Responding to COVID-19:

Potential Hospital-at-Home Solutions to Re-configure the Healthcare

Service Ecosystem

Nabil Georges Badr

1a

, Luca Carrubbo

2b

and Marguerita Ruberto

2c

1

Higher Institute for Public Health, Saint Joseph University, Beirut, Lebanon

2

Department of Business Sciences, Management and Innovation Systems, Salerno University,

Via Giovanni Paolo II, 132, Fisciano (SA), Italy

Keywords: Hospitalization at Home, Systems Thinking, Viable System, Complex Ecosystems, Healthcare Service

Ecosystems.

Abstract: An effective Healthcare Service Ecosystem must emphasize the notion of well-being co-creation which entails

a dynamic interplay of actors, in face of the challenges, with their ability to use the available resource pools,

at the different system levels. An appropriate response, largely avoiding any crisis, depends on a society's

resilience and the related response of actors in the reconfiguration of resources. Originally considered luxury

and for the fortunate few who could afford the learning curve, Hospitalization-at-Home (HaH) recently

approached a new normal with a positive impact to health outcomes. Nowadays, hospitals have had to

reconfigure their health services to reduce the workload of caregivers during the COVID-19 outbreak. Our

use case can be a lesson for the adaptation of technology for patient empowerment allowing patients to interact

with their care ecosystem while at their home.

1 INTRODUCTION

An effective Healthcare Service Ecosystem (H-SES)

(Frow et al., 2014) must emphasize the notion of well-

being co-creation which entails a dynamic interplay

of actors, in face of the challenges, with their ability

to use the available resource pools, at the different

system levels (Häring et al., 2017).

In pandemics, an essential healthcare disaster per

sort, the social as well as the service-related fabric of

society, supply chains (Bonadio et al., 2020) and even

the complete industry are changed. An appropriate

response, largely avoiding any crisis, depends on a

society's resilience and the related response of actors

in the reconfiguration of resources (Finsterwalder &

Kuppelwieser, 2020). Healthcare systems are no

exception (P2PH, IHI.ORG). “The COVID-19 era is

bringing new attention and urgency to people’s social

needs, the impact of unmet needs on health, and the

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7110-3718

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3530-1298

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2247-5894

importance of partnership among health systems and

community organizations” (P2PH, IHI.ORG).

New behaviours have to be learned for society to

maintain the well-being of its constituents and new

processes put in place and for the survival of the

multiple, and the sustainability of related ecosystems

in support of society. Healthcare Service Ecosystems

have to support new concepts and services;

technology deployment that facilitates telemedicine,

care at home and consultation at a distance must be

accelerated to expand the public’s access to essential

health services during the COVID-19 Pandemic

(CDC.ORG).

1.1 Motivation

Healthcare systems have buckled under the health

emergency in the pandemic, due to insufficient

hospital availability of beds, long waiting times, lack

of adoption of intervention plans for emergencies,

lack of medical and health personnel, of the total

344

Badr, N., Carrubbo, L. and Ruberto, M.

Responding to COVID-19: Potential Hospital-at-Home Solutions to Re-configure the Healthcare Service Ecosystem.

DOI: 10.5220/0010228103440351

In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2021) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 344-351

ISBN: 978-989-758-490-9

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

absence of coordination between the different ones’

actors and, above all, the lack of an adequate

assistance territorial network (Grimm, 2020).

Furthermore, the delay in the digitization process and

the presence of IT systems fragmented made it

difficult to exchange information with serious

repercussions on timeliness of the implementation of

all control measures.

For practitioners, the sudden unbalance between

health care needs and available resources has confront-

ed health professionals’ ethical choices with the need

to make decisions in time very short, paying a high toll

also in terms of human lives (Baily et al., 2007).

For patients, the pandemic has confined the

population to their homes. Those ridden with chronic

illnesses must have access to supervised and

continued care. In all, medical healthcare providers

are under an enormous amount of workload pressure,

faced with high risks and shortages of available

services, along with increased total health

expenditure (Moazzami et al., 2020).

This situation sheds the spotlight on the

importance of a reorganization of health services and

can be seen as the perfect storm motivating healthcare

ecosystems to include care at home technologies in

their mainstream. Aside from building responsive

information systems for a timely collection of

information for timely and relevant decision-making,

a paradigm shift in care models must rely on the

empowerment of territorial health care aimed at an

effective taking charge of patients both in terms of

appropriateness of care and clinical governance

(Breslow et al., 1992).

