and utilisation of teaching

time. Participants agreed that online teaching boosted

their working efficiency as more time could be spent

on teaching-related activities. One said,

“I use Google Classroom to collect and return

their homework…No hassle… I haven’t been that

efficient during my 20 years of teaching career.

I’m superb in marking students’ writing.… I can

mark seven pieces of Secondary Six writing, five

pieces of Secondary Five writing and integrated

tasks for each form…” (Sam, Hong Kong)

Another participant also advocated with a similar

view:

“In the online lesson, I can instantly access their

classwork and give feedback. I don’t have to mark

them after the lessons… Once I switch off the

camera, I can send the annotated notes back to

students…It’s fast.” (Melina, Australia)

Previous literature (Acton & Glasgow, 2015;

Hastings & Bham, 2003) indicated that teachers with

greater well-being would think positively about the

demands of the job and a sense of professional

competence. They attained happiness when they

achieve their pedagogic goals (Acton & Glasgow,

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

28

2015). Aligned with the SCCT hypothesis (Lent &

Brown, 1996, 2008; Lent et al., 2005), this study

showed that online teaching yields language teachers’

job satisfaction as working from home provides goal-

relevant supports. Such positive affections from the

progress and successful attainment of the work goals

foster a self-aiding effect on future choice on online

teaching (Acton & Glasgow, 2015; Lent et al., 1994,

2005; Lent & Brown, 2008).

Apart from greater engagement in teaching-

related activities, many participants also expressed

that minimising the time on teaching non-related

duties such as administrative work, managing student

discipline outside classroom can boost their work

efficiency. One said,

“I’m so happy that I don’t have to patrol around

during lunchtime to keep students in the

classrooms… School office is closed. There are no

students at school. There are almost no

administrative duties and meetings…” (Sam,

Hong Kong)

Another participant, Natalie, also echoed with a

similar statement. She said,

“Now there are no more chores like cleaning

class and yard duty. I don’t need to attend

unscheduled meetings…You know…they are

rather meaningless.” (Natalie, Russia)

In short, participants in this study believed that

online teaching could boost their work efficiency by

maximising the time on desirable teaching-related

activities and minimising the time on undesirable

teaching non-related activities. According to the

SCCT, making progress towards one’s work goal can

obtain well-being (Lent & Brown, 1996, 2008; Lent

et al., 2005). The results of this study showed that

online learning environment is a supportive

environment in which language teachers are more

likely to reach pleasurable positive emotional states

and achieve their career goals (Lent & Brown, 1996,

2008; Lent et al., 2005).

5.2.2 Work-life Balance

Previous studies (Acton & Glasgow, 2015; Burke et

al., 1996; Hastings & Bham, 2003; Iivari et al., 2020;

Leehu & Ditza, 2017; Tsarkov & Hoblyk, 2016)

suggested that teachers have to spare more time on

preparation in an online learning environment, and

their well-being is greatly affected by increased

workloads, leading to stress, burn-out and emotional

and mental exhaustion. This study, on the other hand,

reflected that there is a positive relationship between

online learning and language teachers’ well-being due

to the attainment of personal goals (Lent & Brown,

1996, 2008; Lent et al., 2005). Participants expressed

that work-life balance could be achieved through

working from home. Through online teaching, they

could manage their time better. One said,

“I can utilise my time better...Before the COVID-

19 [pandemic], lots of time was spent on

administrative work, going to school…It’s

tiring… Now I don’t have to travel to work and

switch classrooms [between lessons]… I only

have to work half day.” (Sam, Hong Kong)

Another participant, Melina, resonated with a

similar view. Besides, she also expressed the

proximity to home enable her to fulfil her personal

goals. She said,

“I really wish to doing online [teaching] forever…I

meant I don’t want the pandemic to continue… But

it’s really good to stay at home to work. Back in the

days at school, I could only have little time for

lunch... Sometimes I had sports or yard duties…

Now once I switch off the cam, I can prepare my

lunch…Hot meals...” (Melina, Australia)

The fondness of working from home due to the

attainment of personal goals can be observed among

the participants (Lent & Brown, 1996, 2008; Lent et

al., 2005). For example, one participant, Jason, also

expressed the flexible working hours enriched his

family life. He said,

“I stay at home… He [the participant’s son] is

happy to see me all day round… We play. We

cook… I take him to sleep… Then I get back to

work at night after my son has slept… I feel like

I’m Dad, a real one… I like my family… if

possible, I want to keep this [online learning].”

