Evaluating the Learning Process: The “ThimelEdu”

Educational Game Case Study

Stamatios Papadakis

1a

, Apostolos Marios Trampas

2

, Anastasios Kristofer Barianos

2

,

Michail Kalogiannakis

1b

and Nikolas Vidakis

2c

1

Department of Preschool Education, Faculty of Education, University of Crete, Greece,

2

Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Heraklion, Crete, Greece

mkalogian@uoc.gr, nv@hmu.gr

Keywords: Game-based Learning, Serious Games, eLearning, Learning Process, ThimelEdu.

Abstract: Digital games are an important part of most adolescent’s leisure lives nowadays and are expected to become

the predominant form of popular culture interaction in our society. Many educators see digital games as

powerful motivating digital environments, due to their potential to enhance student engagement and

motivation in learning, as well as an effective way to create socially interactive, constructivist learning

environments and educational processes based on each learner’s needs. The present work focuses on how

students acquire knowledge about the subject of the Greek ancient theatre through an interactive 3D serious

game, compared with the traditional teaching process.

1 INTRODUCTION

Our century is characterized by the continuous

growth of technology and integration of new and

robust technological achievements in our everyday

lives (Kalogiannakis & Papadakis, 2019). From

health and science, to houses, people are using

technology and computers for progressively simpler

tasks. These robust changes have affected education

and the way educational process happens,

dramatically changing the view of traditional

teaching classes.

Over the last years, an increasing demand for

serious games has developed. Educational systems

around the world, have transformed their processes,

adopting the game-based learning model (Vidakis et

al., 2019; Vidakis, Barianos, Xanthopoulos &

Stamatakis, 2018). As part of the educational use of

ICT, digital games become learning tools, motivators

and generators of curiosity and as a result an effective

means of optimizing student learning and

performance in daily educational practice (Papadakis,

2018).

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3184-1147

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9124-2245

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0726-8627

Researches have concluded that educational

material that is presented through interactive games,

increases learner’s engagement and awareness for the

educational process itself (Kalogiannakis, Nirgianaki

& Papadakis, 2018). It is less possible for a student to

renounce an educational process that motivates him.

For instance, a primary school learner is more excited

to learn historical events through a virtual

environment with amusing graphics, animations and

multimedia, rather than paying attention on the

traditional classroom’s blackboard or reading from

his textbook.

Additionally, as digital games are an important

part of most adolescent’s leisure lives nowadays, they

are expected to become the predominant form of

popular culture interaction in our society. Many

educators see digital games as powerfully motivating

digital environments because of their potential to

enhance student engagement and motivation in

learning, as well as an effective way to create socially

interactive and constructivist learning environments

(Papadakis & Kalogiannakis, 2018).

The development of serious games that present

educational material, can also help educators to create

290

Papadakis, S., Trampas, A., Bar ianos, A., Kalogiannakis, M. and Vidakis, N.

Evaluating the Learning Process: The “ThimelEdu” Educational Game Case Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0009379902900298

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 2, pages 290-298

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

motivating, in and out of class, educational and

assessing processes and therefore change old-

fashioned exams and tests procedures. Furthermore,

the evolution of portable devices has made it possible

for learners to be part of an educational process from

their homes, libraries and other study or leisure

locations.

