Software Ecosystems and Digital Games: Understanding the Financial

Sustainability Aspect

Bruno Lopes Xavier

1

, Rodrigo Pereira dos Santos

1

and Davi Viana dos Santos

2

1

Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

2

Universidade Federal do Maranh

˜

ao (UFMA), S

˜

ao Lu

´

ıs, Brazil

Keywords:

Software Ecosystem, Digital Games, Grounded Theory, Sustainability, Software Engineering.

Abstract:

The digital games industry has a deep alignment with the field of Software Ecosystems (SECO). Despite the

strict relationship, actors of the games industry do not apply the SECO perspective to understand the dynamics

of the environment. Financial sustainability is considered a key factor for the permanence of these actors on the

platforms and directly impacts the sustainability of an ecosystem. This paper presents a qualitative analysis

in that challenging aspect of the digital game industry based on SECO concepts. A survey research that

identified the benefits, problems and challenges aspects reported by games actors of digital games SECO in

Brazil bases the statements and the analysis of this study. The focus was on exploring the reports of financial

sustainability through the SECO perspective in order to help actors to understand the technical, business and

social elements of this global and interconnected industry in the area of Information Systems. Finally, some

ideas for academic research are listed, such as the need to use knowledge management to support studies on

the business dimension of digital games SECO and the need to explore further relationships among games

industry actors in the Brazilian context.

1 INTRODUCTION

The approach of using a common technological plat-

form that integrates several software products has re-

placed the development of a unique software prod-

uct (Santos and Werner, 2012). Big companies such

as Apple, Google, Amazon, and Microsoft are prac-

tical examples of this change in the software market

(Santos et al., 2012; Manikas, 2016). Such approach

is related to a research area in Software Engineering

known as Software Ecosystems (SECO).

With the advent of several SECO in the market,

the software industry changed its operation, affecting

the games industry. The leading digital games plat-

forms (e.g. GooglePlay, AppleStore, Nintendo Wii,

Xbox Live, PlayStation Network, Steam) can be char-

acterized as SECO, demonstrating the dominance of

this strategy in the current scenario. The growth of

the digital games industry in Brazil in recent years

(Fleury et al., 2014; Sakuda and Fortim, 2018) and

the challenges that such industry faces over the years

(Nahar et al., 2012; Fleury et al., 2014; Sakuda and

Fortim, 2018; Martins et al., 2018; M

¨

antym

¨

aki et al.,

2019) leverages the need to explore the dynamics and

relationships of the players immersed in this new mar-

ket scenario.

The SECO strategy has enabled the exponential

growth of the networks of actors that make up the

software industry. The saturation of new products,

among them digital games, has brought a high de-

gree of competition among actors. As a result of this

dispute in the digital games market, we observe the

emergence of a critical challenge regarding the finan-

cial sustainability (Kasurinen et al., 2017; Sakuda and

Fortim, 2018; Sormunen et al., 2019).

The sustainability of a SECO is directly linked

to the constant collaboration among actors over time,

aiming to promote the ecosystem (Dhungana et al.,

2010). The frequent participation of external ac-

tors considered a crucial feature in SECO (Bosch,

2009; Santos and Werner, 2012) depends on the

advantages and benefits they achieve by collaborat-

ing/contributing to the ecosystem. In order to support

an understanding of this relationship, it is necessary

to analyze a SECO in dimensions (Santos and Werner,

2012; Barbosa et al., 2013), being the business dimen-

sion responsible for dealing with economic aspects

between the common technology platform and its ac-

tors.

The growth of networks of actors on technologi-

450

Lopes Xavier, B., Pereira dos Santos, R. and Viana dos Santos, D.

Software Ecosystems and Digital Games: Understanding the Financial Sustainability Aspect.

DOI: 10.5220/0009794204500457

In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2020) - Volume 2, pages 450-457

ISBN: 978-989-758-423-7

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

cal platforms over the past few years has made SECO

emerge as a research area in academia (Bosch, 2009;

Manikas and Hansen, 2013; Berg, 2015; Manikas,

2016). Among the different studies of SECO, some

highlight the need for mapping the network of actors

as one of the challenges for the field (Jansen et al.,

2009; Santos et al., 2012; Serebrenik and Mens, 2015;

Alves et al., 2017; Santos, 2017).

In this context, the main objective of this work

is to use the theoretical lens of SECO to explore the

challenge of financial sustainability of players in the

digital games industry in Brazil. We conducted a sur-

vey research covering all macro-regions of the coun-

try. This survey sought to identify benefits, problems,

and challenges of actors participating in SECO that

encompass digital games operating in Brazil. We ap-

plied Grounded Theory (GT) to support our analysis.

This paper focused on the aspects related to the chal-

lenge of financial sustainability identified in this sur-

vey research.

