DLT-based Tokens Classification towards Accounting Regulation

Luz Parrondo

1,2

1

UPF Barcelona School of Management, Bames 132, Barcelona, Spain

2

Pompeu Fabra University, Ramon Trias Fargas 18, Barcelona, Spain

Keywords: DLT, Blockchain, Cryptocurrencies, Crypto-assets, Tokens, Stablecoin, Accounting Regulation.

Abstract: Distributed Ledger Technologies (DLT) are distributed, secured and immutable ledgers that allow technology

to intermediate and empower new ecosystem-based business models. DLT-based tokens digitally represent a

wide variety of assets from securities to commodities or merely as means of payment within a DLT network.

However, DLT-tokens may (alternatively or jointly) grant digital access to a DLT platform, serve as

incentivation system or as a right for future consumption of goods or services. The aim of this paper is to

provide a first definition, classification and guidance for accounting treatment of the DLT-based tokens. The

paper proposes four factors as determinants to classify digital tokens as payment tokens, utility tokens and

security tokens. Factor number one is the existence of a legal right against a counterparty; second, the

existence of value stability; third, the existence of intrinsic value; and forth, existence of investment risk for

the token-holder. First, the analysis suggests that tokens failing to comply with the first and second condition

classify as payment tokens. These payment tokens subdivide into stablecoins and cryptocurrencies if

alternatively satisfy the third (value stability) or fourth condition (investment risk). Second, tokens that satisfy

the first, second and third condition classify as utility tokens. And finally, tokens satisfying the first, third and

fourth condition classify as security tokens. Furthermore, the paper provides with initial guidance for

accounting treatment in each category

1 INTRODUCTION

Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT), is distributed

system is a distributed, secured and immutable ledger

that has allowed technology to intermediate and entrust

transactions (Lemieux, 2016; Klaus, 2017; Smit,

Buekens, & Plessis, 2016; Swan, 2017; Chen, 2018). It

originally allowed Bitcoin to become a “peer-to-peer

electronic cash system” (Nakamoto, 2008) and since

then hundreds of new projects have emerged that use

blockchains in a variety new and innovative ways.

Business implementation of DLT such as Blockchain,

Tempo or Dag, are still at their early stage.

We are increasingly living in digital networks,

spending an average of 11 hours a day on screens in the

US with over half of that on internet connected devices,

and growing 11% each year (Forbes, 2019). However,

in the current model, most of the decision power and

value of a network concentrates in one institution or

company (e.g. Facebook, Amazon, Alibaba). DLTs are

emerging as the new global digital infrastructure

allowing the opportunity to create vastly different

power structures (Ehrsam, 2017) McKnight et al.

(2017). Distributed technologies represent an

opportunity for regulators and policymakers to shape

the development of disruptive innovation.

Token economies have been used for centuries

and have evolved notably to systems used today.

These incentives-based structures were created and

sustained in a variety of cultures and as part of many

institutions within those cultures. Governments used

the influencing abilities of rewards to shape behaviors

in battle and throughout society. Modern research

peaked in the 1970s where there was substantial study

surrounding psychiatry, clinical psychology,

education, and mental health fields (Kazdin, 1977).

Winkler (1972) suggest the similarities between

token and national economies as “in both token

economies and national economies, consumption

schedules show that expenditures typically rises with

income and that expenditure approximates a linear

function of income over most income ranges”. As

digital economies develop, they are integrating the

concept of token economy as the engine fuel. The

Token-economics, however go one step further as it

refers to the system of incentives based on digital

tokens that reinforce and build desirable behaviours

the in a DLT-based ecosystem. Completing

Parrondo, L.

DLT-based Tokens Classification towards Accounting Regulation.

DOI: 10.5220/0008937600150026

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business (FEMIB 2020), pages 15-26

ISBN: 978-989-758-422-0

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

15

consensus in a DLT platform requires for example

miners to provide validation service for transactions.

