Career Choice of Adolescents: Can occupational VR 360-degree Videos

Facilitate Job Interest?

Pia Spangenberger

1

and Sarah-Christin Freytag

2

1

Institute of Vocational Education and Work Studies, Technische Universit

¨

at Berlin, Berlin, Germany

2

Department of Human-Machine Systems, Technische Universit

¨

at Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Keywords:

Virtual Reality, 360-degree Videos, Recruitment, Evaluation, Classroom based Learning, Career Choice.

Abstract:

The recent increase in accessibility of stand-alone Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) has been recognised by

companies who use them for recruitment purposes. By filming employees on the job site with 360-degree

cameras, jumping into an occupational environment via a HMD has become a possibility for young career

seekers. However, career choice depends on various influential factors (e.g. socialisation, self-efficacy, norms,

experiences or career choice readiness). Thus, the question arises how and if VR 360-degree videos for occu-

pational orientation can play a supporting role in this process. The presented pilot study examines the effects

of exposure to occupational VR 360-degree videos on the development of occupational interest. 41 students

experienced a variety of occupational VR 360-degree videos in a classroom setting. A significant increase in

job interest before and after exposure was found. Our results indicate a positive experience and favourable

ratings towards the application as useful for career orientation and for providing occupational information.

We conclude that VR 360-degree videos are a promising tool for gaining occupational information and initi-

ate self-reflection. We suggest future research with larger cohorts using the same VR application to further

investigate which features are regarded as helpful in career orientation for young adults.

1 INTRODUCTION

The use of 360-degree videos to promote learn-

ing goals has been increasingly discussed in recent

years (e.g. Janssen et al., 2016; Kavangah et al.,

2016; Hebbel-Seeger, 2018). Compared to 180-

degree videos, 360-degree videos are correlated with

increased immersion as well as increased motiva-

tion concerning learning (Narciso, 2019). 360-degree

videos are considered to have an added value when

using head-mounted displays (HMDs), as they in-

crease the experience of presence (Hebbel-Seeger,

2018). VR technologies are ascribed several advan-

tages in the context of education, such as enhance

knowledge or foster students’ interest (Azhar et al.,

2018). Inexpensive VR glasses, such as the Google

Cardboard, introduce the possibility of purchasing

several devices as a class set (Google VR, 2019). The

generation of virtual environments enables students

to easily access a variety of scenarios in a classroom

context without facing difficulties such as inaccessi-

bility or lack of suitable facilities within geographical

proximity. Furthermore, the experience is available to

all students, regardless of physical abilities. Students

can get personally involved.

Over the past two years, VR 360-degree videos

have been increasingly used by companies as part of

their recruitment process. In order to give potential

job candidates a first impression of professions, Ger-

man Railway company, Deutsche Bahn, for example,

uses VR 360-degree videos to present career opportu-

nities as a construction engineer or electrical engineer

(Deutsche Bahn AG, 2016). Students gain insight into

experiences on an actual work site using a VR appli-

cation.

Career choice is a complex process. It develops

over time on an individual level (Super, 1990; Got-

tfredson, 1981). According to the expectancy-value

model of career choice by Eccles & Wigfield (2002),

external and internal factors influence the decision-

making such as self-efficacy, socialisation, personal

experiences, accessible information as well as the ca-

reer readiness to be able to make a thorough decision

(Hirschi, 2011). Thus, career choice is depending

on very individual personal conditions. One predic-

tor for occupational choice is personal interest (Ec-

cles & Wigfield, 2002; Holland, 1997; Gottfredson,

1981). Holland (1997) describes personal interest

552

Spangenberger, P. and Freytag, S.

Career Choice of Adolescents: Can occupational VR 360-degree Videos Facilitate Job Interest?.

DOI: 10.5220/0009410805520558

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 1, pages 552-558

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

for an occupation as expression of one’s personality.

Hirschi and colleagues (2011; 2015), discussing ca-

reer readiness and career adaptivity, state that adoles-

cents should have the opportunity to match their per-

sonality with actual tasks of a future career. Adequate

occupational information is discussed as one impor-

tant factor to foster career readiness (Hirschi, 2011).