This work is organized as follows: Section 2 ad-

dresses the theoretical background. Section 3 presents

the methodology methodology to conduct survey re-

search as well as the analysis procedures. Sections

4 and 5 present the results of the survey. Section 6

brings the discussion based on the results. Section 7

complements the discussion by highlighting the lim-

iting points of this study. Finally, Section 8 presents

the final considerations, listing some opportunities of

future work.

2 SOFTWARE ECOSYSTEM AND

DIGITAL GAMES

A game is an ancient element in humanity. There

are records of games developed around 3,000 B.C.

(Finkel, 2007). Another example is the oldest chess

game in the world, which dates from 700 B.C. (Ba-

naschak, 1999).

New modalities and game forms have emerged

and are influenced by technological advances

throughout human history. The era of digital games

began with the launch of the first computer game

in 1952 and the first video game console in 1958.

The creation of the electronic entertainment by 1980s

consolidated the digital games (Neto et al., 2009).

Some studies highlight the relationship between digi-

tal games and the software industry (Engstr

¨

om, 2019;

McKenzie et al., 2019; Toftedahl and Engstr

¨

om,

2019).

In this context, the “SECO” can be better un-

derstood when addressing the meaning of the word

“ecosystem” in isolation, which comes from biol-

ogy. The word “ecosystem” is used in different con-

texts to understand the evolutionary nature of pro-

cesses, activities, and relationships (Dhungana et al.,

2010; Garc

´

ıa-Holgado and Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo, 2018).

By adding the word “software” a focus is given to the

software components that form more complex sys-

tems (Garc

´

ıa-Holgado and Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo, 2018).

SECO is the interaction of software and actors

through a common technological platform, which re-

sults in a set of direct or indirect contributions and

influences to the community (Manikas, 2016). It is

important to emphasize that this term have several

definitions in the academic literature (Manikas and

Hansen, 2013; Garc

´

ıa-Holgado and Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo,

2018).

There are also several ways to analyze a SECO,

and this study uses the definitions addressed in (San-

tos and Werner, 2012; Barbosa et al., 2013). The

dimensions of SECO help in the understanding of

dynamics and relationships are a perspective aligned

with the objective of this research.

• Technical - addresses topics such as the life cy-

cle, features, and architecture of the centralizing

platform;

• Business - related to the flow of knowledge,

resources and information through the business

view; and

• Social - explore how the network of actors evolves

to achieve its objectives.

Another relevant term in SECO literature for this

study is “sustainability”. Sustainability in SECO

is the ecosystem’s ability to increase or maintain

its user/developer community over time, ensuring

its survival against inherent changes regarding new

technologies, products, competitors, users and at-

tacks/sabotages (Dhungana et al., 2010).

According to Barbosa et al. (2013), sustain-

ability is considered a fundamental aspect of the

business dimension and a critical element in SECO.

As such, SECO must be attentive to the mainte-

nance/enhancement of its user/developer community

for long periods, and the financial sustainability of the

actors is a crucial factor for SECO platforms.

3 SURVEY

The methodological approach adopted was an online

survey research using a questionnaire technique with

open and closed questions. The survey research is a

comprehensive survey method that aims to describe,

compare and explain knowledge, attitudes, and be-

haviors through data collection. In turn, a question-

Software Ecosystems and Digital Games: Understanding the Financial Sustainability Aspect

451

naire is an instrument that groups questions in a writ-

ten format to facilitate the administration of data col-

lection (Shull et al., 2007).

For data analysis, this study uses the Grounded

Theory (GT) procedures. Although GT proposes the

construction of theories, Corbin and Strauss (2014)

state that it can be applied to achieve specific research

objectives, such as the understanding of phenomena

or scenarios.

3.1 Planning

The survey research aimed to characterize the Brazil-

ian scenario of digital games industry. To do so, ques-

tions about benefits, problems, and challenges for par-

ticipating in digital games SECO from actors working

in industry and academia were prepared. It is impor-

tant to notice that the objective of this paper was to

presented an specific part of our research related to the

challenge of financial sustainability from the opinion

poll.

The planning starts with the definition of the sur-

vey questionnaire. The characterization questions in-

volve the academic level, the job profile (academy,

industry or both), the expertise area (administrative

or technical), and the institution information (name,

website and social network). The last three questions

are open questions that asked about the challenges,

problems and benefits faced by the respondents.

3.2 Execution

The survey was made available via GoogleForm

1

from October 17, 2018 to February 1, 2019. The

survey reached 287 participants, 200 of whom were

within the survey target profile. The valid participants

work in institutions from all regions of Brazil.

3.3 Analysis Procedure

To start the analysis of the open questions, the codi-

fication phases in the GT (Corbin and Strauss, 2014)

were observed: (1) open, (2) axial and (3) selective.

In the open coding, a detailed reading of the answers

suports the codes that represent terms/expressions. In

the axial coding, the relationships/hierarchizations of

the codes emerged. In selective coding, the central

idea of the study arises, that is, the category to which

the others are related.

