A Study on Gamification Effectiveness

Petar Cvetkovic

1

, Charly Harbord

2 a

and Helmut Hlavacs

1 b

1

University of Vienna, Faculty of Computer Science, Vienna, Austria

2

Abertay University, School of Design and Informatics, Faculty of Games and Arts, Dundee, Scotland

Keywords:

Gamification, Effectiveness, Education, Feedback.

Abstract:

Studies have shown that gamification increases motivation and user experience when it comes to a certain

behavior or completing a process. Gamification is often deeply associated with na

¨

ıve animations and stylized

text. This paper addresses the effect that visual representation has on the motivation of a subject by measuring

their motivation after completing a mundane process, with both entertaining gamification elements as well as

gamification elements presented in plain text. For the purposes of this study a within subject design was used

to gather data. Participants completed the same mundane task three times, once without any gamification ele-

ments, once with pragmatic feedback and once with entertaining feedback. After completion, the participants

filled out the same Likert scale survey. The results, evaluated using the Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks test method,

indicated that there was not a significant difference in user motivation between the visually stylized and plain

text feedback. If conducted on a larger scale, this discovery could lead to a reduction in both time and cost for

gamification development.

1 INTRODUCTION

Gamification is the use of game design elements in

non-game settings to engage participants and encour-

age desired behaviors (Deterding et al., 2011) The

premise is that “to create an effect in non-game fields

by applying the game mechanics and game thinking

which make games fun; for example points, level-

up, ranking, achievements, competition, and rewards”

(Park and Bae, 2014). Gamification elements have

been used broadly in many different branches with

the goal to make processes more entertaining and eas-

ier to grasp (Deterding et al., 2011). However, it is

worth noting that “entertaining” motivational tricks

are subjective and are very much dependent on the

user’s perspective (Kuo and Chuang, 2016). In order

to motivate users; gamification inserts game mechan-

ics and dynamics into non-game contexts (de Marcos

et al., 2014). Within the field of motivation, they can

be seen to be two main branches: extrinsic and in-

trinsic. Extrinsic motivation refers to an action be-

ing completed with the knowledge that there will be

some defined reward at the end. Intrinsic motivation

however, refers to an action that is completed purely

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7079-852X

b

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6837-674X

for the joy of that action. It is this combination of

the intrinsic motivation of gameplay and educational

activities, which would normally be associated with

extrinsic motivation, that is of great interest to both

researchers and educators. Additionally, gamification

by way of increasing intrinsic motivation also has the

potential to improve engagement via the medium of

flow (Hamari, 2013; Huotari and Hamari, 2012; Csik-

szentmihalyi, 2009; Deci and Ryan, 1985). The re-

search described in this paper was designed as a case

study to investigate whether the visual presentation

of feedback has influence on the intrinsic motivation

when completing a process. The hypothesis being:

“Does visual representation improve user motivation

or just improve the over-all impression of the task?” If

the user motivation does not change drastically, then

the development time and cost of gamification ele-

ments would therefore be reduced. At present, within

the gamifiaction process a large proportion of time is

devoted to the design of visual elements. The efficacy

of gamification was measured by conducting a within

subject study with 10 participants and then evaluat-

ing the results using the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

method.

This paper details the results of the experiment

carried out at the University of Vienna in 2019. The

remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Sec-

236

Cvetkovic, P., Harbord, C. and Hlavacs, H.

A Study on Gamification Effectiveness.

DOI: 10.5220/0009340102360244

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 2, pages 236-244

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

tion 2 provides information about studies which prove

that gamification overall improves the user motiva-

tion; Section 3 provides a description of the experi-

ment; Section 4 shares the results of findings; Sec-

tion 5 shows a detailed interpretation of the results

and Section 6 summarizes the findings and discusses

future work.

2 RELATED WORK

There have been an increasing number of scientific

papers that have described the analysis and applica-

tion of gamification and benefits from it. There has

been heavy focus on measuring and showing how

gamification elements improve user motivation and

according to (Vesa, 2017) more than 50 percent of the

organizations who manage an innovative process will

gamify their business. The subsections below serve as

examples for the application of gamification in differ-

ent professional situations.

2.1 Gamification in Education

Gamification plays a huge role in education. Games,

in any form, increase motivation through engagement,

participation, loyalty and competition (Alsawaier,

2018). The premise being that by employing the ‘en-

tertaining’ aspects of games and gameplay to a or-

dinary educational activities the student motivation

to complete those actions should increase (Kuo and

Chuang, 2016). According to Chou (Chou, 2019):

“...gamification is one of the methods that motivates

students to actively participate in class, learn through

entertainment by playing with their colleagues and

emphasize on the positive competition and also, to

make learning fun”. Gamification of within the field

education is often implemented within the classroom

setting during class time. One benefit of within class

use is that the students are able to follow their own

progress and achievements via instantaneous feed-

back allowing for an increase in motivation and en-

gagement (Kapp, 2012; Simoes et al., 2013)

2.2 Gamification in Medicine

Gamification is breaking the barriers of medicine by

using elements to increase motivation to become a

blood donor. “...development of applications that can

facilitate users to motivate each other doing voluntar-

ily and routinely blood donors, by gamification con-

cept.” (Prasetiantowibowo and Lusi-Ani, 2017).