Referring to a VR intervention in a classroom con-

text, the same career choice intervention will be per-

ceived very differently by two individuals depending

on their personal experiences, expectations, values or

the competence to make a career decision in general

(Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Holland, 1997; Gottfred-

son, 1981). However, Hidi & Renninger (2006) point

out that personal involvement in a learning environ-

ment is a starting point for the development of inter-

est in the context of learning in a classroom setting: A

successful learning environment can be perceived as

a motivating, positive experience and in line with per-

sonal needs. Further on, long-term interest can be ini-

tiated and vocational interest be strengthened (Krapp,

2005).

In Germany, career orientation is part of the

school curriculum (Standing Conference of the Min-

isters of Education and Cultural Affairs in Germany,

2019). However, in each of the 16 German states,

it is implemented individually, either as a learning

objective across all subjects or as an own subject.

In most of the federal states, various approaches are

formulated as part of vocational orientation between

8th and 10th grade: information about different work

and career opportunities, development of competen-

cies to make a career choice, reflection of personal in-

terests, learning about gender equality, career assess-

ments, documentation of career paths, internships or

extracurricular activities. However, how to achieve

these goals and by which method, didactic approach

or material is decided by the schools or even on an

individual level by the teachers.

Since 2018, class sets of VR 360-degree videos

are available free of cost for German schools with the

aim of facilitating the above described career orienta-

tion goals. The VR 360-degree videos provide occu-

pational experiences within a variety of professions.

The videos can be used with own smartphones. How-

ever, the impact of integrating those novel presenta-

tion techniques on applicants remains unclear.

2 PRESENT STUDY

In the presented pilot study, we examine the effect of

experiencing occupational VR 360-degree videos in a

classroom setting on self-reported interest in a voca-

tional occupation by young adults. We assumed that

experiencing the HMD VR career orientation can pro-

mote individual interest in the explored vocational oc-

cupation. To examine our assumption, we conducted

a study with a class sets of VR 360-degree videos that

are available freely for German schools.

3 MATERIAL

In our study 26 different VR 360-degree videos were

available for students to choose from. The videos

were accessible via a smartphone application and dis-

played via a HMD (Destek VR Kit). The videos

were all produced by a production company for re-

cruitment purposes of different German companies.

Printed information cards on each profession pro-

vided an overview of the selections to chose from.

All professions were vocational training occupations

of the German dual system. Students could choose

out of the following professions:

• Technicians: Electronic Technician, Engineer for

Air Traffic Control, Industrial Electronics Techni-

cian, Recycling and Waste Management Techni-

cian

• Transportation: Railway Worker, Driver, Engi-

neer for Air Traffic Control

• Law Enforcement and Safety: Police Officer

• Healthcare: Nurse, Drugist, Management Assis-

tant for Healthcare, Pharmaceutical Technical As-

sistant, Pharmaceutical Commercial Assistant

• Mechanics: Ship Mechanic, Metal Cutting Me-

chanic

• Sales and Marketing: Retail Management Assis-

tant, Management Assistant for Insurance and Fi-

nance, Controller

• Hospitality and Catering: Hotel Industry Expert,

Catering Expert, Cook

• Other: Cemetery Gardener, Shipping Manage-

ment Assistant, Special Civil Engineering Works

Builder, Skilled Civil Engineering Worker

All chosen videos offered a visit at the job site, al-

lowing the students to either take on the role of an ap-

prentice or to follow a worker’s daily routine in one of

the professions described above. The videos were de-

signed to display the chosen occupation from a first-

person perspective, thus allowing the participants to

explore the typical environment they would encounter

in a real-world setting when working in the respective

field.

Career Choice of Adolescents: Can occupational VR 360-degree Videos Facilitate Job Interest?

553

4 METHOD

Our research goal aimed to identify the effects of ex-

periencing a VR 360-degree video on self-reported in-

terest levels in the chosen occupation. We assumed

that the VR experience enhances expressed interest

towards the chosen profession based on the findings

of Hidi & Renninger (2006). We further assumed that,

if the VR experience is perceived as very positive, the

increase of interest is more likely.

4.1 Sample

41 students (m=27, f=14) from two different 10th

grade classes of a secondary school in Germany par-

ticipated in the study. The students were on average

15.37 years old.

