Features for an International Learning Environment in Research

Education

Barbara Class

a

Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, TECFA, University of Geneva,

40, Boulevard du Pont-d'Arve, CH-1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland

Keywords: Learning and Teaching Environment, Research Education, Knowledge Economy, SDG4.

Abstract: This position paper is written at the very start of a SNF funded project on research education in the social

sciences. We present a preliminary model for an international learning and teaching environment for PhD

students in education. Based on a conceptual framework drawing on research and open education, virtual and

scientific mobility, articulated to the broader concept of the knowledge economy, the model is fivefold. It

addresses pedagogical and technological issues, suggests a dual tutoring system to accompany PhD students,

promotes virtual scientific mobility and is connected to viable and fair economic and institutional

surroundings. The paper interprets SDG 4 widely, suggesting early integration of young researchers into

international scientific networks can contribute to address contextual and global educational challenges

intelligently.

1 INTRODUCTION

The overall objective of this position paper is to

present possible avenues for an international learning

environment in research education. The environment

is designed for PhD students in the social sciences and

particularly in the field of education and digital

education.

Education as a concept presupposes, on the

cognitive level, one possesses a body of knowledge

as well as conceptual schemes that lead to an

understanding of underlying organisations of facts. It

also refers to connecting to a wider system of beliefs

rather than being limited to the training of given skills

(Peters, 1966). In the same line of thought, education

is to be understood as a “focus for inquiry” (Bridges,

2017, p. 15) and not as a discipline.

As far as research on education is concerned,

educational research is massive and diverse. It relies

on “methods and methodologies on every part of the

academy (as well as other spheres of social and

professional practice)” (Bridges, 2017, p. 2).

When it comes to research education,

practitioners and young researchers often say that

methodology courses usually do not come at the right

time in the curriculum and/or that they are inadequate

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5461-2307

in terms of learning outcomes (e.g. Attia & Edge,

2017).

To address this issue and the need for “just in

time” methodological content and tutoring, a small-

scale initiative, taking the form of on-line modules in

research methodology, was piloted during the

academic year 2018-9. This initiative is rooted in the

specific context of an exceptional scientific growth

attested in North Africa, which, as a corollary

increases the demand for methodology education

(Waast & Gaillard, 2018). It mixed francophone PhD

students from the North and from the South and was

the occasion to highlight key strengths and

weaknesses of these on-line modules which were

offered in the form of free continuing education

without formal assessment or certification.

Drawing on that experience, the specific goals of

this contribution consist in presenting features for an

improved learning and teaching online environment

that offers certification. Research education, open

education and scientific virtual mobility, articulated

to the knowledge economy as a conceptual

framework, represent the bedrock on which this paper

unfolds.

488

Class, B.

Features for an International Learning Environment in Research Education.

DOI: 10.5220/0009572904880494

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 1, pages 488-494

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 The Knowledge Economy

In 1999, the Bologna reform and its eponymous

declaration formally launched the knowledge society.

Its goal was to transform the European Union into the

most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based

economy by 2010 (Huisman, Adelman, Hsieh,

Shams, & Wilkins, 2012). The levers to reach this

goal are materialised in the European Higher

Education Area (EHEA) and consist in i)

restructuring courses in 3 levels (Bachelor, Master,

PhD); (ii) establishing transparency, compatibility

and mutual recognition of course credits with the

means of European Credit Transfer System (ECTS);

(iii) implementing a quality assurance system,

vehicled by qualification frameworks; iv)

encouraging mobility with the Diploma Supplement

and Learning Agreements for Studies; and (v)

realigning higher education to meet the needs of a

globalised knowledge economy (Bachmann, 2018;

Buchem et al., 2018). The initial inter-governmental

process quickly evolved into multi-level governance

involving a myriad of actors and very soon expanded

to southern Mediterranean countries. In 2003, North

Africa was identified as a priority area in order to

create a Euro-Mediterranean job market, transparent

in terms of qualifications (Huisman et al., 2012).

