Investigating the Impediments to Accessing Reliable, Timely and

Integrated Electronic Patient Data in Healthcare Sites in Uganda

Andrew Egwar Alunyu

1,2 a

, Joseph Wamema

2b

, Achilles Kiwanuka

2c

, Bagyendera Moses

2

,

Mercy Amiyo

2d

, Andrew Kambugu

3e

and Josephine Nabukenya

2f

1

Department of Computer Engineering, Busitema University, Tororo, Uganda

2

Department of Information Systems, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

3

Infectious Disease Institute, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda

Keywords: Data Accessibility and Reliability, Electronic Health Information Systems, Integrated Patient Data.

Abstract: The purpose of collecting patient data is to support their care and wellbeing. Patient-centred care is attained

by securely availing all records about the patient whenever it's necessary to the right persons and at the right

time. However, healthcare providers have often failed to share integrated patient data on time due to

limitations in accessing reliable patient data required to inform care/treatment decisions. This study aimed to

investigate impediments to accessing reliable, timely and integrated patient data through investigating the

processes for collection, analysis, and presentation of data across various healthcare sites in Uganda. A cross-

sectional study design was followed, and data was collected from purposively selected National level

(policymakers) and Sub-national level (health facilities). The field findings indicate various impediments to

accessing patient data including but not limited to inadequate mechanisms for electronic health data collection,

storage and access, non-standardised health data sharing mechanisms, inadequate Health Information System

(HIS) and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) infrastructure, and inadequate skills,

knowledge and training. Other impediments included; insufficient security and privacy measures, weak

eHealth governance, and inadequate management support. Accordingly, these have negatively impacted on

patient data use and quality of patient care in Uganda.

1 INTRODUCTION

Governments in lower-middle and low-income

countries like Uganda have adopted the use of ICT to

improve the delivery of services including healthcare

to all its citizens. Uganda’s eHealth Policy and

Strategy documents have identified unique pillars

necessary to support the successful adoption of ICT

to support healthcare (Ministry of Health, Uganda,

2016). However, reaping the benefits of ICT in

healthcare have continued to face a lot of challenges

including; lack of specific standards on electronic

data collection, storage and sharing, non-

interoperable ICT systems and technologies,

resistance to using ICT to support healthcare, limited

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2957-8423

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6328-7801

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3352-0312

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8172-5382

e

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3075-0211

f

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4731-2496

ICT skills and knowledge as well as weak governance

structures ( Ministry of Health, Uganda, 2016; Ross

et al., 2016; Sara, 2016).

These ICT challenges often impact the collection,

sharing, storage, and use of patient data. Patient data

is collected “to create holistic views of patients,

personalize treatments, advance treatment methods,

improve communication between doctors and

patients, and enhance health outcomes”(Sakovich,

2019). To have a complete history of a patient, there

is a need for all medical records/ data to be availed in

an integrated and reliable manner. However,

healthcare providers have often failed to access

patient data on time, even though patient-centred care

requires that all data about a patient is made available

522

Alunyu, A., Wamema, J., Kiwanuka, A., Moses, B., Amiyo, M., Kambugu, A. and Nabukenya, J.

Investigating the Impediments to Accessing Reliable, Timely and Integrated Electronic Patient Data in Healthcare Sites in Uganda.

DOI: 10.5220/0010266705220532

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2021) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 522-532

ISBN: 978-989-758-490-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

on time (Kuipers et al., 2019). Any delay to access a

patient’s data resulting from technology, access rights

or even lack of integration may lead to loss of life.

Besides, patient data may be captured/stored on

different geographically placed eHealth systems. Any

lack of integration of patient data fetched from such

systems may negatively impact healthcare.

Patient care involves the participation of various

stakeholders including healthcare practitioners who

provide care, healthcare organisations who

participate in patient care, decision-makers in

government, the patient’s caretakers and the patients

themselves. Patient data is required by any of them,

anywhere, anytime; thus, the need for integration and

timely access as any delay or lack of integration

would hamper proper care of the patient.

To gain an insight into impediments to accessing

reliable, timely and integrated electronic patient data

in lower-middle and low-income countries. This

study investigated Uganda’s healthcare sites with a

specific focus on the processes for collection,

analysis, and presentation of patient data.

2 METHODS

The study followed a cross-sectional design. The

cross-sectional design provides a snapshot of the

prevalence of the study subjects in a single time point

(Awaisu, et al., 2019).

Sampling Method: Purposive sampling was used

to select both study sites and participants of this

study. The decision to use purposive sampling was

motivated by its ability to support the identification

of all cases that meet a predetermined criterion of

importance (Palinkas et al., 2015) as described below:

Inclusion Criteria for Study Sites: This study

mainly focused on the HIV/TB disease domain of

Uganda’s healthcare system. The HIV/TB disease

domain was adopted because of the heavy reliance on

eHealth systems (i.e Integrated Clinic Enterprise

Application (ICEA) and OpenMRS/UgandaEMR) to

deliver services to clients (Castelnuovo et al., 2012).