4.2 Procedure

Participants were informed that they were about to

watch one of 26 different professions virtually from

an employee’s perspective in their real working envi-

ronment. The students were informed by the provided

cards about the different occupations to choose from

and were instructed to select one. They then put on

the HMD and experienced the video of their choice,

with the length of exposure depending on the video,

ranging from three to five minutes. Trials took ap-

proximately 15 minutes to complete. Before and after

the VR session, the students were asked to fill out the

questionnaires described in the following section.

4.3 Measures

In a pre-post-test design, interest in the self-selected

professions before and after watching the VR 360-

degree video was assessed via a 5-step-Likert-scale

(with ”1=not interested at all” up to ”5=very inter-

ested”).

To investigate the VR experience, participants

were asked to fill out the In-game Scale of the Game

Experience Questionnaire (14 items) by Ijsselsteijn

(2013). The scale was chosen because it contains two

items each on flow, immersion, competence, tension,

negative and positive affects as well as challenge and

was designed to assess a user’s in-game experience

directly after exposure. The questionnaire has been

used in varied contexts to examine the digital learn-

ing applications (e.g. Janssen et al., 2016).

To gain a deeper insight into the individual expe-

riences, we queried subjective ratings on the percep-

tion of the 360-degree videos with six custom items

that the participants could rate on a five-step Likert-

scale, with ratings from 1 (”strongly disagree”) to 5

(”strongly agree”). The questions focused on the per-

ceived influence of the VR experience on their occu-

pational interest (”The occupations became more in-

teresting to me.”, ”My career aspirations have been

confirmed by the VR experience.”), the value of the

VR experience for vocational orientation (”The use of

VR-glasses facilitated comprehending everyday work

life.”) and the overall usability as well as the attrac-

tiveness of the VR experience (”It was easy for me

to handle the glasses.”, ”The displayed occupations

were more appealing to me than they were in other

career choice events.”). To account for pre-existing

interest levels, these were directly addressed (”I was

already interested in the presented job profiles before

I used the VR glasses.”). We also captured socio-

demographic data (age, type of school).

To analyse our data we calculated the differences

between reported interest before and after the VR

experience as well as effect size. Since the ob-

served measures approximated a normal distribution,

we conducted independent and dependent t-tests as

well as simple means and standard variations to in-

terpret subjective perceptions.

5 RESULTS

12 of the available videos were chosen (see table 1).

We noted a high popularity for more widely known

and generally popular occupations such as cook, re-

tail management assistant and nurse while more spe-

cialised or less common fields, such as shipping man-

agement assistant, were selected with a lesser fre-

quency.

Table 1: Overview of students’ selection of video content.

