A Patient’s Perspective on Decision-making for the Adoption of

Digital Care Pathways

Raja Manzar Abbas

1

, Noel Carroll

1,2

and Ita Richardson

1,3

1

Lero - The Irish Software Research Centre, Ireland

2

Business Information Systems, NUI Galway, Galway, Ireland

3

ARC – Ageing Research Centre, HRI - Health Research Institute, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

Keywords: Patient-centred Care, Healthcare Information Systems, Digital Care Pathway, Decision-making, Adoption.

Abstract: Healthcare Information Systems (HIS) are implemented to provide high-quality, patient-centred care. Yet,

there is little evidence about the decision-making role patients play for the adoption of HIS nor what factors

patients deem essential in the adoption of HIS. To guide healthcare practitioners in decision-making for the

adoption of HIS, this study reports on the key factors which influence patients’ perception and use of HIS.

Specifically, a qualitative study was conducted with 15 patients to understand the phenomenon of patient

decision-making for the adoption of HIS. Our findings identify the concept of ‘Digital Care Pathways’ and

indicate that there are four primary decision factors which influence the adoption of HIS: (i) trust; (ii) fear;

(iii) ease of use; and (iv) accessibility. To synthesise the findings, we present the patients decision-making

framework for digital care pathways as a first step to encapsulate the patients’ perspective of decision-making

factors associated with adopting innovations for digital care pathways.

1 INTRODUCTION

Healthcare delivery systems throughout the world

have been made possible by the advancement of

Information System (IS). Increasing attention has

been given to implementing healthcare information

systems (HIS) in hospitals, particularly regarding the

need to consider the acceptance and usage of HIS

among healthcare professionals (Ismail et al., 2015).

We coin the phrase ‘Digital Care Pathways’ to

refer to online services provided by hospitals. Digital

Care Pathways can provide a digital solution to the

patients, and it may bring other benefits, such as

standardized care and greater control over the delivery

of care. HIS is one of the applications that can be used

to provide a digital solution for patients. By adopting

HIS applications, hospitals also gain significant

benefits, ranging from improved diagnosis, thereby

delivering better patient care and improved the

support of clinical decision-making. This enhances

hospital productivity, lowers costs, and reduces

medication errors (Aron et al., 2011). Technological

advancements made in medical science have offered

new choices which are upgrading outcomes of care,

yet it has inadvertently dissociated clinicians from the

patients. Therefore, a healthcare environment has

been established where, often, patients and their

families are not involved in their significant treatment

decisions and discussions. Patients can be left in

obscurity about how their issues are being handled

and further on how to direct the profound range of

diagnostic choices accessible to them (Epstein et al.,

2011).

1.1 Patient-centred Care

The term, “patient-centred care”, was introduced by

the Picker/Commonwealth Program for Patient-

Centred Care (now the Picker Institute) to present the

significance of having a better understanding by

clinicians of the patient and family experience of

illness. Additionally, patient-centred care should

support patients’ needs during their time in a very

difficult and often complex care delivery system

(Barry and Edgman-Levitan, 2012). Over the past few

decades, renewed focus had emerged around patient-

centred care as an attempt to avert the trend away from

focusing on diseases and reverting back to the

patient’s needs and satisfaction (Gerteis et al., 1993).

The most significant characteristic of patient-

centred care is the dynamic commitment of patients

when healthcare choices must be made — moreover,

Abbas, R., Carroll, N. and Richardson, I.

A Patient’s Perspective on Decision-making for the Adoption of Digital Care Pathways.

DOI: 10.5220/0008967704470454

In Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2020) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 447-454

ISBN: 978-989-758-398-8; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

447

when an individual patient lands at an intersection of

medicinal possibilities, diverging pathways have

extraordinary and significant results with lasting

ramifications. These include, for instance, decision-

making in major surgeries, prescriptions to be taken for

the rest of a patient’s life, and screening and

symptomatic tests that can trigger upsetting

interventions. The procedure by which the optimal

decision might be reached regarding a patient is termed

as shared decision-making. It includes, at least, a

clinician and the patient, while other members from the

medical team or households might be allowed to

participate. Every member is in this way outfitted with

a better comprehension of the pertinent factors and

wisely shares responsibility in the choice about how to

pursue treatment (Delbanco and Gerteis, 2012).

