Design Recommendations for Successful Cross-university

Collaborative Group Work: Two Best Practices Cases

Alexander Clauss

1

and Helge Fischer

2

1

Chair of Information Management, TU Dresden, Germany

2

Media Centre, TU Dresden, Germany

Keywords: Cross-university Collaboration, Collaborative Learning, Virtual Teamwork, Virtual Collaborative Learning.

Abstract: The ability to work in decentralised, location-independent, international teams using collaborative

information and communication technology (ICT) has become an essential key competence for the vocational

capability of knowledge workers all over the world. Nevertheless, curricular contents in higher education do

not yet reflect the development of these key competencies to an extent commensurate with their crucial

importance. Concrete best practice application cases and design recommendations are lacking, especially in

a cross-university context. The aim of this paper is therefore to introduce the concept of virtual collaborative

learning (VCL) and compare two concrete application cases of cross-university VCL-arrangements in formal

learning settings in order to create a design framework and to derive concrete design recommendations. The

multi-perspective evaluations of the presented cases show that successful cross-university VCL concepts are

characterized by the e-tutorial support of group work, transparent learning objectives and evaluation criteria,

the selection of relevant, realistic and job related topics and assignments, the intensive participation of the

learners, formative feedback as well as learning analytics. Based on lessons learned during the cross-

university online collaborations concrete design measures for the implementation of cross university VCL

courses are derived.

1 INTRODUCTION

Two major trends on the labour market are the

transformation from manufacturing to knowledge

work and the distribution of work over large

geographical distances. The ability to work in

decentralised, location-independent, international

teams using collaborative information and

communication technology (ICT) has become an

essential key competence for the vocational

capability of knowledge workers all over the world

(Perez-Sabater, Montero-Fleta, MacDonald, &

Garcia-Carbonell, 2015). Both the European Union

and the OECD highlight collaboration skills, virtual

communication, problem solving, the purposeful use

of networked online tools, the development of social

skills and the creation of digital content as central key

competencies for the 21st century (Carretero,

1

The origin of this widespread quote seems controversial,

as Gunderson, Roberts, & Scanland (2004) asociate it

with a former U.S. Secretary of Education Richard

Riley, while Fadel, author of “21st Century Skills.:

Vuorikari, & Punie, 2017; Fadel, 2008; OECD, 2018;

Trilling & Fadel, 2009; Vuorikari, Punie, Carretero

Gomez, & Van den Brande, 2016). The following

general objective of higher education was already

defined in 2010:

“We are currently preparing students for jobs

and technologies that don’t yet exist... in order to

solve problems that we don’t even know are problems

yet.”

1

The development of new jobs and collaborative

technologies has been exponential during the last

decade. Nevertheless, curricular contents in higher

education do not yet reflect the development of these

key competencies to an extent commensurate with

their crucial importance (Aktas, Pitts, Richards, &

Silova, 2017; Lönnblad & Vartiainen, 2012; Perez-

Sabater et al., 2015; Simm & Marvell, 2017).

Learning for Life in Our Times” (Trilling & Fadel,

2009), refers to the well-known YouTube video "Did

You Know; Shift Happens“ by Fisch & McLeod (2007)

as source.

238

Clauss, A. and Fischer, H.

Design Recommendations for Successful Cross-university Collaborative Group Work: Two Best Practices Cases.

DOI: 10.5220/0009385202380248

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 1, pages 238-248

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

Experts criticise that, despite broad theoretical

competence frameworks, concrete best practice

application cases and design recommendations are

lacking (Erdoğan, 2015; Garrison & Kanuka, 2004;

Rovai & Downey, 2010), especially in an cross-

university context (Pisoni, Marchese, & Renouard,

2019). The aim of this paper is therefore to compare

two concrete application cases of virtual collaborative

group work in formal learning settings in order to

create a design framework and to derive concrete

design recommendations. Two different application

scenarios are described, implemented design

measures and concrete interventions in the scenarios

are presented. The two cases were evaluated using

two different evaluation approaches with different

research objectives. In the first case, the focus was on

the perceived usefulness of interventions and in the

second case, on the identification of success factors

of collaborative group work from the students'

perspective. By combining the two evaluation

approaches and research objectives, new findings are

derived. The cases presented, their multi-perspective

evaluation and the analysis of the lessons learned are

aimed at answering the following research question:

Which design measures facilitated successful cross-

university collaborative group work?

The underlying theoretical core concepts as

conceptual basis for the comparison of the two

application cases and the subsequent development of

design recommendations will be presented in the

following.

1.1 Computer Supported Collaborative

Learning

Learning is defined as the process of acquiring new

or changing existing knowledge, skills, behaviour,

values or preferences (Gross, 2015). Learning can

occur either individually or as a group activity.

According to Dillenbourg (1999), group learning

processes can be distinguished in cooperative and

collaborative learning. In contrast to cooperative

learning, in which the learners are able to segment a

group task and approach individual parts on their own

responsibility, collaborative learning requires, that

the group accomplishes the task together through

joint development, discussion and common

agreement on a group result.

Computer supported collaborative learning

(CSCL) refers to situations in which computer

technology has a crucial contribution to the design of

collaboration within the learning process (Goodyear,

Jones, & Thompson, 2014). Technology can enhance

collaborative learning in multiple ways. It can

provide, for example, a visual representation of the

task, the collaborative product or the most important

aspects of the process (Kay, Reimann, & Diebold,

2007; Suthers & Hundhausen, 2003). Furthermore, it

can serve as a tool for structuring content and

knowledge development (Lu, Lajoie, & Wiseman,

2010; Marttunen & Laurinen, 2001; Scardamalia &

Bereiter, 2006). CSCL can occur face-to-face, from a

distance, or in combinations of presence and remote

activities (a presence workshop followed by an online

discussion). It includes synchronous (real-time) and

asynchronous channels of communication. The

positive effect of (computer-aided) cooperation in

learning has been empirically confirmed several

times. In general, meta-analyses and systematic

literature reviews show that the results of

collaborative learning are superior to those of

individual and competitive learning situations

(Hattie, 2009; Johnson & Johnson, 1987; Slavin,

1990; Webb & Palincsar, 1996).

