The Unacceptance of a Self-Management Health System by Healthy

Older Adults

Ine D’Haeseleer

1 a

, Dries Oeyen

2

, Bart Vanrumste

1 b

, Dominique Schreurs

3 c

and Vero Vanden Abeele

1 d

1

KU Leuven, e-Media Research Lab, Belgium

2

BeWell Innovations, Belgium

3

KU Leuven, ESAT-TELEMIC, Belgium

Keywords:

Older Adults, Self-Management Health Systems, User-study, UTAUT Acceptance Model.

Abstract:

Self-Management Health Systems (SMHS) are defined as systems that combine data logging via multiple

sensors and/or self-reports, possibly enhanced with risk assessment and decision support. Research on SMHS

is booming, particularly as it is envisioned to support ageing in place for an increasingly greying population.

However, findings on what drives adoption of SMHS by healthy older adults is still lacking. Therefore, an

SMHS was tested for two weeks in a real world setting by 16 healthy participants aged 65+. We measured

acceptance towards the SMHS pre and post, combined with qualitative data , and usage logs. Results indicate

that at the start of the study, older adults perceived the system as easy to use, useful, and that participants had

access to supporting infrastructure. Notwithstanding, behavioural intention to use an SMHS was rather low.

Post usage, our findings show that, while perceived ease of use and confidence increased, perceived usefulness

and behavioural intention further decreased. These findings suggest that older adults are not yet ready to adopt

SMHS, and that design efforts should particularly be geared towards increasing perceived usefulness.

1 INTRODUCTION

The world’s population is ageing; it is predicted that

the number of people aged 65 years or older will dou-

ble to 160 millions by 2060 (Nations, 2015). There-

fore, many studies focus on older adults and tech-

nologies to support healthy ageing. In particular,

Self-Management Health Systems (SMHS), i.e., inte-

grated technical systems which combine data logging

via multiple sensors and/or self-reports, e.g., surveys,

logbooks, pain scales, with data visualisations, risk

assessment, and decision support, have been put for-

ward as a solution to support ageing in place (Queir

´

os

et al., 2017). Such systems are equally envisioned

to support a shift to preventive care, and to empower

older adults in the co-creation of their own health

(Vines et al., 2015).

Many R&D efforts are geared towards building

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5455-3581

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9409-935X

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4018-7936

d

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3031-9579

SMHS and solving technical challenges (Doyle et al.,

2014; Jim

´

enez-Mixco et al., 2013). Various com-

mercial and non-commercial actors are working on

increasingly efficient technological systems, varying

from memory training (Lumos Labs, 2020) to track-

ing of vital parameters (iHealth Labs Inc., 2019) e.g.,

blood pressure, glucose meters, or any combination.

Besides tracking information, also self-reported data,

e.g., (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992; Fougeyrollas and

Noreau, 2001) and risk assessments, e.g., (Bucking-

ham, 2016) are investigated and used in SMHS.

However, beyond solving technological chal-

lenges, there is also a need for further insight into

the actual use and acceptance of these systems, and

what drives adoption of SMHS by older adults. Stud-

ies on the adoption of related technologies for e.g.,

assisted living or telemonitoring show mixed results.

Some studies (Sintonen and Immonen, 2013; Wang

et al., 2019) show that older adults are open to the

idea of managing their own health. Other studies por-

tray a more nuanced image on acceptance of health-

related ICT among older adults (Heart and Kalderon,

2013; Peek et al., 2016; Young et al., 2013; Verdezoto

D’Haeseleer, I., Oeyen, D., Vanrumste, B., Schreurs, D. and Abeele, V.

The Unacceptance of a Self-Management Health System by Healthy Older Adults.

DOI: 10.5220/0009806402690280

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2020), pages 269-280

ISBN: 978-989-758-420-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

269

and Gr

¨

onvall, 2016; Jaschinski and Allouch, 2015;

Kononova et al., 2019; D’Haeseleer et al., 2019b).

These studies indicate a lack in perceived usefulness

and identify remaining barriers which needs to be ad-

dressed before adoption of SMHS by older adults.

These inconsistent findings may be due to different

operationalisations of what constitutes SMHS. They

may also be attributed to different inclusion criteria

for older adults, or different contexts-of-use – mun-

dane versus clinical contexts (Nunes et al., 2015).

Due to the inconsistent findings, designers may

lack insight into what drives the acceptance and use

of SMHS by older adults, and how to design for it.

In this study, we are particularly interested in com-

munity dwellers who aim to use SMHS in a mun-

dane setting, i.e., older adults aged over 65+, in good

health and still living at home. We deemed it impor-

tant to gain a deeper understanding of how this group

of older adults uses SMHS by combining quantitative,

qualitative, and usage data.

Therefore, we created a prototypical SMHS, in-

cluding a questionnaire on health and wellbeing, an

activity tracker, a blood pressure monitor, and a sleep

sensor. After designing and developing the SMHS,

the application was tested in a real world setting by

means of a user-study with 16 self-reported healthy

1

participants aged 65+, during two weeks. Acceptance

of the SMHS was both measured at the beginning and

at the end of the user-study, based on a questionnaire

informed by the Unified Theory of Acceptance and

Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Additionally, extra information was collected through

open-ended interviews and usage logs. The results

suggest a lack in intention to adopt the SMSH; older

adults aged 65+ are not yet waiting for these systems.

In Section 2, an overview of related work is given.

Section 3 describes the method. Section 4 presents

participants’ results: experience data, UTAUT evalu-

ation, and usage data. Further, in Section 5 results are

discussed and compared to findings in literature. Fi-

nally, section 6 concludes and addresses future work.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Self-Management Health Systems

SMHS are on the rise. Several researchers investi-

gated the acceptance and use of SMHS by older adults

(Sintonen and Immonen, 2013; Heart and Kalderon,

1

Older adults that perceive themselves as healthy, but

may experience mild cognitive and/or physical decline due

to their age.