The adoption of HIS is similarly an essential

decision in a hospital, and central to this is the

decision-making process. However, despite an

accumulation of best practices, frameworks and

research which has identified success factors, the

function of hospital decision-makers, especially

patients, in the adoption process of new technologies

remains unreported (Yang et al., 2013).

1.2 Problem Statement

The objective of this paper is to report on an empirical

study conducted with patients on the role they play in

decision-making for the adoption of HIS. We look

particularly at the assumptions around ‘patient-

centric’ technology and the role of patients in

decision-making.

There is an apparent lack of insight into what role

patients play in the decision-making for the adoption

of HIS and whether they should be involved in the

decision-making process. To address these gaps, we

formulate the following research questions:

RQ1. What role do patients have in decision-

making for the adoption of HIS?

RQ2. From the patient’s perspective, what are

the decision-making factors for the adoption of

HIS?

2 BACKGROUND

2.1 Patient-centred Care

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) defined patient-

centred care as “care that is respectful of and

responsive to individual patient preferences, needs,

and values” by thus ensuring “that patient values

guide all clinical decisions” (Barry and Edgman-

Levitan, 2012). This definition highlights the

importance of clinicians and patients working

together to produce the best outcomes possible.

Patient-centred care depends on the nature of

individual, professional and organizational

connections. In this manner, endeavours to advance

patient-centred care ought to consider the patient-

centeredness of patients (and their households),

clinicians, and wellbeing systems (Epstein, 2010,

Epstein et al., 2011). Helping patients to be

progressively dynamic in consultations changes years

of doctor-commanded communications to those that

draw in patients as active about what patient-centred

care truly implies, however, can create endeavours

that are specious and implausible.

Despite the discussions around patient-

centeredness, hospitals have been adopting

technologies without having discussions with the

patients (Barry and Edgman-Levitan, 2012). Besides,

while adopting technologies may upgrade the patient's

experience, they have failed to accomplish the

objectives of patient-centred care. Calls for patient-

centred care have frequently stressed the execution of

infrastructural changes (Epstein et al., 2011). These

changes, such as adopting HIS, may be necessary to

move medical care into the 21st century, but they

should not be conflated with achieving patient-centred

care. Simply implementing HIS in itself is not patient-

centred unless it strengthens the patient-clinician

relationship, promotes communication about things

that matter, helps patients know more about their

health and facilitates their involvement in their care

(Epstein and Street, 2011).

2.2 Impact of HIS

Lippeveld et al., (2000) defines HIS as “a set of

components and procedures organized to generate

information which will improve healthcare

management decisions at all levels of the health

system”. HIS has the potential to address many of the

challenges that healthcare is currently confronting.

For example, it can improve information

management, access to health services, quality and

safety of care, continuity of services, and costs

containment (Lippeveld et al., 2000).

Technological advances have encouraged the

development of new technologies that drive

connectivity across the healthcare sector such as

software apps, gadgets and systems that personalise,

track, and manage care using just-in-time information

exchanged through various patient and community

connections (Leroy et al., 2014; Carroll, 2016). This

paradigm shift has contributed to advancing healthcare

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

448

practice, highlighting our growing reliance and need of

digital care pathways to support healthcare decisions.

However, without involving patients in the decision-

making process, it may impact how patient-centred

care is received (Epstein and Street, 2011).

Digital care pathways provide the opportunity for

healthcare providers to meet the demands of high-

quality patient care and makes all-encompassing

healthcare support possible, thereby playing a

dominant role in improving health processes and in

the provision of patient care services worldwide.

2.3 Involvement of Patients in

Decision-making – Does it Matter?

Policies to encourage shared decision-making have

become prominent in the United States, Canada, and

the United Kingdom (Elwyn et al., 2010). This is partly

because of a recognition of the ethical imperative to

properly involve patients in decisions about their care

(Mulley, 2009). Shared decision-making is an approach

where clinicians and patients make decisions together

using the best available evidence. By doing so, they

likely know the benefits or harms of each so that they

can communicate their preferences and help select the

best course of action for them. Shared decision-making

respects patient autonomy and promotes patient

engagement (Elwyn et al., 2014).

