Measures of Monetary Policy in Latin America

Trung Thanh Bui

Falcuty of Economics and Business Administration,

University of Szeged, Szeged, Hungary

Keywords: Monetary Policy, Instruments, Interest Rate, Money Supply, Latin America.

Abstract: Although the instrumentation of monetary policy is still constantly debated in the existing literature, there is

a paucity of studies investigating this problem in emerging economies, especially after the recent global

financial crisis. The objective of the paper is to investigate the role of interest rate and money supply as an

overall measure of monetary policy in four major Latin America economies that follow the inflation targeting

framework. Evidence from causality test and the analysis of impulse response function shows that both

indicators have explanation for price movement. The price puzzle is clearly visible follows positive shocks to

interest rate. These findings suggest that a composite index can be a better measure of monetary policy and

other means should be conducted to improve the performance of the interest rate policy.

1 INTRODUCTION

The choice of an appropriate measure of monetary

policy is of importance in the analysis of monetary

policy (Bernanke–Mihov 1998). There are two main

reasons (Romer–Romer 2004). Firstly, it alleviates

the effect of the endogenous interaction between

changes in monetary policy and changes in the state

of the economy, thereby alleviating the problem of

underestimating the effect of monetary policy on

output and prices. Secondly, a representative

monetary policy indicator also helps to reveal the true

interaction between monetary policy and

macroeconomic outcomes.

Most of studies on monetary policy in emerging

economies have based on the prior that monetary

policy is properly measured by a single indicator such

as interest rate. See, for instance, Cermeño et al.

(2012) for Mexico; Furlani et al. (2010), Sánchez-

Fung (2011), Jawadi et al. (2014) for Brazil; or De

Mello–Moccero (2011) for 4 Latin America

countries. However, the practical conduct of

monetary policy in emerging economies raises doubts

on the effectiveness of interest rate as the sole

measure of monetary policy, especially during the

post-crisis period. Although Latin America countries

have decided on interest rates as an official

operational target since the adoption of inflation-

targeting framework in the 1990s, they also depend

on other instruments to affect reserve money such as

reserve requirements, discount windows, and

exchange rate interventions. Such a multiple

instrument framework can stem from the insufficient

knowledge about the structure of the economy or the

distortion effect of objectives other than price

stability. For instance, the Central Bank of Brazil

simultaneously pursued several targets after crisis,

including inflation-targeting, flexible exchange rate,

and macroprudential regulations (Jawadi et al. 2014).

Apart from price stability, Bank of Mexico also

implicitly aimed at objectives such as output stability

(Cermeño et al. 2012).

Furthermore, previous studies are limited to the

pre-crisis period and, to the best knowledge of the

author, there is no studies investigating the relative

performance of interest rate and monetary aggregate

as an overall measure of monetary policy in Latin

America. Therefore, the performance of the two

indicators remain ambiguous in the last decade. Since

the choice of an appropriate monetary policy

indicator is the first step to analyse further issues of

monetary policy such as effectiveness, monetary

policy rules, or transmission channels, it is of

importance to have a rigorous study on the

effectiveness of various instruments.

This paper sheds light on some crucial issues

related to indicator problem of the monetary policy

analysis in four emerging economies in Latin

America, including Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and

Mexico. What is the superior indicator in Latin

Bui, T.

Measures of Monetary Policy in Latin America.

DOI: 10.5220/0009343600270036

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2020), pages 27-36

ISBN: 978-989-758-422-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

27

America? Is the usefulness of monetary policy

indicators different after the global financial crisis?

What is the role of monetary aggregates in the

conduct of monetary policy? The investigation of

these questions provides evidence about the role of

various monetary policy indicators in emerging

economies that follow inflation targeting framework.

Furthermore, understanding the instrumentation over

different time horizons contributes to the effective

implementation of monetary policy.

To compares the significance of money supply

and interest rate as an overall measure of monetary

policy on two bases. First, the causality analysis is

conducted to investigate the predictive power of

changes in a monetary policy indicator on inflation.

Such an analysis is of importance to examine the

tightness between the indicator and inflation. Second,

the analysis of the impulse response of inflation to a

monetary policy indicator indicates the magnitude of

the effect of monetary policy on inflation. The

preferred indicator of monetary policy should show

the dominance in fulfilling the objective of price

stability.

