Deus versus Machina: How Much Health-supporting Technology Do

People Allow Depending on the Severity of the Disease?

Wiktoria Wilkowska

a

, Julia Offermann-van Heek

b

and Martina Ziefle

c

Human-Computer Interaction Center, RWTH Aachen University, Campus-Boulevard 57, 52074 Aachen, Germany

Keywords:

Technology Acceptance, Health-supporting Technology, Nursing Care, Disease.

Abstract:

Changes in demographic structures resulting in more and more overburdened healthcare systems require novel

solutions for modern societies. Members of aging populations are confronted with an ever increasing presence

of diseases and seniors frequently suffer from morbidity, which leads to a higher demand of nursing care on

the long run. Bottlenecks in this area can to some extent be relieved by the use of an assistive health-related

technology, but its acceptance and use is entirely dependent on the targeted users. This study considers the

perspective of severely ill persons regarding their nursing care and application of health-related technology

support. Using scenario-based empirical research, participants of an online-study (N = 585) were confronted

with three differently severe diseases and assessed aspects considered relevant for their nursing care and adop-

tion of assistive health-related technologies. Results show significantly differing opinions in dependency on

the severity of a disease. This study highlights several aspects that represent the perspective of diseased per-

sons and provides valuable insights into accepted use of health-enabling technologies and preferred models of

nursing care.

1 INTRODUCTION

While the growth of the world population on earth

continues to rise sharply, in many societies people

live now longer than some decades ago. The aver-

age age has been growing for many years, especially

in the industrialized countries, and the trend remains

unchanged for the time being. The declining number

of younger people and the simultaneously increasing

number of older people, however, continuously shift

the demographic structures. Also in Germany, the de-

mographic change has long since arrived (Statistische

¨

Amter des Bundes und der L

¨

ander, 2011).

The increasing proportion of aged individuals in

a population represents considerable challenges not

only to the economic sector, but it poses especially

challenging requirements to the feasibility and sus-

tainability of healthcare (Fleiszer et al., 2015). As the

probability of needing care increases with age, more

and more people are in need of care as society ages.

The result of this is that fewer and fewer young people

are forced to care for growing numbers of older indi-

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7163-3492

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1870-2775

c

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6105-4729

viduals, in many ways (Nowossadeck, 2013). Such

a situation causes a rising burden of healthcare ex-

penditures and leads in its consequence to a shortage

of professionals trained to work with the aging part

of the population. The more the population ages, the

more it becomes an important issue of how we are

going to pay for, and deliver, a quality care for the

seniors (Rashidi and Mihailidis, 2012).

At the same time, rapid advances in the informa-

tion technology enable new solutions that can, at least

to some extent, alleviate the challenging situation of

aging societies. In recent years, several integrative ap-

proaches have been developed, focusing on assistance

of individuals – especially seniors, diseased, and im-

paired persons – in their natural home environments.

Paradigms like pervasive computing, ambient intelli-

gence, and ambient assisted living aim at empowering

capabilities of humans by the means of digital envi-

ronments that are unobtrusive, interconnected, sensi-

tive, adaptive, and responsive to their needs (Sadri,

2011). Therein, a multitude of sensors and activators,

applications, functions, single devices to whole sys-

tems are included. Smart homes which are equipped

with such complex technology have a great potential

to support their inhabitants and improve the quality of

the time spent at home. Such technology-enhanced

26

Wilkowska, W., Heek, J. and Ziefle, M.

Deus versus Machina: How Much Health-supporting Technology Do People Allow Depending on the Severity of the Disease?.

DOI: 10.5220/0009370900260037

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2020), pages 26-37

ISBN: 978-989-758-420-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

environments are intended to provide greater levels

of independence for their inhabitants, and thus reduce

the need for institutionalized nursing facilities by ex-

tending the time that people can live in their familiar

surroundings.

In addition, information and communication tech-

nology (ICT) is increasingly being used in manage-

ment of (chronic) illnesses. Some common ICT-

applications, including home monitoring of vital pa-

rameters for chronically ill persons or communi-

cation via videophone consultations with medical

staff, facilitate the professional services (e.g., elec-

tronic health records) as well as knowledge man-

agement, such as care rules, protocols, or schedul-

ing (Celler et al., 2003). Jenssen et al. (2016) ar-

gue that there is a growing body of evidence that pa-

tient use of new technologies, enabling to communi-

cate with healthcare providers, can lead to a behavior

change and improved health outcomes. In this con-

text, telemedicine, eHealth, and telecare are key ap-

plications for ICT in healthcare delivery which aim at

specialist consultations and examinations of patients

health state through the use of telecommunication.

With all the available technical solutions, how-

ever, cooperative behavior and a largely accepted in-

teraction with the technology on the part of the per-

sons concerned is indispensable. There is a great

body of literature providing knowledge about applica-

tions for certain groups of diseases and, on the other

side, about the success or failure in their deployment.

In contrast, just a little is known about the willing-

ness to use technology depending on the varying de-

grees of severity of diseases. Therefore, the present

study focuses on the question how far persons suf-

fering from severe diseases allow the use of ambient

technologies which are meant to monitor their health

and support them in managing their day-to-day ne-

cessities associated with their illness. In a scenario-

based survey, we examined how the intention to use

such assistive health-related technology is connected

with emotional states of the persons concerned, who

is allowed to have a say in respect of their therapy and

rehabilitation, and what is the proportion of allowed

care support on the part of human and on the part of

technology.

2 RELATED WORK

In this section, the current research state on the accep-

tance of health-supporting technology innovations is

presented, taking a broad variety of technologies into

account. Also, the perspective of (chronically) ill per-

sons and the relevance of nursing care is stressed and

put in the context of the possibility to be supported by

appropriate technical applications. Finally, the under-

lying research questions are introduced.

2.1 (Health-supporting) Technology and

Its Acceptance

In view of the rapid development of technologies in

various fields, acceptance and use of innovations in

the area of information technology (IT) has been a

major concern for research and practice. Over the last

several decades, many theoretical models have been

proposed and validated in different contexts to exam-

ine the acceptance and to predict the use and long-

term adoption of particular innovations as reliable as

possible. The most prominent models were the Diffu-

sion of Innovation Theory (Rogers, 1983), Theory of

Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), Technology Accep-

tance Model (TAM; Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1989),

and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Tech-

nology (UTAUT; Venkatesh et al., 2003, 2012), which

have been proposed, examined, and extended, provid-

ing factors which are able to explain to a great ex-

tent the acceptance and use of different technologies.

However, even though the most dominant theoretical

frameworks in the recent years – TAM and UTAUT

– are very robust technology acceptance models, they

have also received criticism for disregarding the pos-

sible fluctuation over time (Peek et al., 2014).

For the present study, especially the context of

health-related technologies, and therein mainly (am-

bient) assistive technologies and systems, are gaining

particular interest as their primary objectives are to

monitor the health of the residents – mostly elderly

and impaired persons – and ensure an appropriate data

exchange as well as communication with physicians,

caring staff, and families. To provide a smoothly op-

erating health-related technology that is able to detect

critical situations, such as falls, relevant changes in

the individuals’ behaviors, and/or sleeping patterns,

a high degree of technology acceptance as well as

consideration of the users’ privacy concerns and ex-

pectations is required (e.g., Kirchbuchner et al., 2015;

Schomakers and Ziefle, 2019).