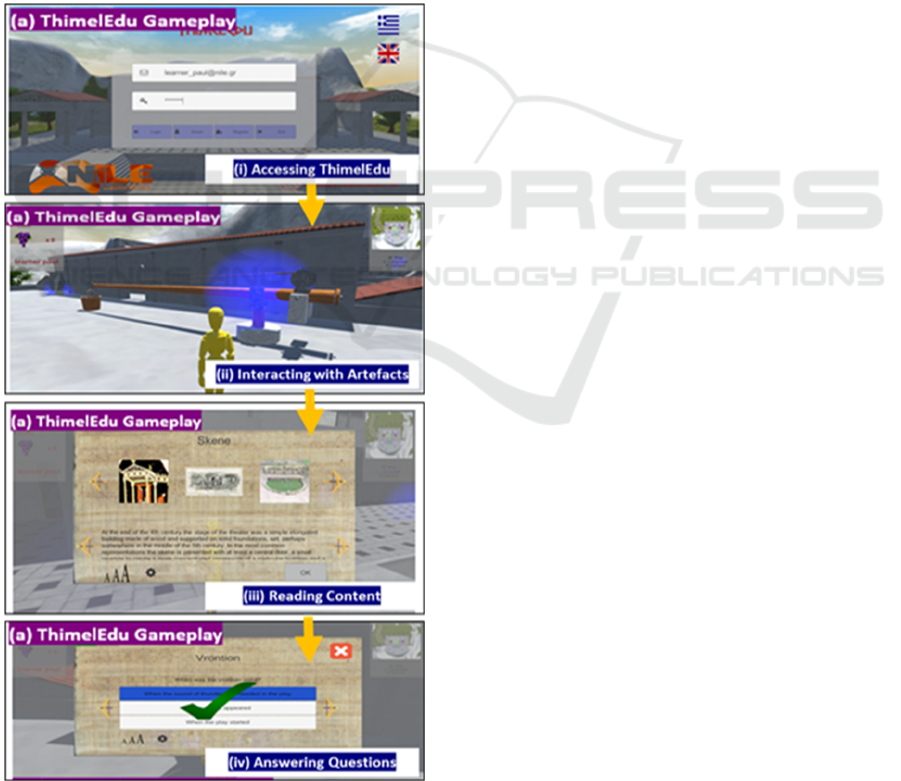

Our work focuses on the use of a serious game in

a school class and its impact on student’s knowledge

compared to traditional teaching procedures. Students

were asked to play a 3D interactive serious game

called “ThimelEdu” (Vidakis et al., 2018; 2019).

Through interaction with the 3D environment and its

objects, students were taught about the Greek ancient

theater. The educational material is presented through

text, videos, questionnaires and images while

students can navigate through the material using a 3D

environment.

The rest of the paper is structured in the following

sections: (a) background work presenting basic

features about game-based learning and serious

games, their results on the educational process and

therefore on how students acquire knowledge, (b) an

experiment where the traditional educational

procedure is compared to the game- based learning

model for the subject of the Greek ancient theater and

its findings, (c) .

2 BACKGROUND

There is a growing appreciation that the conventional

approach to the process of teaching does not address

the social, emotional, mental and motivational needs

of the new generation (Papadakis, 2018). The robust

and continuous growth of technology has made

students willing to use different technologies in

ordinary usage. As Prensky mentioned, today’s kids

belong to the category of digital natives, comfortable

with the digital age (Prensky, 2001a). In this

perspective, the Information and Communication

Technologies (ICT) are nowadays a trend in the field

of education. The use of computer systems, computer

applications, and ever more smart devices like

smartphones and tablets during the learning process,

has institute new standards in the way that students

acquire and retrieve knowledge. As Prensky stated,

students nowadays have developed assorted

perspectives, in relation with non-computerized age

students, and thus educational process needs to adjust

to the requirements of this digital age (Prensky,

2001a; 2001b). Especially, the popularity of gaming

in the dominant culture of the new generation has

spurred the interest of the educational community,

with several educators and researchers seeking

different approaches for using digital games in the

classroom environment (Kalogiannakis & Papadakis,

2019).

Under those circumstances, the field of eLearning

achieves traction and improvement day by day. The

rationality, as well as the functionality of eLearning

environments, has made it possible for teachers to

provide and deliver knowledge and educational

content to students across the globe, addressing the

problems of distance and time (Gaur, 2018). The

learning process through an eLearning environment

can be achieved either synchronously, where the

educational material is delivered in real time and

educators and students can interact with each other,

or asynchronously where there is no need for

educators and students to be online at the same time

and the material is stored and always accessible

(Hrastinksi, 2008).

However, classic eLearning environments have

shown their own issues. Lack of awareness and

boredom has been observed through monitoring of

students during an educational process with a

classical eLearning module (Erhel & Jamet, 2013).

The information overload, the lack of practice

opportunities, as well as the lack of motivation

present at sometimes, are some of the reasons that a

student can easily and quickly fall behind in an online

educational process. There is a point where the field

of “Game based learning”, can oversee this above-

mentioned obstacle and provide an immersive

learning experience in a virtual environment where

learners can acquire knowledge in a recreative way.