2013; Peek et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). Often,

such studies include hundreds of participants, to al-

low generalising views and attitudes of the partici-

pants to a broader audience of ‘older adults’. Yet,

such survey studies most often remain hypothetical,

as participants are not offered a salient experience of

using an actual SMHS. On the other hand, studies

that do include hands-on experiences through work-

shops or prototypes, e.g., (Kononova et al., 2019;

D’Haeseleer et al., 2019b; Jaschinski, 2014; Verde-

zoto and Gr

¨

onvall, 2016; Young et al., 2013) are

mainly system evaluations that gauge technical pos-

sibilities, as well as usability issues. These studies

are highly important to overcome possible barriers in

developing and using SMHS, but not well suited to

understand and evaluate long-term adoption.

Adoption studies with older adults do exist, but

are typically not using SMHS, but rather a related

ICT technology, or rely on the support of a care-

giver. For example, Jim

´

enez-Mixco et al. investi-

gated a system to monitor health and promote ac-

tive ageing by including biomedical sensors in over

100 healthy older adults (Jim

´

enez-Mixco et al., 2013).

Results were promising regarding usability and use-

fulness, and moreover, most of the participants (68%)

wanted to use the application in the future. However,

older adults in this study were relatively young (aged

55+). Moreover, the study did not focus on the self-

managing of health, as they still relied on the support

of a caregiver. Another study from McMahon et al.

investigated the use and acceptance of older adults,

aged 70+, towards physical activity trackers (McMa-

hon et al., 2016). In total, 95 older adults participated

in an intervention study of 8 months. At the end of

the study, participants were asked about their experi-

ences. Ratings were twice positive, nevertheless, they

did decrease in the second measurement. Researchers

also found that the oldest older adults (80+) were less

positive than those aged between 70 and 80.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is

only one adoption study on using SMHS by older

adults. Doyle et al. investigated attitudes and ad-

herence to wellness self-management in older adults

(Doyle et al., 2014). The sample was limited to seven

participants (mean age=70.6), who tested the applica-

tion. After two months the trial period was over and

participants were free to continue or quit using the

application (one person quit). After five months, par-

ticipants were interviewed to learn about their experi-

ences. Results showed that the application was found

user-friendly, and participants were intrinsically mo-

tivated to use it. Participants particularly emphasised

the importance of receiving feedback from the sys-

tem.

TEG 2020 - Special Session on Technology, Elderly Games

270

2.2 Technology Acceptance Theories

There are several psychological theories that inves-

tigate user acceptance and adoption of technologies,

e.g., (Champion et al., 2008; Fishbein, 1979; Deci

and Ryan, 2012; Davis, 1985; Venkatesh et al., 2003).

The model underlying this study is the “Unified the-

ory of acceptance and use of technology” (UTAUT)

(Venkatesh et al., 2003). This model has been put

forward as the gold standard of technology adoption

(Taiwo and Downe, 2013). UTAUT was first used in

general IT adoption within a work environment. Yet

since, several studies have used and extended UTAUT

to health care technologies, e.g., (Peek et al., 2019;

Vanneste et al., 2013; Khechine et al., 2016; Cimper-

man et al., 2016), and portrayed it as a fitting theory

also in a health care context. According to UTAUT,

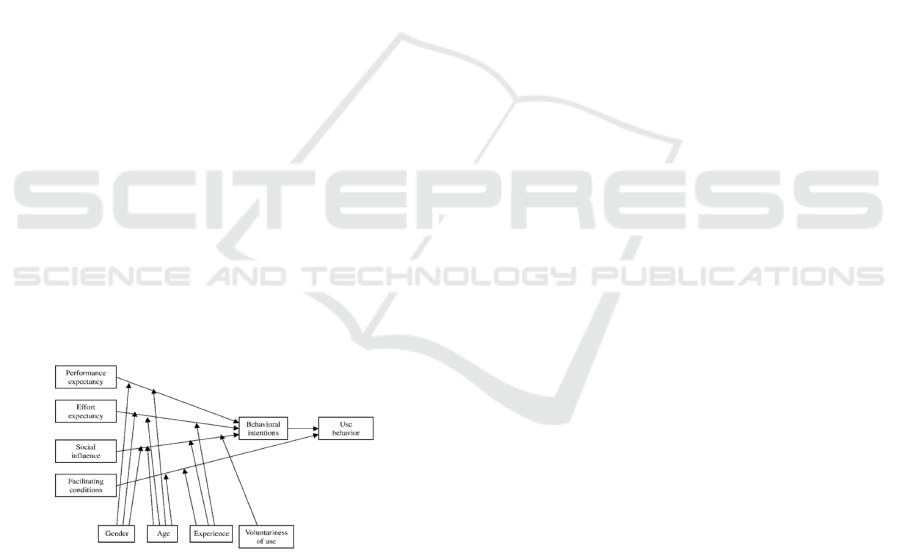

four key constructs are used to assess behavioural in-

tention (i.e., acceptance) to use a system:

1. Performance Expectancy (PE) or “Do I find the

system useful?”

2. Effort Expectancy (EE) or “How difficult do I find

it to use the system?”

3. Social Influence (SI) or “What will others think

about me when using the system?”

4. and Facilitating Conditions (FC) or “Do I have the

facilities/technologies in order to use the system?”

The UTAUT model upholds that these constructs

are determinants of the behavioural intention to use

the system and can be used to predict the actual use

(see figure 1). In other words, by measuring these four

constructs, one can predict the Behavioural Intention

(BI) of the user to adopt, and use the system.

Figure 1: UTAUT model by (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

However, most recent studies focusing on adop-

tion of health care technologies that involve captur-

ing data from users, by means of sensors and/or self-

reports, showed that additional constructs such as

‘anxiety’ or ‘safety of data’ may also play an impor-

tant role in the use and acceptance of technologies

(Ebert et al., 2015; Baumeister et al., 2014). Hence,

in more recent UTAUT models for a health care con-

text, these constructs can be added (De Witte and

Van Daele, 2017).

3 METHOD

To explore the attitudes of older adults towards one

particular SMHS, we conducted a user evaluation

with 16 participants (ten women and six men) for a

two-week study. These studies took place between

July and November 2018.

3.1 SMHS Application with Sensors

For this study, an application was designed for older

adults to fill out questionnaires, view their answers to

the questionnaire’s items, along with results measured

by three different sensors: activity tracker, sleep mon-

itor, and blood pressure monitor.