1.2 Virtual Collaborative Learning

Virtual Collaborative Learning (VCL) is a suitable

framework that exploits this potential. It is a best

practice framework for innovative blended learning

arrangements, based on years of scientific research at

the Chair of Business Informatics, esp. Information

Management led by Professor Schoop at the TU

Dresden (Balázs, 2005; Rietze, 2019; Tawileh, 2017).

Blended learning refers to the "didactically

meaningful combination of traditional classroom

learning and virtual or online learning on the basis of

new information and communication technologies

(Seuferth & Mayr, 2002). VCL has been used

continuously in formal learning modules since 2001.

VCL arrangements transfer group lessons into the

virtual space. A high level of self-organisation is

required within the groups, as all members of the

group are responsible for their joint work results. The

students work on authentic business cases with clear

practical relevance for a short time period of usually

six weeks. Due to their blended learning character

VCL-scenarios have the phases of knowledge

acquisition, virtual group work and assessment. In

order to enable working interdisciplinary and multi-

perspectively, the students have to adopt different

roles, which are often related to their interdisciplinary

study programmes. For their exchange and process

documentation, participants use social software and

digital communication tools. Learners are supported

in their collaboration by qualified e-tutors to

maximise both individual and group learning

outcomes. VCL focuses on the learning outcomes -

Design Recommendations for Successful Cross-university Collaborative Group Work: Two Best Practices Cases

239

intercultural awareness, the ability to collaborate, the

purposeful use of social tools and case study work -

and offers successful students from all participating

locations ECTS (European Credit Transfer System)

credits and grades based on formative and summative

assessments. "Formative evaluation includes all

activities of the teacher and/or the learner that provide

information that can be used as feedback, to modify

teaching and learning activities" (Black & Wiliam,

1998). The general aim is to recognise and respond to

students' learning to improve it during the learning

process (Cowie & Bell, 1999). Summative evaluation

in contrast is the final evaluation of the created

assignments (Scriven, 1967). The VCL framework is

content-independent. It can be used for a wide range

of formal education topics, for example knowledge

management, intercultural communication or digital

learning.

VCL scenarios offer opportunities for exchange

regarding cross-university collaboration. In the

framework of VCL, students can take courses beyond

the borders of their own university or exchange ideas

with students of similar study programs without

physically leaving their home university. However,

such scenarios are extremely demanding in terms of

their design, implementation and organization.

Various institutional, curricular and cultural

dimensions must be included in the planning of VCL

scenarios, which reflect the individual characteristics

of the respective institutions or study programs. This

article therefore tries to derive and document the

success factors in the planning and implementation of

cross-university VCL scenarios.

2 CASE 1: DEVELOPMENT OF

LEARNING MATERIALS VIA

VCL

The VCL course of case 1 was held in cooperation of

two universities in Germany. One student group was

from the master programm “Further Education

Research and Organisational Development” of the

Dresden University of Technology and the other

group was from Bachelor programm “Media

Communication” of Chemnitz University of

Technology. Both groups study in the fields of

educational management and instructional design

(Breitenstein, Dyrna, Heinz, Fischer, & Heitz, 2018).

The main objective of the course was to create

ten-minute multimedia learning sequences in

working groups across universities facilitated by

educational technologies. As a result, a set of media

products were created: apps, videos, screencasts and

websites. A multilevel didactic concept including a

largely self-organized group work, which is

accompanied by e-tutors, was developed.

2.1 Design Measures in Case One

The following design measures were implemented in

this VCL setting:

Knowledge Acquisition. In presence, students were

provided with relevant content on the main topics, the

use of digital media in further education and

instructional design. The knowledge transfer took

place in joint sessions, some of which were

transmitted live to the other location using Adobe

Connect. On the basis of this content and the

knowledge acquired, the students developed their

own topics for the creation of the digital learning

sequences, which were processed as part of the group

work across the universities.

Group Work. In the second phase, the students

worked in mixed groups on the content and didactic

design as well as on the technical implementation of

the learning sequences. For the implementation, a

concept was first developed in groups, in which

learning goals, subject content and didactic and

technical requirements were taken into account. Then

the lecturers and e-tutors of both universities

evaluated the concept. The students received written

contend related feedback, which could be discussed

within facultative expert constultations.

Assessment. The last step was the final presentation.

This has been gamified by letting the groups compete

against each other by pitches. They presented their

products in short presentations in an online meeting

via Skype. These were assessed both by the students

and by the team of tutors and lecturers. Basis of the

assessment of the group work was a criteria checklist,

in which the individual group performances

(conception, first beta draft of the learning sequence,

final product, presentation, fulfilment of milestones)

were analysed.

To support the virtual group work several

interventions have been implemented, e.g.

e-Tutor Support: Each of the groups was

supported by an e-tutor tandem. The e-tutors

had complementary foci. One e-tutor focused

on technical and instructional psychology and

the second e-tutor on content and didactics.

They advised the students on their requests and

facilitated the realisation of the learning

sequences.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

240

Content Related Feedback: In the process of

the course, the students created a first beta draft

on which they received content related

feedback from tutors and the supervising

lecturers with regarding the priorities: Subject

content, didactics and technical

implementation.

Expert Consultations: The students were

offered the opportunity to take part in

facultative expert consultations to discuss the

reviews of the lecturers and tutors on their

drafts.

Conceptual Templates: The project team

prepared templates for the creation of the

concept for the learning sequences.