(Jason, New Zealand)

The above findings affirmed with the previous

studies suggesting that flexible work arrangements

and spending more hours at home can reduce the

teachers’ work stress (Cinamon 2005, Frone 1997).

According to Bandura (1986) and Lent & Brown

(Lent & Brown, 1996), personal goals play a key role

in career choice making as it influences individuals’

perceptions of outcomes. The positive relationship

between work-life balance and personal goal

attainment found in this study affirmed with the

previous study (Guo & Liu, 2020; Johari et al., 2016)

that work-life balance harmonises language teachers’

work and personal life, enriches their life experiences

and they become more motivated and productive.

With the lens of the SCCT, the perceptions and

behaviours affect work and life satisfaction, and

hence language teachers are more likely to continue

online teaching (Lent & Brown, 1996, 2008; Lent et

al., 2005).

Will I Continue Online Teaching? Language Teachers’ Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic

29

5.3 Negative Teaching Outcome

Expectation: Reasons for Stopping

Online Teaching

Scholars (Dungus, 2013; Reeves, 2000) identified

that the major directions of assessments included

cognitive assessment (i.e. assessment on students’

higher-order thinking skills), performance

assessment (i.e. engagement in activities) and

portfolio assessment (i.e. reviewing both students’

work as process and product). In previous sections of

this paper, together with some previous literature

(Blizak et al., 2020; Dos Santos, 2019; Iivari et al.,

2020), language teachers affirmed that cognitive and

performance assessments could be achieved via

features of the online teaching platforms. However,

when it comes to portfolio assessment, language

teachers expressed difficulties in evaluating students’

learning process and achievements. Such difficulties

induce self-doubt and make them postulate a negative

outcome expectation (Lent & Brown, 1996). Such

negative outcome expectation, according to SCCT,

will have a self-hindering effect on teachers’

performance attainment and hampered them to

further continue online teaching (Lent & Brown,

1996, 2008; Lent et al., 2006).

5.3.1 Difficulty in Evaluating Students’

Learning Outcomes

One of the purposes of formative assessment is to

provide on-going feedback and evaluate their

learning outcome (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Lawton et

al., 2012; Ogange et al., 2018). Previous literature

(Hwang et al., 2017; Ogange et al., 2018) suggested

that features in online platforms such as discussion

forums can allow teachers access students’ learning

process. In contrast, the researcher found out in this

research that language teachers did not feel online

platforms are effective means to access students’

instant learning outcome and such uncertainty arose

from a limitation of instant evaluation of students’

learning outcome. One participant said,

“Sometimes teaching is like a monologue…

Teaching is done in one-way… I have covered all

the contents… When I deliver the content well, I

have the illusion that I teach well. In fact, it is hard

to know how much students have learnt.” (Sam,

Hong Kong)

A similar view is shared by another participant:

“I feel insecure because I can never really tell

how well they take everything in…I might prefer

going back to face-to-face teaching… With more

interactions, I know how they learn.” (Catherine,

Canada)

From the findings, this study concluded that

language teachers were sceptical towards students’

learning outcome when effective communications or

active discussions did not happen in their online

lessons (MacIntyre et al., 2020; Perera-Diltz & Moe,

2014). As a result, they felt hard to evaluate students’

learning outcome in the class. Reflected in previous

studies on learning outcomes (Looney et al., 2018;

Skehan, 2003; Taylor & Tyler, 2011), this study

affirmed that when teachers are unable to develop

knowledge on how far students had reached, they

perceive that is a failure damaging their professional

identity. From the lens of the SCCT, the findings in

this study show that such failing experiences can

create self-doubt and constitute a negative learning

experience leading to an avoidance of the similar

future task, i.e. online teaching in this case (Lent &

Brown, 1996, 2008; Lent et al., 2006).