Originally considered luxury and for the fortunate

few who could afford the associated learning curve,

Hospitalization-at-Home (HaH) (Leff, 2001)

approached a new normal with a positive impact to

health outcomes. A recent study found that

substitutive home hospitalization not only reduce cost

by 38%, by improved patient experience. At the

comfort of their home, patients spent a smaller

proportion of the day sedentary and were readmitted

less frequently within 30 days (7% vs. 23%), mainly

due to the lack of potential infections risks, otherwise

extant in traditional hospital settings (Levine et al.,

2020). Clinicians are leading service reconfiguration

to cope with COVID-19. They are learning new

skills, adapting and exploiting new means of

consultations, like the use of video clinics (Thornton,

2020) for example. In other cases, hospitals have had

to reconfigure their health services to reduce the

workload of caregivers during the COVID-19

outbreak, such in the case of the deployment of easy

to use software / devices that allow patients to interact

with their care ecosystem while at their home. In

general, direct-to-consumer telemedicine products,

for instance, can enable patients to connect with their

healthcare provider at a distance. This indicates that

Healthcare ecosystems have had to learn to

reconfigure their resources.

Therefore, “HaH can be viewed as a practical

expression of H-SES adaptive features, re-

configuration ability and modular design on the

grounds of the System Thinking perspective”. The

adaptation of processes and technology can empower

patients to interact with their care ecosystem while at

their home. What HaH Solutions can provide

insight to the potential of re-configuration of

Healthcare Service Ecosystems?

To illustrate our thinking, we formed this

manuscript under the lens of systems thinking applied

to Service Ecosystems (Section 2.1) of healthcare

with the example of HaH as evidence (Section 2.2)

and posturing the value of technology as the central

component (Section 2.3) with a use case that treats the

topic (Section 3) and draws some challenging issues

(Section 4).

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Healthcare Service Ecosystems

Starting from the recent advance in service research

on H-SES, a number of reflections have been

synthetized in terms of the actors’ engagement and

participation (Frow et al., 2019), including formal and

informal caregiver interactions (Badr et al., 2018).

Special attention has been given to the design and re-

configuration, adaptive processes, and the ability to

face the emergence in the systems (Capunzo et al.,

2013; Carrubbo et al., 2013; 2016; Ciasullo et al.,

2017).

Essentially, Healthcare Service Ecosystems can

be viewed as complex service ecosystems (Ciasullo

et al., 2017), due to the distinctive features and the

ability the re-configure fundamental resources in

reaction or anticipation of external events, where

decision-makers have to manage complex

interactions between several different actors or

entities (e.g., patients, health providers and suppliers,

etc.). Through the lens of system thinking, the

capability of reconfiguration of multiple resources to

deliver value in a different modality requires an

adaptive, cognitive alignment for maintaining the

system’s viability; i.e. the ability of Actors in the

system to 'continue' their actions and survive the

impending events. systems that aim to survive in their

Responding to COVID-19: Potential Hospital-at-Home Solutions to Re-configure the Healthcare Service Ecosystem

345

living context by establishing harmonic relationships

with other entities that own the resources necessary

for their functioning and survival (Barile et al., 2012a;

2012b; 2016). All parts of the system are

interconnected and interact with each other, providing

continuous feedback that serves as a learning cycle

for capability reconfiguration in response to a certain

event. Inherent in these dynamic capabilities of

reconfiguration is a level of complexity (variety,

variability, indeterminacy).

2.2 Hospitalization-at-Home

HaH is one one approach for a H-SES to solve

problems and adapt to evolving contingencies,

transforming the model of care. HaH is based on the

implementation of alternative forms for health

assistance such as healthcare residences, home care,

intermediate care, community mail, and weekend

shipments (Caputo, 2018). From a more general

perspective, the main value proposition of HaH is the

reduction in the number of hospitalizations and the

related reduction of hospital care costs and clinical

risks (Hwang et al., 2008). The changes in care settings

(Al-Balushi et al, 2014), and on the cost reduction for

managing hospital health processes (Bodenheimer et

al, 2020), are also indicative of this transformation. To

achieve this aim, HaH proposes a redefinition (re-

configuration) of the hospital as an advanced place of

care, and it underlines the need for specific

organizational paths directly so as to identify the

procedures for collecting timely and up-to-date data

about health services demand and the resources used

during the health processes. This implies new modes to

intend value, influenced by contextualization (value-

in-context), personal patient’s use (value-in-use) and

their own direct experiences (value-in-experience)

(Polese et al, 2018) as they have been exploited by

service scholars worldwide in last dacades.