2.1 Game-based Learning

Over time, educators concluded that repeated or

periodical exams do not successfully evaluate a

learner’s grip of a subject and its application. Digital

games are gaining wide recognition as an effective

way to create socially interactive and constructivist

learning environments (Papadakis, 2018). Alternative

teaching methods, like serious games and virtual

worlds, are trying to replace the existing conventional

teaching processes. This is a shift that is going on at

an enduring pace over the past years. For the

eLearning environments, there are needs of

significant changes and they must be capable to

provide new features, in order to keep learners fully

engaged with the educational process. One of those

features is the digital game - based learning, able to

deliver educational material through interactive

games through increased entertaining as well as

relaxing methods (Prensky, 2001b).

Evaluating the Learning Process: The “ThimelEdu” Educational Game Case Study

291

In order to define an educational activity as a

game, Teed & Manduca (2004) proposed the

following:

a) Competition: Each game is consisted of some

essential characteristics. One of them is the

scoring. Players/learners are trying to complete

tasks in order to gain score and therefore are

inspired to upgrade their performance.

Moreover, through games, learners cooperate to

complete tasks that rise through gameplay.

b) Engagement: The gameplay’s graphics,

animations, music together with the appropriate

storytelling, makes learners / players engaged

with the game and excited. Thus, it is less likely

to give up until the whole game is over.

c) Rewarding: Players and therefore learners get

energized when a game rewards them with points

for completing a task.

Based upon those motives, game-based learning

utilizes the use of game mechanisms, in the context

of non-game concepts. Students can easily engage

with gaming environments, that combine multimedia

with different educational materials. Moreover, they

can revise educational material by playing a specific

part of the game multiple times. The concept of game-

based learning was developed with the philosophy of

providing the educational material through an

entertaining and relaxing game, so students can

acquire knowledge, retrieve it and manipulate it in an

appropriate way to solve real world problems

(Mouaheb, Fahli, Moussetad & Eljamali, 2012).

Comparing traditional with game-based learning,

it is clearly noticeable that (a) students’ awareness for

the subject, (b) the ways that acquire knowledge and

apply the subject in the real world are elevated with

game-based learning approach and that game-based

learning heads off a new era beyond the traditional

learning.

Table 1 Comparison between traditional and game-based

learning (Jaypuriya, 2016).

Traditional

Learning

Game-

Based

Learning

Cos

t

Low

p

h

y

sical liabilit

y

Traditional assessmen

t

Deepl

y

en

g

a

g

emen

t

Apply knowledge in real

worl

d

p

roblems

Feedbac

k

and response

Knowledge acquisition is

b

ased on the learne

r

itself

Learners are willing to learn more and more if the

material is presented in an exciting and interactive

manner instead of traditional paper and white board

ways. Moreover, playing educational games cannot

take place only inside the classroom but learning

sessions can move outside the classroom as well.

Learners can play games anywhere desired without

spatial boundaries. Nowadays, with the rise of smart

devices, cloud computing and game technology, the

development of classrooms and learning sessions

outside traditional classes is an easy task. Games have

incorporated, traditional and innovative assessment

procedures while learners are engaged in assessment

before, during and after the learning session with the

educational game.

2.2 Serious Games

As discussed so far, there is a need for developing

classes that deliver the educational context through

interactive games, on which the whole educational

process will be based. Those games are called serious

games. By definition, serious games are educational

interactive games with primary objective to educate

and train and secondly to entertain (Vidakis,

Syntychakis, Kalafatis, Christinaki & Triantafyllidis,

2015). Industries such as military, health, science,

education and even politics, are using serious games

as the origin of their instructive process. Since this

work is discussing the computerized age, we will

limit our thoughts to the field of “Digital serious

games” in education.

As stated before, game-based learning makes

learners engaged in the educational process and

increases their interest and curiosity about the

educational material. Serious games provide an

interactive environment, consisting of graphics,

multimedia, actions, animations, sounds etc.,

visualizing the educational content in an exciting and

amusing way, rather than the traditional black board

in the classroom (Vidakis et al., 2018). By those

means, the term “Edutainment” has come up.

Edutainment uses principles to link education and

learning with entertainment, changing the classical

nature of the educational process.

Games’ industry nowadays is growing and

provides multiple devices capable for playing games.

From computers, to game consoles like PlayStation

or Xbox, to smart devices, like smartphones and

tablets (Vidakis et al., 2019). In the field of

education, it is easier for learners to be part of an

educational process based on a serious game, since

they are, as Prensky stated, digital natives, as they

have easy access on plenty of the mentioned devices

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

292

(Prensky 2001a; 2001b). Also, the fact that today’s

learners have grown up in a digital and computerized

era makes them familiar with different aspects of

technology and capable to use them fluently.

