Reading Fluency Training with Amazon Alexa

Sara Durski

1a

, Wolfgang Müller

1b

, Sandra Rebholz

1c

and Ute Massler

2

1

Media Education, University of Education Weingarten, Kirchplatz 2, 88250 Weingarten, Germany

2

English Department, University of Education Weingarten, Kirchplatz 2, 88250 Weingarten, Germany

Keywords: Amazon Alexa, Reader’s Theatre, Reading Fluency, Smart Speaker, Speech Technologies,

Technology-Enhanced Learning.

Abstract: This paper presents the conception, development and evaluation of an Amazon Alexa application (Skill) for

the training of reading fluency. This Skill takes on different roles in a multilingual Reader’s Theatre, a reading

out loud method to train reading fluency. In this approach, children may choose and practice one or more

roles in a script by reading out loud their dialogues with the reading partner Amazon Alexa. The student and

Alexa take turns in reading. Alexa gives feedback to the student, acts as a reading model, and has the role of

a cooperative reading partner. In an iterative process, the development of the prototype was continuously

evaluated and adapted. The Skill was evaluated with three students who tried out the Skill and were

interviewed about the acceptance, the fun factor and their future use. The evaluation focused on the

functionality and usability of a possible technical implementation. Despite various technical limitations, a

final evaluation showed that the Skill can be suitable as a co-partner for a Reader’s Theatre.

1 INTRODUCTION

Digitalization has advanced mobile devices such as

tablets or smartphones to an indispensable part of our

private and professional lives. 98% of German

households today own mobile devices, and 97% of

them have Internet access (Feierabend, Plankenhorn

& Rathgeb, 2016), which means that Children and

teenagers come into contact with digital media

starting from a very young age. Smart speakers, such

as Amazon Alexa, are increasingly a part of today’s

family lives. A total of 86.2 million smart speakers

were sold in 2018. During the fourth quarter of 2018

there were more smart speakers sold worldwide than

in the entire year of 2017. (Strategy Analytics, 2018).

One of the most popular smart speakers is Amazon’s

Alexa, a device used in many fields, such as Utilities,

Health & Fitness, News, Kids, Communication,

Smart Home, and Education (Amazon.com, Inc. & its

affiliates, 1998-2019). With the progressive

development of technological innovation, digitization

offers new possibilities for the use of media in the

context of teaching and learning. Alexa's interaction

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0744-7983

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6474-3733

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0965-998X

features, her lively voice and the Amazon’s

personalized programming possibilities, offer great

potential in educational contexts. In this project, we

investigated to what extent smart speakers are

suitable as reading partners for students as a means to

improve their reading abilities.

2 PROBLEM, APPROACH AND

OBJECTIVES

A significant deficit in reading competence is a

phenomenon observable not only in countries with

less developed educational systems, but also among

students in primary and secondary level school in

many first-world countries (OECD, 2015). Such

inadequate reading competence may not only impair

the learning of other school subjects, it may also

negatively impact the future and professional life of

such students (Grabe, 20009; Grotlüschen &

Riekmann, 2011). Reading fluency is considered a

fundamental basis for higher reading competence

(Grabe, 20009). Hence, students should be able to

Durski, S., Müller, W., Rebholz, S. and Massler, U.

Reading Fluency Training with Amazon Alexa.

DOI: 10.5220/0009568201390146

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 2, pages 139-146

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

139

assign word meanings reliably and quickly at the

level of letters, words, sentences, and text passages.

In addition, texts should be read at a certain speed and

with the right intonation. Repeated reading aloud may

improve accuracy, fluency and understanding of

reading (NICHD, 2000). There are a number of

instructional approaches linked to reading aloud, such

as the Reader’s Theatre method (Nix, 2006).

However, all of these methods require a reading

partner and intensive practice to improve reading

competence. Finding an adequate reading partner

outside of class is often a problem due to a number of

reasons. For example, if a student’s family has a

migration background, parents frequently lack the

required language skills to assist their children, or if

family members are unavailable due to their work

schedules.

In this paper, an approach aimed at addressing this

problem by means of commercial speech technology,

namely Amazon Alexa, is presented and evaluated.

The contribution of this paper is first, the presentation

of novel technology-based, self-directed learning

activities that integrate (commercial) language

technologies, and smart speakers. And second, this

paper provides an evaluation of Amazon Alexa’s

ability to provide sufficient quality when applied in

such scenarios. Furthermore, first results with respect

to the acceptance of such technology by learners are

presented.