Turning to the key findings, the paper found that

there is shifts in the causal effect of interest rate

instrument in Latin America after crisis. In addition,

evidence from impulse response function indicates

that price puzzle is clearly visible after positive

interest rate shocks. On the contrary, inflation

response to monetary aggregates is more consistent

with the prediction of monetary theories. The results

of causality and impulse response analysis suggest

that neither interest rates nor money supply

sufficiently measures the stance of monetary policy in

Latin America. Therefore, a composite measure can

be a better measure of monetary policy. Other

suggestions are related to the improvement of the

compliance of the basic principle of inflation

targeting such as increasing the independence of

central banks or the performance of inflation forecast.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides theoretical background for the

optimal choice of monetary policy indicators and

empirical studies of instrument problems in emerging

economies and Latin America in particular. Section 2

discusses how to investigate the relative significance

of interest rate and money supply instrument. Section

4 presents and discusses empirical results. Section 5

is conclusions and policy implications.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Monetary Policy Indicator

The indicator problem of monetary policy refers to

the controversy about the effectiveness of interest rate

and money supply in signalling the stance of

monetary policy. It arises because of incomplete

knowledge about the structure of the economy as well

as the existence of lagged effect of monetary policy

on economic targets.

Poole (1970) analysed the optimality of interest

rate and money supply based on a simple IS/LM

framework. Two primary assumptions of the analysis

are that monetary authorities have no errors in

controlling interest rate or money supply and they

must choose only one instrument to minimize the

volatility of output. The conclusion is that money

supply is preferred to deal with shocks from the real

sector while interest rate is superior in dealing with

shocks from monetary sector.

Following studies (Bhattacharya–Singh 2008,

Singh–Subramanian 2008) reached a similar

consensus. Likewise, Atkeson et al. (2007) argued

that monetary policy instruments can be ranked in

terms of tightness or transparency. They define

tightness as the strength of the linkage between

monetary policy instruments and target variables such

as inflation or output growth and define transparency

as the observability of instrument adjustments by the

public. Based on these criteria, they rank interest rates

as the best instrument because it has natural

advantages over exchange rate instrument and money

supply instrument in term of tightness and

transparency. Exchange rate is less preferred

instruments and money supply is at the bottom.

However, the consensus under Poole (1970)

framework may fall if real/ monetary shocks are

serially related or monetary authorities have

imperfect knowledge about the economy (Howells–

Bain 2003). The serial correlation is likely to happen

because monetary authorities concern about

smoothing the path of interest rate/money supply. The

violation also happens when there is lag in the system

or changes in the slope of IS and LM curve.

Moreover, Poole (1970) derives the consensus from

an ad hoc macroeconomic models, whereby the

derivation of aggregate demand and aggregate supply

does not base on consistent assumptions about the

behaviour of consumers and firms.

In the context of emerging economies, Poole

(1970) analysis has three primary limitations. First,

monetary authorities in emerging economies cannot

control monetary policy instruments as well as

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

28

counterparts in advanced economies. The low

performance is caused by the underdevelopment of

the financial system or the low expertise of

policymakers. Therefore, errors in controlling

instruments can be large and the conclusion about the

superiority of interest rate and money supply is not

clear-cut as the simple analysis of Poole (1970).

Second, output stabilization may not be the exclusive

objective of monetary policy, especially for central

banks that follows inflation targeting framework. The

focus can be the deviation of inflation from the target

or any weighted combination of output stabilization

and price stability. Therefore, the robustness of Poole

(1970) consensus is open to question for cases that

central banks have preference to other

macroeconomic outcome beyond output stabilization.

Final, monetary authorities in emerging economies

can choose both instruments rather than one. One

reason is that they are unsure about the source of

uncertainty. It is difficult to conclude whether

changes in the economy is from the real sector or the

monetary sector. It is highly likely that both monetary

shocks and real shocks have an effect on the

economy. Furthermore, in practice, the money supply

and interest rate are not necessarily competing but

they can be complementary. For instance, reserve

instrument can support interest rate instrument when

the level of financial friction is high (Sensarma–

Bhattacharyya 2016). Recently, central banks in

emerging economies have an additional task of

securing financial stability; therefore, they opt to use

reserve requirement instrument (Glocker–Towbin

2012).

Furthermore, several studies show that the use of

interest rate instrument does not always follow Poole

(1970) criteria. Higher output volatility when

targeting interest rates allows individuals and firms

more room to optimize the utility. In some cases,

interest rate can be employed because of political

pressure coped by monetary authorities (Cover–

VanHoose 2000). Particularly, monetary authorities

can lose credibility because of political pressure if

there is high degree of error in the control of reserve

instrument. This implies that interest rate instrument

can be employed even though it is suboptimal.