Firstly, HaH can be considered as an alternative

approach to consolidated health treatments, because

it aims at organizing in the patient’s home a “care

setting” equivalent to the hospital one, helpful for

chronic illnesses, able to increase patient and

caregiver satisfaction so as to improve patients’

quality of life and to reduce the health processes

costs. Expanding the value to different contexts of the

ecosystem, HaH clinical activities are managed both

at a local (hospitals and districts) and regional level;

the activities of diagnosis, treatment, monitoring, and

rehabilitation are provided within several constraints

in care quality (i.e., waiting time), efficiency (i.e.,

resource utilization), and costs (i.e., fixed annual

savings or budget reduction) (Ignone et al, 2013).

Secondly, thanks to this alternative approach to

healthcare processes, HaH introduces new forms of

responsibility and engagement in the health domain,

offering to patients and their families the opportunity

to acquire the knowledge and competencies useful to

proactively collaborate with health professionals

(Rodríguez et al, 2013).

Thirdly, HaH can positively impact on patients’

quality of life and it can increase efficiency in the use

of the available resource for satisfying the collective

need for health. Considering the multiple potential

contributions provided by HaH for increasing the

efficiency and sustainability of H-SES, several

approaches have been proposed for evaluating its

dynamics, focusing attention on the decrease in

hospitalizations (Cohen et al, 1996), therefore

bolstering the overall value-in-experience of this

extended form of care.

Therefore, through hospitalization at home, H-

SES can re-configure itself and re-organize itself for

increasing the capability of the multiple needs of

patients (Polese, Carrubbo, 2016). In a nutshell,

according to Wilson (2018), the most relevant

advantages provided by HaH practice can be

summarized by provisioning components of

interdisciplinary team-based community care as part

of integrated care with other sectors, bridging

restorative approaches to care with the support for

caregivers as part of home care (Polese et al, 2018).

2.3 The Emergence of Telemedicine

and Assistive Devices

At the centre of the reconfiguration capability of the

H-SES, health technology should be patient centric,

and focus on the interaction between the patient and

the multiple actors and services in the healthcare

ecosystem.

Effective solutions have been developed to manage

the interaction among the care team (Badr et al, 2018),

provide assistive functions (assistive technologies) and

improve the patient’s quality of life (Sofaer &

Firminger, 2005; Moliner, 2009; Sweeney et al, 2015).

Through the deployment of point of use systems and

software based on principles of communication, data

management, patient engagement has become key to

the expansion of the H-SES (Britt et al, 2005; Gruman

et al, 2010; Polese & Carrubbo, 2016). For instance,

telehealth adoption is expanding the accessibility to

healthcare service beyond the traditional setting, with

services such as virtual consultation, allowing access

to cost-effective care. Soon, telepresence physicians

will use robots to help them examine and treat patients

in rural or remote locations (ASME.ORG).

HEALTHINF 2021 - 14th International Conference on Health Informatics

346

The increase of consumerism in remote healthcare

devices is democratizing current healthcare systems.

Consumer-driven care delivery models such as

telehealth, e-pharmacy, retail care, price

transparency, push care closer to the point of the

person, among others. Examples are wearable devices

such as heart monitors that can detect atrial

fibrillation, blood pressure monitors, self-adhesive

biosensor patches that track your temperature, heart

rate, will help consumers proactively get health

support. Drug delivery devices such as insulin pens,

biologic auto injectors, inhalers, and smart packaging

for pills will be commonplace to enhance both

clinical and business operations in healthcare

(https://flex.com/industries/healthcare)

As an emerging technology, it is unrealistic to

expect that solutions as such to be based on

standardizations, given the high degree of

heterogeneity of integrated care practices in place,

and the impossibility of forecasting future demands

for care. However, it is an indication that the H-SES

is attempting to reconfigure itself through the use

technology among others.

3 HAH EXPERIMENTAL USE

CASE

Here, we introduce an interesting use case

exemplifying reconfigurable Healthcare Ecosystems.

The setting of our example is in South of Italy, in

Salerno City (Campania Region).

3.1 The ‘ADD-Protection’ Co-financed

R&D Project

The Project was named ‘ADD-Protection’ to mean

the increase of care provision to defend the health of

the community, additional to the traditional protocol

already existing. This attempt was before COVID-19

situation, but still represent a best practice to

efficiently respond to uncertain and unpredictable

conditions that can occur over time. Results explain

how the innovative solution proposed can effectively

support a new organization and design of healthcare

service (seen as a whole) when needed, and today

give us (scholars, practitioners, medical employees,

managers and politicians) a very relevant suggestion

to perform a continuative care in the unusual and we

are living now.

The Project was about 1 year long and gave lots

of insightful information about the problems and the

opportunities to improve the performance level and

quality by offering modular technology solutions

with a high potential to enable evolutions in the global

Healthcare Service Ecosystem as a whole.

The experiments involve 50 persons (40-85 years

old) affected by 3 special pathologies: diabetes in

adults, heart difficulties, breath chronical problems.

