Augmentation of Interactive Science Communication

using Sign Language

Miki Namatame

*

and Masami Kitamura

Department of Industrial Information, National University Corporation Tsukuba University of Technology,

4-3-15 Amakubo, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan

Keywords: Science Communication, Aquarium, Information Accessibility, Sign Language.

Abstract: Learning outside of a school environment is important for us because much of our time is spent outside of

school. Museums, in particular, are important for lifelong learning. To improve accessibility of information

for science communication in museums based on the principles of “universal design” and “design for all,” we

consider universal access for d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors. This paper introduces the necessity of

improving information accessibility for d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors, followed by specific methods for

them to learn freely and spontaneously in aquariums. Curators who were able to use sign language to provide

scientific communications were trained, and then accessibility methods acceptable to d/Deaf and hard-of-

hearing visitors to augment interactive science communication in aquariums were surveyed through a

demonstration experiment. Four information guarantees were provided: distribution of explanations,

explanations by sign language interpreters, sign language explanations with signboards, and face-to-face

lectures in sign language. The merits and demerits of each type of information accessibility were assessed via

a questionnaire.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since the establishment of the Disability

Discrimination Act (ADA) in 1995, advocacy for

persons with disabilities has been a priority for most

institutions. Museums have therefore continued to

proceed with concepts of the “inclusive museum”

(GMA, 2017) and universal access (Smithsonian

2011).

However, Atkinson (2012) has warned that, while

exploring a museum collection constitutes a very

visual experience, “deaf audiences are one of the most

neglected by museums.” Martins (2016) reported that

deaf visitors’ engagement is enhanced when tours are

given by deaf tour guides. Goss (2015) advised that a

wide range of multilingual communication needs is

required for a diverse range of museum visitors who

are d/Deaf or hard-of-hearing.

Unfortunately, there are few museums taking such

actions in Japan. Most content for people with hearing

disabilities is insufficient from the viewpoint of

universal design and accessible design. Therefore, we

*

https://www.tsukuba-tech.ac.jp/english/

undergraduate_schools.html

aim to explore the different communication resources

required by d/Deaf or hard-of-hearing visitors to

break down the barriers they face in science

museums. d/Deaf or hard-of-hearing visitors to

museums can be categorized into three groups: 1)

Spoken-Focused, 2) Simultaneous Language, and 3)

Sign Language-Focused (Goss, 2015). In this study,

we focused on sign language users.

2 RELATED RESEARCH

In this section, we explain our previous studies to

improve information accessibility for visitors to

aquariums who are d/Deaf or hard-of-hearing.

We conducted a survey of people with hearing

impairment concerning museums, including art

museums, science museums, historical museums,

culture halls, botanical gardens, zoos, and aquariums.

We obtained responses from 70 people with

hearing disabilities. We asked them 27 questions,

from June 30th, 2017 to February 21st, 2018.

Namatame, M. and Kitamura, M.

Augmentation of Interactive Science Communication using Sign Language.

DOI: 10.5220/0009410203150319

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 2, pages 315-319

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

315

The following graph (

Figure 1)

shows the result for

the question: “Have you ever been to a museum?”

Among d/Deaf or hard-of-hearing people, 93% had

visited the aquarium, 89% the zoo, and 77% the

science museum. No person was found who did not

have the experience of using at least one of these

museums.

These results show that museums were popular

among people with hearing loss. However, their

opinions were as follows.

1. Most explanations are verbal, so I am in

trouble.

2. I do not visit because I cannot obtain

information and enjoy it.

3. I want to know more! I want to learn more!

4. Because there is no sign language

interpreter, I don’t know what I want to

know.

Opinions 1–3 show the need to devise information

accessibility for d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors

to learn independently and spontaneously at

aquariums and with freedom and enjoyment at

museums (Falk, 2001). Therefore, we initially

provided Japanese sign language explanations via

Quick Response (QR) code technologies at an

aquarium in Japan. The demonstration experiment for

d/Deaf or hard-of-hearing people was conducted at

the aquarium on November 27th, 2018. The opinions

of eight participants were gathered via a

questionnaire. An opinion was also expressed that

explanations in sign language are more impressive

than written explanations. People highly appreciated

being able to watch the sign language commentary

while observing the fish. We investigated the effect

of sign language content with experimental proof

(Namatame, 2019), including Japanese sign language

content published on an official aquarium website in

September 2019 (Figure 2). This content has grown

to 1,500 pageviews per month.