The questionnaire used in this study is a combi-

nation of the RAND-36 (Ware and Sherbourne, 1992;

Van der Zee and Sanderman, 1993) and Life Habits

(Fougeyrollas and Noreau, 2001; Lemmens et al.,

2007). RAND-36 is an assessment for health-related

quality of life, divided over nine categories: physi-

cal functioning, physical role functioning, emotional

role functioning, energy/fatigue, emotional wellbe-

ing, social functioning, pain, general health, and

health change. The RAND questionnaire was vali-

dated with 8117 community dwellers, ages ranging

from 65-104 years old (Walters et al., 2001). Data

was reported and made it possible to filter for gender

and age-group, and therefore was used as an indica-

tion for ‘other’ participants. For our application, addi-

tionally, three categories were selected from the Life

Habits: meals, sleep, and personal care. Thus in total,

our SMHS consisted of 12 categories and 49 items.

The application was developed as a web-

application, optimised for tablet-use. The preferred

design needed to be as simple as possible, thus lim-

iting the amount of features available. When using

the application, the home screen gives an overview of

the results from the activity tracker and the question-

naires. Participants can select a topic from a question-

naire and fill out several questions. Once a category

is completed, results are shown on the results page,

where participants can also compare themselves to

normalised data from a previous study (Walters et al.,

2001). The results from the sensors are automatically

synchronised with the application and can be viewed

on a different screen. Different screenshots of the ap-

plication are shown in figure 2.

The sensors, which were integrated in the appli-

cation, consist of an activity monitor (Activ8, 2016),

a sleep monitor (Beddit, 2016), and a blood pressure

monitor (A&DCompany, 2016). The activity tracker

can be worn in a pocket of trousers and distinguishes

activities such as ‘lying down’, ‘standing’, ‘sitting’,

The Unacceptance of a Self-Management Health System by Healthy Older Adults

271

(a) Overview page.

(b) Question in questionnaire.

(c) Results from questionnaires.

(d) Results from sensors.

Figure 2: Screenshots of SMHS application.

‘walking’, ‘cycling’, and ‘running’. The sleep moni-

tor registers how long someone sleeps, as well as the

efficiency of the sleep represented by a sleep score.

The blood pressure monitor captures the systolic and

diastolic pressure as well as the pulse. Data from the

sensors were collected via BeWell Innovations (Inno-

vations, 2016) and automatically, through an API, in-

tegrated and visualised in the SMHS.

(a) Activ8

activity tracker.

(b) Beddit sleep

monitor.

(c) A&d blood

pressure monitor.

Figure 3: Integrated sensors in SMHS.

3.2 Measurement Instrument

To measure use and acceptance of the SMHS, we re-

lied on the Dutch variant of the questionnaire based

on Ebert et al. (Ebert et al., 2015), translated by De

Witte and Van Daele (De Witte and Van Daele, 2017).

This Dutch questionnaire polls for seven drivers: per-

formance expectancy (PE), effort expectancy (EE),

social influence (SI), facilitating conditions (FC),

anxiety (ANX), safety (SAF), and behavioural inten-

tion (BI). Minor adjustments were made to the items,

included changing ‘technology’ to ‘SMHS’, and ‘psy-

chological problems’ to ‘perceived self-reliance’. The

full list of all questions can be found in table 2. In to-

tal, the questionnaire consisted of 25 items to be an-

swered on a 5-point-Likert scale, were 1 represents

‘totally disagree’, and 5 represents ‘totally agree’,

thus 3 indicating ‘neither agree nor disagree’. All re-

sults were analysed via SPSS (IBM, 2017).

3.3 Participants

Participants were first contacted based on their indi-

cated interest in a previous study (D’Haeseleer et al.,

2019b). As only two of them were interested in par-

ticipating, further recruitment was carried out via the

snowball sampling method (Biernacki and Waldorf,

1981). Inclusion criteria stated that participants were

above 65 years old, living independently at home or

in a service flat, and not suffering from medical con-

ditions that required specific clinical supervision. The

study was approved by the Social and Societal Ethics

Committee (G-S60250).

3.4 Procedure

Before starting the study, the researcher (first author)

visited the older adults in their homes. She described

the study design, and explained the information in the

informed consent. Participants were able to ask ad-

ditional questions, and the researcher always had a

TEG 2020 - Special Session on Technology, Elderly Games

272

Table 1: Demographic and experience information on participants. Information of the wearables are indicated as activity

(ACT), blood pressure monitor (BPM), and heart rate monitor (HRM).

Experiences with

code gender age living area tablet computer smartphone wearables owning wearables

P01 female 67 home with partner few few none none none

P02 male 69 home with partner little little none none none

P03 male 66 home with partner little little few a lot ACT, HRM

P04 male 80 home little little little none none

P05 female 82 flat few few few none BPM

P06 female 71 home with partner few little none none BPM

P07 female 84 flat few little little none BPM

P08 female 78 flat none few few none BPM

P09 female 66 home with partner a lot few a lot none BPM

P10 female 74 home with partner none little none none none

P11 male 76 home with partner none a lot none none none

P12 male 66 home with partner none little few little BPM, ACT

P13 female 75 home none none none little BPM

P14 female 86 flat little little little none BPM

P15 male 84 home with partner a lot a lot a lot none BPM, ACT

P16 female 71 home with partner few a lot a lot none BPM

tablet and one set of sensors with her, to show these

to the participants.

Once someone agreed on participating in this

study, a suitable starting date was chosen. This var-

ied from starting the same day to one month later, de-

pending on the availability of the participants and the

schedule of the researcher. On the starting day, par-

ticipants received a tablet with the web-application,

along with the sensors. The researcher installed ev-

erything and showed the participants how to interact

with the sensors and the application. Additionally,

every participant was asked to conduct each task at

least once, in order to get familiar with the technolo-

gies. Afterwards, participants were asked to fill out

the UTAUT questionnaire for the first time (PRE).

This evaluation polls for the users expectations of this

SMHS.

Participants were asked to fill out a questionnaire

at least every three days, and to use the sensors daily.