2.2 Research Education

Teaching research methodology in the social sciences

is still lacking a common pedagogical culture (Earley,

2014; Kilburn, Nind, & Wiles, 2014; Wagner,

Garner, & Kawulich, 2011), three interrelated

pedagogical goals prove more efficient than others

and consist in i) making the research process visible

by actively engaging learners in real research; ii)

actually conducting research to take ownership and

understand what research is; and iii) reflecting

critically about the learning experience (Lewthwaite

& Nind, 2016; M. Nind & S. Lewthwaite, 2018; M

Nind & S Lewthwaite, 2018). At a finer granularity,

research teaching pedagogy got interested into

activities teachers and learners may engage in

(Dawson, 2016) and classified these from the

philosophical foundations of teaching approaches to

the actual classroom activities (Nind & Lewthwaite,

2019). Following these recommendations, research

methodology education necessitates small scale

courses and proximity tutoring.

In terms of training, early career researchers seek

active involvement in trainings they are the

beneficiaries of to gain ownership (Barnard,

Mallaband, & Leder Mackley, 2019) and publishing

remains their main concern (Mabe, 2010 cited by

Nicholas et al., 2017). Solid training and critical

thinking towards methodological practices are of

foremost importance in such a context and should

avoid adopting questionable research practices (John,

Loewenstein, & Prelec, 2012) and allow detecting

them.

2.3 Open Education

To be successful, open education infrastructure must

support all 4 interdependent components: open

competencies, educational resources, assessment and

credentials (Wiley, 2017). In addition, it must support

open admission and open education practices

(Cronin, 2017).

Open competencies exist in isolated formats in

different parts of the open web. An effort to

synthesise and map the competencies doctoral

students in education should master in 2020 and in the

future still needs to be done. To achieve this, some

sound and in-depth work, based on a comprehensive

review of existing competence frameworks (e.g. Van

der Maren, Brodeur, Gervais, Gilles, & Voz, 2019) in

different languages, and added with prospective and

visionary approaches, should be conducted.

To develop identified competences, learning

assets should comply with open education and

particularly fall within open educational resources

(OER). OER are defined as “teaching, learning and

research materials in any medium – digital or

otherwise – that reside in the public domain or have

been released under an open license that permits no-

cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by

others with no or limited restrictions” (UNESCO

2017 cited by UNESCO, 2019, p. 9). This definition

has reached a certain consensus but many issues

tackled by research remain unsolved, among which

models of sharing and producing OER for instance

(Wiley, Bliss, & McEwen, 2014). OER “come with

an irrevocable grant of permission to engage in the 5R

activities – retain, reuse, revise, remix, and

redistribute” (Wiley, 2017, p. 196) and concrete

solutions are experimented. The surrounding setting -

institutions, laws, policies, economy, technology –

must be ready and supportive (Döbeli, Hielscher, &

Hartmann, 2018) for OER to have a chance to grow.

Blockchain might offer technological solutions

for open assessment and credentials (Anderberg et al.,

2019; Grech & Camilleri, 2017; Müller, 2020) and

new experiences need to be carried out. More

conceptually speaking, evaluation is to be rethought

in relationship to practice and resource rich

environments (Halbherr & Kapur, 2019).

Features for an International Learning Environment in Research Education

489

Open credentials refer to learner-owned

certification that can be remixed to feature a learner's

expertise according to contextual demands. Tamper-

proofed open credentials are the basis to establish

trust and retrace the origin of a validation (Wiley,

2017).

Open admission refers to admitting learners

without institutional entry requirements (i.e. prior

diploma). In reference to Hart (1992)’s learner

participation ladder, open educational practices refer

to levels 7 and 8 in which learners and teachers design

together an education project and co-create

knowledge processes (Cronin, 2017). Co-creation

poses the question of practicing and valuing virtual

scientific mobility in open education.

2.4 Virtual Mobility

At a normative level, online international learning is

discussed as “a non-discriminatory alternative of

mobility” (Buchem et al., 2018, p. 352), that should

be implemented institutionally, within any

curriculum of the EHEA.

In practice, though, a lack of knowledge on how

to actually implement it and of its efficiency in terms

of learning outcomes are obstacles to spread it. The

aim of the European Virtual Mobility Learning Hub,

within the current Open Virtual Mobility project,

precisely consists in suggesting a realistic framework.

It will be based on open education and promote

achievement, assessment and credentialing of virtual

mobility skills.

Some higher education institutions have already

integrated virtual mobility in their curricula and

formalised requirements for course designers that

recommend i) engaging with international peers on

content; ii) designing internationalised learning

outcomes informed collaborative activities; iii)

nurturing reflection on the learning that ensued from

the intercultural encounter (Villar-Onrubia & Rajpal,

2016).

