Developing Cyber-risk Centric Courses and Training Material for

Cyber Ranges: A Systematic Approach

Gencer Erdogan

1

, Antonio Álvarez Romero

2

, Niccolò Zazzeri

3

, Anže Žitnik

4

, Mariano Basile

5

,

Giorgio Aprile

6

, Mafalda Osório

7

, Claudia Pani

8

and Ioannis Kechaoglou

9

1

Software and Service Innovation, SINTEF Digital, Oslo, Norway

2

Research & Innovation, Atos, Seville, Spain

3

Trust-IT Services, Pisa, Italy

4

XLAB, Ljubljana, Slovenia

5

Department of Information Engineering, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

6

Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane, Rome, Italy

7

Energias de Portugal, Lisboa, Portugal

8

AON, Milan, Italy

9

Rhea Group, Redu, Belgium

mariano.basile@ing.unipi.it, g.aprile@fsitaliane.it, mafalda.osorio@edp.com, claudia.pani@aon.it,

i.kechaoglou@rheagroup.com

Keywords: Security Education, Security Awareness, Cyber Range, Cyber Risk, Course, Training, Cybersecurity, Security

Roles, Security Skills, White Team, Green Team, Red Team, Blue Team.

Abstract: The use of cyber ranges to train and develop cybersecurity skills and awareness is attracting more attention,

both in public and private organizations. However, cyber ranges typically focus mainly on hands-on exercises

and do not consider aspects such as courses, learning goals and learning objectives, specific skills to train and

develop, etc. We address this gap by proposing a method for developing courses and training material based

on identified roles and skills to be trained in cyber ranges. Our method has been used by people with different

background grouped in academia, critical infrastructure, research, and service providers who have developed

22 courses including hands-on exercises. The developed courses have been tried out in pilot studies by SMEs.

Our assessment shows that the method is feasible and that it considers learning and educational aspects by

facilitating the development of courses and training material for specific cybersecurity roles and skills.

1 INTRODUCTION

A cyber range is an environment that simulates

infrastructures and cyber-attacks the infrastructures

are exposed to, for example, cyber-attacks carried out

on critical energy infrastructure. The simulated

infrastructure acts as a testbed on which real-world

attack and defence scenarios can be applied for the

purpose of cybersecurity training and response

preparedness.

Cyber ranges have traditionally been developed

and used by military institutions for cybersecurity

training in the context of homeland defence strategy

(Damodaran & Smith, 2015; Davis & Magrath, 2013;

Ferguson, Tall, & Olsen, 2014). However, the use of

cyber ranges to train and develop cybersecurity skills

and awareness is attracting more attention, both in

public and private organizations.

Independent of the domain in which they are used,

cyber ranges mainly provide hands-on exercises that

are ready to be integrated as part of a security training

programme. We refer to this as a bottom-up approach

where exercises are first developed for training

purposes and then integrated in various cybersecurity

training programmes to teach about certain cyber-

attacks. Although this approach is useful, the

exercises are typically not developed based on the

needs of specific cybersecurity roles. For example, a

course that teaches about SQL injection may be

different depending on the target role; a security

manager may be interested in understanding the

business impact of SQL injection attacks, while a

vulnerability assessment analyst may be interested in

702

Erdogan, G., Romero, A., Zazzeri, N., Žitnik, A., Basile, M., Aprile, G., Osório, M., Pani, C. and Kechaoglou, I.

Developing Cyber-risk Centric Courses and Training Material for Cyber Ranges: A Systematic Approach.

DOI: 10.5220/0010393107020713

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP 2021), pages 702-713

ISBN: 978-989-758-491-6

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

learning about the technical vulnerabilities and

weaknesses that opens for SQL injection attacks.

There exist many courses related to cybersecurity

at both business level as well as technical level

(CIISec, 2020a; MITRE, 2020; SANS, 2020).

However, the literature lacks approaches that may

help instructors systematically develop courses and

training material by first identifying roles and skills

to be trained on a cyber range, and then shape the

training material and exercises according to the

learning goals and objectives for the identified roles.

We refer to this as a top-down approach and view

such approaches as complementary to the bottom-up

approaches.

Thus, the contribution of this paper is a method

for developing courses and training material based on

identified roles and skills to be trained in cyber

ranges. That is, a top-down approach as described

above. In addition, our approach is novel in the sense

that we cluster courses, roles, and skills with respect

to steps of standard cyber-risk assessment processes

(ISO, 2018) to construct a cyber-risk centric learning

path.

Cyber ranges often have different participants

referred to as "teams" who have different roles. In this

paper, we consider the White, Green, Red, and Blue

teams (Damodaran & Smith, 2015). The White Team

represents the instructor/s of the training, whether

course based or as an exercise. The White Team

collaborates with the Green Team to deploy and

configure training scenarios. The Green Team

consists of individuals who operate the cyber range

infrastructure. In collaboration with the White Team,

the Green Team manages on-demand development of

training scenarios. The White Team also evaluates the

participants' progress. The Red Team carries out

cyberattacks against the infrastructure simulated on

the cyber range as part of a training scenario. The

Blue Team detects and responds to the attacks

performed by the Red Team and/or automatically by

the tools in the cyber range. The intended users of the

method reported in this paper are the participants of a

White/Green team, that is the instructors, to develop

courses and training material. The end users of the

courses and training material developed are the

participants of a Red/Blue team.

Section 2 describes the method for developing

cyber-risk centric courses and training material.

Section 3 provides related work, while in Section 4

we discuss our experience in using the method in real-

world scenarios and lessons learned. Finally, in

Section 5, we provide conclusions.

2 METHOD FOR DEVELOPING

CYBER-RISK CENTRIC

COURSES AND TRAINING

MATERIAL

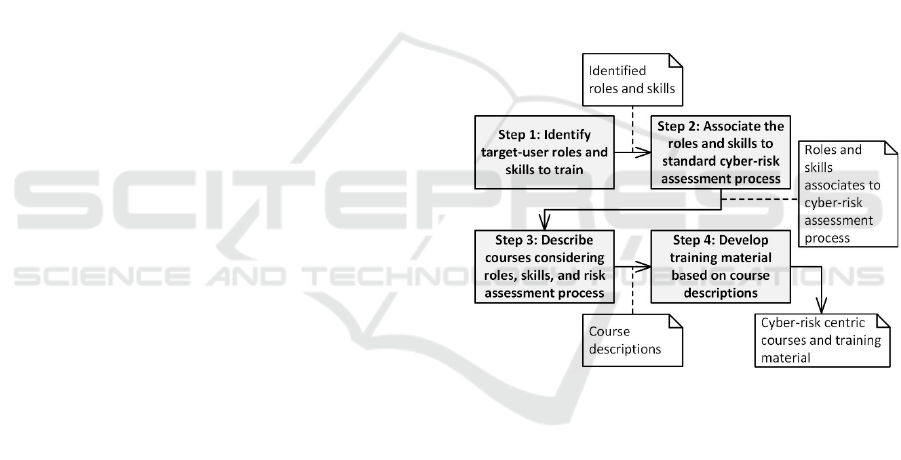

Figure 1 illustrates the steps of our method to

systematically develop cyber-risk centric courses and

training material.