Group Work Concepts: The students were

provided with a group work concept. This

concept presented a total of six different areas

of responsibility (subject contents/didactics,

technology, legal aspects, quality,

planning/coordination, documentation) and the

associated tasks involved in the development of

a digital learning sequence.

Quality Assurance Guidelines: The students

were provided with quality assurance

guidelines in the form of a checklist, which

they were asked to follow when implementing

the learning sequence.

Storyboard Templates: The project team

prepared templates for the development of the

storyboard.

Group Contracts: Group work began with the

conclusion of a group contract. In this contract,

the students agreed on their areas of

responsibility and decided for a project

manager in their group. This person was

primarily responsible for coordinating and

ensuring communication between lecturers, e-

tutors and the group.

2.2 Evaluation of Case One

In total, 51 participants took part in the course and the

final evaluation. The sample consists of 30

undergraduates (77 % female) in the bachelor

program and 21 master candidates (76 % female).

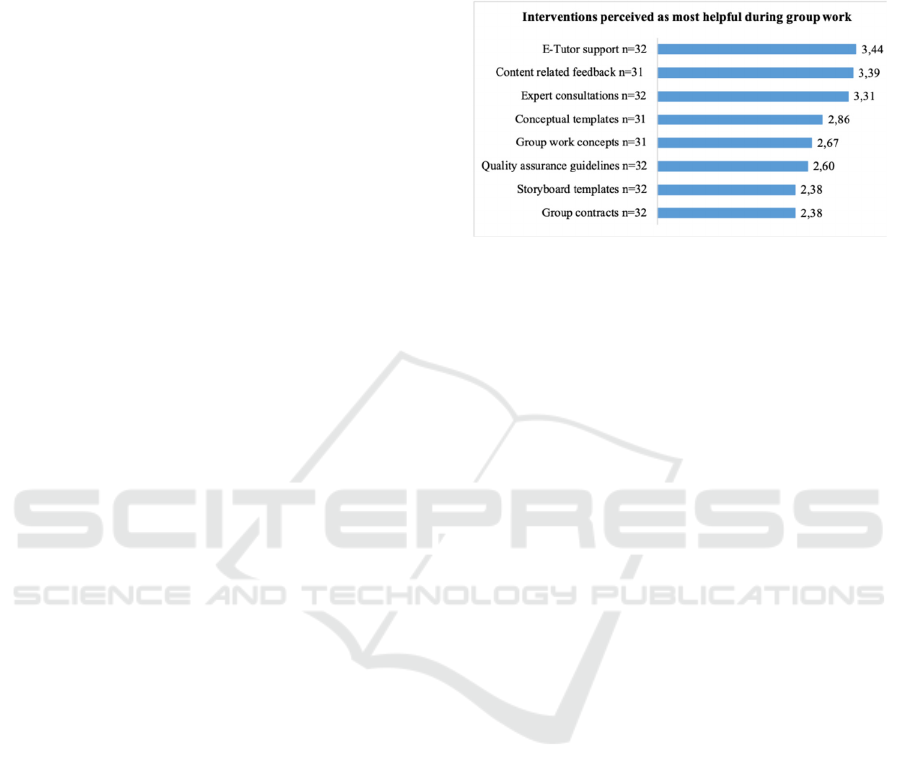

One part of the analysis was the evaluation of the

above mentioned interventions of the virtual group

work. Those were to be rated regarding to their

perceived helpfulness. It indicates that the students

predominantly perceived any kind of support or

feedback provided by experts (i.e., the lecturer and

the tutors) as most helpful. Furthermore, the provided

conceptual aids (i.e., templates for the teaching and

group concept and quality assurance criteria) were

assessed to be of above average helpfulness. In sum,

six out of the total eight described interventions were

perceived as rather helpful (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Evaluation of Interventions (Breitenstein et al.,

2018).

3 CASE 2: HUMAN RESOURCE

MANAGEMENT

Case 2 was held in Germany as part of a cross-

university cooperation between the business and

economics faculties at the “Technische Universität”

(TU) Dresden, as a full university, and at the

“Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft” (HTW)

Dresden, as a university of applied sciences. The

students were Bachelor's and Diploma students and

interdisciplinary mixed. These disciplines included

business, business informatics, business education

and industrial engineering from the technical

university and business from the university of applied

sciences.

The aim of the project, which spans two different

types of higher education institutions, is to implement

a learner-centred and integrative course on the subject

of human resources management. Didactically

prepared case studies, made available in the virtual

classroom under teletutorial supervision for

processing in mixed small groups, enable an

application-oriented deepening of subject knowledge

and are intended to create awareness of real-life

business situations. Furthermore, active work on

authentic and practical scenarios promotes the

development of social skills, media skills and self-

organisation skills of students (Tawileh, Bukvova, &

Schoop, 2013). Thereby the participants are

supported by specially qualified e-tutors. They

provide content related support in case of questions

and misunderstandings, but also offer individual and

group support, technical support, as well as

organisational support.

Design Recommendations for Successful Cross-university Collaborative Group Work: Two Best Practices Cases

241

3.1 Design Measures in Case Two

The following design measures were implemented in

the VCL setting:

Knowledge Acquisition. During the preparation

phase, participating students could access e-lectures

for theoretical knowledge transfer. They were

didactically processed and enriched using the e-

lecture tool "Camtasia". The e-lectures were provided

to the participants before the course, which allowed

them to use time in the real and virtual classroom for

joint discussion and practical application of the

contents provided. The e-lectures supply a

homogeneous basic knowledge among students of

both universities in order to facilitate their entry into

joint group work.

