National Cybersecurity Capacity Building Framework for Countries

in a Transitional Phase

Mohamed Altaher Ben Naseir

1

, Huseyin Dogan

1

, Edward Apeh

1

and Raian Ali

2

1

Bournemouth University, Fern Barrow, Poole, Dorset, BH12 5BB, U.K.

2

College of Science and Engineering, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Doha, Qatar

Keywords: National Cybersecurity Capacity, Business Process and Modelling Approaches, IDEF0.

Abstract: Building cybersecurity capacity has become increasingly a subject of global concern in both stable countries

and those countries in a transitional phase. National and international Research & Technology Organisations

(RTOs) have developed a plethora of guidelines and frameworks to help with the development of a national

cybersecurity framework. Current state-of-art literature provides guidelines for developing national

cybersecurity frameworks but, relatively little research has focussed on the context of cybersecurity capacity

building especially for countries in the transitional stage. This paper proposes a National Cybersecurity

Capacity Building Framework (NCCBF) that relies on a variety of existing standards, guidelines, and

practices to enable countries in a transitional phase to transform their current cybersecurity posture by

applying activities that reflect desired outcomes. The NCCBF provides stability against unquantifiable

threats and enhances security by embedding leading and lagging performance security measures at a

national level. The NCCBF is inspired by a Design Science Research methodology (DSR) and guided by

utilising enterprise architectures, business process and modelling approaches. Furthermore, the NCCBF has

been evaluated by a focus group against a structured set of criteria. The evaluation demonstrated the

valuable contribution of the NCCBF’s in representing the challenges in National Cybersecurity Capacity

Building and the complexities associated to the build.

1 INTRODUCTION

Over decades, the global cybersecurity environment

has been characterised by several security

insufficiencies, which have been defined as

government’s inability to meet their national

security obligations. Consequentially, security

failures can lead to state instability. Unstable and

transition phase countries often demonstrate

dramatic clear examples of unsuccessful governance

and public supervision failure (DeRouen et al.,

2012)

Generally, an unstable country or those in a

transition state are characterised by civil war;

political and economic upheaval; the absence of law

and the lack of a reliable body representing the state

beyond its borders at the inter-national level

(DeRouen et al., 2012; Naseir et al., 2019). For

example, we have witnessed the “Arab Spring”

states and their reoccurring transitions. These

transitioning states have tentatively gained

independence but lack stability towards national

solidarity and good governance. It is possible for a

group of people with tacit experience to organise

these states and lead them to stability (Kaplan,

2012).

Many countries with poor infrastructure and poor

governance are rapidly starting to establish their

presence in the cyberspace. However, this may

provide a new breeding ground for organised crime,

terrorism and being used as an instrument for

committing international cybercrime (Garlock,

2018). The increased prevalence cyberattacks and

cybercrime in these countries can be credited to

defenceless systems and lax cybersecurity practices

(Kshetri, 2019).

Research has shown that comprehensive

frameworks for cybersecurity are highly problematic

around the world (Donaldson et al., 2015; Oltramari

et al., 2014). Although there are many efforts

undertaken at national and international level,

building capacities of individual countries in

cybersecurity remains a challenge. Cybersecurity

Capacity Building (CCB) requires a horizontal

approach through different development strategy

fields, aiming to cultivate governance, securing

Ben Naseir, M., Dogan, H., Apeh, E. and Ali, R.

National Cybersecurity Capacity Building Framework for Countries in a Transitional Phase.

DOI: 10.5220/0009576708410849

In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS 2020) - Volume 2, pages 841-849

ISBN: 978-989-758-423-7

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

841

infrastructure, endorse the rule of law and providing

training (ISSEU, 2014).

This paper proposes a National Cybersecurity

Capacity Building Framework (NCCBF) for

countries in a transitional phase using Spring Land

as a case study. Spring Land is a fictional name

given to a country to provide a case study. The

framework relies on a variety of existing standards,

guidelines, and practices. The NCCBF progress is

guided and managed by utilising modelling

approaches.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 discusses the Cybersecurity Maturity

Models and Cybersecurity Capacity Building (CCB)

dimensions. The research method of the study is

presented in Section 3. Section 4 presents the

designing and developing of proposed framework,

and Section 5 discusses the evaluation of the

NCCBF. Finally, conclusions and future work are

presented in Section 6.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Cybersecurity Maturity Models

Increased attention to the potential risks and threats

of cyberspace to national security and their stability

has created a considerable demand for assessing and

reporting on the readiness of organisations and

countries using the Cybersecurity Capability

Maturity Models (CMMs) (Miron et al., 2014). The

CMMs deliver the stages for an evolutionary

pathway to developing strategies and policies that

will enhance the security and reporting of

cybersecurity capabilities of nations.