In Step 1, we identify the target-user cybersecurity

roles for whom we will create courses and training

material, and describe the skills required by the roles

as well as the expected level of advancement for each

skill. The objective is to identify roles and skill that

are relevant in a standard cyber-risk assessment

process. For example, roles such as Information

Security Risk Manager and Vulnerability Assessment

Analyst, and skills like Risk Assessment and Threat

Modelling. The output of Step 1 is a set of identified

roles and skills.

Figure 1: Method for developing cyber-risk centric courses

and training material.

In Step 2, we associate the identified roles and

skills to appropriate steps of a standard risk

assessment process. With respect to risk assessment

process, we base ourselves on ISO 27005 (ISO,

2018). The output of Step 2 is a set of roles, including

their skills, associated to relevant steps of a standard

risk assessment process.

In Step 3, we describe courses considering the

needs of the roles identified in Step 1. The objective

is to describe courses to train the expected skills

necessary to successfully execute the relevant step of

the risk assessment process. The output of Step 3 is a

set of course descriptions.

Finally, in Step 4, we develop the training material

for each course with respect to the course

descriptions. The output of the final step is thus a set

Developing Cyber-risk Centric Courses and Training Material for Cyber Ranges: A Systematic Approach

703

of cyber-risk centric courses and training material for

specific set of roles to be trained. The courses and

training material are packaged as Shareable Content

Object Reference Model (SCORM) files and ready to

be integrated in cyber ranges supported by learning

management systems capable of processing SCORM

files. The method reported in this paper stops with the

completion of Step 4. As part of developing training

material in context of cyber ranges, we also need to

develop appropriate hands-on exercises for the

courses. However, this is covered in our previous

work where we explain how to develop training

scenarios on cyber ranges based on cyber-risk models

(G. Erdogan et al., 2020a). Developing hands-on

training exercises for cyber ranges is therefore not

covered in this paper.

The following sections describe in detail each step

of the method outlined in Figure 1.

2.1 Step 1: Identify Target-user Roles

and Skills to Train

There exist several cybersecurity communities and

frameworks that may be used as a basis to identify

and select cybersecurity roles and their expected

skills, such as MITRE (MITRE, 2020), OWASP

(OWASP, 2020), CIISec (CIISec, 2020b, 2020c), and

SANS (SANS, 2020) to mention a few. We chose to

use the CIISec Roles Framework and the CIISec

Skills Framework for our method.

The CIISec Roles Framework by the Chartered

Institute of Information Security (CIISec, 2020b)

provides a list of security roles and associates these

roles to certain skills and expected skill levels. The

framework is mainly intended for organizations when

they are looking to recruit into a role. However, in our

approach we use these roles in combination with the

skills described in the CIISec Skills Framework

(CIISec, 2020c) to systematically identify the target

users to train as well as to appropriately shape the

courses and training material. The roles we selected

from the CIISec Roles Framework are those that align

with our risk-centric approach focusing on skills

related to Threat Assessment and Information Risk

Management. Based on these criteria, we selected the

following roles:

R1: Head of Information/Cyber Security

R2: Information Security Risk Manager

R3: Information Security Risk Officer

R4: Threat Analyst

R5: Vulnerability Assessment Analyst

According to CIISec, the Skills Framework

(CIISec, 2020c) describes the range of competencies

expected of Information Security and Information

Assurance Professionals in the effective performance

of their roles. The framework may be used as a basis

to assess the knowledge of certain security roles as

well as to define skills expected of the security roles

in practice. The CIISec Skills Framework is

complementary to the CIISec Roles Framework

described above. Each of the roles (R1–R5) have

various relevant skills assigned to them. As

mentioned above, the skills we selected for the above

roles are related to threat assessment and information

risk management. The relevant skills, based on the

Skills Framework, are thus:

S1: Threat Intelligence, Assessment and Threat

Modelling

S2: Risk Assessment

S3: Information Risk Management

The rationales to why we chose the CIISec Roles

Framework and the CIISec Skills Framework as the

basis in our approach to identify target-user roles and

skills are summarized by the following points.

The CIISec Roles Framework and the CIISec

Skills Framework are considering roles and

skills that are well aligned with our risk-centric

approach. For example, the role Information

Security Risk Officer (R3) and the associated

skills Risk Assessment (S2) and Information

Risk Management (S3) are relevant for

standard cyber-risk assessment processes.

Each role defined in the CIISec Roles

Framework are associated to certain skills and

expected skill level, which provides a good

indication to define course difficulty (level of

advancement) in the next steps of our method.

The CIISec Skills Framework describes six

skill levels {Knowledge (level 1), Knowledge

and Understanding (level 2), Apply (level 3),

Enable (level 4), Advice (level 5), Initiate,

Enable and Ensure (level 6)}. These six levels

align well with the six levels of advancement in

learning skills provided by the Bloom's

taxonomy (Anderson & Bloom, 2001) which

are {Remembering (level 1), Understanding

(level 2), Applying (level 3), Analysing (level

4), Evaluating (level 5), Creating (level 6)}. As

best practice, we use the action verbs provided

by Bloom's taxonomy to help describe the

learning goals and objectives of the courses

when describing courses in the next steps. It is

beyond the scope of this paper to describe the

Bloom's taxonomy. The reader is referred to

Anderson and Bloom (2001) for detailed

description of the Bloom's taxonomy.

The cyber-risk related roles and skills

described

in the CIISec frameworks are well

ICISSP 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

704

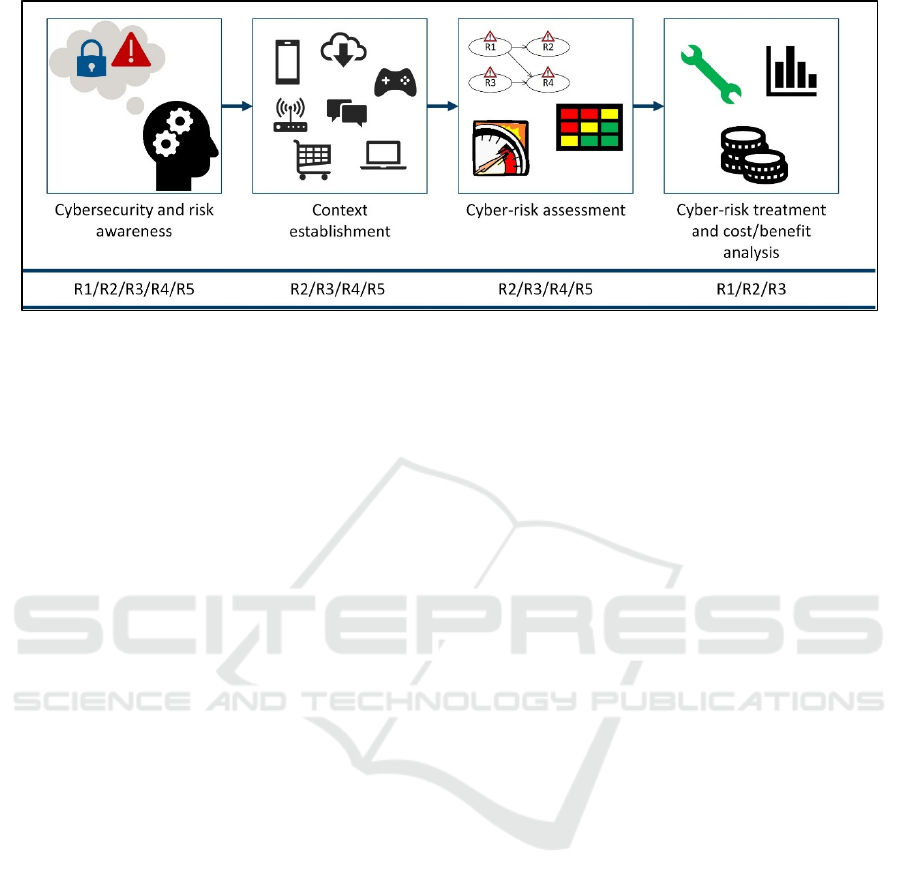

Figure 2: Roles (R1–R5) associated to the steps of cyber-risk management. This association acts also as a cyber-risk centric

learning path.