2.3 Gamification in Sport

Gamification also influences the world of sports. As

stated in Chou (Chou, 2019): “people find it diffi-

cult to get time and interest for doing sports activ-

ities in the form of recreational sport...gamification

principles are used to enhance the experience in those

activities.” A good example of health and gamifica-

tion combined is the “Nike+ App”. This is a system

that calculates and transmits distance run and calo-

ries burned of a person by the utilization of a spe-

cially designed sensor attached to the running shoe

that syncs data with an iPod. By default, it promotes

social fun when used with friends, and aids the user

to plan, share, and complete exercise plans through

an app (Koivisto and Hamari, 2014). Feeding back to

the question that the paper aims answers of whether

or not the visual presentation of feedback elements

matter. Would the “Nike+ App” users run the same

distance if the feedback was presented in plain text,

or do the animation and pleasing visual design have a

motivational effect on performance?

3 DESCRIPTION OF THE

EXPERIMENT

The purpose of the research study was to explore the

impact of the representation of a single gamification

element – for the purposes of this study the gamifi-

cation element used was gamified feedback - on the

user’s intrinsic motivation and excitement in complet-

ing a mundane process. To conduct the study, a mun-

dane process was created and remained constant on

the left side of the screen, while the different feed-

back types changed on the right side.

3.1 Hypotheses

• Null hypotheses: The type of feedback has no in-

fluence on the intrinsic motivation of completing

a process.

• Alternate hypotheses 1: Showing only facts with-

out gamification elements motivate completing

the process less than using gamified feedback.

• Alternate hypotheses 2: Using a pragmatic gam-

ified feedback motivates completing the process

less (or more) than using entertaining feedback.

3.2 Experimental Participants

The study was conducted on June/July 2019. There

were no specific categories. The participants were

A Study on Gamification Effectiveness

237

taken from the general public. There were no restric-

tions to who the participants should be, the more di-

verse, the better. Among the participants, 6 out of 10

were female and 4 out of 10 were male. The average

age of the respondents were 22 years old.

3.3 Game Development

In order to develop the counting game (described in

the following section) and evaluate the experimental

results we used a number of software tools. “Bal-

samiq Mockups“

1

was used to draw the process and

feedback mock-ups during the game design. A screen

shot can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Screenshot of Balsamiq Mockups.

The game was developed using the popular game

engine “Unity 3D“

2

. Unity 3D is a general purpose

game engine which allows the launch of games on a

multitude of platforms, in our case the chosen plat-

form was Windows, a screen shot is shown in Figure

2.

Figure 2: Screenshot of Unity.

Finally, “IBM SPSS Statistics“

3

has been used to

derive statistical results.

1

https://balsamiq.com/

2

https://unity.com/

3

https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-

software

3.4 The Counting Game

For the purposes of the investigation, a mundane pro-

cess with three different variations of feedback was

developed and a questionnaire was designed. In the

game, the screen is split in the middle. The left side

displayed the mundane process and stayed constant

throughout. The right-side displayed the feedback

and changed depending on the feedback type. The

mundane process was defined to be subtracting the

number 11 from another given start number, as many

times as possible within 60 seconds. It was clear

that such a task soon becomes tedious and is gen-

erally considered not to be fun. The counting game

offered three levels, each of them representing a dif-

ferent feedback type. Figure 3 shows the game’s start

menu. At this point, the player can select one of three

levels of the game, each level representing one of the

three possible feedback types. In the following each

of the feedback types is described.

Figure 3: Main menu screen.

3.4.1 Level 1: No Feedback

There is no main goal or narrative of the game in this

level, the subject merely needed to answer as many

questions correctly as they could within 60 seconds.

The right-side of the screen shows a countdown timer

indicating the remaining time, correct answer count

and the correct/wrong text. Also, the decision was

made to not use sound effects. Figure 4 shows the

intro scene explaining how to play the game for the

no-feedback level. Figure 5 shows how the game pro-

gresses in the no-feedback level. The left upper im-

age, shows how the game starts, to the right, one an-

swer has been answered correctly. On the left lower

image, the game is shown after a number of correct

answers. On the lower right image, the case of a

wrong answer is shown.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

238

Figure 4: Intro scene no feedback.

Figure 5: Scenes from no feedback.

3.4.2 Level 2: Pragmatic Feedback

This level includes the introduction of a goal: to save

a turtle by leading it to the safety of the sea. The

goal can be achieved by reaching a total of 20 points.

Every correct answer counts as one point, and every

wrong answer reduces the score by a point. Depend-

ing on the amount of points, the turtle moves closer

to or further away from the sea, which is also graphi-

cally shown on the right feedback screen. After three

correct answers in a row, a double points bonus is

awarded. However, the bonus disappears if the user

does not submit another correct answer within 4 sec-

onds, or if the next answer is wrong. The feedback

is presented as plain text. There are also added sound

effects for the correct and wrong answers.