The GT’s coding process is finalized when the the-

oretical saturation is reached and the insertion of new

data does not produce new knowledge, revisions or

1

Tool that allows to collect user information through a

survey.

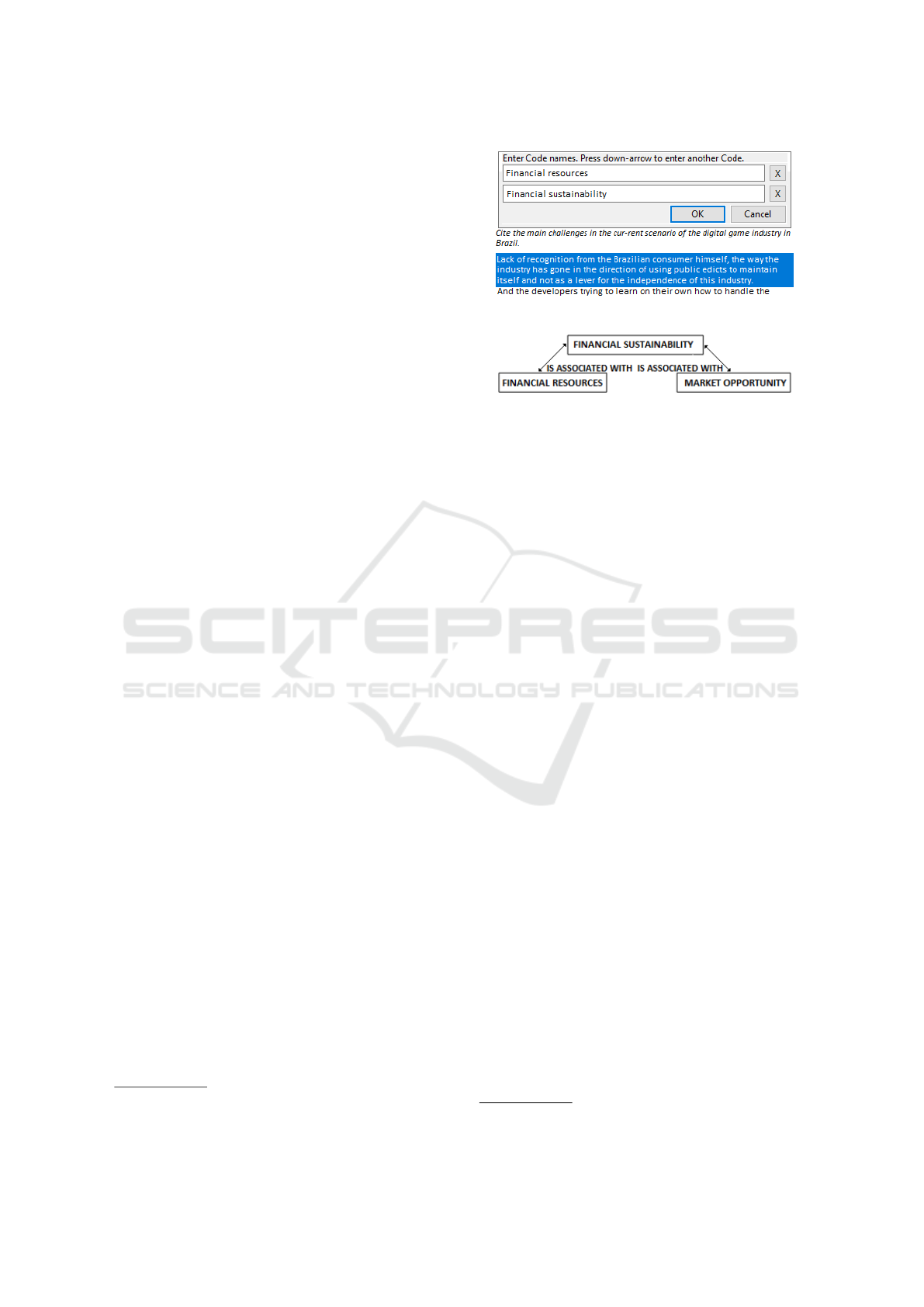

Figure 1: Opened Coding Stage in Atlas.TI.

Figure 2: Axial Coding Stage in Atlas.TI.

reinterpretations (Stol et al., 2016). To assist the cod-

ing process, the software Atlas.TI

2

was used. In the

open coding, the answers were analyzed in detail as

illustrated in Figure 1, aiming to create codes related

to specific fragments or direct quotations.

In this study, direct quotes finish with the respec-

tive participant identification, named by the letter “P”

followed by his/her identification number. The num-

ber follows the total number of survey participants

(maximum number of 287) to maintain the integrity

of the data in the use of Atlas.TI.

After defining the codes, axial coding starts as il-

lustrated in Figure 2, identifying the categories and

relationships between codes. In Atlas.TI, the relations

between codes are represented by a solid black arrow.