Both national and sub-national level health

institutions were used in this study. At subnational

level, 28 health facilities were chosen to participate in

the study. A health facility was chosen as a study site

if it was among the top four health system levels in

Uganda, i.e., National Referral Hospital (NRH),

Regional Referral Hospital (RRH), District Hospital

(DH), and Health Center Fours (HC IVs); and also, if

it was in the Northern, North-Western, Western or

Central regions of Uganda. These regions were

chosen on grounds that they have a high prevalence

of HIV/TB (Ministry of Health, Uganda, 2017)

characterised by high mobility, slum-dwelling, and

limited social support (Central Uganda), urban/rural

populations undergoing significant socio-economic

transformation with an influx of high-risk groups for

HIV transmission (Mid-Western Uganda), low-

prevalence, sparsely populated area but prone to the

influx of refugees .and or internal displacement (West

Nile and Northern regions of Uganda) Additionally,

the sites were chosen if they had adopted and

implemented eHealth systems of some nature. Lastly,

if the site was an Infectious Disease Institute (IDI)

site. Makerere University IDI is a major partner in the

implementation of HIV in Uganda and possess

experience in transitioning from paper-based to

eHealth systems (Castelnuovo et al., 2012). Also, 11

government Ministries, Departments, and Agencies

(MDAs), healthcare organisations, and eHealth

stakeholders like academia, developers and

implementers were included in the study. These were

chosen on the basis that they participated in the

development of the national eHealth strategy/policy

for Uganda, undertaken research in eHealth,

developed/invested in electronic health systems,

implemented electronic health systems among others.

Overall, the study sample size of this study was 196

possible responses from subnational level and 34

respondents from national level.

Inclusion Criteria for Participants: Participants

at health facility level were chosen if they were

officers-in-charge of a health facility,

ICT/Data/Records/M&E Officers, or users of eHealth

in the categories of Clinical Officers, Nurses,

Pharmacist, and Laboratory Technologist.

Participants at the national level were chosen if they

were eHealth Policy Makers, standard/guideline

developers, Health Implementation Partners, Health

Systems and Health Informatics researchers. Only

potential participants who consented to participate in

the study were finally interviewed.

Ethical Consideration: The researchers obtained

consent to assess the study sites from the Ministry of

Health. Ethical clearance was also obtained from the

Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the School of

Public Health, Makerere University.

Data Collection Tools: To obtain representative

views from facility-level and national-level

participants, the study used both interviews and

questionnaires to collect data. Whereas the

questionnaires helped to discover what the eHealth

stakeholders (the masses) think about timely, reliable

and integrated access to patient data; follow-up

interviews were conducted to further authenticate

and/or corroborate their responses (Cohen, 2013).

Investigating the Impediments to Accessing Reliable, Timely and Integrated Electronic Patient Data in Healthcare Sites in Uganda

523

Data Analysis: To analyse quantitative data (i.e.

data collected at the facility level), the researchers

used MS Excel software. Quantitative analysis was

performed to explore the relationships in the collected

data. The results of the quantitative analysis are

presented either statistically or graphically to show

the status quo regarding impediments to accessing

reliable, timely and integrated patient data. The

qualitative data (i.e. majorly collected at national

level) was analysed following the framework method

(Gale et al., 2013). The framework method allowed

the researchers to develop codes, use and categorise

the codes into themes. NVivo 12 was used to assist

and aid the researchers to code and organise the

qualitative data into themes and evidence on

impediments to accessing reliable, timely and

integrated patient data in Uganda.

3 RESULTS

Results of this study are based on 201 responses from

obtained from sub-national and national levels. The

sub-national level response was highest among nurses

(26%) who are the majority users of the ICT,

followed by medical officers (15%), laboratory

(14%), pharmacy (13%), officers-in-charge of health

facilities (11%). Response at the national level is

represented by 6% being health systems and health

informatics researchers, 4% were policymakers from

Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs), and

3% being the Healthcare Development Partners

(HDPs) in Uganda.

Subsequent subsections present the findings

categorized under the three broad themes of

technology-related impediments, inadequate user

skills, knowledge and training on eHealth, and

healthcare organizational environment.

3.1 Technology-related Impediments

a) Mechanisms for Data Handling

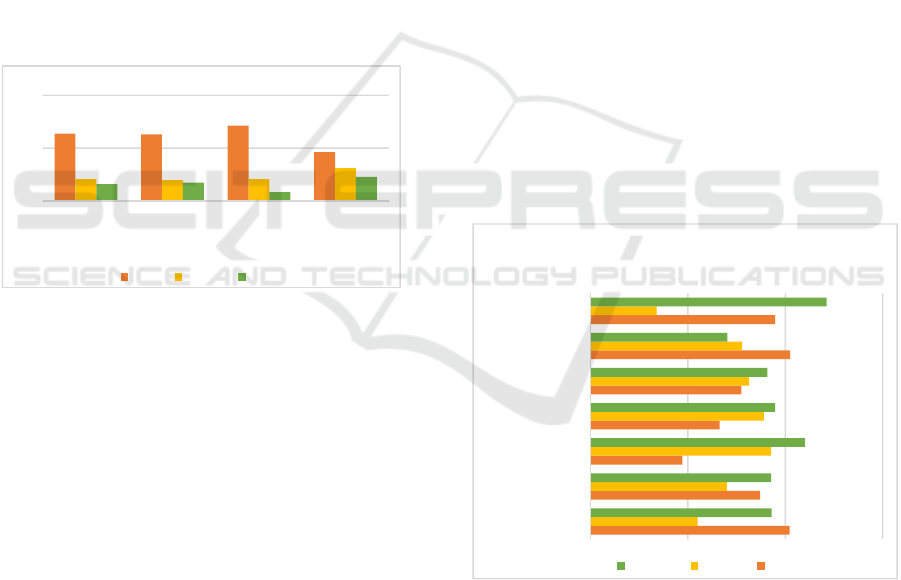

Figure 1 shows the views of respondents regarding

the handling (i.e., collection, storage and access) of

patient data at various health facilities across the four

regions that were studied. The responses relate to how

patient data handling processes at health facilities

affect its timely access, reliability and integration.