Due to the narrative, this level is considered to be

gamified, though only to a bare minimum. Depictions

of successes or failures are not exaggerated. Instead,

the additional motivation is given mainly due to the

narrative, something that gives meaning to the pro-

cess. Figure 6 shows the intro scene of the game for

pragmatic feedback, describing the game functions.

Figures 7 and 8 show a progression of this level. Fig-

ure 7 depicts the feedback of correct answers, while

Figure 8 shows the conquences of submitting wrong

answers or even failing to achieve the level goals.

Figure 6: Intro Scene from pragmatic and entertaining feed-

back.

Figure 7: Scenes from pragmatic feedback.

3.4.3 Level 3: Entertaining Feedback

The goal and mechanics of this level are kept the same

as the pragmatic feedback level. However, the feed-

back differs in two ways: firstly, it utilizes colorful

animation, and more sound effects. Secondly, the cre-

ation of tangible achievements in the form of medals

which can be gained by getting three, five and ten cor-

rect answers in a row. Sound effects are added for

typing, the correct answer, the wrong answer, bonus,

bonus loss, medals, and general background music.

The introduction to the ‘game’ was kept the same as

pragmatic feedback (Huotari and Hamari, 2012), as

depicted in Figure 6.

This level is considered to be strongly gamified, it

looks and feels like a computer game made for enter-

tainment purposes only. The gamification of feedback

here is exaggerated, and represents an extreme “sugar

coating” of the mundane counting process. Figure

[9] shows the feedback of correct answers, providing

Figure 8: Scenes from pragmatic feedback.

A Study on Gamification Effectiveness

239

multiple positive reactions. Figure 10 on the upper

row shows the feeback for wrong answers or failure,

the rows below show feedback for success including

streaks and medals.

Figure 9: Scenes from childish feedback.

Figure 10: Scenes from childish feedback.

4 EXPERIMENTAL EVALUATION

Data was collected in person and there were no spe-

cial conditions required for running the project. A

within subject study design was used as this allowed

for the same users to test all conditions, complete

the process three times and fill out the same ques-

tionnaire after each completion. The feedback or-

der was randomized for preventing any particular or-

dering of introducing a bias to the results. The sur-

vey answers were rated with a Likert scale utilizing

5 levels: strongly disagree, weakly disagree, neu-

tral, weakly agree, and strongly agree. Values be-

tween -2 (strongly disagree) to +2 (strongly agree)

were awarded. The survey questions are due (Deter-

ding et al., 2011) and formulated in a positive way.