Serious games consist of five fundamental

elements (Mautone, 2008):

Element-A) Structure and Rules. Game’s structure,

rules and boundaries, allow learners to

face the consequences for adhering to

them. Factors like directions,

interactions, activities, rewards and

penalties, configure an environment that

provides different possible solutions for

different goals.

Element-B) Gamification: Scoring, feedback given

to learners for their pace to reach a goal.

It varies from a straightforward

affirmation that a specific activity or

decision was correct, to information

about what learners need to improve.

Element-C) Tasks and challenges: Different possible

difficulties that learners have to face in

order to complete a task and reach the

required goal. Thus, learners are

motivated to improve their skills and

even more compete with other learners.

Element-D) Instructional Support: Assists learners

how to gain knowledge from the game,

practice and what the learning outcomes

will be.

Element-E) Aesthetics: Visuals, graphics,

animations, storytelling, role-playing

and imaginary stories, excite and engage

learners with the educational material.

However, for serious games to have an added value

on the educational process, they must be coupled with

an instructional strategy that engages, explores,

explains, elaborates and evaluates (Hirumi &

Stapleton, 2009).

Serious games can deliver knowledge via an

amusing environment. Their components enable

learners to interact with the educational material and

gain or augment existing knowledge. The whole

educational process has turned from teacher based to

student based, where students are trying to acquaint

with a subject by their own perspectives.

2.3 Cultural Heritage Serious Games

In the present work, we focused on the cultural

heritage serious games, and more specifically for the

Greek ancient theater and the impact that it has in

students gaining of new knowledge. Places of cultural

heritage are presented to the audience through virtual

worlds and tours, for instance a museum’s virtual

tour. Based on this, serious games are able to engage

audience with the virtual material and the educational

content in an amusing way (Vidakis et al., 2018).

Through the years, serious games have been

developed for and supported mainly by places like

schools, museums and archaeological places, with the

purpose to educate students about cultural heritage.

2.3.1 Games and Tools

eShadow: A 2D collaborative platform that allows

users to use tools in order to create, watch, share

shadow theater plays. Users can also import their own

puppets instead of using the existing ones.

MUBIL: This project aims to deliver, and present

knowledge and content stored in the ancient

assortment in the Norwegian Science and Technology

University, where player is an ancient alchemy

apprentice with a goal to produce a certain medicine.

La Dama Boba Game: Player is an actor and

through puzzles and conversations re-produces the

play “La Dama Boba, El juego”.

Acropolis virtual tour: Developed as a web

application that allows users to explore the

archaeological site of Acropolis in Athens.

The Ancient Theatre: A web site that contains

educational games for students and teachers about the

ancient theatre and its god Dionysus. It contains the

games: (a) “what is hidden under the city?” about the

excavation and rebuild of the Larisa’s ancient theater,

(b) “the celebration of the great Dionysia”, where

users are part of a tour in ancient Athens during the

Great Dionysia and (c) “A modern troupe in the

ancient theaters of the world”, where users can search

around the globe for ancient theaters that being used

till now.

2.3.2 ThimelEdu

In this work primary school students have explored

and interacted with educational material about the

ancient theater, through a 3D serious game,

developed with Unity 3D game engine, called

ThimelEdu (Vidakis et al., 2018). The nature of the

theater studies is a challenge for the educators,

because there is a difficulty in recreating situations

and environments. Visits on sites can be difficult and

sometimes impossible for students and the plays can

be disinteresting to learners. Under those

circumstances the ThimelEdu serious game was

inspired and developed.

The main purpose of the game is to deliver

educational content about the Greek ancient theater to

students, as well as to be a complementary tool for the

Evaluating the Learning Process: The “ThimelEdu” Educational Game Case Study

293

educators who seek alternative teaching ways

(Vidakis et al., 2019). The game is consisted of a 3D

environment of an ancient theater where learners can

navigate and discover building and tools used.

Students cruise through and interact with the multiple

scattered artifacts inside the site. The educational

material is presented through texts, images and

quizzes. Assessment is achieved through the possible

questions presented during the navigation and

interaction with the artifacts (Vidakis et al., 2019).

Gamification characteristics, like score and rewards,

are used to enhance players awareness and

performance (Vidakis et al., 2018). Also, the game

provides full accessibility by adapting its content and

the game experiences, according to each learner’s

profile on the IOLAOS platform, ensuring the most

ideal learning conditions for every learner (Vidakis et

al., 2015).