Small open economies also face more challenges

when deciding whether money supply or interest rate

is optimal. With interest rate parity assumption,

Gardner (1983) argued that monetary authorities in

small open economies encounter the trade-off

between money supply instrument and exchange rate

instrument when exchange rates are not fixed. When

the parity holds, it is equivalent in controlling interest

rate and exchange rate, thereby these instruments are

equivalent. In other words, monetary authorities have

two instruments at their disposal, exchange rate/

interest rate and money supply. However, there is no

general conclusion about the optimal choice based on

an ad hoc loss function that minimize sum of squares

of deviation of money supply and exchange rate from

their targets. The optimal choice of instruments

depends on the knowledge of the money demand and

money supply as well as the relative weight put on the

control of exchange rate. If monetary authorities have

perfect knowledge about money demand, interest rate

instrument is superior to reserve instrument. If they

know money supply perfectly, reserve instrument is

superior. However, when exchange rate movement is

of great concern, interest rate instrument can be

preferred even though monetary authorities

completely know the process of money supply. Under

New Keynesian framework, Singh–Subramanian

(2008) examined the superiority of money supply

instrument and interest rate instrument under

different types of shocks. Based on welfare yardstick,

they found that targeting money supply is preferred to

deal with demand (fiscal) shock whereas interest rate

is best to respond to supply (productivity) shock or

monetary (velocity) shock.

2.2 Empirical Choice of Monetary

Policy Indicator in Emerging

Economies

Empirical studies use both quantity-based indicators

such as monetary aggregates and price-based

indicators such as short-term interest rates to measure

monetary policy. Follow the seminal Sims (1972)

work, many studies use VAR-based innovations to

the growth rate of monetary aggregates as surprised

changes in monetary policy. In the 1990s, however,

many countries shifted to inflation-targeting

monetary policy (Howells–Bain 2003, Peters 2016).

The measure of monetary policy also changed, with

the focus moving onto price-based indicators.

While there is no agreement on the optimal choice

of monetary policy instrument, the prior that interest

rates are an appropriate measure of monetary policy

is popular for studies of emerging economies or Latin

America. Among many others, Furlani et al. (2010),

Sánchez-Fung (2011), De Mello–Moccero (2011),

Cermeño et al. (2012), Jawadi et al. (2014), (Aragón–

de Medeiros 2015) are studies that employ interest

rate as measure of monetary policy for investing the

performance of Taylor rule in Latin America.

However, the paucity of studies on indicator problem

results in the ambiguity of the relative effectiveness

Measures of Monetary Policy in Latin America

29

of monetary aggregates and interest rates in

measuring monetary policy.

3 METHODOLOGY AND DATA

3.1 Methodology

This paper compares the performance of different

indicators of monetary policy on two bases. First, the

monetary policy indicator should be causally related

to the objective of price stability. Second, the

preferred indicator of monetary policy should show

the dominance in fulfilling the objective of price

stability.

3.1.1 Causality Analysis

An indicator is effective when its adjustments result

in changes in targeted variables. Therefore, we can

determine the usefulness of a monetary policy

indicator by investigating its causal effect on target

variables. According to Sun–Ma (2004), if the

causality runs from instruments to prices/output, the

instruments are effective for price/output stability. By

contrast, if the causality runs from target variables to

the instrument, the instrument is considered as

endogenous. Since four Latin America countries in

the sample follow inflation-targeting framework, the

focus of the analysis is on how a monetary policy

indicator leads to inflation.

Granger (1969) causality test is a pioneering

method for examining the causality between

variables. Its VAR representation is:

01122

...

tttptpt

YYY Y

ββ β β

ε

−− −

=+ + ++ +

(1)

Where

t

Y is a vector of k endogenous variables

and

t

ε

is white noise. Since this paper investigates

the causality between monetary policy indicators and

inflation,

t

Y consists of inflation and a monetary

policy indicator.

The standard VAR copes with the stationarity and

cointegration condition. However, if variables are

integrated or cointegrated, it leads to the violation of

the standard distribution of the Wald test in VAR

model (Toda–Yamamoto 1995). To overcome this

issue, Toda–Yamamoto (1995) suggested adding the

maximum integration order

d

into the selected lag of

the standard VAR

p , then estimating the VAR

system with the surplus lag

pd+ , and finally

conducting Granger test up to standard lag

p . The

additional lag

d

ensures that the Wald test of VAR

coefficients is asymptotic. The surplus lag VAR is:

01122

...

tttpdtpdt

YYY Y

ββ β β

ε

−− +−−

=+ + ++ +

(2)

This paper employs Toda–Yamamoto (1995)

method to test the causal effect of monetary policy

indicators on inflation in Latin America. One reason

for such a choice is that variables under investigation

are unlikely to be stationary at the same level for four

Latin America. Another reason is to ensure the

comparability of the results when simultaneously

considering several countries.

3.1.2 Relationship Analysis

The literature suggests that interest rate and money

supply can provide numeric information about the

direction and size of changes in the monetary policy.

To examine the impact of these measures on inflation,

we use a VAR model of four endogenous variables as

follows:

t

Y =[DLCPI DLY DLNEER DLM1/DLM2/R] (3)

Monetary policy indicators in equation (3)

include three variables: M1, and M2 and policy rate.

