Evaluating the Meeting Solutions Used for Virtual Classes in Higher

Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Otto Parra

a

and Maria Fernanda Granda

b

Department of Computer Science, University of Cuenca, Av. 12 de Abril s/n, Cuenca, Ecuador

Keywords: Evaluation, Meeting Solutions, User Experience, Usability, Virtual Classroom, Covid-19 Pandemic.

Abstract: When the Ecuadorian government put the country into quarantine as a preventive measure against the Covid-

19 pandemic the country’s schools and colleges had been working normally up to March 2020. On March

13

th

, the University of Cuenca decided to suspend face-to-face classes and changed the system to virtual online

teaching. Although the teachers and students changed the teaching-learning method from face-to-face to

virtual, they were not prepared to continue their education in this new educational system, in which each

student’s family had different mandatory elements (e.g., an Internet connection, computer, meeting solution).

However, they continued the classes through meeting solutions to continue the school year through virtual

classes but without any criteria to select the most suitable meeting tool. This paper evaluates two of the most

commonly used meeting solutions for virtual university classes: Webex and Zoom. We used User Experience

Questionnaire and Microsoft Reaction Cards to evaluate these solutions. The results showed that Zoom was

significantly more attractive than Webex, although there was no significant difference between them in the

classic aspects of usability or user experience.

1 INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic has had a very

strong influence on the development of many areas of

society (UNESCO & IESALC, 2020), including

education (at all levels) (Crawford et al., 2020) and

business (McKibbin & Roshen, 2020). More than 1.5

billion students and young people all over the world

are affected by school and university closures due to

the COVID-19 emergency (Universities, 2020).

According to UNESCO (UNESCO & IESALC,

2020), Ecuador has 5.131.897 learners affected by

COVID-19 (see Figure 1). However, the schools in

the Ecuadorian coastal area, Highlands and Amazonia

run on different schedules.

Just before this pandemic and from September

2019 to July 2020, educational institutions in the

Highlands region had been working in the traditional

way, i.e., activities were carried out normally at

different levels, students and teachers met in

classrooms to learn and teach, respectively. However,

in March 2020 when the first COVID-19 cases were

detected in the country, the situation at all levels of

education in Ecuador changed. The country’s

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3004-1025

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5125-8234

educational authorities made the decision to

quarantine, which meant, among other things, closing

schools, colleges and universities to prevent the virus

from spreading further among the student population.

This decision changed the working environment for

both teachers and students, as they had to stay at

home.

This paper focuses on higher education with the

traditional method (face-to-face), including the

University of Cuenca. In this university, in the

Faculty of Engineering, before the quarantine, 52% of

the teachers used the institution's Moodle-based

virtual platform. This group of teachers had each of

their courses and all the material required to teach the

classes on the virtual platform, which the students

were used to using to participate in forums, chats,

quizzes, review class presentations, read book

extracts, and receive and deliver assignments,

although the classes were given face-to-face. It was

not necessary to use any tool to maintain

communications between teachers and students,

except the traditional tools such as email and

messaging systems (for example, WhatsApp).

190

Parra, O. and Granda, M.

Evaluating the Meeting Solutions Used for Virtual Classes in Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

DOI: 10.5220/0010258201900197

In Proceedings of the 16th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications (VISIGRAPP 2021) - Volume 2: HUCAPP, pages

190-197

ISBN: 978-989-758-488-6

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

In a situation where students are not allowed to go

to educational institutions, the alternative is to move

from traditional to online education. From a

technological point of view, the university authorities

had to consider some very important aspects when

deciding to change the scheme from face-to-face to

virtual: (1) the availability of an internet connection

in all the students and teachers’ homes, (2) the

availability of a computer for education, or (3) a

mobile device with an Internet connection.

Figure 1: Global monitoring of school closures ((UNESCO

& IESALC, 2020)).

In order to teach the students, teachers began to

use the meeting solutions (also called collaboration

platforms that support live-video communications)

available at the University of Cuenca, including

Zoom and Webex. Other tools that have also been

used are Google Meet, and BigBlueButton by

Moodle. Before the pandemic, both teachers and

students were unfamiliar with systems such as Zoom

and Webex to dictate/attend a class, as Skype,

Hangout or WhatsApp were typically used to

communicate with others.

In this context, we were interested in analysing

how well the meeting solutions supported users in

teaching-learning activities. We evaluated usability

and user experience (UX) when the students used

Zoom and/or Webex for their education. According

to ISO 9241-210 (ISO, 2010), UX is defined as

“user’s perceptions and responses that result from the

use and/or anticipated use of a system, product or

service”. ISO 9241-11 (Bevan & Carter, 2016)

defines usability as “the extent to which a system,

product or service can be used by specified users to

achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency

and satisfaction in a specified context of use”.

The major contribution of this work is as follows:

We conducted usability and UX evaluations of two

meeting solutions used in some courses in the

Engineering Faculty in University of Cuenca

(Ecuador) in order to get to know the students’

experience when they use them for classes.