Limited Training in Electronic Health Data

Classification: On the classification of health data,

81.1% of the respondents agreed that they do classify

the health data during its collection. Much as the

majority of the respondents agreed to classifying

health data during collection, only 40.9% reported

that they had been trained on health data

classification, an indication that they had limited

training in health data classification as expressed by

respondent HSL4-25 … “For me, I was not trained in

coding but I had to learn from a colleague who was

trained by ministry officials.” Lack of proper training

in the classification of health data can affect its

reliability and integration since data collectors are

likely to use different classification codes. When

respondents were asked what challenges were faced

in classifying the health data during its collection,

changing of indicator definitions was mentioned as

the key challenge. In an interview, a respondent said:

“The challenge that we have is that the indicators are

usually changing. You find even the indicators that

are national keep on changing. For example, the

HMIS tools have been revised. We have to be so

adaptive to all the new changes and train people

again. When the staff have just learnt how to capture

the data, new indicators are put in place and so more

training is needed on the new indicators” - HSL2-06.

While another respondent felt the impact of changing

indicators’ definitions as expressed: “Since many of

the tools we use are routinely revised. You find that

the data that was stored five years ago is different

from the data that is currently stored because of the

new indicators. If they add new indictors, they bring

along new registers. Therefore, I am asked to train

the staff on the new registers”- HSL3-01.

Figure 1: Views on Health Data Handling.

Use of Paper-based Data Storage Mechanisms:

To gain an insight into how health data was stored at

respective health facilities, majority of the

respondents (84.8%) reported that this was done. Our

findings indicate that most of the health data was

stored manually (paper-based files), and most times

were incomplete as reported by one respondent:

“Most of our data is in manual files so we keep the

files in the records office that you see there. Some are

incomplete, others are misplaced. They always

81.1

40.9

84.8

78.8

9.8

19.7

10.6

12.1

9.1

39.4

4.5

9.1

Health data is

classified

Adequate

training on

health data

classification

Health data

from the health

facility is

archived

I access

patient’s data

in a timely

manner

Percentage of Respondents (%)

Health data Collection, Storage and Access

(Data Management)

Agree Neutral Disagree

HEALTHINF 2021 - 14th International Conference on Health Informatics

524

present it to us as senior management on every

Thursday but you see a lot of gaps in them when they

are presenting”- HSL2-02.

On how to access the data stored in manual files,

a respondent indicated that it was a tedious exercise

requiring one to go through all the shelves to locate a

file that had a record of interest. A respondent had this

to say: “Filing is one of the trick works. Sometimes,

once in a while someone can interchange the position

of the file and you want to retrieve and you cannot see

it. Maybe by mistake it has been twisted and it has

missed its position. That can make the file a little bit

difficult to be traced.”-HSL4-25. Such a response

evidenced use of poor mechanisms to store health

data, impacting its timely access as well as reliability.

Untimely Access to Health Data: To understand

how well health data is managed at the health

facilities, respondents were asked whether they had

timely access to patients’ data. 78.8% agreed they do.

However, some complained about delay in accessing

patient data as commented by this respondent: “The

only challenge to data access is the workload of the

person who has the data that you need. You may find

that that person has too much work and cannot give

you the data at the time that you need it. You go and

find someone doing other things and may postpone

the time you may access data” – HSL2-04.

b) Non-standardised Health Data Sharing

Mechanisms

To gain an insight into the data-sharing challenges,

this study investigated issues on the guidelines/SOPs

for sharing health data, and how this data was shared

both within and with other health facilities (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mechanisms for Health Data Sharing.

Existence of Guidelines/SOPs for Sharing

Electronic Health Data: On the existence of

guidelines and/or Standard Operating Procedures

(SOPs) for sharing health data, 64.4% agreed to

existence of guidelines/SOPs for data sharing. The

majority of the respondents who agreed to the

existence of guidelines/SOPs for sharing health data

might not have referred specifically to the use of ICT

to share data, rather to the general guidelines for

health data sharing and exchange such as the data

protection policy, as evidenced by some respondents

who said; as an institution, we have a data protection

policy that guides all staff that are accessing data and

other records” – IP06; “what I know is that data is

confidential and if you are sharing you need to share

with only health workers” – HSL4-26; “There is no

comprehensive SOP” – HSL3-02. However, some

respondents indicated that though their facilities had

SOPs for data sharing, these were not comprehensive

enough and that some had been locally made as

reported by respondents: “There is no comprehensive

SOP” - HSL3-02; “the health sector is sensitive and

you cannot come up with your own SOP and yet

“some of them are locally made”- HSL2-06.

On the issue of guidelines for accessing EMRs,

the respondents had mixed opinions. While 31.8% of

the respondents agreed to the existence of guidelines

for EMR, 42.4% were neutral and 25.8% disagreed.

The respondents who agreed to the existence of the

standards to access EMRs could not provide copies of

such standards as we observed: “It’s not documented

but we know about them”-HSL4-26.

On data sharing within a health facility, 84.8%

agreed that health data was shared. The respondents

who agreed to share data intra-facility referred to the

paper-based mechanism to share health records. For

example, when asked whether they used ICTs to share

health data with another ward or physician within the

health facility, a respondent said: “currently we have

not been using ICT, but we are hoping that it will be

there” – HSL3-06.

On data sharing with other health facilities, 56.1%

of respondents agreed that they do. However, from

the interviews, it was noted that the current nature of

shared data mainly constituted national, monthly and

quarterly reports as evidenced by one respondent who

said: “The information we generate from here is

entered into the District Health Information System

and from there it is transmitted to the ministry. The

partners also use the same system to get their share,

their part of the information. But, at the same time

like for the partners, they come up to the primary

source of the data, they pick it also and then they

compare with what the facility has sent” – HSL4-11.

As much as patient data was shared both within

and outside the health facility, there seemed to be no

agreed mechanism for sharing this health data as

indicated by a respondent in an interview: “We have

to use other things. So, you have to use like WhatsApp

and Facebook, those others, not the government

systems, not the Uganda health system” – HSL4-20.