Therefore, equation (3) is regressed three times, each

time with one monetary indicator. Because of

stationary condition, variables that enter the VAR

model are first difference of their logarithm,

excepting for interest rate. In particular, DLCPI,

DLY, DLNEER, DLM1, DLM2 are the first

difference of the logarithm of consumer price index,

industrial production index, nominal effective

exchange rate, M1, and M2 respectively. R is the

policy rate.

The strength of the linkage between monetary

policy indicators and inflation is analysed through

impulse response function (IRF). IRFs indicate the

direction and the magnitude of the effect of

exogenous changes in monetary policy indicators on

inflation.

It should be noted that the VAR model is

recursive with the ordering specified in Equation (3).

The given ordering implies that inflation, output, and

exchange rate have a contemporaneous effect on a

monetary policy indicator while current changes in

the monetary policy indicator causes other variables

to changes in the future. Such a recursive causal

ordering requires minimum assumptions about the

structure in the VAR model.

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

30

3.2 Data

The paper examines the performance of various

monetary policy indicators in four Latin America

countries: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico. The

study period starts at January 2002 for Brazil and

January 2000 for other countries. The sample ends at

June 2018 for all countries. We split the sample into

two subsamples to examine the influence of crisis on

the performance of monetary policy instruments. The

selected break point is June 2008.

Monetary policy indictors include both monetary

aggregates and interest rates. Monetary policy

aggregates are narrow money supply (M1), broad

money supply M2 (M2). Interest rate measure of

monetary policy (R) is Selic rate for Brazil, monetary

policy rate for Chile, central bank policy rate for

Colombia, and 91 days TIIE rate for Mexico. The data

is collected from website of corresponding central

banks.

It should be noted that four Latin America

countries adopted inflation targeting framework in

the late 1990s. Currently, Brazil has the target

inflation of 4.5% and 2% tolerance while other

countries aim for the target of 3% with 1% tolerance.

The performance of inflation stabilization is not quite

good in the region. Inflation rate are volatile,

especially at the begin of inflation targeting and after

the global financial crisis. Compared to other

countries, Brazil experienced a lengthy period of

stable inflation. These facts raise doubts about the

effectiveness of interest rate instrument in stabilizing

inflation in these countries.

4 EMPIRICAL RESULTS

4.1 Causality

This section discusses the causal relationship between

monetary policy indicators and inflation in Latin

America. The analysis is of importance because it

shows whether changes in a monetary policy

indicator lead to changes in inflation. Moreover, it

fills the weakness of correlation analysis in previous

studies. We present the results of Toda–Yamamoto

(1995) test since it accounts for the nonstationarity of

variables. As shown in Table 1, variables are not

integrated at the same level across countries. The

majority is stationary at first difference (superscript

a). Some variables are stationary at level (superscript

b).

Table 1: ADF test for the stationarity of variables.

Variable Brazil Chile Colombia Mexico

LY -7.49

*(b)

-

12.11

*(b)

-11.82

*(b)

-8.56

*(b)

LCPI -5.24

*(b)

-8.15

*(b)

-8.02

*(b)

-8.75

*(b)

LM1 -3.25

**(a)

-8.63

*(b)

-13.99

*(b)

-

16.69

*(b)

LM2 -3.57

*(b)

-8.11

*(b)

-17.09

*(b)

-

16.25

*(b)

R -4.97

*(b)

-3.05

**(a)

-4.96

*(a)

-4.68

*(a)

LNEER -7.92

*(b)

-3.11

**(a)

-9.16

*(b)

-9.21

*(b)

Source: Author’s calculation

Notes:

*

,

**

,

***

denote significance at 1%, 5%, 10%.

(a)

: unit root test at level.

(b)

: unit root test at first

difference. Lag is selected by SBIC criterion.

Table 2: The causal effect of monetary policy indicators on

price.

Before crisis Brazil Chile Colombia Mexico

R → LCPI 22.06

**

3.26 20.67

**

32.94

*

LM1→ LCPI 38.31

*

26.48

**

50.43

*

83.15

*

LM2 →

LCPI

130.76

*

26.89

*

85.72

*

10.88

After crisis

R → LCPI 11.06

*

47.6

***

12.85 57.5

***

LM1→ LCPI 0.17 27.69

**

43.86

***

71.16

***

LM2 →

LCPI

6.04 1.48 33.15

***

47.49

***

Source: Author’s estimation.

Notes:

*

,

**

,

***

denote significance at 1%, 5%, 10%.

As shown in Table 2, there is a shift in the

significance of the causality between monetary policy

indicators and price after crisis. The occurrence of the

global financial crisis leads to changes in the

significance of the interest rate instrument in two

countries, Chile and Colombia. While Colombia

copes with the loss in the causal effect of policy rate

on price, the reverse happens with Chile, whereby the

causality becomes statistically significant. For other

countries, changes in policy rate cause price to

change. Turning to monetary aggregates, the causal

effect of M1 on price is significant for Latin America

economies (except for Brazil during the post-crisis

period). Its significance does not alter during the post-

crisis period in most countries. M2 has a significant

causal effect on price in all countries excepting for

Mexico before crisis. This causality is statistically

significant for Colombia and Mexico after crisis.