Profession Number of

selections

Cook 7

Drugist 5

Retail Management Assistant 4

Nurse 4

Management Assistant 3

Police Officer 2

Industrial Electronics Technician 2

Engineer for Air Traffic control 2

Shipping Management Assistant 1

Mechatronics Technician 1

Hotel Industry Expert 1

Electronic Technician 1

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

554

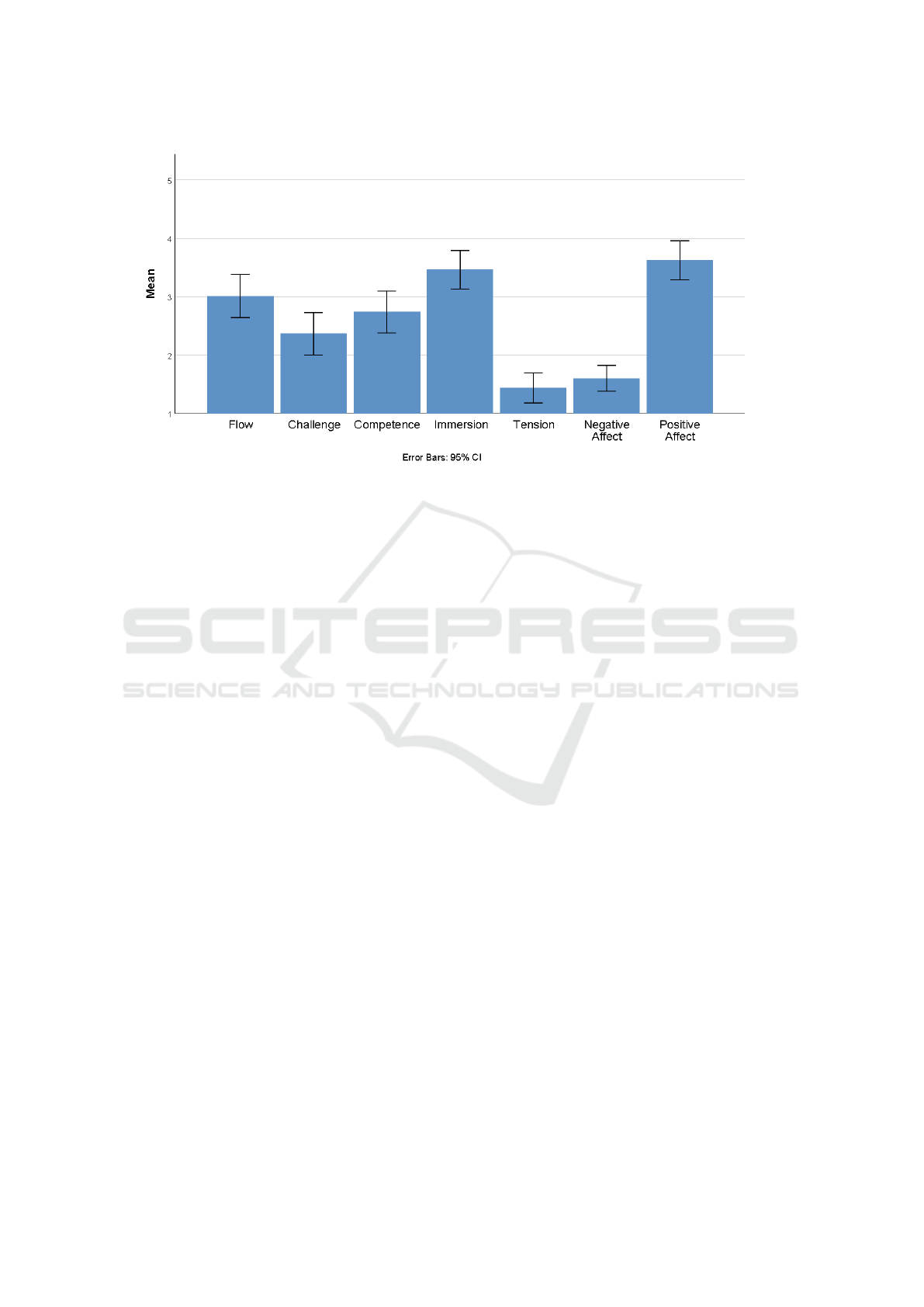

Figure 1: Means for each dimension of the Game Experience Questionnaire across all participants.

Analysing the pre-post data on interest, one par-

ticipant was omitted from the calculation since he/she

did not fill out the questionnaire, reducing the sample

to 40 participants.

After having experienced the VR 360-degree

video, 12 out of 40 participants reported an increase

in interest (30 percent), 16 out of 32 showed no differ-

ence (40 percent) and 4 out of 40 participants stated

a decrease in interest towards the selected occupa-

tion (10 percent). Eight out of all 40 participants

were not able to recall the profession they had expe-

rienced and were therefore not able to give ratings on

their interest on a pre-post item regarding the watched

video. To investigate the correlation of interest before

and after watching one of the VR 360 degree videos,

we conducted a dependent sample t-test and mea-

sured the effect size using the Cohen’s d. Interest rat-

ings were higher after having watched the VR expe-

rience (M=2.906; SE=.221) compared to the interest

ratings before exposure (M=2.531; SE=.238; t(31)=-

1.929,p=.031), reaching significance while presenting

a small effect (Cohen’s d=.341).

To assess the perception of the experience, we

evaluated the In-game scale of the GEQ by calculat-

ing means for the five-point Likert-scale according to

the manual. The data of four participants were omit-

ted from the calculation since they did not fill out the

relevant part of the questionnaire. On average, stu-

dents enjoyed the VR-experience (M=2.91; SD=.621;

N=37). The means of the individual items further

suggested an overall positive experience (see Figure

1). Students reported a positive affect, high immer-

sion and flow. They reported less tension or nega-

tive affect. Since self-reported competence and chal-

lenge was neither the learning objective of the videos

nor relevant for the main research question, it was not

considered for the analysis. No differences in enjoy-

ment were found when comparing female and male

participants (independent t-tests). Furthermore, we

found no significant correlation between in-game ex-

perience and interest in a profession after watching

a 360-degree video. No correlation between in-game

experience and failure to recall the selected profession

could be observed.