The state’s cybersecurity capacity is often

measured along with the criteria of legal, regulatory

and technical frameworks, coordination and

collaborations policies and the effectiveness of

government authority. One of the most recognised

models recently is Cybersecurity Capacity Maturity

Model (CCMM) for nations developed by the Global

Cyber Security Capacity Centre (GCSCC) at Oxford

University (GCSCC, 2017; Muller, 2015). This

model is offering a comprehensive analysis of CCB

through five different dimensions: Cybersecurity

Policy and Strategy; Cyber Culture and Society;

Cybersecurity Education, Training, and Skills; Legal

and Regulatory Frameworks; and Standards,

Organisations, and Technologies. Each dimension

includes multiple factors and attributes, each making

a significant contribution to CCB. Meanwhile, each

factor, involves five stages of maturity, with the

lowest indicator implying a non-existent, or

inadequate, level of capacity, and the highest

indicating both a strategic approach, and ability to

dynamically enhance against environmental

considerations, including operational, socio-

technical, and political threats (GCSCC, 2017;

Naseir et al., 2019). These dimensions were

employed to contextualise the problem space,

centred on the Spring Land case study and are used

as a lens to develop NCCBF for the country.

2.2 Cybersecurity Capacity Building

Dimensions from the World

Perspective (CCB)

Cyberspace has become an essential part of the

development of any country. A robust cybersecurity

capacity is vital for states to progress and develop in

economic, political and social spheres (Muller,

2015; Pawlak, 2014). Capacity building is

commonly viewed as a mechanism to bridge the gap

between the problems of poor governance and what

is considered to be an adequate level of state

capacity to deliver its main functions (Pawlak,

2016). Cybersecurity Capacity Building (CCB) is

complex and challenging (Trimintzios, 2017).

However, national and international organisations as

well as academics have developed a multiplicity of

guidelines and frameworks. These frameworks and

approaches indicate that there are five main pillars

that build cybersecurity capabilities: human,

organisational, infrastructure, technology, law and

regulation (Azmi et al., 2018).

These frameworks discuss global threats and

cybersecurity measures on the global level where

they primary focussed on stable and mature nations.

The literature review also illustrated insufficient

studies for developing countries due to the limited

technical capacity and lack of human capital (Tagert,

2010). Yet, despite growing attention from state

governments and international organisations, the

defence against attacks on national critical systems

has appeared to be fragmented and varies

considerably in terms of effectiveness (Atoum et al.,

2014). Muller (2015) argued that methods to date

have not managed to cover CCB as a whole on a

global scale or else they argue for CCB, without

indicating how to implement it.

Based on the literature review, despite

the

various perspectives and contexts for the

frameworks there are similarities shared across the

frameworks (Azmi et al., 2018). Some of these

include criteria such as, involving as many

stakeholders as possible and centralising competence

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

842

(Inclusive), promoting Fundamental of Human

Rights by recognising current International

Standards, Protocols and Interoperability (Coherent).

The framework should include Domestic and

International Tools such as Budapest Convention to

enhance international cooperation in tackling

cybercrime. Moreover, these frameworks encourage

states and organisations to develop cyber culture

programmes and adopt risk based approaches in

their national cybersecurity capabilities (ENISA,

2016; ITU, 2018; Klimburg, 2012). These shared

criteria and others are used to evaluate the proposed

framework in this study.

In this paper, we aim to enable policymakers to

define priorities for capacity building, utilising the

current maturity model (i.e. CCMM) developed by

GCSCC and its established five dimensions of

Cybersecurity Capacity Building (CCB) (GCSCC,

2017). The authors had selected this CCMM model

as a basis, because it successfully demonstrates the

global effects of a CCB solution - inclusive of all

areas cybersecurity for building a robust

cybersecurity platform.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

The overarching research approach used in this

paper is Design Science Research methodology

(DSR). The major principle of the DSR is that

knowledge and understanding of a design problem

and its solution are acquired in the building and

application of an artefact (Hevner et al., 2004). The

DSR research process carried out in this study

included five research activities as defined by the

design science method framework of (Johannesson

et al., 2014).

The first activity in DSR is to identify the initial

problem and the reason why the artefacts (in this

study the NCCBF for countries is transitional phase)

need to be developed and evaluated. The second

activity in the DSR process is to define the

objectives and the requirements for a solution.

In these two activities, Interactive Management

(IM) and Focus Group discussion approaches have

been used to analyse and review of the current state

of Spring Land’s cybersecurity capacity, by utilising

the CCMM for Nations as a baseline. A focus group

study was performed using this model with the

members (NCSA). The NCSA leads the

cybersecurity programme in Spring Land in terms of

technical, operational, and strategical level. In

addition, an IM technique was used. A one-day

Workshop hosted by NCSA was conducted for a

total of 26 participants representing various

stakeholders (Naseir et al., 2019).

The set of problem statements and objectives

derived from the IM approach has been employed to

support the management of a national cybersecurity

capacity in transitional state countries, similar to the

case study exemplar presented herein.

The third step in the DSR method was to design

and develop the artefact that addresses the identified

problem and defines objectives for a Solution (the

NCCBF). The NCCBF is guided and managed by

utilising a function modelling technique called

IDEF0, which is described in Section 4. The IDEF0

method is used to specify function models ('what to

do'). It is loosely based upon the Structured Analysis

and Design Technique (SADT) method developed

by Douglas Ross at SofTech in the 1970s (IDEF0,

1993; Noran, 2004). The main reasons for choosing

IDEF0 are its user capabilities in terms of

constructing and comprehending a model in addition

to superiority to many functional modelling methods

in terms of simple graphics, conciseness, rigor and

precision, consistent methodology, levels of

abstraction, and separation of organisation from

function (Cheng-Leong et al., 1999).