Measures of Monetary Policy in Latin America

31

In summary, the recent global financial crisis has

a trivial effect on the causality between monetary

policy indicators and monetary policy objectives.

Overall, changes in both interest rate and money

supply lead to changes in prices in four Latin America

countries.

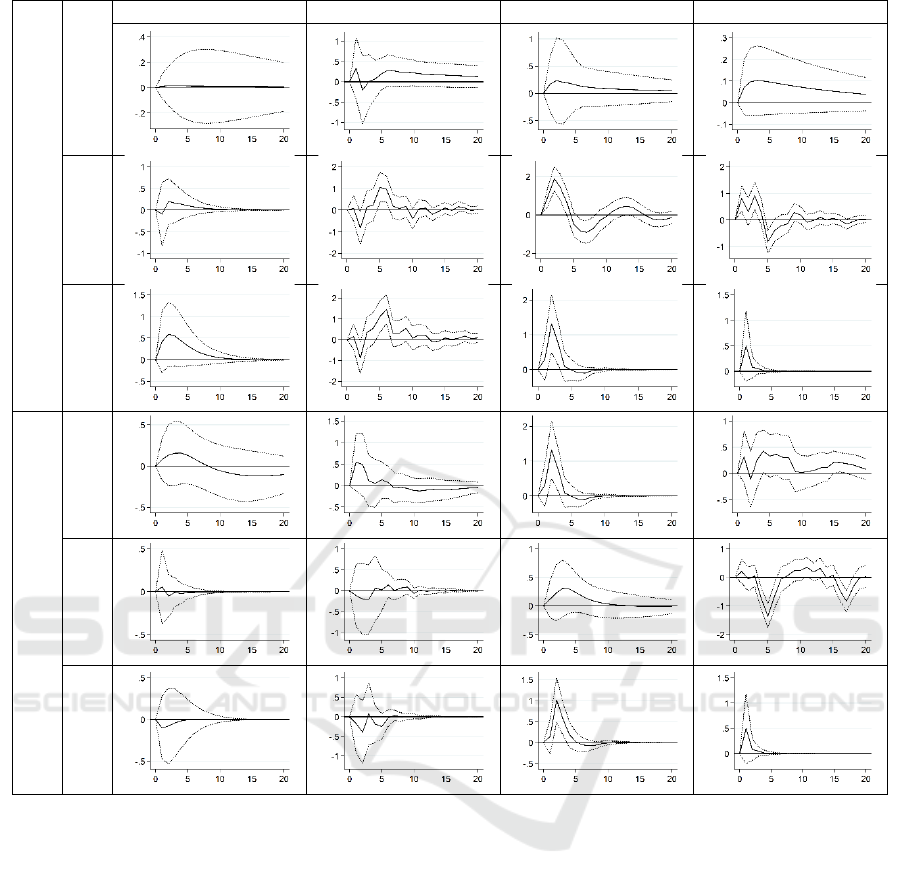

4.2 Impulse Response Analysis

We proceed by separately investigating the dynamic

effect of monetary aggregates and interest rates on

inflation (see Figure 1). Since policy rate and

logarithm of other variables have different order of

integration, we estimate recursive VAR as specified

in equation (3) by using interest rate and first

difference of other variables. Such a transform does

not affect the interpretation of the empirical results.

As shown in Figure 1, there are two panels

corresponding to the pre-crisis and post-crisis period.

Each panel indicates the response of inflation to

interest rate, M1, and M2.

The results show that interest rate shocks have

positive effect on inflation, indicating the presence of

price puzzle, a phenomenon labelled by Sims (1992).

This means that a restrictive monetary policy

constructed by raising interest rate does not lead to a

fall but a rise in inflation, which is counterintuitive.

For Brazil, the price puzzle is pronounced and

observable after the crisis while being muted before

crisis. This pattern can be a result of deconstructing

credibility of the Central Bank of Brazil (CBB).

According to Aragón–de Medeiros (2015), CBB

became less and less responsive to current and

expected inflation and eventually violated the Taylor

principle since the mid-2010. Cortes–Paiva (2017)

also pointed out that CBB follows excessively loose

monetary policy during the first administration of

Rousseff president, from 2011 to 2014. Other reason

might be the reluctance of CBB in fighting inflation

(Moura–de Carvalho 2010).

Similar results emerge for Chile, Colombia and

Mexico. It should be noted that the number of

instruments in Colombia have increased over time,

which is important for the attainment of multiple

targets such as price stability, economic growth,

financial stability, exchange rate stability, and

adequacy of international reserve. As a result, interest

rate is weak in representing monetary policy in

Colombia. For Mexico, Bank of Mexico has more

indirect influence on market interest rate before crisis.