4 QUANTITATIVE RESULTS

Among the 200 valid participants in the opinion poll,

135 (67.50%) mentioned at least one of the challenges

highlighted in this study. From 135 participants, 62

(45.92%) identified themselves as members of the

academy (A), 51 (37.77%) as members of industry

(I), and 22 (16.29%) as members of academia and in-

dustry simultaneously (A&I), according to Table 3.

In total, 6 codes related to financial sustainability

were identified in the challenge group. Table 1 pro-

vides a brief description of the codes based on the

participants’ reports. Table 2 counts the total num-

ber of citations per participant profile regarding the

Academy (A), Industry (I) and Academy and Industry

(A&I). A participant might have concentrated quota-

tions for more than one code.

2

https://atlasti.com/

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

452

Table 1: Description of codes.

Code Title Description

C1 Financial

Sustainability

Balance and financial

support of the actors.

C2 Bureaucracy Rules and procedures

related to the activities

of the sector.

C3 Production

Cost

Resource values for

production.

C4 Financial Re-

sources

Raising of monetary

resources.

C5 Tax Burden Cash collection on the

activities of the sector.

C6 Market

Opportunity

Market/business con-

ditions.

C7 Attract Audi-

ence

Engagement and at-

traction of users.

Table 2: Code citations.

Code A I A&I Total %

C1 4 15 5 24 12,37

C2 1 3 3 7 3,61

C3 9 6 1 16 8,25

C4 38 26 14 78 40,20

C5 5 11 2 18 9,28

C6 10 9 2 21 10,82

C7 14 10 6 30 15,47

Total 81 80 33 194 100

Table 3: Participants profiles.

Role Quantity %

Academy 62 45,92

Industry 51 37,78

Academy and Industry 22 16,30

Total 135 100

5 QUALITATIVE RESULTS

The following subsections discuss the details of the

definitions and relationships that permeate the chal-

lenge of financial sustainability of the digital games

SECO’s actors. Two researchers were responsible for

drafting codes and relationships.

5.1 Financial Sustainability

This code represents the central point of the study.

Financial sustainability addresses monetary order as-

pects concerning the integral performance and long-

term permanence of players in the digital games

SECO. To achieve this challenge, it is necessary to

understand the codes related to it.

5.2 Bureaucracy

Bureaucracy addresses processes and regulations that

hinder the operation and, consequently, the growth of

sustainability of the SECO actors. This code perme-

ates the maintenance of companies, processes in gov-

ernment entities, and access to financial resources for

investment or billing. This code also involves aca-

demic activities.

5.3 Production Cost

This code was identified in fragments that describe fi-

nancial challenges for the execution of the actors’ ac-

tivities. The acquisition of equipment, software, team

building and maintenance of product quality form this

challenge.

As a cause for the high cost of production, some

participants point the tax burden for importation and

the need for specialized and experienced labor. In

turn, diversification of the public beyond entertain-

ment and the use of specific platforms emerged as al-

ternatives for the cost in the production process.

This code contributes to the lack of sustainability

of the sector, as the initial input needed for produc-

tion is considered high by national standards. Con-

sequently, the high cost of production also affects the

final cost of the product to the consumers, impacting

to some extent the financial sustainability of the of the

independent studios that develop games.

5.4 Financial Resources

This code focuses on the investment/financing

sources for market-oriented products and academic

projects. In other words, terms involving investment

or financial or economic resource acquisition issues

belong to this code.

Regarding the financing from industry and

academia, the loss of resources for the execution of

the project can have a direct impact on the mainte-

nance capacity of institutions/companies. The way fi-

nancial resources raise, whether through public ten-

ders or private investments, also contributes to the

challenge. Public support is considered an essential

factor in this regard.

“Low public investment in the sector; im-

maturity of the national industry in gen-

eral, reducing the interest of private invest-

ment.” [P267]

A dependency between access to finance and prior

financial sustainability appeared. There is a specific

need for market stability to access some investments

Software Ecosystems and Digital Games: Understanding the Financial Sustainability Aspect

453

and, consequently, develop products that can make a

difference in the company sustainability. Bureaucracy

also contributes to the challenge of access to finan-

cial resources, despite the efforts of some government

agencies.

Exploring the relationship between funding and

public attraction shows a contradiction. Access to

public investment may be discouraging innovation in

the digital games industry and providing a false im-

pression of sustainability for some players.

“[...] the way the industry has gone in the di-

rection of using public edicts to maintain it-

self and not as a lever for the independence

of that industry.” [P40]

Some actors also claim that projects aimed at diver-

sifying audiences, such as educational games, have

easy access to financial resources. It suggests that di-

versification of use is a possible solution to the lack of

resources. In the same direction, development driven

to platforms with low investment needs can help to

outline the lack of financial resources.