Group Work. In the virtual teamwork phase, the

participants collaborate on a complex, realistic

problem in the form of a case study on the provided

open source platform elgg (https://elgg.org/). The

selection of suitable tools and technical framework

conditions creates the basis for an effective virtual

collaboration between the learners. The necessary

functions for synchronous and asynchronous

communication (e.g. forum, blog, wiki, chat etc.)

were taken into account. The students were free to use

alternative online tools of their choice to complement

the platform. Such external work had to be

protocolled by the students on the platform. The

communicated guiding principle was that only

learning processes that were visible on the platform

can be assessed and evaluated. The focus of the

virtual group work was the solution of tasks with a

close connection to possible company problems and

future professional tasks. The tasks to be solved in the

group work are characterized by open solutions

requiring explanation, which concentrate on gaining

new practical knowledge through discussion and

exchange. The groups composition was arranged by

the course coordinators in order to achieve the highest

possible interdisciplinary mix. To further support the

acquisition of competence, the VCL project is

followed by a phase of individual and group-specific

self-reflection.

Assessment. In the follow-up phase, the focus lies on

the final assessment of the learners. In this context,

not only the contents of the case study solutions were

taken into account, but also observations made during

the VCL project in the sense of a formative

assessment, e.g. on the systematics of the joint

approach, collaboration in the group, commitment

and role conformity of the participants. The

quantitative analysis of the participant’s data traces

generated on the virtual learning platform during the

activity (Learning Analytics) was used to enrich and

objectify these rather subjective assessments.

To support the virtual group work several

interventions have been implemented, e.g.

Role Concept: The orientation towards

different roles for virtual collaboration

promotes the independent organisation and

planning of learning processes as well as the

distribution of tasks between the students

during group work (Bukvova, Gilge, &

Schoop, 2007). Three different roles were

created for this purpose: Team manager,

reporter and members. These roles determine

the function and responsibility of the

participants within the group process. Based on

their self-assessment of individual strengths,

abilities, work and learning experiences, the

participants had to agree democratically on the

distribution of roles. The individual roles are

characterised by the following requirements:

o Team managers: control and

organisation of group work, preparation

of project plans, distribution of tasks,

definition of group deadlines

o Team reporter: preparation of written

documentation (protocols, weekly

reports), publication of interim results

and group results

o Team member: Working on the joint

group solution

Group Contract: Compared to Case 1, the

participants had rather strict guidelines as to

which points should be included in the group

contract. In the Group Contract, the group

members agree on which results they are

aiming for in the course, whether, for example,

they want to achieve the best possible grades or

complete the course with the least effort, they

also agree on common rules of communication,

define the tools to work with, and clarify times

when they are available. The group members

finally sign the contract to be concluded by

consensus and can refer to it in their group

work.

e-Tutors: The e-tutors are master students who

are qualified in a separate one semester course.

The e-tutors were part of the virtual group, but

they were not involved in the creation of the

assignments. They did not provide feedback on

the content of the assignments in sense of right

or wrong. Their main focus was on facilitating

the acquisition of teamwork competencies.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

242

Formative Feedback: As the module focused

on enhancing such teamwork competencies in

addition to human resource knowledge, the

participants received formative feedback from

the e-tutors on their collaboration at group

level. Formative criteria were structuring the

cooperation, team spirit, decision-making

processes and communication among each

other. During their daily work with the

participants, the e-tutors filled an observation

sheet that can be used by the teaching staff to

objectify their formative assessment.

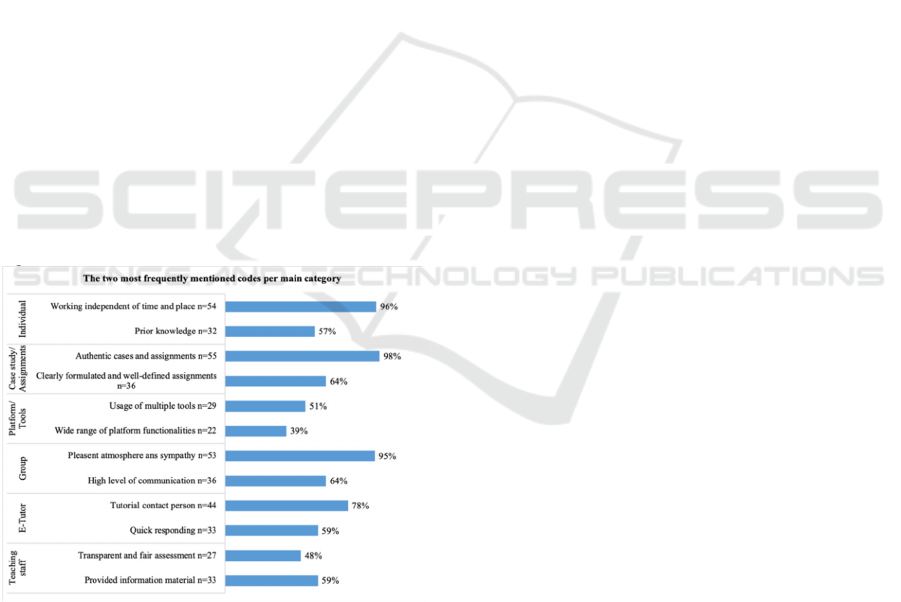

3.2 Evaluation of Case Two

The evaluation consisted of 56 written reflections by

the students, which were inductively analysed with

Mayring's (2014) qualitative content analysis. In total

25 students (64% female) from the winter semester

2017/18 and 31 (77% female) from 2018/2019. The

data was analysed using MAXQDA software. The

analysis of the data material focused on statements

that pinpoint criteria for successful virtual

collaboration from the student's point of view. A total

of 156 criteria were identified in six main categories.

A detailed description of the evaluation can be found

in Dörl, Kurz, & Clauss (2019). In the following, the

presentation of the results focuses on the two most

frequently mentioned codes per main category (see

figure 2).

Figure 2: Evaluation of success factors.

Individual. The vast majority, 54 out of 56 (96%)

students appreciate working independent of time and

place. This enables flexibility for the individual

through individual work and time management for the

independent development of solutions. Bridging

distances and independence from fixed attendance

times facilitates synchronous and asynchronous

communication between group members. This

reduces private conversations and promotes the

efficient use of time resources. For 32 (57%) students,

the prior knowledge of the group members is relevant.