The experiment lasted for two weeks. The researcher

called the participant after one day, in order to check

up on their experiences. Depending on the needs of

the participant, the researcher made more frequent

visits (this varied from only at the start and end of the

study, to multiple times a week). Participants could

always call the researcher when they needed extra

support.

Finally, after two weeks had passed, the researcher

went back to the participant’s home, and a second

UTAUT questionnaire was taken (POST). In addition,

a semi-structured interview was conducted where par-

ticipants were asked about how they perceived using

wearable sensors, and whether they were interested in

using wearable sensors in the future. Moreover, the

researcher also briefly asked participant about their

overall experiences, what they liked and disliked.

4 RESULTS

In this section, we first present the results of the

UTAUT questionnaire, alongside relevant excerpts

from post-hoc interviews and observations. An

overview of all individual UTAUT items, along with

an overview of mean scores for each construct, Cron-

bach’s alpha, and mean difference can be found in ta-

ble 2. Next, we detail the data from the usage logs.

4.1 Participants and Experience Data

In total, 16 participants (median age = 74.5) were re-

cruited. Detailed information about the participants

can be found in table 1. As expected, participants had

never used an SMHS before. Five participants had

little to no experience with using a computer, ten par-

ticipants had little experience to no experience using a

tablet before, and six participants never used a smart-

phone.

4.2 Evaluation UTAUT Constructs

For each of the seven constructs, a reliability analysis

(by means of Chronbach’s alpha) was performed. Re-

sults of the average scores together with all individual

The Unacceptance of a Self-Management Health System by Healthy Older Adults

273

Table 2: UTAUT constructs and questions. All reversed items are marked with an asterix (

∗

).

Cronbach’s

Alpha

Mean (SD)

Code Construct and Item PRE POST PRE POST

EE Effort Expectancy .846 .789 3.18(.915) 3.79(.939)

EE

1

The SMHS was clear and easy to understand. 3.50(1.03) 4.06(1.29)

EE

2

Using the SMHS seems simple. 3.38(1.15) 4.00(1.16)

EE

∗

3

Using the SMHS seems complicated. 2.94(1.34) 3.62(1.50)

EE

∗

4

Before I can/could use the SMHS, I still need/had to

learn a lot.

2.13(1.09) 3.19(1.38)

EE

5

I have sufficient technological knowledge (turning on/off

and charging the devices) to use the SMHS.

3.94(1.18) 4.06(.998)

PE Performance Expectancy .891 .927 3.75(.957) 3.14(1.37)

PE

1

Using the SMHS would increase my perceived self-

reliance.

3.88(1.15) 3.19(1.38)

PE

2

Using the SMHS would increase my personal wellbeing. 3.63(1.03) 3.13(1.41)

PE

3

The SMHS would increase my confidence to live inde-

pendently.

3.63(1.20) 3.31(1.62)

PE

4

Using the SMHS would help me to age in place. 3.88(1.03) 2.94(1.61)

SI Social Influence .517 .574 3.72(.730) 3.28(.894)

SI

1

If people in my care networks would know this SMHS,

they would be positive about it.

3.87(.885) 3.38(1.15)

SI

2

It people in my care network would know this SMHS,

they would advise me to use it.

3.56(.892) 3.19(.981)

FC Facilitating Conditions .880 .679 4.06(1.29) 4.03(1.10)

FC

1

I own a computer or tablet, and could therefore use this

SMHS.

3.81(1.52) 3.88(1.41)

FC

2

I have a reliable internet connection. 4.31(1.20) 4.19(1.11)

ANX

∗

Anxiety .536 .877 3.31(1.34) 3.56(1.37)

ANX

∗

1

I am afraid to make an irrevocable mistake when using

the internet.

3.31(1.62) 3.88(1.31)

ANX

∗

2

The internet sometimes feels like something threatening. 3.31(1.62) 3.25(1.57)

SAF Safety .357 .774 4.31(.911) 3.66(1.30)

SAF

∗

1

I am afraid that confidential information will fall into the

wrong hands.

3.81(1.56) 3.13(1.71)

SAF

2

I am confident that when I use the SMHS, that all infor-

mation will be treated strictly confident.

4.81(.544) 4.19(1.11)

BI Behavioural Intention .828 .804 2.86(.992) 2.55(1.13)

BI

1

I would recommend the SMHS to others (older adults),

when they are still living independent at home.

3.87(.957) 3.75(1.29)

BI

2

I would like to use this SMHS in the future. 3.44(1.37) 2.50(1.367)

BI

3

I would purchase this SMHS, if this would be commer-

cially available.

3.00(1.21) 2.44(1.41)

BI

4

How often do you think you would use this SMHS in the

future. (1: never, 2: once a month, 3: once a week, 4:

twice or three times a week, 5: every day)

1.13(1.31) 1.50(1.59)

TEG 2020 - Special Session on Technology, Elderly Games

274

items are pictured in table 2. Results indicate that be-

fore starting the experiment, participants were neutral

to positive towards using an SMHS. When analysing

the results after the study, scores slightly decreased

for all constructs, except for effort expectancy. Below,

all constructs and average ratings, along with quotes

from the interviews, are given.

Effort Expectancy. EE initially scored an average

of 3.18 (SD=0.92) (on a scale from 1 to 5), thus

close to neutral. After the study, this score increased

to 3.79 (SD=0.94), indicating that older adults’ per-

ceived ease of use increased after the two-week study.

These scores are in line with observations from the

researcher who made the house visits. It was often

noticed that at first, participants were afraid of hav-

ing to use the tablet. However, after going through

the application together, participants managed to use

it independently.

P05: “In the beginning it is a bit overwhelm-

ing, but once you use it, it all goes very well.”

(day 2)

Performance Expectancy. PE scored initially 3.75

(SD=0.96) out of 5, thus neutral to positive, but after

the study this construct scored only 3.14 (SD=1.4),

hence it decreased to a neutral score. This indicates

that older adults found the application more useful at

the beginning of the study compared to after using it

for two weeks. Overall, participants found it interest-

ing to follow up on their own health. Especially when

using the sensors, often participants mentioned they

gained new insights, and where happy to learn more

about their activity, blood pressure, and/or sleep.