As research in this area has shown, acceptance

of medical assistance devices or systems, which pre-

dominantly address the senior part of the population,

is associated with a multitude of factors that play

a significant role. However, little is known about

whether or not older adults are ready to adopt and

use them (Jaschinski, 2014). In their review, Peek and

colleagues identified 27 factors influencing the accep-

tance of electronic technology for people who are ag-

ing in place and divided them into six clusters: i. con-

Deus versus Machina: How Much Health-supporting Technology Do People Allow Depending on the Severity of the Disease?

27

cerns regarding technology, ii. benefits of technology,

iii. need for technology, iv. alternatives to technol-

ogy, v. social influence, and vi. characteristics of

older adults (Peek et al., 2014). Nevertheless, a bulk

of these factors have not yet been tested in a quanti-

tative way. What has been substantiated by research,

however, is that acceptance of medical technologies

depends on perceptions of technology-related benefits

and barriers. Many studies in this context provided

evidence that assistive technologies were mostly as-

sessed favorably, whereas for elderly people and those

in need of care such benefits, like independent living,

feeling of safety, monitoring of health, and possibility

of staying at the own home, are especially appreciated

(Wilkowska, 2015; G

¨

overcin et al., 2016). Yet, per-

ceived obstacles can also cast a shadow over the moti-

vation for the use of assistive technologies. One of the

most decisive barriers are concerns referring to pri-

vacy (e.g., Yusif et al., 2016; Wilkowska et al., 2015),

which is a highly complex concept that involves dif-

ferent perspectives and dimensions (Little et al., 2007;

Schomakers and Ziefle, 2019). The desire for privacy

largely depends on the context and the individual at-

titudes (Bergstr

¨

om, 2015), but regarding the assistive

technology it has also been showed to vary between

different groups of individuals, like gender groups

or groups referring to the users’ health conditions

(Wilkowska and Ziefle, 2012), culture (Alag

¨

oz et al.,

2011), as well as social and physical environmental

factors (Himmel and Ziefle, 2016; Schomakers and

Ziefle, 2019). Other frequent barriers referring to the

acceptance of ambient technologies include, among

others, fears of surveillance and isolation from so-

cial contacts (van Heek et al., 2018), use of specific

types and placements of the technology (Himmel and

Ziefle, 2016; Kirchbuchner et al., 2015), perceived

control over the technology (van Heek et al., 2017),

trust, and the context of use (Montague et al., 2009;

van Heek et al., 2016; Wilkowska and Ziefle, 2018).

Given all the factors known to impact the health-

related technology acceptance and considering the

fact that in the given context the technology adop-

tion addresses especially the seniors, as they fre-

quently suffer from multi- and comorbidity, the ques-

tion arises if technology acceptance is significantly in-

fluenced by the severity of diseases.

2.2 Use of Health Information

Technologies for Diseases

Almost everyone wants to live as long as possible in-

dependently at home. However, age-related increase

of the probability for diseases and loss of functions in

persons aged 65 years and older frequently leads to an

ever greater loss of this autonomy (B

¨

ohm et al., 2009;

Barrett, 2011).

Older adults in this stage of life are likely to

suffer from one or more (chronic) diseases (Maren-

goni et al., 2011), experience changes of the im-

mune system and the endocrine system, which are

associated with disability, poorer health outcomes,

and lower quality of life (Fuchs et al., 2012). This

highly prevalent co-occurrence of chronic health con-

ditions among older individuals leads not only to the

need for preventive efforts, but a the same time to a

higher need for healthcare support, which can be, at

least partly, undertaken by the health-enabling tech-

nology equipment. Haux (2006) argued that with the

availability of health-enabling information technolo-

gies and the perspective of having adequate transin-

stitutional health information systems architectures,

a substantial improvement can be made to a better

patient-centered care, with possibilities ranging from

regional, national, to even global care. Applying ap-

proaches like AAL and ambient intelligence solutions

can even transfer such specific and to the individual

needs tailored care to private environments.

Such a development has the potential to contribute

to an efficient and affordable healthcare and would

support older and impaired persons to persevere an

independent life. However, in view of all the cur-

rent technological innovation little is known about the

willingness to use such assistive technology in the re-

lation to varying degrees of severity of disease by the

parties concerned. In this context, many ethical and

practical questions arise which refer not only to the

degree to which diseased persons wish to use such

technologies, but also to their emotional feelings con-

nected with their health condition and the associated

consequences. Also important are aspects, like how

should the patient’s care be structured and who may

decide on therapy and rehabilitation measures. In the

following, research questions of the present study are

described in more detail, attempting to empirically

elucidate these aspects, using a representative sample

of the German population.

2.3 Research Questions

Given the current demographic situation and the ex-

pected bottlenecks for the healthcare sector, on the

one side, and taking advantage of the sophisticated

health-supporting technologies, on the other, this

study focuses on questions referring to the individu-

als’ perceptions and acceptance of such innovations in

their lives and closer environments through the prism

of a serious illness.

In concrete terms, it is unclear how persons emo-

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

28

tionally sense when they are ill, which is probably sig-

nificantly associated with the given situations, states

of the disease, and not least people’s personalities. It

is worthwhile to examine whether certain profiles can

be assigned to certain disease-related situations, and

thus permit to develop meaningful strategies. More-

over, it is highly interesting to what extent such sen-

sations affect the decisions about the use of health-

supporting technologies. In this study, we therefore

ask (RQ1): Do emotional and ethical sensations ac-

companying ill persons differ in dependency of the

severity of the disease?

In this context, it is furthermore of interest how the

emotional state correlates with, or even significantly

affects, the motivation to be supported in case of ill-

ness. In terms of this study, we ask (RQ2): Does the

intention to use medical technology significantly vary

depending on the severity of the disease?

Moreover, in case of (severe) illnesses, people fre-

quently get in situations, which require decisions re-

garding their further/future treatment. In this context,

this study examines also (RQ3): To what extent other

important stakeholders (doctors, family members) are

allowed to make decisions about therapeutic and re-

habilitation measures associated with the disease?

Not least decisions about the use of health-

supporting technologies or applications are important

and in this context it is of interest, to what extent do

people affected by (severe) diseases allow technology

to support them in their convalescence? More specif-

ically, the question arises as to the extent to which

the use of health-supporting technologies may com-

pliment, (partially) take over the job, or even replace

caregivers. We therefore also examine in this study

(RQ4): To what extent do ill people allow the use of

medical technology next to the support of the human

caregiver(s)?

3 METHOD

In this section, the methodological approach, the op-

erationalization of the questions described are pre-

sented, and the study’s sample is introduced.

3.1 Quantitative Data Collection

This study used an online-survey as method for the

data collection and was structured as follows: At the

beginning, participants were asked for their socio-

demographic information regarding age, gender, pro-

fessional background, self-confidence in dealing with

technology (Beier, 1999) as well as general state of

health, subjective vitality (Ryan and Frederick, 1997),

and the general health condition coupled with the

presence or absence of chronic disease(s). In this part

of the survey, respondents also indicated their expe-

rience with health-supporting devices in their daily

lives.