3.2 The ‘ADD-Protection’ Research

Activities

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, The Hospital of

Salerno, named San Giovanni di Dio Ruggi

d’Aragona in San Leonard – launched an experiment

in collaboration with SIMAS Intedept., a research

Centre of Salerno University and a local firm Magaldi

Life Ltd. The attempt was to develop a new protocol

to evaluate specific cases of chronic disease of long-

term patient, in the aim to provide care to their homes.

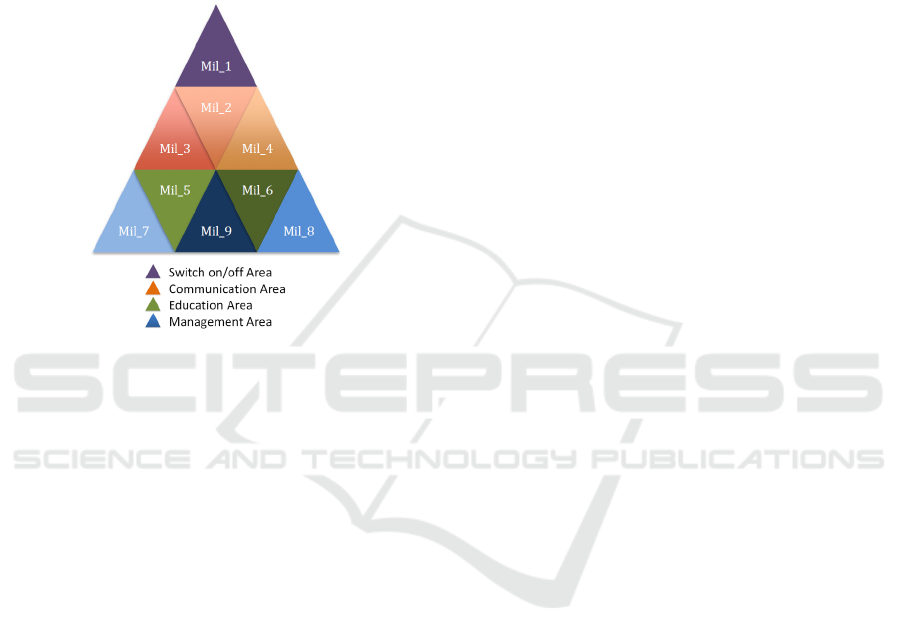

The project included multiple milestones (Figure

1) incorporating the expansion of the definition of a

multimode medical service protocol and communica-

tion plan, the development and implementation of an

information system for remote medical examination

and the supporting infrastructure. The technology

implemented allowed for the monitoring of vital signs

and the detection of early warning. The project also

accounted for cost reduction measures, changes in the

related processes, the diffusion of training to the

actors in the service, including informal caregivers.

The following project plan was laid out to manage

and monitor the activities in the following milestones:

• MIL_1 - Development of an election procedure

for the definition of the perimeter of

"appropriateness of protected discharge" in a

logic that may include, alongside the dual option:

HOSPITAL - HOME; a multipolar option:

HOSPITAL - HOME and / or local RSA and / or

HOSPICE.

• MIL_2 - Development of a systemic and

multichannel communication plan through which

the hospital structure informs its context around

the value of the Protected Discharge model. The

aim was to calibrate the awareness to improve the

positive reception of the service and also

removing all the elements of disinformation that

it could reduce the effectiveness of the project to

the extreme of its failure.

• MIL_3 - Development of a REMOTE

MEDICAL EXAMINATION system aimed at

activating a direct communication channel

between patients and operators - in particular

hospital doctors - which allows a level of

continuity of care that is truly accessible by the

Responding to COVID-19: Potential Hospital-at-Home Solutions to Re-configure the Healthcare Service Ecosystem

347

patient, especially assessment of clinical

conditions, functional and cognitive status.

• MIL_4 - Development of a dedicated IT platform

for sharing information (knowledge management)

between the parties involved in the service, with

particular reference to: progress of the treatment

plan, list of open problems, status of achievement

of objectives, and improve level of satisfaction of

the patient and family (process management

information).

Figure 1: Milestone Project Areas - From

(www.magaldilife.it).

• MIL_5 - Development of new staff training

(doctors and nurses) and any other actor involved

in the service.

• MIL_6 - Development of a new approach to

communication, involvement and active

participation of discharged subjects and their

families (informal care giver).

• MIL_7 - Development of an alert procedure that

allows you to collect weak signals and weigh the

risk factors that can lead to an early return to

hospital, not limited to health factors related to

the patient but also to those of family

sustainability.