5.3.2 Difficulties in Implementing

Summative Assessment

Summative assessment includes examinations and

tests to measure students’ learning outcome and

achievement (Knight, 2002; Perera-Diltz & Moe,

2014). Previous studies (Chiu et al., 2007; Perera-

Diltz & Moe, 2014) indicated that employing security

measures like lock-down web browsers or text

comparison tools to avoid plagiarism could ensure the

fairness and security of exam procedures. The

findings in this study suggested another view that

language teachers felt fairness was a concern when

they had to conduct summative assessments.

Participants also pointed out that assessment could be

a challenge on an online platform as students’

integrity and honesty were hard to guarantee. One

said,

“Learning is less effective when it’s something

related to assessment… and some tasks that

require a lot of routine practice...like dictations…

It’s hard to manage. You can’t make sure students

aren’t cheating.” (Catherine, Canada)

Another participant, Melina, also expressed a

similar concern. She said,

“It’s hard to do the half-yearly online. You don’t

know whether they rely on some external support

to complete their assessment. Though there is a

declaration form, it doesn’t mean anything. It’s an

honour system anyways.” (Melina, Australia)

From the findings, language teachers feel

powerless in assessing their students. Reflected by the

previous literature (Lynn, 2002; Peeler, 2002), this

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

30

study affirms that powerlessness in quality control

can lead to doubts, turning to an erosion of language

teachers’ beliefs and values due to the diminishing

effectiveness in teaching. The SCCT suggested that

when language teachers experience self-doubt, they

are more likely to postulate a negative image that they

will be unable to attain teaching goals in future (Lent

& Brown, 1996, 2008; Lent et al., 2005). Such

postulation can lower their self-efficacy and perceive

online teaching as a threat and hence more likely they

choose not to persist in online teaching due to the

projected failure (Lent & Brown, 1996, 2008; Lent et

al., 2005).

6 CONCLUSION

This study is a unique international one in examining

the interrelation between personal and contextual

variables influencing language teachers’ perception

of online teaching by adopting a SCCT lens.

Nevertheless, it shows certain limitations. First, most

of the participants are coming from developed

countries. The teachers’ teaching experience may be

limited by the relatively higher socio-economic

backgrounds of the teachers and students. Further

comparative studies can be conducted across higher

and lower socio-economic background to gain an

understanding on the social equity issues (Brown &

Lent, 2019; Flores & Day, 2006; Lent & Brown,

2008). Besides, this study also shows another

limitation as it focuses on the language teachers’

online teaching experience. Further studies can also

be done to examine the experiences of teachers

teaching other subjects such as STEM. They can look

into whether certain significant variables identified in

this study are subject-based or universal (Lent et al.,

2000; Robert & Brown, 2013). Despite the limitations

mentioned above, the findings of this study shed light

on language teachers’ difficulties in evaluating

students’ learning outcomes and implementing

summative assessments using online teaching. The

COVID-19 pandemic has brought a sudden

revolutionary change to both the society and

education. Such insight can be useful for education

policy-makers and school management in reviewing

the current policies and implementation of online

learning to attain both fairness and learning

efficiency, and probe into the possibility of

implementing online teaching as a regular component

in the curriculum.

REFERENCES

Acton, R., & Glasgow, P. (2015). Teacher Wellbeing in

Neoliberal Contexts: A Review of the Literature.

Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(8), 99–

114. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n8.6

Alase, A. (2017). The Interpretative Phenomenological

Analysis (IPA): A Guide to a Good Qualitative

Research Approach. International Journal of Education

and Literacy Studies, 5(2), 9.

https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9

Asanov, I., Flores, F., McKenzie, D., Mensmann, M., &

Schulte, M. (2021). Remote-learning, Time-use, and

Mental Health of Ecuadorian High-school Students

during the COVID-19 quarantine. World Development,

138, 105225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.