64.4

31.8

84.8

56.1

19.7

42.4

8.3

13.6

15.9

25.8

6.8

30.3

There is SOP for

moving data

Facility has

guidelines for

accessing EMRs

Intra-Facility

HIE

Inter-Facility

HIE

Percentage of Respondents

(%)

Health Data Sharing

Agree Neutral Disagree

Investigating the Impediments to Accessing Reliable, Timely and Integrated Electronic Patient Data in Healthcare Sites in Uganda

525

c) Insufficient Electronic Health Data Security

and Privacy Measures

The study also investigated the existence of measures

for security and privacy of health data at the health

facilities (that is, safeguards to health data as well as

personally identifiable data as seen in Figure 3). On

the issue of safeguards to health data, 63.6% of

respondents agreed that security measures/controls

had been implemented at the health facilities. This

high percentage could have referred to physical

access to health data storage facilities including ICTs.

In an interview, respondents had this to say: “Physical

security is key, the server environment is secured,

locked with only fingerprint access” - IP03. “specific

people who are using this machine. It’s not everybody

who accesses it and even we lock also the computers

and even as I told you we have the security guards we

have two that makes our information safe” – HSL4-

18. “Not everyone enters the records room. All the

cabinets are lockable” – HSL4-22.

Figure 3: Data Security and Privacy Measures.

On whether security controls had been

implemented in the ICTs that are used at the health

facilities, 62.9% agreed that this had been done.

Respondents could have interpreted security to mean

the presence of passwords that are used to access

computers as evidenced by the interview responses:

“There is a password in this EMR. A person who is

logging in is given account so you log in using their

account. And the account is not given to all. And the

access right is not given to all the people”-HSL4-13;

“Here like on my computer, we have password that

not everyone has access to”-HSL3-03; and “In

softcopies there is passwords which I normally put

there and people cannot access the data”-HSF4-18.

However, only 46.2% agreed that information

security controls were sufficient. Those who

disagreed (22.7%) or were neutral (31.1%) could

have represented respondents from health facilities

where security breaches had been experienced. From

the interviews, respondents said; “we have

experienced theft of computers like regional referral

in October they lost about ten computers.” - HSL4-

25; “Yes, some thieves have ever broken in the

facility, although the computers were recovered. if

his place can be faced maybe the issue of security

would be solved and also we might need more

security guards to guard the facility”-HSL4-30.

Concerning personally identifiable data, 71.2% of

respondents agreed that this data is hidden which is

an indication that measures to ensure the privacy of

personally identifiable data had been implemented.

This high percentage of respondents who agreed

could be attributed to the need to protect information

as confirmed by 80.3% of respondents who said that

the health data they collect is valuable.

d) Inadequate HIS and ICT Infrastructure

Respondents were asked to give their views on the

suitability of existing HISs and supporting

infrastructure in Uganda’s top four health system

levels to deliver access to quality and timely health

data. The questions asked related to the relevance of

the applications to support healthcare work routines,

use of eHealth applications and/or technologies,

characteristics that make the application suitable, and

technology infrastructure to support access to

patients’ data in a reliable, timely, and integrated

manner (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Characteristics of eHealth applications/

technologies used in healthcare facilities.

Apprehension to using ICT in Healthcare:

Results show that although a majority of the

respondents agreed on the compatibility of existing

technologies with work routines (40.9%) and ability

of eHealth applications to enhance productivity

(41%); they disagreed or remained neutral on the rest

63.6

62.9

71.2

46.2

20.5

19.7

20.5

31.1

15.9

17.4

8.4

22.7

Security

controls are

implemented

Existing ICTs

are secure and

privy

Personal

identifiable

data is hidden

Security

controls are

sufficient

Percentage of Respondents

(%)

Data Security and Privacy

Agree Neutral Disagree

40.9

34.8

18.9

26.5

31

41

37.9

22

28

37.1

35.6

32.6

31.1

13.6

37.2

37.1

44

37.9

36.3

28.1

48.5

Compartibility with

work routines

Easy to Learn

Erro Free

App is Intergratble

App provides

Relevant Data

App enhances

Productivity

Adequate ICT

Infrastacture

Percentage of Respondents (%)

Characteristics of eHealth

Applications/Technologies currently used to

support healthcare services in Uganda

Disagree Neutral Agree

HEALTHINF 2021 - 14th International Conference on Health Informatics

526

of the characteristics indicative of existing

apprehension/challenges to using ICT in healthcare.

Insufficient Training in the use of eHealth

Applications/Technologies: On the question of

whether the eHealth applications that they used were

easy to learn, respondents had mixed reactions with

34.8% in agreement, 28% neutral and 37.1%

disagreed. The negative responses concerning the

ease of use of the eHealth applications could have

been a result of the varied training capacities, that is,

while some were trained by the funders/investors,

others did not receive any training as evidenced from

the interview responses; “We are given the system

with the database and they are national. We are

trained on how to use it” – HSL4-24; on the contrary,

a respondent said: “No I just trained myself” – HSL4-

08; while another respondent said: “All those who

work on these computers struggle with some few days

of training, say like in Uganda EMR” – HSL3-05.

Characteristics of the HIS Applications that are

used: Respondents were asked to give their opinions

on the characteristics of the eHealth applications that

they use. On whether the applications were error-free,

only 18.8% agreed. This meant that the reliability of

the applications' data could be queried. This could be

the reason 37.1% disagreed with the relevancy of data

provided by these eHealth / HIS applications.