• MIL_8 - Development of a cost logic that goes

towards the concept of "care budget", for the

elaboration of an individual Care Plan ad hoc for

the de-hospitalized patient.

• MIL_9 - Development of a renewed coordination

of activities in accordance with the principles of

Project Management, by virtue of the lower level

of standardization of each intervention.

3.3 The Technologies Used

This HaH project was enabled by technologies such

as electronic medical records, real-time diagnosis

with go-pro cam, Big Data Analytics special tool,

including the provisioning of infrastructures services

required for the collection and treatment of data

generated by the experiment.

Smart home and assistive devices integrated with

a software interface. The interface at the patient’s was

modular, timely, easy-to-use, and compatible with all

main existing information systems in Healthcare.

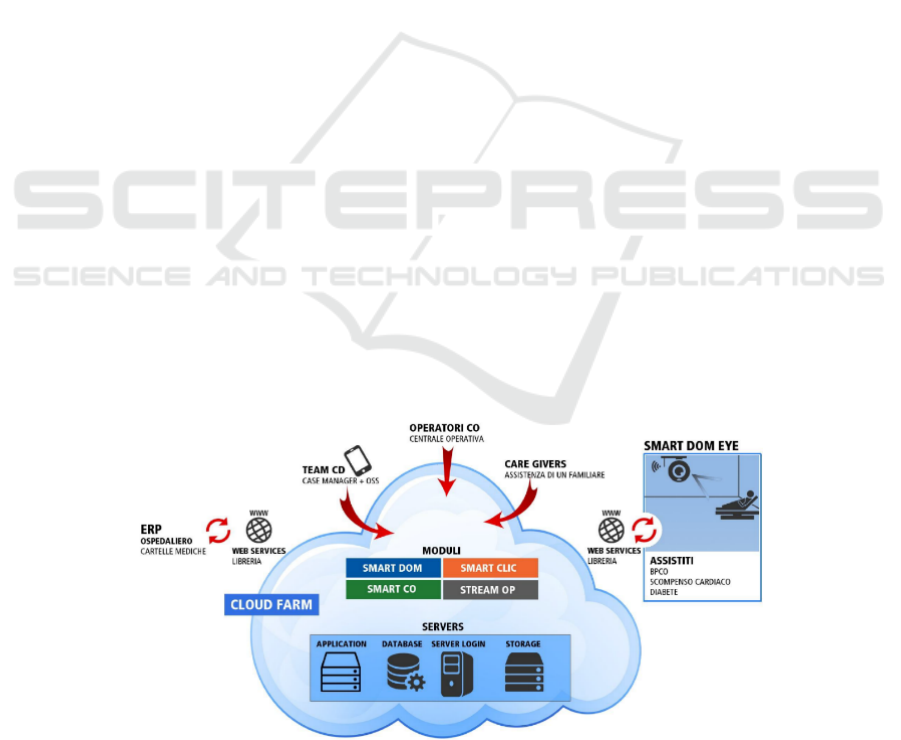

The supporting infrastructure relied on a cost

effective cloud architecture with a multi-channel

access (web, tablet, mobile) by all project

stakeholders (OSS team, case manager, caregivers,

project manager, etc.) to the structured and

unstructured data of the platform. Interconnections

with third parties (ERP HOSPITAL) and FSE

(Electronic Health Record) allowed the possibility, in

addition to reporting, to develop business intelligence

algorithms, when operational, to obtain data and

knowledge on a single practice.

For further reference, we have included, in the

Appendix, Figure 2 depicting the overall set of

components of the technology system used.

3.4 Outcome

The implementation of HaH services reduced the

demand on the resources of the hospitals providing

the same treatment to HaH patients at a lower cost,

availing the resources of the hospital for inpatient

care. Cost savings reported were to the scale of 870 €

per bed per day (for 1 year).

Additionally, patients who participated in the

ADD Protocol have reported better care and better

experience (lessened need to visit the hospital) and

practitioners have expressed better satisfaction due

principally to reduction of their workload. Patients

were empowered to address their issues and in the

comfort of their environment; during the 1-year

timeframe, 89% have reported better access to expert

advice and punctuality in receiving care assistance

and 95% had better hygiene. On the other hand, 93%

of patients reported courteous and pleasant

interaction with their care provider Patients reported

with a higher quality experience overall. Though

initially apprehensive about the use of sophisticated

technologies for care at home, the participants in the

project viewed technology integration as an

unalloyed benefit, as they cherish opportunities to be

with loved ones at home rather than in a hospital, with

the ability to quickly resume a normal life. The

project was deemed a success as it has bolstered the

value of HaH as a viable model of care. As a result,

the ADD project was sanctioned and the local level,

into a set of HaH services.