3 STATE OF THE ART

This work focuses on the conception, implementation

and evaluation of digital learning media for the

method of multilingual Reader’s Theatre (MELT)

(Kutzelmann, Massler, Klaus, Götz & Ilg, 2017). The

MELT method is based on the Reader’s Theatre

approach (Nix, 2006) which integrates repeated

reading aloud in order to increase reading ability

(Rosebrock, Nix, Rickmann & Gold, 2011). In the

Reader’s Theatre, students practice a performance

linked to reading texts, which in turn develops their

reading fluency “on the side”. Students train

cooperative dialogical texts, which are divided into

speaker and narrator roles (Mraz et al., 2013). The

multilingual Reader’s Theatre is an extension of the

Reader’s Theatre taking a bilingual or multilingual

approach. In this approach, scripts may integrate not

only the national language and foreign languages, but

also migration languages. Students not only practice

their reading fluency in cooperative groups, they also

engage in self-learning phases. Studies have

confirmed that learners and teachers value the

multilingual Reader’s Theatre as very motivating and

instructive (Kutzelmann et al., 2017).

For more than three decades, the use of computers for

learning has been investigated. Much of the early

research has focused on the potential of training

programs to make better and faster learning possible.

Computers have the unique ability of offering

individualized practice to students who need to

improve their reading fluency. Moreover, computers

have proven beneficial in developing the ability to

decode. (Hasselbring & Goin, 2004). In the digital

domain, there is already a multitude of learning

software geared to improving text comprehension

skills, practicing reading fluency in the mother

language or in foreign languages, and training

vocabulary.

Parr (2008) developed an approach to using text-

to-speech technology that offers the possibility to

read out words, sentences and texts fluidly with a

computer-generated voice. This technology gives

students with reading difficulties the chance to work

independently in accordance with class level

expectations (Hasselbring & Bausch, 2005/2006).

Students are supported in decoding and word

identification thus allowing students with limited

reading ability to read longer texts (Parr, 2008).

Digital technologies are not only useful as a reading

model, but also as an application that listens to

students read and then give feedback on their

performance. For example, the digital application

MyTurnToRead is designed as a virtual reading

partner to practice reading fluency (Madnani et al.,

2019). Based on an e-book, MyTurnToRead

demonstrates how a virtual reading partner is useful

for developing reading fluency. With this application,

the student and virtual partner take turns reading

aloud. The student can follow along while the virtual

partner reads aloud. By highlighting the sentence that

is being read aloud, the student’s focus is maintained.

At any time, the student may pause the digital reading

out or repeat a part that has already been read aloud.

In addition, students have the possibility to record

themselves while reading aloud text and then listen to

it afterwards. After reading, the student engages in

comprehension tasks.

The reading tutor, a computer-based tool, with

speech recognition (Bernstein & Cheng, 2008) was

developed specifically to help students practice their

reading skills. The reading tutor has been shown to

improve not only the reading skills of native English

speaking students (Mostow et al., 2008), but also

students of English as a Second Language (ESL)

(Poulsen, Wiemer-Hastings & Allbritton, 2007). The

reading tutor displays stories on a screen and records

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

140

the student while reading aloud. By means of speech

recognition and automatic text analysis, the reading

tutor can give feedback on the student’s performance

(Mostow & Aist, 2001).

The Peabody Literacy Lab (PLL), a tutoring

system designed for secondary school students, relies

on a unique combination of learning theory,

pedagogical principles and integrated media

technologies (Hasselbring & Goin, 2004). This

program teaches word recognition, decoding, spelling

and text comprehension. An animated tutor guides the

student through the instructional units and provides

feedback of the student’s performance via a digitized

human voice. The program tracks individual student

progress and adapts the lessons accordingly.

As stated above, one means for developing

reading skills is the Reader’s Theatre where students

practice reading aloud. To accommodate recent

technological advancement, the Reader’s Theatre has

been expanded to include digital media. However,

these are not digital reading partners, rather

extensions to the design of the final performance. In

the following, two examples are presented for how

digital media can be integrated into the Reader’s

Theatre method.

Vasinda and McLeod (2011) have expanded the

traditional Reader’s Theatre by using podcasts. In the

process, podcast recordings of the performances were

made and published. By publishing a podcast

recording of the theatre performance, parents unable

to attend their child’s performance, could listen to the

reading. Story Reading Environmental Enrichment

(STREEN), an innovative space for reading stories at

primary school age, is another example for

integrating digital media into the Reader’s Theatre

method. Depending on the reading performance and

story, it uses technical infrastructure in the form of an

augmented e-book. STREEN has been shown to

elevate the reader’s motivation by changing the space

in which they read. STREEN is an artificial

environment in which technical infrastructure can

trigger technical media additions based on reading

performance and story. (Ribeiro, Iurgel, Müller &

Ressel, 2016). Speech recognition and eye tracking

technologies are used to detect events in a reading

aloud scenario, or a quiet reading scenario,

respectively. Smart speakers such as Amazon Alexa

are enablers for combining text-to-speech

technology, personalized reading feedback and

reading loud out method.