However, this method could not solve the

aforementioned opinion no. 4, so d/Deaf curators

were nurtured in our educational program to remove

the science communication barriers that accompanied

interactive conversations. The training program was

conducted from September 7th, 2019, to December

5th, 2019. The curators required conversational skills

to provide visitors with new knowledge and excite

their curiosity as well as the ability to answer

questions correctly (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Current status of museum usage (hearing loss).

Figure 2: Screenshot of sign language content.

Figure 3: Snapshot of the face-to-face lecture.

The background of the tank

resembles the deep sea

habitat; one can imagine

what it’s like 1,500 meters

beneath the waves.

Deep Sea Jellyfish

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

316

3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND

METHODS

To remove barriers to scientific communication

associated with interactive conversations in the

aquarium, we extracted concrete scenes and

attempted solutions based on a demonstration

experiment, in which people who were d/Deaf or

hard-of-hearing participated.

Our research questions were as follows.

1. What is the most accepted method of

augmenting interactive science

communication in an aquarium for d/Deaf or

hard-of-hearing visitors?

2. What are the acceptable and/or unacceptable

features of such methods?

4 RESEARCH DESIGN

Specifically, the following, which guaranteed

information accessibility for the disabled, was

prepared to obtain evaluations through a

demonstration experiment and attempt to identify

problems.

1. Distribute the explanation documents for the

curator’s audio commentary.

2. Support the curator’s sign language

commentary with a signboard displaying

Japanese written text.

3. Have a sign language interpreter collaborate

with the curator’s audio commentary.

4. Provide explanations in sign language by a

curator with a hearing impairment through

face-to-face communication.

The demonstration experiment participants

enjoyed the exhibition together with the general

public. Once the aforementioned experiment was

completed, the participants evaluated it via a

questionnaire.

The evaluations used a six-step Likert scale (1:

strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: somewhat disagree,

4: somewhat agree, 5: agree, 6: strongly agree) and

were separated into two for totalization (agree or

disagree). Participants were required to provide the

reasons for their evaluations.

5 RESEARCH

IMPLEMENTATION

The demonstration experiment at the aquarium was

conducted on November 29th, 2019. Five university

students who were d/Deaf or hard-of-hearing

participated. Their sign language career experience

was about 20 years (the career of one person was four

years), and they were regular sign language users. All

the participants liked the aquarium. They followed

the exhibits along the aquarium route. Information

accessibility for d/Deaf or hard-of-hearing

participants with voice commentary had been

prepared at the following popular points.

1. Sunfish lunchtime (distribute explanation

documents of the curator’s audio

commentary.)

2. Sand tiger shark profile (support curator’s

sign language commentary with a signboard

displaying Japanese written text.)

3. How to distinguish between male and female

sharks (have a sign language interpreter

collaborate with the curator’s audio

commentary.)

4. Lecture on shark eggs and skin (sign

language explanation by a curator with a

hearing impairment through face-to-face

communication.)

5. Aqua watching in front of the main tank (free

time without information accessibility

support).

Figure 4: Snapshot of the scene supported by a sign

language interpreter.

6 RESULTS

In this experiment, the most interesting content was

the lecture on shark eggs and skin, which was selected

by three participants, followed by the shark sexing

Augmentation of Interactive Science Communication using Sign Language

317

method, which was selected by two participants. The

main reasons included the utility of sign language

such as “I could ask questions without hesitation” and

“It was an enjoyable and understandable way to

obtain information.” Another perspective considered

learnability, i.e., “I acquired new knowledge” and “I

obtained explanation details.”

Participants who visited Exhibitions 1 and 5 were

dissatisfied because they found them difficult to

understand. Exhibition 1: Real-time comments were

required, not description documents. Exhibition 5: It

seemed like just feeding and was not interesting

because only voice information was provided and I

could not gain the information such as sunfish life.

There was a problem in Exhibition 2 with the

visibility of the signboard, and there was an

unavoidable time lag in the interpretation in

Exhibition 3.

Nevertheless, thanks to effective sign language

and sign classifiers, the exhibitions were very

imageable for participants. The lively discussion

using the haptic materials made the interactive

communication easy to understand.