5.5 Tax Burden

As seen in the two previous subsections, the tax bur-

den is part of the sector’s high production costs. In

some cases, it is a prerequisite for accessing financial

resources. The high import taxes, tariffs for receiving

from abroad and lack of government support for tax

incentives are examples of how tax burdens affect the

sustainability of national players.

5.6 Market Opportunity

The market opportunity brings together factors related

to business between companies and with the con-

sumer market. It joins reports of challenges regarding

consumption potential, economic scenario, interna-

tionalization, competition, production, and research

activities. The difficulty of taking advantage of the

opportunities that the market provides ultimately af-

fects the ability of players to remain active in the sec-

tor.

5.7 Attract Audience

The attraction of the target audience is associated with

how actors convince consumers to use their products.

Aspects of innovation, such as the creation of method-

ologies and the diversification of the consumer audi-

ence are addressed by this code.

This challenge is related to the high cost of the fi-

nal product to the consumer, the production of games

focused on marketing/dissemination, the lack of vis-

ibility of Brazilian products, the high production of

games for specific platforms (e.g. mobile), and the

lack of diversification of the audience beyond enter-

tainment.

The choice of specific platforms and the use be-

yond entertainment can make difference in financial

sustainability. Diversification of use influences the

access/need for financing and, consequently, the sus-

tainability of the actors.

“Many independent studios focusing on

mobile because of the ease and speed of de-

velopment [...]. We are still far from self-

sustaining.” [P62]