The knowledge should be homogenous enough to

have a mutual understanding for the group work and

as heterogenous as possible to facilitate optimal

discussion possibilities. This includes previously

attended modules, media competence, practical

experience and methodological knowledge from the

studies. Students primarily mention subject-specific

knowledge.

Case Study/Assignments. Authentic case studies and

assignments are a success criterion for 55 (98%) of

the students. Practice-related, realistic situations

create a comprehensible context and a better

understanding of the contents presented in the course.

They also provide an insight into the course of

business processes. For 36 (64%) of the students,

clearly formulated and well-defined assignments are

an important criterion. However, the participants

wish to have less room for interpretation to

understand and solve the tasks independently.

Furthermore, tasks should be designed in such a way

that they can be easily and fairly divided within the

group.

Platform/Tools. From the point of view of 29 (51%)

participants, the usage of multiple tools is particularly

important. This can avoid channel reduction, speed up

response times and facilitate coordination between

group members. Due to the high flexibility, a

purpose- and solution-oriented usage can take place.

For 22 (39%) students it is important to have a wide

range of platform functionalities that facilitate

communication and organisation of the group.

Functions for synchronous and asynchronous

communication should be available, which allows

archiving of the communication processes.

Group. The majority 53 of the 56 (95%) students

consider a pleasant atmosphere and sympathy within

the group to be particularly important. The prevention

of conflicts, understanding of group members and

respectful interaction are particularly often

mentioned as characteristics of a pleasant group

atmosphere. A high level of communication within

the group is also essential for successful

collaboration, 36 (64%) of the 56 students name this

criterion. This includes openness, quick reactions, an

appropriate tone, adequate organisational

arrangements, the active participation of all group

members in discussions as well as the quality of the

answers. Frustration and conflicts can arise from a

lack of communication.

Design Recommendations for Successful Cross-university Collaborative Group Work: Two Best Practices Cases

243

E-Tutor. For 44 (78%) students, a tutorial contact

person is important for questions about problems

which cannot be solved independently or with the

help of the group. They provide confidence. The

groups work-flow is interrupted by the waiting time

for responses. Therefore, 33 (59%) of the students

request quick responding from their tutors to continue

working on the assignments promptly. They should

also provide feedback as quickly as possible and

intervene if tasks do not meet the requirements or if

the achievement of learning objectives is at risk. The

main focus is on content-related feedback.

Teaching Staff. Twenty-seven (48%) students

emphasise the transparent and fair assessment. Group

members should be assessed as objectively as

possible according to their qualitative contribution.

The assessment criteria must be clearly

communicated in order to make the assessment

comprehensible to all participants. Furthermore, 33 of

the 56 (59%) participants consider the provided

information material, such as available e-lectures and

recommended specialist literature, as an important

criterion.

4 FRAMEWORK FOR VCL

With regard to both presented VCL scenarios, design

principles for a successful implementation of virtual

group learning can be postulated, based on best

practices observed by the educators. A distinction is

made between design dimensions on the macro level

and the micro level.

4.1 Macro Level of VCL-planning

The macro level reflects the field of institutional

planning. University collaborations are embedded in

an organizational framework, e.g. study programs,

study modules or courses, whose framework

conditions strongly influence the design of VCL

scenarios. Therefore, the following dimensions for

the conception of VCL scenarios on the macro level

must be analysed.

Curriculum determines how the VCL should

be integrated into the regular study program.

The curricular conditions, especally course

objectives and module descriptions

(qualification objectives, course contents,

ECTS, Workload) must therefore be in

conformity with the planned scenario.

Study groups reflect different cultural

characteristics, with respect to nationalities,

higher education culture and subject culture.

Cultural differences can be understood as a

resource, as they promote diversity, but they

also harbor potential for conflict, if different

demands for the teaching methods collide.

The technology defines the technological

framework with which university

collaborations can be implemented via VCL.

In addition to a good Internet connection,

these include available hardware and

software, as well as the physical nature of

rooms for teaching and/or group work. In

addition to "hard" technical facts, data

protection regulations and privacy

guidelines of all participating universities

are to be examined in order to clarify which

social media tools and analytics tools can be

used and in which form the permission of the

students for the analysis and evaluation of

their data is necessary.

4.2 Micro Level of VCL-planning

The micro level describes the conditions for

successful implementation of VCL scenarios in

pedagogical and organizational terms, by focusing on

the teaching and learning processes.

A basic prerequisite for the success of the cross-

university virtual group work is the accompaniment

by e-tutors. E-tutors are the link between learners and

teachers and are prepared for the specific needs of

online group work. In particular, the availability of

one concrete contact person was emphasised in cross-

university settings. Inconsistent statements and

information asymmetries between lecturers of

participating institutions were intercepted by the e-

tutors as an intermediate level and could be cleared

up before they reached the groups. In addition to the

communicative support, the media-didactic

assistance issued by the e-tutors was appreciated. The

e-tutors gave helpful advices on which online tools

are most suitable for which tasks and were available

in case of technical difficulties. For this reason, the

need for e-tutors should be recognized at an early

stage and recruited and qualified as part of the

preparation process. In addition, it is advisable to

involve the e-tutors directly in the design of the

learning arrangement.

The learning objectives and evaluation criteria of

virtual group work must be defined between the

parties involved and communicated to the students.

Already agreeing on common learning goals is

challenging because courses are usually embedded in

study modules, whose qualification objectives often

differ significantly. The adaptation of module

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

244

descriptions and the examination types specified

therein requires a longer preparation time and are

only possible within certain deadlines. As a result,

cross-university modules may have the same amount

of ECTS credits but require different examination

types as defined in the module description. These

differences are an obstacle, as they were perceived as

unfair within the groups and, in the opinion of the

participants, had a negative impact on the motivation

of the group members. It is recommended that the

examination types are as close as possible to each

other so that a formative assessment is possible for all

involved institutions. The evaluation of group work

must be oriented towards the learning objectives and

thus be consistent and transparent for all participants.