aligned with standard cyber-risk assessment,

such as ISO 27005 (ISO, 2018), and therefore

support our risk-centric approach.

2.2 Step 2: Associate the Roles and

Skills to Standard Cyber-risk

Assessment Process

As illustrated in Figure 2, the roles identified in

Section 2.1 are associated to the following main parts

of cyber-risk management:

Cybersecurity and risk awareness

Context establishment

Cyber-risk assessment

Cyber-risk treatment and cost/benefit analysis

We group the roles under these points based on

their expected skills, which will later in the process

help us shape courses and training material according

to roles, skills, and the underlying cyber-risk

management step.

The first step (Cybersecurity and risk awareness)

is not part of a traditional cyber-risk management

process, but we have included this point to create

courses that prepare participants in becoming familiar

with cybersecurity and cyber-risk related concepts

before proceeding to the next three steps. The

remaining three steps (context establishment, cyber-

risk assessment, and cyber-risk treatment and

cost/benefit analysis) are steps found in standard

cyber-risk management processes such as in ISO

27005 (ISO, 2018). Moreover, the order in which the

steps are listed above are typically carried out

consecutively and we utilize this order as the overall

risk centric learning path that participants can follow.

Although the cyber-risk management steps are

illustrated as consecutive steps in Figure 2, the

courses that later are linked to each step do not have

to be carried out consecutively. Depending on the

previous knowledge and skills of the participants, a

participant may choose to obtain training in one or

more parts of the learning path captured in Figure 2

by selecting appropriate courses. Some courses may

also cover more than one part of the learning path. For

someone with little or basic cybersecurity knowledge,

we suggest following the steps as illustrated in Figure

2.

The positioning of the roles in relation to the

learning path illustrated in Figure 2 is based on the

description of these roles as provided by the CIISec

Roles Framework (CIISec, 2020b). As pointed out by

the CIISec Roles Framework, the role descriptions, as

well as the skills required by the roles, may vary

because of factors such as the size of the organisation,

complexity, sector, and business model. This means

that the mapping in Figure 2 may also vary among

different organizations. However, given that the

CIISec Roles Framework has been "developed

through collaboration between both private and

public sector organisations and world-renowned

academics and security leaders" (CIISec, 2020c) the

mapping will apply in most cases.

All the roles mentioned in Section 2.1 need to be

aware of the basics of cyber-risk management such as

domain specific concepts and processes. All roles

therefore fit under the first part of the learning path

(cybersecurity and risk awareness).

Role R1 fit mainly under cyber-risk treatment and

cost-benefit analysis because the role is typically at

senior management level who decides, among other

things, the value of certain security assets and

whether certain risks that may harm the assets should

be treated or not based on treatment cost.

The roles R2 and R3 fit in all parts of the learning

path because these roles must ensure that

Developing Cyber-risk Centric Courses and Training Material for Cyber Ranges: A Systematic Approach

705

cybersecurity risks are identified and assessed. These

roles must also make appropriate recommendations

based on the risk assessment results and are typically

in charge of leading cyber-risk management tasks

such as context establishment, cyber-risk assessment,

and cyber-risk treatment and cost/benefit analysis.

The roles R4 and R5 are more technical in nature

and collect, process, analyse and disseminate threat

assessments and cyber-risk indicators. These roles

also identify weaknesses using known vulnerabilities

and common configuration faults to obtain a risk

picture. Thus, roles R4 and R5 fit under the context

establishment and the cyber-risk assessment parts of

the learning path.

2.3 Step 3: Describe Courses

Considering Roles, Skills, and Risk

Assessment Process

To organize courses in our method, we use the

approach provided by the SANS institute (SANS,

2020), which is one of the largest sources for

cybersecurity training and certification.

We structure the courses in two main layers,

namely course and module. A course contains a set of

modules. A module may be part of one or more

courses. The idea behind this separation is to shape

more complex courses using simpler modules, where

each module brings smaller contributions. Moreover,

modules will help participants increase their skills by

progressing step by step in the learning path.

We describe courses using templates considering

the roles, skills, and the risk assessment process

described in previous sections. That is, each course is

shaped for one or more of the roles listed in Section

2.1 and specifies which skill and skill level is trained

as part of the course. A course may be relevant for

one or more parts of the learning path depicted in

Figure 2. The courses are described using the course

and module templates shown in Table 1 and Table 2,

respectively.