3

https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/edutech/brief/how-

countries-are-using-edtech-to-support-remote-learning-

during-the-covid-19-pandemic

2 BACKGROUND

We use Zoom and Webex because these tools are

available in University of Cuenca for virtual classes.

Webex facilitates teaching, learning, and

collaborative administration anywhere and at any

time. Video conferencing is delivered with a

software-as-a-service (SaaS) model through the

Cisco Webex Cloud. This tool was announced by

Cisco as a free access tool for the Covid-19 pandemic,

Webex supports up to 100 users and includes a

security scheme.

Zoom is a multiplatform meeting solution with a

cloud platform for video and audio conferencing,

collaboration, chats and webinars and can be used

across computers (e.g., desktops, laptops), mobile

devices, and telephones. Its features like chatting,

screen sharing, annotating, whiteboard, polling,

breakout rooms, raising the hand, and managing

participants, lend themselves to creating engaging

virtual hybrid classrooms and collaborating on

projects. Users have the option to record sessions

(Reimers et al., 2020). The free edition permits

meetings of 40 min of duration. The University of

Cuenca has licenses for both Zoom and Webex which

made it easier for us to carry out this research work.

3 RELATED WORK

In this section, we review related works about the

evaluation of UX and usability of meeting solutions

used in the context of virtual education.

In a search of the related literature we found some

papers (Basilaia & Kvavadze, 2020), (Reimers et al.,

2020) and web sites

3

,

4

reporting on the situation of the

education during to COVID-19 and the need to decide

on a meeting solution, although only a few

videoconferencing problems were reported (e.g.,

(Levinsen et al., 2013), (Martin, 2005), (Ørngreen &

Mouritzen, 2013) and (Weitze et al., 2013)). (Khalid

& Hossan, 2017) described a case of summative and

empirical usability evaluation methods of a dedicated

Video Conference System in university classrooms.

However, this study did not analyze the Zoom and

Webex tools and excluded user experience.

(Correia et al., 2020) describe the evaluation of

Zoom, Skype, Microsoft Teams and WhatsApp in the

context of the COVID-19 pandemic. They conducted

an analytic evaluation focused on usability inspection

4

https://elearningindustry.com/virtual-classrooms-role-

during-covid-19-pandemic

Evaluating the Meeting Solutions Used for Virtual Classes in Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic

191

using the Quality in Use Integrated Measurement

(QUIM) model proposed by (Seffah et al., 2006).

These authors do not include Webex in their work.

Additionally, (Singh & Soumya, 2020) describe an

updated comparison between Zoom, Microsoft

Teams, Google Meet, Webex Teams and

GoToMeetings, however, this work do not include

any evaluation about usability or UX. Finally, (Pal &

Vanijja, 2020) describe their work about evaluation

of usability of Microsoft Teams by means of TAM

(Davis, 1989). They do not include an evaluation of

Zoom and Webex.

As the existing literature lacks sufficient

methodological guidance for a usability evaluator to

conduct a study in the classroom of an educational

institution, our objective was to carry out a user-

centered exploratory study to evaluate usability and

UX. To the authors’ best knowledge, no papers have

been published on Zoom and Webex usability studies

or UX for teaching-learning activities in higher-

education.

4 TOOLS TO EVALUATE USER

EXPERIENCE

We used Microsoft Reaction Cards (MRC) (Tullis &

Stetson, 2004) and UEQ (Hinderks et al., 2020) to

evaluate the UX of 79 students of the Faculty of

Engineering of the University of Cuenca who used

Zoom and Webex for their virtual classes during

COVID-19 pandemic.

Product reaction cards were developed by

Microsoft as part of a “desirability toolkit” created to

understand the illusive, intangible aspect of

desirability of UX with a product. 60% of the set of

118 cards contains positive and 40% negative or

neutral words. This ratio is based on Microsoft’s

analysis of higher-than-average positive responses

from participants in completing post-test

questionnaires. Table 1 shows an extract of the cards.

Table 1: An extract of the MRC card set.

Accessible Creative Fast Meanin

g

ful

Advance

d

Confusin

g

Flexible Motivatin

g

Anno

y

in

g

Difficult Fra

g

ile Not Secure

Appealing Date

d

Fresh Novel

Boring Desirable Fun Stable

UX is seen as a holistic concept that includes all

types of emotional, cognitive or physical reactions

concerning the concrete or even only the assumed

usage of a product (Laugwitz et al., 2008). The UEQ

considers aspects of pragmatic and hedonic quality

(Schrepp et al., 2017). Perspicuity, Efficiency and

Dependability represent ergonomic quality aspects,

while Stimulation and Novelty represent hedonic

quality (Laugwitz et al., 2008). The scales of the

questionnaire cover a comprehensive impression of

UX. Both the classical (efficiency, perspicuity,

dependability) and UX aspects (originality,

stimulation) are measured.