The students have to know the requirements for the

VCL outcome (product) and for the VCL procedure

(process) in advance.

The selection of topic and assignments, which are

relevant and interesting for the students is the core of

VCL scenarios. The topics must be practical, realistic

and realizable, and focused on the future working

field of students. The creation of authentic case

studies (case 2) requires a reorientation of the focus

from scientific work to practice-relevant actions. If a

fictional case company is used (case 2), the company

created should be adapted to the desired output of the

participants. For example, case study companies with

modern, flatter hierarchies are more suitable to

achieve innovative, creative results, while classic,

rigid hierarchies in large companies are more suitable

to generate change management approaches.

The implementation of VCL requires the strong

engagement of the students on different levels. On

one hand, they have to achieve the best possible result

(learning outcome). On the other hand, VCL also

requires strong involvement in the group work

process, for example, by assuming responsibility for

special tasks (e.g. coordination, documentation). The

use of game elements may help strengthen students’

engagements (Fischer & Heinz, 2018; Fischer, Heinz,

Schlenker, Münster, & Köhler, 2016). Within case 1

a scoring system was introduced for the evaluation of

group work, and the project presentation was

embedded in a competitive framework (pitch) in

which the students had to present and explain their

project.

The students have to practice the interaction in

virtual group work to succeed. Assistance and clearly

communicated requirements are just as necessary as

regular fromative feedback. In both VCL projects,

several milestones were defined for students to

submit the interim results of their work and then

receive qualified feedback from the tutors. In case 1,

the primary focus was on providing feedback on the

content, while in case 2, the focus was on the

acquisition of competencies for teamwork.

Learning Analytics facilitate formative feedback.

A meaningful assessment of learning processes and

learning outcomes for virtual settings should be

enhanced by “hard”, fixed, automatically measurable,

quantitative indicators. These can only be analysed on

predefined platforms that offer a gateway to analyse

these data (see case 2). For Learning Analytics

meaningful data on user activities and interactions

with learning content as well as between learners in

the virtual room must be identified, recorded,

processed and made available in an understandable

form based on digital traces relevant to learning

objectives and expected learning outcomes. The

visualization of learning analytics data can help to

improve the overview of the group performance of e-

tutors. This allows to enlarge the e-tutors’ span of

supervision. The analysed data can also be used to

develop gamification elements as ad-hoc feedback for

learners in order to achieve a stronger learner-centred

and automated approach for engagement-enhancing

measures.

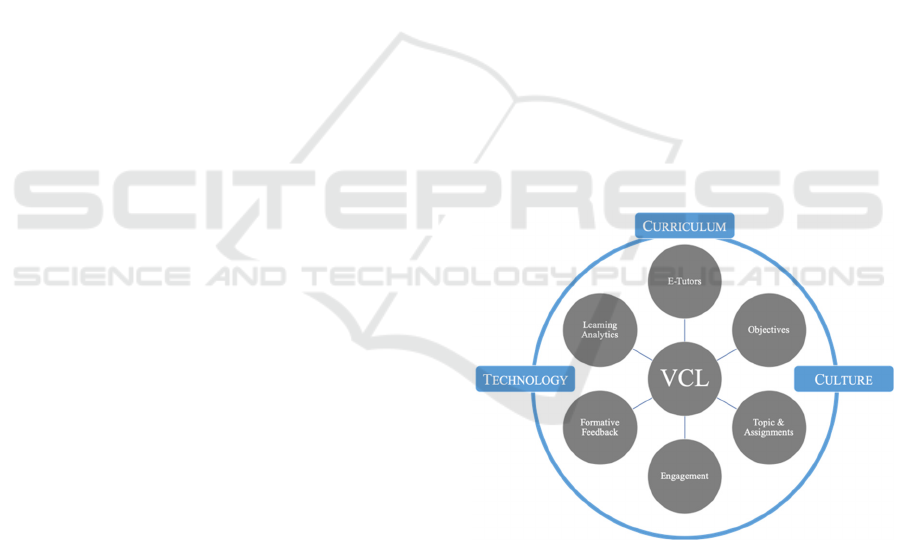

The following framework (see figure 3)

summarizes the design dimensions of the micro and

macro levels.

Figure 3: Design dimensions for the implementation of

VCL-Scenarios.

4.3 Lessons Learned and Design

Recommendations for

VCL-planning

At this point, selected main findings are compiled and

further concrete design measures for the

implementation of cross-university cooperation are

derived.

Design Recommendations for Successful Cross-university Collaborative Group Work: Two Best Practices Cases

245

Consensus Aggregation of Learning Objectives.

When designing learning objectives, different focuses

should be considered in the early planning process of

complex teaching-learning arrangements, especially

in the case of cross-university arrangements. For

example, Universities of Applied Sciences tend to

focus on concrete learning outcomes with a close

practical orientation, while full universities focus on

more abstract, generalised knowledge. In the

planning process and in the process of preparing the

case study, these differences repeatedly became

apparent and were discussed in a consensus-oriented

form. As a compromise, the subtasks of the case study

were each designed in such a way that they showed

increasing degrees of freedom and complexity in the

solution design while applied in practical context.

The cooperative preparation of case studies with

different learning objectives leads to an increased

need for coordination, which has to be considered in

the planning process. Therefore, an early start with

sufficient preparation time is a crucial criterion for

case study design.

Independent Work as Learning Objective. Some of

the participants described personal insecurities due to

the open character of their assignments. Independent

work should be clearly formulated as an assignment

and the development of media competence should be

emphasised as an explicit learning objective. In

addition, methodological e-lectures should be made

available in which the “do’s and don't’s” of project

management as well as assistance for a task-specific

social media tool selection are prepared.