Analysing the six custom items, participants per-

ceived watching the 360 degree videos in VR a pos-

itive experience. Occupations were self-reported as

more interesting compared to the students’ interest

before seeing the video (M=3.51; SD=1.344; N=41).

The 360-degree video provided a deeper insight into

the profession (M=3.71; SD=1.188; N=41). Students

ascribed the VR 360-degree videos to facilitate com-

prehending everyday work life (M=3.63; SD=1.09;

N=41). Students highly recommended the introduc-

tion of HMDs to school lessons (M=4.22; SD=1.15).

They also perceived the application as easy to use and

uncomplicated (M=4.1; SD=.982; N=41). However,

students did not evaluate the VR experiences as an

event that would have confirmed their career aspira-

tions (M=1.80; SD=1.05; N=41). 15 of the respond-

ing participants already had a specific career aspira-

tion. No video among the interviewees evoked uni-

versally positive ratings.

Career Choice of Adolescents: Can occupational VR 360-degree Videos Facilitate Job Interest?

555

6 DISCUSSION AND

LIMITATIONS

In our study, we conducted a pilot study with 41 stu-

dents watching VR 360-degree videos via HMDs in

the context of career choice. Out of 26 videos offering

the experience of daily work environments from dif-

ferent vocational occupations, 12 videos overall were

selected by the 41 participants. A significant increase

in interest ratings regarding a chosen profession after

being exposed to it via VR 360-degree video could be

found, amounting to a small effect.

This finding is especially interesting since only

about one third of all students reported an increased

interest while the majority reported no changes. Only

four students reported a decrease in interest. This sug-

gests that students who already had a previous inter-

est in a certain field might not have needed the ad-

ditional insights the experience offered but that those

who were unsure benefited greatly. Thus, the videos

are perceived very differently, but provide an oppor-

tunity to match personal career aspirations with an ac-

tual task of a profession. Ultimately, the decrease in

interest regarding a certain profession after a VR ex-

posure might be a positive outcome for the student.

Students might have realised that their initial interest

and their expectation of their chosen profession were

either met or not met by the actual requirements of the

occupation. The employed questionnaire did not in-

corporate an assessment of the reasons for a positive

or negative rating. We suggest to integrate items ad-

dressing a possible mismatch of previous expectations

regarding the chosen vocation and the work require-

ments displayed in the VR 360-degrees video. We

also suggest to replicate the study specifically target-

ing students who have not yet decided on a preferred

vocation and who might benefit from the additional

orientation and occupational information, to investi-

gate its effects on job interest.

The comparatively high number of students who

were not able to recall the selected profession, near-

ing 20 percent, was unexpected. In our sample, all of

those participants were male. Due to the small abso-

lute number of students unable to recall, no statisti-

cal link can be established. Since previous studies on

career choice state gender differences (Wigfield et al.,

2002) as well as research on computer games have ob-

served gender differences in the perception of various

game mechanics (e.g. Hartmann & Klimmt, 2006),

an investigation of a possible link between gender and

different experiences of VR 360-degree videos in the

context of career choice with a greater number of par-

ticipants might be worthwhile.

As our sample consisted of 41 students, coming

from only two different classes at the same school,

the vocational interest and video selection reflected

the variety of personal interests of our participants.

The selection of unique occupations by nearly every

fourth student emphasises the importance to offer a

variety of vocations to chose from. The selection of

occupations was well received and proved suitable for

adolescents exploring their career options.

Regarding the individual occupational fields each,

a research design with more students interested in

the same profession, using the same VR 360-degree

video, could provide more useful data to investigate

specific job interest. The provided videos only of-

fered a brief opportunity to explore the selected fields

further. The extension of video length could possibly

further facilitate the development of interest and the

evaluation of a specific field as suitable for one’s own

interests.