P16: “It is striking to see how much you sit

down every day. Interesting to follow up on.”

(day 8)

Some participants were just curious, and did not feel

the need to keep on using these sensors for a longer

period.

P05: “I found it interesting to follow up on my

sleep patterns. I was already familiar with my

activities and blood pressure. But now I know,

so I would not keep on using it.” (day 14)

The blood pressure monitor was already used in ad-

vance by most participants. Others, who did not regu-

larly take their blood pressure also indicated that they

found it interesting to follow up. Although one person

also reported that ambivalence, since noticing your

blood pressure is too high can also make you worried.

P01: “I would find blood pressure measure-

ment interesting, but because I have had a

higher [cf. blood pressure] all day, it was

rather worrying me.” (day 13)

Social Influence. SI scored initially 3.72 (SD=0.73)

out of 5, thus neutral to positive, but after the

study this construct decreased to 3.28 (SD=0.89).

Participants often mentioned they did not really know

what their friends/family or physicians would think

about using such an SMHS, as this was never been

discussed.

Facilitating Conditions. FC scored initially

4.06 (SD=1.3) out of 5, thus positive, and after

the study this construct scored still positive with

4.03 (SD=1.1). This is normal as the facilities of

the person’s home have not changed during the

experiment. Almost every participant had access

to either a tablet or a computer, although many of

them did not use these. Also a wireless internet

connection was often available at the participants’

home, however, they had little knowledge on how this

could be accessed. Luckily, in this study, mobile data

cards were implemented in the tablets, so the tablet

and sensors did not need to be attached to the network.

Anxiety. ANX scored initially 3.31 (SD=1.3)

out of 5, thus neutral to positive, but after the study

this score increased to 3.56 (SD=1.4). Note that

items from this construct were reversed, thus a more

positive response indicates that participants were

less anxious towards using the internet. Overall,

participants did not reported anxiety towards using

the internet. However, we noticed that on the first

day, participants were often afraid when using the

tablet. Therefore, it was very important to take time

to comfort them and let them understand they cannot

do anything wrong.

P01: “So I just need to do this [cf. take blood

pressure with a blood pressure monitor] and

then I actually do not need to touch this [cf.

tablet]? [...] I am not going to use that [cf.

tablet].” (day 1)

P04: “I am afraid to do something wrong, or

to forget something.” (day 1)

Safety. SAF scored initially 4.13 (SD=0.91) out of 5,

thus positive, but after the study this construct scored

3.66 (SD=1.3) which is neutral to positive. Nobody

had problems with sharing this sensitive information,

as this was a research study. In this study, privacy

issues from commercial systems were not explicitly

discussed, but in one interview the participant men-

tioned that she had no problem in sharing information,

The Unacceptance of a Self-Management Health System by Healthy Older Adults

275

as this was already also the case with smartphones (cf.

Android from Google) and online advertising.

P09: “Privacy? I have no problems with pri-

vacy. Then you should look at Google and all

their advertising.” (day 15)

Behavioural Intention. BI scored initially 2.86

(SD=0.99) out of 5, thus negative to neutral, but after

the study this construct scored only 2.55 (SD=0.94),

meaning it further decreased. Participants did utter to

find the application useful, however, it was mentioned

multiple times that they would not (yet) need it them-

selves, as they were still in good health.

P09: “Those questionnaires in particular can

be of interest to single elderly people [cf. she

is still living together with her husband]. Cer-

tainly if that would be mandatory and the

physicians also support it.” (day 15)

Participants quickly got used to the application and

the sensors. Using the sensors became a habit for

most of them. At the same time, at the end of the

study, some mentioned they would “not be missing

the sensors”.

P05: “It went very quickly to get used to the

sensors. However, this system is not for me, I

do not need it yet. Moreover, I would rather

not become a ‘slave’ of all those devices.”

(day 14)

