Teaching Research Methods for Computer Science Students using

Virtual Learning: A Case Study

Sarah Alhumoud

1

, Areeb Alowisheq

1

and Nora Altwairesh

2

1

Computer Science Department, Al Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, (IMSIU), Saudi Arabia

2

Information Technology Department, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia

Keywords: Virtual Learning Environment (VLE), Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs).

Abstract: Research skills are crucial for education, and overall scientific prosperity. In Saudi Arabia, a gap exists in the

research skills and knowledge necessary for higher education students. This paper highlights the current state

of university curricula in terms of teaching scientific research skills and methods in Saudi Arabia. Also, it

presents a low-cost learning model, called ASA research camp, that was applied to bridge the knowledge gap.

This exhibits a virtual class that combine qualities of both VLEs and MOOCs. The course spanned three

months in two phases: theoretical for listening and discussion, and practical for guided paper writing. Surveys

show that the 200 participants had maximum learning value with minimal cost. Moreover, on finishing the

course, the members of the practical part, 16 students, were able to publish three papers in Springer Lecture

Notes in its Computer Science book series as a result of the guided paper writing phase.

1 INTRODUCTION

The trend towards online learning starting from

virtual learning environments (VLEs) and advancing

to massive open online courses (MOOCs) has

recently expanded greatly. VLEs are systems such as

Blackboard and Moodle used in the context of

universities and other Higher Education Institutions.

They are usually included with courses whose

instructors are able to give feedback and directly

mark up the papers of a limited number of students.

In contrast, MOOCs are open educational systems

that can be offered from universities but are

independent and vast in terms of the student base.

Examples of MOOCs are edX, Coursera, Udemy, and

Udacity. Worldwide, MOOC courses are offered to

thousands and hundreds of thousands of students.

This raises the possibility of offering higher education

to a wider base of students with minimum to no fees

bridging the gap between privileged and

disadvantaged learners (Kay et al., 2013; Zheng et al.,

2015). MOOCs give students a great chance to learn

from leaders and elite scientists directly. However,

there are some issues related to it, such as a high

dropout rate (Panagiotis Adamopoulos, n.d.; Zheng et

al., 2015), or what Clow calls (Clow, 2013) the

‘funnel of participation’, starting with thousands of

students and ending the course with only a few,

resulting in a 5% passing rate in some cases (Kay et

al., 2013).

Several studies were conducted to measure the

effectiveness of virtual classes as opposed to

traditional face-to-face classes. A marked study was

done in King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia

(Al-Nuaim, 2012). The study shows that courses done

by the Deanship of Distance Learning proved

successful in terms of providing a comparable

educational experience as opposed to traditional

courses. Another study carried out on 122 students in

a Greek university shows that the limited mobile

access could affect using Moodle as an active

learning tool rather than a document repository

(Papadakis et al., 2017). This issue is not widely

problematic in Saudi Arabia as the internet pentation

rate is 93% (Simon Kemp, n.d.) and the mobile

penetration is 126% (CITC, n.d.) as of 2020 and 2019

respectively. This is a success factor to the learning

model we propose. In our learning model, we mix the

VLE and MOOC styles. That is, we open the course

to the public, but at the same time, we provide a

chance for direct contact with instructors. In this case

study, we will review the process and results of our

virtual class (ASA Research Camp). The camp

teaches and gives practice in scientific research

518

Alhumoud, S., Alowisheq, A. and Altwairesh, N.

Teaching Research Methods for Computer Science Students using Virtual Learning: A Case Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0009804205180522

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 1, pages 518-522

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

methods and skills for computer science college

students.

This was motivated by the minimal exposure that

students receive to scientific research methods and

techniques in many universities in Saudi Arabia. This

is evident from a review we conducted on the

programs of 10 computing colleges in the largest

Saudi universities in terms of enrolled students. These

10 computing colleges had a total of 35 computer

majors. Each major contained an average of 40

courses in their programs. There were no courses

dedicated to research methods and skills in 30 out of

the 35 majors, and in the 5 remaining ones there was

at most one course as shown in Table 1. The

following universities are under consideration: King

Faisal University (KFU), King Abdulaziz University

(KAU), Al Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic

University (IMSIU), Umm Al Qura University

(UQU), Qassim Univesity (QU), Taif University

(TU), Taibah University (TaibahU), King Khalid

University (KKU), Jazan University (JazanU), King

Saud University (KSU). In addition to the scarcity of

courses focusing on scientific research, students

rarely have opportunities to be mentored by

experienced researchers, despite the importance of

such opportunities in developing their research skills

(Gonzalez, Cristina, n.d.). On this basis, the goals of

the research camp are as follows:

1) promoting awareness of scientific research

practices between college students; 2) sharing

experiences between attendees and instructors; 3)

providing an easily accessible learning experience

from the premises and comfort of homes in the field

of scientific research; 4) teaching scientific paper

writing through direct mentoring and experiential

learning. 5) providing a complete compressed course

on scientific research concepts starting from idea

selection, to paper writing, and ending with the

paper’s publication and presentation.

This paper sheds light on the research camp

approach, organization and operation. The challenges

experienced by the camp leaders are discussed.

Finally, the reflections and conclusions are

mentioned.

2 RESEARCH CAMP APPROACH

Through the implementation of the ASA research

camp, we sought to answer the following research

questions:

1) Would the camp successfully support learning the

main scientific research concepts in a virtual

learning environment?

Table 1: Number of Scientific Research Courses in the

largest 10 Universities in Saudi Arabia.

University

#

students

#

Computer

Majors

#Research

courses in all

Majors

KFU 161,204 4 0

KAU 156,505 3 0

IMSIU 107,609 4 1

UQU 102,237 4 1

QU 67,822 3 0

TU 61,138 3 0

TaibahU 57,744 3 0

KKU 56,466 4 2

JazanU 54,306 3 0

KSU 49,501 4 1

TOTAL 35 5

Table 2: Research Camp Timetable.

Time Date Phase Levels

6:00-9:00

PM

1 Oct

Theory

Level 1: Introduction to

scientific paper writing

9:00 PM 7 Oct

Proposal submission

6:00-9:00

PM

8 Oct

Level 2: Presentation

techniques

6:00-9:00

PM

15 Oct

Practice

Level 3: Present accepted

proposals

- 22 Oct -

30 Nov

Level 4: Guided paper

writing

- 30 Nov

Submit paper for review

Table 3: Registration form questions.

Questions

1. Arabic

Full name

6.

University

11. Did you read

scientific papers before?

2. English

Full name

7. Country

12. Did you write a

scientific paper before?

3. Email 8. Level 13. Why join?

4. Mobile 9. Major 14. Your expectation

5. GPA

10. English

Proficiency

15. I’m able to attend

online on the specified

dates and the information

I provided here is correct.

2) Would the students be able to reach the goal of

writing a research paper? In the following section,

the camp organization and operation are

explained.

Teaching Research Methods for Computer Science Students using Virtual Learning: A Case Study

519

2.1 Research Camp Organization

ASA stands for Arabic sentiment analysis and it is the

name of the research group that held the camp, with

the primary investigator being the camp leader and

the first author of this paper. The research camp was

organized into two administrative phases and four

educational levels, Table 2. The administrative

phases include advertisement and registration. The

advertisement was done through a tweet from the

ASA research group’s Twitter account with more

than 1,000 followers and through WhatsApp

messaging. By the fourth day of announcing the

camp, more than 200 applicants had applied. The

registration form questions are listed in Table 3. The

registered applicants were divided into two groups,

campers and listeners. Campers attended and

participated in all levels, whereas listeners attended

the first two levels. Upon analysing the registration

form, campers were selected according to several

criteria related to their answers to questions 10-15.

After finishing the camp levels and upon successful

paper compilation, the campers submitted the paper

for review and publication.

