Adult First-time User of Handheld Computer System: Challenges

Guy Toko

1

, Ernest Mnkandla

2

and Babajide Adewumi

1

1

College of Business and Economics, School of Consumer Intelligence and Information Systems,

Department of Applied Information Systems, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

2

Department of Computer Science, School of Computing, University of South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Keywords: Handheld Computer System, Adult, First-time User, Challenges.

Abstract: Handheld computing systems or devices can be defined as exceptionally portable, independent information

management and communication devices. Furthermore, handheld computing systems or devices can be seen

as a small or pocket-sized computing device with a touch screen keyboard and input and output interface.

According to the definition of handheld computing systems, numerous devices fit the description such as

smartphones, personal digital assistants (PDAs) and pagers. However, adult first- time users of computer

systems face different issues in adopting the device and the literature reviewed shows that most of them have

difficulties with the design, such as the touch screen. The negative views of technology devices by adult first-

time users can be attributed to the difficulty in adapting to new technology. Weakness, incapacity, distrust of

technology, absence of perceived value and trouble in understanding how to utilise the device are largely the

main problems observed by adult first-time users of handheld computer systems. However, they could accept

the use of the devices provided their needs are taken into consideration by the developers. The limitation of

the research was that only adults in the age range of 55 to 91 in Gauteng in South Africa were chosen for this

research.

1 INTRODUCTION

The introduction and use of technology (handheld

computer systems) in our daily activities have become

significant, regardless of the type of technology used.

At first, computer system evolution was limited to

computer experts.

Computers have now become working instruments

accessible to whoever can obtain and utilise them,

regardless of economic wellbeing, ability,

topographical area, education or training level and

sexual orientation (Toko, 2017). Older adults are now

broadly known to be a particularly diverse group who

do not regularly adapt to technology. However, there

has been a survey that shows that fears and concerns

linked to using computers, as well as opinions of skills

and capabilities in both utilising and learning to use

them, is lower or minimal compared to other age

groups (Marquié, et al., 2002). The use of technology

by adult individuals frequently relies on the

availability of training, and there is also the valid

question of whether it will provide precise value to

them.

The younger generation has an understanding and

knowledge of computers because they were often

taught how to use them at school or work, but this does

not necessarily apply to older adults, particularly those

whose jobs did not require the use of computers

(Barnard, et al., 2013).

Handheld computers can help connect the

computerised separation in this swiftly elderly world.

Older people did not experience the use of computers

in their childhoods, and a significant number of them

have never had computers. However, handheld

computing systems can expose older adults to better

and newer opportunities in the world of technology.

In creating or designing handheld computing

systems for adult first-time users, ease of use is one of

the problems they face (Kang & Yoon, 2008).

Usability challenges with input devices, list of options

and tasks, and output devices are hassled. Many of

these usability difficulties can be minimised with the

help of new technological innovations.

No matter how proactive, meticulous and efficient

the interactive design team of any electronic gadget,

household appliance or computing system is, it is not

always possible to predict human behaviour at the

time of development, and it is also difficult to predict

social aspects pertaining to the conditions the end-

users will be exposed to (Toko, 2017).

216

Toko, G., Mnkandla, E. and Adewumi, B.

Adult First-time User of Handheld Computer System: Challenges.

DOI: 10.5220/0009320202160227

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2020) - Volume 2, pages 216-227

ISBN: 978-989-758-417-6

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

This research was undertaken to assess adult first-

time users of handheld computing systems and to

evaluate the types of challenges they face when it

comes to adopting a computing system.

For this study, three research questions were

generated to make an assessment of adult first-time

users of handheld computers and investigate the

crucial issues faced by them in adopting the devices.

2 LITTERATURE REVIEW

Handheld computing systems or devices can be

defined as portable, independent information

management and communication devices (Weiss,

2003). Furthermore, they can be described as a small,

or pocket-sized, computing device with a touch screen

keyboard and input and output interface. According to

the definition of a handheld computing system,

numerous devices can fit the description, such as

smartphones, personal digital assistants (PDAs) and

pagers.

In addition, the device should be able to function

without cables, apart from recharging and

synchronising with a desktop computer. It must be

easy to use with one hand and not require a table for

support; it should also allow internet connectivity and

application support such as wireless application

protocol (WAP) or email (Weiss, 2003).

2.1 Understanding the Importance of

Computing Systems

The continuous inventive nature of computing

systems brands them perfect tools to influence society

in general. Computing systems have influenced our

daily lives, from the way we sleep and wake, the way

we talk to each other and everything else involved in

daily human activity (Reiss, 2012). Current evidence

suggests that more older adults are becoming aware of

the move to computerisation and that they are

becoming mindful of the advantages of using

computing systems (Morrel, et al., 2000). For

instance, adults, in general, can now use automatic

teller machines (ATMs) to withdraw money rather

than going to the bank and also to use popular

transportation applications (apps) to request transport.

Another study suggests that utilising computing

systems with internet access gives older adults a sense

of freedom and control over their day-to-day activities

(Morris, et al., 2007). Older adults with disabilities or

partial mobility can utilise digital technology or

handheld computing systems to maintain their social

networks and assist in their well-being (Choi &

DiNitto, 2013). Computing systems with internet

access offer new methods of communication for all

individuals as well as assisting older adults to

overcome hurdles in social interaction among

themselves (Young & Lo, 2012).

More computing systems awareness can enable

older adults to remain independent and maintain their

informal communities by emailing, instant messaging

or online chatting, as well helping them to be more

knowledgeable about their health issues and upgrade

their insight into medical problems (Karavidas, et al.,

2005).

2.2 Types of Handheld Computing

Systems

Handheld computing systems are not limited to

tablets, and there are numerous sizes and shapes

available in the market with different ways of utilising

them (Becta, 2003).