When asked whether the eHealth applications

used within the health facilities can integrate with

other eHealth applications outside of the health

facilities, there were mixed responses; 37.9% of

respondents disagreed, 35.6% remained neutral, and

26.5%agreed. Those who remained neutral and

disagreed may represent respondents that had a

limited understanding of the functionalities of the

eHealth applications that were being used at the

health facilities. Generally, the respondents did not

commit to the suitability of the eHealth applications

that they used to access health data on time. In one of

the respondents’ own words he said: “I would

actually recommend that if there is need to introduce

any other system, it should be a system that is safe,

effective, fast which can help us access what we need

in a timely manner. If we can at least get a system

which is quick, effective and convenient with no

interruptions, it would be better” – HSL2-04.

Poor eHealth Infrastructure: On whether the

health facilities had adequate eHealth infrastructure

to support timely access to patient data, 48.5% of

respondents reported that hardware and application

technologies that support eHealth were not sufficient

to support healthcare processes that relate to

collection and analysis of health data. The

respondents’ views ranged from inadequate ICT

devices e.g. “lack of enough systems in place like the

workstations. You find you may have like 3 computers

to serve all this large number of 12000 clients.” –

HSL2-04); poor electric power e.g. “we have power

challenges. we find that at times there is power

fluctuation and our backups at times are not so

reliable. We have a backup generator but at times

there is no fuel.” – HSL2-06); poor maintenance e.g.

“The few gadgets around have a challenge of

maintenance costs and so maintenance being a

problem” -HSL4-32); and intermittent network

connectivity and/or lack of mobile data e.g., “The

challenge I have experienced for a while has been

internet connectivity. Sometimes you are supposed to

send reports when there is no data on the modem” –

HSL2-01) among others.

3.2 Inadequate Skills, Knowledge and

Training on eHealth

This study also sought for respondents’ views on the

expertise, confidence and training on using eHealth

(Figure 5). On confidence and control when using

eHealth, only 31.1% of respondents agreed that they

were confident when using eHealth applications. The

low percentage of respondents who agreed to be

confident when using eHealth may be attributed to

limited experience and expertise in eHealth usage.

Less than half (42.4%) of respondents agreed that

they had experience and expertise in using eHealth.

The low percentage of those who agreed that they had

experience and expertise in the use of eHealth may

also be attributed to insufficient training (52.3%), as

evidenced by some respondents: “… challenge is the

human resource. They are yet to train our people to

know how to use it” – HSL2-02; “it is a new system

which has come up. You know it comes with some

challenges if one is having a knowledge gap” –

HSL2-05; and “ICT skills are inadequate/lacking

among healthcare workers”– RI01.

Figure 5: Capacity in using eHealth Applications/

Technologies in Healthcare Processes.

42.4

31.1

28

23.5

25.8

19.7

34.1

43.2

52.3

Adequate expertise in

eHealth

Confidence & control

using eHealth

application

Trained to use the

eHealth application

Percentage of Respondents

(%)

Use skills and knowledge

Agree Neutral Disagree

Investigating the Impediments to Accessing Reliable, Timely and Integrated Electronic Patient Data in Healthcare Sites in Uganda

527

The limitations of user skills and knowledge by

health practitioners may be a result of failure to

incorporate ICT skills in most of the curriculum of

healthcare professionals as mentioned by some

respondents who said: “inadequate integration of

eHealth skills into existing health professional

training curricula”-IP04; and “Not everyone in the

ART clinic is computer literate. It is only the health

information assistant who is well trained in computer

skills” – HSL4-15. Some universities and tertiary

institutions have however started training healthcare

professionals in ICTs skills as mentioned by a

respondent: “ICT skills related to eHealth are

inadequate, both in terms of the numbers and skills

mix/set. However, situation though is much better

now than it was 5 years or more ago. Some training

institutions has trained healthcare professionals who

understand ICT” - IP04.

3.3 Healthcare Organizational

Environment

To further understand how the healthcare

environment can impact on access to reliable, timely,

and integrated data, this study also investigated the

governance factors including governance of ICT for

healthcare and management support for the

implementation and operation of eHealth (Figure 6).

Figure 6: eHealth governance factors that affect eHealth

data management.

Weak eHealth Governance - On the governance

of eHealth, this study mainly focused on planning for

eHealth, coordination of eHealth implementation and

compliance monitoring. The majority of the

respondents (52.3%) reported that management is

involved in the preparation of eHealth

implementation plans and that there is coordination

with implementation agencies (60.6%). These

findings indicate that there is some kind of framework

that is followed to govern the implementation of

eHealth in Uganda. However, our findings indicate

that the framework has not yet been documented as

evidenced by one respondent: “let’s say there is a

framework but at the time we developed ICEA, it

wasn’t necessarily written down. It’s just that we all

knew that the system we wanted to develop would

address the institutions need, the funders need, and

the MOH requirement. So that was the framework,

but that framework was in our mind, I don’t think it

was explicitly laid down somewhere at that time”-

IP05. Lack of a well-documented implementation

framework was further echoed by respondents:

“There are insufficient governance structures to

guide the development of eHealth across the health

sector” –R101; and that “There is insufficient

coordination and participation of partners in public-

private-partnerships in promoting ICT in the health

sector”-PM04.

On the existence of monitoring structures, 34.8%

agreed, 37.1% remained neutral and 28% disagreed.

Also, on monitoring compliance with ICT guidelines,

30.3% agreed that this is done, 35.6% remained

neutral, while 34.1% disagreed. These results show

that a higher number of respondents remained neutral

on the existence of monitoring structures as well as

compliance with ICT guidelines. This may signify the

lack of awareness of eHealth governance structures at

the health facilities level. It is evident by the fact that

despite more respondents agreeing on the existence of

monitoring structure (34.8%), a significant number

said it is not monitored (34.1%). Most users of

eHealth comply because it is mandatory; however,

with “limited/lack of a monitoring system in place” –

RI01, the compliance is compromised.