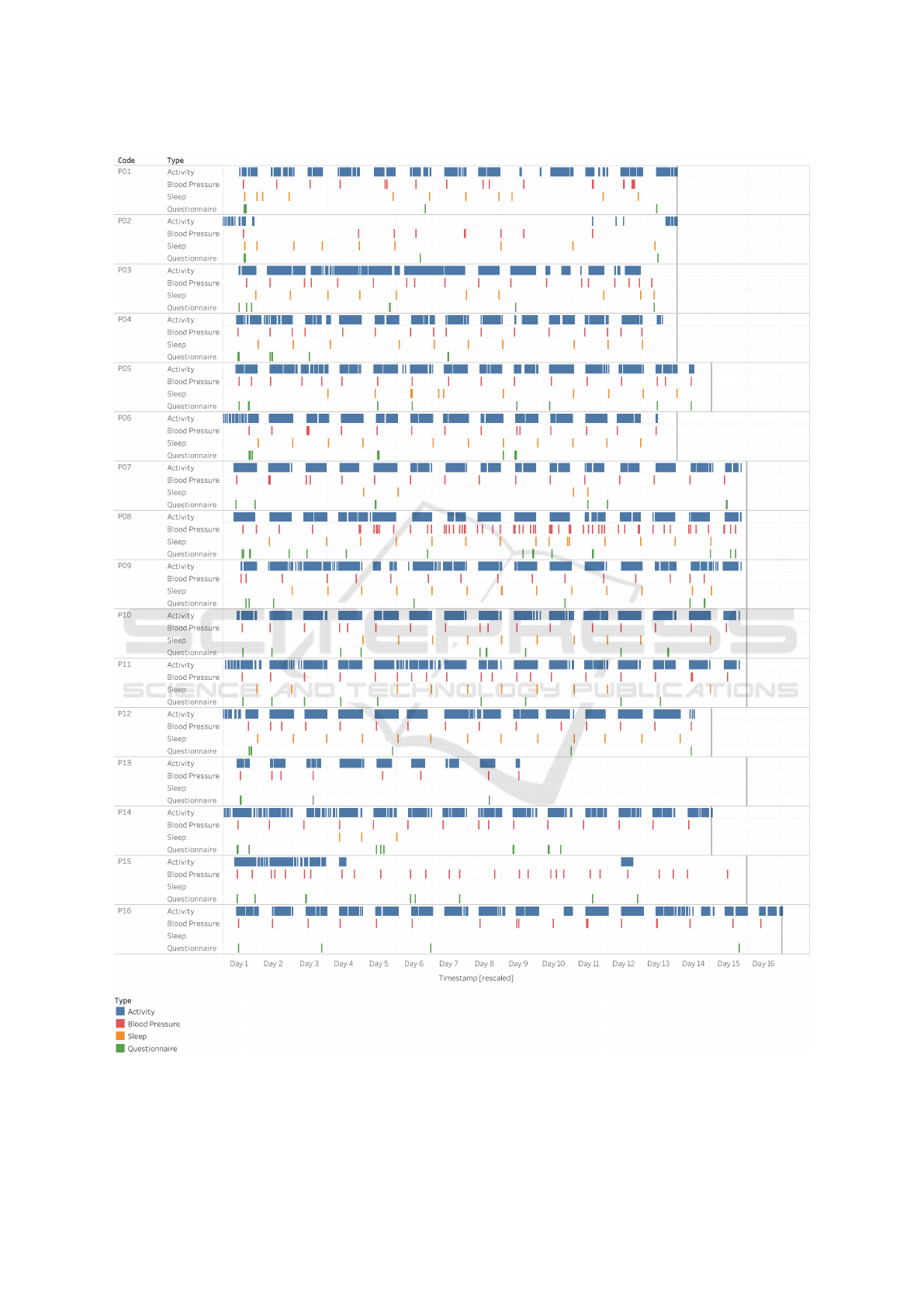

4.3 SMHS Usage Data

Each participant used the application during a two-

week study, varying from 13 to 16 days, depending on

the availability of the person. Participants were asked

to wear an activity tracker every day, to measure their

blood pressure at least once a day, and to use a sleep

monitor every night. Figure 4 gives an overview of

how participants interacted with the SMHS. Note that

all data has been rescaled to the same period, to in-

crease readability. In addition, for each person, a gray

line indicates the exact length of participation in the

study. For each participants, all sensor and/or ques-

tionnaire interactions are pictured.

Questionnaires. Since every participant was asked to

complete a full set of questionnaires (12 categories)

every three days, and to use the sensors daily, ide-

ally this would result in five complete sets, totaling

60 categories. This was only achieved by one par-

ticipant (P08). In contrast, participant P13 quit after

eight days, completing only nine categories. Four par-

ticipants stopped filling out questionnaires after seven

to ten days, the other twelve participants completed

between 36 and 52 categories throughout the entire

study period. Data results, aggregated over all partic-

ipants, show that each category was completed 53 to

68 times throughout the two week study period. In or-

der of importance, the following categories were an-

swered most frequently: emotional role functioning,

sleep, social functioning, mental health, and meals.

Activity Tracker. The activity tracker was used by

15 out of 16 participants. Figure 4 represents a time-

line of participants’ activities, i.e., walking, cycling,

running, sitting, or standing, where at least one ac-

tivity was measured during a five-minute block. The

gaps during the night indicate that participants were

not wearing their tracker when they were sleeping.

From all participants, one person (P01) did not wear

an activity tracker, as she felt her outfit did not al-

low to attach the sensor. Two participants (P02, P15)

stopped wearing the tracker for at least a week within

the study, and one participant (P13) only wore the

tracker for ten consecutive days. Presumable these

participants forgot to charge the battery. The other 12

participants wore the activity tracker daily.

Sleep Monitor. The sleep monitor was used by 14 out

of 16 participants. One participant (P13) was afraid

of using the sleep monitor during the night as she also

had an electrical blanket on top of the mattress and

therefore excluded this sensor. Another participant

(P16) preferred not to use the sleep monitor. The other

participants used the sleep monitor, if possible, as of-

ten participants reported troubles getting data out of

the sensor. Because the support for the type of sleep

monitor used in this study, ‘Beddit’ (Beddit, 2016),

was discontinued, problems occured when pairing the

device. For the first six participants, the sleep moni-

tor was either disfunctional or taken away for replace-

ment, indicating one to three nights without measure-

ments. For participant P07, 10 out of 14 nights, the

sleep monitor was disfunctional. For participant P09

to P12 the sleep was not registered during one to five

nights. While testing with participants P14 and P15,

the integration between the sensors and the platform

was disfunctional and therefore did not register for re-

spectively 11 and 14 days.

Blood Pressure Monitor. The blood pressure mon-

itor was used by all participants. Since some extra

measurements were due to an error in the syncing

process, the measurements that were taken within 5

min of each other were excluded in this analysis. One

participant (P13) only used the blood pressure mon-

itor eight times. This was due to the inability of the

person to attach the strap of the measurement device

TEG 2020 - Special Session on Technology, Elderly Games

276

Figure 4: Usage data from all participants during the two-week experiment.

The Unacceptance of a Self-Management Health System by Healthy Older Adults

277

by herself. Therefore, measurements were only taken

when an additional visitor came by. Participant P08

was an exception, as she took her blood pressure 69

times during the 15 days. In general, on average, par-

ticipants took their blood pressure one to two times a

day.

5 DISCUSSION

This study aimed to investigate whether healthy com-

munity dwellers, aged 65+, were ready to adopt an

SMHS in a real-world home environment. Prior to use

all determinants of use and acceptance of SMHS in

our study were neutral to positive: effort expectancy

(EE), performance expectancy (PE), social influence

(SI), facilitating conditions (FC), anxiety (ANX), and

safety (SAF). Post use, all values (except for EE and

FC) decreased. Moreover, post use, older adults’ be-

havioural intention (BI) scored only an average score

of 2.55 (SD=1.1).

Reflection on SMHS. Our findings contrasts with the

study from Doyle et al. (Doyle et al., 2014), which

is perhaps most akin to our study setup. Several hy-

potheses can be put forward. This may be due to the

specific SMHS design. This may also be attributed

to the use of a different methodology in polling for

adoption. Finally, the different results may also be

due to the fact that the average age of participants in

our study is older. Studies suggest the older the par-

ticipants, the less motivated they are to use interac-

tive health technologies such as a tracker (McMahon

et al., 2016). Similar to Doyle’s findings, however, we

found that older adults like to have freedom in per-

sonalisation, in our case determining which health-

related themes they find interesting.