2.2 Research Camp Operation

The camp started with 200 virtual participants

between listeners and campers. The participants were

given a three-hour crash course on scientific research

methods, including idea selection and scrutiny, and

paper structure and writing. The course was

facilitated by WebEx, a web conferencing tool. This

tool offers different functions for students like rise

hand for voice participation and asking questions,

applause, and text chat for communicating issues like

questions or comments. Those functions aid in the

students’ interaction and learning process. A more

complex set of function and tools is offered to the

course instructor those include application sharing,

polls, break-out sessions for breaking students into

smaller groups, and session recording and ending. In

order to move to the next level, campers where asked

to submit a research proposal or select one from the

ideas presented to them and lead by the mentors, and

in both cases, write a brief proposal around it. On

level 2, essential presentation skills are described to

help scientists and researchers who have excellent

work but lack the ability to promote their projects. At

the close of that session, listeners were thanked for

attending, and given a feedback form to fill. Also,

subgroups of participants, campers, were pulled out

into separate virtual classrooms for a tentative

proposal discussion and formation, each group with a

senior researcher mentor. The work on the proposal

continued asynchronously until the time of level 3,

when each group had the chance to present its

proposal. Next, each group had a separate meeting to

setup the communication policy for the next two

months. Meetings to write the paper were continued

until the paper of each group was submitted to the

publication venue.

3 RESEARCH CAMP ANALYSIS

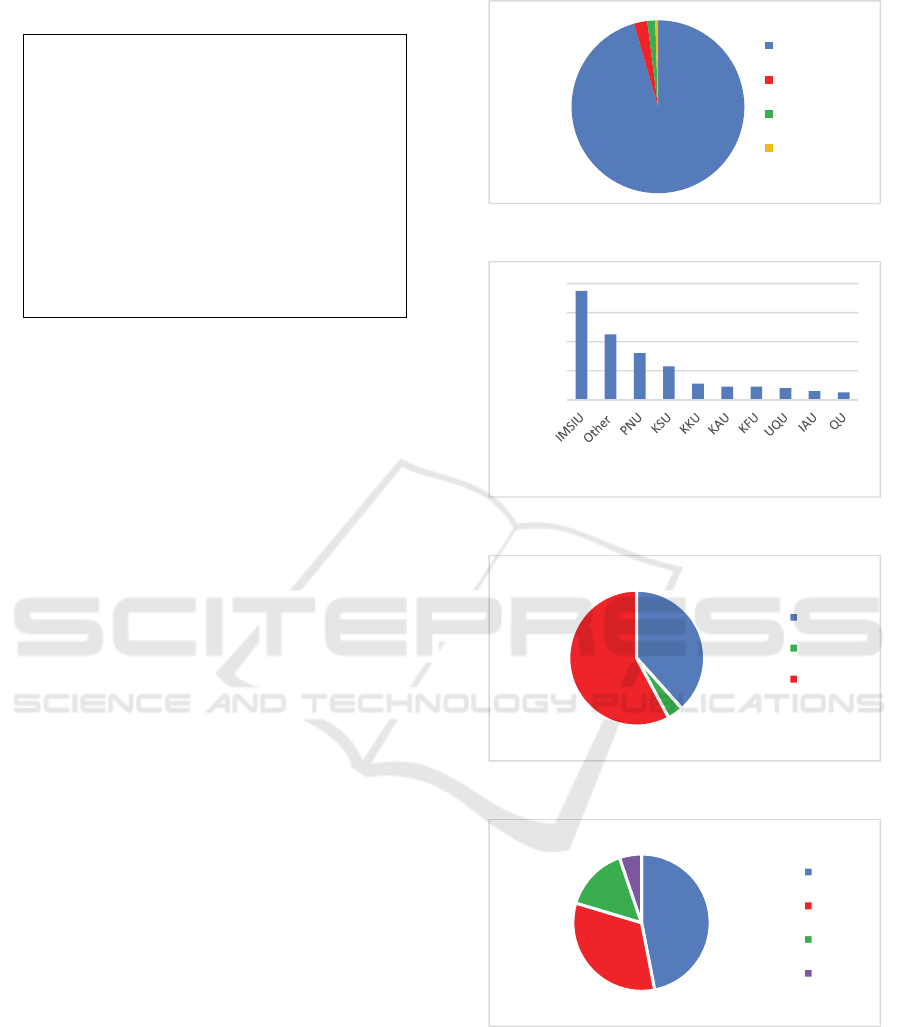

The camp applicants were coming from four different

countries, and from more than 10 universities. The

majority are from Saudi Arabia, as shown in Figure

1. Also, applicants were graduates or studying in one

of the universities shown in Figure 2 with the majority

being from IMSIU. This was expected as the research

group offering the camp is based in IMSIU. The

applicants’ educational backgrounds varied, with the

majority (58%) still studying for their bachelor’s or

having earned it, while 42% were postgraduate

students, Figure 3. The academic majors of applicants

were mainly computer science (CS), at 47%. This was

probable as the reach of advertisement was

propagated dominantly by the research group

members, who are mostly majoring in CS. Coming

next was information systems (IS) at 33%, followed

by 15% of the participants majoring in information

technology (IT).