Inadequate Management Support - Results

from this study (Figure 7) show that management at

the health facilities provides resources and support for

use of the eHealth (50.7%). This may be attributed to

the management’s awareness of the benefits of

eHealth (69.7%). Support for eHealth by

management was echoed by some respondents as

evidenced in their own words: “Management, their

level has done best to ensure that possible request has

been met in terms of the ICT tools. The computers and

these all come through them” – HSL2-01;

“Management has always been supportive in the use

of electronic systems, electronic data. How are they

supportive? Right now, if you can see there is a lot of

investment being done in purchase of these electronic

systems” – HSL3-01; and “The management has

helped us in funding our trainings, when we have

been called for training because the training focus on

the use of the software system or the software we have

been using for the medical management”-HSL2-01.

52.3

60.6

34.8

30.3

28.8

20.5

37.1

35.6

18.9

18.9

28

34.1

Mgt prepares

eHealth

implemention

plan

Coordination by

implementing

agencies

A monitoring

structure exists

Compliance

with ICT

guidelines is

monitored

Percentage of Respondents

(%)

eHealth Governance

Agree Neutral Disagree

HEALTHINF 2021 - 14th International Conference on Health Informatics

528

Figure 7: Role of Management to Support Implementation

and Use of eHealth Applications.

These responses could mean that there is suitable

eHealth implementation and its use; however, gaps

remain as only 42.4% agreed that management

effectively address eHealth applications challenges.

Although 60.6% of respondents agreed that there

were good communication and coordination among

eHealth implementing agencies, 18.9% disagreed.

The few who disagreed argued that there is still

“insufficient coordination and participation of

partners in public-private-partnerships in promoting

ICT in the health sector”-PM04. The limitation in

communication and or coordination may be attributed

to governance factors including structures to oversee

implementation and compliance to standards as

reported by some respondents: “Insufficient

governance structures to guide the development of

eHealth across the health sector” – PM04;

“Limited/lack of monitoring system in place” – RI01;

and “I believe the regulatory framework is still in its

infancy stage and therefore generally still lacking; it

needs to become better developed, coordinated and

enforced” – IP07.

4 DISCUSSION

In Uganda, we observed that numerous EMR-based

electronic Health Information Systems(eHIS)

initiatives including OpenMRS/ UgandaEMR, ICEA,

DHIS2, OptionB+ were being used in the

management of HIV and TB patients (Ministry of

Health, Uganda, 2016). Despite their existence, our

findings evidence various impediments to accessing

reliable, timely and integrated patient data from

existing eHIS as discussed below:

Insufficient Mechanisms for the Collection,

Storage and Access to Electronic Health Data –

Collecting healthcare data generated across a variety

of sources encourages efficient communication

between doctors and patients, and increases the

overall quality of patient care providing deeper

insights into specific conditions. The way health data

is collected and stored has a bearing on its access,

reliability and ability to integrate. For example,

“during the move from a paper record or from one

computerized system to another, records can be

misplaced or incorrectly added to a patient’s record”

(Rodziewicz & Hipskind, 2020) affecting the

reliability of the patient data. The study identified

limited training in electronic health data classification

and use of paper-based data storage mechanisms as

specific impediments to the process of electronic data

handling in Uganda’s health system affecting

integrated and timely access to patient data across

health facilities. Therefore, first-line eHealth

technology users (data collectors) and the

eHISs/applications or technologies need to capture,

process and present accurate data.

Inadequate and Unsuitable HIS and ICT

Infrastructure – eHealth has been recognized to

have tremendous potential for managing patient

health data (Barello et al., 2016). eHIS and/or

applications allow the development of reliable and

integrated patient data and promote effective

exchanges among the actors involved in the

healthcare process (Khubone et al.,2020). However,

existing eHealth applications have errors, lack useful

data, and cannot be easily integrated with data from

other applications. This is a design-reality gap.

eHealth success or failure largely depends on the size

of the gap that exists between current realities and the

design of the application (Anthopoulos et al., 2016;

Ishijima et al., 2015) which user-centred participatory

design can remedy (Williams & Coles-Kemp, 2014).

Also, facilitating infrastructure should be

adequate to support capture, analysis, storage, sharing

and presentation of health data (Aanestad et al.,

2017). However, findings revealed few and poorly

maintained infrastructural resources that may be slow

and unable to support the timely and integrated

sharing of health data. Current modes of health data

communication include the sharing of text, images,

audio, and video (Al-Safadi, 2016) requiring the

supporting eHealth infrastructure to be fast, flexible,

large, reliable and with appropriate security and

privacy measures (Aanestad et al., 2017). The poor

state of the eHealth applications and infrastructure

could have led to apprehension among some of the

target users of eHealth in Uganda to use ICT in

46.3

60.6

50.7

42.4

69.7

25

20.5

25.8

31.1

20.5

28.8

18.9

23.4

26.6

9.8

There is strong eHealth governance at

the health facility

There is good communication and

coordination among eHealth

implementing agencies

Management provides necessary

resources and support for use eHealth

Management effectively address

emerging challenges to eHealth

application

Management is aware of the benefits of

eHealth

Percentage of Respondents (%)

Role of Management

Disagree Neutral Agree

Investigating the Impediments to Accessing Reliable, Timely and Integrated Electronic Patient Data in Healthcare Sites in Uganda

529

support of healthcare processes contributing

additional challenges to timely access to patient data

(Ministry of Health, Uganda, 2016).