Handheld computing systems or devices can be

broken down into three different classifications, being

mobile phones, pagers and personal digital assistants

(PDAs) (Weiss, 2003).

Mobile phones or smartphones: These can be

described as devices or telephones that are

fundamentally for voice calls with an optional

use for short message services (SMSs) and

wireless application protocol (WAP) or I-mode,

two protocols for the mobile Internet. With the

expansion in the availability of mobile

information and communication technologies,

mobile phones have become the most well-

known specialised gadgets to interconnect

individuals (Kleinberger, et al., 2007). With the

noteworthy advance in technological

development, mobile phones have become the

biggest selling items in current society and give

a new shape to our lifestyles (Ventä, et al., 2008).

Pagers are handheld gadgets used primarily for

two-way email correspondence, but also include

some PDA capabilities, for example, contact

management and a schedule. A few pagers offer

Internet browsing. Pagers have QWERTY

keypads appropriate for 'two-thumb' typing.

QWERTY keypads are a variation appropriate

for handheld gadgets. The distinctive feature in

pagers and PDAs is the touch screen, which plays

an important part in the way in which

applications are designed and planned (Weiss,

2003).

PDAs are component-rich independent gadgets

that have address books and timetable schedule

Adult First-time User of Handheld Computer System: Challenges

217

capacities. A PDA has been defined as a

handheld computing system that has various

components, for example, address books, day

plans and logbooks that can serve as aids to

memory (Mayhorn, et al., 2005).

2.3 Addressing Handheld Computing

Adoption

A few scientists have shown that people are growing

up progressively more acquainted with innovation and

technology (Matlabi, et al., 2012). Nevertheless,

adults usually have substantially diverse desires,

concerns, capacities and capabilities when it comes to

technology, compared to younger people (Chen &

Persson, 2002). Consequently, understanding the

innovation or technology such as handheld computing

device adoption conduct of adult is significant.

The adoption of technology by adults is influenced

in two ways: direct positive influence and direct

negative influence (Melenhorst, et al., 2006). Direct

positive influence is related to advantages and lack of

expense. In particular, a benefit can be described as

the merit of using technological products, and lack of

costs can be described as the demerits that are

eliminated by using technological products. On the

other hand, direct negative influence is related to

expense and lack of advantages. Here, expenses refer

to the demerits of technological product usability and

lack of merits refers to the benefits of reducing

technological products usability (Melenhorst, et al.,

2006). However, irrespective of whether the

experience with technology is negative or positive, it

is the apparent advantages of technological products

or devices that most matter to adults in accepting

technologies.

Also, help from relatives and non-family

members, social and cultural variables, identity

attributes, communication media conduct and

socioeconomic status have all been identified as

assisting adults in the adoption of technologies such as

handheld computing systems (Quan-Haase, et al.,

2016).

2.4 Discovering Handheld User

Challenges

Due to age-related, physiological weakening and

mental and social-ecological changes, it is difficult for

adult first-time users to adjust to new technology such

as handheld computing systems and a large number of

them dismiss the new devices quickly (Lee, et al.,

2014).

The negative view of technology devices by adult

first-time users can also be attributed to the acceptance

of technology. Weakness, incapacity, distrust of

technology, absence of perceived value and difficulty

in working out how to use the device are the main

problems encountered by adult first-time users in

endeavouring to accept new technologies such as

handheld devices (Czaja & Sharit, 2016).

Recently, five issues that adult first-time users face

have been identified, accessibility, right to use, way of

life, physical impediments and confidentiality (Yuan,

et al., 2016). There are a few physiological capabilities

that are basic requirements for the use of technology

devices, for example, vision, hearing and memory, all

of which decline with age (Schewe, 1998). Adults in

general slowly lose fundamental physical capabilities

which change their perspectives about technology

such as handheld computing systems (Buckner, 2004).

3 RESEARCH QUESTION

What is the importance of handheld computing

systems in adulthood? What are some of the

challenges when it comes to adopting handheld

computing systems? What are the best mechanisms to

have when it comes to adopting handheld systems?

What is a Handheld Computing System?

4 METHODOLOGY

Methodology is an understandable set of approaches

that complement each other and also have the

capability to deliver suitable data and results that will

answer the research question as well as uniform

research purpose (Castro, et al., 2010). Research

methodology can be portrayed as the methodical,

hypothetical examination of methods associated with

a field of study. A methodology does not set out to

provide answers. It is not the same thing as a method

but offers hypothetical support for understanding

which set of methods, or best practices can be used for

particular research (Ishak & Alias, 2005).

In addition, methodology is a framework of

theories and principles based on the methods and

procedures used. Research methodology can be

grouped into two aspects which are quantitative and

qualitative research methodologies (Bryman, 2012).

A quantitative method was used for this study,

based on the empirical investigation of social

incidence with the help of statistical, mathematical or

numerical data techniques (Kaplan, 2004). A

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

218

descriptive research design was also used as it

explains the incidence of a variable, the connection

between different variables and also assists in deciding

when and how many observations or interviews to use

in assessing the challenges faced by adult first-time

users of handheld computing systems. In addition, a

survey was included because it is a non-experimental

strategy which was used to evaluate parameters such

as age, sex, conjugal status, conduct, assessments and

emotions for a particular subject (Shaughnessy, et al.,

2011).

4.1 Data Collection Techniques

Data collection can be defined as the orderly

assembling or gathering of data from numerous

sources for a particular reason and can include

questionnaires, interviews, observations or records

that already exist. Quantitative or qualitative

techniques can be used for collecting data (KPMG,

2010). In this case, a quantitative technique was used

to collect data with the help of a well-structured

questionnaire.