At the beginning of inflation targeting, it uses two

instruments, Corto and minimum interest rate, to

signal the stance of monetary policy. As noted by

Garcia-Iglesias et al. (2013), overnight interbank is an

official operational target in Mexico after 2004 and it

only replaced Corto instrument after January 2008.

Corto refers to the system of target balances that

commercial banks must reserve at the central bank.

The central bank can announce a negative balance

target to signal a restrictive stance, which motivates

banks to chase for funds and increase market interest

rates. The existence of two instrument also indicates

that changes in interest rates show a part of changes

in the stance of monetary policy. After crisis,

however, the price puzzle is not persistent, reflecting

improvement in the performance of the interest rate

instrument.

The existing literature also suggests some

explanation for the existence of the price puzzle.

First, a disadvantage of a VAR model is its small

scale; therefore, it is likely that the VAR model fails

to capture important information that monetary

authorities use to forecast the movement of inflation

in the future (Sims 1992). The existing literature

(Sims 1992, Bernanke–Mihov 1998) suggests that the

inclusion of additional variables such as commodity

prices or asset prices can eliminate the problem of

price puzzle. However, this remedy is not always

effective, especially for the case of Latin America

under investigation (see Section 4.3).

Second, price puzzle can emerge because of

factors other than model misspecifications. First,

price puzzle can be a result of the effect of monetary

policy on the supply side of the economy. Interest

rates can be considered as capital cost of productive

production; thereby raising it leads to a rise in the cost

of borrowing and this cost will pass on consumers.

This implies a rise in the price level after an increase

in interest rate. If this effect dominates the effect of

demand reduction on prices, prices are higher rather

lower. Such a mechanism is also termed as cost

channel (Barth–Ramey 2001). Other reason is the

influence of information asymmetry. It is likely that

monetary authorities may have more information

about price movement than the private sector and they

will increase interest rates when expecting a rise in

the price level. However, the absence of complete or

perfect information leads to the fact that their

responses are insufficient to or too late to curb

inflation. Therefore, inflation increases rather than

fall after a rise in interest rates (Walsh 2010).

Furthermore, Latin America countries do not strictly

follow inflation targeting. This means that their

increase in interest rate is not larger than the increase

in inflation. According to Moura–de Carvalho (2010),

while Brazil and Mexico are more responsive to

inflation expectation; Chile is less responsive; and

Colombia is almost irresponsive. For Chile and

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

32

Figure 1: Inflation response to monetary policy indicators.

Colombia, the response of interest rate to inflation is

less than one-for-one. The weak inflation response

can also be a result of the high inflation expectation

of economic agents, which prolongs the process of

disinflation (Mackiewicz-Łyziak 2016).

Turning to monetary aggregates, Figure 1 shows

that inflation positively reacts to shocks to money

supply. This implies that a rise in money supply

causes inflationary pressure on the economy. Such a

response is of expected sign and is according to the

monetary theory. However, the negative response of

inflation to money supply shocks is found in Brazil

and Chile, which is counterintuitive.

Overall, the empirical results show the

ineffectiveness of monetary policy for price stability

in Latin America when measuring monetary policy by

a single indicator, either interest rates or monetary

aggregates. The existing literature suggests two

justifications for the insignificant effect of monetary

policy on prices. Firstly, the incorrect identification

leads to a dirty measure of exogenous shocks in the

system, which is less likely to happen in the paper.

Secondly, it is the choice of an inappropriate

indicators of monetary policy. The analysis of

causality and IRF provides evidence that the latter

may be an applicable explanation.

4.3 Robustness Tests

The literature (see, for instance, Sims 1992,

Bernanke–Mihov 1998) suggests that the presence of

price puzzle can be a result of the failure to

incorporate useful information for the forecast of

inflation. Therefore, we conduct a robustness test of

Before crisis

R

Brazil Chile Colombia Mexico

M1

M2

After crisis

R

M1

M2

Measures of Monetary Policy in Latin America

33

the model (3) by augmenting shocks to commodity or

oil prices. Since Latin America countries are small-

open economies, the evolution of commodity or oil

prices have impacts on domestic prices. However,

these countries are not likely to affect the price of the

world commodity or oil; therefore, shocks to these

variables are considered as exogenous. This means

that their shocks have contemporaneous effect on

domestic economic activities and changes in a

monetary policy indicator, but not the reserve. The

results (not shown, available upon request),

demonstrate that there is little difference in the

impulse response. The price puzzle is still present,

reflecting the positive effect of interest rate on

inflation. The effect of monetary supply on inflation

is positive, which is consistent with the prediction of

the monetary theory.