In this project, existing technologies of smart

speakers were used and adapted to the context of

reading fluency training. The most popular smart

speakers are products offered by Apple (Siri), Google

(Google Assistant), Microsoft (Cortana), Samsung

(Bixby) and Amazon (Alexa) (Drewer, Massion &

Pulitano, 2017). The advantage of Amazon Alexa has

is for third parties to develop and deploy custom

Skills, i.e. software components for extending the

assistant with additional voice commands. The voice

command 'Alexa' connects Alexa or the Amazon

Echo device synchronously with the remote Amazon

Voice Service, thus allowing access to the custom

Skill. By doing so, all additional voice commands

become available to the end user. Using them invokes

the corresponding action in the customised Alexa

Skill (Amazon.com, Inc. & its affiliates, 2010-2019a).

The number of custom Amazon Alexa Skills in the

USA more than doubled in 2018. At the beginning of

2018, there were 25,784 Amazon Alexa Skills in the

USA. By the beginning of 2019, there were already

56,750 Skills. This constant increase demonstrates the

continuing interest of developers in the Amazon

Alexa technology. It is not only the end users who

benefit from this growth, but also Amazon. It shows

the engagement of the developers, who are of crucial

importance for increasing the value of this platform

(Kinsella, 2019). Echo Show provides additional

interaction possibilities through a touch display.

4 METHODOLOGY:

DESIGN-BASED RESEARCH

The objective of our project was to determine the

potentials and limitations of Amazon Alexa as an

electronic learning tool in the form of a training

partner for MELT. The focus of this study was on

technological feasibility and acceptance. The

following research question is: To what extent is

Amazon Alexa suitable as a reading partner for

training reading fluency? The project pursued a

Design-Based Research (DBR) approach, combining

knowledge- and application-oriented research in a

continuous cycle of design, implementation,

evaluation and re-design (Design-Based Research

Collective, 2003). In addition, methods and

instruments of User Experience (UX) design and

usability engineering (DIN EN ISO 9241-210, 2010)

were used. Users were integrated into the product

development process at an early stage. They engaged

in the study by regularly testing the usability of the

product with usability tests during implementation.

Reading Fluency Training with Amazon Alexa

141

5 CONCEPT

The target group in need of reading support were the

end of primary school students and early secondary

school students with reading fluency deficiencies.

The following objectives were pursued:

• supplementing the Reader’s Theatre with self-

study sessions at home;

• training the reading of selected roles in a dialog;

• implementing Amazon Alexa as a reading

partner;

The advantage of combining MELT with Amazon

Alexa is that she can be used as a co-partner for

reading all of the other theatre roles. In addition,

Alexa is able to pronounce and properly emphasize

words and sentences. In this way, Alexa serves as a

speech model. By using Alexa Echo Show, the

display can be used to read the texts. Another

advantage is students may also receive feedback

concerning errors they make while reading aloud. At

the end of the training session, students receive a

numerical score based on the errors they make while

reading aloud.

Personas and scenarios were created early in the

project. The following scenario illustrates the

intended use which starts with Miranda coming home

from school. That day, her English teacher introduced

the reading aloud method MELT in her lessons and

plans a joint reading performance at the end of the

week. Since in her first attempt Miranda did not

perform well when reading her role, she would like to

practice at home However, she lacks an appropriate

reading partner. Fortunately, her family owns an

Alexa Show, and her teacher has already provided her

with the necessary Skill enhancements, which her

father had installed the previous day. She starts her

activity with Alexa. Now she is able to read the text

and concentrate on her role, while Alexa takes over

the roles of her classmates. Whenever she makes an

error, Alexa provides feedback.

The concept of this work includes the

implementation of a reading text with different

reading roles. The student has the opportunity to

select each role to read with Alexa. The developed

Skill can be used with an Amazon Echo device, or a

mobile device with the Amazon Alexa App. By using

the Echo Show the functionality can be extended so

that it shows images and texts on the display, and use

of a touch interaction function. The difficulty level of

the reading text was adapted to the target group. After

the training sessions, the students receive score for

their reading performance.