The fourth and fifth design activities are to

demonstrate and evaluate how well the artefact

solves the real-world problem taking into account

the previously identified objectives. We have

evaluated the NCCBF by conducting a focus group

with experts from different countries including

experts from countries that in transitional phase.

The participants were selected due to their

contributions in their decision-making in security

development from areas such as Defence, e-services,

Private Sector, Banking, Regulations of ICT sectors,

National cybersecurity agencies, Technical Advisor

and capacity Buildings, High Education, and

Integrated Digital applications. The results are

presented in Section 5.

4 DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

OF THE FRAMEWORK

This section defines the steps that were taken to

develop, the dimensions, functions, mechanisms and

controls for the proposed framework using IDEF0

modelling method. These steps address the

following question:

What can be developed to provide a National

Cybersecurity Capacity Building Framework

(NCCBF) for transitional state countries?

National Cybersecurity Capacity Building Framework for Countries in a Transitional Phase

843

The IDEF0 model presents a progression of the

steps that support the development of the (NCCBF).

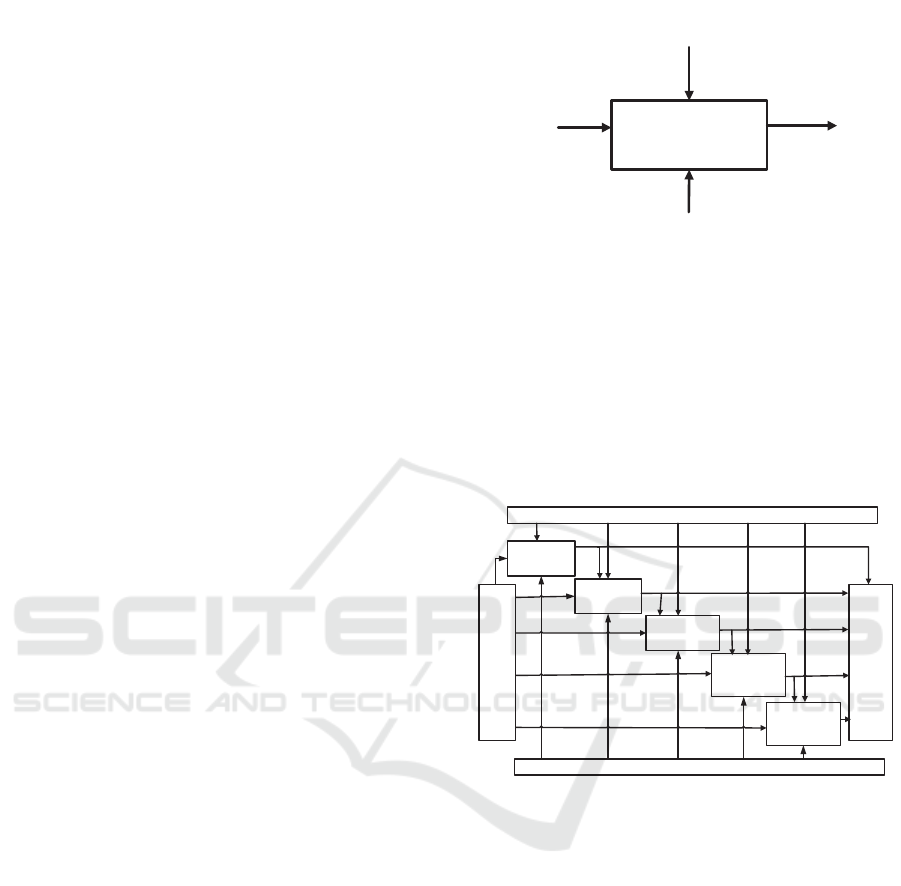

Figure 1 shows the top-level function of the

NCCBF. The inputs are the existing cybersecurity

maturity levels and the stakeholders’ views

concerning the issues relating to cybersecurity in

Spring Land (AS-IS). The output will be the

improved maturity level of Spring Land

cybersecurity (AS-TO-BE). The mechanisms are the

different types of resources; such as the cross-

functional team, systems, and technology that used

to support functions (activities) to achieve change.

The controls are tools or checklists that ensure

adherence to best practices such as the budget,

knowledge, and regulations. The mechanisms and

control statement template is created and explained

in the following section.