Another robustness test involves changing the

measure of inflation. Following Acosta-Ormaechea–

Coble (2011), we replace inflation measure in the

baseline model (equation 3) by the differential

between domestic inflation and the US inflation. This

approach is believed to isolate domestic inflation

from the effect of external factors, thereby removing

the presence of price puzzle. In this paper, we choose

US inflation because Latin America countries use US

dollar as an anchor currency. Other reason is that US

is a large economy that can affect the price of Latin

America economies, its small neighbours. We

estimate how changes in a monetary policy indicator

affect the inflation gap with and without considering

the influence of commodity or oil prices. The results

show that these changes do not solve the problem of

price puzzle and provide no general consensus about

the superiority of either policy rate or monetary

aggregates.

In summary, the paper provides evidence in

support of the argument that the price puzzle is a

result of low representative power of interest rate

other than model misspecification. To put it

differently, neither interest rate nor monetary

aggregate can summarize enough information about

changes in monetary policy.

5 CONCLUSIONS

What should be the primary indicator of monetary

policy: interest rate or some monetary aggregates? It

is a controversial issue in the analysis of monetary

policy and is limitedly investigated in emerging

economies. This paper sheds light on the usefulness

of interest rate and monetary aggregates as an overall

measure of monetary policy in four emerging

economies in Latin America. The results of causal

analysis and impulse response function demonstrate

that both policy rate and monetary aggregates explain

the movement of inflation. Moreover, monetary

aggregates dominate interest rate. There is strong

evidence suggesting the presence of price puzzle

following a positive shock to interest rate instrument.

The presence of price puzzle in Latin America

provides some crucial implications for the

implementation of the interest rate policy. As argued

by Torres (2003), interest rates must change with

larger amount when monetary authorities react to

both inflation and output gap than when they focus

exclusively on inflation. This implies that monetary

authorities have two possible options. First, they

should be more responsive to inflationary pressure.

Interest rate should be raised with larger magnitude to

create a contractionary effect on aggregate demand

and thus reducing prices. However, this approach

comes with the cost of greater variation in interest

rates, eventually increasing the volatility of expected

inflation (De Mello–Moccero 2009). Secondly,

monetary authorities should focus more on inflation

if they want to lower the degree of interest rate

volatility. This requires an increase in the dependence

for monetary authorities and substantial changes in

institutional setting for some countries in the region.

For instance, Bank of Brazil has low level of

independence and accountability (Barbosa‐Filho

2008); therefore, institutions should specify the role

of the central bank in choosing the target and

instruments as well as the penalty when the target is

not fulfilled. High level of independence is also

crucial for the maintenance of credibility, which takes

time for successful construction.

Furthermore, monetary authorities should

increase the effectiveness of forecasting inflation to

improve the performance of the interest rate policy

for price stability. When monetary authorities are

forward-looking, changes in interest rate depends on

the expectation and the forecast of inflation. If

monetary authorities systematically underestimate

the expected level of inflation, interest rates show

smaller response to changes in inflation. This results

in a reduction in the role of the interest rate as a

nominal anchor. Several tools are available for

effective management of inflation expectation of the

public: (1) obtaining greater insight into determinants

of inflation or the structure of the Phillips curve and

(2) using forward guidance to improve the

transparency of monetary policy (Mackiewicz-

Łyziak 2016).

Finally, the evidence that both monetary

aggregates and policy contains information about

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

34

changes in monetary policy suggests that a composite

measure is better than single indicator in capturing the

stance of monetary policy. Although the construction

of the composite measure is outside the scope of this

paper, this topic is deserved for deeper investigation.

It should also be noted that the paper is subjected

to some drawbacks. First, the sample is small, which

concludes only four emerging economies. Further

studies should add more countries to enrich the

information of the research sample. Second, the

parameters can be time-varying, which is out of the

scope of the paper. However, this issue should put

more emphasis in future studies.

REFERENCES

Acosta-Ormaechea, S. & Coble, D. (2011): Monetary

transmission in dollarized and non-dollarized

economies: The cases of Chile, New Zealand, Peru and

Uruguay. International Monetary Fund, Washington

DC.

Aragón, E. K. D. S. B. & De Medeiros, G. B. (2015):

Monetary policy in Brazil: evidence of a reaction

function with time-varying parameters and endogenous

regressors. Empirical Economics, 48(2), pp. 557-575.

Atkeson, A.- Chari, V. V. & Kehoe, P. J. (2007): On the

optimal choice of a monetary policy instrument.

National Bureau of Economic Research, New York.

Barbosa‐Filho, N. H. (2008): Inflation targeting in Brazil:

1999 – 2006. International Review of Applied

Economics, 22(2), pp. 187-200.

Barth, M. J. & Ramey, V. A. (2001): The cost channel of

monetary transmission. NBER macroeconomics

annual, 16, pp. 199-240.

Bernanke, B. S. & Mihov, I. (1998): Measuring monetary

policy. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(3),

pp. 869-902.