Figure 1: ThimelEdu serious game (Vidakis et al., 2019).

3 OUR APPROACH

The purpose of the present study was to examine

whether a game-based approach contributes to the

development of students’ knowledge compared to the

‘traditional’ teaching approach. A co-examination of

the effect of additional factors, such as gender and

age, was conducted while assessing the impact of the

two forms of teaching intervention on the

development of students ‘knowledge according the

ancient theater. We sought to examine the following

hypotheses:

H1) The initial knowledge of the two groups will

increase significantly after the intervention.

H2) The knowledge of students taught ancient theater

elements with the ‘traditional’ approach is

significantly less than the knowledge of students

taught ancient theater elements with a game and

is not affected by factors such as gender.

4 METHODOLOGY

4.1 Sample

After obtaining central office permission to conduct

this study in school districts in the region of Crete, we

contacted principals as per our institutional review

board protocol to describe the study and request

permission to meet with early childhood educators to

explain the study and determine their interest in

participating. The study adhered to university ethical

guidelines. A common framework of ethical

principles was adopted across the teaching

intervention. Ethical principles relating to basic

individual safety requirements were met regarding

information, informed consent, confidentially and the

use of data.

The research sample was ethnically and language

homogenous and consisted of 22 students (8 boys, 14

girls) from the city of Heraklion, prefecture of Crete,

Greece. The age of the student ranged between 17 and

17.5 years (M = 210 months, SD = 4.7 months, at the

first time of measurement). The student attended two

classes in a public High School during the 2018-2019

school year. Requirements concerning information,

informed consent, confidentiality and usage of data

were carefully met, both orally and in writing, by

informing the school staff, students and parents on the

purpose of the study and their rights to refrain from

participation. Only children who completed all two

rounds of testing (pretest, posttest) were included in

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

294

the final experimental sample. Students were

randomly assigned to one of two groups.

4.2 Data Collection Instruments

For the evaluation of student’s performance before

and after the teaching intervention, a questionnaire

was specially administered for the purpose of the

current study. In short, the concepts examined by the

questionnaire are identifying parts of the ancient

theatre, understanding ancient theatre architecture,

the role of orchestra, etc. Each of these elements is

represented by a set of questions distributed across

the test.

4.3 Research Design – Procedure

For the verification of the research hypotheses, an

experimental procedure was designed, in which the

sample was divided into two groups, the control

group and the experimental group. The experimental

design included three phases:

a) the pre-experimental control phase, during which

the measurement of the dependent variable was

performed,

b) the experimental phase/intervention, during

which manipulation of the independent variable

took place and

c) the post-experimental control phase, during

which post-control of the dependent variable was

performed.

The research procedure consisted of two stages.

The first stage, from September to December of 2018,

involved the pilot test of the game and the creation –

evaluation of the questionnaire. The second stage,

from January 2019 until May 2019, included the pre

experimental procedure, the experimental

intervention and post-experimental procedure.

Student’s regular mathematics classroom instruction

was not interrupted by the study. In the experimental

group, a computer game was used to enhance the

regular classroom instruction, whereas in the control

group the instruction was enriched with the use of

WebQuest.

4.4 Students Pre-test

The first phase, which was common for the two

groups, took place during January and February of the

2018-2019 school year. In this phase, students were

asked to tackle the questions of the questionnaire. The

evaluation lasted for 10 to 30 minutes, depending on

the performance of each student. Students who were

absent on the days the tests were administered were

not included in the sample.

4.5 Teaching Intervention

The teaching intervention took place between January

and April of the 2018- 2019 school year. It aimed to

develop student’s general knowledge about ancient

theater in general. The teaching intervention was

done by the same teacher in both groups in

accordance with the thematic approach, as defined by

the Greek Curriculum of Studies for Secondary

Education. In the control group, the teaching

intervention was enhanced by using the web for a

structured research (WebQuest), whereas in the

experimental group it was enriched by using a special

created computer game. Students who were absent for

more than two teaching interventions were excluded

from the survey. The second phase of the research

was completed by the end of the teaching

intervention.

4.6 Students Post-test

The third and final phase of the research was carried

out in May of the 2018-2019 school year. During this

phase, each student was examined once again in the

questionnaire. For the proper conduct of the test, the

same examination procedure as the one in the pre-test

phase was followed.