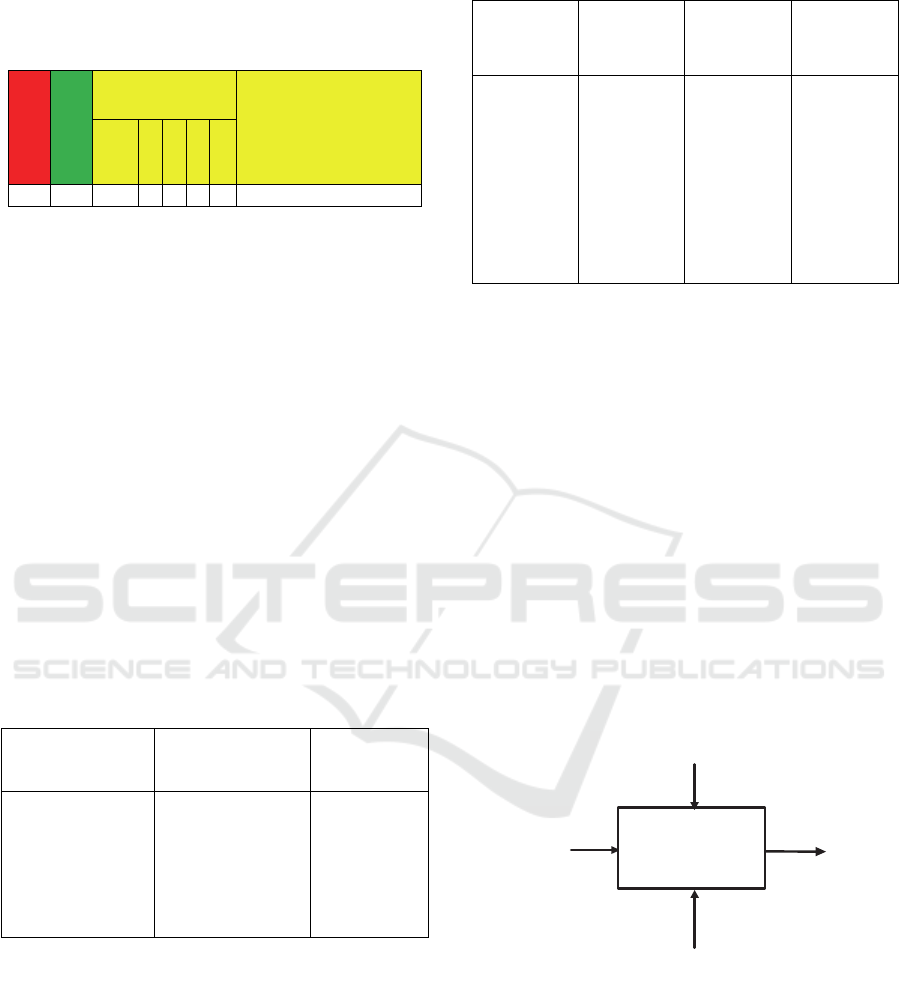

The top-level function of the NCCBF is

numbered A0 based on IDEF0. Subsequently, A0

activity is segmented into five activities

(dimensions) based on the CCMM model (GCSCC,

2017). These dimensions are presented in Figure 2

and summarised below:

Dimension one: build strategic capacity (D1).

This dimension looks at the steps required to

implement and review a national cybersecurity

strategy and the capacity in terms of incident

response, crisis management, critical

infrastructure protection, communications,

redundancy, crisis management and cyber

defence.

Dimension two: build cyber cultural and

society capacity (D2). This dimension covers

vital features of a cyber-culture across

stakeholders at the individual, public, private,

and societal levels that contribute towards

enhancement the maturity levels of the cyber

ecosystem.

Dimension three: build cybersecurity

Education, Training and skills capacity (D3).

This dimension is used to deliver essential

steps for cybersecurity education, training, and

skills development.

Dimension four: build legal and regulations

capacity (D4). This aspect offers a different

step required to form and update the national

legislation and laws relating to cybersecurity.

Dimension five: build technical capacities

(D5). This dimension discusses the CCB steps

that a country or organisation can implement to

employ cybersecurity standards, and at least

minimal adequate practices.

Outputs are target

C

y

bersecurit

y

levels

Inputs are Maturity

levels of NCS in

Spring Land ( AS-IS)

Mechanisms are different types of

resources; such as cross-

functional team, systems and

technology

A0

Develop NCCBF

Controls are budget,

knowledge, regulations and

Best Practices .

Figure 1: Top-level of NCCBF.

These dimensions are then decomposed to three

activities used to improve the capacity of each

dimension. The activities have been chosen based

on the most important objectives that were created

by various stockholders during the contextualising

and evaluation of the NCCB in Spring Land. More

details can be found in (Naseir et al., 2019).

D1

Build strategic

capacity

D2

Build cultural

capacity

D3

Build Education

and skills capacity

D4

Build legal

capacity

D5

Build Standards

and Technology

capacity

Mechanisms

Controls

Improved

Maturity

levels

(AS TO

BE)

Maturity

levels

(AS-IS)

Figure 2: The NCCBF Activities.

4.1 Input Statement Template

This template is based on CCMM to review the key

issues related to the cybersecurity capacity of Spring

Land. These findings provide the basis for the

requirements of the NCCBF for countries in a

transitional. Table 1 illustrates the dimension and

factors that are used in the input template.

Each dimension includes multiple factors and

attributes (GCSCC, 2017), each making a significant

contribution to capacity building. Each factor,

involves five stages of maturity (Start-Up (S-UP),

Formative (F), Established (E), Strategic (S) and

Dynamic (D). The lowest indicator implies a non-

existent, or inadequate, level of capacity, and the

highest indicates both a strategic approach, and

ability to dynamically enhance environmental

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

844

considerations, including operational, socio-

technical, and political threats.

Table 1: Input template statement.

Dimensions

Factors

Indicators

Challenges and issues

S-

UP

F E S D

4.2 Dimensions and Functions

Statement Template

As described in Section 4, in IDEF0 models the

whole top-level function is segmented into sub-

function parts. In this study, the Dimension ID is

used to describe the top level activity name for each

dimension of the NCCBF based on the five

dimensions of the CCMM. Table 2 presents the

template statement that was used to create the

functions for each dimension and the interaction of

each activity with other activities in the same

dimension of other dimensions.