The UEQ consists of 26 items grouped into 6

scales (see Table 2).

Table 2: An extract of UEQ.

12345 6 7

annoying ooooo o o enjoyable

creative ooooo o o dull

valuable ooooo o o inferio

r

b

orin

g

ooooo o o excitin

g

fast ooooo o o slow

Each item consists of a pair of terms with opposite

meanings. The items are scaled from -3 to +3, e.g., -3

is the most negative answer, 0 is neutral, and +3 the

most positive (Schrepp et al., 2017). The 26 items in

the questionnaire are arranged into six scales

(Hinderks et al., 2018).

• Attractiveness: Overall impression of the

product. Do users like or dislike it? Is it

attractive, enjoyable or pleasing?

• Perspicuity: Is it easy to get familiar with the

product? Is it easy to learn? Is the product easy to

understand and unambiguous?

• Efficiency: Can users solve their tasks without

unnecessary effort? Is the interaction efficient

and fast? Does the product react to user input

quickly?

• Dependability: Does the user feel in control of

the interaction? Can he or she predict the

system’s behaviour? Does the user feel confident

when working with the product?

• Stimulation: Is it exciting and motivating to use

the product? Is it enjoyable to use?

• Novelty: Is the product innovative and creative?

Does it capture the user’s attention?

5 EVALUATING USER

EXPERIENCE AND USABILITY

5.1 Goal

Analyse the meeting solutions for the purpose of

carrying out a comparative evaluation with respect to

its usability and UX from the point view of the

researchers in the context of the School of Computer

HUCAPP 2021 - 5th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

192

Science in the Faculty of Engineering of the

Universidad of Cuenca (Ecuador).

5.2 Research Questions

In order to study this general goal, we define two

research questions:

• RQ1: When participants have meetings through

the selected tools, is their usability perception

impacted?

• RQ2: Which of the two tools has a higher degree

of user experience?

To answer these research questions, we carried

out one user-centred exploratory study to evaluate

usability and UX.

5.3 Hypotheses

We defined two hypotheses. The null hypotheses

(represented by a 0 in the subscript), which

corresponds to the absence of an impact of the

independent variables on the dependent variables.

The alternative hypotheses involved the existence of

such an impact and are the expected result.

• H

10

Meeting solution does not influence the

usability perception (RQ1).

• H

20

Meeting solution does not influence the UX

(RQ2).

5.4 Variables and Metrics

We consider only one independent variable (a.k.a.

factor (Juristo & Moreno, 2010)) the meeting solution

(Webex and Zoom). As dependent variables (a.k.a.

response variables (Juristo & Moreno, 2010)), we

considered usability and UX, which were expected to

be influenced to some extent by the independent

variable.

5.5 Experimental Context

The study was conducted from 20

th

June to 20

th

July

2020. The teaching-learning activities of the study

programs were given through meeting solutions. The

integration, installation, and positioning of various

components of the meeting solutions depend

significantly on the different factors associated with

the students. The main components required in this

study included a camera, a monitor, speaker,

microphone and Internet connection.

5.5.1 Subjects

The set of experimental subjects was selected by

convenience sampling, i.e., the nearest convenient

persons were selected as subjects. Seventy-nine

Computer Science students (84% males and 16%

females) were invited to participate in the experiment.

Participations was anonymous (aliases were used

instead of names). The subjects did not receive

explicit training on the meeting solutions. A

demographic questionnaire was applied for the

purpose of characterizing subjects according to age,

gender, study level, internet connection quality and

experience with the different meeting solutions used

in the study (see summary in

Table 3).