Inadequate eHealth Skills and Knowledge –

although eHealth has become an integrated part of

modern healthcare (Bedeley & Palvia, 2014; Gregory

& Tembo, 2017), a range of individuals within

healthcare experience challenges of using and

benefiting from the technology (Furstrand & Kayser,

2015). For eHealth to be valuable in providing timely,

accessible and integrated health data, users must have

the necessary skills and understanding (Standing &

Cripps, 2015). However, this study showed that there

was a lack of sufficient skills and knowledge to use

eHealth applications as represented by 52.3 % who

claimed that they were not trained in the use of

eHealth. Without proper skills and knowledge,

healthcare providers are likely to find difficulty in

accessing healthcare information to make good

medical decisions (Hoque et al., 2014). Availability

of a skilled workforce that understands healthcare and

ICT is a critical success factor (Standing & Cripps,

2015). That can be achieved through training and

demonstrating the benefits of eHealth (Alunyu et al.,

2020; Hoque et al., 2014; Were et al., 2015).

Insufficient Electronic Health Data Security

and Privacy Measures – The study findings show

three broad security and privacy concerns, i.e.,

limited understanding of ICT security and privacy

measures, lack of policies specific to security and

privacy of health data, and full implementation and

enforcement of security and privacy measures to

include both physical and electronic security. The

right of individual patients to nondisclosure of their

health information (privacy) and mechanisms in place

to protect privacy (security) may directly or indirectly

contribute to reliable, timely and integrated access to

patient's health data/information (Sahama et al.,

2013). Privacy in healthcare settings refers to

people’s right to control access to their personal

information (Kumar & Wambugu, 2016). Security,

on the other hand, refers to the mechanisms put in

place to safeguard health information and health

information systems from unauthorised access,

modification and denial of service to authorised users

(Kumar & Wambugu, 2016). For providers and

individuals to adopt eHealth, they must trust the

security and privacy of their electronic health

information (Sahama et al., 2013). If patients feel that

the eHealth systems are not secure, they may not use

them to share their health information with healthcare

providers. This has a negative bearing on timely

access to patient information for decision making by

providers.

Non-standardised Health Data Sharing

Mechanisms – Mukasa et al., (2017) recommends

that organisations who intend to share data should

deploy standards as part of their integration efforts.

The purposes of the standards are; to ensure proper

and integratable data formats are captured, those

participating in sharing of health data/information

adhere to a set of rules that govern exchange, only the

right persons have access to a patient’s data, and

security and privacy of patient information are

protected (Adebesin et al., 2013; ITU-T, 2012;

Mukasa et al., 2017). However, our study findings

show that although there are SOPs for sharing of

health information, they are not comprehensive

enough to guide patient data sharing; and procedures

for accessing EMRs are not documented or

documentation is not widely shared. These

shortcomings are a hindrance to timely access or

electronic sharing of patient data. This study suggests

that future development or review of standards for

eHealth should include health facility level users as

part of the stakeholders involved in the development

and/or review of the standards. Furthermore, the

standards for eHealth should be widely provided and

disseminated among all eHealth implementing

agencies and developers.

Organizational Healthcare Environment – in

this study, eHealth governance and leadership, legal

and regulatory frameworks as well as standards have

been reported as key to successful utilization of

eHealth (Hoque et al., 2014; Ishijima et al

., 2015;

Ross et al., 2016). Without an enabling organization

healthcare environment, it may be difficult to

successfully utilize eHealth to realize timely, reliable

and integrated health data (Palabindala et al., 2016).

However, our study findings indicate that there are

insufficient governance structures within Uganda’s

health system to monitor the implementation of

eHealth as well as compliance to standards.

Healthcare is a sensitive domain. If some eHealth

application is going to be used to handle data, proper

governance, as well as procedures and rules, need to

be devised and followed to ensure safe practices of

healthcare services; otherwise, it could lead to serious

consequences. Although the Government of Uganda

has some guidelines and policies in place, the

regulatory and legal framework has not yet been

modernized and or operationalised at health facility

level. This study, therefore, recommends that the

Ministry of Health creates structures at facility level

to oversee the implementation and use of eHealth.

HEALTHINF 2021 - 14th International Conference on Health Informatics

530

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated the impediments to accessing

reliable, timely, and integrated electronic patient data

in healthcare sites in Uganda’s health system.

Findings show the key impediments ranging from

unsuitable mechanisms for electronic health data

collection, storage and access; non-standardised

health data sharing mechanisms; inadequate HIS and

ICT infrastructure; inadequate skills, knowledge and

training; to insufficient security and privacy

measures. Other impediments include weak eHealth

governance and inadequate management support for

eHealth. To mitigate these challenges and attain the

full benefits of eHealth, our future work will generate

requirements that must be met to improve access to

reliable, timely and integrated patient data in the

healthcare sites. The requirements will act as inputs

to the development of contextualised eHealth

standards and an eHealth Enterprise Architecture to

digitally-enable, standardize, implement and use

eHealth in healthcare and service in Uganda.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the Government of the Republic of

Uganda through Makerere University Research and

Innovation Fund for sponsoring the study; and thank

the study participants at the national and sub-national

levels in Uganda’s health system for participating

effectively in the study.

REFERENCES

Aanestad, M., Grisot, M., Hanseth, O., & Vassilakopoulou,

P. (2017). Strategies for Building eHealth

Infrastructures. In M. Aanestad, M. Grisot, O. Hanseth,

& P. Vassilakopoulou (Eds.), Information

Infrastructures within European Health Care: Working

with the Installed Base (pp. 35–51). Springer

International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-

3-319-51020-0_4

Adebesin, F., Kotze, P., Foster, R., & Van Greunen, D.

(2013). A Review of Interoperability Standards in E-

health and Imperatives for their Adoption in Africa.

South African Computer Journal, 50(1), 55–72.