Further, the survey focused on perceptions of cri-

teria related to aging, like a high quality of life in old

age (e.g., self-supply in daily life, competent medical

care, consistent social network, etc.) as well as as-

pects referring to positive and negative effects of ag-

ing [for details see Wilkowska et al. (2019)]. Another

part of the survey evaluated general attitudes towards

the use of medical technology (e.g., ”I can imagine

the use of medical technology.”) as well as the par-

ticipants’ (intended) use and assessments of health-

supporting technologies in the form of benefits and

barriers. Participants expressed their (dis-)agreement

to the respective items on a 6-point Likert-scale rang-

ing from 1 (”I do not agree at all”) to 6 (”I fully

agree”).

The last part of the questionnaire represents the

central content of this paper. Here, three different

scenarios were introduced, varying the severity of a

disease. The intention was to make the participants to

envision and, as far as possible, empathize with the ill

persons in the situations presented in the scenarios (S

I-III). In the following, the scenarios are presented in

their respective wordings:

Scenario I: ”After a serious car accident, you are

hospitalized. You have suffered various bone frac-

tures and your stay at the hospital will probably last

about 2 weeks. Afterwards, you have to expect many

weeks of healing (including a splint on your leg).

This situation implies also other consequences which

means that you are professionally absent for a few

months and need some nursing support at home (at

least for the time when you are bedridden and wear

plaster splints). However, according to doctors, a

complete recovery can be expected in the long term.”

Scenario II: ”After two heart attacks, you now suf-

fer from chronic heart failure in stage three. This

means that even slight physical exertion can cause

you to become exhausted, suffer from arrhythmias or

breathlessness. According to this, you need an inten-

sive (nursing) care and a lot of support in your every-

day life. In addition, you need to visit a doctor and

undergo rehabilitation measures on a regular basis.

The insurance experts classify you as no longer fit for

work due to your state of health and they force you

to take early retirement. The therapy of the disease is

possible to a certain extent, but it is also very com-

plex (i.e., drug therapy, rhythmological therapy with

pacemaker devices, targeted body training, appropri-

ate diet, etc.). By treating the causes and thanks to

Deus versus Machina: How Much Health-supporting Technology Do People Allow Depending on the Severity of the Disease?

29

the complex treatment measures, the prognosis is im-

proved, but unfortunately a high mortality rate is a

sad reality.”

Scenario III:”Please put yourself in the difficult sit-

uation in which you suffer from colorectal carcinoma

and your body is very severely impaired and weak-

ened as a result of a chemotherapy and the following

radiation therapy. You can manage your everyday life

only with the intensive support of a trained nursing

staff. You need support in terms of personal hygiene

and daily meals as well as regarding your mobility

needs. In this respect, you will be supported by both

professional carers and your family members. The

chances of recovery through surgery and chemother-

apy depend decisively on the stage and course of the

disease (on average the five-year survival rate is 40-

60%). Unfortunately, the near future is uncertain.”

The order of the scenarios was randomized. After

each scenario, participants worked through four ques-

tion blocks, referring to topics that are relevant for a

disease and the associated consequences. The first re-

ferred to the question who, and to what extent, may

have a say in decisions regarding a further medical

treatment. The possible stakeholders were ’myself’,

’the doctor’ and the ’nuclear family’, and the possible

answer alternatives were ’not at all’ (0%), ’a little’

(25%), ’partly’ (50%), ’for the most part’ (75%), ’en-

tirely’ (100%). The second block of questions used

the psychological method of the semantic differential

(Osgood et al., 1957), in which respondents’ judg-

ments had to be placed on a 10-step scale between two

poles of a dimension described by a pair of two ad-

jectives (e.g., threatening—conforming, hopeless—

hopeful, vulnerable—protected). With these, the state

of people’s emotional sensations and ethical percep-

tions was examined after each scenario. The third

group of questions referred to the intention to use

health-supporting medical equipment. We used the

three following items: ”In the context of the scenario,

...

• ...I can imagine the use of medical supportive

technology.”

• ...I consider the use of medical technology use-

ful.”

• ...I do not want to use medical technology at all.”

The respondents could express their (dis-)agreement

regarding these statements on a 6-point Likert-scale.

After re-coding of the negatively poled item, scales

for the intention to use the medical assistive technol-

ogy were built and reached sufficient internal validi-

ties (S I: α=.78, S II: α=.80, S III: α=.81); the par-

ticipants could reach in this regard 3 (=low intention)

to 18 points (=high intention). In the fourth block of

questions, the survey collected the participants’ opin-

ions about which caring/nursing model they would

ideally prefer with regard to the particular scenario.

Four alternatives were presented, and the respondents

had to choose the most preferred one: i. only nurs-

ing persons/caring staff (100% human), ii. for the

most part nursing staff and partly intelligent technol-

ogy (70% human and 30% medical technology), iii.

half intelligent technology and half nursing staff (50%

medical technology and 50% human), and iv. entirely

intelligent technology (100% medical technology).

Eventually, two last questions were asked to the

survey participant: “If you had the choice to decide:

may technology prolong life?” and “. . . may technol-

ogy delay dying?” In this case, only yes/no-answers

were possible.

3.2 Research Approach

The empirical study aimed at an investigation of opin-

ions regarding the support of individuals with frail

health conditions by medical technology (e.g., mon-

itoring technologies). For this purpose, respondents

assessed aspects related to decisions about handling

of situations of (severe) diseases and the associated

consequences in an online-survey.

Using a scenario-based method, participants were

introduced to three different situations referring to

varying severity of a medical condition. After each

scenario, which is treated in this study as an inde-

pendent variable, data on the following aspects, i.e.,

dependent variables, were collected:

• Ethical, emotional, and social sensations,

• Intention to use health-supporting technologies,

• Permission for others to participate in the deci-

sions on the future medical treatment,

• Desired proportion of the support from humans

(i.e., caregivers) vs. health-supporting technol-

ogy.

This study intended to provide an overview of the

above aspects depending on the severity of a disease

and the associated consequences (three scenarios as

described in Section 3.1), taking the German popu-

lation as an example. Figure 1 shows the schematic

outline of the examined variables.

3.3 Description of the Sample

A total of N=585 respondents completed the online

survey and were taken into consideration for statisti-

cal analyses in this study. A possibly broadest spec-

trum of the German population was addressed, in-

cluding differently aged male and female individuals,

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

30

Figure 1: Research Design of the Study.

with different professional backgrounds, life experi-

ences, and socio-economic statuses. The sample cov-

ered different professions, including individuals from

engineering and IT-sectors, education and economy

as well as health professionals and employers from

the social sector.

The participants were German adults, ranging in

age between 16 and 84 years (M=47.2; SD=16.6) and

the sample was quite balanced with 48% female and

52% male respondents. As the highest educational

levels, 21.5% of the participants reported to hold an

academic degree and 35.7% completed an apprentice-

ship. A further 19.1% of the sample stated to hold

a university entrance diploma, and 23.6% reported a

secondary school certificate as an educational gradu-

ation. The resulting know-how connected to the tech-

nology use and the general level of self-confidence in

this regard was for this sample quite high (M=18.2;

SD=4.4, from a maximum of 25 points).