HEALTHINF 2021 - 14th International Conference on Health Informatics

348

4 REFLECTIONS

As a complex system, the H-SES must be dynamic,

allowing for constant change but minimizing

disruption in the outcome of the services. The

robustness of the system must balance its flexibility

to adapt, reconfigure in the face of changes in the

environment, conditions and constraints.

This is a use case of exploiting technology to re-

configure the Healthcare Service Ecosystem with

structured coordination activities, patient and

caregiver involvement, training of practitioners.

While we can detect the contribution of the usual

suspects in a technology implementation, this study

underscores the importance of aligning to the

quadruple aim of care, health, cost and meaning in

work (Sikka et al, 2015). Patients can progress their

treatment plans outside the hospices of a hospital,

reducing the care burden on the hospital staff,

lowering the risk on the patient’s health and

significantly curbing the cost of care. Our use case

has shown that HaH, when done right, can (1)

Improve effectiveness of care (e.g., lower

readmission rates for heart failure patients); (2)

Reduce the threat of complications, for improved care

outcome; (3) Provide timeliness of care – improving

patient access to care; (4) Increase the satisfaction of

the variety of actors in the system (Patients,

providers, etc.); and (5) Reduce burden and cost on

the Hospitals.

In general, systems thinking studies have

considered variety, variability and uncertainty as

pillars for defining actions and interconnections

among actors. Our use case reinforces this thinking

by introducing examples of adaptation, and re-

configurability.

From the perspective of adaptation, we make

evident how healthcare entities need to change and

update protocols, procedures, operations, by

following local needs, and adapting to physical,

technological and infrastructural constraints. In our

case, the use of technology underscored the

advantage of integrating clinical actions with existing

technical trends and tools. Lessons can be drawn for

the implementation of a wider component of this

ecosystem that solves for the crowding hospitals, in

the seasonal peak of particular diseases, outside the

structural limits of such a traditional hospital

department, in the absence of doctors, medical teams

or other personnel for any reasons.

Another perspective is how the healthcare

ecosystem was reconfigured to deal with the variety,

variability and uncertainty of the conditions in

settings outside the perimeter of the traditional

hospital, taking into account the sustainability of

service provision, the lean management of resources

(including people efforts), and the self-learning

actions to implement the specialized know-how and

skills/competences in care giving.

5 CONTRIBUTION

Grounded in the works of contemporary scholars, this

paper offers valuable insights for future

implementation of similar HaH solutions that align

with the quadruple aim principles. The modular

design of the HaH technical solution was an

important element in its success, demonstrating a real

capacity to solve patient’s problems and chronical

difficulties. The system could be used by patients

with different health conditions, in different setting,

with or without the assistance of caregivers, with

exchangeable modes to make an efficient and high

quality healthcare service. Yet, such

implementations bring forth a set of adoption and

ethical issues to deal with, as addressed hereafter.

Historically, HaH has had faced a number of

ethical, legal and clinical practice issues, at the levels

of data-protection, patients’ privacy, training of

family caregiver, discharge planning, etc. (Arras &

ubler, 1994; Budd et al, 2020). The complexity of the

phenomenon of high-tech home care has exposed

patient data to be available to the occasional user of

the devices at a distance from potential governance

measures, otherwise available inside the hospital

systems. Medical teams have to include in their

decisions patients’ preferences, the agreed upon free

choice paradigm can contrast with hospital proposals,

the digital divide can introduce troubles in terms of

distant treatments, there can be such a problem of

infrastructure constraints, like the accessibility, or

difficulties in sensitization and informed consent.

Other frictions could occur when the service is

experienced effectively, as in the case when the care

at home comes too late as a consequence of previous

errors in diagnosis, or when rapid readmissions are

not possible/practicable.

6 CONCLUSION

In closing, this paper has presented a HaH

implementation use case, testimonial to the fact that,

notwithstanding issues of ethics, politics and policy

ramifications, HaH is a viable system component in a

H-SES. As in the case of any other complex system

Responding to COVID-19: Potential Hospital-at-Home Solutions to Re-configure the Healthcare Service Ecosystem

349

implementation, there has to be a clear definition for

fit for use and fit for purpose.

Our use case was timely and effective in

upholding the principles of the Quadruple Aim. The

unwavering focus on patient experience, improving

their outcome, lowering their risk and creating a

service ecosystem where all actors are satisfied, costs

are controlled and services are rendered effectively.

The project was deemed a success as it has bolstered

the value of HaH as a viable model of care. As a

result, the ADD project was sanctioned and the local

level, into a set of HaH services.