Ninety nine percent of the participants were

female. This was understandable as the camp was

organised and held by faculty from the female

section, as all universities in Saudi Arabia are split

into two mostly identical sections, males and females.

Also, this could be explained by the ease of

attendance for female participants: at the time the

camp was held, woman were not allowed to drive in

Saudi Arabia, thus the online camp provided a rare

chance to learn from home with no need to arrange

suitable transportation to participate and attend. On

analysing the feedback forms, the feedback we

received was 90% highly positive on the first

two

levels that were presented to both listeners and

campers, Table 4.

The levels were satisfactory to most of the

participants. This could be explained as listeners and

campers were offered rich information in an open

discussion manner.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

520

Table 4: Part of the feedback messages.

- thank you, I rarely find someone to guide and

mentor me closely.

- Great start! I've learned more than what I

expected. Thank you so much.

- I learned many things such as how to motivate

myself, steps to write a paper, how to know the

best journals.

- I learned the basics of academic writing,

publishing venues and evaluating them, how to

go about exploring a research problem.

- all the course content is excellent and important.

- this course gave a push to endure research

problems and made me realise that I’m not alone

in that.

Presenting them a rare chance to ask and interact

with experienced researchers with no cost at all. Even

the cost of attending a real class in terms of

transportation and time was deducted. Delivering the

course in a virtual learning environment provides a

chance for both synchronous and asynchronous

communication. This potentially provides deeper and

varied forms of dialogue and interaction between

students and mentors and among peers. This fulfils

socially situated learning, one of the seven eLearning

applied theories described by (Conole et al., 2004).

In the practical part of the course, the campers had

the chance to experience and reflect on scientific

research fundamentals while being mentored to write

a whole paper, fulfilling experiential learning (Conole

et al., 2004). On finishing the camp, the campers had

worked in three groups and written three different

papers with the guidance of a senior researcher in

each group. The papers resulting from those groups

were all published in Springer Lecture Notes in its

Computer Science book series (Almuqren et al.,

2017; AlNegheimish et al., 2017; Alowisheq et al.,

2017)

.

4 RESEARCH CAMP

CHALLENGES

Employing a virtual methodology for teaching the

introduction to scientific research and providing the

means for potential authors to experience writing a

paper with guided mentorship and peer collaboration

had positive outcomes. This however, faced several

challenges, which are as follows: First, given that the

campers group was composed of virtual teams whose

members have not met in person and are from varying

backgrounds having to work on a rigorous scientific

writing project that needed synchronisation and high

coordination, this required a huge leadership effort

Figure 1: Participants' countries.

Figure 2: Participants' affiliations.

Figure 3: Current level of education.

Figure 4: Academic Majors of participants.

for it to succeed. Second, the success of online

meetings depends on the quality of the Internet

connection of the attendees.

Third, although the screening of campers who

joined the paper writing groups went through

different filtering and scrutiny phases, there were still

some essential qualities that could not be discovered

SaudiArabia

Oman

UnitedKingdom

UnitedStates

96%

0

20

40

60

80

Numberofapplicants

Universitiesstudyinginorgraduatedfrom

38%

4%

58%

Master

PhD

Other

47%

33%

15%

5%

CS

IS

IT

Other

Teaching Research Methods for Computer Science Students using Virtual Learning: A Case Study

521

solely by the registration forms. This includes,

English language competency, scientific background,

motivation, and commitment. As a result, some group

members were not active in reaching the goal as other

members. Thus, having some rigorous English

proficiency measures such as IELTS or TOEFL will

aid in setting the expectations early before the writing

levels.

Fourth, keeping the campers learning and

motivated to finish writing the paper with high

commitment in attending the meetings and doing the

writing assignments required a strong effort in

follow-up and coaching, while that happened, we still

lost 3 group members from reaching the final goal.