A questionnaire can be described as a cluster or

sequence of questions aimed at producing data from a

source or respondent when administered an

interviewer or by filling in the questionnaire.

Questionnaires can be categorised into three types,

namely unstructured, semi-structured and structured

(Guo, 2015).

4.2 Research Population

A research population is the number of items, subjects

or members that conform to a set of specifications

(Yogesh, 2006). The research population is the entire

group of a well-defined class of individuals, items,

places or proceedings identified as a result of the

research question (Hawe & Potvin, 2009). A

population is also said to be an accumulation of all the

objects, subjects or members that obey a set of plans.

A target population refers to a set of individuals,

objects, or features that might add important and

constructive documentations of the kind of effort they

may give (Marczyk, et al., 2005). Hence, the targeted

population for this research was adults in Gauteng

province, South Africa, who were first-time users of

handheld computing systems or those who had never

used any form of ICT device except a cellular

telephone.

4.3 Research Sampling

Sampling can be described as the process whereby

individuals are selected from the population in such a

way that each individual has an equal opportunity to

be chosen (Yogesh, 2006). A sample is a portion of

the population selected for particular research. It is a

subset of a population, and the technique for selecting

the sample might be centred on probability and non-

probability.

Probability sampling, individual partaker of the

population has a known non-zero probability of being

chosen. The probability technique consists of random,

systematic and stratified sampling. In non-probability

sampling, participants are assigned from the

population in a non-random manner. The non-

probability technique comprises convenience,

judgement, quota and snowball sampling.

Probability sampling was selected for this study

because sampling errors can be calculated and

eliminated. A sampling error is the degree to which a

sample might vary from the general population

(Marczyk, et al., 2005).

4.4 Research Sample Size

The bigger the sample, the more representative it will

be, smaller samples give less reliable results as they

are probably going to be less representative of the

population (Depoy & Gitlin, 2005). The decision

about sample size is not a direct one; it relies on

various considerations and does not have a conclusive

answer.

In this research, 50 questionnaires were distributed

to the targeted population, and 27 of the participants

responded about the challenges being faced by them

as first-time adult users of handheld computing

systems or devices.

4.5 Data Collection Procedures

The literature reviewed stated that adult first-time

users of handheld computing systems face some

challenges in using them. We met with various

participants of the research population and

administered structured questionnaires that contained

open-ended questions. The survey questionnaires

allowed participants to answer questions centred on

individual involvement with handheld computing

systems and the challenges they faced. The structured

questionnaire consisted of the following attributes and

was the instrument used to measure the integrity of the

data collected.

Adult First-time User of Handheld Computer System: Challenges

219

Validity can be referred to as the level of truth or

erroneousness of the data collected with the help of the

research instrument. It can also be characterised as

both the external and internal validity of the measuring

instrument (Graeme, et al., 2006). Validity states the

level of truth or erroneousness of the predicted

challenges adult first-time users of handheld

computing systems experienced while using it.

Reliability states the regularity of amount of a

concept (Singer, 2003). Reliability can be considered

as the measure of normality with which the instrument

estimates a characteristic (Shaughnessy, et al., 2011).

It can also be referred to as the sum to which

autonomous direction of a similar instrument delivers

similar results under proportionate conditions (Thyer,

2001). The less variety the instrument yields in

repetitive estimations of an element, the higher the

reliability. There is comparability connection among

reliability as well as validity. An instrument that is not

valid can never be reliable in research. Data Analysis

and Discussions

Data analysis is the procedure of getting raw data

and translating it into valuable information for

decision making by users or researchers. Data are

gathered as well as investigated to respond to

questions, test hypotheses or negate theories (Judd, et

al., 2011).

Tukey et al (1962) characterised data analysis as

the methodology for investigating data, techniques for

deciphering the outcome of such procedures, methods

for arranging the collection of data to make its

investigation simpler, more detailed or more exact and

all the apparatus and after-effects of (scientific) which

apply to analysing data [40].

Data analysis is the procedure of methodically

applying arithmetical and coherent systems to explain

and demonstrate, summarise, recap and assess data

(Shamoo & Resnik, 2003).

4.6 Data Analysis Techniques and

Procedures

Data analysis techniques allow research analysts to re-

evaluate assembled data and develop surmising or

reason from the data. There are different types of data

analysis, including quantitative and qualitative

analysis. Quantitative data analysis can be referred to

as the process of quantifying

5 RESULTS ANALYSIS

Collected data either numerically or arithmetically,

while qualitative data analysis is non-numeric or non-

arithmetic, its method is principally steered by the

actual material at hand.

Quantitative data analysis was used in this study

and can be categorised into various aspects which

include descriptive statistics, exploratory data

analysis, confirmatory data analysis and correlation

and regression data analysis. In this research,

descriptive data analysis was used to analyse the

collected data. Descriptive data analyses are used to

portray the fundamental highlights of the data in an

investigation or a research project and they offer basic

summaries about the sample and the measures

(Trochim, 2006). Descriptive data analyses are used to

present quantitative explanations in a convenient

structure. Descriptive data analysis also helps us to

condense huge amounts of data in a reasonable way

with simple graphics analysis.

There are numerous methods and software

packages available for data analysis. The appropriate

and most ideal procedure for data analysis is to collect

the data and check for validity and reliability before

entering it into Excel or any other data analysis

software. The procedure of data analysis also checked

for the variables of the analysed data before displaying

it, and a likely scale of point ranging from strongly no

to strongly yes was used in the research data analysis.

5.1 Demography

Demography can be referred to as the study of a

particular population for research based on things such

as age, race and sex, although, other areas can also be

involved in the demographics of research.