6 DISCUSSION

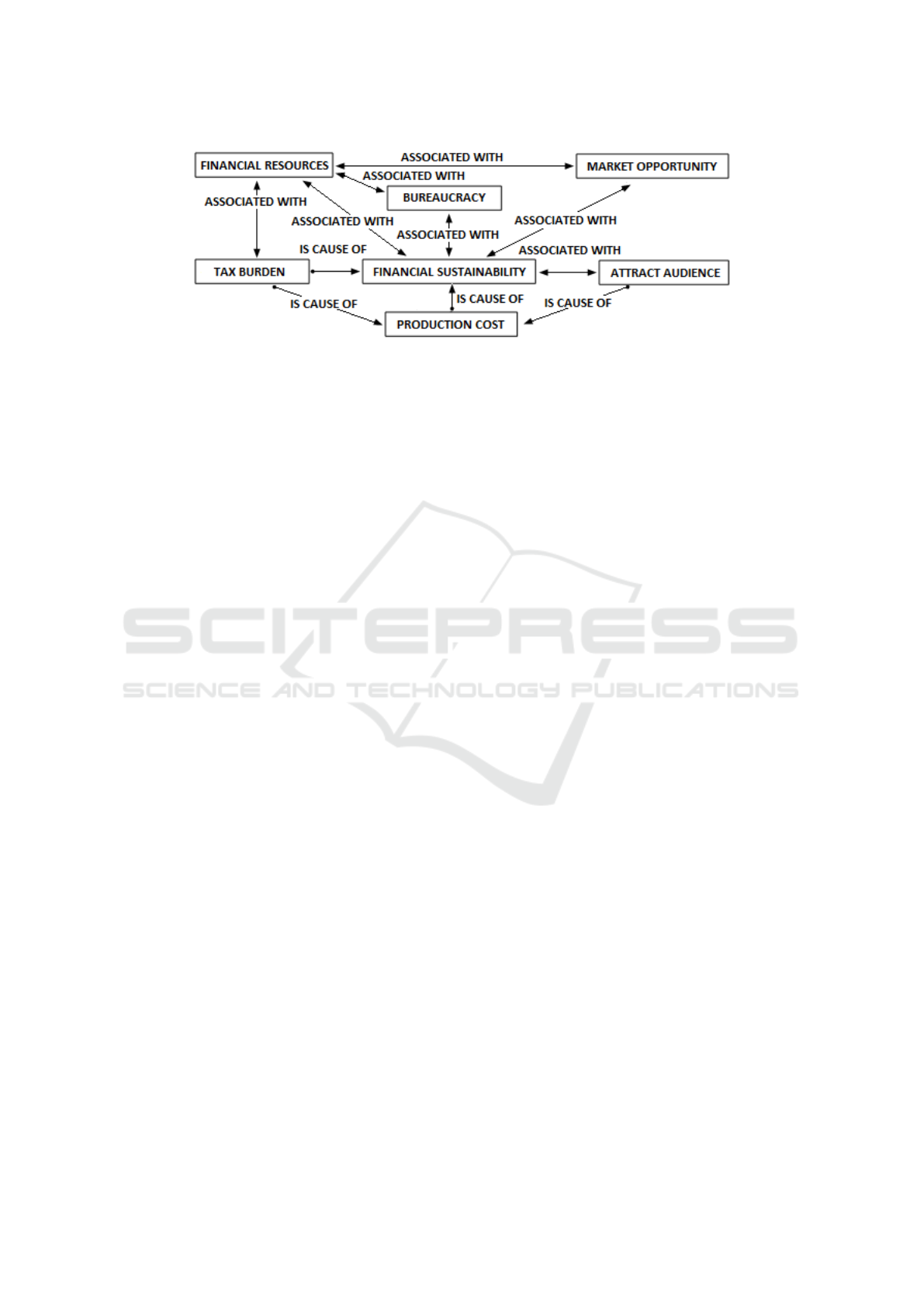

Figure 3 illustrates and typifies the relationships be-

tween the search codes. The lack of support in the

relationship between the actors and the holders of the

technological platforms is part of the national reality

of the digital games industry. The actors lack formal

support from such holders. However, they depend on

them to reach the target audience and achieve the fi-

nancial sustainability of their business.

Another definition that supports this relationship

is the concept of SECO sustainability. Sustainability

in this context encompasses business aspects (Dhun-

gana et al., 2010). The financial sustainability of the

actors that contribute to the promotion of a SECO

is part of this dimension. The high cost of pro-

duction (Martins et al., 2018; Sakuda and Fortim,

2018) makes this challenger harder when it comes to

the ongoing collaboration of actors towards SECO.

The lack of financial sustainability may result in the

change/loss of these actors, thus becoming a critical

factor for the overall sustainability of the involved

ecosystems.

As the main result of this research, it is possible

to mention the understanding of aspects that perme-

ate the actor’s financial sustainability in the game in-

dustry. It was observed that the challenge is related

to six others: bureaucracy, production cost, financial

resources, tax burden, market opportunities, and at-

traction of the target audience.

The approach of encompassing related challenges

in the analysis helps to observe the dynamics and be-

haviors. The flow between codes clarifies some pos-

sible points of action which, in turn, create research

opportunities. To understand this approach, it is nec-

essary to dive into these flows between the challenges.

The difficulty of staying financially healthy is as-

sociated with high production costs. In turn, the

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

454

Figure 3: Financial sustainability relationships.

high costs make it difficult to attract professionals and

maintain teams, impacting on the quality of projects

and devaluing the software product (digital game).

This cycle emerged thanks to the macro view and the

qualitative analysis applied in this study.

The choice of technological platforms, i.e. the

SECO to which a independent studio focuses its work,

was pointed out by P62 with a factor that influences

the execution of projects. Each platform has a form

of integration, and some tools from the game indus-

try (e.g., Unit, Unreal) facilitated the distribution of a

software solution (digital game) to several platforms.

However, this transposition does not happen for the

entire production process. This fact can be verified

by the preference for mobile platforms, due to speed

and ease in project execution. Despite the distribution

over several platforms, the choice of a SECO platform

influences in project execution, being a critical factor

for the independent studio’s sustainability.

A possible solution identified for financial sus-

tainability is the diversification of the use of digi-

tal games. Games that transcend only entertainment

emerged as a possible solution for raising financial re-

sources. On the other hand there is a need to stimulate

the acceptance of digital games in educational envi-

ronments. This contradiction of reports demonstrates

the lack of knowledge of some actors about the reality

of the national scenario of digital games. In the games

industry census (Fleury et al., 2014; Sakuda and For-

tim, 2018), it was highlighted such emerging state of

the area in Brazil. In other words, the actors of this

industry are in an early stage of playing in the market

and this is a fact that justifies the lack of knowledge of

the real problems or benefits of the national scenario.

Another point of reflection of relationships is in

project financing. In a shallow analysis, financing

could be a solution to the specific problem of financial

sustainability, providing flexibility for team mainte-

nance and other costs. However, as reported by P40,

access to this type of resource can have a reverse ef-

fect, giving some actors a false impression of success.

The strategy of pursuing investments until finan-

cial sustainability is a valid approach in some mar-

kets. However, as reported by P267, investors in

Brazil have high resistance to invest in the gaming

area, making this strategy unfeasible in the national

context.

The scope of this work also include academic re-

search. In the case of academic projects, the rela-

tionship with funding can be understood as essential,

since some academic research projects have no mar-

ket bias. Therefore, the concept of financial sustain-

ability is applied differently in these cases, requiring

a specific focus to meet the category of research insti-

tutions.

Access to equipment, software, and team main-

tenance are factors that contribute to the challenge

of production costs. The production cost also in-

cludes aspects of methodology, as reported by P62,

which highlights the complexity and project’s execu-

tion time as a factor that influences costs. Such code

exposes the need to define methodologies focused on

the profile of the national industry actors.

The difficulty in entering the national market itself

is a challenge that requires a specific investigation.

One of the reports points out the high cost to the final

customer as a possible motivation. However, this rea-

son does not explain the success of equally expensive

international products in the Brazilian scenario. An-

other factor linked to the execution of projects, which

may influence the acceptance of national products, is

the difficulty with marketing and dissemination ac-

tions. A methodology or model to support the plan-

ning of national studios at the business level can help

in related difficulties.