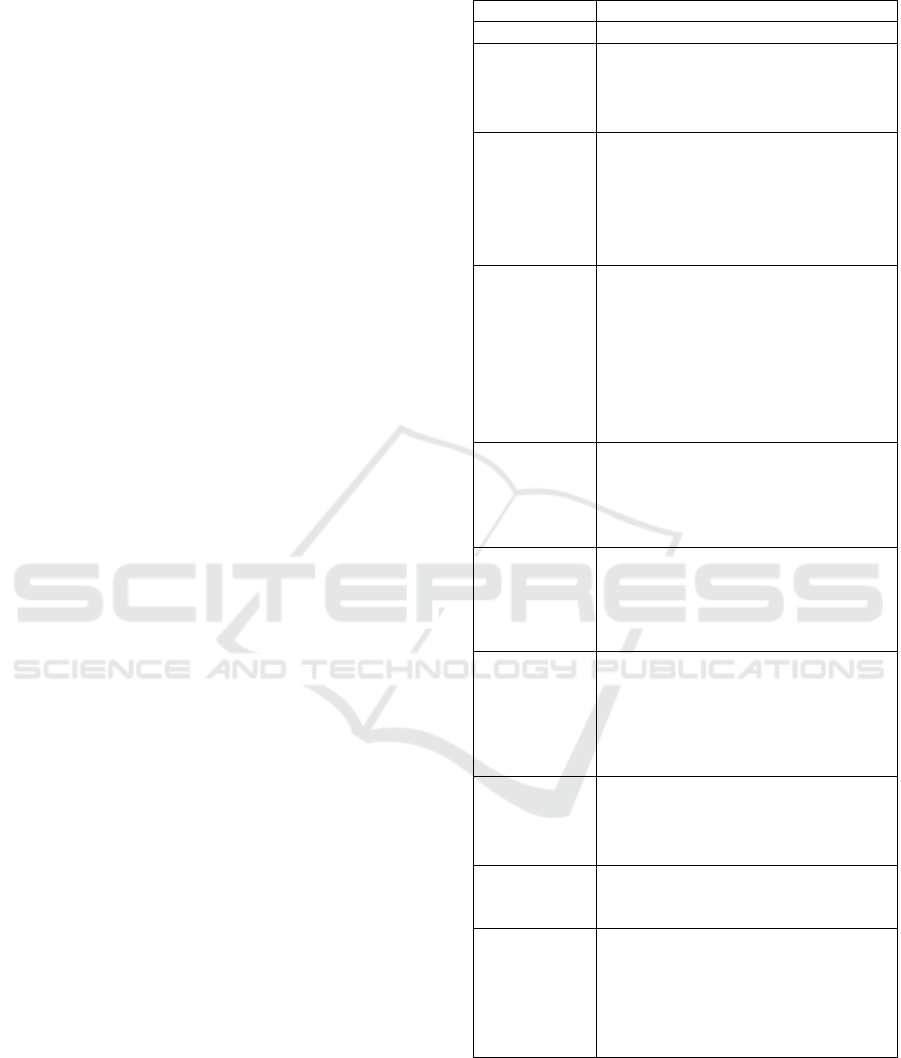

The left column of the course template in Table 1

represents all attributes needed to describe a course,

while the right column consists of guiding text for

each attribute. The users of this template need to

replace the guiding text with relevant information to

describe a course.

Table 1: Course template.

Course ID Uni

q

ue ID fo

r

the course.

Name Name of the course.

Cybersecurity

role

The cybersecurity role relevant to the

course. These roles are based on the

roles described by the CIISec Roles

Framework (CIISec, 2020b).

Skill and

expected skill

level to be

trained

The skill and the expected level of

advancement of the skill. The skill is

defined for the abovementioned role.

These skills and skill levels are based

on the CIISec Skills Framework

(CIISec, 2020c).

Step in risk

assessment

process

Select which step of the risk

assessment process depicted in Figure

N this course addresses. You may

select one or more options

{Cybersecurity and risk awareness,

Context establishment, Cyber-risk

assessment, and Cyber-risk treatment

and cost/benefit analysis}.

Difficulty Difficulty level of the course. Possible

options are {Easy, Medium, Hard,

Challenging}. This value is provided

based on expert judgment of the

p

erson develo

p

in

g

the course.

Course

Duration

Time needed to carry out the course in

minutes. If the course contains several

modules, then the duration of the

course is the sum of the duration of

the modules.

Learning

Goals

Learning goals of the course. The

learning goals are written using

Bloom's Taxonomy (Anderson &

Bloom, 2001) indicating the broad

learning outcome course participants

will ac

q

uire at the end of the course.

Learning

Objectives

Measurable learning objectives.

The learning objectives are written

using Bloom's Taxonomy (Anderson

& Bloom, 2001).

Prerequisites List of prerequisites for the participant

attending the course. Prerequisites

may be degree level or skills.

Module list List here all the modules related to

this course or write "None" if there are

no modules.

Module 1

Module 2

Module N

Like the course template, we use a module

template to describe modules as shown in Table 2.

ICISSP 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

706

Table 2: Module template.

Module ID Uni

q

ue ID fo

r

the module.

Name Name of the module.

Learning

Objectives

Measurable learning objectives. The

learning objectives are written using

Bloom's Taxonomy (Anderson &

Bloom, 2001).

Module

Duration

Time needed to carry out the module

in minutes.

Prerequisites List of the module(s) that needs to be

attended before this module, or other

general knowledge the participant

should have before carrying out this

module. If no other modules are

needed before this one, fill this field

with “None”.

Content list List here all the contents related to this

module. Contents will show a more

granular division in the module’s topic:

Content 1

Content 2

Content N

Table 3 shows an example usage of the course

template in which we describe a course named

Introduction to cyber-risk assessment. The roles and

skills relevant for this course are described in Section

2.1. However, as can be seen from Table 3, we also

identify a level for each skill to be trained. For the

sake of completeness, we describe in the following

the level of skills listed in Table 3.

For the roles R2 (Information Security Risk

Manager) and R3 (Information Security Risk

Officer), we have pointed out that the skill to be

trained in course C-07 is S2 (Risk Assessment).

Moreover, by taking this course, the participants will

develop the skill S2 in Levels 1 and 2. Achieving

Level 1 for Skill S2 means that the participant can

describe the concepts and principles of risk

assessment, while achieving Level 2 for Skill S2

means that the participant can explain the principles

of risk assessment. This might include experience of

applying risk assessment principles in a training or

academic environment, for example through

participation in syndicate exercises, undertaking

practical exercises, and/or passing a test or

examination (CIISec, 2020c).

For the roles R4 (Threat Analyst) and R5

(Vulnerability Assessment Analyst), we have pointed

out that the skill to be trained in course C-07 is S1

(Threat Intelligence, Assessment and Threat

Modelling). Moreover, by taking this course, the

participants will develop the skill S1 in Level 1.

Achieving Level 1 for Skill S1 means that the

participant can describe the principles of threat

intelligence, modelling, and assessment (CIISec,

2020c).

Table 3: Course about introduction to cyber-risk

assessment.

Course ID C-07

Name Introduction to c

y

be

r

-risk assessment

Cybersecurity

role

R2, R3, R4, R5

Skill and

expected skill

level to be

trained

R2 – Skill S2, Level 1, Level 2.

R3 – Skill S2, Level 1, Level 2.

R4 – Skill S1, Level 1.

R5 – Skill S1, Level 1.

Part in risk

assessment

p

rocess

Cyber-risk assessment

Difficult

y

Mediu

m

Course

Duration

45 minutes

Learning

Goals

It is expected that by the end of this

course, participants in this course will

understand the purpose of cyber-risk

assessment and the activities typically

covered within cyber-risk assessment.

The participants will also understand

the principles of model-based

a

pp

roaches to risk assessment.

Learning

Objectives

To determine whether the participants

have achieved the learning goals, it is

expected that participants, by the end

of the course, will be able to describe

at high-level the activities typically

carried out in cyber-risk assessment

including:

Risk identification

Risk estimation

Risk evaluation

Prerequisites

Complete course C-01

Introduction to cyber-risk

analysis and cybersecurity.

General knowledge within

information technology is an

advantage, but not a requirement.