The demography for this research was based on

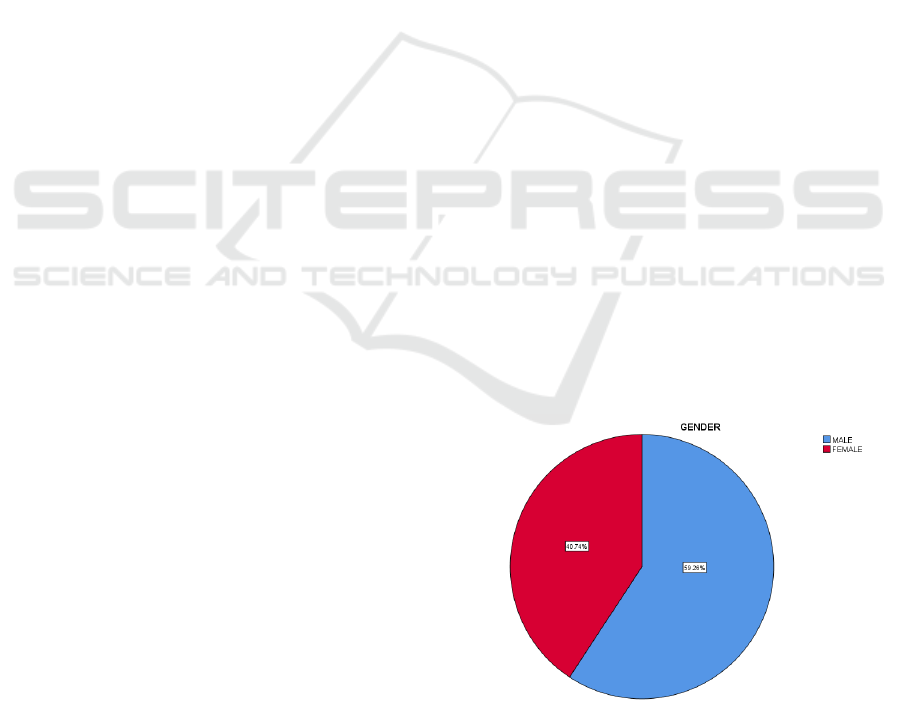

sex or gender, age and ethnicity. Below is a pie chart

depicting this.

Figure 1: Gender.

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

220

Table 1: Gender.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid Male 16 59.3 59.3 59.3

Female 11 40.7 40.7 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

The analysis of gender data collection indicated that

male respondents were in the majority, being 59.2%

compared to the female respondents at 40.74%.

Table 2: Age.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid 55-70 19 70.4 70.4 70.4

71-91 8 29.6 29.6 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

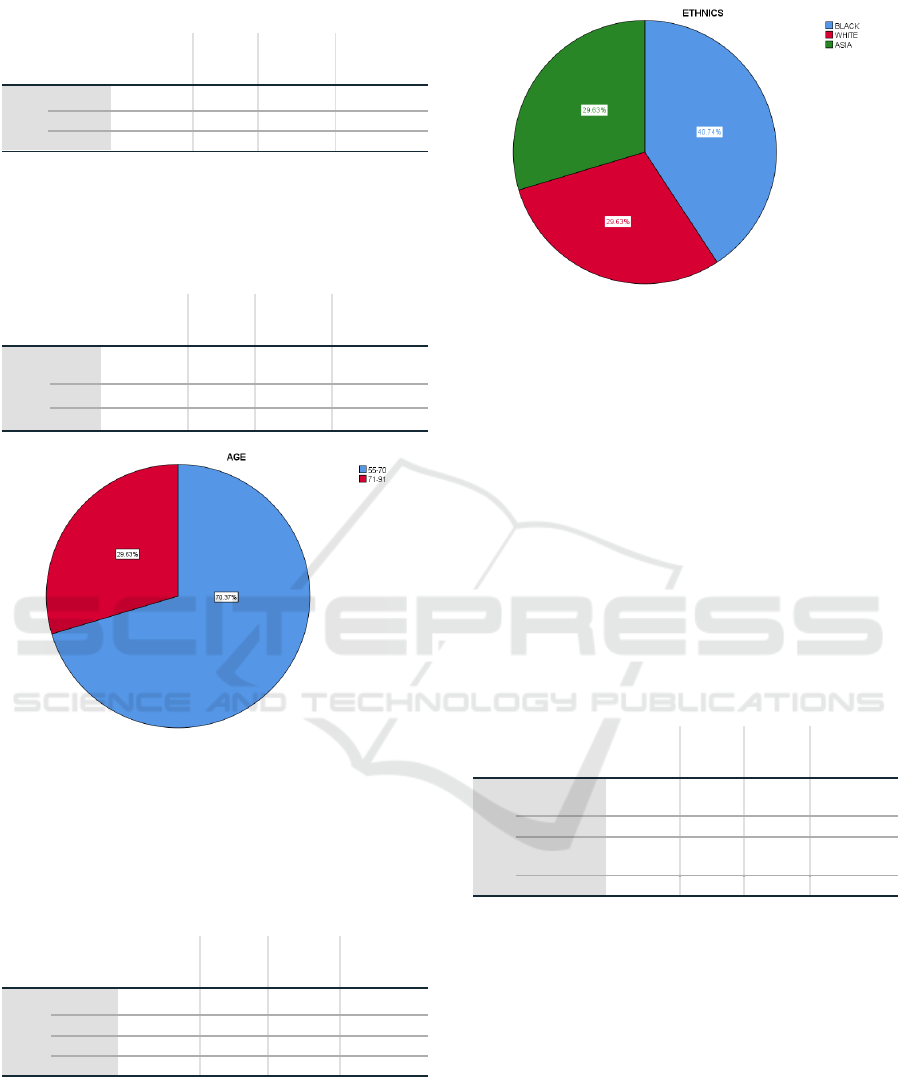

Figure 2: Age.