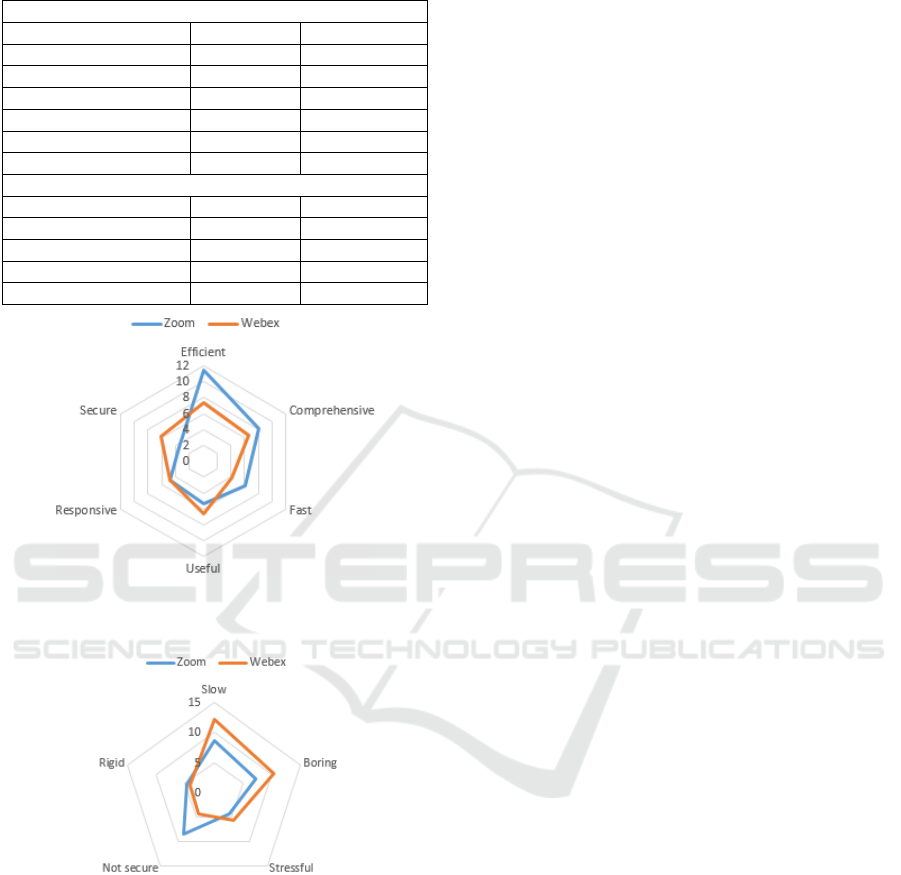

Table 3: Summary of the results of the demographic

questionnaire.

Gender % Age %

Male 84% 18-20 31.6%

Female 16% 21-23 57.9%

>=24 10.5%

Studies

Level

% Quality of Internet

Connection

%

1

st

yea

r

15.8% Ba

d

10.5%

2

nd

y

ea

r

22.8% Not

g

oo

d

45.6%

3

rd

y

ea

r

52.6% Goo

d

35.3%

4

th

y

ea

r

7.0% Ver

y

g

oo

d

8.6%

The results of the demographic questionnaire

show that the subjects were between 18-20 (31.6%),

21-23 (57.9%) and more than 24 years old (10.5%)

comprising 1

st

year (15.8%), 2

nd

year (22.8%), 3

rd

year (52.6%) and 4

th

year (7%) Computer Science

students. Before quarantine, 87% of the students had

not used meeting tools such as Zoom or Webex for

classes or to participate in a course, while the

remaining 13% had some experience in this field.

However, after March 13

th

, all the students began to

familiarize themselves with both tools of the Moodle-

based virtual platform. Another important detail was

related to the quality of the students’ home Internet

connection. According to the questionnaire, only

8.6% had a very good Internet connection. 35.3% had

a good connection, 45.6% had a not good connection

and 10.5% a bad. This factor could have had an

impact on UX when using Zoom or Webex.

5.5.2 Experimental Design

A within-subject design was selected for the

experiment. This design equates the conditions by

using the same participants in each condition, which

removes individual differences. The order in which

the subjects tested the different meeting solutions was

randomized. The participants were divided into four

groups from the four years of the Computer Science

Evaluating the Meeting Solutions Used for Virtual Classes in Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic

193

course and all used Zoom and Webex to perform the

tasks specified in the teaching-learning process.

5.5.3 Experimental Procedure

The empirical study began with a short presentation

in which general information and instructions were

given, after which the demographic questionnaire was

applied. The tasks involved in the evaluation were:

attending classes, working in groups and sharing

screens. The tasks took approximately twenty

minutes, using Webex and Zoom on different days.

After completing the tasks, they used MRC and UEQ

to evaluate UX and usability. In MRC, they selected

five positive and five negative adjectives for both

meeting solutions and in UEQ they evaluated UX.

6 RESULTS

6.1 UEQ Results

In the next step, we gave to the subjects the UEQ to

evaluate their UX of the meeting solutions to stay in

class. From the answers of the questionnaire and UEQ

tool (available in the UEQ)

5

we obtained the results

of classical usability aspects (efficiency, perspicuity,

dependability) and UX (originality, stimulation).