Module list No modules for this course. The

training material for Introduction to

cyber-risk assessment consists of:

PowerPoint presentation

Review questions as part of the

presentation

Exam questions at the end of the

presentation

Compendium

Audio support

The course in Table 3 is one of 22 courses we

developed as part of the international EU project

named CYBERWISER.eu (CYBERWISER.eu, 2020)

Developing Cyber-risk Centric Courses and Training Material for Cyber Ranges: A Systematic Approach

707

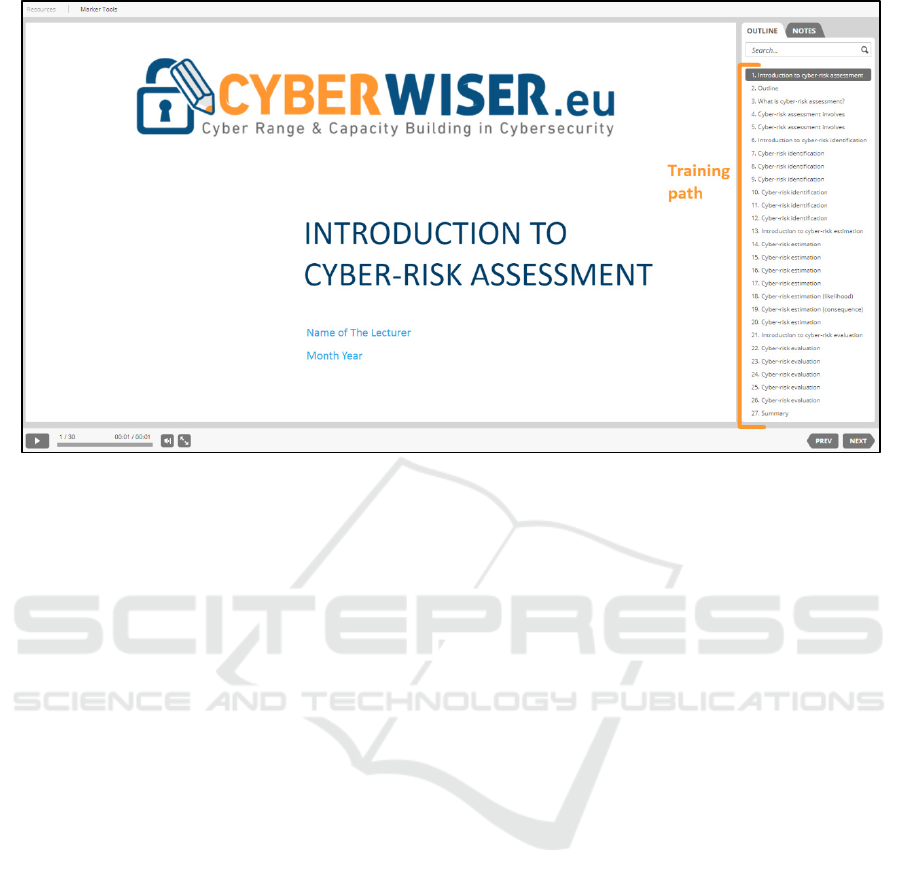

Figure 3: A screenshot from our cyber range showing the course Introduction to cyber-risk assessment.

by applying the method documented in this paper. Due

to space restrictions, we cannot describe all the 22

courses. We therefore refer the reader to our public

report (Gencer Erdogan et al., 2020b) in which all 22

courses and their modules are described in detail.

2.4 Step 4: Develop Training Material

based on Course Descriptions

Finally, having identified and described a set of

courses in Step 3, next we develop training material

for the courses in Step 4.

The training material for a course is developed

with respect to the learning goals and learning

objectives defined for the course, as well as the

cybersecurity roles and skills the course is intended

for. The procedure of shaping courses according to

learning objectives and goals is recommended by

standard course design guidelines, such as Bloom's

Taxonomy (Anderson & Bloom, 2001), which is also

the framework we used to define learning goals and

objectives as described in Section 2.3. We develop

the learning material in terms of:

PowerPoint slides for each course

Supporting literature (compendium) for each

course including references to external sources

Audio support for the PowerPoint slides

Questionnaires testing the participants during the

course (review questions)

Exam questionnaire at the end of the course

(exam quizzes).

The training materials developed are packaged

into SCORM files and then integrated in our online

cyber range platform which we have reported in

earlier work (Basile, Varano, & Dini, 2020; G.

Erdogan et al., 2020a). Our cyber range platform

makes use of Moodle, which is an open-source

learning platform, to host a course.

Figure 3 is a screenshot from our cyber range in

which we see the view a participant sees when taking

a course. In this case, the course shown is

Introduction to cyber-risk assessment, which is the

course described in Table 3.

The complete learning material is accessible to the

participant via this view. The slides of the course are

selectable on the outline tab on the right-hand side.

Each slide has integrated audio support that is

possible to play as illustrated on the lower-left corner

of Figure 3. The audio support is a voice-over

narration explaining the content of the slide as a

teacher (White Team). The participant may also

download the accompanying compendium or view it

on the notes tab on the right-hand side of Figure 3.

The review questions and the exam quizzes are

integrated as part of the course and provided to the

participant half-way into the course and at the end of

the course, respectively. The more advanced courses

(see Table 5) have also a direct link to hands-on

exercises on the cyber range.

ICISSP 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

708

3 RELATED WORK

As mentioned in previous sections, there is a lack of

approaches that systematically starts by identifying

roles and skills to be trained on a cyber range, and

then shape the training material and exercises

accordingly. According to Pfrang, Kippe, Meier, and

Haas (2016), one of the main issues in early cyber

ranges was that they did not consider learning and

educational aspects such as courses, learning goals

and learning objectives, specific skills to train and

develop, etc. A recent literature review by Yamin,

Katt, and Gkioulos (2020), shows that cyber ranges

have advanced within the aspects of monitoring,

scenario development and management, environment

generation and hardware, teaming in terms of

red/blue/white/green/autonomous teams,

management of the cyber range, and learning in the

sense of tutoring, scoring and evaluating student

performance. However, there is still a gap to cover

with respect to learning and educational aspects in

terms of systematic development of courses and

training material. Our method explicitly includes

learning and educational aspects such as courses,

learning goals and objectives, specific skills to train

and develop, etc. as explained in previous sections.

To the best of our knowledge, the approach

reported in this paper is a first attempt in providing a

systematic "top-down" approach starting with roles

and producing risk-centric courses and training

material to be used in context of cyber ranges,

specialized for certain cybersecurity roles and their

skills. The approach most similar to our approach is a

Learning Management System developed by

Carnegie Mellon University named STEPfwd (CMU,

2020). STEPfwd provides both theoretical and

practical cybersecurity skill set in a realistic

environment. It achieves this by combining multiple

choice questions with simulation/emulation labs.

However, STEPfwd does not start by identifying

specific cybersecurity roles as a basis for building and

providing courses and training material as in our

approach.

Regarding "bottom-up approaches", the literature

reports on several approaches where exercises are

first developed for training purposes and then

integrated in various cybersecurity training

programmes. Secure Eggs (Essentials and Global

Guidance for Security) by NRI Secure (NRISecure,

2020), enPiT-Security (SecCap) (EnpitSecurity,

2020), and CYber Defense Exercise with Recurrence

(CYDER) are approaches and security training

programs focusing on basic cybersecurity hands on

and awareness training (Beuran, Chinen, Tan, &

Shinoda, 2016).

There are various approaches focusing on

cybersecurity skills training within specific domains

such as smart grid (Ashok, Krishnaswamy, &

Govindarasu, 2016) and cybersecurity assurance

(Somarakis, Smyrlis, Fysarakis, & Spanoudakis,

2019).

Several approaches focus mainly on the cyber

range architecture and improving the efficiency and

performance of cyber ranges. Pham, Tang, Chinen,

and Beuran (2016) suggest a cyber range framework

named CyRIS/CyTrONE focusing on improving the

accuracy of the training setup, decreasing the setup

time and cost, and making training possible

repeatedly and for a large number of participants.