Function ID is used to describe the activities or

the processes required for NCCB in each dimension.

The function statements were created based on the

stakeholders’ view from within the case study

country and the existing national cybersecurity

frameworks (Naseir et al., 2019).

Table 2: Functions statement template.

Dimension ID

Function ID and

description

(Activities)

Interactions

Used to identify

the name of the

dimension.

Used to identify

the name of the

function and

describe its

purpose.

Used to

indicate the

interactions

of a given

activity with

other

activities.

4.3 Mechanisms and Controls

Template Analysis

This template is used to capture related mechanisms

and controls for each dimension. The mechanisms

are the different types of resources such as the cross-

functional teams, systems and technology that are

used to support functions (activities) to achieve

change.

Table 3: Mechanisms and Controls Template.

Mechanism

ID and

description

Rational of

the

mechanism

Control ID

and

description

Reference

and Access

Identifies

and

indicates the

function that

the

mechanism

is related to.

Describes

the

motivation

to use the

mechanism

Identifies the

mechanism

that the

selected

control is

related to.

Identifies the

milieu of the

selected

supporting

material and

whether it is

considered

to be open

source or

proprietary.

The controls are tools or checklists that ensure

adherence to best practices such as the budget,

knowledge and regulations.

The next section provides a description of the

steps taken to build the strategic capacity in the

proposed framework using the template statements

described in previous section. The other dimensions

of the NCCBF are not presented here because of the

need for brevity in this paper.

4.4 Dimension (D1): Build Strategic

Capacity

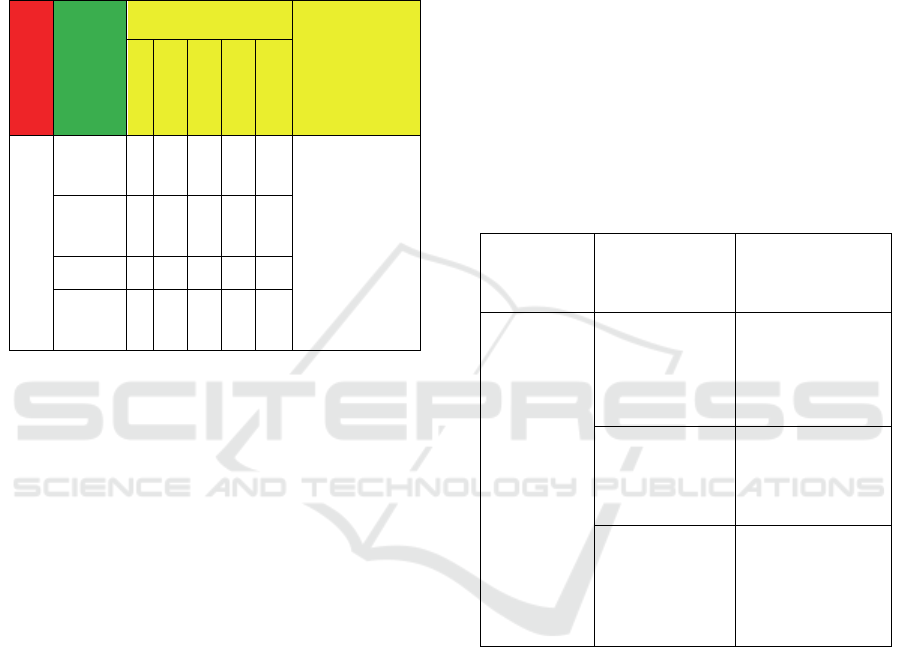

According to the CCMM this dimension looks at the

crucial steps required to implement and review

national cybersecurity strategy capacity. The top

level activity (D1) is represented using IDEF0 as

shown in Figure 3.

Improved

maturity levels

Current

maturity levels

Mechanisms

(M1.1.1,M1.1.2,…..M1.3.3)

D1

Build strategic

capacity

Controls

(C1.1.1,C1.1.2….C1.3.3)

Figure 3: Top level activity for D1.

4.4.1 Input Statement Template for

Dimension One (D1)

In this stage we review the maturity levels and key

issues related to cybersecurity policy and strategy

capacity in Spring Land using input template

analysis. As stated in the research method section,

two qualitative approaches have been used to

National Cybersecurity Capacity Building Framework for Countries in a Transitional Phase

845

analyse and review the current state of Spring

Land’s cybersecurity capacity. Table 4 provides an

example of how the input template statement is used

to capture the challenges encountered by various

stakeholders in Spring Land and the maturity level

of certain factors related to this dimension.

Table 4: Example of Maturity levels and Challenges in D1

of the NCCBF.

Dimensions

Factors

Indicators

Challenges

and issues

(Naseir et al.,

2019)

S

-

U

P

F E S D

D1

D1.1

*

Lack of a

national

cybersecurity

strategy and

unavailability

of a national

risk

management

plan.

D1.2

*

D1.3 *

D1.4 *

D1 refers to dimension one, D1.1 concerns the

national cybersecurity strategy maturity level, D1-2

indicates the incident response capabilities maturity

level, D1-3 refers to the critical national

infrastructure (CNI) Protection maturity level and

D1-4 indicates crisis management maturity level.