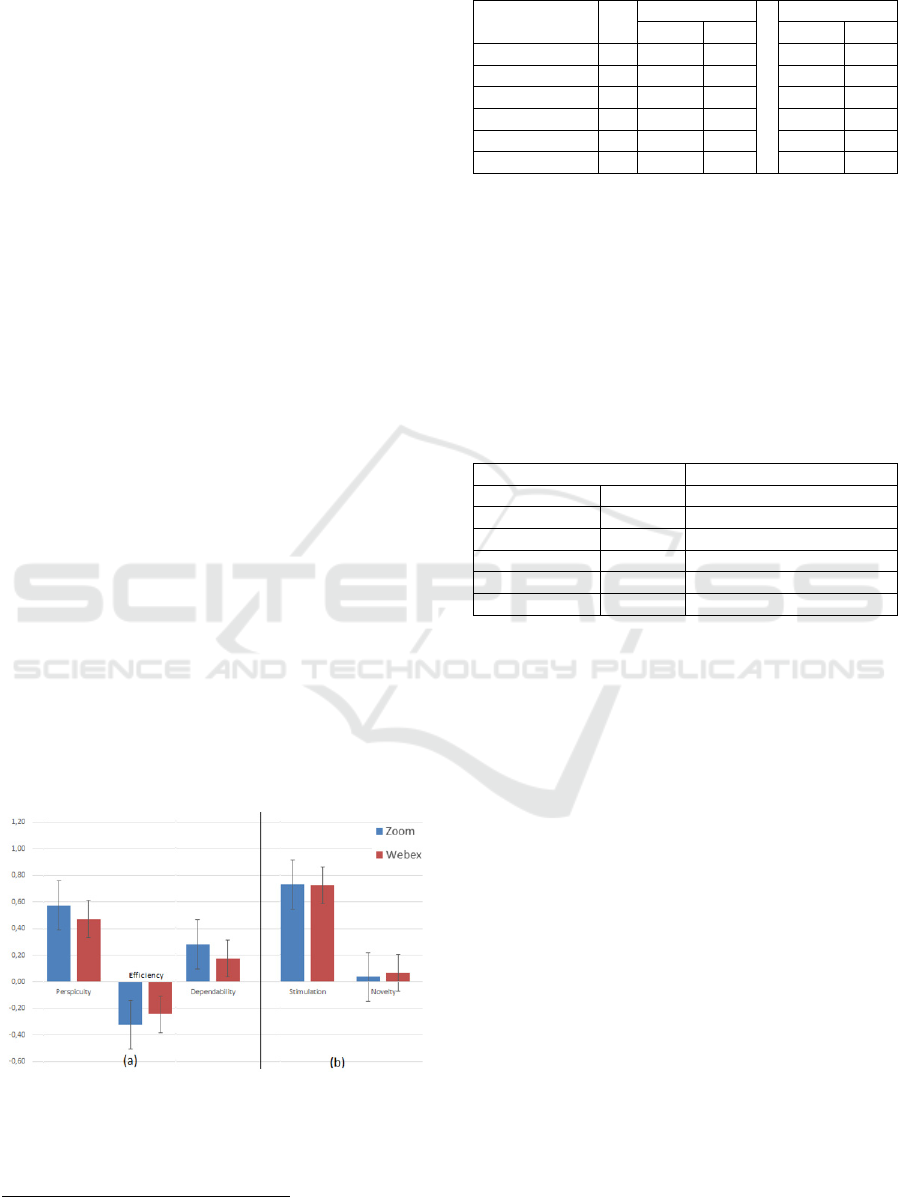

The results obtained from the UEQ related with

classical usability aspects (perspicuity, efficiency,

dependability) are shown in the bar diagram (Figure

2 (a)), where the bars on the left are those of Zoom

and those on the right from Webex. Efficiency was

given a negative value for both tools (Zoom: -0.32

and Webex: -0.24). We also used a bar diagram to

describe the UEQ UX results (stimulation and

novelty). (Figure 2 (b)).

Figure 2: Results of (a) classical usability aspects, (b) user

experience.

5

https://www.ueq-online.org/

Table 4: Comparison of scale means.

Scale N

Zoom Webex

Mean Std. Mean Std.

Attractiveness 79 0.86 0.59 0.41 0.79

Perspicuit

y

79 0.57 0.77 0.47 0.70

Efficienc

y

79 -0.32 0.58 -0.24 0.60

Dependabilit

y

79 0.28 0.56 0.17 0.54

Stimulation 79 0.73 1.08 0.72 1.08

Novelt

y

79 0.04 0.63 0.07 0.66

Table 4 includes the Zoom and Webex results

after applying the statistics to the UEQ values. Table

5 shows a simple T-Test to determine whether the

scale means of the two meeting solutions differed

significantly (alpha level 0.05). It can be seen note

that there is not significant difference in the aspects

for classical usability or in UX aspects between both

meeting solutions. Regarding the attractiveness, it can

be seen there is a significant difference between

Zoom and Webex.

Table 5: T-test results obtained with UEQ tool.

Al

p

ha level: 0.05

Attractiveness 0.0001 Si

g

nificant difference

Perspicuit

y

0.3900 No significant difference

Efficienc

y

0.3978 No significant difference

De

p

endabilit

y

0.2190 No si

g

nificant difference

Stimulation 0.9707 No si

g

nificant difference

Novelt

y

0.7821 No si

g

nificant difference

6.2 MRC Results

Table 6 shows the results obtained from MRC on UX

with two groups of values classified as positive and

negative adjectives for each meeting solution. The

results obtained in the Zoom user experience

evaluation by MRC are classified in two groups: (i)

the five highest scored positive adjectives (Figure 3):

efficient (11.4%), comprehensive (8.1%), fast

(6.1%), useful (5.3%) and responsive (4.8%). (ii) The

five highest scored negative adjectives (Figure 4):

slow (8.6%), not secure (8.4%), boring (7.3%), rigid

(4.8%), and stressful (4.3%).