5 RESULTS

Prior to data analysis, we ensured the typical

assumptions of a parametric test such as normality,

homogeneity of variances, linearity and

independence were met before various parametric

statistical tests can be properly used. The data were

analyzed using IBM SPSS 23.0 software, and the

significance level adopted was 5% (p < .05).

5.1 Equivalence Checking of the

Experimental Groups

Initially, the equivalence of the two groups in terms

of the student’s gender was tested. The results, after

applying the Chi-Square statistical criterion, showed

that the two groups did not differ significantly in the

number of boys and girls included, χ2(1) = 0.79, p >

0.05. Subsequently, the equivalence of the two groups

in terms of the student’s age was tested. An analysis

of variance showed that the two groups were

equivalent as to student's age, F(1, 20) = 0.1, p > 0.05.

Evaluating the Learning Process: The “ThimelEdu” Educational Game Case Study

295

The one-way ANOVA was also used to investigate

the equivalence of the two groups in terms of the

average score in the questions, which describes the

knowledge of the sample. According to the results of

the ANOVA analysis, the two groups did not reveal a

statistically significant difference in terms of the

performance of student on the questionnaire before

the start of the teaching intervention, F(1, 20) = 0.3, p

> 0.05. Taking into consideration the aggregated

results concerning the formation of the research

teams, we conclude that both groups are equivalent in

terms of: (a) age, (b) gender and (c) knowledge.

6 INFLUENCE OF THE

EXPERIMENTAL

INTERVENTION IN THE

DEVELOPMENT OF ANCIENT

THEATRE KNOWLEDGE OF

STUDENT

6.1 Direct Effects of the Experimental

Intervention in the Knowledge of

Student

The main purpose of this study was to investigate

whether student’s performance in ancient theatre

knowledge increased significantly, as recorded by

their performance in the questionnaire, after teaching

using a special designed game running on computers.

For this purpose, both groups were compared as to

their ancient theatre knowledge in the special created

questionnaire before and after the experimental

intervention, using dependent (paired samples) t-test.

As the results presented in Table 1 reveal, the

knowledge of both groups increased after the

experimental intervention. The difference in the

performance of students in each group during the two

measurements is statistically significant.

To further investigate the first aim of the research

it was considered useful to investigate whether these

two groups differ on a statistically significant level

with respect to the influence of the experimental

interventions. For this reason, ANOVA analysis was

conducted to investigate whether the groups differ on

a statistically significant level. Specifically, the

results of ANOVA showed a statistically significant

difference in student’s final performance in the

questionnaire between groups, F(1, 20) = 11.73, p =

0.0000. Moreover, the mean of the improvement in

the performance of the students in the experimental

group (21.45) is significantly higher than the mean of

the performance of the control group (15.00).

Table 2: Results of the analysis of the t-test per group.

M SD t-test (df=10)

Game based

approach

Knowledge

Pre-

tes

t

9.64 2.84 -7.49, p=0.000

Post-

test

21.45 4.44

M SD t-test (df=10)

Traditional

approach

Knowledge

Pre-

tes

t

9.91 4.85 -6.34, p=0.000

Post-

test

15.00 4.41

6.2 Effect of Other Factors on the

Development of Student’s

Knowledge

A key question in this study was whether the effect of

the experimental intervention on the performance of

the student in ancient theatre knowledge is affected

by other factors. For the investigation of this research

question a test of the degree of interdependence

between the independent variables was conducted by

using the Pearson product-moment correlation

coefficient. The results indicated that there is no

correlation between the age of student and the

improvement of their performance in ancient theatre

knowledge, r(22) = -.014, p > 0.05. Respectively, to

investigate the effect of the gender of the student as a

differentiating factor in the extent of improvement on

performance in ancient theatre knowledge, a t-test for

independent samples was applied. The results of the

test showed that the effect of gender on the

improvement in the performance of student’s

knowledge was not statistically significant, t(20) = -

0.37, p > 0.05, namely, gender does not seem to

influence in any way the improvement of student’s

performance in ancient theatre knowledge.

Additionally, there was a study of the effects of

more than one independent variable on the dependent

variable, namely the improvement in the performance

of student’s knowledge and the interactions between

them. Initially, the main effects of the experimental

intervention and student’s gender on the

improvement in their performance was examined

through the criterion of factorial variance analysis.