Bhattacharya, J. & Singh, R. (2008): Optimal choice of

monetary policy instruments in an economy with real

and liquidity shocks. Journal of Economic Dynamics

and Control, 32(4), pp. 1273-1311.

Cermeño, R.- Villagómez, F. A. & Polo, J. O. (2012):

Monetary Policy Rules In A Small Open Economy: An

Application to Mexico. Journal of Applied Economics,

15(2), pp. 259-286.

Cortes, G. S. & Paiva, C. A. (2017): Deconstructing

credibility: The breaking of monetary policy rules in

Brazil. Journal of International Money and Finance,

74(6), pp. 31-52.

Cover, J. P. & Vanhoose, D. D. (2000): Political pressures

and the choice of the optimal monetary policy

instrument. Journal of Economics and Business, 52(4),

pp. 325-341.

De Mello, L. & Moccero, D. (2009): Monetary Policy and

Inflation Expectations in Latin America: Long‐Run

Effects and Volatility Spillovers. Journal of money,

Credit and Banking, 41(8), pp. 1671-1690.

De Mello, L. & Moccero, D. (2011): Monetary policy and

macroeconomic stability in Latin America: The cases

of Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Mexico. Journal of

International Money and Finance, 30(1), pp. 229-245.

Furlani, L. G. C.- Portugal, M. S. & Laurini, M. P. (2010):

Exchange rate movements and monetary policy in

Brazil: Econometric and simulation evidence.

Economic Modelling, 27(1), pp. 284-295.

Garcia-Iglesias, J. M.- Muñoz Torres, R. & Saridakis, G.

(2013): Did the Bank of Mexico follow a systematic

behaviour in its transition to an inflation targeting

regime? Applied Financial Economics, 23(14), pp.

1205-1213.

Gardner, G. W. (1983): The choice of monetary policy

instruments in an open economy. Journal of

International Money and Finance, 2(3), pp. 347-354.

Glocker, C. & Towbin, P. (2012): Reserve Requirements

for Price and Financial Stability-When are they

effective? International Journal of Central Banking,

8(1), pp. 65-114.

Granger, W. J. C. (1969): Investigating causal relations by

econometric models and cross-spectral methods.

Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, pp.

424-438.

Howells, P. & Bain, K. (2003): Monetary Economics:

Policy and its Theoretical Basis. Palgrave Macmillan,

New York.

Jawadi, F.- Mallick, S. K. & Sousa, R. M. (2014): Nonlinear

monetary policy reaction functions in large emerging

economies: the case of Brazil and China. Applied

Economics, 46(9), pp. 973-984.

Mackiewicz-Łyziak, J. (2016): Central bank credibility:

determinants and measurement. A cross-country study.

Acta Oeconomica, 66(1), pp. 125-151.

Moura, M. L. & De Carvalho, A. (2010): What can Taylor

rules say about monetary policy in Latin America?

Journal of Macroeconomics, 32(1), pp. 392-404.

Peters, A. C. (2016): Monetary policy, exchange rate

targeting and fear of floating in emerging market

economies. International economics and economic

policy, 13(2), pp. 255-281.

Poole, W. (1970): Optimal choice of monetary policy

instruments in a simple stochastic macro model. The

Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(2), pp. 197-216.

Romer, C. D. & Romer, D. H. (2004): A New Measure of

Monetary Shocks: Derivation and Implications. The

American Economic Review, 94(4), pp. 1055-1084.

Sánchez-Fung, J. R. (2011): Estimating monetary policy

reaction functions for emerging market economies: The

case of Brazil. Economic Modelling, 28(4), pp. 1730-

1738.

Sensarma, R. & Bhattacharyya, I. (2016): Measuring

monetary policy and its impact on the bond market of

an emerging economy. Macroeconomics and Finance

in Emerging Market Economies, 9(2), pp. 109-130.

Sims, C. A. (1972): Money, income, and causality. The

American Economic Review, 62(4), pp. 540-552.

Sims, C. A. (1992): Interpreting the macroeconomic time

series facts: The effects of monetary policy. European

Economic Review, 36(5), pp. 975-1000.

Measures of Monetary Policy in Latin America

35

Singh, R. & Subramanian, C. (2008): The optimal choice of

monetary policy instruments in a small open economy.

Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne

d'économique, 41(1), pp. 105-137.

Sun, H. & Ma, Y. (2004): Money and price relationship in

China. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business

Studies, 2(3), pp. 225-247.

Toda, H. Y. & Yamamoto, T. (1995): Statistical inference

in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated

processes. Journal of econometrics, 66(1-2), pp. 225-

250.

Torres, A. (2003): Monetary policy and interest rates:

evidence from Mexico. The North American Journal of

Economics and Finance, 14(3), pp. 357-379.

Walsh, C. E. (2010): Monetary theory and policy. 3

rd

. MIT

press, Massachusetts.

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

36