4 DISCUSSION

In the following, we discuss the feasibility of our

approach as well as observations and lessons learned

we believe is worth sharing with the community to

further improve the development of courses and

training material for cybersecurity training in context

of cyber ranges. We also provide initial feedback

from end users who have taken some of our courses

using the platform as part of piloting exercises in the

CYBERWISER.eu project (CYBERWISER.eu,

2020), which is also where we developed and applied

the method reported in this paper.

As mentioned in above sections, we developed in

total 22 courses including training material covering

all parts of our risk-centric learning path depicted in

Figure 2. The course developers using the method

were people with different background grouped in

academia, critical infrastructure, research, and service

providers. This demonstrates the feasibility of our

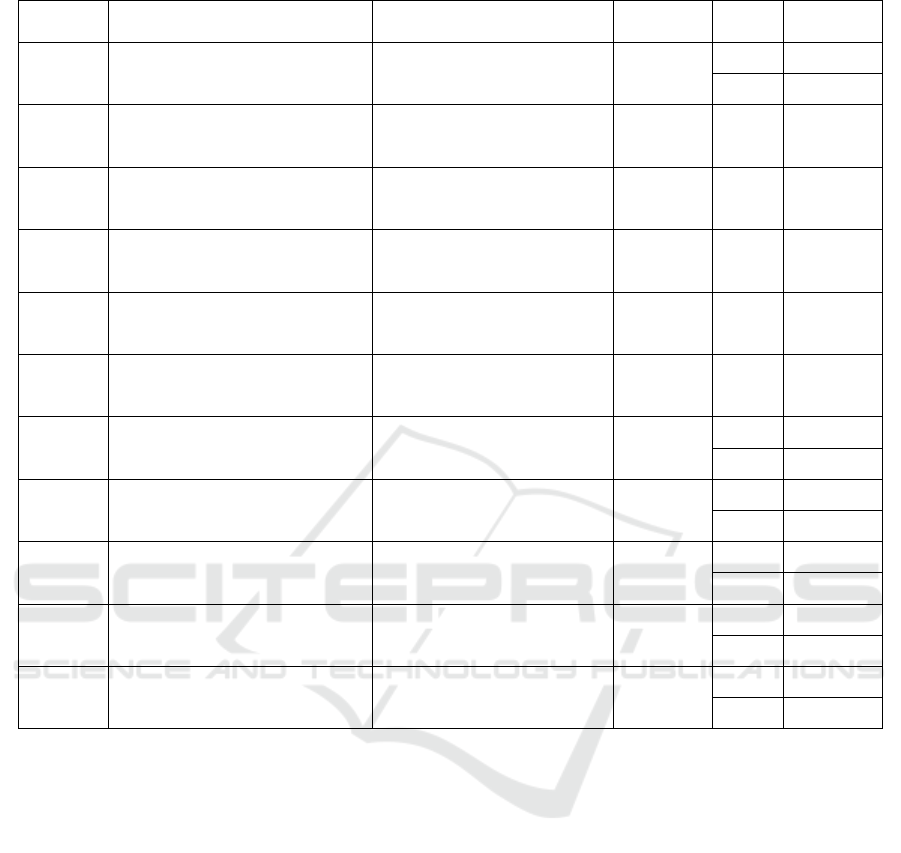

approach. Table 4 and Table 5 provide an overview of

the 22 courses we developed using our method. The

tables show the name of each course and relate the

courses to the relevant parts of the cyber-risk centric

learning path illustrated in Figure 2. We also see from

the tables the roles that are trained in each course and

the skills developed in the course. The rightmost

column of Table 4 and Table 5 shows the skill level

that is achieved for the corresponding skill after the

successful completion of the course. Note that the

courses C-02 to C-06 have no skill levels because

these courses focus on the awareness of specific

cybersecurity risks. Thus, the objective of courses C-

02 to C-06 is to make participants aware of

cybersecurity risks the society is often exposed to; not

to develop certain security skills. Section 2.3 describes

Level 1 of Skill S1, and Level 1 and 2 of Skill S2. For

a

complete descriptions of the courses, roles, skills,

Developing Cyber-risk Centric Courses and Training Material for Cyber Ranges: A Systematic Approach

709

Table 4: Courses developed using our method (C-01 to C-11).

Identifier Course Name

Activity in the cyber-risk

centric learning path

Role Skill Skill Level

C-01

Introduction to cyber-risk analysis

and cybersecurity

Cybersecurity and cyber-risk

awareness

R1, R2,

R3, R4, R5

S1 L1

S2 L1

C-02 Awareness of Phishing

Cybersecurity and cyber-risk

awareness

R1, R2,

R3, R4, R5

S1, S2,

S3

N/A

C-03

Awareness of Password

Weaknesses

Cybersecurity and cyber-risk

awareness

R1, R2,

R3, R4, R5

S1, S2,

S3

N/A

C-04 Awareness of Ransomware

Cybersecurity and cyber-risk

awareness

R1, R2,

R3, R4, R5

S1, S2,

S3

N/A

C-05 Awareness of Data Leakage

Cybersecurity and cyber-risk

awareness

R1, R2,

R3, R4, R5

S1, S2,

S3

N/A

C-06 Awareness of Insider Threat

Cybersecurity and cyber-risk

awareness

R1, R2,

R3, R4, R5

S1, S2,

S3

N/A

C-07

Introduction to cyber-risk

assessment

Cybersecurity and cyber-risk

awareness

R2, R3,

R4, R5

S1 L1

S2 L1, L2

C-08 Describe target of analysis, level 1 Context establishment

R2, R3,

R4, R5

S1 L2

S2 L2

C-09

Identify and describe security

assets, level 1

Context establishment

R2, R3,

R4, R5

S1 L2

S2 L2

C-10

Identify and describe threat

profiles and high-level risks, level

1

Context establishment

R2, R3,

R4, R5

S1 L2

S2 L2

C-11 Identify risks, level 1 Cyber-risk assessment

R2, R3,

R4, R5

S1 L2, L3

S2 L2, L3

and skill levels the reader is referred to the technical

report in which we describe the courses, roles, skills,

and skill levels in detail (Gencer Erdogan et al.,

2020b).

As part of Step 1 in our method, we aimed to

identify roles that typically conduct tasks related to

cyber-risk assessment. To make sure we are aligned

with general descriptions of security roles, we based

ourselves on well-established standards. To the best

of our knowledge, the only framework providing a set

of widely used security roles is the CIISec framework

(CIISec, 2020b, 2020c). The CIISec framework is

mainly developed to be used as a tool when

organizations are looking into recruiting certain

security roles. Alternative frameworks do exist as

pointed out in Section 2.1, but these alternatives are

mostly commercial and not easily available. Thus, an

observation worth noting is the clear need for more

open and accessible frameworks classifying and

describing cybersecurity roles to better shape the

future courses and training material in context of

cyber ranges.