Nowadays, clinicians are leading service

reconfiguration to cope with COVID-19, through

learning new skills, adapting and exploiting new

means of consultations. In other cases, hospitals have

had to reconfigure their health services to reduce the

workload of caregivers during the COVID-19

outbreak. Our use case can be a lesson for the

adaptation of technology for patient empowerment

allowing patients to interact with their care ecosystem

while at their home.

REFERENCES

Al-Balushi, S.; Sohal, A.S.; Singh, J.; Al Hajri, A.; Al Farsi,

Y.M.; Al Abri, R. Readiness factors for lean

implementation in healthcare settings—A literature

review. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2014, 28, 135–153.

Arras, J. D., & Dubler, N. N. (1994). Bringing the hospital

home ethical and social implications of high-tech home

care. The Hastings Center Report, 24(5), S19-S28.

ASME.ORG https://aabme.asme.org/posts/top-6-robotic-

applications-in-medicine

Badr, N. G., Sorrentino, M., & De Marco, M. (2018,

September). Health Information Technology and

Caregiver Interaction: Building Healthy Ecosystems. In

International Conference on Exploring Service Science

(pp. 316-329). Springer, Cham.

Baily, M. A., Bottrell, M., & Lynn, J. (2007). Health care

quality improvement: ethical and regulatory issues. B.

Jennings (Ed.). Hastings Center.

Barile, S., Polese, F., Carrubbo L., “Il cambiamento quale

fattore strategico per la sopravvivenza delle

organizzazioni imprenditoriali”, in S. Barile, F. Polese,

M.Saviano (eds), Immaginare l’Innovazione, pp.1-35,

2012a.

Barile, S., Polese, F., Saviano, M., Carrubbo L. (2016),

“Service Innovation in Translational Medicine”, in

Russo Spena T., Mele C., Nuutinen M. (Eds.),

Innovation in Practices, Perspectives and Experiences,

ed. Springer, pp.417-438, 2016.

Barile, S., Polese, F., Saviano, M., Carrubbo, L., Clarizia,

F. (2012b), “Service Research Contribution to

Healthcare Networks’ Understanding”, in Mickelsson,

J., Helkkulla, A. (eds.), Innovative Service

Perspectives, Hanken School of Economics, Hanken.

Bodenheimer, T.; Lorig, K.; Holman, H.; Grumbach, K.

Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary

care. JAMA 2002, 288, 2469–2475.

Bonadio, B., Huo, Z., Levchenko, A. A., & Pandalai-Nayar,

N. (2020). Global supply chains in the pandemic (No.

w27224). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Breslow, L., “Empowerment, not outreach: serving the

health promotion needs of the inner city”, American

journal of health promotion, vol.7, n.1, p.7, 1992.

Britt, T.W., Castro, C.A., Adler, A.B., “Self-engagement,

stressors, and health: A longitudinal study”, Pers Soc

Psychol Bull, vol.31, n.11, pp.1475-1486, 2005.

Budd, J., Miller, B. S., Manning, E. M., Lampos, V.,

Zhuang, M., Edelstein, M., ... & Short, M. J. (2020).

Digital technologies in the public-health response to

COVID-19. Nature medicine, 1-10.

Sikka, R., Morath, J. M., & Leape, L. (2015). The quadruple

aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work.

Capunzo, M., F. Polese, G. Boccia, L. Carrubbo, F.

Clarizia, and F. De Caro, “Advances in service research

for the understanding and the management of service in

healthcare networks,” Gummesson, E., Mele, C.,

Polese, F. (eds), System Theory and Service Science:

Integrating three perspectives in a new service agenda,

Giannini, Napoli, pp. 14–17, 2013.

Caputo, F. Approccio Sistemico e Co-Creazione di Valore

in Sanità; Edizioni Nuova Cultura: Roma, Italy, 2018.

Carrubbo, L, F. Clarizia, X. Hysa, and A. Bilotta, “New

“smarter” solutions for the healthcare complex service

system,” Gummesson, E., Mele, C., Polese, F.(eds),

System Theory and Service Science: Integrating Three

Perspectives In a New Service Agenda, Giannini,

Napoli, pp. 14–17, 2013.

Carrubbo, L., Bruni, R., Cavacece, Y., Moretta Tartaglione,

A., "Service System Platforms to improve value co-

creation: insights for Translational Medicine", in

Gummesson, E., Mele, C., Polese, F. (eds), System

Theory and Service Science: Integrating three

perspectives in a new service agenda, Napoli, 09-12.

2015.

CDC.ORG - https://cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-

ncov/hcp/telehealth.html

Ciasullo, M. V., Cosimato, S., & Pellicano, M. (2017).

Service innovations in the healthcare service

ecosystem: a case study. Systems, 5(2), 37.