Figure 3 gives the results obtained from the

Webex evaluation of UX by means of MRC. The five

highest scored positive adjectives are: efficient

(7.34%), comprehensive (6.58), useful (6.58), secure

(6.08) and responsive (4.81%), while Figure 4 gives

the five highest scored negative adjectives: slow

(12.2%), boring (10.4%), stressful (5.6%), not secure

(4.3%), rigid (4.1%), unattractive (4.1%) and

inconsistent (4.1%).

HUCAPP 2021 - 5th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

194

Table 6: The five highest scored positive and negative

adjectives for MRC.

The five highest scored positive adjectives

Adjective Zoom (%) Webex (%)

Efficient 11.4 7.3

Com

p

rehensive 8.1 6.6

Fast 6.1 4.2

Useful 5.3 6.6

Responsive 4.8 4.8

Secure 3.5 6.1

The five highest scored negative adjectives

Slow 8.6 12.2

Borin

g

7.3 10.4

Stressful 4.3 5.6

Not secure 8.4 4.3

Rigi

d

4.8 4.1

Figure 3: The five highest scored positive adjectives for

Zoom and Webex obtained by applying MRC.

Figure 4: The five highest scored negative adjectives for

Zoom and Webex obtained by applying MRC.

7 ANALYSIS OF RESULTS

7.1 UEQ

We considered the results obtained with UEQ to

answer the research questions:

Usability is related with three factors: efficiency,

dependability, and perspicuity. From the results

obtained in the evaluation, described in the Table 5

and shown in Figure 2, we can see that there is no

significant difference between using Zoom and

Webex for classes. However, the efficiency values

obtained in the evaluation are negative: -0.24 for

Webex and -0.36 for Zoom. This implies that the

participants had to make an effort to follow their

classes using both meeting solutions, although less

effort was required with Webex than Zoom. The other

two factors (dependability - Does the user feel

confident when working with the product? and

perspicuity - Is it easy to get familiar with the

product?) obtained very similar mean and SD values,

which means that students found it easy to become

familiar with both meeting solutions and felt

confident in using them.

UX is related with two factors: originality and

stimulation. According to the results obtained in the

evaluation, there is no significant difference in the

UX between Zoom and Webex for classes. The

results obtained for the originality (Is it exciting and

motivating to use the product?) and stimulation or

novelty (Is the product innovative and creative?) have

similar values, showing that the students regarded

these tools as a novelty. They also saw these solutions

as innovative and considered that they help them

resolve their current situation of not being able to

attend classes. In both cases, the null hypotheses

proposed in our work were accepted.

7.2 MRC

From the analysis of MRC results to determine the

users’ opinion, the following can be said: (i) using

positive adjectives to compare both meeting

solutions, we can conclude than Zoom is considered

more efficient than Webex (Figure 3). The

participants considered Zoom more useful,

responsive and faster than Webex.

Considering the negative adjectives (Figure 4), we

can conclude that the participants considered Zoom to

be less secure than Webex, although Zoom was

considered less stressful than Webex. Regarding the

negative adjective “Slow”, Webex was slower than

Zoom. This result could have been influenced by the

quality of the participants’ Internet connection. In the

answers to the demographic questionnaire 56.1% said

that their Internet connection was “bad” or “not

good”.