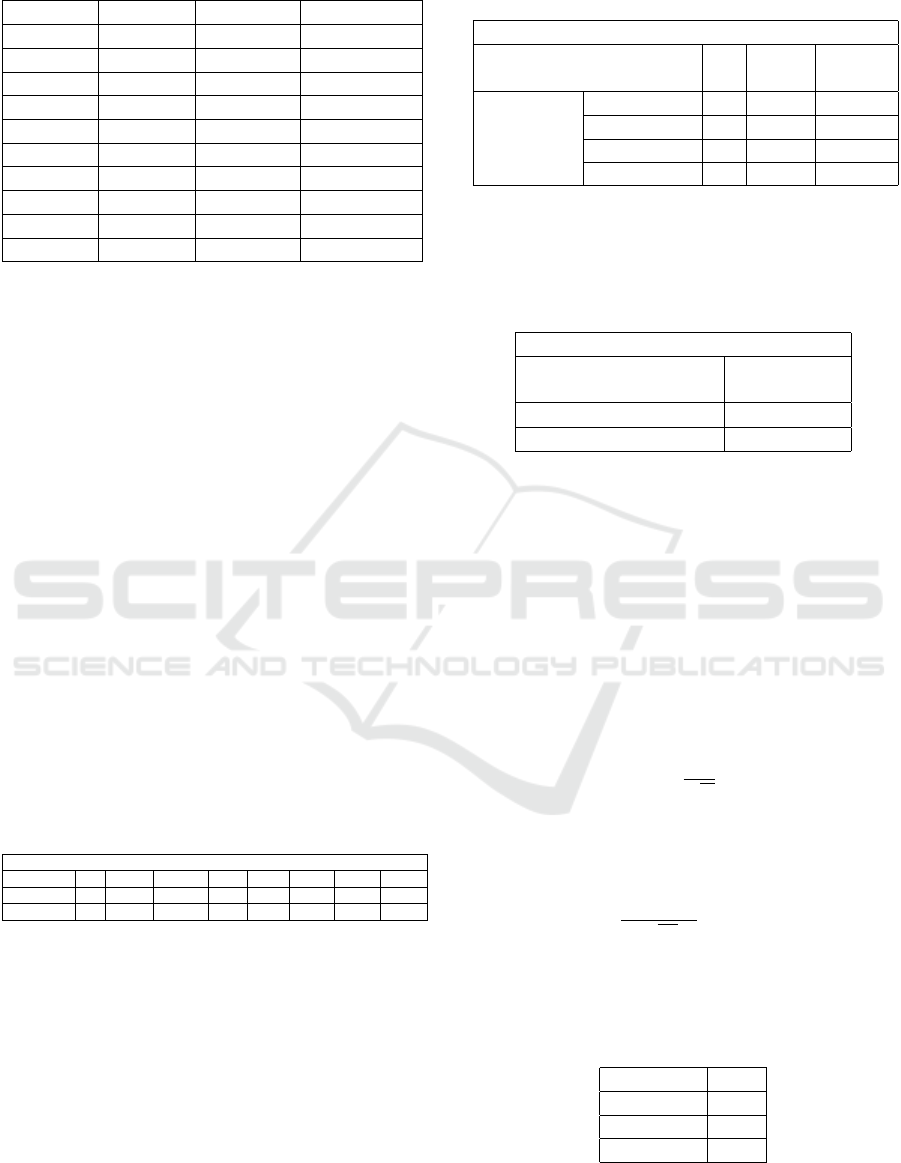

They can be found in the Table 1.

Table 1: List of questions from the survey.

Please rate the following statements.

1 Completing the process was fun

2 I felt excited

3 I never felt bored

4 I would complete the process again

5 I felt like a MATH GENIUS

6 I felt like I was really saving the turtle

7 I felt motivated to get as many correct

answers as possible

8 Answering correctly felt rewarding

9 I double checked my answer to make

sure I don‘t answer wrong

10 I forgot I was doing math

4.1 Experimental Results

A Wilcoxon signed-ranks test were used for result

evaluation, because the within subject design de-

mands that the same subjects test multiple times, and

it results in paired samples. The Wilcoxon signed-

rank test is a non-parametric hypothesis test decid-

ing whether two related samples stem from the same

population or not (Wilcoxon, 1945). Data comes in

pairs, and the null-hypothesis is that they come from

the same population. Each pair is chosen randomly

and independently,

To test the hypotheses, the Wilcoxon signed ranks

test was executed three times. First the “No feed-

back“ and “Pragmatic feedback” results were com-

pared. Followed by “no feedback” and “Entertaining

feedback”, and finally “Pragmatic feedback” and “En-

tertaining feedback”. The survey consists of 10 ques-

tions; for each question, the sum of values from all

participants was calculated, which resulted in 10 spe-

cific values - one value for each question. So, the sum

of all participants ratings for one answer was viewed

as one score. This in return gives 10 answers for each

feedback type, and the difference between them are

compared. Results were calculated using the SPSS

statistics tool. Significance level alpha for a Wilcoxon

signed ranks test was 0.05.

In order for there to be a significant difference be-

tween two median values, the p value has to be less

than significance level value, and if it is, the null hy-

pothesis which states that there is no difference is

rejected. The total scores that were calculated are

shown in Table 2, (Park and Bae, 2014).

Though for a Wilcoxon singed-ranks test an in-

terval scale is recommended, for within-pair compar-

isons an ordinal scale is sufficient. We can thus sub-

mit the data from Table 2 to this test.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