In North Africa, a recent Erasmus+ project, called

OpenMed, reports an online international learning

experience and findings show, among other things,

that readiness to adopt open education is related to the

degree of internationalisation of institutions; that

clear learning activities promote collaboration both at

the local and international levels; and that differences

in academic traditions drawing back to respective

French and English influences exist between the

Maghreb and the Middle East (Nascimbeni et al.,

2018).

Virtual (Deardorff, de Wit, Heyl, & Adams, 2012)

and scientific mobility (Boekholt, Edler,

Cunningham, & Flanagan, 2009; Gaillard & Bouabid,

2017) are key for the development of the researcher,

institutions involved and countries. Thus, scientific

mobility should definitely be part of any learning

environment in research education. The concept of

“intelligently internationalised researcher” refers to

seeking for cross-country collaborations and risk

taking in order to establish some scientific equity in

the world (de Gayardon, 2019).

2.5 Contextual and International

Tutoring

Learner support is a key issue in the entire learning

and teaching design process. It should be aligned with

the overall objectives and underpinning

epistemologies of the learning environment. Tutoring

can thus be said to be situated, physically and at a

distance, to support the three key moments of

intervention. The first is in the beginning of the

learning experience, to negotiate and establish a

relationship based on trust. The second is during the

learning process by providing valuable, timely and

regular formative feedback. And the third is at the end

to retrace the entire learning process and help move

the experience forward. In addition, tutors make use

of a set of tools – cognitive as well as technological –

and engage into some form of continuing education

to remain up-to-date (Class, 2009).

Designing tutoring support that comprehends a

local and a distant component is of utmost importance

in research methodology training (Class, 2019). The

local tutor plays a fundamental role in introducing

young researchers into research networks with given

interests and practices. The distant tutor provides

them with another set of skills – e.g. epistemological,

methodological, strategical, communication

toolboxes. Confronting and complementing what

both kind of tutors provide in a constructive and

critical perspective should help to educate an open

generation of researchers. This not to mention peer

tutoring or collaborative learning and the source of

richness that each individual represents in such an

international learning and teaching environment.

Interactions lead to discussions, which in turn lead to

potential questioning of each other’s practices and

potential redefinition of new common ways.

3 MODEL SUGGESTED

To train PhD students, and building on this

conceptual framework, the model we suggest is

fivefold.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

490

From a pedagogical point of view, young

researchers should be able to learn both from their

own research project and from their participation in

real research projects with a role of novice

researchers (Class, Schneider, & Al, 2017; Ross &

Call-Cummings, 2020). The latter should enable them

to establish a critical and productive distance with the

project and research processes by being accountable

for only a small share. Regarding competences,

young researchers should be able to choose courses

that fits their needs or their potential to learn and that

are aligned with their existing competences. To do so,

they must demonstrate autonomous self-evaluation

skills and be prepared to act in a learning

environment ruled by principles of heutagogy

(Blaschke & Hase, 2015). To help them in this

endeavour, competence frameworks could guide

them. For the time being, the one specifically aimed

at young researchers in education (Van der Maren et

al., 2019) or the one for digital skills (Groupe-de-

recherche-interuniversitaire-sur-l’intégration-

pédagogique-des-technologies, 2019) represent a first

step.

Technologically speaking, the open learning

environment should offer all components of open

education – from open admission to open credentials

–, backed with robust infrastructure like blockchain.

It should also enable scientific virtual mobility with

support for language issues. In addition, it should be

forward looking, i.e. integrating supportive artificial

intelligence features concerning research, data

processing for instance.

Tutoring wise, local and contextual support

should be thoughtfully articulated with international

tutoring. This tutoring design transposes the dual

model of Swiss vocational training (Wettstein,

Schmid, & Gonon, 2017) while also taking it a step

further. Local tutoring is needed because of

contextual challenges that can best be tackled by local

experts. International expertise can help to address

remaining issues (e.g. methodological, strategical,

communication) and offer support in a cognitive

apprenticeship approach for instance (Collins &

Kapur, 2014). This form of dual tutoring could

contribute to educating a generation of “intelligently

internationalised researchers” (de Gayardon, 2019).