6 IMPLEMENTATION

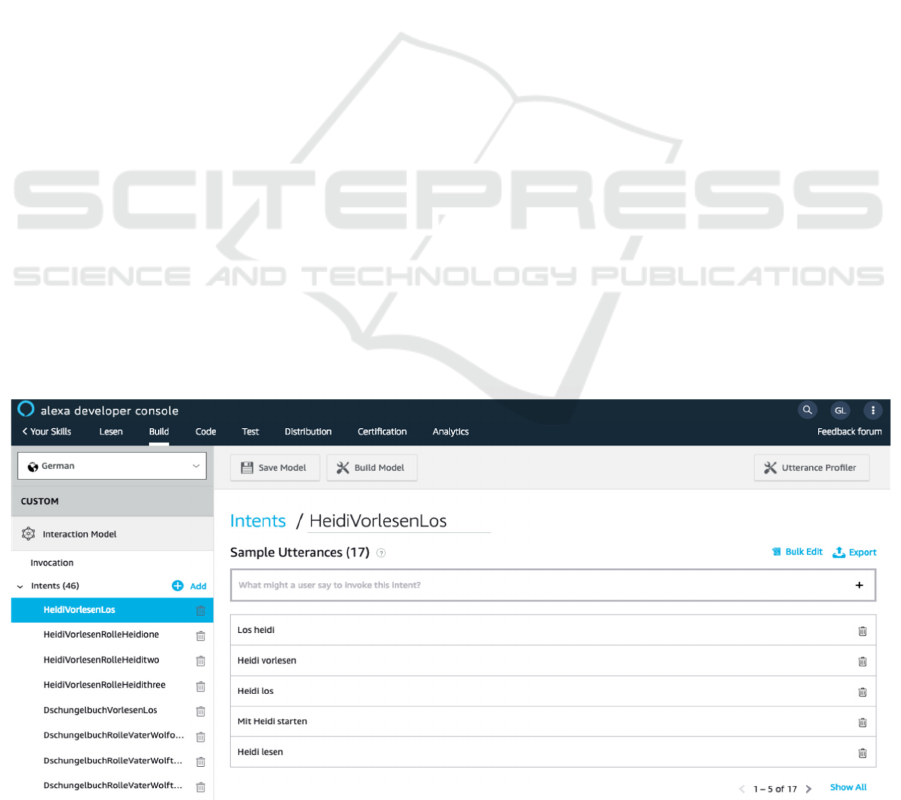

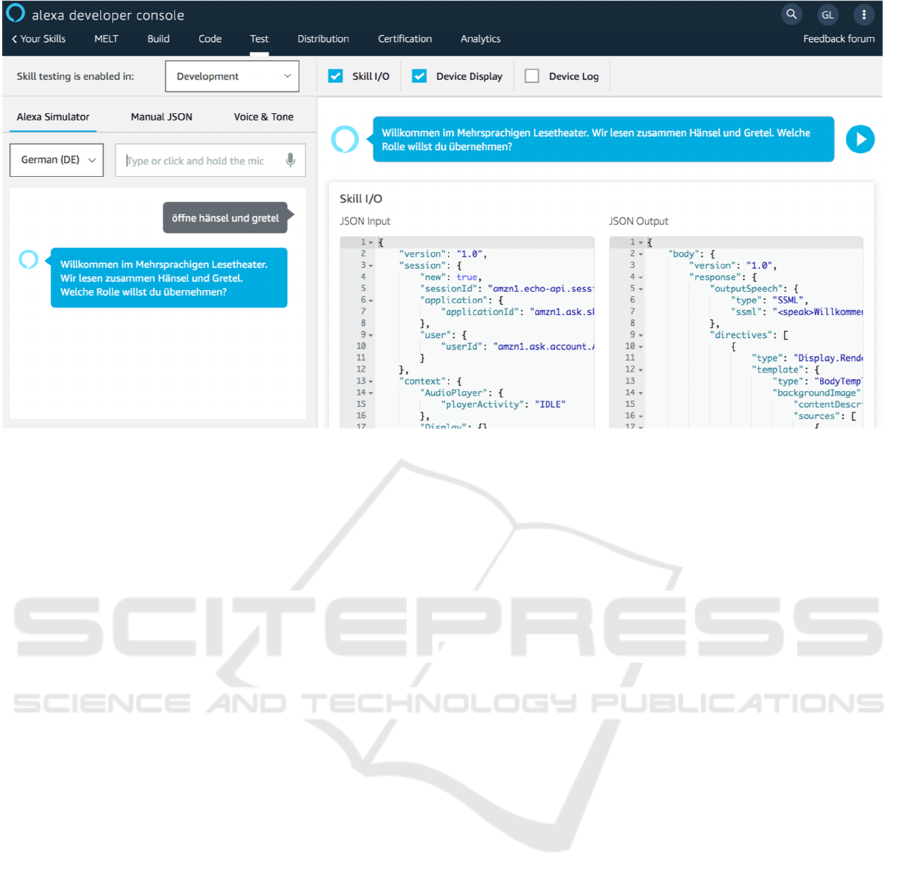

A prototype for the custom Alexa-Skill was

developed. The Skill was programmed into the

Amazon Developer Console and the AWS Lambda

Management Console (Amazon.com, Inc. & its

affiliates, 2010-2019b). The development of the Skill

can be organized in the Amazon Developer Console.