240

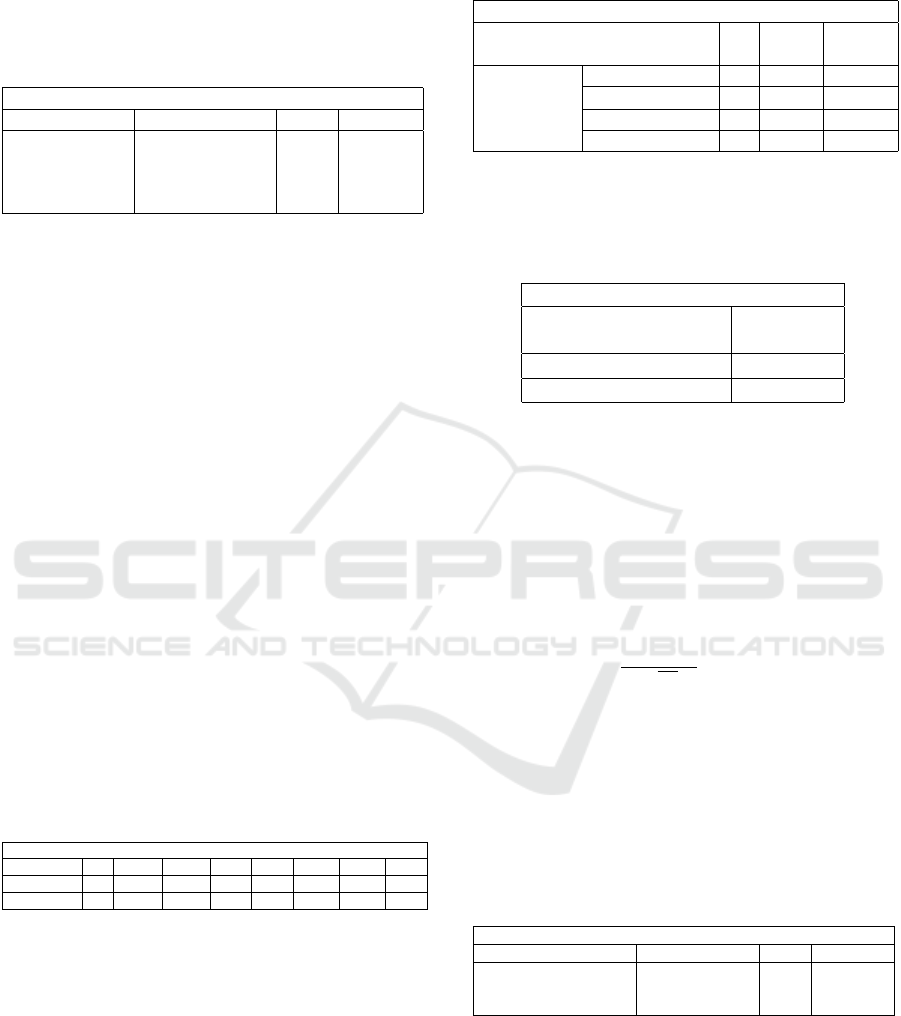

Table 2: Sum of scores for each question of the survey.

Question No feedb Pragmatic Entertaining

1 2 6 8

2 1 12 8

3 3 10 9

4 -5 6 4

5 -4 -5 -3

6 -11 -11 -1

7 10 16 12

8 -2 13 10

9 -11 -11 -10

10 -6 -6 -7

4.2 No Feedback vs. Pragmatic

Feedback

In this section we compare the results from “No feed-

back” to those of “Pragmatic feedback”. The null hy-

pothesis and its alternative are given by the following

statements:

Null Hypothesis: The type of feedback has no influ-

ence on the intrinsic motivation of completing a pro-

cess.

Alternative 1: Only facts without gamification ele-

ments motivate completing the process less than gam-

ified feedback. (the type of feedback HAS influence

on intrinsic motivation of completing a process)

Looking at the descriptive statistics shown in Ta-

ble 3, we can see that the mean value of all answers

for “No feedback” is negative (-2.30) and positive

(3.00) for the “Pragmatic feedback”, which already

shows that there is a difference between the two feed-

back types.

Table 3: Descriptive Statistics for “No feedback” and “Prag-

matic feedback”, including 25th, 50th (median), and 75th

percentiles.

Descriptive statistics

N Mean SDev Min Max 25th 50th 75th

No fb 10 -2.30 6.533 -11 10 -7.25 -3.00 2.25

Pragmatic 10 3.00 10.296 -11 16 -7.25 6.00 12.25

If we pay attention to the ranks shown in Table 4,

we notice that there is only one negative rank, mean-

ing only one from ten questions was in favor of “No

feedback“, six of them were in favor of “Pragmatic

feedback“ and three of them were tied.

Finally looking at the actual test statistics as de-

picted in Table 5, we notice that the Z value is -2.201

and the p value is 0.028.

As already stated, if the p value is smaller than the

alpha value, we reject the null hypothesis. In our case

0.028 is in fact smaller than 0.05 which means that

the type of feedback HAS influcence on the intrinsic

Table 4: Ranks table for “No feedback” and “Pragmatic

feedback”.

Ranks

N

Mean

Rank

Sum of

Ranks

Pragm. fb-

No fb

Neg. Ranks 1

a

1.00 1.00

Pos. Ranks 6

b

4.50 27.00

Ties 3

c

Total 10

a. Pragmatic fb < No fb

b. Pragmatic fb > No fb

c. Pragmatic fb = No fb

Table 5: Test statistics for ”No feedback” and ”Pragmatic

feedback”.

Test Statistics

a

Pragmatic fb

- No fb

Z -2.201

b

Asymp. Sig. (2-Tailed) 0.028

a. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

b. Based on negative ranks.

motivation of completing a process. So we reject the

null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis.

We can conclude that a Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks

test indicated that only facts without gamification ele-

ments motivate completing the process less than gam-

ified feedback. Thus the type of feedback HAS influ-

ence on the intrinsic motivation of completing a pro-

cess.

To take this a step further, we can calculate the

effect size by using the following formula:

r = |

Z

√

N

|.

The formula includes the Z value and N representing

the number of samples which is 10 for each group,

which means 20.

r = |

(−2.201)

√

20

| = 0.4921.

Based on the following effect size interpretations as

shown in Table 6 we can conclude that the effect size

is medium but very close to being large.

Table 6: Cohen’s effect size table.

Effect size r

Small 0.10

Medium 0.30

Large 0.50

We conclude that the participants enjoyed the

pragmatic feedback more than no feedback. Finally,

A Study on Gamification Effectiveness

241

the hypothesis test summary from SPSS statistics tool

is shown in Table 7, including the decision about the

null hypothesis.

Table 7: Hypothesis test summary for “No feedback” vs.

“Pragmatic feedback”.

Hypothesis Test Summary

Null Hyp Test Sig. Decision

Median of Related-Samples 0.028 Reject

differences btw Wilcoxon null

No fb and Signed Rank hypoth.