Additionally, precise learning objectives could be

appointed such as self-reflection or selecting task spe-

cific information, and be evaluated. Some of the re-

spondents were subsequently unable to assign a spe-

cific job title to the work environment they had expe-

rienced in the VR environment. Apart from possible

interpersonal effects, this might also suggest that the

purpose of watching the videos was not clear to all

participants.

7 CONCLUSION AND

IMPLICATIONS

Our results demonstrate that a VR 360-degree ex-

perience with a HMD in a classroom setting could

strengthen interest in a profession and was mainly

perceived as positive, thus confirming our assumption

that exposure to a VR 360-degree video can facili-

tate job interest. The majority of the pupils stated

that they had gained better insights into the chosen

profession via the experience of the VR 360-degrees

video and that they found the presented content in-

teresting. Due to the highly individual and complex

process of career choice, each video was perceived

very differently by each student. Depending on vari-

ous influential factors, all videos about job sights will

be evaluated through a filter of an individual world of

experience, standards, attitudes and abilities as well

as a personal level of career readiness, which needs to

be taken into account when evaluating the effects of

occupational interest interventions.

On average, most of the participating students

would recommend the use of VR 360-degree videos

at school lessons. Apart from the described limita-

tions, the VR experience seems to provide an insight

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

556

into a profession that otherwise might not be possible

without further effort. VR-360 degree videos enable

experiences at locations which young people usually

have no access to plus more than one in short time.

For instance, visiting the job sight of an offshore wind

power plant is not possible due to safety restrictions

(Spangenberger et al., 2019).

For future research, it would be of interest to investi-

gate the influence of 360-degree videos in context of

a non stereotypical career choice. In our study, only

two male participants chose a profession in the field of

healthcare, stereo-typically perceived as a female do-

main, while all students who chose the profession of

a cook were male. In future research projects, the de-

sign and evaluation of VR 360-degree video features

that promote specific job interest could be focused.

We conclude that the application of 360-degree

videos for career assessment in a classroom setting

is generally suitable to meet the needs of students in a

career orientation phase. Watching different VR 360-

degree videos can be a helpful tool not only to offer

occupational information but also to reflect personal

aspirations by exploring a diversity of tasks on the

job site that might otherwise not have been associ-

ated with working in that field. Since they were well

perceived by the target group, VR 360-degree videos

have the potential to engage students in an learning

environment that is perceived as motivating and posi-

tive.

Furthermore and in line with the literature on ca-

reer choice, we suggest to not only focus on enhanc-

ing interest in a specific field, but to also specifi-

cally employ the VR experience to uncover possible

mismatches between previous interests and the real-

ities of occupational requirements. This could pre-

vent young adults from choosing a non-suitable voca-

tional training and therefore having to switch career

paths later. Having VR 360-degree videos available

for each student in a classroom gains new potentials

in the field of career orientation. In our pilot study the

experience was well received and regarded as help-

ful. We suggest further investigations with larger co-

horts and also the exposure of each student to a larger

variety of videos. We further suggest to embed the

experience as a multi-faceted vocational orientation

program focusing on self-reflection and discussion of

the occupational information.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Julie Bossier for preparing the

questionnaires and conducting the interviews.

REFERENCES

Azhar, S., Kim, J., & Salman, A. (2018). Implement-

ing Virtual Reality and Mixed Reality Technologies

in Construction Education: Students’ Perceptions

and Lessons Learned. Paper presented at 11th an-

nual International Conference of Education, Novem-

ber, 2018. doi: 10.21125/iceri.2018.0183

Google VR (2019). Das Google Cardboard.

https://arvr.google.com/intl/de de/cardboard/get-

cardboard/

Deutsche Bahn AG. (2016). Entdecke Deinen

Traumjob in 360

◦

. Retrieved from http://vr-

karriere.deutschebahn.com/

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Moti-

vational Beliefs, Values and Goals. An-

nual Review Psychology, 53, 109–132.

doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

Gottfredson, L. S. (1981). Circumscription and Compro-

mise: A Developmental Theory of Occupational As-

pirations. Journal of Counseling Psychology Mono-

graph, 28(6), 545–579.

Hebbel-Seeger, A. (2018). 360

◦

-Video in Trainings- und

Lernprozessen. In Dittler, U.; Kreidl, C. (Hrsg.),

Hochschule der Zukunft. Springer Fachmedien, Wies-

baden; pp. 265–290.