The Skill can be tested without an additional Amazon

Echo device (Figure 1 and 2). In this console the Skill

name is defined. Then, a user-defined interaction

model containing the logic of the app and voice inter-

face needed to interact with Alexa are created and

configured.

Figure 1: Amazon Developer Console to organize the Skill.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

142

Figure 2: Amazon Developer Console to test the Skill.

To define the voice interface, the user's voice

input is assigned to so-called intents. This allows the

cloud-based service from Amazon to process the

voice input. The endpoint or the link to the AWS

Lambda Management Console is also entered

(Amazon.com, Inc. & its affiliates, 2010-2019c). A

Node.js function code was written into the console,

which can be executed when an intent is called up by

voice commands. The code example shows the

template code for the Alexa Show Display and the

speech output:

'HeidiVorlesenLos': function () {

if (supportsDisplay.call(this)) {

const bodyTemplate1 = new

Alexa.templateBuilders.BodyTemplate1

Builder();

var template =

bodyTemplate1.setTitle("GameLet

App")

.setTextContent(makePlainText("Es

geht los."))

.build();

speechOutput = "Es geht los.";

this.response.speak(speechOutput);

this.response.renderTemplate(templat

e);

this.response.listen();

this.emit(":responseReady");

}

The following problems and obstacles were

encountered during implementation. First, all intents

are created in the same way and have equal rights,

which means that all of them can be used at any time.

This has the advantage that students can start reading

at any part of the text, at any time. However, the

disadvantage is the possibility that Alexa could begin

reading from a different part of the text if the

command is not clear. Second, Amazon offers only

two or three voices for many of the languages in the

program (Amazon Web Services, Inc. or its affiliates,

2006-2019). Consequently, several roles must be

assigned to the same voices. Third, Alexa Show stops

reading aloud when her display has been touched,

which means no interaction is possible while reading

aloud. The consequence here is the text cannot be

scrolled up. Finally, when changing or re-

implementing stories, obstacles can arise because

they are complex and require programming

knowledge.

7 EVALUATION

The prototype of the Alexa Skill was tested and

evaluated by means of three representative target

group students. Functionality and usability of a

possible technical implementation were the focus of

the study. Technical optimization was derived from

these results. Privacy issues were taken into account

to the extent that no student data are saved. Most

importantly, Alexa is used solely for educational

purposes.

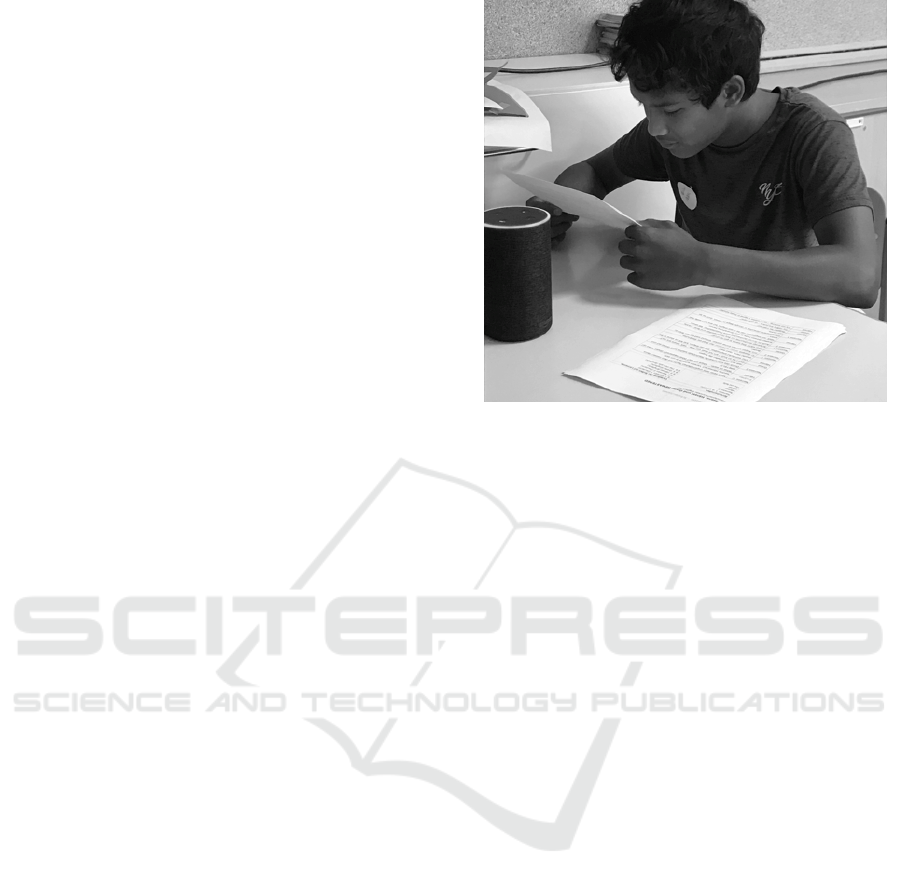

Testing began with a short introduction to MELT

and the Alexa Skill, the students were asked to read

their role in the Reader’s Theatre with Alexa. This

they carried out on their own (Figure 3). After the

students had tried out the Skill, a semi-structured

Reading Fluency Training with Amazon Alexa

143

interview was conducted. In this interview, the

students were asked questions about acceptance, fun

factor and future use. In general, it can be said that all

three students used the Skill intuitively.