Pragm. fb is 0 Test

The significance level is 0.05.

4.3 No Feedback vs. Entertaining

Feedback

There was no real need to test the “No feedback” with

“Entertaining feedback” but for checking consistency

it was also carried out, as it might give some interest-

ing insight. The hypothesis remains the same:

Null Hypothesis: The type of feedback has no influ-

ence on the intrinsic motivation of completing a pro-

cess.

Alternative 1: Only facts without gamification ele-

ments motivate completing the process less than gam-

ified feedback. (the type of feedback HAS influence

on intrinsic motivation of completing a process)

The mean value of all answers for “No feedback“

is the same as before: negative (-2.30) and we can

see that the “Entertaining feedback“ has the same

mean value (see Table 8) as the “Pragmatic feed-

back“: positive (3.00) for the “Pragmatic feedback“,

which makes it interesting for the comparison be-

tween “Pragmatic“ and “Entertaining“ feedback.

Table 8: Descriptive Statistics for “No feedback” vs. “En-

tertaining feedback”.

Descriptive statistics

N Mean SDev Min Max 25th 50th 75th

No fb 10 -2.30 6.533 -11 10 -7.25 -3.00 2.25

Childish fb 10 3.00 7.732 -10 12 -4.00 6.00 9.25

The resulting ranks (see Table 9) from “Entertain-

ing feedback“ performed a lot better than “Pragmatic

feedback“ with nine positive and one negative ranks,

meaning only one from ten questions was in favor of

“No feedback“ and all the rest were in favor of “En-

tertaining feedback“.

A conclusion can already be drawn that there is

a significant difference between entertaining and no

feedback, but to verify, it was noticed that the Z value

is -2.608 and the p value is 0.009, which means that

p is much smaller than alpha (0.05) and the null hy-

pothesis is rejected, as shown in Table 10.

Table 9: Ranks table for “No feedback” vs. “Entertaining

feedback”.

Ranks

N

Mean

Rank

Sum of

Ranks

Childish fb-

No fb

Negative Ranks 1

a

2.00 2.00

Positive Ranks 9

b

5.89 53.00

Ties 0

c

Total 10

a. Entertaining fb < No fb

b. Entertaining fb > No fb

c. Entertaining fb = No fb

Table 10: Test statistics for “No feedback” vs. “Entertaining

feedback”.

Test Statistics

a

Childish fb

- No fb

Z -2.608

b

Asymp. Sig. (2-Tailed) 0.009

a. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

b. Based on negative ranks.

We can conclude that a Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks

test indicated that seeing only facts without gamifi-

cation elements motivate completing the process less

than gamified feedback. Thus the type of feedback

HAS influence on the intrinsic motivation of complet-

ing a process.

The effect size for “Entertaining feedback“ vs.

“No feedback“ is

r = |

(−2.608)

√

20

| = 0.4721.

This means that the effect size is medium, but we can

also see that the effect size is actually smaller than

the one from “Pragmatic feedback“, already indicat-

ing that going from pragmatic to entertaining might

not necessarily result in an increased motivation.

Finally, the hypothesis test summary from SPSS

is shown in Table 11.

Table 11: Hypothesis test summary for “No feedback” vs.

“Entertaining feedback”.

Hypothesis Test Summary

Null Hypothesis Test Sig. Decision

Median of diffs. Related-Samples 0.009 Reject

between No fb and Wilcoxon Signed the null

Entertaining fb equals 0 Rank Test hypothesis

Asymptotic significances are displayed.

The significance level is 0.05.

4.4 Pragmatic Feedback vs.

Entertaining Feedback

Finally, we compare the two gamification level “Prag-

matic feedback” vs. “Entertaining feedback”. Null

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

242

hypothesis and alternative are given in the following

statements:

Null Hypothesis: “Pragmatic feedback” motivates

completing the process the same as “Entertaining

feedback”.

Alternative 1: “Pragmatic feedback” motivates com-

pleting the process less (or more) than “Entertaining

feedback”.

Both feedback types were compared with “No

feedback” and the mean values were the same, but

“Entertaining feedback” did a lot better on the ranks,

and “Pragmatic feedback” had a bigger effect size.

Comparing both results might shed light on the ques-

tion whether there is a significant difference between

the two feedback types according to the participants.

As demonstrated previously, when comparing both

feedback types to “No feedback”, the mean value of

all answers for “Pragmatic feedback” and “Entertain-

ing feedback” are the same (3.00), see Table 12. The

minimum value of pragmatic was -11, and -10 for

entertaining, and maximum values are 16 and 12 for

pragmatic and entertaining respectfully. The descrip-

tive statistics are still ambiguous, which is why it was

decided to proceed to the actual Wilcoxon signed-

ranks test results.