In terms of a viable economic model for open

education, it has not been found yet but may rest on a

sharing economy perspective (Schor & Cansoy,

2019). Assets available and possibly not used to their

full potential are various. In terms of human

resources, tutoring among PhD students at different

advancement stages is not common practice. In the

perspective of social learning, setting up pools of PhD

students organised according to communities of

practice, in turn organised in landscapes, could

represent a way forward (Wenger-Trayner, Fenton-

O'Creevy, Hutchinson, Kubiak, & Wenger-Trayner,

2015). Networking approaches (Goodyear, 2019) for

research education could contribute to the building of

a common scientific ground (Dillenbourg & Traum,

2006) in the reality of open education practices

(Cronin, 2017). Developing open technological

environments that support researchers represent

another avenue. We think for instance of electronic

laboratory notebook systems with integrated data

processing and blended with social features. Of

course, these environments should comply with legal

regulations in terms of data protection.

This consideration leads us to the last dimension

of our model, namely institutional policies and

international regulations. These should support both

avenues currently under investigation within the

domain of open education. First, they should

empower individuals and/or groups within existing

structures. Second, they should transform existing

structures in order to achieve equity (Cronin, 2019,

2020) and a form of epistemic justice (Kidd, Medina,

& Pohlhaus, 2017).

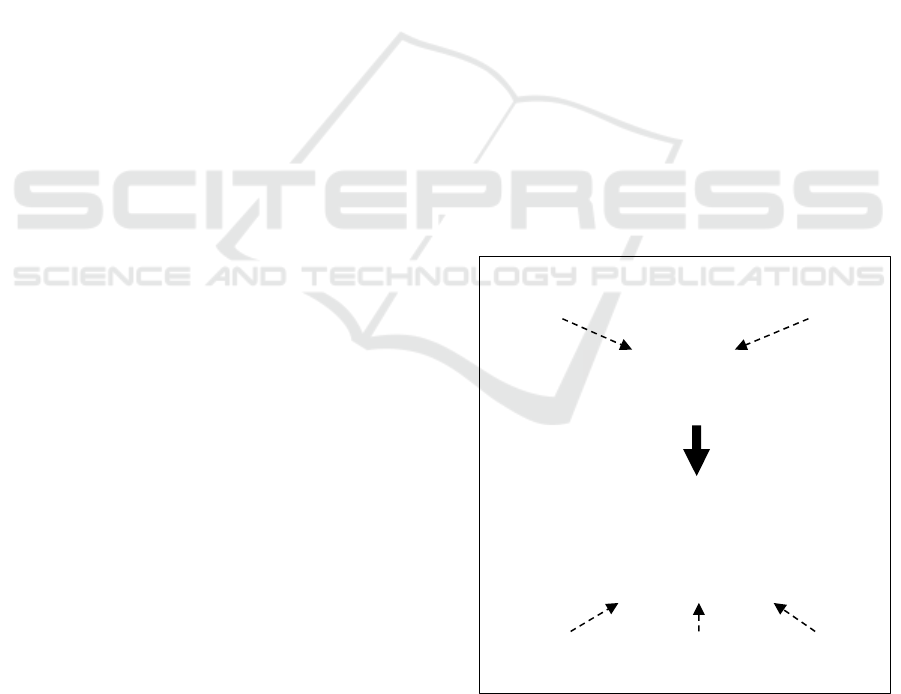

To synthesise (Figure 1), our model for an

international learning environment in research

education addresses pedagogical and technological

issues and is articulated to viable and fair, economic

and institutional surroundings.

Figure 1: Visual representation of the initial model for an

international learning environment in research education.

Institutional

p

olicies

Economic

model

Pedagogy

Technology

Dual tutoring

Empower individual and groups

Achieve epistemic justice

Sustainability - equity

Social learning approaches

“Intelligently internationalised researcher” education (e.g. well-

trained, responsible, engaged, critical-thinker, ownership)

Open education infrastructure for robust, highly trustable

environments

Dual tutoring: respectful of contexts and international

support

Features for an International Learning Environment in Research Education

491

4 TO CONCLUDE

Infrastructure wise, collapse and/or ICT for

development computing may show sustainable ways

forward (Tomlinson, Silberman, Patterson, Pan, &

Blevis, 2012).

We interpret sustainable development goal 4,

which is about “ensur[ing] inclusive and equitable

quality education and promot[ing] lifelong learning

opportunities for all” (UnitedNations, 2019), broadly.