This is attributed to either inability to continue.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The ASA research camp provided a learning

experience exercising several pedagogical and

educational traits that are required for good learning

such as socially situated learning and experiential

learning. In this course WebEx was used for teaching

scientific research methods to computer science

students. Although the mentors and participants faced

different challenges, they were able to elicit three

academically sound papers in a learning journey that

positively affected campers. The listeners on the first

two levels were also positively affected and learned

with minimal cost. This fulfils the two research

questions we asked on proposing the research camp.

However, to minimise challenges and aid future

success, we suggest having more mentors per

campers’ group with at least two mentors per group.

Also, for guided paper writing starting in level 3, a

group of two mentors and five students at maximum

is suggested. Lastly, as the survey show, only 5

courses among 35 majors in 10 different colleges in

Saudi Arabia are on scientific research. Also, 6 out of

10 colleges do not offer any course on scientific

research. This is a huge gap in teaching scientific

research methods in computer science colleges in

Saudi Arabia that needs to be improved.

REFERENCES

Almuqren, L., Alzammam, A., Alotaibi, S., Cristea, A., &

Alhumoud, S. (2017). A Review on Corpus Annotation

for Arabic Sentiment Analysis. In G. Meiselwitz (Ed.),

Social Computing and Social Media. Applications and

Analytics (pp. 215–225). Springer International

Publishing.

AlNegheimish, H., Alshobaili, J., AlMansour, N., Shiha, R.

B., AlTwairesh, N., & Alhumoud, S. (2017). AraSenTi-

Lexicon: A Different Approach. In G. Meiselwitz (Ed.),

Social Computing and Social Media. Applications and

Analytics (pp. 226–235). Springer International

Publishing.

Al-Nuaim, H. A. (2012). The Use of Virtual Classrooms in

E-learning: A Case Study in King Abdulaziz

University, Saudi Arabia. E-Learning and Digital

Media, 9(2), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.2304/elea.

2012.9.2.211

Alowisheq, A., Alrajebah, N., Alrumikhani, A., Al-

Shamrani, G., Shaabi, M., Al-Nufaisi, M., Alnasser, A.,

& Alhumoud, S. (2017). Investigating the Relationship

Between Trust and Sentiment Agreement in Arab

Twitter Users. In G. Meiselwitz (Ed.), Social

Computing and Social Media. Applications and

Analytics (pp. 236–245). Springer International

Publishing.

CITC. (n.d.). ICT Performance Indicators. Communica-

tions and Information Technology Commissio.

https://www.citc.gov.sa/en/indicators/Indicators%20of

%20Communications%20and%20Information%20Tec

hn/ICT%20Indicators%20in%20the%20Kingdom%20

of%20Saudi%20Arabia%20(Q1%202019).pdf

Clow, D. (2013). MOOCs and the Funnel of Participation.

Proceedings of the Third International Conference on

Learning Analytics and Knowledge, 185–189.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2460296.2460332

Conole, G., Dyke, M., Oliver, M., & Seale, J. (2004).

Mapping pedagogy and tools for effective learning

design. Computer Education, 43, 17–33.

Gonzalez, Cristina. (n.d.). Undergraduate research,

graduate mentoring, and the university’s mission.

Science, 293(5535), 1624–1626.

Kay, J., Reimann, P., Diebold, E., & Kummerfeld, B.

(2013). MOOCs: So Many Learners, So Much

Potential ... IEEE Intelligent Systems, 28(3), 70–77.

https://doi.org/10.1109/MIS.2013.66

Panagiotis Adamopoulos. (n.d.). What Makes a Great

MOOC? An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Student

Retention in Online Courses. Proceedings of the 34th

International Conference on Information Systems, ICIS

’13.

Papadakis, S., Kalogiannakis, M., Sifaki, E., & Vidakis, N.

(2017). Access Moodle Using Smart Mobile Phones. A

case study in a Greek University.

Simon Kemp. (n.d.). DIGITAL 2020: SAUDI ARABIA.

https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-saudi-

arabia

Zheng, S., Rosson, M. B., Shih, P. C., & Carroll, J. M.

(2015). Understanding Student Motivation, Behaviors

and Perceptions in MOOCs. Proceedings of the

18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported

Cooperative Work; Social Computing, 1882–1895.

https://doi.org/10.1145/2675133.2675217

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

522