Since health played a central role in the study, ad-

ditional information regarding health status and ex-

perience with the use of health-supporting technical

equipment was also asked for in the questionnaire.

More than one third of the sample (35.7%) reported

to be in very good health and further 18.8% stated to

suffer from a chronic condition, but to manage it very

well in the everyday life. Another considerable part

of the participants (41.9%) indicated to be somewhat

limited due to a chronic illness and 3.6% reported to

be dependent on the support of others (relatives / nurs-

ing care professionals). Moreover, less than half of

the sample (44.3%) reported experience with health-

supporting devices, like heart rate monitors, blood

pressure meters, activity monitors, or blood sugar me-

ters.

Participants were recruited for this study through

a professional survey panel platform, which enabled

to gather a representative sample of the German soci-

ety. They were paid for the participation by the survey

panel’s institute. The composition and the character-

istics of the sample are described further below.

4 RESULTS

For the statistical analyses of perceptions referring

to an accepted use of health-supporting technologies

in case of (severe) illness, repeated measures analy-

ses of variance (rmANOVA) were applied in order to

compare three different scenarios. As non-parametric

alternative the Friedman Test was used. For effect

size measures, the parameter partial eta squared (η

2

)

is reported according to (Cohen, 1988) and the sig-

nificance value in the multivariate tests was taken

from Wilks’ Lambda. If the assumption of sphericity

was violated (Mauchly’s Test < 0.05), Greenhouse-

Geisser correction was used. In the following, means

(M) and standard deviations (SD) are reported for de-

scriptive analyses and the level of statistical signifi-

cance (p) is set at the conventional level of 5%.

4.1 Emotional State of the Persons

Concerned

After each scenario, participants were asked to pos-

sibly realistically envision the outlined situation and

to rank their emotional states on scales, lying be-

tween two adjectives that refer to particular dimen-

sions. Figure 2 depicts the resulting means for the

three scenarios.

Figure 2: Ethical and Emotional Sensations for the Three

Illness-Scenarios (S I-III).

Evidently, the sensations significantly differed de-

pending on the scenario and this result is also reflected

in the statistical calculations. Only the polarity pro-

file of scenario I showed in part positive judgements:

Those affected felt in such a situation worthy, opti-

mistic, and hopeful, they were able to accept the dis-

ease to some extent, and regarded it as temporary. As

opposed to this, in the situation of scenario III, partic-

ipants felt threatened and vulnerable, and felt a certain

finality of their state. Repeated measures analyses of

Deus versus Machina: How Much Health-supporting Technology Do People Allow Depending on the Severity of the Disease?

31

variance with a Greenhouse-Geisser correction deter-

mined statistically significant differences between all

adjective pairs between the three degrees of severity

of a disease. The relevant statistical parameters de-

picting this effect are summarized in Table 1, provid-

ing evidence that the emotional and ethical sensations

sharply worsen the more severe the disease.

4.2 Intention to Use Medical

Technology

Given the different emotional states, it can be as-

sumed that these are associated with the willingness

to use medical supportive technologies. In this sec-

tion, it is therefore interesting (1) whether this will-

ingness changes significantly depending on the sever-

ity of the disease, and (2) to what extent this willing-

ness significantly correlates with the frames of mind

in each scenario.

A rmANOVA comparing the intention to use

health-supporting technology in dependency of the

severity of the disease revealed statistically significant

differences (F(1.9,1005.8)=7.3, p6.001, η

2

=.01).

Even though, according to the effect size the differ-

ences were small, the intention to use assistive tech-

nologies diminished the more severe was the illness.

Figure 3 depicts these differences.

Figure 3: Intention to Use Health-Supporting Technology

Depending on the Severity of an Illness.

In the next step, correlative relationships to the

previously collected emotional and ethical concerns

were analysed, relating these to the respective scales

for intention to use assistive technology in each sce-

nario. The resulting coefficients are summarized in

Table 2. For statistical purposes, the adjective pairs

were coded in such a way that the ”negative” expres-

sions show low numbers (adjectives on the left side,

e.g., lonely = 1) and the ”positive” expressions show

high values of the scale (adjectives on the right side,

e.g., social = 10).

The resulting coefficients generally display rather

weak correlations. It is striking that the associa-

tions are almost consistently significant in the sce-

nario with the most optimistic healing prospects (S

I). The mostly positive directions of the values sug-

gest that an affirmative attitude to the current state

of health goes along with a higher acceptance of the

use of health-supporting technology. Especially, the

confidence about the temporary and not stigmatizing

character of the health status as well as the hopeful ex-

pectation of healing indicate stronger correlative rela-

tions with the intention to use technological support.

Moreover, the clarity of correlative relationships

decreases in disease scenarios with more severe states

of health and less positive prospects for the future (S

II, S III). There, statistically significant associations

are less pronounced, but the alignment of the result-

ing coefficients is the same in both scenarios. The

results indicate that there is less willingness to use

the assistive technology equipment, the more threat-

ening and depending people perceive their health sta-

tus. In contrast, the more they accept their situation

and have a hopeful and socially oriented attitude, the

more the tendency for an open-minded use of techno-

logical support for their health.

Summing up, the results show that the emotional

state of the persons concerned is significantly corre-

lated to the intention to use health-supporting tech-

nology.