The interview results could be organised in the

following five points:

• Alexa's reaction: The students found Alexa's

reaction time and waiting time to be too long.

However, the reaction sensitivity to the read-out

text rarely led to problems.

• Understandability: After a short introduction,

the students were able to use the Skill intuitively.

They quickly understood how the Skill works.

Moreover, orientation was reported to be easy.

• Functionality of Alexa: Sometimes there were

small functional errors, e.g. turning itself off

unexpectedly. Another issue is the student wish for

a larger portion of reading activities in the Reader’s

Theatre. Furthermore, the extension of Alexa by

Echo Show was rated as very positive: "Reading the

text from Alexa Show is much cooler than from

paper."

• Pronunciation: The use of three different

languages in the Skill was confusing for all students

because Alexa can speak any given role with

different voices and in different languages.

Although Alexa is a good speech model for

pronunciation, she cannot correct student

pronunciation errors. For this reason, she is unable

to react to incorrectly modulated sentences,

incorrectly pronounced words, and missing words.

If she has recognized enough words, she just reads

on in the script and may miss some serious errors.

• Fun and acceptance: The students were

enthusiastic about reading with Alexa. In the

interviews, the following statements were noted in

response to the question about willingness to

continue using the Skill for reading practice in the

future: "In a bilingual script I would use the app to

learn English", "Yes, when can I download the app

for Alexa?", "There should be a lot more books in

the app".

Due to clear pronunciation and modulation, Alexa

acts as a good speech model. However, the speech

recognition varies widely, hence affecting reliability

to provide mispronunciation corrections or error

feedback.

Figure 3: Usability Test with Amazon Alexa.

For example, Alexa is not able to distinguish

between pronunciation errors, reading speed or

incorrect modulation. Either the keywords defined in

the Skill match the voice entry and Alexa can continue

reading in the script, or there is no match and Alexa

asks the student to make the voice entry again. This

problem caused confusion among the students. Here,

the Alexa software appears to be the source of the

problem. Although the commands can be used at any

time, making it easier to get started with the Reader’s

Theatre, this option can also cause confusion and

disorientation if Alexa misunderstands the student

hence causing her to switch erratically between

different parts of the text. On the one hand the gaming

character of the built-in error score is an added feature

that is found to motivate the students. On the other

hand, it may also put students under pressure to

perform well. The overall positive student reaction to

Alexa as a reading trainer resulted from the intuitive

functionality and ease in use. The students expressed

their interest in using Alexa to train their reading

skills.

According to the Design-Based Research approach,

the re-designing of the Skill should take place after

further analysis of the evaluation results. The

prototype should be further developed according to

the results of this study.

8 DISCUSSION

Although methods for training reading fluency, such

as MELT, require a reading partner, not every student

has the opportunity to practice reading with a partner

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

144

outside of school lessons. For this reason, a digital

tutor can be useful for reading training. According to

Aist et. al. (2001) a digital tutor has been shown to be

a good alternative for those students who require a

partner. The study of Aist et. al. examined the

learning of vocabulary with the help of oral reading.

Traditional teaching was compared with one-to-one

teaching, both with human tutors and with digital

tutors. The results of this study showed that third

graders who learned with a human and digital tutor

demonstrated equally improved word comprehension

and passage comprehension.

The results of this study further prove that Alexa

can be used for reading practice despite some

deficiencies in the quality of speech recognition.

Moreover, this study has found that students were

better motivated to practice their reading skills in

future with Alexa. These findings align with Madnani

et. al. (2019) interviews of 25 children who used

MyTurnToRead. In that study, the children said they

would be interested in using this digital application in

the future. The research has thus revealed that

students who learn with a tutor, in addition to the

traditional classroom lessons, are more likely to

improve their reading skills significantly. Moreover,

these studies have also demonstrated the overall

student acceptance of digital tutors. The findings in

this research with Smart Speaker Alexa as a digital

tutor has enriched the field with further evidence of

its importance for developing reading skills. While

the study demonstrated some technical limits, it also

revealed opportunities that should be developed in

future studies.