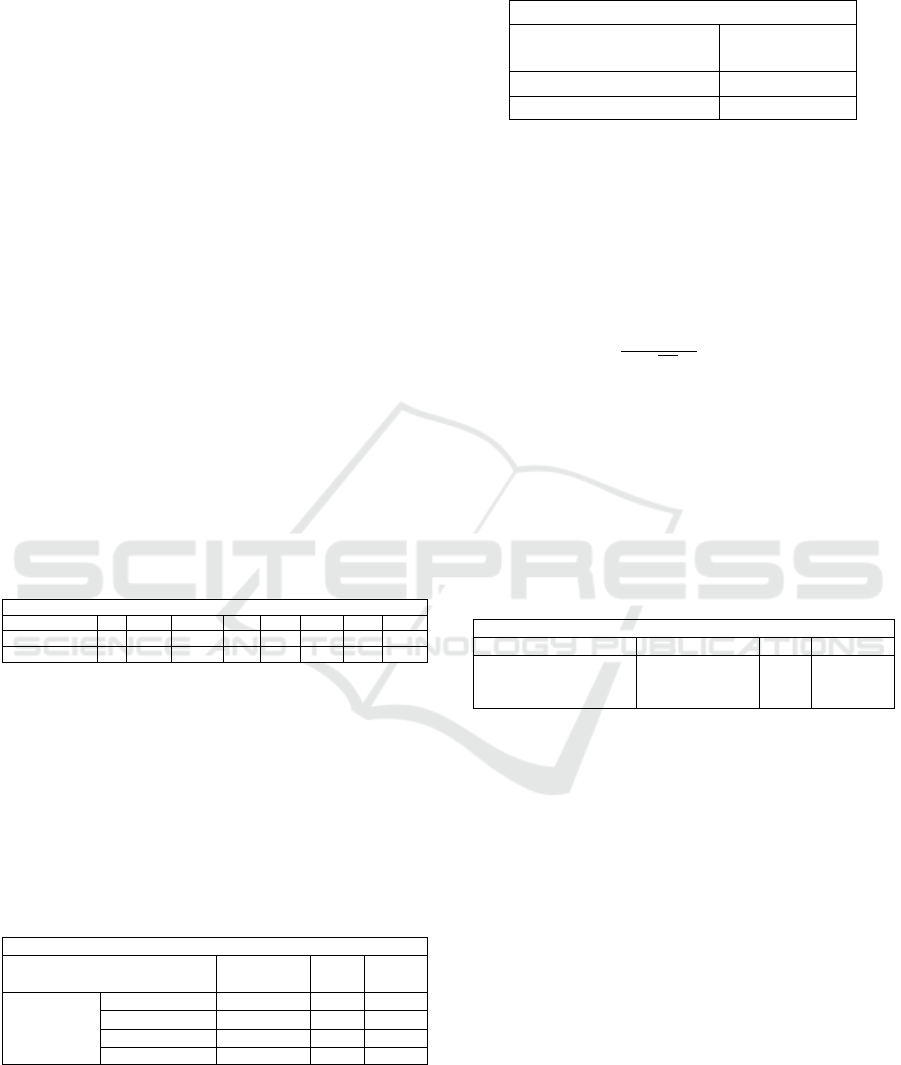

Table 12: Descriptive Statistics for “Pragmatic feedback”

vs. “Entertaining feedback”.

Descriptive statistics

N Mean SDev Min Max 25th 50th 75th

Pragmatic fb 10 3.00 10.296 -11 16 -7.25 6.00 12.25

Entertaining fb 10 3.00 7.732 -10 12 -4.00 6.00 9.25

From a total of 10 questions, 6 of them were in

favor of the pragmatic feedback and 4 of them were

in favor of the Entertaining feedback (see Table 13).

This is very interesting, because it could be assumed

that the inclusion of animation, sound effects and

graphical presentation would be more appealing than

plain text, but it appears that the pragmatic feedback

performed better.

Table 13: Ranks table for “Pragmatic feedback” vs. “Enter-

taining feedback”.

Ranks

N

Mean

Rank

Sum of

Ranks

Childish fb-

Pragmatic fb

Negative Ranks 6

a

5.50 33.00

Positive Ranks 4

b

5.50 22.00

Ties 0

c

Total 10

a. EntertainingFeedback¡ PragmaticFeedback

b. EntertainingFeedback¿ PragmaticFeedback

c. EntertainingFeedback = PragmaticFeedback

Our Z value is -0.564 and the p value is 0.573

as shown in Table 14. 0.573 is bigger than 0.05

which means that we retain the null hypothesis and

Table 14: Test statistics for “Entertaining feedback” vs.

“Pragmatic feedback”.

Test Statistics

a

Childish fb

- Pragmatic fb

Z -0.564

b

Asymp. Sig. (2-Tailed) 0.573

a. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test

b. Based on negative ranks.

that “Pragmatic feedback” motivates completing the

process in the same way as “Entertaining feedback”.

Even more, when considering the ranks we can con-

clude that the “Pragmatic feedback” actually per-

formed better than the “Entertaining feedback.” The

effect size is calculated to be

r = |

(−0.564)

√

20

| = 0.1261.

The effect size r is thus small, close to non-existent.