Reflection on UTAUT Model. In this study, we

relied on the theoretical model of Venkatesh, et al.

(Venkatesh et al., 2003) in order to predict technology

acceptance. This UTAUT model suggests that mea-

surements on the constructs EE, PE, FC, and SI pre-

dict BI, in particular, positive scores on the aforemen-

tioned drivers should also result in a positive score for

BI. Surprisingly, this was not confirmed in our results.

Research from Peek et al. may provide extra insights,

as they investigated motivators for older adults in or-

der to use (new) technologies, as well as impact of

changes and stability of use (Peek et al., 2016; Peek

et al., 2017; Peek et al., 2019). This Cycle of Tech-

nology Acquirement by Independent-Living Seniors

(C-TAILS) model gives an overview of many differ-

ent influential factors in technology adoption by older

adults, including the importance of support by friends

or family, which is weighted strongly. This is in line

with our findings, as the construct social influence

from friends/family or physicians scored rather low

(neutral) post use.

Similar findings were also reported in

(D’Haeseleer et al., 2019a), where authors found

that older adults lack the perceived value of SMHS,

and did not welcome the accompanying shift from

curative to preventive care (Vines et al., 2015). Here,

authors emphasised that older adults will not use

SMHS, or interactive technologies in general, unless

they find it irrefutably useful. This finding is echoed

in this study, as older adults did mention to find the

SMHS useful (PE), but simply not for them. They did

not (yet) see the benefits of using SMHS themselves.

6 CONCLUSION

In this study, we report on the uses and attitudes of 16

healthy participants aged over 65. During a two week

study, participants used an SMHS in a real world set-

ting, at home. An adapted version of Unified The-

ory of Use and Acceptance for Technology (UTAUT)

was used to measure acceptance, both pre and post,

towards an SMHS (De Witte and Van Daele, 2017;

Venkatesh et al., 2003). In addition, usage data was

explored, as well as a post-hoc interview with the par-

ticipants. Results indicate that participants did find

the application user-friendly and felt confident in us-

ing the application. They also had access to a com-

puter or tablet with internet access. Despite these

positive aspects, they did not see the benefits of fol-

lowing up on their own health regularly, and their

behavioural intention decreased even more after the

two-week study.

However, only one SMHS was tested in this study,

with a limited sample. Therefore, future research is

needed to investigate whether these results can be

generalised to other SMHS, and a broader group of

older adults aged 65+.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all users for their participa-

tion. This research study was possible with the sup-

port of KIC EIT funding for GRACE-AGE.

TEG 2020 - Special Session on Technology, Elderly Games

278

REFERENCES

Activ8 (2016). Activ8 Professional validation - Ac-

tiv8all.com.

A&DCompany (2016). Clinical Validation | Medical |

Products | A&D.

Baumeister, H., Nowoczin, L., Lin, J., Seifferth, H., Seufert,

J., Laubner, K., and Ebert, D. D. (2014). Impact of

an acceptance facilitating intervention on diabetes pa-

tients’ acceptance of internet-based interventions for

depression: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes

research and clinical practice, 105(1):30–39.

Beddit (2016). Beddit Sleep Tracker.

Biernacki, P. and Waldorf, D. (1981). Snowball sampling:

Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling.

Sociological methods & research, 10(2):141–163.

Buckingham, C. D. (2016). GRiST - Galatean Risk and

Safety Tool.

Champion, V. L., Skinner, C. S., et al. (2008). The health

belief model. Health behavior and health education:

Theory, research, and practice, 4:45–65.

Cimperman, M., Bren

ˇ

ci

ˇ

c, M. M., and Trkman, P. (2016).

Analyzing older users’ home telehealth services

acceptance behavior—applying an extended utaut

model. International journal of medical informatics,

90:22–31.

Davis, F. D. (1985). A Technology Acceptance Model

for Empirically Testing New End-user Information

Systems: Theory and Results. Massachusetts Insti-

tute of Technology, Sloan School of Management,

https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/15192. Google-

Books-ID: hbx8NwAACAAJ.

De Witte, N. and Van Daele, T. (2017). Vlaamse UTAUT-

vragenlijst.

Deci, E. L. and Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination

theory. Handbook of theories of social psychology.

D’Haeseleer, I., Gerling, K., Schreurs, D., Buckingham,

C., Abeele, V., et al. (2019a). Uses and attitudes of

old and oldest adults towards self-monitoring health

systems. In Pervasive Health, Date: 2019/05/20-

2019/05/23, Location: Trento, Italy.

D’Haeseleer, I., Gerling, K., Schreurs, D., Vanrumste, B.,

and Vanden Abeele, V. (2019b). Ageing is not a dis-

ease: Pitfalls for the acceptance of self-management

health systems supporting healthy ageing. In The 21st

International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Com-

puters and Accessibility, pages 286–298. ACM.

Doyle, J., Walsh, L., Sassu, A., and McDonagh, T.

(2014). Designing a Wellness Self-management Tool

for Older Adults: Results from a Field Trial of

YourWellness. In Proceedings of the 8th Interna-

tional Conference on Pervasive Computing Technolo-

gies for Healthcare, PervasiveHealth ’14, pages 134–

141, ICST, Brussels, Belgium, Belgium. ICST (In-

stitute for Computer Sciences, Social-Informatics and

Telecommunications Engineering).

Ebert, D. D., Berking, M., Cuijpers, P., Lehr, D., P

¨

ortner,

M., and Baumeister, H. (2015). Increasing the ac-

ceptance of internet-based mental health interventions

in primary care patients with depressive symptoms. a

randomized controlled trial. Journal of affective dis-

orders, 176:9–17.

Fishbein, M. (1979). A theory of reasoned action: some ap-

plications and implications. In Nebraska Symposium

on Motivation. University of Nebraska Press.

Fougeyrollas, P. and Noreau, L. (2001). Life Habits.

Heart, T. and Kalderon, E. (2013). Older adults: Are they

ready to adopt health-related ICT? International Jour-

nal of Medical Informatics, 82(11):e209–e231.