Adults were divided into two age groups, 55-70

and 71-91. There were 19 respondents in the age group

55-70 (70.37%), and 8 respondents in the 71-91 age

group (29.63%).

Table 3: Ethnicity.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid BLACK 11 40.7 40.7 40.7

WHITE 8 29.6 29.6 70.4

ASIAN 8 29.6 29.6 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Figure 3: Ethnicity.

The majority of adults who participated in this

research were black (40.74%), 29.63% were white,

and the remaining 29.63% were Asian. This analysis

allows us to know how many adults in each ethnic

group participated.

5.2 Answering the Research Questions

from the Collected Data

a) What is the importance of handheld

computing systems in adults: The findings from the

data analysis of the first research question which

involved the importance of handheld computing

systems in adults, are shown in the Tables below.

Table 4: Question 1.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid SLIGHTLY

YES

5 18.5 18.5 18.5

YES 11 40.7 40.7 59.3

STRONGL

Y YES

11 40.7 40.7 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 1: Have you ever accessed the Internet? The

majority of the respondents answered Yes meaning

100% of them have accessed the Internet by means of

handheld computing or other systems. However,

according to the literature reviewed, computing

systems with Internet access offer new methods of

communication which are available to all individuals

as well as to assist older adults in overcoming hurdles

in social interaction among themselves (Young & Lo,

2012).

Adult First-time User of Handheld Computer System: Challenges

221

Table 5: Question 2.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid NO 5 18.5 18.5 18.5

NEUTRAL 2 7.4 7.4 25.9

SLIGHTLY

YES

8 29.6 29.6 55.6

YES 8 29.6 29.6 85.2

STRONGLY

YES

4 14.8 14.8 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 2: Have you ever used a handheld computing

system? Data analysis showed that a few respondents

(7.4%) answered ‘Neutral’ to this question; 18.5% of

them answered ‘No’ and 74% answered ‘Yes’. With

regard to this finding, a few scientists have shown that

adults are growing up progressively more acquainted

with innovation or technology (Matlabi, et al., 2012).

Nevertheless, adults usually have substantially more

diverse needs, concerns, capacities and capabilities

with technology or innovation compared to younger

people (Chen & Persson, 2002).

Table 6: Question 4.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid STRONGLY

NO

2 7.4 7.4 7.4

SLIGHTLY

NO

2 7.4 7.4 14.8

NO 6 22.2 22.2 37.0

NEUTRAL 9 33.3 33.3 70.4

SLIGHTLY

YES

8 29.6 29.6 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 4: Is a handheld computing system useful for

your daily tasks? Elements of effectiveness, efficiency

and fulfilment ought to be considered as discrete and

autonomous parts of understanding the usability of

handheld computing systems (Frøkjær, et al., 2000).

According to the data analysis, 33.3% of the

respondents answered ‘Neutral’, 37% answered ‘No’,

and 29.6% answered ‘Yes’ to this question. However,

the latest information demonstrates that older adults

utilise different types of technology such as automated

teller machines (ATMs) compared to the younger ones

(Czaja, et al., 2006). In addition, older adults are left

behind and are less independent if they do not have

access to and are not able to utilise technology. For

instance, handheld computing systems with Internet

access are quickly turning into a significant means of

communicating and distributing information about

wellbeing, society and government services.

Table 7: Question 5.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid STRONGLY

NO

2 7.4 7.4 7.4

SLIGHTLY

NO

2 7.4 7.4 14.8

NO 8 29.6 29.6 44.4

NEUTRAL 10 37.0 37.0 81.5

SLIGHTLY

YES

5 18.5 18.5 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 5: Does the handheld computing system

interface suit your lifestyle? Based on the outcome of

this particular question, the respondents said the

interface of handheld computing systems does not suit

them; 44.4% said ‘No’, 18.5% said ‘Yes’ and 37%

were ‘Neutral’. The result also showed that not much

has been done to make the handheld computing

system interface suitable to adult first-time users.

Technology may have some adverse impacts on well-

being, and it is vital to ensure that the introduction of

technology into the lives of older adults is done

analytically and with care to suit their lifestyles

(Dickinson & Gregor, 2006).

Table 8: Question 14.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid STRONGLY

NO

2 7.4 7.4 7.4

SLIGHTLY

NO

4 14.8 14.8 22.2

NEUTRAL 13 48.1 48.1 70.4

SLIGHTLY

YES

8 29.6 29.6 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 14: Will you use handheld computing

systems? The findings from this question indicated

that the majority of the respondents said they did not

know if they would use a handheld computing system,

48.1% were ‘Neutral’, 22.2% said ‘No’, and 29.6%

said ‘Yes’. The usability of handheld computing

systems has been explored for some time. Scientists

place emphasis on improving ease of use by

considering the impact of age-related physical

deterioration (Zhou, et al., 2012). The basic reason

that adults do not accept handheld computing systems

is, by all accounts, as a result of having difficulty in

using them. This means that, if ease of use improves,

they would more readily accept handheld computing

systems.

b) What are some of the challenges when it

comes to adopting handheld computing systems: The

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

222

data collected from the respondent's answers to this

question were analysed and discussed in the Tables

below.