Token-economics is the mechanism to incentivize

miners to provide better service on the network.

Academic research on this field is almost

inexistent, and we lack the basic definition for DLT-

based tokens, description of their characteristics and

functionalities, classification determinants and how

these features affect the rights and protection of token-

holders. Growing in this body of research will largely

contribute to accounting and financial literature.

A token can represent the development of a

network, secure unforgeable coupons, and even token

systems with no ties to conventional value at all, used

as point systems for incentivization. Given the wide

variety of tokens and token-sale set-ups, it is not

possible to generalize. Circumstances must be

considered in each individual case. The technical

layer, purpose, underlying asset, functionality and

legal status of the tokens determines their

classification (Euler, 2018). Regulation and

accounting treatment should depend on the properties

and rights that each token entitles based on ifs

functionality and intrinsic nature.

The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory

Authority (FINMA) has provided initial guidelines to

classify and regulate digital tokens. FINMA’s

classification of tokens into payment, securities and

utilities is becoming widely accepted among early

regulators and techno-practitioners around the world.

Based on the legal status, tokens may act as means of

payment (payment tokens), as means to exchange

value in an ecosystem providing access to products,

services, or incentives (utility tokens) or as means to

represent financial assets such as participations in

companies entitled of earnings streams, such as

dividends or interest payments (security tokens).

First, payment tokens act as store of value and

medium of exchange. Currently, these payment

tokens are not regarded as legal tender; however, they

act as means of payment. Second, security tokens

provide token-holders rights to a share of specific

revenue stream, such as dividends (equity tokens) or

interests (debt tokens), and which value derives from

an external, tradable asset, and they are subject to

federal securities regulations. If a company meets all

the regulatory obligations, the security token

classification creates the potential for a wide variety

of applications, the most promising of which is the

ability to issue tokens that represent shares of

company stock. Third, utility tokens accredits token-

holders future access to the products or services in the

issuing network or ecosystem. Some of these tokens

also grant purchasers the right to access a given

technology or to participate in an organization

providing governance rights, such as the right to vote.

The defining characteristic of a utility token is a token

not designed as an investment or a source of funding;

if properly structured, this feature exempts utility

tokens from federal laws governing securities. By

creating utility tokens, a company can sell ‘digital

coupons’ for the developing service. For example,

Filecoin, raised $257 million by selling tokens that

will provide users with access to its decentralized

cloud storage platform. Note that utility token

creators usually refer to these crowdsales as token

generation events (TGEs) or token distribution events

(TDEs) to avoid the appearance that they are

engaging in a securities offering. The confusion

however arises when these tokens can be traded in the

exchangers and provide with relevant capital gains or

losses to the token holders due to the high volatility

of the token prices in the secondary markets. In

practice, these TGEs or TDEs can be perceived as a

mean to circumvent securities governing regulations

reducing the quality of investor’s rights.

Due to the lack of homogeneity, the status of

tokens under regulatory framework is ambiguous.

This paper contributes to define and classify DLT-

based tokens, to be the first to identify four key

aspects or determinants to classify tokens as payment,

utility or security tokens; and to be the first to

articulate the correspondent accounting treatment.