IBM (2017). Ibm spss statistics.

iHealth Labs Inc. (2019). ihealth. (Accessed on

01/03/2020).

Innovations, B. (2016). BeWell Innovations.

Jaschinski, C. (2014). Ambient Assisted Living: Towards

a Model of Technology Adoption and Use Among El-

derly Users. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM Interna-

tional Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous

Computing: Adjunct Publication, UbiComp ’14 Ad-

junct, pages 319–324, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Jaschinski, C. and Allouch, S. B. (2015). Understanding the

user’s acceptance of a sensor-based ambient assisted

living application. In Human Behavior Understand-

ing, pages 13–25. Springer.

Jim

´

enez-Mixco, V., Cabrera-Umpi

´

errez, M. F., Arren-

dondo, M. T., Panou, M., Struck, M., and Bonfiglio,

S. (2013). Feasibility of a wireless health monitoring

system for prevention and health assessment of elderly

people. In 2013 35th Annual International Conference

of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology So-

ciety (EMBC), pages 7306–7309, Osaka, Japan. IEEE.

Khechine, H., Lakhal, S., and Ndjambou, P. (2016).

A meta-analysis of the utaut model: Eleven

years later. Canadian Journal of Administra-

tive Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de

l’Administration, 33(2):138–152.

Kononova, A., Li, L., Kamp, K., Bowen, M., Rikard, R.,

Cotten, S., and Peng, W. (2019). The use of wear-

able activity trackers among older adults: Focus group

study of tracker perceptions, motivators, and barriers

in the maintenance stage of behavior change. JMIR

mHealth and uHealth, 7(4):e9832.

Lemmens, J., Ism van Engelen, E., Post, M. W., de Witte,

L. P., Beurskens, A., Wolters, P. M., and de Witte, L. P.

(2007). Reproducibility and validity of the dutch life

habits questionnaire (life-h 3.0) in older adults. Clini-

cal rehabilitation, 21(9):853–862.

Lumos Labs, I. (2020). Lumosity brain training. (Accessed

on 01/03/2020).

McMahon, S. K., Lewis, B., Oakes, M., Guan, W., Wyman,

J. F., and Rothman, A. J. (2016). Older adults’ ex-

periences using a commercially available monitor to

self-track their physical activity. JMIR mHealth and

uHealth, 4(2):e35.

Nations, U. (2015). World Population Prospects - Popula-

tion Division - United Nations.

Nunes, F., Verdezoto, N., Fitzpatrick, G., Kyng, M.,

Gr

¨

onvall, E., and Storni, C. (2015). Self-care tech-

nologies in hci: Trends, tensions, and opportunities.

ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction

(TOCHI), 22(6):1–45.

The Unacceptance of a Self-Management Health System by Healthy Older Adults

279

Peek, S., Luijkx, K., Vrijhoef, H., Nieboer, M., Aarts, S.,

Van Der Voort, C., Rijnaard, M., and Wouters, E.

(2017). Origins and consequences of technology ac-

quirement by independent-living seniors: towards an

integrative model. BMC geriatrics, 17(1):189.

Peek, S. T., Luijkx, K., Vrijhoef, H., Nieboer, M., Aarts,

S., van der Voort, C., Rijnaard, M., and Wouters, E.

(2019). Understanding changes and stability in the

long-term use of technologies by seniors who are ag-

ing in place: a dynamical framework. BMC geriatrics,

19(1):1–13.

Peek, S. T., Luijkx, K. G., Rijnaard, M. D., Nieboer, M. E.,

van der Voort, C. S., Aarts, S., van Hoof, J., Vrijhoef,

H. J., and Wouters, E. J. (2016). Older adults’ reasons

for using technology while aging in place. Gerontol-

ogy, 62(2):226–237.

Queir

´

os, A., Cerqueira, M., Santos, M., and Rocha, N. P.

(2017). Mobile health to support ageing in place:

A synoptic overview. Procedia computer science,

121:206–211.

Sintonen, S. and Immonen, M. (2013). Telecare services

for aging people: Assessment of critical factors influ-

encing the adoption intention. Computers in Human

Behavior, 29(4):1307–1317.

Taiwo, A. A. and Downe, A. G. (2013). The theory of user

acceptance and use of technology (utaut): A meta-

analytic review of empirical findings. Journal of The-

oretical & Applied Information Technology, 49(1).

Van der Zee, K. and Sanderman, R. (1993). Rand-36.

Groningen: Northern Centre for Health Care Re-

search, University of Groningen, the Netherlands,

28:6.

Vanneste, D., Vermeulen, B., and Declercq, A. (2013).

Healthcare professionals’ acceptance of BelRAI, a

web-based system enabling person-centred recording

and data sharing across care settings with interRAI in-

struments: a UTAUT analysis. BMC Medical Infor-

matics and Decision Making, 13(1).

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., and Davis, F. D.

(2003). User Acceptance of Information Technology:

Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly, 27(3):425–

478.

Verdezoto, N. and Gr

¨

onvall, E. (2016). On preventive blood

pressure self-monitoring at home. Cognition, Technol-

ogy & Work, 18(2):267–285.

Vines, J., Pritchard, G., Wright, P., Olivier, P., and Brit-

tain, K. (2015). An Age-Old Problem: Examining the

Discourses of Ageing in HCI and Strategies for Fu-

ture Research. ACM Trans. Comput.-Hum. Interact.,

22(1):2:1–2:27.

Walters, S. J., Munro, J. F., and Brazier, J. E. (2001).

Using the sf-36 with older adults: a cross-sectional

community-based survey. Age and ageing, 30(4):337–

343.

Wang, J., Du, Y., Coleman, D., Peck, M., Myneni, S.,

Kang, H., and Gong, Y. (2019). Mobile and con-

nected health technology needs for older adults aging

in place: Cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Aging,

2(1):e13864.

Ware, J. E. and Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). RAND-36 item

Health Survey.

Young, R., Willis, E., Cameron, G., and Geana, M. (2013).

“Willing but Unwilling”: Attitudinal barriers to adop-

tion of home-based health information technology

among older adults:. Health Informatics Journal.

TEG 2020 - Special Session on Technology, Elderly Games

280