However, the fact that the CIISec framework

brakes down the roles, assigns expected skills to the

roles, and provides a scale of skill levels were very

useful features to later identify learning goals and

objectives to shape courses and training material. The

scale of skills was especially useful because, as

explained in Section 2.1, the CIISec Skills

Framework provides six levels for each skill which

correspond well to the six levels of advancement

provided by Bloom's taxonomy (level 1 –

Remembering, level 2 – Understanding, level 3 –

Applying, level 4 –Analysing, level 5 – Evaluating,

and level 6 – Creating) (Anderson & Bloom, 2001).

Bloom's taxonomy is one of the most widely used

standards to describe and develop courses in general.

Moreover, based on our experience in carrying

our Step 1 of our method, we found it challenging to

make a clear distinction of the roles although we

ICISSP 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

710

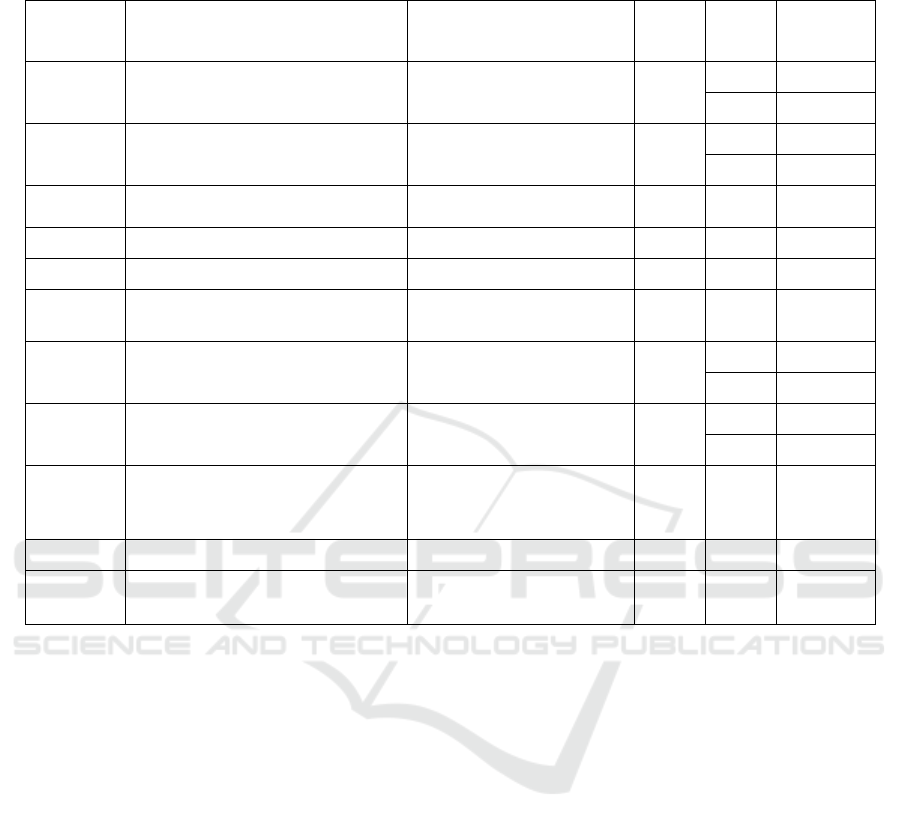

Table 5: Courses developed using our method (C-12 to C-22).

Identifier Course Name

Activity in the cyber-risk

centric learning path

Role Skill Skill Level

C-12

Awareness of Password Weakness

with hands-on training

Cybersecurity and cyber-risk

awareness

R2, R3,

R4, R5

S1 L2

S2 L2

C-13 Describe target of analysis, level 2 Context establishment R2, R3

S2 L3

S3 L3

C-14 Identify risk criteria

Context establishment,

Cybe

r

-risk assessment

R2, R3 S3 L3

C-15 Identify risks, level 2 Cyber-risk assessment R2, R3 S2 L3

C-16 Estimate risks Cyber-risk assessment R2, R3 S2 L3

C-17 Treat risks, level 1

Cyber-risk treatment and

cost/benefit analysis

R2, R3 S2 L3

C-18

Identify and describe security assets,

level 2

Context establishment

R2, R3,

R4, R5

S1 L3

S2 L3

C-19

Identify and describe threat profiles

and high-level risks, level 2

Context establishment

R2, R3,

R4, R5

S1 L3

S2 L3

C-20 Identify risks, level 3

Cyber-risk assessment,

Cyber-risk treatment and

cost/benefit analysis

R3, R4,

R5

S2 L4

C-21 Evaluate risks Cyber-risk assessment R2, R3 S2 L3

C-22 Treat risks, level 2

Cyber-risk treatment and

cost/benefit analysis

R1, R2,

R3

S2 L3

made use of descriptions provided by the CIISec

Roles Framework. This is also reflected in Tables 4

and 5 where we see that most roles are relevant for

most courses. One possible explanation is that the

descriptions of roles are too generic, but on the other

hand, having very distinct and non-overlapping roles

in practice is unlikely. Another possible explanation

could be that the courses are too generic and

approachable by many different roles. However,

looking at Tables 4 and 5, we do see that some courses

are relevant for only two or three roles, while other

courses are relevant for all roles. It is therefore

reasonable to argue that the courses are well balanced

considering the spectrum of roles identified and used

in our approach.

With respect to Step 2 of our method, Associate

the Roles and Skills to Standard Cyber-Risk

Assessment Process, we found it useful for the overall

method to associate roles to one or more phases of

cyber-risk assessment depicted in Figure 2, with

respect to the description of the roles. This helped us

to identify topics of courses for the roles and their

associated skills to train. Moreover, this showed at an

early stage the "path" a role may take to advance their

skills. Another possibility which we explored, but did

not apply, is to associate a skill directly to a phase of

cyber-risk assessment. However, the goal of our

approach is to explicitly have roles defined as the

entrance point to a set of relevant courses. We believe

this "role-based" approach to training makes it more

intuitive for participants to select appropriate training

profiles to pursue certain cybersecurity careers

corresponding to the cybersecurity roles in practice.

With respect to Step 3, Describe Courses

Considering Roles, Skills, and Risk Assessment

Process, people with different background grouped in

academia, critical infrastructure, research, and service

providers used our approach to develop the 22

courses reported in this paper. The development of

these courses was carried out using the templates in

Table 1 and Table 2. It is therefore reasonable to

argue that our approach is feasible and easy to use.

However, the course attributes related to skill and

expected skill level to be trained, learning goals, and

learning objectives in the course templates were not

trivial to define. For example, one course (such as the

one described in Table 3) could develop more than

one skill level for different roles. For example, in

Developing Cyber-risk Centric Courses and Training Material for Cyber Ranges: A Systematic Approach

711

Table 3, we see that Roles R2 and R3 develop Skill

S2 at Level 1 and 2, while Roles R4 and R5 develop

Skill S1 at Level 1. This required a detailed

understanding of each skill level and based on expert

judgment we included the skill levels to be achieved

by each role.

Regarding the description of learning goals and

learning objectives, some of the course developers

experienced initially a difficulty in distinguishing

between the two. To overcome this, we defined

learning goals as "broad learning outcomes" that may

or may not be measurable, while learning objectives

were defined as "measurable learning objectives", as

explained in Table 1.