9 SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

In the context of a DBR approach the question was

addressed in which way Amazon Alexa could be used

as a reading assistant in the context of MELT. A

prototype of an Alexa was designed, implemented

and evaluated by iterative tests. The technical

potentials and limits of Alexa as an exercise partner

for MELT were determined. The results are positive

despite various limitations. In specific, our first

evaluation suggests that commercial language

technology could be effectively applied to support

students in self-directed learning scenarios, despite

the clearly existing deficiencies in speech recognition

quality. Furthermore, it appears that the overall

positive usability of the system leads to a high level

of acceptance by the learners. It should be noted that

due to the small number of student participants in this

study, the results are limited. However, further

investigation with a larger number of students is

required, as is a deeper focus on language teaching

methods. In addition, a more detailed analysis of

ethical aspects and privacy issues, such as data

retention, may be required. Although some effects of

digital media has been found to negatively impact

student social interaction, here Alexa should be seen

solely as a supplemental tool for school work and as

a support for learning, and not as an additional social

media diversion. The purpose of Alexa is to aid

students who lack a reading partner at home and who

have a need to practice their Reader’s Theatre texts.

In future, various teaching scenarios could be

developed: for example, the perspective of

collaborative learning. Additional functionalities of

Amazon Alexa in terms of Alexa Show, e.g., the

parallel presentation of word definitions or

translations, carry the potential to enhance the

presented scenarios. However, in order to use Alexa

long-term, the technical infrastructure in the school

would have to be adapted. The students require a

stable Internet connection and access rights to Alexa

Echo devices, or mobile devices. Finally, teachers

require media competence and technical instruction

to ensure its use in the classroom.

REFERENCES

Aist, G., Mostow, J., Tobin, B., Burkhead, P., Corbett, A.,

Cuneo, A., Junker, B. & Sklar, M. B. (2001). Computer-

assisted oral reading helps third graders learn

vocabulary better than a classroom control – about as

well as one-on-one human-assisted oral reading,

Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/

publication/244420809_Computerassisted_oral_readin

g_helps_third_graders_learn_vocabulary_better_than_

a_classroom_control_-_about_as_well_as_one-on-

ne_humanassisted_oral_reading, [Accessed 12 March

2020].

Amazon.com, Inc. & its affiliates (1998-2019). Amazon

Alexa Skills. Available at: https://www.amazon.de/

alexaskills/b/ref=sd_allcat_k_a2s_all?ie=UTF8&node

=10068460031, [Accessed 12 August 2019].

Amazon.com, Inc. & its affiliates (2010-2019a). Alexa

Voice Service. Create Devices with Alexa Built-in that

Customers Can Talk to Directly, Available at:

https://developer.amazon.com/de/alexa-voice-service,

[Accessed 12 August 2019].

Amazon.com, Inc. and its affiliates (2010-2019b). Speech

Synthesis Markup Language (SSML) Reference,

Available at: https://developer.amazon.com/de/docs

/custom-skills/speech-synthesis-markup-language-

ssml-reference.html, [Accessed 12 August 2019].

Amazon.com, Inc. and its affiliates (2010-2019c). Manage

Skills in the Developer Console, Available at:

https://developer.amazon.com/

Reading Fluency Training with Amazon Alexa

145

de/docs/devconsole/about-the-developer-console.html,

[Accessed 12 August 2019].

Amazon Web Services, Inc. or its affiliates (2006-2019).

AWS Lambda Entwicklerhandbuch, Available at:

https://aws.amazon.com/, [Accessed 12 August 2019].

Bernstein, J. & Cheng, J. (2008). Logic and Validation of a

Fully Automatic Spoken English Test. In V. M. Holland

& F. P. Fisher (eds.), The Path of Speech Technologies

in Computer Assisted Language Learning: From

Research Toward Practice, Routledge. New York, pp.

174-194.

Design-Based Research Collective (2003). Design-Based-

Research: An Emerging Paradigm for Educational

Inquiry. Educational Researcher, 32/1, pp. 5-8, 2003.

DIN EN ISO 9241-210 (2010). Ergonomics of human-

system interaction — Part 210: Human-centred design

for interactive systems, Available at: https://

www.iso.org/standard/77520.html, [Accessed 12

August 2019].

Drewer, P., Massion, F. & Pulitano, D. (2017). Was haben

Wissensmodellierung, Wissensstrukturierung,

künstliche Intelligenz und Terminologie miteinander zu

tun? Deutsches Institut für Terminologie.

Feierabend, S., Plankenhorn, T. & Rathgeb, T. (2017).

KIM-Studie 2016: Kindheit, Internet, Medien.

Basisstudie zum Medienumgang 6- bis 13-Jähriger in

Deutschland. Medienpädagogischer

Forschungsverbund Südwest, Stuttgart.