Despite considerable interest in shared decision-

making, implementation has proved difficult and slow

(Légaré et al., 2008). At the minimum, three

conditions must be set up for shared decision making

to be part of mainstream clinical practice: provide

access to evidence-based information about

medication choices; direction on the best way to

weigh up the impact of various choices; and a strong

clinical culture that may encourages patient

involvement (Elwyn et al., 2010). In addition, Carroll

et al. (2016) outlined the importance of community

care and the need for more patient-centric focus in

decision-making. These authors outline some options

for creating a sustainable decision support platform

for patients that may facilitate wider adoption of

shared decision making in clinical practice.

2.4 Need for Patients Decision-making

Framework for Digital Care Pathways

According to Baker et al. (2002) “decision-making is

regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the

selection of a belief or a course of action among

several alternative possibilities”. Technology

adoption decisions in hospitals may occur through

planned acquisitions or uncontrolled changes in

medical practice. They reflect a complex set of

dynamics and incentives (Gelijns, 1992).

There are different decision-making models and

theories used to define a hospital’s decision to adopt

the technology. The first set of models include the

profit-maximization model (Focke and Stummer,

2003), and the fiscal managerial system (Lennarson

Greer, 1985). These theories presume that hospitals

assess new advancements from the viewpoint of

clinical gains, and advances obtained when the

estimated regular estimation of income surpasses the

expected expense over the valuable lifetime of the

item. Hospitals embrace capital-concentrated

advancements unrelated to their expense to

accomplish technological prevalence and to upgrade

their reputation. It helps hospitals as pioneers in the

technical domain, tempting patients, doctors, and

scientists (Anderson et al., 1994).

Nonetheless, medical administrators may often

choose to put resources into monetary loss activities

that can enhance medical exposure and draw in patients

for other parts of the hospitals (Teplensky et al., 1995).

The medical-unorthodox viewpoint (Lennarson Greer,

1985) centres around the delivery of services as per the

requirements of doctors or medical administrations. Its

likelihood depends on elementary presumptions that

the doctors and the clinic receive new technologies

dependent on the medical needs of the population they

serve, regardless of whether monetary limitations,

competition, or estimation of hospital repute

recommend alternative conducts. In contrast, hospitals

do not embrace innovation, regardless of its

exceptionally beneficial nature, if patients cannot

procure significant advantages from it.

Several other theories such as Technology–

Organization–Environment (TOE) framework

(Tornatzky et al., 1990), and Human-Organization-

Technology–fit (HOT-fit) (Yusof et al., 2008) have

been suggested to describe hospital behaviour and

adoption of new technology, yet none of these

perspectives has tried to explain technology adoption

decisions from the patient’s perspective or has

considered patients as a stakeholder (Yang et al., 2013).

3 METHODOLOGY

This study aimed to comprehensively analyse the

decision-making factors on the adoption of digital care

pathways in a hospital setting. For this purpose, we

performed a literature search, which focused on the

decision-making about the adoption of IS in general

and HIS in particular. The detailed protocol and results

of the literature review are available in our technical

A Patient’s Perspective on Decision-making for the Adoption of Digital Care Pathways

449

report (Abbas et al., 2019). Following the literature

review, we conducted exploratory interviews with

fifteen patients who were undergoing treatment in the

hospital and using HIS as part of their care pathway.

The hospital we studied is the second largest

maternity hospital in Ireland, with an average of 5,000

births per year and the sole provider of obstetrical,

midwifery and neonatal intensive care to the Mid-

West region. It is managed by the Irish Government’s

Health Service Executive (HSE) within a hospital

group. This hospital moved from phone consultation

for diabetic pregnant patients to virtual clinics which

includes video consultation with patients.

We used the methodical approach of qualitative

semi-structured interviews since they not only provide

an interviewing process that targets the identification

of the relevant determinants of the role patients can

play in the decision-making process, but it also allows

new viewpoints to emerge freely (Britten, 1995).

All the 15 interviews were recorded and

subsequently transcribed. Interviews were conducted

between February 2019 and August 2019. The ethical

approval was granted for these interviews through the

ethics committee.

Data analysis was undertaken using thematic

analysis (Guest et al., 2011). Initially, in thematic

analysis, we coded data according to key themes and

its various subcategories. All the interview transcripts

were analysed and coded, according to the guidelines

suggested by Saldaña (2015).