Another concept that supports the understanding

of the the digital games sector is that of the dimen-

sions of SECO (Santos and Werner, 2012; Barbosa

et al., 2013). Figure 4 frames the codes identified in

Table 1 Figure 3 among the SECO dimensions. By

observing the distribution of the codes, we can ob-

serve a concentration on the business dimension. In

other words, there is a need to a deep investigation on

Software Ecosystems and Digital Games: Understanding the Financial Sustainability Aspect

455

Figure 4: Challenges in the dimensions of SECO.

such dimension in the Brazilian digital games indus-

try.

The conduction of studies focused on business as-

pects needs to enter into different disciplined related

to this field. Studies supported by the Information

Systems area, together with concepts and theories

from other disciplines, such as Business and Software

Engineering, are fundamental to explore and propose

solutions to the identified challenges.

7 LIMITATIONS

Despite the number of participants, Brazil is a coun-

try with different realities within its territory. As a

consequence, it is not possible to generalize to a large

extent the results and analysis of this study. This ar-

gument also underlies part of the identified contra-

dictions, and there is a need for analyzing each local

community to achieve a deep understanding.

The data used in this study came from a survey

research whose objective is to identify benefits, prob-

lems, and challenges of the Brazilian digital games

industry. In turn, this work focused on exploring in

detail one of the several identified codes. Although

this strategy to explore a specific challenge, this ap-

proach did not take into account the impacts of indi-

rectly related aspects.

Communication via groups and social network

pages does not provide adequate control for the mea-

surement of participation rate, but this strategy en-

tirely agrees with the primary goal of our survey re-

search. As a consequence of the disclosure in groups

and social network pages, it was necessary to insert an

exclusionary factor as exposed by the question about

respondent’s profile (acedemy, industry, or both). Re-

sponses from actors who are not in one of this profiles

were discarded.

Regarding the qualitative analysis, it is necessary

to recognize the influence of the researchers’ knowl-

edge. Some short answers and direct citations of

terms with generic meanings may have an interpre-

tation bias. However, the analyses were verified in

several interactions with a third researcher to reduce

this bias and portray the identified results.

8 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Through a qualitative analysis of the survey data, it

was possible to identify six codes related to the chal-

lenge of financial sustainability code itself. Exploring

the relationships between the codes deepened the un-

derstanding of how the challenge is realized by the

participants. The perspective of SECO is an impor-

tant approach to achieve the objective of the study.

The growing digital games industry in Brazil

means that more people are venturing into SECO. The

sustainability of these ecosystems is crucial for new

players, which corroborates the importance of this is-

sue that has been addressed by both industry surveys

and academic studies.

The SECO vision helped us to explore and analyze

the Brazilian context from our study. Through this vi-

sion, it was possible to identify the importance of ex-

ternal actors in the sustainability dynamics. This work

contributes to the understanding of the dynamics of

digital games SECO and provides insights to aca-

demic research intertwining these two topics (SECO

and digital games).

As the main topic for future research, it was pos-

sible to identify a need to explore the business dimen-

sion of digital games SECO in Brazil. As a starting

point, it is necessary to explore the Business area to

identify points of intersection with this SECO dimen-

sion.

Another future work refers to the use of qualita-

tive approaches to deepen the understanding of the

relationships among the aspects of the digital games

industry. The Brazilian scope of out survey research

allowed us to highligh actors’s concerns in achieving

a big picture of the dynamics of the digital games in-

dustry - a fact that reinforce the importance of this

type of study.

Other suggestions for future work are: (1) use

other SECO concepts to support the analysis, such as

life cycle, health, and technical, human and organi-

zational factors; and (2) explore other codes related

to challenges, benefits, and problems identified in the

survey research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was financed in part by the Coordenac¸

˜

ao

de Aperfeic¸oamento de Pessoal de N

´

ıvel Superior –

Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001.

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

456

REFERENCES

Alves, C., de Oliveira, J. A. P., and Jansen, S. (2017). Soft-

ware ecosystems governance-a systematic literature

review and research agenda. In ICEIS (3), pages 215–

226.

Banaschak, P. (1999). Early east asian chess pieces: An

overview. Issue August.

Barbosa, O., Santos, R. P., Alves, C., Werner, C., and

Jansen, S. (2013). A systematic mapping study on

software ecosystems from a three-dimensional per-

spective. In Software Ecosystems. Edward Elgar Pub-

lishing.

Berg, N. (2015). Business model evolution in the game soft-

ware ecosystem. Master’s thesis.

Bosch, J. (2009). From software product lines to software

ecosystems. In SPLC, volume 9, pages 111–119.

Corbin, J. and Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative

research: Techniques and procedures for developing

grounded theory. Sage publications.