Hidi, S.; Renninger K. A. (2006) The Four-Phase Model

of Interest Development, Educational Psychologist,

41:2, 111-127, doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep4102 4

Ijsselstein, W.A., de Kort, Y.A.W., & Poels, K. (2013). The

Game Experience Questionnaire. Eindhoven. Technis-

che Universiteit Eindhoven.

Kavanagh, S., Luxton-Reilly, A., Wuensche, B., & Plim-

mer, B. (2016). Creating 360

◦

educational videos. In

Duh, H. et al. (Hrsg.): Proceedings of the 28th Aus-

tralian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction -

OzCHI ’16. ACM Press, New York, USA. pp. 34–39.

DOI: 10.1145/3010915.3011001

Krapp, A. (2005). Basic needs and the develop-

ment of interest and intrinsic motivational orien-

tations. Learning and Instruction, 15(5), 381–395.

doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.007

Hartmann, T., & Klimmt, C. (2006). Gender and

Computer Games: Exploring Females’ Dislikes.

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication,

11(4), 910–931. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-

6101.2006.00301.x

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A the-

ory of vocational personalities and work environments

(3rd ed.). Odessa, Fla: Psychological Assessment Re-

sources.

Hirschi, A. (2011). Career-choice readiness in ado-

lescence: Developmental trajectories and individual

differences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2),

340–348. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.005

Hirschi, A., Herrmann, A., & Keller, A. C. (2015). Career

adaptivity, adaptability, and adapting: A conceptual

and empirical investigation. Journal of Vocational Be-

havior, 87, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2014.11.008

Career Choice of Adolescents: Can occupational VR 360-degree Videos Facilitate Job Interest?

557

Janssen, D., Tummel, C., Richert, A., & Isenhardt, I.

(2016). Towards Measuring User Experience, Ac-

tivation and Task Performance in Immersive Virtual

Learning Environments for Students. In: Colin Alli-

son, Leonel Morgado, Johanna Pirker, Dennis Beck,

Jonathon Richter und Christian G

¨

utl (Hg.): Immer-

sive Learning Research Network, Bd. 621. Cham:

Springer International Publishing (621), S. 45–58.

Narciso, D., Bessa, M, Melo, M., Coelho, A., &

Vasconcelos-Raposo, J. (2019). Immersive 360

◦

video

user experience: impact of different variables in the

sense of presence and cybersickness. Universal Ac-

cess in the Information Society, 18; pp. 77–87.

Spangenberger, P., Kapp, F., Kruse, L., & R

¨

otting, M.

(2019). A Mixed-Reality Learning Application to

Experience Wind Engines for Beginner and Experts.

In Lars Elbæk, Gunver Majgaard, Andrea Valente

and Md. Saifuddin Khalid (Ed.), Proceedings of the

13th European Conference on Game Based Learning

(ECGBL) 2019, Odense, Denmark, Ocotber 3-4. pp.

1041-1044. Reading: ACPIL

Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and

Cultural Affairs in Germany, (2019). Documenta-

tion for vocational orientation at general education

schools. (Resolution passed at the Standing Confer-

ence of Education and Cultural Affairs in Germany at

07.12.2017 in the version of 13.06.2019).

Super, D. E. (1990). A Life-Span, Life-Span Approach

to Career Development. In D. Brown, L. Brooks,

& and associates (Eds.), Career choice and develop-

ment. Applying contemporary theories to practice. A

joint publication in The Jossey-Bass Management Se-

ries and The Josse-Bass Social and Behavioral Sci-

ence Series (2nd ed., pp.197–261). San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Occulus (2019). Mission ISS.

https://www.oculus.com/experiences/rift/1178419975

552187/

Wigfield, A, Battle, A., Keller, L., & Eccles, J. (2002).

Sex Differences in Motivation, Self-Concept, Career

Aspiration and Career Choice: Implications for Cog-

nitive Development. In A. McGillicuddy-De Lisi &

R. De Lisi (Eds.), Advances in applied developmental

psychology, Vol. 21. Biology, society, and behavior:

The development of sex differences in cognition (p.

93–124). Ablex Publishing.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

558