In the first cycle, the entire transcript was read in

detail line-by-line. We performed descriptive coding,

bearing in mind our research questions. This was

followed by relating categories to their subcategories.

We then mapped our findings according to the

literature while remaining open to the identification of

alternative and new categories of concepts. Once a

relationship was determined, the focus returned to the

data to question the validity of these relationships to

decision-making factors. Thus, by blending the

strengths of our analysis and coupling them with our

literature review, concept mapping offered a way to

represent meaning to the decision-making concept.

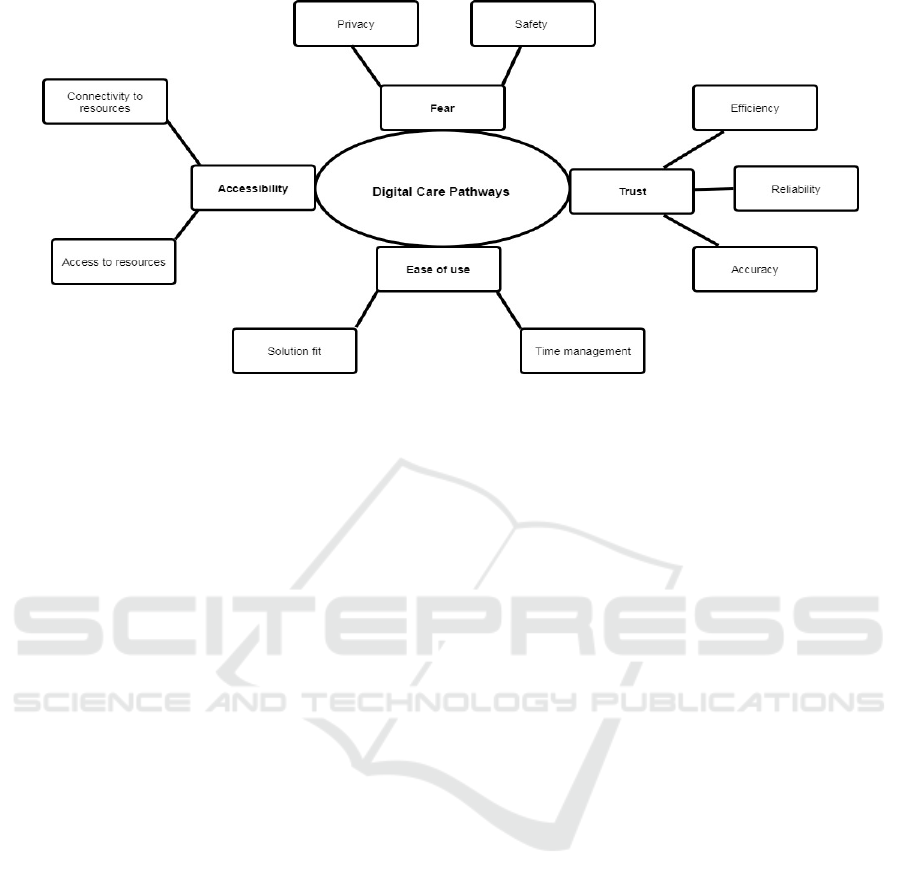

4 PATIENT DECISION-MAKING

FRAMEWORK FOR DIGITAL

CARE PATHWAYS

Lennarson Greer (1985) suggests that that the

clinicians and the hospital adopt new technologies

based on the clinical needs of the patients. While the

decision to adopt healthcare technology is based on

patients need is described, the patients are not

involved in the decision-making process. As a first

step for involving patients in the decision-making

process for the adoption of HIS, we developed the

‘Patient Decision-Making Framework for Digital

Care Pathways’ (Figure 1) that captures different

decision-making factors from the patient’s

perspective. Central to this is the idea that patients

need to be aware of the advancements in Digital Care

Pathway and how it helps them in improving their

care. In the norm, a Digital Care Pathway does not

alter how healthcare is delivered to the patients but

alters the medium of the care.

Based on the interviews, we identify patients’ key

decision-making factors for the adoption of digital care

pathways and present them through our framework.