Grabe, W. (2009). Reading in a second language: Moving

from Theory to Practice. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Grotlüschen, A. & Riekmann, W. (2011). leo. - Level-One

Studie: Literalität von Erwachsenen auf den unteren

Kompetenzniveaus. Available at: https://blogs.epb.uni-

hamburg.de/leo/files/2011/12/leo-

Presseheft_15_12_2011.pdf, [Accessed 12 August

2019].

Hasselbring, T. S. & Bausch, M. E. (2005/2006). Assistive

technology for reading: Text reader programs, word-

prediction software, and other aids empower youth with

learning disabilities. Education Leadership, 63(4), 72–

75.

Hasselbring, T. S. & Goin, L. I. (2004). Literacy instruction

for older struggling readers: What is the role of

technology? Reading & Writing Quarterly, 20(2), 123–

144.

Kinsella, B. (2019). Amazon Alexa Skill Counts Rise

Rapidly in the U.S., U.K., Germany, France, Japan,

Canada, and Australia. Available at:

https://voicebot.ai/2019/01/02/amazon-alexa-skill-

counts-rise-rapidly-in-the-u-su-k-germany-france-

japan-canada-and-australia/, [Accessed 12 August

2019].

Kutzelmann, S., Massler, U., Klaus, P., Götz, K. & Ilg, A.

(2017). Mehrsprachiges Lesetheater. Handbuch zu

Theorie und Praxis. Leverkusen/Opladen: Budrich.

Madnani, N., Beigman Klebanov, B., Loukina, A.,

Gyawali, B., Sabatini, J., Lange, P. & Flor, M. (2019).

My Turn to Read: An Interleaved E-book Reading Tool

for Developing and Struggling Readers, Available at:

https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P19-3024.pdf,

[Accessed 12 March 2020].

Mostow, J. & Aist, G. (2001). Evaluating Tutors that

Listen: An Overview of Project Listen. In K. D. Rofbus

& P. J. Feltovich (eds.), Smart Machines in Education,

AAAI Press. Cambridge, pp. 169-234.

Mostow, J., Aist, G., Huang, C., Junker, B., Kennedy, R.,

Lan, H., Latimer, D., O’Connor, R., Tassone, R., Tobin,

B. & Wierman, A. (2008). 4-Month Evaluation of a

Learner-Controlled Reading Tutor That Listens. In V.

M. Holland & F. P. Fisher (eds.), The Path of Speech

Technologies in Computer Assisted Language

Learning: From Research Toward Practice, Routledge.

New York, pp. 201-219.

Mraz, M., Nichols, W., Caldwell, S., Beisley, R., Sargent,

S. & Rupley, W. (2013). Improving oral reading

fluency through reader’s theatre. In: Reading Horizons

52(2), pp. 13 – 180.

NICHD – Nat. Inst. of Child Health and Human

Development (2000). Report of the National Reading

Panel. Teaching children to read – An evidence-based

assessment of the scientific research literature on

reading and its implications for reading instruction.

U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington DC.

Nix, D. (2006). Das Lesetheater: Integrative Leseförderung

durch das szenische Vorlesen literarischer Texte.

Praxis Deutsch 33/199, pp. 23–29.

OECD (2015). PISA 2015: Results in Focus. Available at:

https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisa-2015-results-in-

focus.pdf, [Accessed 12 August 2019].

Parr, M. (2008). More than Words: Text-to-Speech

Technology as a Matter of Self-Efficacy, Self-Advocacy,

and Choice. Available at: http://digitool.library.

mcgill.ca/webclient/StreamGate?folder_

id=0&dvs=1565529171923~291 [Accessed 12 August

2019].

Poulsen, R., Wiemer-Hastings, P. & Allbritton, D. (2007).

Tutoring Bilingual Students with an Automated

Reading Tutor That Listens. Journal of Educational

Computing Research, 36(2), 191-221.

Ribeiro, P., Iurgel, I., Müller, W. & Ressel, C. (2016).

Enrichment of Story Reading with Digital Media. In G.

Wallner, S. Kriglstein, H. Hlavacs, R. Malaka, A.

Lugmayr & H.-S. Yang (eds.), Entertainment

Computing - ICEC 2016, Springer. Cham, pp. 281–285.

Rosebrock, C., Nix, D., Rickmann C. & Gold, A. (2011).

Leseflüssigkeit fördern: Lautleseverfahren für die

Primar- und Sekundarstufe. Seelze: Kallmeyer.

Strategy Analytics (2019). Strategy Analytics: 2018 Global

Smart Speaker Sales Reached 86.2 Million Units on

Back of Record Q4. Available at: https://news.

strategyanalytics.com/press-release/devices/strategy-

analytics-2018-global-smart-speaker-sales-reached-

862-million-units, [Accessed 12 August 2019].

Vasinda, S. & McLeod, J. (2011). Extending Readers

Theatre: A Powerful and Purposeful Match With

Podcasting. The Reading Teacher, 64(7), 486-497.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

146