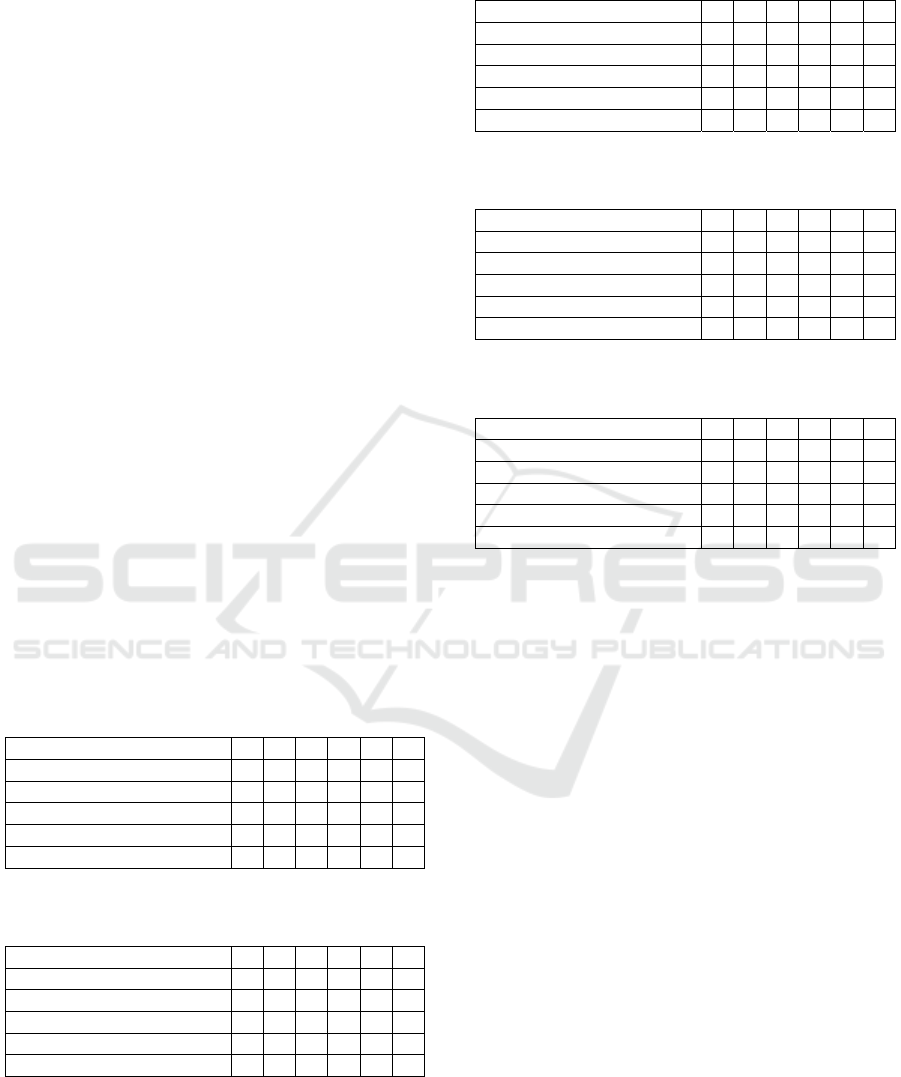

The evaluations of the content are presented in

Tables 1 to 5. Enjoyment of “Shark eggs and skin”

was evaluated with a high score (Table 1), while the

satisfaction, understandability, and learnability of

contents supported by sign language were also

evaluated highly (Tables 2, 3, 4). “Aqua watching”

had no support, and few participants wished to revisit

it.

Table 1: Evaluation of enjoyment (number of participants/

disagree 1–3, agree 4–6).

CONTENT 1 2 3 4 5 6

Sunfish 0 0 1 3 0 1

San

d

tiger shar

k

0 0 0 2 2 1

Shark sexing 0 0 0 1 3 1

Shark e

gg

s and skin 0 0 0 1 0 4

A

q

ua watchin

g

1 0 0 1 1 2

Table 2: Evaluation of satisfaction (number of participants/

disagree 1–3, agree 4–6).

CONTENT 1 2 3 4 5 6

Sunfish 0 0 1 2 1 1

San

d

tiger shar

k

0 0 0 1 2 2

Shark sexing 0 0 0 0 2 3

Shark eggs and skin 0 0 0 1 1 3

A

q

ua watchin

g

1 0 1 0 1 2

Table 3: Evaluation of understandability (number of

participants/disagree 1–3, agree 4–6).