Dhungana, D., Groher, I., Schludermann, E., and Biffl, S.

(2010). Software ecosystems vs. natural ecosystems:

learning from the ingenious mind of nature. In Pro-

ceedings of the Fourth European Conference on Soft-

ware Architecture: Companion Volume, pages 96–

102.

Engstr

¨

om, H. (2019). Gdc vs. digra: Gaps in game produc-

tion research. In DiGRA 2019.

Finkel, I. L. (2007). On the rules for the royal game of ur.

Ancient Board Games in Perspective, pages 16–32.

Fleury, A., Sakuda, L. O., and Cordeiro, J. H. D. (2014). I

census of the brazilian digital games industry. NPGT-

USP e BNDES: S

˜

ao Paulo e Rio de Janeiro. (in Por-

tuguese).

Garc

´

ıa-Holgado, A. and Garc

´

ıa-Pe

˜

nalvo, F. J. (2018). Map-

ping the systematic literature studies about software

ecosystems. In Proceedings of the Sixth International

Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhanc-

ing Multiculturality, pages 910–918.

Jansen, S., Finkelstein, A., and Brinkkemper, S. (2009). A

sense of community: A research agenda for software

ecosystems. In 2009 31st International Conference

on Software Engineering-Companion Volume, pages

187–190. IEEE.

Kasurinen, J., Palacin-Silva, M., and Vanhala, E. (2017).

What concerns game developers? a study on game

development processes, sustainability and metrics. In

2017 IEEE/ACM 8th Workshop on Emerging Trends

in Software Metrics (WETSoM), pages 15–21. IEEE.

Manikas, K. (2016). Revisiting software ecosystems re-

search: A longitudinal literature study. Journal of Sys-

tems and Software, 117:84–103.

Manikas, K. and Hansen, K. M. (2013). Software ecosys-

tems - a systematic literature review. Journal of Sys-

tems and Software, 86(5):1294–1306.

M

¨

antym

¨

aki, M., Hyrynsalmi, S., and Koskenvoima, A.

(2019). How do small and medium-sized game com-

panies use analytics? an attention-based view of game

analytics. Information Systems Frontiers, pages 1–16.

Martins, G., Veiga, W., Campos, F., Str

¨

oele, V., David,

J. M. N., and Braga, R. (2018). Building educa-

tional games from a feature model. In Proceedings

of the XIV Brazilian Symposium on Information Sys-

tems, pages 1–7.

McKenzie, T., Trujillo, M. M., and Hoermann, S. (2019).

Software engineering practices and methods in the

game development industry. In Extended Abstracts

of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Inter-

action in Play Companion Extended Abstracts, pages

181–193.

Nahar, N., Huda, N., and Tepandi, J. (2012). Critical

risk factors in business model and is innovations of

a cloud-based gaming company: Case evidence from

scandinavia. In 2012 Proceedings of PICMET’12:

Technology Management for Emerging Technologies,

pages 3674–3680. IEEE.

Neto, B., Fernandes, L., Werner, C., and de Souza, J. M.

(2009). Reuse in digital game development. In

Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on

Ubiquitous Information Technologies & Applications,

pages 1–6. IEEE.

Sakuda, L. and Fortim, I. (2018). II census of the brazilian

digital games industry. (in Portuguese).

Santos, R. (2017). Ecossistemas de software no projeto e

desenvolvimento de plataformas para jogos e entreten-

imento digital. Anais do XVI SBGames, pages 2–4. (in

Portuguese).

Santos, R., Barbosa, O., Alves, C., et al. (2012). Software

ecosystems: trends and impacts on software engineer-

ing. In 2012 26th Brazilian Symposium on Software

Engineering, pages 206–210. IEEE.

Santos, R. and Werner, C. (2012). Reuseecos: An approach

to support global software development through soft-

ware ecosystems. In 2012 IEEE Seventh International

Conference on Global Software Engineering Work-

shops, pages 60–65. IEEE.

Serebrenik, A. and Mens, T. (2015). Challenges in soft-

ware ecosystems research. In Proceedings of the 2015

European Conference on Software Architecture Work-

shops, pages 1–6.

Shull, F., Singer, J., and Sjøberg, D. I. (2007). Guide to

advanced empirical software engineering. Springer.

Sormunen, J. et al. (2019). Sustainability of revenue models

and monetization of video games.

Stol, K.-J., Ralph, P., and Fitzgerald, B. (2016). Grounded

theory in software engineering research: a critical re-

view and guidelines. In Proceedings of the 38th Inter-

national Conference on Software Engineering, pages

120–131.

Toftedahl, M. and Engstr

¨

om, H. (2019). A taxonomy of

game engines and the tools that drive the industry. In

DIGRA International Conference 2019: Game, Play

and the Emerging Ludo-mix.

Software Ecosystems and Digital Games: Understanding the Financial Sustainability Aspect

457