Content Related Feedback. The evaluations revealed

that participants requested feedback on the content of

their work directly after finishing the different

assignments. Since e-tutors do not necessarily have to

have expertise in the respective subject area, detailed

sample solutions should be created. In order to

enhance the feedback quality, the following measures

should be taken:

Extending Support: Support should be

extended by the role of a subject-specific

expert. E-tutors collect content related

questions and pass these on to the subject

experts in regular intervals. To facilitate

coordination, communication channels and

responsibilities should be coordinated in

consensus. An organisational chart should be

generated to clarify the responsibilities for the

individual question types and clarify the

responsibilities of the e-tutors.

Extension of the Sample Solution and

Development of a Content FAQ: Based on

frequently asked questions, a content FAQ

should be created, which could be provided for

future e-tutors. It is also advisable to adapt the

level of detail of sample solutions to the needs

of non-specialists. These steps facilitate faster

response times to content related questions.

(Online) Expert Consultations: In order to offer

content related feedback and the opportunity

for subject-specific questions to the groups

after completion of the respective work

assignments, the subject experts should provide

slots for synchronous (online or in person)

consultations after completion of the respective

assignments.

Evaluation for Further Development. The retrieved

evaluations showed a wide range of suggestions for

further development, especially regarding the

organisation of the cooperation, the case study

material the assignments as well as technical aspects.

The high adaptability and creativity of the

suggestions for improvement in terms of content were

very helpful. Evaluations offer the opportunity to

receive insight to the needs and difficulties of the

students. They are essential for the continuity of

cooperation. They significantly facilitate the

identification of improvement potentials and the best

possible design for improvement. Both quantitative

and qualitative evaluations are an important

component in the design of virtual collaborations. Not

only students, but also e-tutors and the teaching staff

should be involved.

5 CONCLUSION

This article demonstrates the potential of VCL in

cross-university collaboration. On the one hand, the

paper shows how to decrease university boundaries,

on the other hand, how modern collaboration skills,

which are crucial for working in a digital

environment, can be conveyed to students. However,

it also becomes clear that the design of VCL scenarios

is a complex task. The evaluations show design

measures that facilitated successful cross-university

collaborative group work on different levels. On the

macro level the success of such teaching formats

depends on the individual institutional conditions

(curriculum, equipment and culture) of the partners

involved. In addition, successful cross-university

VCL concepts are characterized on the micro level by

the e-tutorial support of the group work, transparent

learning objectives and evaluation criteria, the

selection of relevant, realistic and job related topics

and assignments, the intensive participation of the

learners, formative feedback and learning analytics.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

246

Based on lessons learned during the cross-university

online collaborations concrete design measures for

the implementation of VCL programs are derived.

Concrete design advices for the consensus

aggregation of learning objectives, the

communication of independent work as learning

objective, content related feedback and the evaluation

for further development are presented.

The framework presented as well as the lessons

learned and design recommendations derived from

them can provide targeted support for the planning of

collaborative online blended learning arrangements.

They should be understood as recommendations and

give guidance in the sense of best practices. They

should be flexibly adapted in view of existing

framework conditions.

Especially in the application of learning analytics

and the use of gamification measures there is a clear

research potential. It should be analysed how a

learner-centred support of learning processes and the

engagement of the learners can be supported by

automated analysis of data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In 2017 the cooperation of case 2 „Personalwirtschaft

integrativ und virtuell (LiT PIV)“ as part of the

cooperative project "Teaching Practice in Transfer

plus" was financed by the German Federal Ministry

of Education and Research.

REFERENCES

Aktas, F., Pitts, K., Richards, J. C., & Silova, I. (2017).

Institutionalizing Global Citizenship: A Critical

Analysis of Higher Education Programs and Curricula.

Journal of Studies in International Education, 21(1),

65–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315316669815

Balázs, I. E. (2005). Konzeption von Virtual Collaborative

Learning Projekten: Ein Vorgehen zur systematischen

Entscheidungsfindung. TU Dresden.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom

learning. Assessment in Education, 5(1), 7–474.

Breitenstein, M., Dyrna, J., Heinz, M., Fischer, H., & Heitz,

R. (2018). Identifying Success Factors For Cross-

University Computer-Supported Collaborative

Learning. In IAC in Dresden 2018. Teaching, Learning

and E-learning (IACTLEl 2018) and Management,

Economics and Marketing (IAC-MEM 2018). Dresden.

Bukvova, H., Gilge, S., & Schoop, E. (2007). International

Harmonization of Higher Education Programs - A

Bottom-Up Approach by exchanging mobile european

modules. In M. B. Nunes (Ed.), Computer Science and

Information Systems 2007. Proceedings of the IADIS

International Conference e-Learning 2007. Lisbon,

Portugal.

Carretero, S. ., Vuorikari, R., & Punie, Y. (2017). DigComp

2.1: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens

with eight profi-ciency levels and examples of use.

https://doi.org/10.2760/38842

Cowie, B., & Bell, B. (1999). A Model of Formative

Assessment in Science Education. Assessment in

Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 6(1), 101–

116. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695949993026

Dillenbourg, P. (1999). What do you mean by ’

collaborative learning ’? Collaborative Learning

Cognitive and Computational Approaches, 1(6), 1–15.

Dörl, M., Kurz, J., & Clauss, A. (2019). Kritischer

Perspektivenwechsel im virtuellen Klassenzimmer -

Charakteristika einer erfolgreichen virtuellen

Zusammenarbeit aus Studierendensicht. In T. Köhler,

E. Schoop, & N. Kahnwald (Eds.),

Wissensgemeinschaften in Wirtschaft, Wissenschaft

und öffentlicher Verwaltung. 22. Workshop

GeNeMe‘19 Gemeinschaften in Neuen Medien (2019)

(pp. 158–166). Dresden.