CONTENT 1 2 3 4 5 6

Sunfish 0 1 2 1 1 0

San

d

tiger shar

k

0 0 0 2 1 2

Shark sexin

g

0 0 0 1 1 3

Shark e

gg

s and skin 0 0 0 1 2 2

A

q

ua watchin

g

1 0 1 3 0 0

Table 4: Evaluation of learnability (number of participants/

disagree 1–3, agree 4–6).

CONTENT 1 2 3 4 5 6

Sunfish 0 0 0 1 3 1

San

d

tiger shar

k

0 0 0 0 2 3

Shark sexing 0 0 0 0 3 2

Shark e

gg

s and skin 0 0 1 0 1 3

A

q

ua watchin

g

2 0 1 0 1 1

Table 5: Evaluation of intention to revisit (number of

participants/ disagree 1–3, agree 4–6).

CONTENT 1 2 3 4 5 6

Sunfish 0 0 1 3 1 0

San

d

ti

g

er shar

k

0 0 0 0 3 2

Shark sexing 0 0 0 0 3 2

Shark eggs and skin 0 0 0 1 2 2

A

q

ua watchin

g

1 0 0 1 3 0

7 DISCUSSION

The most acceptable method of guaranteeing

information accessibility for d/Deaf or hard-of-

hearing visitors at an aquarium was not identified by

this demonstration experiment. However, acceptable

features for d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors were

clearly observed. Providing specific explanations led

to audience satisfaction. Furthermore, if a curator

explained an exhibition in sign language directly, the

audience understood easily and asked questions

without hesitation. It is certain that sign language is

needed to augment science communications. In

addition, the darkness of the lighting environment, a

unique problem of museums, was revealed.

Sign language and sign language classifiers have

the power to turn abstract concepts, including jargon,

into rich, visual expressions. Simultaneous sign

language and audio commentary is able to provide

scientific communication for both hearing and deaf

people. We think this is one way to make science

communication easy for everyone to understand.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

318

8 CONCLUSIONS

To achieve this goal, we will be improving

information accessibility for the d/Deaf and hard-of-

hearing at the aquarium based on the principles of

universal design and human-centered design. Our

goal is to promote museums to the public for purposes

of education, study, and enjoyment without

disabilities. In the future, we intend to develop a

system to convey the meaning of and interest in sign

language to all audiences.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant

Number 18H01046 and Contract Research of Ibaraki

Prefecture. This study was approved by the research

ethics committee of the Tsukuba University of

Technology (H30-4). We thank Aqua World Ibaraki

Prefectural Oarai Aquarium and the Tsukuba

University of Technology students who helped with

the research.

REFERENCES

Abell, K. M., Lederman, G. M., 2007. Handbook of

Research on Science Education. Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Atkinson, R., 2012. Opening up museums to deaf audiences.

Museum Practice, Museums Association.

https://www.museumsassociation.org/museum-

practice/15022012-deaf-audiences-news, date accessed

1st. Jan. 2020.

Falk, H. J., Donovan, E., Woods, R., 2001. Free-choice

Science Education, how we learn science outside of

school. Teachers College Press.

German Museum Association, 2017. Inclusive museum.

https://www.museumsbund.de/inklusion/, last accessed

2020/1/1.

Goss, J., Kollmann, E. K., Reich, C., Iacovelli, S., 2015.

Understanding the Multilingualism and

Communication of Museum Visitors who are d/Deaf or

Hard of Hearing. Museums & Social Issues. Vol. 10,

52–65.

Hamraie, A., 2017. Building Access: Universal Design and

the Politics of Disability. In Univ Of Minnesota Press.

3

rd

edition.

Namatame, M., Kitamura, M., Wakatsuki, D., Kobayashi,

M., Miyagi, M. and Kato, N., 2019. Can Exhibit

Explanations in Sign Language Contribute to the

Accessibility of Aquariums? 21st International

Conference on Human-Computer Interaction.

Proceedings Part I, Vol. 33, 289–294.

Smith, J. M., Salvendy, G., 2011. Human Interface and the

Management of Information. Interacting with

Information: Symposium on Human Interface 2011,

Springer Science & Business Media.

Smithsonian Institution Accessibility Program (2011);

Smithsonian Guidelines for Accessible Design,

http://www.bu.edu/ah/files/2018/12/Smithsonian-

Guidelines-for-Accessible-Design.pdf, last accessed

2020/2/14.

Paciello, M., 2000. Web Accessibility for People with

Disabilities. CRC Press. 1

st

edition.

Augmentation of Interactive Science Communication using Sign Language

319