The outcomes of this stage show that the maturity

level of this dimension can be classified from start-

up to formative stages. For instance, the organisation

leading the cybersecurity programme and national

CERT in Spring Land has been identified.

Furthermore, one of the most significant findings to

emerge from this assessment is that Spring Land

does not have a blueprint for a cyber defence

strategy in place as result of political fragmentation.

This means that raising the level of maturity of these

factors helps to fill certain gaps in the Spring Land’s

cybersecurity ecosystem.

4.4.2 Functions Statement Template for

Dimension One (D1)

The functions statement template was expalined in

Section 4.1.2. The functions are used to improve the

CCB in this dimension were chosen based on the

stakeholders’ view from within the case study

country and the existing national cybersecurity

frameworks (Naseir et al., 2019). To create these

functions and establish the interaction between them

a function template statement is used as shown in

table 5.

The purpose of the NCS is to provide direction

and framing for national policies and actions

pertaining to cybersecurity over the medium-to-long

term (Bellasio et al., 2018; ENISA, 2016; ITU,

2018). The NCS is important because state

interactions in cyberspace are characterised by

uncertainty, rather than predictability of this era. To

develop the NCS it is necessary to go through a

number of mechanisms and controls that which are

described in the next section. Once developed the

function will support other functions such as D1.2

and D1.3 because it will guide the preparation and

enforcement of other functions. In addition, it

depends on national legal framework the outcome of

dimension two in the NCCBF.

Table 5: List of functions used in D1.

Dimension

ID

Functions ID

and description

(Activities )

Interaction

D1. Build

strategic

capacity

D1.1 Develop

NCS.

Supports

D1.2,D1.3

Depends

on D2

D1.2 Building a

Risk

management

approach

Supports D1.3

Depends on

D1.1

D1.3 Building a

National

Incident

Response

Capabilities

Depends on

D1.3, D2

Building a risk management approach helps to

identify and prioritise the risks facing the Critical

National (CI) assets and critical National

Information infrastructure (CNI) (Bellasio et al.,

2018). A different set of mechanisms and controls

are used to develop a

risk management approach and

this is elaborated in the next section.

Building national incident response capabilities

is another function used to build the CCB of the

country. It allows government to identify national-

level cyber incidents and coordinate a response to

ensure that harm is contained, the attacker is no

longer present, and the functionality and integrity of

the network and system are restored (Bellasio et al.,

2018; ENISA, 2016; ITU, 2018).

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

846

4.4.3 Mechanisms and Controls Template

Analysis for Dimension One

This template is used to capture related mechanisms

and controls for building strategic capacity based on

existing best practices, global cybersecurity

frameworks. Table 5 shows how mechanisms and

controls are defined and represents the justifications

and rationale for the selected ones. For instance, to

develop function (D1.1 Develop NCS), an

establishment of a National Council for

Cybersecurity with a clear mandate, appropriate

statutory powers, and an organisational structure is

required (M1.1.1).

Table 6: Example of mechanisms and controls template

for D1.

Mechanism

ID

Rational Control ID

Reference

and Access

M1.1.1

Establish a

national

council

Performs

a crucial

function

in

coordinati

ng across

different

organisati

ons in the

state.

C1.1.1,

Regulatory

framework

,assignment

chart ,

Advisory

group,

counter-

terrorism

committee

and EA

governance

RACI

matrix is

open source.

COBIT 5 is

not free, the

proprietary

rights are

from

ISACA,

(www.isaca.

org)

The rationale for creating the council is to

perform a crucial function in coordinating across

different organisations in the public and private

sectors. Also, forming a strong leadership role at the

highest level contributes to recognition of the NCS.

To some extent, the national cybersecurity council

will be expected to steer a complex environment that

spans other government sectors, national

legislatures, established regulatory authorities, civil

society groups, public and private sector

organisations, and international partners. It is also

critical that the responsibilities of the national

cybersecurity agency are distinct from those of other

governmental groups involved in cybersecurity

(Ciglic, 2018; ITU, 2018).