Erdoğan, A. (2015). Current and future prospects for the

Bologna Process in the Turkish higher education

system. In The European Higher Education Area (pp.

743–761). Springer, Cham.

Fadel, C. (2008). 21st Century Skills: How can you prepare

students for the new Global Economy. Retrieved

December 19, 2019, from https://www.oecd.org/site/

educeri21st/40756908.pdf

Fisch, K., & McLeod, S. (2007). Did You Know; Shift

Happens. Retrieved December 19, 2019, from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljbI-363A2Q

Fischer, H., & Heinz, M. (2018). Gamification of Learning

Management Systems and User Types in Higher

Education. In M. Ciussi (Ed.), 12th European

Conference on Games Based Learning (pp. 91–98).

Sophia Antipolis, France: ACPI.

Fischer, H., Heinz, M., Schlenker, L., Münster, S., &

Köhler, T. (2016). Gamification in der Hochschullehre

– Potenziale und Herausforderungen. In S. Strahringer

& C. Leyh (Eds.), Serious Games und Gamification -

Grundlagen, Vorgehen und Anwendungen (pp. 113–

125). Springer.

Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning:

Uncovering its transformative potential in higher

education. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(2),

95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001

Goodyear, P., Jones, C., & Thompson, K. (2014).

Computer-supported collaborative learning:

Instructional approaches, group processes and

educational designs. In Handbook of research on

educational communications and technology (pp. 439–

451). Springer.

Gross, R. (2015). Psychology: The science of mind and

behaviour 7th edition. Hodder Education.

Gunderson, S., Roberts, J., & Scanland, K. (2004). The jobs

revolution: Changing how America works. Copywriters

Incorporated.

Design Recommendations for Successful Cross-university Collaborative Group Work: Two Best Practices Cases

247

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800

meta-analyses relating to achievement. routledge.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1987). Learning

together and alone: Cooperative, competitive, and

individualistic learning. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Kay, J., Reimann, P., & Diebold, E. (2007). Visualisations

for team learning: small teams working on long-term

projects. In Proceedings of the 8th iternational

conference on Computer supported collaborative

learning (pp. 354–356). International Society of the

Learning Sciences.

Lönnblad, J., & Vartiainen, M. (2012). Future

competences–competences for new ways of working.

Publication Series B, 12.

Lu, J., Lajoie, S. P., & Wiseman, J. (2010). Scaffolding

problem-based learning with CSCL tools. International

Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative

Learning, 5(3), 283–298.

Marttunen, M., & Laurinen, L. (2001). Learning of

argumentation skills in networked and face-to-face

environments. Instructional Science, 29(2), 127–153.

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis:

theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software

solution. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-

3709(07)11003-7

OECD. (2018). The future of education and skills:

Education 2030. (Organisation for Economic

Cooperation and Development, Ed.). Paris, France:

Directorate for Education and Skills, OECD.

Perez-Sabater, C., Montero-Fleta, B., MacDonald, P., &

Garcia-Carbonell, A. (2015). Modernizing Education:

The challenge of the European project CoMoViWo.

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences,

197(February), 1647–1652. https://doi.org/10.1016/

j.sbspro.2015.07.214

Pisoni, G., Marchese, M., & Renouard, F. (2019). No Title.

In 2019 IEEE Global Engineering Education

Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 1017–1102). IEEE.

Rietze, M. (2019). eCollaboration in der Hochschullehre –

Bewertung mittels Learning Analytics. TU Dresden.

Rovai, A. P., & Downey, J. R. (2010). Why some distance

education programs fail while others succeed in a global

environment. The Internet and Higher Education,

13(3), 141–147.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2006). Knowledge

building: Theory, pedagogy, and technology. na.

Scriven, M. (1967). The Methodology of Evaluation. In R.

Tyler, R. Gagne, & M. Scriven (Eds.), Perspectives of

Curriculum Evaluation. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Seuferth, S., & Mayr, P. (2002). Fachlexikon e-Learning.

Wegweiser durch das e-Vokabular. Bonn:

ManagerSeminare.

Simm, D., & Marvell, A. (2017). Creating global students:

opportunities, challenges and experiences of

internationalizing the Geography curriculum in Higher

Education. Introduction.

Journal of Geography in

Higher Education, 41(4), 467–474.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2017.1373332

Slavin, R. (1990). E. 1995 Cooperative learning theory

research, and practice. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Suthers, D. D., & Hundhausen, C. D. (2003). An

experimental study of the effects of representational

guidance on collaborative learning processes. The

Journal of the Learning Sciences, 12(2), 183–218.

Tawileh, W. (2017). Design Principles for International

Virtual Collaborative Learning Environments Based on

Cases from Jordan and Palestine. TU Dresden.

Tawileh, W., Bukvova, H., & Schoop, E. (2013). Virtual

Collaborative Learning: Opportunities and Challenges

of Web 2.0-based e-Learning Arrangements for

Developing Countries. In N. A. Azab (Ed.), Cases on

Web 2.0 in Developing Countries: Studies on

Implementation, Application, and Use (pp. 380–410).

Hershey, PA: IGI Global Information Science

Reference.

Trilling, B., & Fadel, C. (2009). 21st Century Skills.:

Learning for Life in Our Times. John Wiley & Sons.

Vuorikari, R., Punie, Y., Carretero Gomez, S., & Van den

Brande, G. (2016). DigComp 2.0: The Digital

Competence Framework for Citizens. Update Phase 1:

The Conceptual Reference Model. Luxembourg:

Publication Office of the European Union.

https://doi.org/10.2791/11517

Webb, N., & Palincsar, A.-M. (1996). Group processes in

the classroom. In D. Berliner & R. Calfee (Eds.),

Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 841–873).

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

248