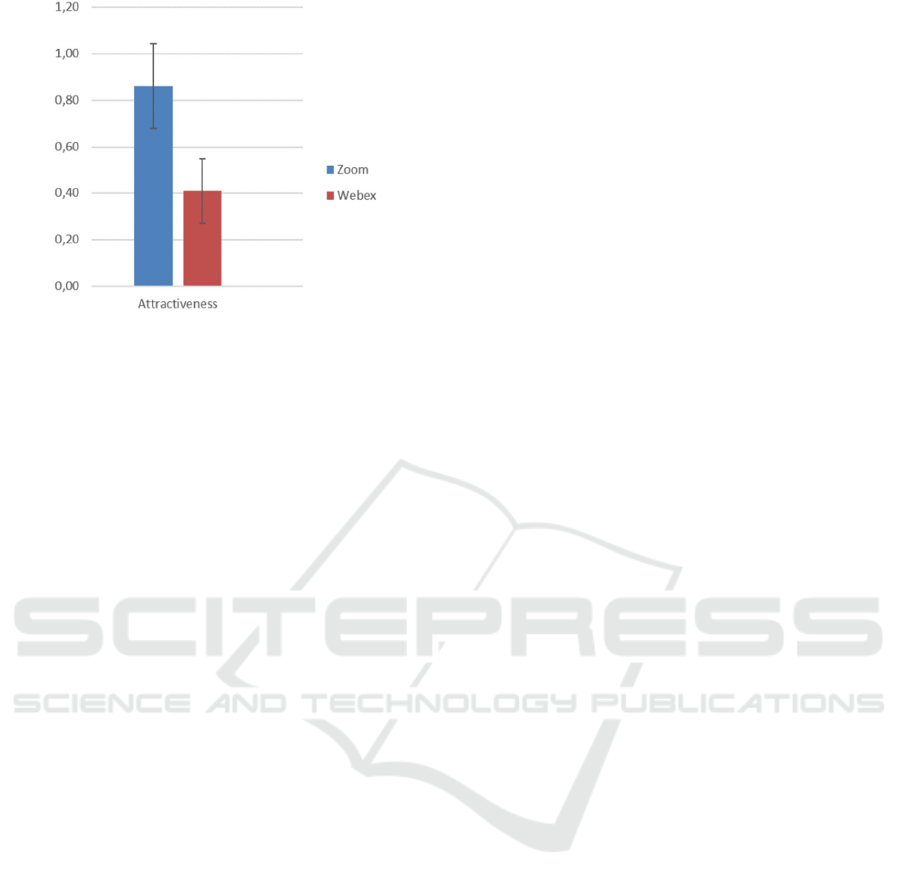

The “attractiveness” factor measures the overall

impression of the product and answers the question

“Do users like or dislike it?” The participants had a

better impression of Zoom that Webex and they like

preferred it for virtual classes (Figure 5, blue bar:

Zoom, red bar: Webex).

Evaluating the Meeting Solutions Used for Virtual Classes in Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic

195

Figure 5: Results of attractiveness obtained from UEQ tool.

8 VALIDITY THREATS

In this work, we considered some validity threats

which could have influenced the UX and usability

results.

The threats to the validity of the conclusions are

concerned with issues that affect the ability to draw

the correct conclusion about the relations between the

treatment and the outcome of an experiment.

a) Reliability of Measures: The validity of an

experiment is highly dependent on the reliability

of the measures. In general, objective measures

are more reliable than subjective measures. In

order to reduce this threat, we used the tested UEQ

and MRC for measuring UX and usability.

However, in this experiment, the precision of

efficiency may have been affected by the

participants’ different qualities of their Internet

connection and devices.

b) Reliability of the Application of Treatments to

Subjects: The application of treatments to

subjects should be as standard as possible for

different subjects and occasions. This factor could

have been affected since the evaluations were

carried out on different occasions. To ensure

maximum similarity, a standard procedure was

designed to be similarly applied by the

experimenter on each occasion. In addition, as the

subjects’ perception could have been affected by

the order and time of the evaluation, the tasks

were assigned randomly with the purpose of

diminishing this threat.

Threats to internal validity concern issues that

may indicate a causal relationship even though there

is none.

a) Instrumentation refers to the effect caused by the

instruments used in the experiment. If these are

badly designed, the experiment is affected

negatively. To minimize this threat, all the

instrumentation and tasks were pre-validated by

two persons. Furthermore, UEQ and MRC forms

were provided in web form, the data collection

and the statistical analysis was double checked.

We also used the UEQ tool available on the UEQ

website to get the results of the classical aspects

of usability and UX.

Threats to external validity concern the ability to

generalize experiment results outside the experiment

setting.

a) Interaction of Selection and Treatment: This is

the effect of not having a representative

population from which to generalize the results of

the experiment. This factor could have affected

the experiment results since the subjects had

similar levels of experience in using the different

meeting solutions. Further experiments with a

more heterogeneous sample of subjects will be

necessary to confirm the results obtained.

b) Interaction of Setting and Treatment: This is

the effect of not having representative material. In

the experiment we carefully selected a

representative task. However, more empirical

studies with other tasks could also be necessary.

Regarding the selection of the meeting solutions,

we consider that Zoom and Webex are

representative solutions we plan to replicate this

experiment with other meeting solutions for

teaching-learning activities.

9 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

The aim of our research work was to get an overall

picture of the usability and UX of two meeting

solutions used in a virtual teaching-learning

environment during COVID-19 pandemic.

Applying the UEQ and Microsoft Reaction Cards

we obtained results that indicated that Zoom was

considered significantly more attractive than Webex.

However, there was no significant difference in the

classic aspects of usability and UX. As our study only

covered the Faculty of Engineering, we will extend

our research to all the faculties at the University of

Cuenca to measure the impact of COVID-19 on the

educational process when the teaching method is

changed from face-to-face to virtual. Different

stakeholders have different usability goals because

they are involved in different activities (teaching

sessions, laboratory practices, technical support,

interview with students, etc.) and this can affect the

evaluation of usability.

HUCAPP 2021 - 5th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction Theory and Applications

196

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work has been supported by Dirección de

Investigación de la Universidad de Cuenca (DIUC) –

Ecuador.

REFERENCES

Basilaia, G., & Kvavadze, D. (2020). Transition to Online

Education in Schools during a SARS-CoV-2

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic in Georgia.

Pedagogical Research, 5(4).