The roles and responsibilities can be defined

using an assignment chart such as the RACI matrix

that maps out every task, and assigns roles are

Responsible for each action item, the personnel

who are Accountable, and, who needs to be

Consulted or Informed (CTO, 2015). This matrix

can be used with the Enterprise governance of IT, as

defined through COBIT 5 (ISACA, 2013), as a

control tool (C1.1.1) to ensure adherence to best

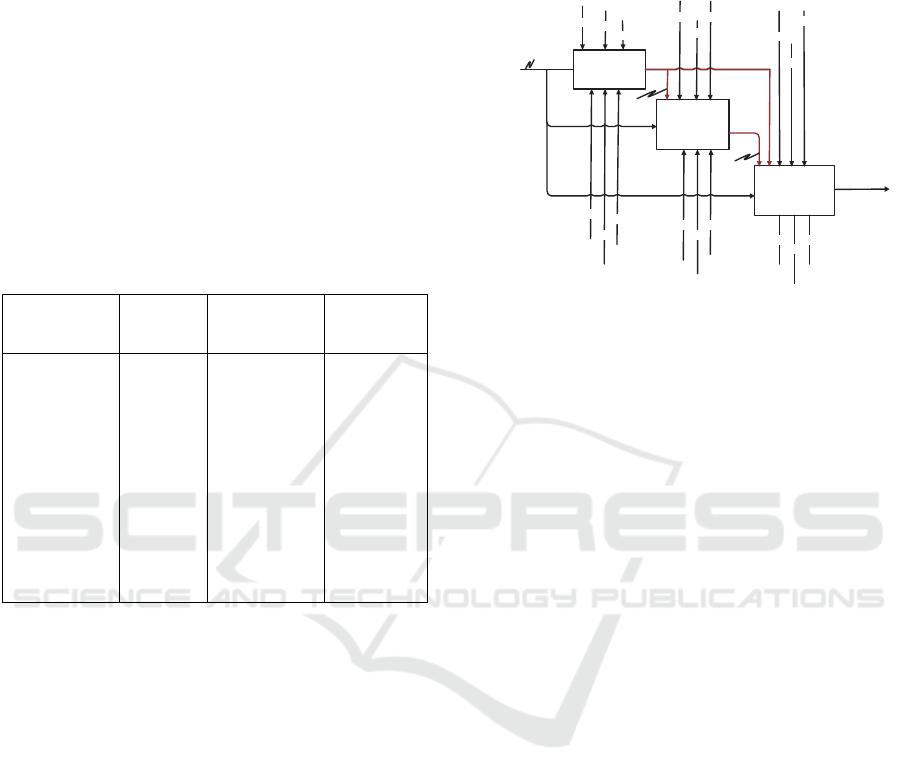

practice. After capturing the required functions,

mechanisms and controls, we represent these

activities using IDEF0 (see Figure 4).

D1.1

Develop NCS.

D1.2

Building a Risk-

based approcah

D1.3

Building National

Incident Response

Capabilities

M1.2.1

M1.2.2

M1.2.3

C1.1.3

M1.3.3

M1.3.2

M1.3.1

M1.1.3

M1.1.2

M1.1.4

Maturity levels

&

challenges

O1.1

C1.3.1

C1.3.2

C1.3.2

Improved

maturity levels

Interaction

(Support)

Inte raction

(Support)

C1.2.3

C1.2.3

C1.2.1

C1.1.2

C1.1.2

Figure 4: Dimension 1 functions.

5 EVALUATION

Based on the results from the research as described

above, an IDEF0 model is created. This method has

been validated by 13 experts in the field the

cybersecurity from different countries including

experts from countries that in transitional phase,

during a workshop session by using the focus group

technique.

The experts were given a brief presentation about

of the NCCB. In addition, plain text versions of the

framework description were given with a set of

questions used for the evaluations. After the

presentation, the experts were asked to form groups

of 2 or 3 persons, resulting in 4 groups. Each group

was given a form with two questions about the

completeness, four questions about the correctness,

and two questions about the acceptability of the

framework. Also, there was one question to evaluate

the NCCBF based on a set of requirements was

given to them.

These requirements have been discused in Section

2.2 and have been used as the basis to evaluate the

resulting artefacts and guide the construction process

in addition to any refinement steps. The group of

experts was asked to answer the questions within a

90 minute time span.

5.1 Key Findings from the Evaluation

The response from the workshop session primarily

revealed that:

Some activities were missing. For instance, all

of the experts mentioned that in the AS-IS step

National Cybersecurity Capacity Building Framework for Countries in a Transitional Phase

847

we should consider other methods to evalaute

the internal and external landscape such as

SWOT and PESTEL approaches. Also, eight

of the

experts clearly confirmed that the

financial resources and how to obtain the

funding are missing in the NCCBF. Moreover,

nine experts confirmed that cooperation in case

of instability and during crises is missing and

we have to create coordinated mechanisms

with regional and international partners.

All experts mentioned that some activities

should be added to the framework such as,

Performance measurements,

auditing

mechanisms to be added to legal capacity

building.

Moreover, all of participants stated to use the

NCS as function not as a mechanism and swap

it with “Establish a National Council”. Another

interesting point is that all of the participants

stressed that the national council should

include the advisory committee and counter-

terrorism committee.

Ten experts from thirteen , agreed that this

farmework is “useful and acceptable”. Two of

them said that, they liked how the capacity

building in educations and private sectors has

been defined and developed.

All of the participants acknowledged that the

framework is inclusive, coherent,multi-

dimensional and risk based.Four of them

commented that in their opinion this

framework is inclusive, coherent, multi-

dimensional and risk-based because it is based

on a well know and internationally acceptable

model (CCMM).

6 CONCLUSION AND

FUTUREWORK

In this paper, a National Cybersecurity Capacity

Building Framework (NCCBF) is proposed to

enable countries in a state of transition to transform

their current cybersecurity posture by applying

activities that reflect desired outcomes. The NCCBF

provides the means to better understanding how

NCCB can be defined and developed.

The future

work will invovle refinement to the components of

the framework such as using performance

measurement techniques to monitor the performace.

In addition, the Enterprise Architecture components;

a framework, a method, and a language (modelling)

(Iacob et al., 2012) will be used used in the proposed

CCB framework. The framework will be validted

after the enhancement using international

cybersecurity indexes that measure the NCB. In

addition, logical operators will be used for parallel

execution of functions and output templates to

improve the IDEF0 models.