The results showed that the interaction between

gender and the experimental intervention had no

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

296

effect F(1, 18) = 0.91, p > 0.05. Additionally, the

main effects of the experimental intervention and the

age of students on improving their performance were

examined. The results from the application of the

criterion showed that the interaction between the age

and the experimental intervention had no effect F(4,

9) = 11.75, p > 0.05.

7 INVESTIGATION OF

RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

The first hypothesis (H1) predicted that the initial

performance in ancient theater knowledge of the

experimental group and the control group would

increase significantly after the intervention.

Statistical analysis showed that both forms of

intervention contributed significantly to the

improvement of student’s performance. As a result,

the first hypothesis (H1), which refers to the positive

impact of both forms of intervention on the

improvement of student’s ancient theatre knowledge

was verified. The second hypothesis (H2) predicted

that the performance of the experimental group and

the control group in ancient theater knowledge would

differ significantly after the intervention, depending

on each form of intervention (game-based approach

or WebQuest). In the intervention, where teaching

with the use of a game was applied, student showed a

higher final performance and a significantly greater

improvement in their knowledge after the

intervention compared to the control group. The

above findings support the second hypothesis (H2).

The third hypothesis (H3) predicted that the

performance of the experimental group and the

control group in ancient theater knowledge would

differ significantly after the intervention, depending

on the use of different forms of teaching intervention,

even after the control of various other factors related

to the development of their knowledge. The

investigation of the interdependence of the

independent variables on the extent of the

improvement in student’s final performance in

ancient theatre knowledge showed that there is no

correlation between age and gender on the extent of

improvement in student’s final performance.

Additionally, investigating the main effects, as well

as the interactions, of more than one independent

variable on the extent of student’s improved

performance in ancient theatre knowledge showed

that the effect of the experimental intervention did not

differ depending on age or gender. Based on these

results, the H3 hypothesis of this study was verified.

8 DISCUSSION

Many educators see digital games as powerfully

motivating digital environments because of their

potential to enhance student engagement and

motivation in learning as well as an effective way to

create socially interactive and constructivist learning

environments (Kalogiannakis & Papadakis, 2019).

The results of this study provide a framework for the

formulation of pedagogical proposals which could

develop students’ knowledge in various disciplines in

secondary education. Of course, technology is not a

panacea. It is not the hardware or the software, but the

combined use of ICT with the pedagogical approach

that has the potential to make a significant

contribution to student's specific knowledge

achievement.

9 CONCLUSION & FUTURE

WORK

To conclude, game-based learning is willing to create

educational processes able to motivate learners and

transform the traditional educational process to an

effective and excited and entertaining procedure

where learners interact directly with the teaching

material (Mawas, Truchly, Podhradský & Muntean,

2019; Dorouka, Papadakis, & Kalogiannakis, 2020).

Serious games are able to increase student’s

awareness about the teaching procedure and

effectively transform knowledge (Papadakis, 2020;

Rosli, Mangshor, Sabri, & Ibrahim, 2017). In the

present work secondary school students taught about

the Greek ancient theater through an interactive 3D

serious game called “ThimelEdu”. An experiment

was held in order to examine if students acquire

knowledge through a serious game, compared with

the traditional learning method.

However, there were limitations on this study that

need to be addressed in future studies. The duration

of the teaching intervention was 13 weeks. Although

it is adequate to test experimentally the effect of the

different didactic approaches, it is not enough to

fulfill student’s needs in the development of their

knowledge to a significantly greater extent. For this

reason, it is necessary to implement a teaching

intervention which will be long enough in duration to

extensively investigate the effect of various didactic

approaches in the development of students’

knowledge. The second limitation of this research is

that the study did not implement a delayed post-test

Evaluating the Learning Process: The “ThimelEdu” Educational Game Case Study

297

to measure whether knowledge gained from a game

or WebQuest assisted learning approach persisted.

Finally, the implementation of a longitudinal

study investigating the effects of different didactic

approaches in the development of students’

knowledge would also constitute a significant

extension of the present study.

REFERENCES

Dorouka, P., Papadakis, St. & Kalogiannakis, M. (2020).

Tablets & apps for promoting Robotics, Mathematics,

STEM Education and Literacy in Early Childhood

Education. International Journal of Mobile Learning

and Organisation, 14(2), 255-274.

El Mawas, N., Truchly, P., Podhradský, P., & Muntean, C.