105225

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and

Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs,

N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Excercise of

Control. Springer Reference.

Basilaia, G., & Kvavadze, D. (2020). Transition to Online

Education in Schools during a SARS-CoV-2

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in Georgia.

Pedagogical Research, 5(4), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.

29333/pr/7937

Bernard, H. R. (2006). Research Methods in Anthropology:

Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (4

th

ed.).

AltaMira Press.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and Classroom

Learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy

& Practice, 5(1), 7-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/

0969595980050102

Blizak, D., Blizak, S., Bouchenak, O., & Yahiaoui, K.

(2020). Students’ Perceptions Regarding the Abrupt

Transition to Online Learning during the Covid-19

Pandemic: Case of Faculty of Chemistry and

Hydrocarbons at the University of Boumerdes-Algeria.

Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 2466–2471.

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00668

Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (2019). Social Cognitive

Career Theory at 25: Progress in Studying the Domain

Satisfaction and Career Self-Management Models.

Journal of Career Assessment.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072719852736

Burke, R. J., Greenglass, E. R., & Schwarzer, R. (1996).

Predicting Teacher Burnout over Time: Effects of Work

Stress, Social Support, and Self-doubts on Burnout and

its Consequences. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 9(3),

261-275. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615809608249406

Cadenas, G. A., Cisneros, J., Spanierman, L. B., Yi, J., &

Todd, N. R. (2020). Detrimental Effects of Color-Blind

Racial Attitudes in Preparing a Culturally Responsive

Teaching Workforce for Immigrants. Journal of Career

Development, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/

0894845320903380

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical Bases of

Communicative Approaches to Second Language

Will I Continue Online Teaching? Language Teachers’ Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic

31

Teaching and Testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1–47.

https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/I.1.1

Cantrell, P., Young, S., & Moore, A. (2003). Factors

Affecting Science Teaching Efficacy of Preservice

Elementary Teachers. Journal of Science Teacher

Education, 14(3), 177-192. https://doi.org/10.1023/

a:1025974417256

Capri, A., Ronan, D. M., Falconer, H., & Lents, N. H.

(2017). Cultivating Minority Scientists: Undergraduate

Research Increases Self-efficacy and Career Ambitions

for Underrepresented Students in STEM. Journal of

Research in Science Teaching, 54(2), 169–194.

10.1002/tea.21341

Chiu, C. M., Chiu, C. S., & Chang, H. C. (2007). Examining

the Integrated Influence of Fairness and Quality on

Learners’ Satisfaction and Web-based Learning

Continuance Intention. Information Systems Journal,

17(3), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-

2575.2007.00238.x

Cinamon, R. G., & Rich, Y. (2005). Reducing Teachers’

Work-Family Conflict. Journal of Career Development,

32(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/

0894845305277044

Connolly, M. R., Lee, Y. G., & Savoy, J. N. (2018). The

Effects of Doctoral Teaching Development on Early-

career STEM Scholars’ College Teaching Self-efficacy.

CBE Life Sciences Education, 17(1), 1–15.

https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-02-0039

Coulter, C., Michael, C., & Poynor, L. (2007). Storytelling

as Pedagogy : An Unexpected Outcome of Narrative

Inquiry. Curriculum Inquiry, 37(2), 103–122.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Research Design: Qualitative,

Quantitative and Mixed Method Approaches. SAGE

Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative Inquiry and Research

Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches (3

rd

ed..

SAGE Publications.

Dos Santos, L. M. (2019). English Language Learning for

Engineering Students: Application of a Visual-only

Video Teaching Strategy. Global Journal of

Engineering Education, 21(1), 37–44.

Dungus, F. (2013). The Effect of Implementation of

Performance Assessment, Portfolio Assessment and

Written Assessments Toward the Improving of Basic

Physics II. Learning Achievement. 4(14), 111–117.