We can conclude that subjects did not experience sig-

nificant difference in intrinsic motivation for complet-

ing the process when it was presented in plain text

versus entertaining graphics.

Finally, the hypothesis test summary from SPSS

is shown in Table 15.

Table 15: Hypothesis test summary for ”Pragmatic feed-

back” vs. ”Entertaining feedback”.

Hypothesis Test Summary

Null Hypothesis Test Sig. Decision

Median of diffs. Related-Samples 0.573 Retain

betw. Pragm. fb and Wilcoxon Signed the null

Entertaining fb equals 0 Rank Test hypothesis

Asymptotic significances are displayed. Significance level is 0.05.

5 DISCUSSION

As previously noted, there are already a number of

studies have been conducted showing that a mundane

process becomes easier to complete with introduction

of gamification elements. The results of this research

mirror those that have gone before, with our partici-

pants indicating that “No feedback” performs signifi-

cantly worse than pragmatic or entertaining.

It was intriguing to find out that visual elements

do not play a role in motivation. It was previously

stated that “Entertaining feedback” would outperform

“Pragmatic feedback”, but our results have shown that

the motivation does not significantly change depend-

ing on the visuals. The implementation of “Entertain-

ing feedback” took more than twice the time of the im-

plementation of “Pragmatic feedback” and “No feed-

back” combined. Since our results show that this ad-

A Study on Gamification Effectiveness

243

ditional implementation effort does not improve par-

ticipant motivation, it makes sense to save this effort

in favor of other aspects, like logging more data, or

increasing the length of the game.

It is also interesting to note that some participants

really focused on the sound effects. “Entertaining

feedback” had better sound effects, but pragmatic had

a distinct “TRUE” or “FALSE” sound effects which

the subjects reported finding really helpful. One of

the participants had a notable comment for “No feed-

back”. The participant kept answering incorrectly

without noticing, because their attention was not on

the visual feedback, but the sound feedback, which

is missing in the “No feedback” level. The comment

was: “The problem was I did not hear I was wrong!”.

It can be said that whilst gamified feedback elements

are important and improve user motivation, the way

that they are presented does not make a drastic differ-

ence.

5.1 Limitations of the Study

The main limitation of this approach was that the

study was the amount of people reached who partici-

pated. It was not possible to reach a wide variety of

ages, professions etc. For example, it would be inter-

esting to see how an 8-year-old would react to doing

math in order to save the turtle.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper, the value of the gamification of feedback

was addressed together with the importance of visual

presentation. Our main contribution is that users are

not significantly more motivated to complete a mun-

dane process when feedback is presented in an enter-

taining way rather than as plain text.

REFERENCES

Alsawaier, R. (2018). The effect of gamification on motiva-

tion and engagement. International Journal of Infor-

mation and Learning Technology Vol. 35 No. 1, pages

pp. 56–79.

Chou, Y. (2019). Actionable gamification: Beyond points,

badges, and leaderboards. Packt Publishing Ltd.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow. Harper and Row., New

York.

de Marcos, L., Domiguez, A., Saenz-de Navarrete, J., and

Pages, C. (2014). An empirical study comparing gam-

ification and social networking on e-learning. Com-

puters & Education 75, pages pp.82–91.

Deci, E. and Ryan, R. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-

determination in human behavior. Plenum, New York.

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., and Nacke, L. (2011).

From game design elements to gamefulness: defin-

ing gamification. In 15th International academic

MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media en-

vironments., pages pp. 9–15.

Hamari, J. (2013). Transforming homo economicus into

homo ludens: A field experiment on gamification in

a utilitarian peer-to-peer trading service. Electronic

Commerce Research and Applications 12(4), pages

pp.236–245.

Huotari, K. and Hamari, J. (2012). Defining gamification

- a service marketing perspective. In The 16th Inter-

national Academic MindTrek Conference., pages pp.

17–22., Tampere.

Kapp, K. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruc-

tion. Pfeiffer, San Francisco, CA.

Koivisto, J. and Hamari, J. (2014). Demographic differ-

ences in perceived benefits from gamification. Com-

puters in Human Behavior 35, pages pp. 179–188.

Kuo, M. and Chuang, T. (2016). How gamification moti-

vates visits and engagement for online academic dis-

semination: An empirical study. Computers in Human

Behavior 55, pages pp. 16–27.

Park, H. and Bae, J. (2014). Study and research of gamifi-

cation design. Int. J. Softw. Eng. Appl.

Prasetiantowibowo, L. S. N. and Lusi-Ani, C. E. (2017). Im-

plementation of gamification to improve blood donors

by peer motivation application.

Simoes, J., Redondo, R., and Vilas, A. (2013). A social

gamification framework for a k-6 learning platform.

Computers in Human Behavior 29(2), pages pp.345–

353.

Vesa, M. e. a. (2017). Computer games and organiza-

tion studies. Organization Studies 38(2), page pp.

273–284.

Wilcoxon, F. (1945). Individual comparisons by ranking

methods. Biometrics Bulletin 1 (6), page pp. 80–83.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

244