Bevan, N., & Carter, J. (2016). Human-Computer

Interaction. Theory, Design, Development and Practice.

In International Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction (Pp. 268-278). Springer, Cham.,

9731(July), 268–278.

Correia, A. P., Liu, C., & Xu, F. (2020). Evaluating

videoconferencing systems for the quality of the

educational experience. Distance Education, 41(4),

429–452.

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, K., &

Malkawi, B. (2020). COVID-19: 20 Countries’ Higher

Education Intra-Period Digital Pedagogy Responses

Crawford,. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching,

3(1), 1–20.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived Ease of Use, and User

Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS

Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340.

Hinderks, A., Domínguez-Mayo, F., Meiners, A., &

Thomaschewski, J. (2020). Applying Importance-

Performance Analysis (IPA) to Interpret the Results of

the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ). Journal of

Web Engineering, 19(2), 243–266.

Hinderks, A., Schrepp, M., & Thomaschewski, J. (2018).

User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ). ueq-online.org

ISO. (2010). Ergonomics of human-system interaction —

Part 210: Human-centred design for interactive

systems. ISO 9241-210:2019(En).

https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9241:-210:ed-

2:v1:en

Juristo, N., & Moreno, A. (2010). Basics of Software

Engineering Experimentation (1st. Ed.). Springer

Publisher Company.

Khalid, M. S., & Hossan, M. I. (2017). Usability evaluation

of a video conferencing system in a university’s

classroom. 19th International Conference on Computer

and Information Technology, ICCIT 2016, 184–190.

Laugwitz, B., Held, T., & Schrepp, M. (2008). Construction

and Evaluation of a User Experience Questionnaire. In

A. Holzinger (Ed.), HCI and Usability for Education

and Work. USAB 2008. Lecture Notes in Computer

Science. Symposium of the Austrian HCI and Usability

Engineering Group (Vol. 5298, pp. 63–76). Springer,

Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-

89350-9_6

Levinsen, K. T., Orngreen, R., & Buhl, M. (2013).

Telepresence as educational practice in the third

teaching-room-a study in advanced music education.

Proceedings of the European Conference on E-

Learning, ECEL, September 2017, 250–257.

Martin, M. (2005). Seeing is believing: The role of

videoconferencing in distance learning. British Journal

of Educational Technology, 36(3), 397–405.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00471.x

McKibbin, W. J., & Roshen, F. (2020). The Global

Macroeconomic Impacts of COVID-19: Seven

Scenarios. SSRN Electronic Journal,

March.

https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3547729

Ørngreen, R., & Mouritzen, P. (2013). Video Conferencing

in a Collaborative and Problem Based Setting. In M. A.

Mélanie Ciussi (Ed.), Proceedings of the 12th

European Conference on e-Learning (pp. 360–368).

Academic Conferences and Publishing International.

Pal, D., & Vanijja, V. (2020). Perceived usability evaluation

of Microsoft Teams as an online learning platform during

COVID-19 using system usability scale and technology

acceptance model in India. Children and Youth Services

Review, 119(October), 105535.

Reimers, F., Schleicher, A., Saavedra, J., & Tuominen, S.

(2020). Supporting the continuation of teaching and

learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Annotated

resources for online learning. OECD 2020, 1–38.

Schrepp, M., Hinderks, A., & Thomaschewski, J. (2017).

Construction of a Benchmark for the User Experience

Questionnaire (UEQ). International Journal of

Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence, 4(4),

40. https://doi.org/10.9781/ijimai.2017.445

Seffah, A., Donyaee, M., Kline, R. B., & Padda, H. K.

(2006). Usability measurement and metrics: A

consolidated model. Software Quality Journal, 14(2),

159–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11219-006-7600-8

Singh, R., & Soumya, A. (2020). Updated comparative

analysis on video conferencing platforms- Zoom,

Google Meet, Microsoft Teams, WebEx Teams and

GoToMeetings. EasyChair: The World for Scientists,

1–9. https://easychair.org/publications/preprint/Fq7T

Tullis, T. S., & Stetson, J. N. (2004). A Comparison of

Questionnaires for Assessing Website Usability

ABSTRACT : Introduction. Usability Professional

Association Conference, 1–12.

http://home.comcast.net/~tomtullis/publications/UPA2

004TullisStetson.pdf

UNESCO & IESALC. (2020). COVID-19 and higher

education: Today and tomorrow. Impact analysis,

policy responses and recommendations. 1–46.

https://bit.ly/34TOSvu

Universities, I. A. of. (2020). Covid-19: Higher Education

challenges and responses. https://www.iau-

aiu.net/Covid-19-Higher-Education-challenges-and-

responses

Weitze, C. L., Ørngreen, R., & Levinsen, K. (2013). The

global classroom video conferencing model and first

evaluations. Proceedings of the European Conference

on E-Learning, ECEL, September, 503–510.

Evaluating the Meeting Solutions Used for Virtual Classes in Higher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic

197