Table 9: Question 6.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid SLIGHTLY

NO

1 3.7 3.7 3.7

NO 1 3.7 3.7 7.4

NEUTRAL 7 25.9 25.9 33.3

SLIGHTLY

YES

9 33.3 33.3 66.7

YES 2 7.4 7.4 74.1

STRONGLY

YES

7 25.9 25.9 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 6: Do you have issues using a handheld

computing touch screen? Based on the feedback from

the respondents, 25.9% were ‘Neutral’, 7.4% said

‘No’ and 66.6% said ‘Yes’. Meaning they are having

issues using handheld computing system touch

screens. The literature reviewed of handheld

computing systems emphasises that adults, in general,

slowly lose fundamental physical capabilities which

makes their perspectives about technology such as

handheld computing systems change (Buckner, 2004).

Table 10: Question 7.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid STRONGLY

NO

1 3.7 3.7 3.7

SLIGHTLY

NO

6 22.2 22.2 25.9

NEUTRAL 3 11.1 11.1 37.0

SLIGHTLY

YES

8 29.6 29.6 66.7

YES 9 33.3 33.3 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 7: Can you see the display input on handheld

computing system? The respondents have different

views on this question. When it comes to seeing the

display, 11.1% of the respondents said they were

‘Neutral’, 25.9% said ‘No’, they cannot see the display

input and 62.9% said ‘Yes’ they can see it.

Table 11: Question 8.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid STRONGLY

NO

1 3.7 3.7 3.7

SLIGHTLY

NO

3 11.1 11.1 14.8

NO 3 11.1 11.1 25.9

NEUTRAL 10 37.0 37.0 63.0

SLIGHTLY

YES

9 33.3 33.3 96.3

YES 1 3.7 3.7 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 8: Can you navigate through handheld

computing system functions easily? The negative

views of adult first-time users can be attributed to

hurdles in accepting technology. The outcome of this

analysis indicated that 37.0% of them chose ‘Neutral’,

25.9% said ‘No’, and 37% said ‘Yes’. Weakness,

incapacity, distrust of technology, absence of

perceived value and trouble working out how to utilise

the device are the main challenges observed by adult

first-time users in endeavouring to accept new

technologies such as handheld devices (Czaja &

Sharit, 2016).

Table 12: Question 9.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid NEUTRAL 2 7.4 7.4 7.4

SLIGHTLY

YES

8 29.6 29.6 37.0

YES 14 51.9 51.9 88.9

STRONGLY

YES

3 11.1 11.1 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 9: Do you struggle to select a specific icon

because your thumb feels too big for the device? The

data analysis for this research question shows that

7.4% of the respondents chose ‘Neutral’, 92.6% and

chose ‘Yes’ meaning they are struggling to select a

specific icon on the device. Based on the review of the

literature, adults are sluggish in movement and make

more sub-movements in operating handheld

computing systems (Hertzum & Hornbæk, 2010).

This impacts content entry and pointing activities.

Adult First-time User of Handheld Computer System: Challenges

223

Table 13: Question 10.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid NO 1 3.7 3.7 3.7

NEUTRAL 10 37.0 37.0 40.7

SLIGHTLY

YES

5 18.5 18.5 59.3

YES 5 18.5 18.5 77.8

STRONGLY

YES

6 22.2 22.2 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 10: Do you feel that you have to remember

too many functions while using handheld computing

systems? Adult first-time users of handheld

computing systems felt that they have to remember too

many functions while using the device; 59.2% of them

said ‘Yes’, 37.0% were ‘Neutral’ and 3.7% said ‘No’.

On account of age-related, physiological weakening,

just as mental and social-ecological changes, it is

troublesome for adult first-time users to adjust to new

technology devices such as handheld computing

systems, and a large number of them quickly dismiss

new devices (Lee, et al., 2014).

c) What are the best mechanisms to have when

it comes to adopting handheld systems: Data

collected from the responses to this question were

analysed is discussed below for each of the questions.

Table 14: Question 3.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid NEUTRAL 6 22.2 22.2 22.2

SLIGHTLY

YES

5 18.5 18.5 40.7

YES 9 33.3 33.3 74.1

STRONGLY

YES

7 25.9 25.9 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 3: Can you afford any kind of handheld

computing system? The majority of the respondents

(77.7%) said ‘Yes’ and 22.2% chose ‘Neutral’. The

adoption of technology, such as a handheld computing

system, is influenced by two types of influence: direct

positive influence and direct negative influence

(Melenhorst, et al., 2006). Direct positive influence is

related to advantages, and lack of expense and direct

negative influence is related to expenses and lack of

advantages.

Table 15: Question 11.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid SLIGHTLY

NO

1 3.7 3.7 3.7

NO 3 11.1 11.1 14.8

NEUTRAL 8 29.6 29.6 44.4

SLIGHTLY

YES

11 40.7 40.7 85.2

YES 4 14.8 14.8 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 11: Did your previous experience as a

mobile device user help in accepting a handheld

computing system as a tool? The majority of

respondents (55.5%) answered ‘Yes’ to this question;

29.6% were neutral, and 14.8% said ‘No’.

Table 16: Question 12.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid NO 2 7.4 7.4 7.4

NEUTRAL 5 18.5 18.5 25.9

SLIGHTLY

YES

11 40.7 40.7 66.7

YES 7 25.9 25.9 92.6

STRONGLY

YES

2 7.4 7.4 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 12: Do you ask for help when using a

handheld computing system? The majority of the

respondents (74%) answered ‘Yes’, 7.4% said ‘No’

and 18.5% chose to be neutral. With regard to the

literature reviewed, help from relatives and non-

family members, social and cultural variables, identity

attributes, communication media conduct and

socioeconomic status have all been identified as

assisting adults in the adoption of technologies such as

handheld computing systems (Quan-Haase, et al.,

2016).