The main contribution from our framework is that we

have identified four main patients’ decision-making

factors for the adoption of digital care pathways - trust

in the adoption of the digital care pathways, fear of

privacy and safety, ease of use of the digital care

pathways, and accessibility to healthcare. As described

earlier, there is a growing consensus that hospitals are

setup with a view to patient-centred care and one

should involve the patients in the decision-making. Yet,

we have observed a lack of involvement of patients in

decision-making for digital care pathways. Our

framework and the four factors provide an approach to

define the context of digital care pathways adoption to

support patients’ decision-making. We describe each of

the four factors and how literature supports our

framework.

4.1 Trust in Adoption of Digital Care

Pathways

Trust in technology influences the use or adoption of

a technology (Abbas et al., 2017). Trust is defined by

Amoroso et al. (1994) as a “level of confidence or

degree of confidence” and trust in technology is

defined as a “degree of confidence that the technology

satisfies its requirements”. Since the definition is

expressed as a “degree of confidence”, Amoroso et al.

illustrate that trust is dependent upon management

and technical decisions made by individuals or groups

of individuals evaluating the technology. Trust in

digital care pathways is expressed in terms of a set of

requirements, where the ‘set’ is variable. For

example, HIS trust may be dependent on the set of

functional requirements or maybe a critical subset of

functional requirements, or it may be some set of

requirements that include non- functional assurance

requirements like accuracy or reliability (Amoroso et

al., 1994).

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

450

Figure 1: Patient Decision-Making Framework for Digital Care Pathways.

Patients described three sub-factors of trust that

they deemed to be an important of the decision-

making process - reliability, accuracy and efficiency.

Van Velsen et al. (2016) discussed trust in a

rehabilitation portal technology, which was mainly

determined by its reliability. They defined reliability

for the rehabilitation portal technology as: “That it

works properly; is not constantly offline. But also

scientifically reliable”. For patients, reliability is the

probability of the technology delivering results that

are consistent with their clinicians’ understanding.

Carbone et al. (2013) defined Accuracy for HIS as

“information generated to the extent to which test

results, diagnoses and treatments are error-free”.

For patients, the accuracy of digital care pathways

was one of the decision-making factors that should be

looked into before its adoption. One of the patients

mentioned: “my first thoughts to decide virtual clinics

would be its accuracy because else I don’t want to use

virtual technology that is giving error generated

results”.

Efficiency and quality have been discussed

regularly in the literature. The efficiency of

technology is one of the decision factors defined by

(Egea and González, 2011) for a clinician’s

acceptance to use and trust technology. They explain,

“a clinician who uses healthcare technology is

concerned by the quality and efficiency of the system

which impacts the patient’s care. Effectiveness of the

technology is that it can give a quick response or

reaction with minimal resources and/or time taken”.

Patients thought the efficiency of virtual clinics is

one of the decision factors that supported the hospital

in adopting it. One patient stated that: “How can

(hospital) decide to use virtual clinics if it was not

efficient enough while managing their time and

patients as well”.

4.2 Fear of Loss of Privacy and Safety

Fear of lack of regulations around privacy and safety

of patient’s data was another factor that was

mentioned by patients as one of the main decision-

making factors to adopt virtual clinics. Researchers

who have published on this topic, advocate for

regulations to protect privacy and ensure safety.

However, patients continue to have a fear of a data

breach. For example, Hsieh (2015) describes privacy

as the potential loss of confidential patient data in

Electronic Medical Record exchange systems as a

reason for low adoption by the hospitals. Patients

interviewed were concerned by the change of General

Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) regulations and

the impact it may have on their privacy of data. When

asked about the virtual clinics decision-making factor

that they think was considered, one patient mentioned

that: “my concerns around virtual clinics decision-

making will always be around privacy of my data and

the lack of awareness given to me around it … no one

briefed or talked about it”.

Similarly, patients considered that the safety of

their treatment as one of the Hospitals decision-

making factors to adopt virtual clinics. One of the

patients had concerns around the usage and safety of

virtual clinics stating that: “this is all government

doing to facilitate hospital, they have fewer resources,

and this is all to utilize that else why would you

implement something virtually when physical

consulting is safer and makes sense to the patient”.

A Patient’s Perspective on Decision-making for the Adoption of Digital Care Pathways

451

4.3 Ease of Use of Digital Care

Pathways

Ease of use of digital care pathways refers to how

patients see ease of use and comfort in using as

leading to the adoption of digital care pathways.