(2019, May). The effect of educational game on

children learning experience in a slovakian school.,

CSEDU - 7th International Conference on Computer

Supported Education, May 2019, Heraklion, Greece.

Erhel, S., & Jamet, E. (2013). Digital game-based learning:

Impact of instructions and feedback on motivation and

learning effectiveness. Computers & education, 67,

156-167.

Gaur, P. (2018). Research Trends in E-Learning. Media

Communique, 1(1), 29-41.

Hirumi, A., & Stapleton, C. (2009). Applying pedagogy

during game development to enhance game-based

learning. In Games: Purpose and potential in education

(pp. 127-162). Springer, Boston, MA.

Hrastinski, S. (2008). Asynchronous and synchronous e-

learning. Educause quarterly, 31(4), 51-55.

Jaypuriya, P. (2016). How Game-Based Learning

Redefines Engagement In eLearning. Retrieved from

https://elearningindustry.com/game-based-learning-

engagement-elearning

Kalogiannakis, M., & Papadakis, S. (2019). Evaluating pre-

service kindergarten teachers' intention to adopt and use

tablets into teaching practice for natural sciences.

International Journal of Mobile Learning and

Organisation, 13(1), 113-127.

Kalogiannakis, M., Nirgianaki, G.-M., & Papadakis, St.

(2018). Teaching magnetism to preschool children: the

effectiveness of picture story reading. Early Childhood

Education Journal, 46(5), 535-546.

Mautone, T., Spiker, V., & Karp, D. (2008). Using serious

game technology to improve aircrew training. In

Proceedings of the Interservice/Industry Training,

Simulation & Education Conference (I/ITSEC).

Mouaheb, H., Fahli, A., Moussetad, M., & Eljamali, S.

(2012). The serious game: what educational benefits?.

Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 5502-

5508.

Papadakis S., & Kalogiannakis, M. (2018). Using

Gamification for Supporting an Introductory

Programming Course. The Case of ClassCraft in a

Secondary Education Classroom. In A. Brooks, E.

Brooks, N. Vidakis (Eds), Interactivity, Game Creation,

Design, Learning, and Innovation. ArtsIT 2017, DLI

2017. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer

Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications

Engineering, vol 229, (pp. 366-375), Switzerland,

Cham: Springer.

Papadakis, S. (2018). The use of computer games in

classroom environment. International Journal of

Teaching and Case Studies, 9(1), 1-25.

Papadakis, S. (2020). Evaluating a game-development

approach to teach introductory programming concepts

in secondary education. Int. J. Technology Enhanced

Learning, 12(2), 127–145.

Papadakis, S., & Kalogiannakis, M. (2019). Evaluating the

effectiveness of a game-based learning approach in

modifying students' behavioural outcomes and

competence, in an introductory programming course. A

case study in Greece. International Journal of Teaching

and Case Studies, 10(3), 235-250.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On

the horizon, 9(5), 1-6.

Prensky, M. (2001). The games generations: How learners

have changed. Digital game-based learning, 1(1), 1-26.

Rosli, M. S., Mangshor, N. N. A., Sabri, N., & Ibrahim, Z.

(2017, October). Educational game as interactive

learning for hurricane safety. In 2017 7th IEEE

International Conference on System Engineering and

Technology (ICSET) (pp. 206-210). IEEE.

Teed, R., & Manduca, C. (2004, December). Teaching with

Games: Online Resources and Examples for Entry

Level Courses. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts.

Vidakis, N., Barianos, A. K., Trampas, A. M., Papadakis,

S., Kalogiannakis, M., & Vassilakis, K. (2019).

Generating Education in-Game Data: The Case of an

Ancient Theatre Serious Game. In Proceedings of the

11th International Conference on Computer Supported

Education (CSEDU 2019) (Vol. 1, pp. 36-43).

Vidakis, N., Barianos, K. A., Xanthopoulos, G., &

Stamatakis, A. (2018). Cultural Inheritance Educational

Environment: The Ancient Theatre Game ThimelEdu.

In European Conference on Games Based Learning

(pp. 730-XIII). Academic Conferences International

Limited.

Vidakis, N., Syntychakis, E., Kalafatis, K., Christinaki, E.,

& Triantafyllidis, G. (2015, August). Ludic educational

game creation tool: Teaching schoolers road safety. In

International Conference on Universal Access in

Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 565-576). Springer,

Cham.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

298