Ellis, E. M. (2004). The Invisible Multilingual Teacher: The

Contribution of Language Background to Australian

ESL teachers’ professional knowledge and beliefs.

International Journal of Multilingualism, 1(2),90–108.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710408668181

Ellis, R. (2000). Task-based Research and Language

Pedagogy. Language Teaching Research, 4(3), 193–220.

https://doi.org/10.1177/136216880000400302

Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of Convenience Sampling

and Purposive Sampling. American Journal of

Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1.

https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Flores, M. A., & Day, C. (2006). Contexts which Shape and

Reshape New Teachers’ Identities: A Multi-perspective

Study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(2), 219-

232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.002

Fouad, N. A., Kantamneni, N., Smothers, M. K., Chen, Y.

L., Fitzpatrick, M., & Terry, S. (2008). Asian American

Career Development: A Qualitative Analysis. Journal

of Vocational Behavior, 72(1), 43–59.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.10.002

Garrison, D. R., & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2005). Facilitating

Cognitive Presence in Online Learning: Interaction is

Not Enough. American Journal of Distance Education,

19(3), 133-148. https://doi.org/10.1207/

s15389286ajde1903_2

Grant, K. S. L., & Lee, V. J. (2014). Wrestling with Issues

of Diversity in Online Courses. Qualitative Report,

19(6), 1-25.

Guo, J., & Liu, Y. (2020). Navigating the Complex

Landscape of Cross-epistemic Climates: Migrant

Chinese Language Teachers’ Belief Changes about

Knowledge and Learning. Teacher Development, 24(4),

1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2020.1794951

Hackett, G., & Byars, A. M. (1996). Social Cognitive

Theory and the Career Development of African

American Women. Career Development Quarterly,

44(4), 322-340. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-

0045.1996.tb00449.x

Hastings, R. P., & Bham, M. S. (2003). The Relationship

between Student Behaviour Patterns and Teacher

Burnout. School Psychology International, 24(1), 115-

127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034303024001905

Hebert, E., & Worthy, T. (2001). Does the First Year of

Teaching Have to be a Bad One? A Case Study of

Success. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(8), 897–

911. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00039-7

Hwang, Y. S., Bartlett, B., Greben, M., & Hand, K. (2017).

A Systematic Review of Mindfulness Interventions for

In-service Teachers: A Tool to Enhance Teacher

Wellbeing and Performance. Teaching and Teacher

Education, 64, 26–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.

2017.01.015

Hyland, K. (2007). Genre Pedagogy: Language, literacy

and L2 writing instruction. Journal of Second

Language Writing, 16(3), 148–164.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2007.07.005

Iivari, N., Sharma, S., & Ventä-Olkkonen, L. (2020). Digital

Transformation of Everyday life – How COVID-19

Pandemic Transformed the Basic Education of the

Young Generation and Why Information Management

Research Should Care? International Journal of

Information Management, 55(6), 102183.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183

Johari, J., Tan, F. Y., & Zukarnain (2016). Autonomy,

Workload, Worklife Balance and Job Performance

Teachers. International Journal for Researcher

Development, 7(1), 63–83.

Jurkovič, V. (2019). Online Informal Learning of English

through Smartphones in Slovenia. System, 80, 27–37.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.10.007

Knight, P. T. (2002). Summative Assessment in Higher

Education: Practices in Disarray. Studies in Higher

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

32

Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/

03075070220000662

Lawton, D., Vye, N., Bransford, J., Sanders, E., Richey, M.,

French, D., & Stephens, R. (2012). Online Learning

Based on Essential Concepts and Formative

Assessment. Journal of Engineering Education, 101(2),

244–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2012.

tb00050.x

Leehu, Z., & Ditza, M. (2017). Teachers’ Professional

Development, Emotional Experiences and Burnout.

Journal of Advances in Education Research, 2(4).

https://doi.org/10.22606/jaer.2017.24009

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (1996). Social Cognitive

Approach to Career Development: An Overview.