Table 17: Question 13.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid SLIGHTLY

NO

1 3.7 3.7 3.7

NEUTRAL 14 51.9 51.9 55.6

SLIGHTLY

YES

1 3.7 3.7 59.3

YES 4 14.8 14.8 74.1

STRONGLY

YES

7 25.9 25.9 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 13: Is a handheld computing system too

smart or fast for your liking? The data collected and

analysed from this question showed that 44.4% of the

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

224

respondents said ‘Yes’ that a handheld device is too

smart for them, 51.9% were neutral, and 3.7% said

‘No’ to the question.

Table 18: Question 15.

Frequency Percent

Valid

Percent

Cumulative

Percent

Valid STRONGLY

NO

12 44.4 44.4 44.4

SLIGHTLY

NO

5 18.5 18.5 63.0

NO 7 25.9 25.9 88.9

NEUTRAL 3 11.1 11.1 100.0

Total 27 100.0 100.0

Question 15: Do you feel that your needs as an adult

first-time user were taken into consideration by

systems developers? This particular question was

designed for the developers to know what is needed in

developing handheld computing systems that will be

user-friendly for adult first-time users of handheld

devices. However, with the data collected and

analysed, 88.8% of respondents said ‘No’ to this

question, and 11.1% chose to be neutral.

6 CONCLUSION

The main aim of this research study was to gain an

understanding and knowledge of challenges being

faced by adult first-time users of handheld computing

systems. To provide solutions to these issues, a

literature review was carried out to find out the extent

of the challenges.

A few of the challenges faced by adult first-time

users of handheld computing systems can be described

as usability and acceptability of computing systems in

general. Adult first-time users have issues with the

design interface of handheld computing systems such

as screen displays and hieratical menus.

A broad literature review was done to gain full

knowledge and understanding of the importance of

computing systems in general. Computing systems

have changed our lifestyles in the way we live and do

things. They also allow us access to information when

required. Handheld computing systems can assist

adults, in particular, to overcome social exclusion,

keep contact and enable them to have free access to

information such as health and society information.

We also explored different kinds of handheld devices

and the value they add to the life of adult first-time

users.

A structured questionnaire and suitable population

sampling were used to gather data from the research

population. Probability sampling was considered to be

the best method of sampling to avoid sampling errors.

Validity and reliability were instruments used in

validating collected data and measuring the integrity

of data collected from the participants.

The research sample size was 50 adults between

the ages of 55 and 91 in Gauteng province, South

Africa and was not randomised. The outcome of the

research is only relevant to this sample and cannot be

generalised.

A large percentage of the data and information

originated from the point of view of the research

participants. The participants should not have had any

motivation to incorporate feelings in their answers, but

this does not guarantee the precision of the responses.

The participants may not be completely mindful of

their conduct or discard data that they have just

overlooked

The restricted time to accumulate information and

data from research participants impacted how much of

it could be assembled. The number, as well as the

nature of the questions in the research questionnaire,

needed to be completed within a short time, which

meant the scope of the questions was limited.

Lastly, adoption and usability of handheld devices

by adult first-time users can be seen as a big issue.

However, a proper design interface such as

considering age-related issues like a decline in vision,

hearing and movement should be considered for adult

users in general when any technology interface is

developed.

REFERENCES

Barnard, Y., Bradley , M. D., Hodgson, F. & Lloyd, A. D.,

2013. Learning to use new technologies by older adults:

Perceived difficulties, experimentation behaviour and

usability. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), pp.

1715-1724.

Becta, 2003. webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. [Online]

Available at: http://foi.becta.org.uk/content_files/

corporate/resources/technology_and_education_resear

ch/handheld_computers. [Accessed 18 April 2019].

Bryman, A., 2012. Social research methods. 4th ed. New

York: Oxford press.

Buckner, R. L., 2004. Memory and executive function in

aging and AD: multiple factors that cause decline and

reserve factors that compensate. Neuron, 44(1), pp.

195-208.

Castro, F. G., Kellison, J. G., Boyd, S. J. & Kopa, A., 2010.

A methodology for conducting integrative mixed

methods research and data analyses. Journal of mixed

methods research, 4(4), pp. 342-360.

Adult First-time User of Handheld Computer System: Challenges

225

Chen, Y. & Persson, A., 2002. Internet use among young

and older adults: Relation to psychological well-being.

Educational Gerontology, 28(9), pp. 731-744.

Choi, N. G. & DiNitto, D. M., 2013. The digital divide

among low-income homebound older adults: Internet

use patterns, eHealth literacy, and attitudes toward

computer/Internet use. Journal of medical Internet

research, 15(5), p. 93.

Czaja, S. J. et al., 2006. Factors predicting the use of

technology: findings from the Center for Research and

Education on Aging and Technology Enhancement

(CREATE). Psychology and aging, 21(2), p. 333.

Czaja, S. J. & Sharit, J., 2016. Designing training and

instructional programs for older adults. s.l.:CRC Press.

Depoy, E. & Gitlin, L. N., 2005. Introduction to Research:

Understanding and Applying Multiple Strategies. St.

Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Dickinson, A. & Gregor, P., 2006. Computer use has no

demonstrated impact on the well-being of older adults.

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies,

64(8), pp. 744-753.

Frøkjær, E., Hertzum, M. & Hornbæk, K., 2000. Measuring

usability: are effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction

really correlated?. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI

conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

pp. 345-352.

Graeme, H., Paulo, R. & Luiz, M., 2006. Advances in

Doctoral Research in Management (Vol. 1). s.l.:World

Scientific.

Guo, S., 2015. Shaping social work science: What should

quantitative researchers do?. Research on Social Work

Practice, 25(3), pp. 370-381.

Hawe, P. & Potvin, L., 2009. What is population health

intervention research?. Canadian journal of public

health, 100(1), pp. 18-114.