REFERENCES

Atoum, I., Otoom, A., & Ali, A. A. (2014). A holistic

cyber security implementation framework.

Information Management & Computer Security.

Azmi, R., Tibben, W., & Win, K. T. (2018). Review of

cybersecurity frameworks: context and shared

concepts. Journal of Cyber Policy, 3(2), 258-283.

Bellasio, J., Flint, R., Ryan, N., Sondergaard, S.,

Monsalve, C. G., Meranto, A. S., & Knack, A. (2018).

Developing Cybersecurity Capacity: A proof-of-

concept implementation guide.

Cheng-Leong, A., Li Pheng, K., & Keng Leng, G. R.

(1999). IDEF*: a comprehensive modelling

methodology for the development of manufacturing

enterprise systems. International Journal of

Production Research, 37(17), 3839-3858.

Ciglic, K. (2018). Cybersecurity Policy Framework A

practical guide to the development of national

cybersecurity policy. Retrieved from https://www.

microsoft.com/en-us/cybersecurity/content-hub/cyber

security-policy-framework

CTO. (2015). Commonwealth Approach for Developing

National Cybersecurity Strategies: A Guide to

Creating a Cohesive and Inclusive Approach to

Delivering a Safe, Secure and Resilient Cyberspace:

Commonwealth Telecommunications Organisation

(CTO) London, UK.

DeRouen, K., & Goldfinch, S. (2012). What Makes a State

Stable and Peaceful? Good Governance, Legitimacy

and Legal-Rationality Matter Even More for Low-

Income Countries. Civil Wars, 14(4), 499-520.

doi:10.1080/13698249.2012.740201

Donaldson, S. E., Siegel, S. G., Williams, C. K., & Aslam,

A. (2015). Cybersecurity frameworks Enterprise

Cybersecurity (pp. 297-309): Springer.

ENISA. (2016). NCSS Good Practice Guide,Designing

and Implementing National Cyber Security Strategies.

Retrieved from https://www.enisa.europa.eu/

publications/ncss-good-practice-guide.

Garlock, K. (2018). Maturity Based Cybersecurity

Investment Decision Making in Developing Nations.

The George Washington University.

GCSCC. (2017). Cybersecurity Capacity Maturity

Model for Nations (CMM) Retrieved from

https://www.sbs.ox.ac.uk/cybersecurity-

capacity/system/files/CMM%20Version%201_2_0.pdf

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., & Ram, S. (2004).

Design science in information systems research. MIS

quarterly, 75-105.

ICEIS 2020 - 22nd International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

848

Iacob, M.-E., Quartel, D., & Jonkers, H. (2012). Capturing

business strategy and value in enterprise architecture

to support portfolio valuation. Paper presented at the

2012 IEEE 16th International Enterprise Distributed

Object Computing Conference.

IDEF0. (1993). Draft Federal Information Processing

Standards Publication 183: Announcing the Standard

for Integration Definition For Function Modeling

(IDEF0).

ISACA. (2013). Cybersecurity Nexus: Transforming

Cybersecurity: Information Systems Audit and Control

Association (ISACA) Illinois, USA.

ISSEU. (2014). Cyber Capacity Building as a

Development Issue: What Role for Regional

Organisations?

https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFil

es/Cyber_event_brochure.pdf

ITU. (2018). Guide to Developing a National

Cybersecurity Strategy. Retrieved from https://www.

itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/str/D-STR-CYB_GUIDE.01

-2018-PDF-E.pdf

Johannesson, P., & Perjons, E. (2014). An introduction to

design science: Springer.

Kaplan, S. (2012). Differentiating Between Fragile States

and Transition Countries. Fragile States, June 2012.

Klimburg, A. (2012). National cyber security framework

manual.

Kshetri, N. (2019). Cybercrime and Cybersecurity in

Africa: Taylor & Francis.

Miron, W., & Muita, K. (2014). Cybersecurity capability

maturity models for providers of critical infrastructure.

Technology Innovation Management Review, 4(10),

33.

Muller, L. P. (2015). Cyber security capacity building in

developing countries: challenges and opportunities.

Naseir, M. A. B., Dogan, H., Apeh, E., Richardson, C., &

Ali, R. (2019). Contextualising the National Cyber

Security Capacity in an Unstable Environment: A

Spring Land Case Study. In World Conference on

Information Systems and Technologies(pp.373-382).

Springer, Cham.

Noran, O. (2004). UML vs. IDEF: An Ontology-Oriented

Comparative Study in View of Business Modelling.

Paper presented at the ICEIS (3).

Oltramari, A., Ben-Asher, N., Cranor, L., Bauer, L., &

Christin, N. (2014). General requirements of a hybrid-

modeling framework for cyber security. Paper

presented at the 2014 IEEE Military Communications

Conference.

Pawlak, P. (2014). Riding the Digital Wave: The impact of

cyber capacity building on human development: EU

Institute for Security Studies.

Tagert, A. C. (2010). Cybersecurity challenges in

developing nations.

Trimintzios, P. (2017). Cybersecurity in the EU Common

Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). Challenges and

risks for the EU. Brussels: Scientific Foresight Unit

(STOA), European Parliamentary Research Service,

European Parliament.

National Cybersecurity Capacity Building Framework for Countries in a Transitional Phase

849