Al-Safadi, L. (2016). The effects of real-time interactive

multimedia teleradiology system. BioMed Research

International, 2016.

Alunyu, A. E., Munene, D., & Nabukenya, J. (2020).

Towards a Digital Health Curriculum for Health

Workforce for the African Region: A Scoping Review.

Journal of Health Informatics in Africa, 7(1), 38–54.

https://doi.org/10.12856/JHIA-2020-v7-i1-265

Anthopoulos, L., Reddick, C. G., Giannakidou, I., &

Mavridis, N. (2016). Why e-government projects fail?

An analysis of the Healthcare. gov website.

Government Information Quarterly, 33(1), 161–173.

Awaisu, A., Mukhalalati, B., & Mohamed Ibrahim, M. I.

(2019). Research designs and methodologies related to

pharmacy practice. Encyclopedia of Pharmacy Practice

and Clinical Pharmacy, 7.

Barello, S., Triberti, S., Graffigna, G., Libreri, C., Serino,

S., Hibbard, J., & Riva, G. (2016). eHealth for patient

engagement: A systematic review. Frontiers in

Psychology, 6, 2013.

Bedeley, R., & Palvia, P. (2014). A study of the issues of E-

health care in developing countries: The case of Ghana.

Castelnuovo, B., Kiragga, A., Afayo, V., Ncube, M.,

Orama, R., Magero, S., Okwi, P., Manabe, Y. C., &

Kambugu, A. (2012). Implementation of provider-

based electronic medical records and improvement of

the quality of data in a large HIV program in Sub-

Saharan Africa. PloS One, 7(12), e51631.

Cohen, L. (2013). Research Methods in Education (7th ed.).

Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203720967

Furstrand, D., & Kayser, L. (2015). Development of the

eHealth Literacy Assessment Toolkit, eHLA. MedInfo,

971.

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., &

Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for

the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary

health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology,

13(1), 1–8.

Gregory, M., & Tembo, S. (2017). Implementation of e-

health in developing countries challenges and

opportunities: A case of Zambia. Science and

Technology, 7(2), 41–53.

Hoque, M. R., Mazmum, M. F. A., & Bao, Y. (2014). e-

Health in Bangladesh: Current status, challenges, and

future direction. The International Technology

Management Review, 4(2), 87–96.

Ishijima, H., Mapunda, M., Mndeme, M., Sukums, F., &

Mlay, V. S. (2015). Challenges and opportunities for

effective adoption of HRH information systems in

developing countries: National rollout of HRHIS and

TIIS in Tanzania. Human Resources for Health, 13(1),

1–14.

ITU-T. (2012). E-health Standards and Interoperability.

Kuipers, S. J., Cramm, J. M., & Nieboer, A. P. (2019). The

importance of patient-centered care and co-creation of

care for satisfaction with care and physical and social

well-being of patients with multi-morbidity in the

primary care setting. BMC Health Services Research,

19(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3818-y

Kumar, M., & Wambugu, S. (2016). A Primer on the

Privacy, Security, and Confidentiality of Electronic

Health Records A Primer on the Privacy, Security, and

of Electronic Health Records. February.

Ministry of Health, Uganda. (2016). Uganda National

eHealth Strategy 2016/2017—2020/2021.

Investigating the Impediments to Accessing Reliable, Timely and Integrated Electronic Patient Data in Healthcare Sites in Uganda

531

Ministry of Health, Uganda. (2017). Uganda Population-

Based HIV Impact Assessment (UPHIA) 2016–2017.

MOH Uganda.

Mukasa, E., Kimaro, H., Kiwanuka, A., & Igira, F. (2017).

Challenges and strategies for standardizing information

systems for integrated TB/HIV services in Tanzania: A

case study of Kinondoni municipality. The Electronic

Journal of Information Systems in Developing

Countries, 79(1), 1–11.

Palabindala, V., Pamarthy, A., & Jonnalagadda, N. R.

(2016). Adoption of electronic health records and

barriers. Journal of Community Hospital Internal

Medicine Perspectives, 6(5), 32643.

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J.

P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful

sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in

mixed method implementation research. Administra-

tion and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health

Services Research, 42(5), 533–544.

Rodziewicz, T. L., & Hipskind, J. E. (2020). Medical Error

Prevention. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499956/

Ross, J., Stevenson, F., Lau, R., & Murray, E. (2016).

Factors that influence the implementation of e-health:

A systematic review of systematic reviews (an update).

Implementation Science, 11(1), 146. https://doi.org/

10.1186/s13012-016-0510-7

Sahama, T., Simpson, L., & Lane, B. (2013). Security and

Privacy in eHealth: Is it possible? 2013 IEEE 15th

International Conference on E-Health Networking,

Applications and Services (Healthcom 2013), 249–253.

Sakovich, N. (2019, April 9). The Importance of Data

Collection in Healthcare and Its Benefits. https://www.

sam-solutions.com:443/blog/the-importance-of-data-

collection-in-healthcare/

Sara, H. (2016, August 11). Top Three Challenges Limiting

Patient Access to Health Data. PatientEngagementHIT.

https://patientengagementhit.com/news/top-3-

challenges-limiting-patient-access-to-health-data

Standing, C., & Cripps. (2015). Critical success factors in

the implementation of electronic health records: A two‐

case comparison. Systems Research and Behavioral

Science, 32(1), 75–85.

Were, M. C., Siika, A., Ayuo, P. O., Atwoli, L., & Esamai,

F. (2015). Building comprehensive and sustainable

health informatics institutions in developing countries:

Moi University experience.

Williams, P., & Coles-Kemp, L. (2014). The changing face

of ehealth security. Electronic Journal of Health

Informatics, 8(2).

HEALTHINF 2021 - 14th International Conference on Health Informatics

532