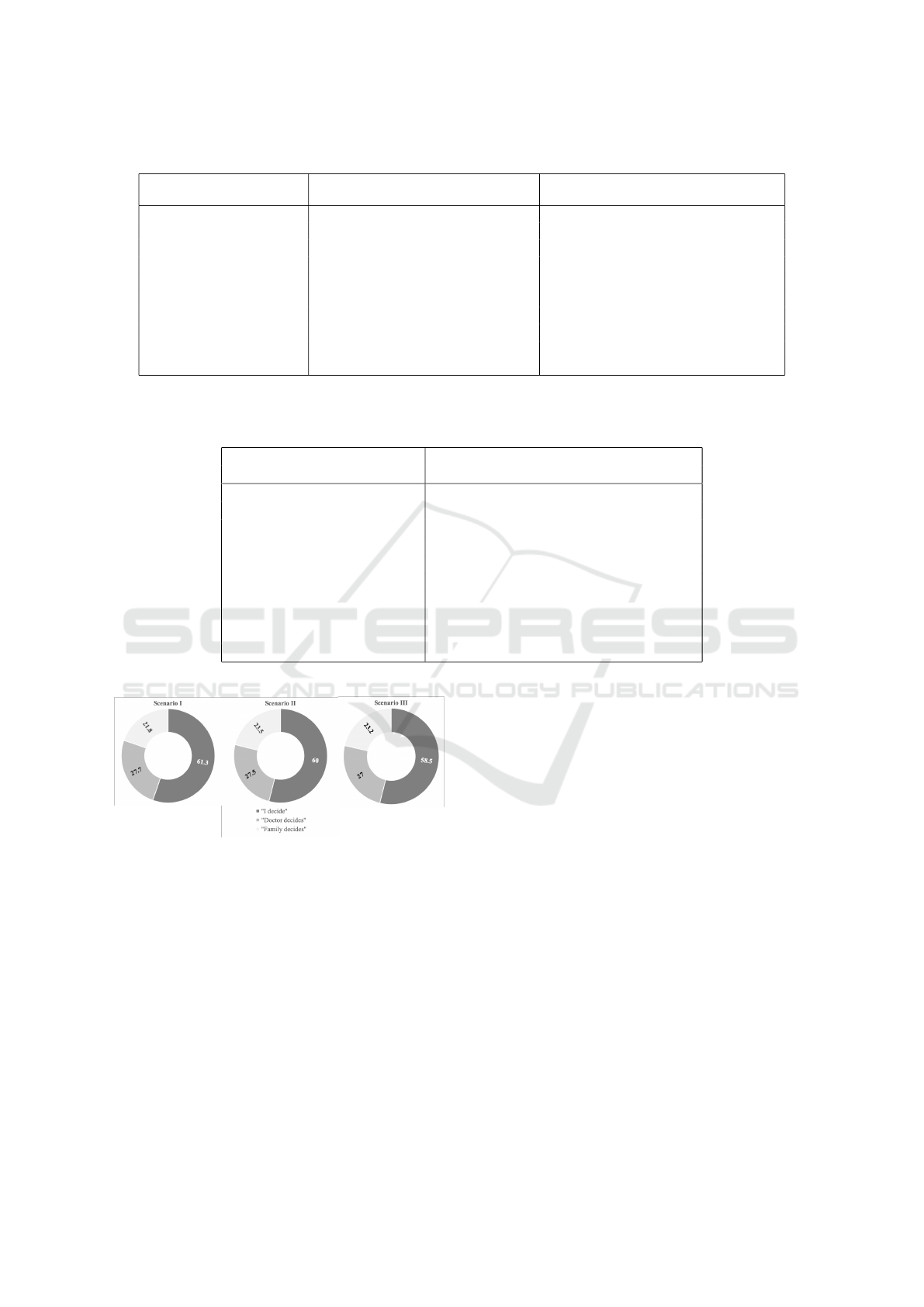

4.3 Who Is Allowed to Decide?

Closely linked to these considerations is also the

question of who can have a say in the various ther-

apeutic measures and thus in the shared use of infor-

mation technology for health purposes in the event of

a more or less serious illness. In the questionnaire, we

therefore asked the participants to quote the extent to

which they would allow – besides themselves – peo-

ple, like the doctor in charge and family members, to

have a say in decisions regarding their further treat-

ment (again depending on the severity of the disease

in the three scenarios). In order to ease the visibility

and comprehensibility of the results, only the results

of the answers relating to 100% decisions (”may fully

decide”) are presented below (Figure 4).

Interestingly, the resulting percentages did not dif-

fer considerably in the scenarios. This finding leads

to the conclusion that independently from the severity

of the disease individuals mostly wish to decide about

their medical treatment by themselves. With regard to

the ’other people’ who might have a say in the mat-

ter of the therapeutic treatment in case of illness, the

preferences are distributed between the treating physi-

cians and family members, although the proportion is

slightly higher for the physicians.

Thus, according to the results, in case of ill-

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

32

Table 1: Effect of the Severity of a Disease on Emotional and Ethical Sensations in Persons Concerned.

Pairs of adjectives Within-Subjects Effects Means (SD)

Scenario I Scenario II Scenario III

threatening vs. comforting F(1.8,969.3)=275.7, p6.001, η

2

=.34 5.3 (2.4) 3.2 (2.4) 2.9 (2.6)

unworthy vs. worthy F(1.9,982.8)=156.5, p6.001, η

2

=.14 5.0 (2.3) 4.3 (2.2) 3.6 (2.2)

uncontrol. vs. controllable F(1.9,1032.8)=223.3, p6.001, η

2

=.29 6.2 (2.4) 4.4 (2.5) 3.7 (2.7)

depending vs. autonomous F(1.9,999.8)=84.1, p6.001, η

2

=.14 5.0 (2.2) 4.3 (2.2) 3.6 (2.2)

lonely vs. social F(1.9,1054.7)=105.8, p6.001, η

2

=.16 5.4 (2.3) 4.3 (2.3) 4.0 (2.4)

pessimistic vs. optimistic F(1.9,882.7)=215.9, p6.001, η

2

=.31 6.8 (2.3) 5.0 (2.3) 4.4 (2.3)

vulnerable vs. protected F(1.8,983.6)=197, p6.001, η

2

=.27 5.2 (2.3) 3.6 (2.4) 3.2 (2.5)

stigmatizing vs. acceptable F(1.9,947.7)=123.2, p6.001, η

2

=.20 6.8 (2.0) 5.6 (2.1) 5.2 (2.2)

final vs. temporary F(1.7,927.3)=396.4, p6.001, η

2

=.42 6.9 (2.4) 3.7 (2.2) 3.6 (2.4)

hopeless vs. hopeful F(1.8,991.1)=339.5, p6.001, η

2

=.38 7.0 (2.3) 4.5 (2.5) 4.0 (2.5)

Table 2: Pearson’s Correlation Coefficients between the Intention to Use (ItU) Health-Supportive Technologies and the Emo-

tional States Based on Pairs of Adjectives in the Three Scenarios (Significant Values Are Bold; Level of Significance: *p6.05,

**p6.01).

Pairs of adjectives ItU

Scenario I Scenario II Scenario III

threatening vs. comforting r = .04 r = −.17** r = −.16**

unworthy vs. worthy r = .18** r = .09* r < .01

uncontrolable vs. controllable r = .18** r = .08 r = −.08

depending vs. autonomous r = − .11** r = −.10* r = −.17**

lonely vs. social r = .12** r = .13** r = .10*

pessimistic vs. optimistic r = .18** r = .04 r = .02

vulnerable vs. protected r = .09* r = −.02 r = −.08

stigmatizing vs. acceptable r = .21** r = .16** r = .12**

final vs. temporary r = .30** r = −.06 r = .01

hopeless vs. hopeful r = .38** r = .13** r = .11**

Figure 4: Percentage Rates Presenting Decisions about

Who May Fully Decide about the Further Therapeutic

Treatment Depending on the Severity of the Disease.

ness people predominantly wanted to decide by them-

selves, even when their state of illness was very se-

vere.