For the template attributes mentioned above, we

experienced a somewhat steep learning curve

regarding the usage of the CIISec Skills Framework

and Bloom's Taxonomy. However, after the

development of few courses these guidelines were

easily applicable and did not cause significant

overhead when developing courses using our method.

With respect to Step 4, Develop Training Material

Based on Course Descriptions, the training materials

were developed in terms of PowerPoint presentations,

supporting literature (compendium), audio support,

questionnaires, and exam quizzes. Not surprisingly,

this step required most effort because of the time-

consuming tasks. In particular, the development of

audio support for each course was both time

consuming and required effort from several people

(narrator, sound technician, and IT personnel). It is

therefore worth looking into the cost/benefit of

having audio support in the courses presented in this

paper. However, we view this as future work.

As part of pilot exercises, 4 companies have at the

time of writing tried out some of the courses reported

in this paper. More exercises are planned with other

companies. In the following we report on two main

lessons learned that will help us shape the courses and

training materials in the future.

Participants with no prior experience in

cybersecurity reported the need for additional

theoretical lessons to be able to solve the exercises in

the courses, while participants with 1-5 years of

cybersecurity experience responded that the exercises

were too easy. Thus, when having a very wide range

of participants in terms of their skill level, it is very

difficult, if not impossible, to prepare training

material and exercises that fit all participants. It is

therefore reasonable to expect the customization of

courses depending on the target users of courses and

their skill levels.

Prior to using our cyber range platform, all

participants were expecting a basic eLearning

platform with simple questionnaires on basic

concepts and cybersecurity topics. However, they

appreciated the combination of courses and the

possibility to use hands-on attack and defence

mechanisms which was regarded as an added value to

the whole training experience. However, the effect of

audio support in the courses (positive or negative) as

mentioned above, needs to be evaluated.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Most cyber ranges do not consider learning and

educational aspects such as courses, learning goals

and learning objectives, specific skills to train and

develop, etc. We address this gap and propose a

method for developing risk-centric courses and

training material based on identified roles and skills

to be trained in cyber ranges. Our approach is cyber-

risk centric in the sense that we cluster courses, roles,

and skills with respect to steps of standard cyber-risk

assessment processes (ISO, 2018) to construct a

cyber-risk centric learning path.

Our method consists of four steps. The first step is

about identifying target-user roles and skills to train.

The identified roles and skills act as a guiding factor

throughout the method in the remaining steps, where

the goal is to produce in the last step a set of cyber-

risk centric courses and training materials. These

courses and training materials are then uploaded to

our cyber range CYBERWISER.eu ready to be used

by people to obtain cybersecurity education and skills

training for specific cybersecurity roles.

Our method has been used by people with

different background grouped in academia, critical

infrastructure, research, and service providers, who

have developed 22 courses. Some of these courses

have already been tried out in pilot studies by SMEs.

Our assessment shows that the method is feasible and

that it considers learning and educational aspects by

facilitating the systematic development of courses

and training material for specific cybersecurity roles

and skills.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been conducted as part of the

CYBERWISER.eu project (786668) funded by the

European Commission within the Horizon 2020

research and innovation programme.

ICISSP 2021 - 7th International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy

712

REFERENCES

Anderson, L. W., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for

learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of

Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives: Longman.

Ashok, A., Krishnaswamy, S., & Govindarasu, M. (2016).

PowerCyber: A remotely accessible testbed for Cyber

Physical security of the Smart Grid. Paper presented at

the 2016 IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative

Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT).

Basile, M., Varano, D., & Dini, G. (2020).

CYBERWISER.eu: Innovative Cyber Range Platform

for Cybersecurity Training in Industrial System.

Electronic Communications of the EASST, 79.

Beuran, R., Chinen, K.-i., Tan, Y., & Shinoda, Y. (2016).

Towards effective cybersecurity education and training

(IS-RR-2016-003). Retrieved from

CIISec. (2020a). Chartered Institute of Information

Security. Retrieved from

https://www.ciisec.org/Training

CIISec. (2020b). CIISec Roles Framework, Version 0.3,

November 2019. Retrieved from

https://www.ciisec.org/

CIISec. (2020c). CIISec Skills Framework, Version 2.4,

November 2019. Retrieved from

https://www.ciisec.org/

CMU. (2020). STEPfwd - A Cyber Workforce Research

and Development Platform CERT STEPfwd. Retrieved

from https://stepfwd.cert.org/lms

CYBERWISER.eu. (2020). CYBERWISER.eu - Cyber

Range & Capacity Building in Cybersecurity. Retrieved

from https://www.cyberwiser.eu/

Damodaran, S. K., & Smith, K. (2015). CRIS Cyber Range

Lexicon, Version 1.0. Retrieved from

https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a627477.pdf

Davis, J., & Magrath, S. (2013). A survey of cyber ranges

and testbeds. Retrieved from

https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a594524.pdf

EnpitSecurity. (2020). SecCap. Retrieved from

https://www.seccap.jp/

Erdogan, G., Hugo, Å., Romero, A. Á., Varano, D., Zazzeri,

N., & Žitnik, A. (2020a). An Approach to Train and

Evaluate the Cybersecurity Skills of Participants in

Cyber Ranges based on Cyber-Risk Models. Paper

presented at the 15th International Conference on

Software Technologies.

Erdogan, G., Tverdal, S., Hugo, Å., Omerovic, A., Stølen,

K., Varano, D., . . . Mancarella, C. (2020b). D4.4

Training material, final version. Retrieved from

https://www.cyberwiser.eu/content/d44training-

material-final-version

Ferguson, B., Tall, A., & Olsen, D. (2014). National cyber

range overview. Paper presented at the 2014 IEEE

Military Communications Conference.

ISO. (2018). ISO/IEC 27005:2018(en) Information

technology — Security techniques — Information

security risk management. In.

MITRE. (2020). The MITRE Corporation. Retrieved from

https://www.mitre.org/

NRISecure. (2020). Secure Eggs (Essentials and Global

Guidance for Security). Retrieved from

https://www.nri-

secure.co.jp/service/learning/secureeggs

OWASP. (2020). The Open Web Application Security

Project. Retrieved from https://owasp.org/

Pfrang, S., Kippe, J., Meier, D., & Haas, C. (2016). Design

and architecture of an industrial it security lab. Paper

presented at the International Conference on Testbeds

and Research Infrastructures.

Pham, C., Tang, D., Chinen, K.-i., & Beuran, R. (2016).

Cyris: A cyber range instantiation system for

facilitating security training.

Paper presented at the

Seventh Symposium on Information and

Communication Technology.

SANS. (2020). The SANS Institute. Retrieved from

https://www.sans.org/about/

Somarakis, I., Smyrlis, M., Fysarakis, K., & Spanoudakis,

G. (2019). Model-Driven Cyber Range Training: A

Cyber Security Assurance Perspective. In Computer

Security (pp. 172-184): Springer.

Yamin, M. M., Katt, B., & Gkioulos, V. (2020). Cyber

Ranges and Security Testbeds: Scenarios, Functions,

Tools and Architecture. Computers & Security, 88,

101636.

Developing Cyber-risk Centric Courses and Training Material for Cyber Ranges: A Systematic Approach

713