Almost every patient mentioned ease of use as a

leading decision-making factor in adopting virtual

clinics. Patients see virtual clinics as a means to

provide comfort in treatment, or as a means to ease

staff workload. Barry and Edgman-Levitan (2012)

advocate for this, stating that “patients need to be

involved in determining the management strategy

most consistent with their preferences and comfort”.

It was noticed that long waiting times could be

minimized from both the patients and the healthcare

professional’s perspective. One of the patients stated

that “I have small kids, going to the hospital with them

is tough. Through virtual clinics, I have specific time

with my clinician, and I don’t have to wait in long

queues”.

4.4 Accessibility to Healthcare

The fourth patient decision-making factor that our

framework captures is accessibility. Accessibility

covers the connectivity to the resources as well as

access to the resources. Access to resources describes

how patients think implementing virtual clinics has

helped to end long queues and wait time by utilizing

less staff and space in the hospital. One of the

concerns patients had with the implementation of

virtual clinics was the thought process behind the

connectivity to access virtual clinics. Patients living in

remote areas were concerned by their internet speed

and how these virtual clinics can be assessed.

Patients who had to travel a long way applauded

virtual clinics and how it solved their problem of

travelling. Also, it was noticed that long waiting times

could be minimized from both the patients and the

healthcare professional’s perspective. One of the

patients stated that

“As a virtual entity given that our

geographic area is quite big, I find it very difficult to

come to the hospital, it makes sense to introduce this

service and to do everything virtually”.

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

Globally, patient-centred care is talked about in

modern healthcare, yet challenges remain to regularly

engage patients in decision-making. This is echoed by

Barry and Edgman-Levitan (2012), who claim that

engaging clinicians and patients in decision-making

can help to achieve quality and trust: “Recognition of

shared decision making as the pinnacle of patient-

centred care is overdue”. To build a truly patient-

centred healthcare system, we need to involve patients

in decision-making, not only about their treatments,

but also about the decisions to adopt digital care

pathways.

We also studied the role which patients play in the

decision-making for the adoption of digital care

pathways. In the case study we conducted, one of the

decision factors from hospital perspective for the

adoption of virtual clinics was on patient-centred care

and making the experience better for patients, but we

found that patients themselves did not play any role in

the decision-making for the adoption of the virtual

clinic.

Although patients were happy with the care and

did not express an interest in participating in the

decision-making for the adoption of virtual clinics,

they did contest the decisions to adopt virtual clinics

as not being patient-centred. One patient stated “I see

virtual clinics as help to midwives, it has nothing to

do with patients. If I was on private insurance, would

they have adopted virtual clinics?”.

Generally, patients were satisfied with the care

hence less concerned with the involvement in the

decision-making process. One patient stated that “I

am happy with my care so yes it makes sense that my

involvement is minimal and having no experience in

decision-making, what would I suggest anyways”.

Another patient stated that “I am not an expert so

consulting me with decision-making is not a good

option, I am happy the way my treatment has gone and

for me, the care is the only factor that matters”.

There is some evidence that when patients have

made well-informed decisions, they also follow better

treatment routines (Joseph-Williams et al., 2010).

Patients are encouraged to think about the available

screening, treatment, or management options and the

likely benefits and harms of each so that they can

communicate their preferences. As stated by Stacey et

al. (2017) “when informed patients face discretionary

treatment, they make more conservative decisions,

often deferring or declining interventions”. These

effects seem to be strengthened when patients are

given decision coaching (a brief discussion with a

trained facilitator) to help them with the process of

discussion (Joseph-Williams et al., 2010).

We have identified that there is a gap, as different

theories such as TOE, HOT-fit or the medical-

individualistic perspective do not involve patients in

the decision-making for the adoption of digital care

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

452

pathways. Therefore, we introduce the patient

decision-making framework for digital care pathways

which covers the patient’s perspective in the decision-

making process.

5.1 Future Work

Having established a foundation for the patient

decision-making framework for digital care

pathways, we will continue to build on this to

establish key processes and factors to further develop

the decision-making framework that includes both the

hospital staff and patient perspective of decision-

making factors for the adoption of digital care

pathways. The concept of a digital care pathway may

broaden the concept of how the medium of care for

the patients be enhanced.