Cohen, S.R.; Hassan, S.A.; Lapointe, B.J.; Mount, B.M.

Quality of life in HIV disease as measured by the

McGill quality of life questionnaire. Aids 1996, 12,

1421–1427.

Finsterwalder, J., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2020).

Equilibrating resources and challenges during crises: a

framework for service ecosystem well-being. Journal

of Service Management.

Frow, P., J. R. McColl-Kennedy, T. Hilton, A. Davidson,

A. Payne, and D. Brozovic, “Value propositions: A

service ecosystems perspective,” Marketing Theory,

vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 327–351, 2014

HEALTHINF 2021 - 14th International Conference on Health Informatics

350

Frow, P., McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Payne, A., & Govind, R.

(2019). Service ecosystem well-being:

conceptualization and implications for theory and

practice. European Journal of Marketing

Grimm CA. Hospital Experiences Responding to the

COVID-19 Pandemic: Results of a National Pulse

Survey March 23–27, 2020. U.S. HHS. OIG.

Gruman, J., Rovner, M.H., French, M.E., Jeffress, D.,

Sofaer, S., Shaller, D., Prager, D.J., “From patient

education to patient engagement: implications for the

field of patient education”, in Patient education and

counseling, vol.78, n.3, pp.350-356, 2010.

Häring, I., Sansavini, G., Bellini, E., Martyn, N.,

Kovalenko, T., Kitsak, M., ... & Linkov, I. (2017).

Towards a generic resilience management,

quantification and development process: general

definitions, requirements, methods, techniques and

measures, and case studies. In Resilience and risk (pp.

21-80). Springer, Dordrecht.

Hwang, J.; Christensen, C.M. Disruptive innovation in

health care delivery: A framework for business-model

innovation. Health Aff. 2008, 27, 1329–1335.

Ignone, G.; Mossa, G.; Mummolo, G.; Pilolli, R.; Ranieri,

L. Increasing public healthcare network performance

by de-hospitalization: A patient pathway perspective,

Strateg. Outsourc. Int. J. 2013, 6, 85–107.

Leff, B. Acute? Care at home. The health and cost effects

of substituting home care for inpatient acute care: A

review of the evidence. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2001, 49,

1123–1125.

Levine, D. M., Ouchi, K., Blanchfield, B., Saenz, A.,

Burke, K., Paz, M., & Schnipper, J. L. (2020). Hospital-

level care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized

controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med., 172(2), 77-85.

Moazzami, B., Razavi-Khorasani, N., Moghadam, A. D.,

Farokhi, E., & Rezaei, N. (2020). COVID-19 and

telemedicine: Immediate action required for

maintaining healthcare providers well-being. Journal of

Clinical Virology, 104345.

Moliner, M.A., “Loyalty, perceived value and relationship

quality in healthcare services”, Journal of Service

Management, vol.20, n.1, pp.76-97, 2009.

P2PH, IHI.ORG; Pathways to Population Health (P2PH) -

http://www.ihi.org/

Polese, F.; Carrubbo, L. Eco-Sistemi di Servizio in Sanità;

G. Giappichelli Editore: Torino, Italy, 2016.

Polese, F.; Carrubbo, L.; Caputo, F.; Sarno, D., “Managing

Healthcare Service Ecosystems: Abstracting a

Sustainability-Based View from Hospitalization at

Home (HaH) Practices”, in Sustainability, pp.1-15.

2018.

Rodríguez Verjan, C.; Augusto, V.; Xie, X.; Buthion, V.

Economic comparison between Hospital at Home and

traditional hospitalization using a simulation-based

approach. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2013, 26, 135–153.

Sofaer, S., Firminger, K., “Patient perceptions of the quality

of health services”, in Annual Review of Public Health,

vol.26, pp.513-559, 2005.

Sweeney, J.C., Danaher, T.S., Mccoll-Kennedy, J.R.,

“Customer effort in value cocreation activities

improving quality of life and behavioral intentions of

health care customers”, in Journal of Service Research,

vol.18, n.3, pp.318-335, 2015.

Thornton, J. (2020). Clinicians are leading service

reconfiguration to cope with covid-19. bmj, 369.

Wilson, M.G. Rapid Synthesis: Identifying the Effects of

Home Care on Improving Health Outcomes, Client

Satisfaction and Health System Sustainability;

McMaster Health Forum: Hamilton, ON, Canada,

2018; 9.

APPENDIX

Figure 2: The new ‘ADD’ flow - From (www.magaldilife.it).

Responding to COVID-19: Potential Hospital-at-Home Solutions to Re-configure the Healthcare Service Ecosystem

351