We believe that young researchers, by integrating

international networks, will be better equipped to

address educational challenges of our present and

future. Early integration in international research

communities and early acquaintance with

international research method standards should be

globally beneficial. The confrontation with new

challenges should boost collaborative, creative and

sustainable solutions that should in turn be beneficial

for education in a globalised world. Early integration

of international scientific networks should also be

beneficial to advance the difficult question of

research funding (Beaudry, Mouton, & Prozesky,

2018; Currie-Alder, Arvanitis, & Hanafi, 2018).

Finally, we believe that this model could

contribute to setting up an open learning and teaching

environment in which actors would be aware of their

worldwide inter-connectedness, responsible, engaged

and could exercise agency.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This position paper takes place at the very start of an

SNF funded project entitled Open Education for

Research Methodology Teaching across the

Mediterranean.

REFERENCES

Anderberg, A., Andonova, E., Bellia, M., Calès, L.,

Inamorato Dos Santos, A., Kounelis, I., . . . Spirito, L.

(2019). Blockchain Now And Tomorrow (S. Figueiredo

Do Nascimento & A. Roque Mendes Polvora Eds.).

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European

Union.

Attia, M., & Edge, J. (2017). Be(com)ing a reflexive

researcher: a developmental approach to research

methodology. Open Review of Educational Research,

4(1), 33-45. doi:10.1080/23265507.2017.1300068

Bachmann, H. (2018). Competence-oriented teaching and

learning in higher education - Essentials. Bern: HEP

Verlag.

Barnard, S., Mallaband, B., & Leder Mackley, K. (2019).

Enhancing skills of academic researchers: The

development of a participatory threefold peer learning

model. Innovations in Education and Teaching

International, 56(2), 173-183. doi:10.1080/

14703297.2018.1505538

Beaudry, C., Mouton, J., & Prozesky, H. (Eds.). (2018). The

next generation of scientists in Africa. South Africa:

African Minds.

Blaschke, L. M., & Hase, S. (2015). Heutagogy,

Technology, and Lifelong Learning for Professional

and Part-Time Learners. In A. Dailey-Hebert & K. S.

Dennis (Eds.), Transformative Perspectives and

Processes in Higher Education (pp. 75-94). Cham:

Springer International Publishing.

Boekholt, P., Edler, J., Cunningham, P., & Flanagan, K.

(2009). Drivers of International Collaboration in

Research. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/

research/iscp/pdf/publications/drivers_sti.pdf

Bridges, D. (2017). Philosophy in Educational Research:

Epistemology, Ethics, Politics and Quality. Cham:

Springer International Publishing.

Buchem, I., Konert, J., Carlino, C., Casanova, G.,

Rajagopal, K., Firssova, O., & Andone, D. (2018).

Designing a Collaborative Learning Hub for Virtual

Mobility Skills - Insights from the European Project

Open Virtual Mobility. In Z. P & I. A (Eds.), Learning

and Collaboration Technologies. Design, Development

and Technological Innovation. LCT 2018. Lecture

Notes in Computer Science, vol 10924 (pp. 350-375).

Cham: Springer.

Class, B. (2009). A blended socio-constructivist course with

an activity-based, collaborative learning environment

intended for trainers of conference interpreters. (PhD),

Université de Genève, Geneva. (420). doi:10.13097/

archive-ouverte/unige:4780

Class, B. (2019). More than à la carte international research

methodology courses: towards researching

professionals and professional researchers? The

RESET-Francophone project. In J. Theo Bastiaens

(Ed.), EdMedia + Innovate Learning (pp. 811-816).

Amsterdam, Netherlands: Association for the

Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Class, B., Schneider, D., & Al. (2017). Pistes réflexives sur

l’apprentissage de la méthodologie de la recherche en

technologie éducative. Frantice.net, Numéro spécial

12-13, 149-174.

Collins, A., & Kapur, M. (2014). Cognitive Apprenticeship.

In R. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of the

Learning Sciences

(pp. 109-127). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press. .

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and Praxis: Exploring the Use

of Open Educational Practices in Higher Education.

International Review of Research in Open and

Distributed Learning, 18(5), 15-34. doi:https://doi.org/

10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

Cronin, C. (2019). Open education: Design and policy

considerations. In H. Beetham & R. Sharpe (Eds.),

Rethinking pedagogy for digital age: Principles and

practices of design (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

492

Cronin, C. (2020). Open education: Walking a critical path.