We present the framework as a first step that

encapsulates research developments across patient-

centred care and recognise a need for empirical

research to validate patient decision-making. Our

subsequent focus will be on extending and modifying

existing techniques based on the identified patient

factors during our analysis. Furthermore, we will test

and refine it on a large scale with the healthcare sector.

One of the limitations of this study is the limited

number of patients interviewed. As this is a project in

progress, we are interviewing additional patients to

strengthen our findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported with the financial support of

the Science Foundation Ireland grant 13/RC/2094 and

co-funded under the European Regional Development

Fund through the Southern & Eastern Regional

Operational Programme to Lero - the Irish Software

Research Centre (www.lero.ie).

REFERENCES

Abbas, R. M., Carroll, N., Richardson, I. and Beecham, S.,

2017. The Need for Trustworthiness Models in

Healthcare Software Solutions. BIOSTEC 2017, Vol. 5,

pp. 451-456.

Abbas, R. M., Carroll, N., Richardson, I., "Protocol for a

Structured Literature Review of Decision-making Factors

for the Adoption of Health Information Systems 2019".

Available at: https://www.lero.ie/sites/default/files/TR_

2019_02.

Amoroso, E., Taylor, C., Watson, J. and Weiss, J., 1994,

November. A process-oriented methodology for

assessing and improving software trustworthiness. In

Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Conference on Computer

and communications security pp. 39-50.

Anderson, G., E. P. Steinberg, and H. Dawkins 1994. "Role

of the Hospital in the Acquisition of Technology."

Medical Innovation at the Crossroads 4: pp. 61-70.

Aron, R., S. Dutta, R. Janakiraman and P. A. Pathak 2011.

"The impact of automation of systems on medical

errors: evidence from field research." Information

systems research 22(3): pp. 429-446.

Baker, D., D. Bridges, R. Hunter, G. Johnson, J. Krupa, and

K. Sorenson 2002. "Guidebook to decision-making

methods." Department of Energy, USA.

Barry, M. J. and S. Edgman-Levitan 2012. "Shared Decision

Making — The Pinnacle of Patient-Centered Care."

New England Journal of Medicine 366(9): pp. 780-781.

Britten, N. 1995. "Qualitative research: qualitative interviews

in medical research." Bmj 311(6999): pp. 251-253.

Carbone, M., Christensen, A. S., Nielson, F., Nielson, H. R.,

Hildebrandt, T. and Sølvkjær, M., 2013, August. ICT-

powered Health Care Processes. In International

Symposium on Foundations of Health Informatics

Engineering and Systems pp. 59-68. Springer Berlin

Heidelberg.

Carroll, N., 2016. Key success factors for smart and connected

health software solutions. Computer, 49(11), pp. 22-28.

Carroll, N., Kennedy, C. and Richardson, I. 2016

‘Challenges towards a Connected Community

Healthcare Ecosystem (CCHE) for managing long-term

conditions’, Gerontechnology, 14(2), pp. 64–77.

Delbanco, T. and Gerteis, M. 2012 ‘A patient-centred view

of the clinician-patient relationship’. Available at:

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/a-patient-centered-

view-of-the-clinician-patient-relationship (Accessed:

10 December 2019).

Egea, J. M. O. and M. V. R. González 2011. "Explaining

physicians’ acceptance of EHCR systems: an extension

of TAM with trust and risk factors." Computers in

Human Behavior 27(1): pp. 319-332.

Elwyn, G., S. Laitner, A. Coulter, E. Walker, P. Watson and

R. Thomson 2010. "Implementing shared decision

making in the NHS." BMJ 341: pp. 5146.

Epstein, R. M., K. Fiscella, C. S. Lesser and K. C. Stange

(2010). "Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-

centered health care. "Health affairs 29(8): pp. 1489-1495.

Epstein, R. M. and R. L. Street 2011. The values and value

of patient-centered care, Annals Family Med.

Focke, A. and Stummer, C., 2003. Strategic technology

planning in hospital management. Or Spectrum, 25(2),

pp.161-182. doi: org/10.1007/s00291-002-0118-y

Gelijns, A. C. 1992. Technology and health care in an era of

limits, National Academies Press.

Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J. Through the

patient’s eyes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1993.

Gravel, K., Légaré, F. and Graham, I. D. 2006 ‘Barriers and

facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in

clinical practice: A systematic review of health

professionals’ perceptions’, Implementation Science.

doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-16.

Guest, G., K. M. MacQueen and E. E. Namey 2011. Applied

thematic analysis, Sage Publications.

A Patient’s Perspective on Decision-making for the Adoption of Digital Care Pathways

453

Hsieh, P.-J. 2015. "Physicians’ acceptance of electronic

medical records exchange: An extension of the

decomposed TPB model with institutional trust and

perceived risk." International Journal of Medical

Informatics 84(1): pp. 1-14.

Ismail, N. I., N. H. Abdullah, and A. Shamsuddin, Adoption

of Hospital Information System (HIS) in Malaysian

Public Hospitals. Procedia - Social and Behavioral

Sciences, 2015. 172: pp. 336-343.

Izzatty Ismail, N., Abdullah, H. and Shamsuddin, A. 2015

‘Adoption of Hospital Information System (HIS) in

Malaysian Public Hospitals’, Procedia-Social and

Behavioral Sciences, 172, pp. 336–343.

Joosten, E. A., L. DeFuentes-Merillas, G. De Weert, T.

Sensky, C. Van Der Staak and C. A. de Jong 2008.

"Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-

making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and

health status." Psychotherapy and psychosomatics

77(4): pp. 219-226.

Joseph-Williams, N., R. Evans, A. Edwards, R. G. Newcombe,

P. Wright, R. Grol and G. Elwyn 2010. "Supporting

informed decision making online in 20 minutes: an

observational web-log study of a PSA test decision aid."

Journal of medical Internet research 12(2): e15.

Lennarson Greer, A. 1985 ‘Adoption of Medical Technology:

The Hospital’s Three Decision Systems’, Article in

International Journal of Technology Assessment in

Health Care. doi: 10.1017/S0266462300001562.

Légaré, F., S. Ratté, K. Gravel and I. D. Graham 2008.

"Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared

decision-making in clinical practice: update of a

systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions."

Patient education and counseling 73(3): pp. 526-535.

Leroy, G., H. Chen and T. C. Rindflesch 2014. "Smart and

Connected Health [Guest editors' introduction]." IEEE

Intelligent Systems 29(3): pp. 2-5.

Lippeveld, T., R. Sauerborn and C. Bodart 2000. Design and

implementation of health information systems, Citeseer.

Mulley, A. G. 2009. "Inconvenient truths about supplier

induced demand and unwarranted variation in medical

practice." Bmj 339: b4073.

Saldaña, J. 2015. The coding manual for qualitative

researchers, Sage.

Stacey, D., F. Légaré, K. Lewis, M. J. Barry, C. L. Bennett,

K. B. Eden, M. Holmes-Rovner, H. Llewellyn-Thomas,

A. Lyddiatt and R. Thomson 2017. "Decision aids for

people facing health treatment or screening decisions."

Cochrane database of systematic reviews (4).

Teplensky, J. D., M. V. Pauly, J. R. Kimberly, A. L. Hillman

and J. S. Schwartz 1995. "Hospital adoption of medical

technology: an empirical test of alternative models."

Health services research 30(3): pp. 437.

Tornatzky, L. G., M. Fleischer and A. K. Chakrabarti 1990.

Processes of technological innovation, Lexington books.

Van Velsen, L., S. Wildevuur, I. Flierman, B. Van

Schooten, M. Tabak and H. Hermens 2016. "Trust in

telemedicine portals for rehabilitation care: an

exploratory focus group study with patients and

healthcare professionals." BMC medical informatics

and decision making 16(1): pp. 11.

Yang, Z., A. Kankanhalli, B.-Y. Ng and J. T. Y. Lim 2013.

"Analyzing the enabling factors for the organizational

decision to adopt healthcare information systems."

Decision Support Systems 55(3): pp. 764-776.

Yusof, M. M., J. Kuljis, A. Papazafeiropoulou and L. K.

Stergioulas 2008. "An evaluation framework for Health

Information Systems: human, organization and

technology-fit factors (HOT-fit)." International journal

of medical informatics 77(6): pp. 386-398.

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

454