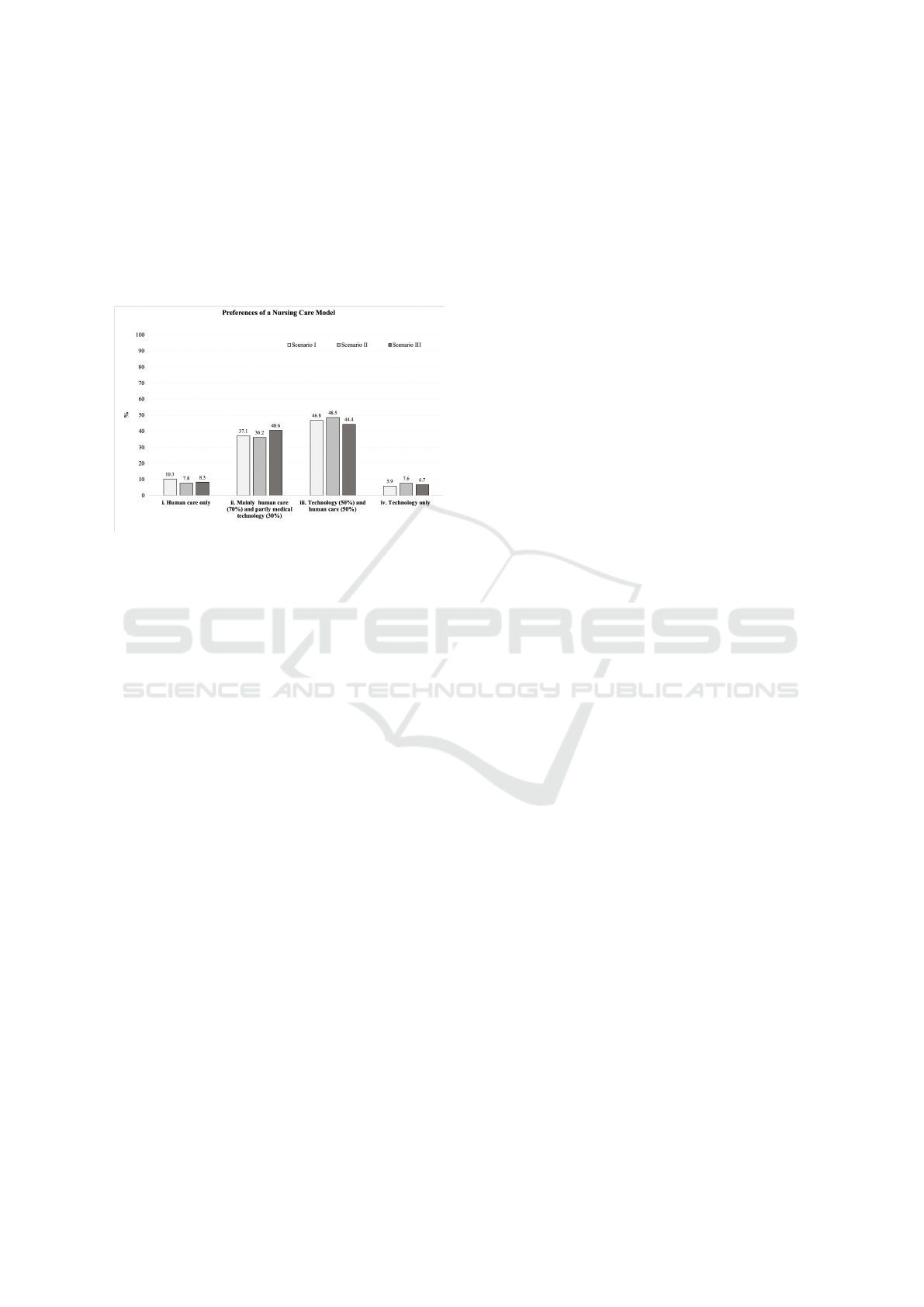

4.4 Human vs. Technology in the

Nursing Care?

Finally, one of the research questions referred to the

extent to which ill people would allow the use of med-

ical technology next to the support of human care-

giver(s).

To examine this question, after each scenario re-

spondents had to choose one preferred caring model

among the following four alternatives: i. 100% hu-

man care (coded as 1), ii. mainly professional hu-

man carers (70%) and partly medical assistive tech-

nology (30%; coded as 2), iii. partly assistive tech-

nology (50%) and partly human care (50%; coded as

3) and iv. 100% technology (coded as 4). In order

to determine statistically significant differences be-

tween the preference models, Friedman test was ap-

plied. Results of this non-parametric measure suggest

that there are significant differences in the preferences

of the nursing care models depending on the sever-

ity of the disease (χ

2

(2)=7.6, p=.022, n=543). Fig-

ure 5 summarizes the preferences for all caring mod-

els, depicting the three scenarios which refer to the

severity of the disease. It can be seen that the partici-

pants mostly preferred the mixed models (ii. and iii.),

where in case of illness a combined support of hu-

man and technology is offered. The percentage rates

resulting for the three scenarios do not vary signifi-

cantly within the different caring models. Overall, the

highest percentage rates resulted for the caring model,

where technology (50%) and human support (50%)

are balanced (iii.). It is noteworthy, however, that per-

Deus versus Machina: How Much Health-supporting Technology Do People Allow Depending on the Severity of the Disease?

33

sons suffering from a serious illness, like the colorec-

tal cancer in our example (S III), rather prefer the al-

ternative of ”mainly human (70%) and partly technol-

ogy care (30%)” (ii.), while this caring model in the

less fatal health conditions (S I, S II) was slightly less

preferred. On the contrary, the alternatives of ’100%

human care’ (i.) and ’100% technology’ (iv.) were

chosen only by small proportions of the sample.

Figure 5: Percentage Rates in Preferences of Nursing Care

Models Depending on the Severity of the Disease.

These outcomes let conclude that regardless of the

severity of the disease the preferred models of care

allow for both human carers and technology to take

care for, and support, their health.

5 DISCUSSION

Aging in place in a familiar environment and as close

as possible to the own family is one of the most as-

pired ways of life for seniors. However, with increas-

ing age people are often tormented by (multiple) ill-

nesses, which thwart these plans or make this wish

even impossible due to the needs of care and support

for their everyday lives. Today’s technology develop-

ment has great potential in the area of healthcare, to

support people who need clear therapy for the conva-

lescence process or rehabilitation measures, and also

for those who need just some support in mastering of

their everyday tasks. This can happen, at least partly,

in their own home environments, using the merits

of the ambient technologies or systems, sensor-based

networks for activity monitoring, fall detection, and

various other health-supporting applications.

But how do the elderly ”tick”? A lot of research

has been done to develop, evaluate, and optimize

current technical applications, but relatively little is

known about what the potential users – in this case

the elderly, impaired, and chronically ill ones – want,

how they feel about their particular state of health, and

what they are willing to allow regarding these techni-

cal solutions in their individual situations. There are

some facts which one must not lose sight of: First,

the today’s old people are mostly technologically so-

cialized in different matter (Sackmann and Winkler,

2013) than the so-called generation X or Y, and they

have completely different relations to the use of tech-

nologies. Second, in an acute state of illness, the pri-

orities lie in the recovery and may be completely dif-

ferent from those in a normal or stable state of health:

It is thus quite conceivable that in such a state one no

longer has the capacity to use, or learn to use, tech-

nologies even when these are very supportive. Third,

according to studies (e.g., Loft et al., 2019) and from

the psychological point of view, human contact is of

the utmost importance for recovery and mental stabil-

ity, especially for the elderly, who are often socially

isolated or neglected. It may therefore be the case

that diseased persons turn generally more to people

than to technology.

5.1 Perceptions of the Diseased Persons

The presented study examined such considerations

and can answer the research questions asked at the

beginning on the basis of empirical data. Findings

revealed that the emotional and ethical sensations

sharply worsen, the more severe is the disease. Even

if this result is not particularly surprising in itself, in

the context studied here this is an important insight.