Hertzum, M. & Hornbæk, K., 2010. How age affects

pointing with mouse and touchpad: A comparison of

young, adult, and elderly users. Intl. Journal of Human–

Computer Interaction, 26(7), pp. 703-734.

Ishak, I. S. & Alias, R. A., 2005. Designing a strategic

information system planning methodology For

Malaysian institutes of higher learning (ISP-IPTA),

Malaysia: Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

Judd, C. M., McClelland, G. H. & Ryan, C. S., 2011. Data

analysis: A model comparison approach. 2nd ed. New

York: Routledge.

Kang, N. E. & Yoon, W. C., 2008. Age-and experience-

related user behavior differences in the use of

complicated electronic devices. International Journal

of Human-Computer Studies, 66(6), pp. 425-437.

Kaplan, D., 2004. The Sage handbook of quantitative

methodology for the social sciences. s.l.:Sage.

Karavidas, M., Lim, N. K. & Katsikas, S. L., 2005. The

effects of computers on older adult users. Computers in

human behavior, 21(5), pp. 697-711.

Kleinberger, T., Becker, M., Ras, E. & Holzinger, A., 2007.

Ambient intelligence in assisted living: enable elderly

people to handle future interfaces. International

conference on universal access in human-computer

interaction, pp. 103-112.

KPMG, 2010. From hype to future: KPMG’s 2010 Cloud

Computing survey. [Online] Available at: http://

www.techrepublic.com/whitepapers/from-hype-to-

future-kpmgs-2010-cloud-computing-survey

[Accessed 5 May 2019].

Lee, E., Han, S. & Chung, Y., 2014. Internet use of

consumers aged 40 and over: Factors that influence full

adoption. Social Behavior and Personality: an

international journal, 42(9), pp. 1563-1574.

Marczyk, G., DeMatteo, D. & Festinger, D., 2005.

Essentials of research design and methodology.

s.l.:John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Marquié, J. C., Jourdan-Boddaert, L. & Huet, N., 2002. Do

older adults underestimate their actual computer

knowledge?. Behaviour & Information Technology,

21(4), pp. 273-280.

Matlabi, H., Parker, S. G. & McKee, K., 2012. Experiences

of extra care housing residents aged fifty-five and over

with home-based technology. Social Behavior and

Personality: an international journal, 40(2), pp. 293-

300.

Mayhorn, C. B., Lanzolla, V. R., Wogalter, M. S. &

Watson, A. M., 2005. Personal digital assistants

(PDAs) as medication reminding tools: Exploring age

differences in usability. Gerontechnology, 4(3), pp.

128-140.

Melenhorst, A. S., Rogers, W. A. & Bouwhuis, D. G., 2006.

Older adults' motivated choice for technological

innovation: Evidence for benefit-driven selectivity.

Psychology and aging, 21(1), p. 190.

Morrel, R. W., Mayhorn, C. B. & Bennett, J., 2000. A

survey of World Wide Web use in middle-aged and

older adults. Human Factors, 42(2), pp. 175-182.

Morris, A., Goodman, J. & Brading, H., 2007. Internet use

and non-use: views of older users. Universal access in

the information society, 6(1), pp. 43-57.

Quan-Haase, A., Martin, K. & Schreurs, K., 2016.

Interviews with digital seniors: ICT use in the context

of everyday life. Information, Communication &

Society, 19(5), pp. 691-707.

Reiss, E., 2012. Usable usability: simple steps for making

stuff better. s.l.:John Wiley & Sons.

Schewe, C. D., 1998. Marketing to our aging population:

Responding to physiological changes. Journal of

Consumer Marketing, 5(3), pp. 61-73.

Shamoo, A. E. & Resnik, B. R., 2003. Responsible Conduct

of Research. s.l.:Oxford University Press.

Shaughnessy, J., Zechmeister, E. & Jeanne, Z., 2011.

Research methods in psychology. New York: McGraw

Hill.

Singer, E., 2003. Exploring the meaning of consent:

participation in research and beliefs about risks and

benefits. Journal of Official Statistics, 19(3), p. 273.

Thyer, B. A., 2001. The handbook of social work research

methods. s.l.:Sage.

Toko, G. R., 2017. Closing the digital gap: handheld

computing, adult first-time users, and a user experience

metric model,

Pretoria: Unisa.

Trochim, W. M., 2006. The Research Methods Knowledge

Base. [Online] Available at: http://

CSEDU 2020 - 12th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

226

www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/ [Accessed 21

August 2019].

Tukey, J. W., 1962. The future of data analysis. The annals

of mathematical statistics, 33(1), pp. 1-67.

Ventä, L., Isomursu, M., Ahtinen, A. & Ramiah, S., 2008.

“My phone is a part of my soul”–How People Bond

with Their Mobile Phones. The Second International

Conference on Mobile Ubiquitous Computing, Systems,

Services and Technologies, pp. 311-317.

Weiss, S., 2003. Handheld usability. s.l.:John Wiley &

Sons.

Yogesh, K. S., 2006. Fundamental Of Research

Methodology And Statistics. India: New Age

International.

Young, C. M. Y. & Lo, B. C. Y., 2012. Cognitive appraisal

mediating relationship between social anxiety and

internet communication in adolescents. Personality and

Individual Differences, 52(1), pp. 78-83.

Yuan, S., Hussain, S. A., Hales, K. D. & Cotten, S. R., 2016.

What do they like? Communication preferences and

patterns of older adults in the United States: The role of

technology. Educational Gerontology, 42(3), pp. 163-

174.

Zhou, J., Rau, P. L. P. & Salvendy, G., 2012. Use and

design of handheld computers for older adults: A

review and appraisal. International Journal of Human-

Computer Interaction, 28(12), pp. 799-826.

Adult First-time User of Handheld Computer System: Challenges

227