In D. Conrad & P. Prinsloo (Eds.), Open(ing)

education: Theory and practice. Leiden and Boston:

Brill.

Currie-Alder, B., Arvanitis, R., & Hanafi, S. (2018).

Research in Arabic-speaking countries: Funding

competitions, international collaboration, and career

incentives. Science and Public Policy, 45(1), 74-82.

doi:10.1093/scipol/scx048

Dawson, C. (2016). 100 Activities for Teaching Research

Methods. London: Sage.

de Gayardon, A. (2019). The Intelligently Internationalized

Researcher. In K. A. Godwin & H. De Wit (Eds.),

Intelligent Internationalization. The Shape of Things to

Come (pp. 51-55). Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Deardorff, D., de Wit, H., Heyl, J., & Adams, T. (2012).

The SAGE Handbook of International Higher

Education. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Dillenbourg, P., & Traum, D. (2006). Sharing solutions:

persistence and grounding in multi-modal collaborative

problem solving. The Journal of the Learning Sciences,

15(1), 121-151.

Döbeli, B., Hielscher, M., & Hartmann, W. (2018).

Lehrmittel in einer digitalen Welt. Expertenbericht im

Auftrag der Interkantonalen Lehrmittelzentrale (ilz).

Retrieved from http://www.ilz.ch/bericht/

Earley, M. (2014). A synthesis of the literature on research

methods education. Teaching in Higher Education,

19(3), 242-253. doi:10.1080/13562517.2013.860105

Gaillard, J., & Bouabid, H. (2017). La recherche

scientifique au Maroc et son internationalisation.

Saarbrucken: Editions universitaires européennes

Goodyear, P. (2019). Networked Professional Learning,

Design Research and Social Innovation. In A.

Littlejohn, J. Jaldemark, E. Vrieling-Teunter, & F.

Nijland (Eds.), Networked Professional Learning.

Emerging and Equitable Discourses for Professional

Development (pp. 239-256). Cham: Springer.

Grech, A., & Camilleri, A. (2017). Blockchain in Education

(A. Inamorato dos Santos Ed.). Luxembourg:

Publications Office of the European Union.

Groupe-de-recherche-interuniversitaire-sur-l’intégration-

pédagogique-des-technologies. (2019). Cadre de

référence de la compétence numérique. Retrieved from

http://recit.qc.ca/nouvelle/cadre-de-reference-de-la-

competence-numerique/

Halbherr, T., & Kapur, M. (2019). Validity and Resource

Affordances in Examinations: A Theoretical and

Methodological Framework.

Hart, R. (1992). Children's Participation: From tokenism to

citizenship. Retrieved from Florence, Italy:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24139916_C

hildren%27s_Participation_From_Tokenism_To_Citiz

enship

Huisman, J., Adelman, C., Hsieh, C., Shams, F., & Wilkins,

S. (2012). Europe's Bologna process and its impact on

global higher education In D. K. Deardorff, H. D. Wit,

& J. D. Heyl (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of

International Higher Education (pp. 81-100).

Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

John, L. K., Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (2012).

Measuring the Prevalence of Questionable Research

Practices With Incentives for Truth Telling.

Psychological Science, 23(5), 524-532.

doi:10.1177/0956797611430953

Kidd, I., Medina, J., & Pohlhaus, G. (Eds.). (2017). The

Routledge Handbook of Epistemic Injustice. New York:

Routledge.

Kilburn, D., Nind, M., & Wiles, R. (2014). Learning as

Researchers and Teachers: The Development of a

Pedagogical Culture for Social Science Research

Methods? British Journal of Educational Studies,

62(2), 191-207. doi:10.1080/00071005.2014.918576

Lewthwaite, S., & Nind, M. (2016). Teaching Research

Methods in the Social Sciences: Expert Perspectives on

Pedagogy and Practice. British Journal of Educational

Studies in Continuing Education, 64(4), 413-430.

doi:10.1080/00071005.2016.1197882

Müller, P. (2020). Blockchain for Education.

Nascimbeni, F., Burgos, D., Aceto, S., Wimpenny, K.,

Maya, I., Stefanelli, C., & Eldeib, A. (2018). Exploring

intercultural learning through a blended course about

open education practices across the Mediterranean. In

IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference:

Emerging Trends and Challenges of Engineering

Education, EDUCON.