As opposed to health conditions which have

prospects of a secure recovery, seriously ill people

feel threatened, vulnerable, and dependent. These in-

dividuals experience a certain sense of finality and un-

controlled state of their health, and they find it diffi-

cult to show a hopeful attitude. In addition, the emo-

tional states have been shown to be essentially related

to the willingness of using health-enabling technolo-

gies. Statistical calculations provided evidence that

the intention to use the health-assisting technology di-

minishes with the severity of the disease; even though

the here provided effect was not very strong. Corre-

lating the intention to use the health-enabling equip-

ment with the emotional states of persons suffering

from differently severe diseases suggests that an affir-

mative attitude due to an optimistic health prospects

goes along with a higher technology acceptance. On

the other side, there is also less willingness to use the

assistive technology, the more threatening and depen-

dent individuals perceive their health situation.

Therefore, in order to actually make use of the

support offered by medical technology at this point

in people’s lives, a special sure instinct is needed.

Because no one can expect that seriously ill people

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

34

leave the decision about the necessary treatment in the

hands of others (e.g., medical professionals). On the

contrary, the current study showed that regardless of

the severity of the disease people want to decide pri-

marily by themselves about measures regarding their

therapy and/or rehabilitation. Although they grant

doctors – in particular – but also family members a

say in decisions about their health, according to the

above findings they want to keep the final word, even

if they are terminally ill.

In addition, there were only few of those who pre-

fer a nursing care based only on the technology or

coming only from the human. The majority of respon-

dents preferred models combining the sensitivity of a

human carer and the efficiency of the smart assistive

technologies. In this regard, individuals with rather

positive chances for recovery tend to permit more sup-

port from the technology side (50%), whereas the se-

riously ill persons would rather choose the care alter-

native with a higher proportion of human care (70%)

and less proportion of technology care (30%). In any

case, it seems to be an unanimous opinion that the use

of health-related technology should always be a free

choice of the persons concerned. This result corrob-

orates previous findings (e.g., Hofstede et al., 2014)

and shows that there is a fine line in decisions between

human (’deus’) vs. machine in disease situations and

this quite complex process cannot be unambiguously

determined beforehand.

Returning to the research questions formulated at

the beginning, the following findings can be summa-

rized on the basis of the presented results:

• Emotional and ethical sensations accompanying

ill persons significantly differ depending on the

severity of a disease and are significantly re-

lated to the intention to use assistive technology

for health purposes. The intention itself differs

slightly between the scenarios, decreasing with

the increasing severity of an illness.

• Other persons, considered important in the course

of a disease (e.g., doctors, family members), are

allowed to support decisions about the associated

therapeutic and rehabilitation measures. Yet, a

majority of respondents wishes to make such de-

cisions by themselves, regardless of the severity

of their illness.

• Ill people allow the use of medical technology,

but they would rarely rely only on the technology

as caregiver/support in case of severe diseases.

Much more, the more severe is the health status of

the person concerned the more mixed caring mod-

els are desired with the tendency to prefer more

nursing care from professional staff (70%) than

from technology (30%).

On a final note, it is valuable to take a closer look

at one of the last questions of the survey, asking if

technology is allowed to prolong life. Almost 76%

of the participants responded with ”yes”, but still one

out of four persons (24%) does not allow technology

to extend his or her greatest good. At this point, it is

not clear – yet of great interest – who are the persons

which decide against the support brought by techni-

cal innovations, but the result itself represents an im-

portant ethical question, which cannot be disregarded

in the context of using assistive technology to deliver

healthcare.

5.2 Limitations and Directions for

Future Research

Especially the last described result makes the impor-

tance of further, deepening research in this area par-

ticularly plausible. In addition, there are still some

limitations of the present research to be addressed in

future studies.

In the first place, it should not be disregarded that

this study only depicts the perceptions and opinions

of people who have envisioned particular health states

on the basis of disease scenarios, and are not based

on real experiences of ill persons with acutely or in

the past experienced disease states. This can lead to

considerable distortions and should thus be validated

in the future to get even more informative results.

Another limitation applies to the fact that the pre-

sented results are very general. Yet, the interesting

questions are hidden in the particular participants’

characteristics, which are considered important for

the issues presented, like age groups, different lev-

els of technical confidence, and preparedness to use

technology solutions for health matters. Further stud-

ies should thus focus more on these aspects.

In addition, to enrich understanding of peo-

ple’s assessments and their intended use of health-

supporting equipment in case of illness, examinations

of their personality as well as compliance would pre-

sumably add value to the current research. Insights in

this regard could enable to evolve appropriate strate-

gies to the therapy and rehabilitation measurements

for people with different illness and personality pro-

files.

Overall, this study gives first insights into the rel-

evant topic of the perspective of ill persons for whom

the use of assistive health-related technologies repre-

sents an important alternative enabling to live an au-

tonomous life. Further studies are necessary from the

perspective of those affected to deepen this knowl-

edge and to apply it in the practice in an optimized

way.

Deus versus Machina: How Much Health-supporting Technology Do People Allow Depending on the Severity of the Disease?

35

6 CONCLUSIONS

User perceptions of, and their willingness to use, elec-

tronic health-related technology are important deter-

minants of its successful implementation. The knowl-

edge about how to provide an accepted technology-

enhanced assistance is, however, multifaceted and

requires especially the perspective of persons con-

cerned. This study highlights several aspects that rep-

resent the perspective of the diseased and provides

valuable hints on preferred models of nursing care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors thank all respondents for the participation

and sharing their opinions on aspects referring to the

acceptance of assisting technologies in health-related

context. This work resulted from the project PAAL

(Privacy Aware and Acceptable Lifelogging services

for older and frail people) and was funded by the

German Federal Ministry of Education and Research

(16SV7955).

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Or-

ganizational behavior and human decision processes,

50(2):179–211.

Alag

¨

oz, F., Ziefle, M., Wilkowska, W., and Valdez, A. C.

(2011). Openness to accept medical technology-a cul-

tural view. In Symposium of the Austrian HCI and Us-

ability Engineering Group, pages 151–170. Springer.

Barrett, L. L. (2011). Healthy@ home 2.0. AARP Research

& Strategic Analysis.

Beier, G. (1999). Kontroll

¨

uberzeugungen im Umgang mit

Technik [Locus of control when interacting with tech-

nology]. Report Psychologie, 24(9):684–693.

Bergstr

¨

om, A. (2015). Online privacy concerns: A broad

approach to understanding the concerns of different

groups for different uses. Computers in Human Be-

havior, 53:419–426.

B

¨

ohm, K., Mardorf, S., N

¨

othen, M., Schelhase, T., Hoff-

mann, E., Hokema, A., Menning, S., Sch

¨

uz, B., Sul-

mann, D., Tesch-R

¨

omer, C., et al. (2009). Gesundheit

und krankheit im alter [health and disease in old age].

Celler, B. G., Lovell, N. H., and Basilakis, J. (2003). Us-

ing information technology to improve the manage-

ment of chronic disease. Medical Journal of Australia,

179(5):242–246.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behav-

ioral sciences. 2nd.

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of

use, and user acceptance of information technology.

MIS quarterly, pages 319–340.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., and Warshaw, P. R. (1989).

User acceptance of computer technology: a compari-

son of two theoretical models. Management science,

35(8):982–1003.

Fleiszer, A. R., Semenic, S. E., Ritchie, J. A., Richer, M.-C.,

and Denis, J.-L. (2015). The sustainability of health-

care innovations: a concept analysis. Journal of ad-

vanced nursing, 71(7):1484–1498.