Career Development Quarterly, 44(4), 310-321.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00448.x

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., Schmidt, J., Brenner, B., Lyons,

H., & Treistman, D. (2003). Relation of Contextual

Supports and Barriers to Choice Behavior in

Engineering Majors: Test of Alternative Social

Cognitive Models. Journal of Counseling Psychology,

50(4), 458–465. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-

0167.50.4.458

Lent, R. W. (2004). Toward a Unifying Theoretical and

Practical Perspective on Well-Being and Psychosocial

Adjustment. In Journal of Counselling Psychology,

51(4), 482-509. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-

0167.51.4.482

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2006). Integrating Person and

Situation Perspectives on Work Satisfaction: A Social-

cognitive View. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69 (2),

236-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.02.006

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2008). Social Cognitive

Career Theory and Subjective Well-being in the

Context of Work. Journal of Career Assessment, 16 (1),

6-21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707305769

Looney, A., Cumming, J., van Der Kleij, F., & Harris, K.

(2018). Reconceptualising the Role of Teachers as

Assessors: Teacher Assessment Identity. Assessment in

Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 25(5), 442–

467. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2016.1268090

Lynn, S. K. (2002). The Winding Path: Understanding the

Career Cycle of Teachers. The Clearing House: A

Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas,

75(4), 179–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/

00098650209604926

MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., & Mercer, S. (2020).

Language Teachers’ Coping Strategies during the

Covid-19 Conversion to Online Teaching: Correlations

with Stress, Wellbeing and Negative emotions. System,

94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102352

Manegre, M., & Sabiri, K. A. (2020). Online Language

Learning Using Virtual Classrooms: an Analysis of

Teacher Perceptions. Computer Assisted Language

Learning, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.

2020.1770290

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative Research: A Guide to

Design and Implementation. Jossey-Bass.

Moustakas, C. E. (1994). Phenomenological Research

Methods. Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/

9781412995658

Nauta, M. M., & Epperson, D. L. (2003). A Longitudinal

Examination of the Social-cognitive Model Applied to

High School Girls’ Choices of Nontraditional College

Majors and Aspirations. Journal of Counseling

Psychology, 50(4), 448-457. https://doi.org/10.1037/

0022-0167.50.4.448

Ogange, B. O., Agak, J., Okelo, K. O., & Kiprotich, P.

(2018). Student Perceptions of the Effectiveness of

Formative Assessment in an Online Learning

Environment. Open Praxis, 10(1), 29.

https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.1.705

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research and Evaluation

Methods. Sage Publications

Peeler, E. (2002). Changing Culture, Changing Practice :

Overseas-born teachers in Victorian educational

contexts. In the Australian Association for Research in

Education Conference, Brisbane 2002

Peirce, B. N. (1995). Social Identity, Investment, and

Language Learning. TESOL Quarterly, 29(1), 9–31.

Perera-Diltz, D., & Moe, J. (2014). Formative and

Summative Assessment in Online Education. Journal

of Research in Innovative Teaching, 7(1), 130–142.

Pham, T. T. L., Teng, C. I., Friesner, D., Li, K., Wu, W. E.,

Liao, Y. N., Chang, Y. T., & Chu, T. L. (2019). The

Impact of Mentor–mentee Rapport on Nurses’

Professional Turnover Intention: Perspectives of Social

Capital Theory and Social Cognitive Career Theory.

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(13–14), 2669–2680.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14858

Placer, J. H., & Dodds, P. (1988). A Critical Incident Study

of Preservice Teachers’ Beliefs about Teaching Success

and Nonsuccess. Research Quarterly for Exercise and

Sport, 59(4), 351-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/

02701367.1988.10609382

Powazny, S., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). The Impact of

Influential Others on Student Teachers’ Dropout

Intention–a Network Analytical Study. European

Journal of Teacher Education, 2020, 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1793949

Pringle, J., Drummond, J., McLafferty, E., & Hendry, C.

(2011). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: A

discussion and Critique. Nurse Researcher, 18(3), 20–

24. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2011.04.18.3.20.c8459

Reeves, T. C. (2000). Alternative Assessment Approaches

for Online Learning Environments in Higher Education.