Nicholas, D., Watkinson, A., Boukacem-Zeghmouri, C.,

Rodríguez-Bravo, B., Xu, J., Abrizah, A., . . . Herman,

E. (2017). Early career researchers: Scholarly

behaviour and the prospect of change. Learned

Publishing, 30(2), 157-166. doi:10.1002/leap.1098

Nind, M., & Lewthwaite, S. (2018). Hard to teach: inclusive

pedagogy in social science research methods education.

International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(1), 74-

88. doi:10.1080/13603116.2017.1355413

Nind, M., & Lewthwaite, S. (2018). Methods that teach:

developing pedagogic research methods, developing

pedagogy. International Journal of Research & Method

in Education and Information Technologies.

doi:10.1080/1743727X.2018.1427057

Nind, M., & Lewthwaite, S. (2019). A conceptual-empirical

typology of social science research methods pedagogy.

Research Papers in Education, 1-21.

doi:10.1080/02671522.2019.1601756

Peters, R. S. (1966). Ethics and Education (Routledge

Revivals). London Routledge.

Ross, K., & Call-Cummings, M. (2020). Reflections on

failure: teaching research methodology. International

Journal of Research & Method in Education, 1-14.

doi:10.1080/1743727X.2020.1719060

Schor, J., & Cansoy, M. (2019). The Sharing Economy. In

F. Wherry & I. Woodward (Eds.), The Oxford

Handbook of Consumption. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Tomlinson, B., Silberman, S., Patterson, D., Pan, Y., &

Blevis, E. (2012). Collapse informatics: augmenting the

sustainability & ICT4D discourse in HCI. In SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems

(pp. 655-664). Austin Texas USA: Association for

Computing Machinery.

Features for an International Learning Environment in Research Education

493

UNESCO, C. (2019). Guidelines on the development of

open educational resources policies. Retrieved from

Paris & Burnaby: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/

48223/pf0000371129

UnitedNations. (2019). Special edition: progress towards

the Sustainable Development Goals. Report of the

Secretary-General. Retrieved from https://undocs.org/

E/2019/68

Van der Maren, J.-M., Brodeur, M., Gervais, F., Gilles, J.-

L., & Voz, G. (2019). Référentiel pour la formation des

chercheuses et des chercheurs francophones en

éducation. Document adopté par l’Association des

doyens, doyennes et directeurs, directrices pour l'étude

et la recherche en éducation au Québec (ADEREQ),

Montréal: ADEREQ.

Villar-Onrubia, D., & Rajpal, B. (2016). Online

international learning. Perspectives: Policy and

Practice in Higher Education, 20(2-3), 75-82.

doi:10.1080/13603108.2015.1067652

Waast, R., & Gaillard, J. (2018). L’Afrique: Entre sciences

nationales et marché international du travail

scientifique. In M. Kleiche-Dray (Ed.), Les ancrages

nationaux de la science mondiale - XVIIIe-XXIe siècle

(pp. 67-98). Paris: IRD Éditions/Éditions des archives

contemporaines

Wagner, C., Garner, M., & Kawulich, B. (2011). The state

of the art of teaching research methods in the social

sciences: towards a pedagogical culture. Studies in

Higher Education, 36(1).

Wenger-Trayner, Fenton-O'Creevy, M., Hutchinson, S.,

Kubiak, C., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Learning in

Landscapes of Practice. Boundaries, identity, and

knowledgeability in practice-based learning. London:

Routledge.

Wettstein, E., Schmid, E., & Gonon, P. (2017). Swiss

Vocational and Professional Education and Training

(VPET). Forms, System, Stakeholders. Bern: hep.

Wiley, D. (2017). Iterating Toward Openness: Lessons

Learned on a Personal Journey. In R. S. Jhangiani & R.

Biswas-Diener (Eds.), Open: The Philosophy and

Practices that are Revolutionizing Education and

Science. London: Ubiquity Press.

Wiley, D., Bliss, T., & McEwen, M. (2014). Open

Educational Resources: A Review of the Literature. In

J. Spector, M. Merrill, J. Elen, & M. Bishop (Eds.),

Handbook of Research on Educational

Communications and Technology (pp. 781-789). New

York: Springer.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

494