Fuchs, J., Busch, M., Lange, C., and Scheidt-Nave,

C. (2012). Prevalence and patterns of morbidity

among adults in germany. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-

Gesundheitsforschung-Gesundheitsschutz,

55(4):576–586.

G

¨

overcin, M., Meyer, S., Schellenbach, M., Steinhagen-

Thiessen, E., Weiss, B., and Haesner, M. (2016).

Smartsenior@ home: Acceptance of an integrated am-

bient assisted living system. results of a clinical field

trial in 35 households. Informatics for health and so-

cial care, 41(4):430–447.

Haux, R. (2006). Individualization, globalization and

health–about sustainable information technologies

and the aim of medical informatics. International

journal of medical informatics, 75(12):795–808.

Himmel, S. and Ziefle, M. (2016). Smart home medical

technologies: users’ requirements for conditional ac-

ceptance. i-com, 15(1):39–50.

Hofstede, J., de Bie, J., Van Wijngaarden, B., and Heij-

mans, M. (2014). Knowledge, use and attitude to-

ward ehealth among patients with chronic lung dis-

eases. International journal of medical informatics,

83(12):967–974.

Jaschinski, C. (2014). Ambient assisted living: towards a

model of technology adoption and use among elderly

users. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International

Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Com-

puting: Adjunct Publication, pages 319–324. ACM.

Jenssen, B. P., Mitra, N., Shah, A., Wan, F., and Grande, D.

(2016). Using digital technology to engage and com-

municate with patients: a survey of patient attitudes.

Journal of general internal medicine, 31(1):85–92.

Kirchbuchner, F., Grosse-Puppendahl, T., Hastall, M. R.,

Distler, M., and Kuijper, A. (2015). Ambient intelli-

gence from senior citizens’ perspectives: Understand-

ing privacy concerns, technology acceptance, and ex-

pectations. In European Conference on Ambient Intel-

ligence, pages 48–59. Springer.

Little, L., Marsh, S., and Briggs, P. (2007). Trust and pri-

vacy permissions for an ambient world. In Trust in

e-services: Technologies, Practices and Challenges,

pages 259–292. IGI Global.

Loft, M. I., Martinsen, B., Esbensen, B. A., Mathiesen,

L. L., Iversen, H. K., and Poulsen, I. (2019). Call

for human contact and support: an interview study ex-

ploring patients’ experiences with inpatient stroke re-

habilitation and their perception of nurses’ and nurse

assistants’ roles and functions. Disability and rehabil-

itation, 41(4):396–404.

Marengoni, A., Angleman, S., Melis, R., Mangialasche, F.,

Karp, A., Garmen, A., Meinow, B., and Fratiglioni,

L. (2011). Aging with multimorbidity: a system-

ICT4AWE 2020 - 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

36

atic review of the literature. Ageing research reviews,

10(4):430–439.

Montague, E. N., Kleiner, B. M., and Winchester III, W. W.

(2009). Empirically understanding trust in medical

technology. International Journal of Industrial Er-

gonomics, 39(4):628–634.

Nowossadeck, S. (2013). Demografischer wandel,

pflegebed

¨

urftige und der k

¨

unftige bedarf an

pflegekr

¨

aften. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheits-

forschung - Gesundheitsschutz, 56(8):1040–1047.

Osgood, C. E., Suci, G. J., and Tannenbaum, P. H. (1957).

The measurement of meaning. Number 47. Urbana:

University of Illinois Press.

Peek, S. T., Wouters, E. J., Van Hoof, J., Luijkx, K. G.,

Boeije, H. R., and Vrijhoef, H. J. (2014). Factors in-

fluencing acceptance of technology for aging in place:

a systematic review. International journal of medical

informatics, 83(4):235–248.

Rashidi, P. and Mihailidis, A. (2012). A survey on ambient-

assisted living tools for older adults. IEEE journal of

biomedical and health informatics, 17(3):579–590.

Rogers, E. M. (1983). Diffusion of innovations. New York,

The free press.

Ryan, R. M. and Frederick, C. (1997). On energy, personal-

ity, and health: Subjective vitality as a dynamic reflec-

tion of well-being. Journal of personality, 65(3):529–

565.

Sackmann, R. and Winkler, O. (2013). Technology gener-

ations revisited: The internet generation. Gerontech-

nology, 11(4):493–503.

Sadri, F. (2011). Ambient intelligence: A survey. ACM

Computing Surveys (CSUR), 43(4):36.

Schomakers, E.-M. and Ziefle, M. (2019). Privacy percep-

tions in ambient assisted living. In Proceedings of

the 5th International Conference on Information and

Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-

Health (ICT4AWE 2019), pages 205–215.

Statistische

¨

Amter des Bundes und der L

¨

ander, S. A. d. B. u.

d. L. (2011). Demografischer wandel in deutschland–

bev

¨

olkerungs- und haushaltsentwicklung im bund und

in den l

¨

andern (heft 1). Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bun-

desamt.

van Heek, J., Arning, K., and Ziefle, M. (2016). The

surveillance society: Which factors form public ac-

ceptance of surveillance technologies? In Smart

Cities, Green Technologies, and Intelligent Transport

Systems, pages 170–191. Springer.

van Heek, J., Himmel, S., and Ziefle, M. (2017). Helpful but

spooky? acceptance of aal-systems contrasting user

groups with focus on disabilities and care needs. In

ICT4AgeingWell, pages 78–90.

van Heek, J., Ziefle, M., and Himmel, S. (2018). Care-

givers’ perspectives on ambient assisted living tech-

nologies in professional care contexts. In ICT4AWE,

pages 37–48.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., and Davis, F. D.

(2003). User acceptance of information technology:

Toward a unified view. MIS quarterly, pages 425–478.

Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., and Xu, X. (2012). Consumer

acceptance and use of information technology: ex-

tending the unified theory of acceptance and use of

technology. MIS quarterly, 36(1):157–178.

Wilkowska, W. (2015). Acceptance of eHealth technology

in home environments: Advanced studies on user di-

versity in ambient assisted living. Apprimus Verlag.

Wilkowska, W., Offermann-van Heek, J., Brauner, P., and

Ziefle, M. (2019). Wind of change? attitudes towards

aging and use of medical technology.

Wilkowska, W. and Ziefle, M. (2012). Privacy and data se-

curity in e-health: Requirements from the user’s per-

spective. Health informatics journal, 18(3):191–201.

Wilkowska, W. and Ziefle, M. (2018). Determinants of trust

in acceptance of medical assistive technologies. In In-

ternational Conference on Information and Commu-

nication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health,

pages 45–65. Springer.

Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M., and Himmel, S. (2015). Percep-

tions of personal privacy in smart home technologies:

Do user assessments vary depending on the research

method? In International Conference on Human

Aspects of Information Security, Privacy, and Trust,

pages 592–603. Springer.

Yusif, S., Soar, J., and Hafeez-Baig, A. (2016). Older peo-

ple, assistive technologies, and the barriers to adop-

tion: A systematic review. International journal of

medical informatics, 94:112–116.

Deus versus Machina: How Much Health-supporting Technology Do People Allow Depending on the Severity of the Disease?

37