Journal of Educational Computing Research, 23(1),

101–111. https://doi.org/10.2190/GYMQ-78FA-

WMTX-J06C

Robert, W., & Brown, S. D. (2013). Social Cognitive Model

of Career Self-Management : Toward a Unifying View

of Adaptive Career Behavior Across the Life Span.

60(4), 557–568.

Rovai, A. P. (2007). Facilitating Online Discussions

Effectively. Internet and Higher Education, 10(1), 77–

88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2006.10.001

Sachs, J. D., Schmidt-Traub, G., Mazzucato, M., Messner,

D., Nakicenovic, N., & Rockström, J. (2019). Six

Will I Continue Online Teaching? Language Teachers’ Experience during the COVID-19 Pandemic

33

Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable

Development Goals. Nature Sustainability, 2(9), 805–

814. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0352-9

Seidman, I. (2013). Interviewing as Qualitative Research.

Teacher College Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/032390

Skehan, P. (2003). Task-based Instruction. Language

Teaching, 36(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1017/

S026144480200188X

Slezak, P. (1991). Bloor’s Bluff: Behaviourism and the

Strong Programme. International Studies in the

Philosophy of Science, 5(3), 241–256.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02698599108573397

Smith, J. A. (2004). Reflecting on the Development of

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis and its

Contribution to Qualitative Research in Psychology.

Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1(1), 39-54.

https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088704qp004oa

Smith, J. A. (2015). Qualitative Psychology: A Practical

Guide to Research Methods (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2008). Interpretative

Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and

Research. In Qualitative Psychology, A Practical Guide

to Research Methods. Sage Publications.

Smith, J., Flowers, J., & Larkin, M. (2005). The Theoretical

Foundations of IPA. In Interpretative

Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and

Research. Sage Publications.

Sparks, D. M., & Pole, K. (2019). “Do we Teach Subjects

or Students?” Analyzing Science and Mathematics

Teacher Conversations about Issues of Equity in the

Classroom. School Science and Mathematics, 119(7),

405–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssm.12361

Stodel, E. J., & Thompson, T. L. (2006). Interpretations

through the Community of Inquiry Framework. The

International Review of Research in Open and

Distributed Learning, 7(3), 1–15.

Talbot, D. C. (1982). Language Practice Drills: Their

Usefulness and Shortcomings. Teaching and Learning,

3(1), 37–40.

Taylor, E., & Tyler, J. (2011). The Effect of Evaluation on

Performance: Evidence from Longitudinal Student

Achievement Data of Mid-Career Teachers. NBER

Working Paper No. 16877. National Bureau of

Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w16877

Terrell, S. R. (2005). A Longitudinal Investigation of the

Effect of Information Perception and Focus on Attrition

in Online Learning Environments. Internet and Higher

Education, 8(3), 213–219.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2005.06.003

The United Nations. (2020).

Policy Brief: Education during

COVID-19 and beyond. https://www.un.org/

development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/

2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_

august_2020.pdf

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A General Inductive Approach for

Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. American

Journal of Evaluation. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1098214005283748

Tsarkov, P. E., & Hoblyk, V. V. (2016). Teachers in Russian

schools: Working Conditions and Causes of

Dissatisfaction. Mathematics Education, 11(9), 3243–

3260.

Vial, G. (2019). Understanding Digital Transformation: A

Review and a Research Agenda. In Journal of Strategic

Information Systems, 28(2), 118-144.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2019.01.003

Wang, X. (2013). Why Students Choose STEM Majors:

Motivation, High School Learning, and Postsecondary

Context of Support. American Educational Research

Journal, 50(5), 1081–1121. https://doi.org/10.3102/

0002831213488622

Welch, J. K., & Patton, M. Q. (1992). Qualitative

Evaluation and Research Methods. The Modern

Language Journal, 76(4), 543-544.

https://doi.org/10.2307/330063

CSEDU 2021 - 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

34