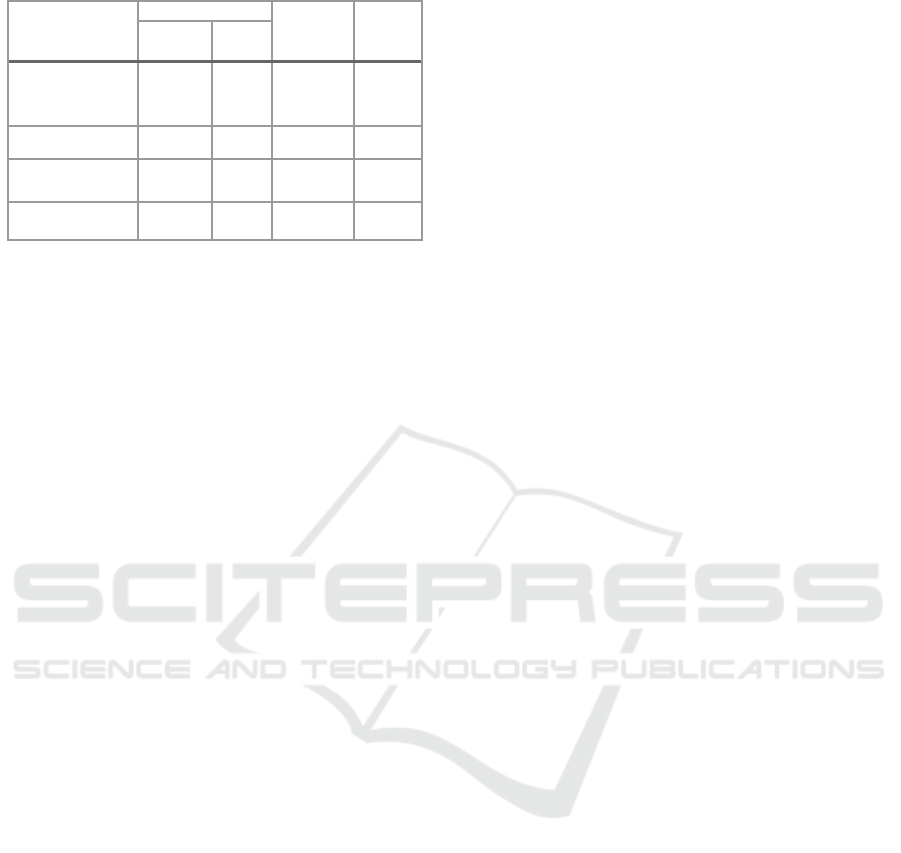

This study suggests four factors as classifying

determinants (see Table 1): (1) existence of a legal

right against a counterparty; (2) existence of intrinsic

value; (3) token-value stability; and (4) the existence

of investment risk for the token-holder . We define

the existence of a legal right against a counterparty

(1) as a claim recognizable and enforceable at law

against an entity on a given agreement. Intrinsic value

(2) is defined as the value of the underlying project

captured by a token, which is also what ensures that

the price of the token grows alongside

adoption/success of such underlying project. A token

lacking utility will see its price supported only by

speculation. Token-value stability (3) refers to a

sufficiently stable value of the token to allow its use

as means of payment or exchange of value within an

ecosystem without significant gains or losses for the

token-holder. Finally, investment risk (4) refers to the

speculative nature of the token as the token holder is

subject to uncertainty on expected profits (losses)

from the effort of others, uncertainty on future

performance, uncertainty on the possibility of

exchanging the token for fiat money or promised

goods or services.

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

16

Table 1: Determinants for token classification.

Proposed

Determinants

Payment token

Utility

token

Security

token

Crypto-

currency

Stable

coin

Legal right

against a

counterpart

y

NO NO YES YES

Intrinsic value NO NO YES YES

Token-value

stabilit

y

NO YES YES NO

Investment Risk YES NO NO YES

First, the lack of any legal right against a

counterparty, absence of intrinsic value and lack of

investment risk classifies a token as a payment token,

enabling these tokens as store of value and as a means

of payment. However, for payment tokens to perform

as efficient means of payment volatility should be

relatively low. We find certain highly volatile tokens,

such as Bitcoin, which are not efficient means of

payment. Although they can be use as such, high

volatility disqualifies them to effectively perform,

and introduces investment risk. We propose to divide

payment tokens into two sub-categories, stablecoins

and cryptocurrencies. Second, utility tokens provide

legal rights for the holder against the DLT-network

issuer; they have intrinsic value (due to its

functionality) and value stability, which qualifies

them as means of value exchange within a DLT

ecosystem. Functionality is by definition the purpose

of a utility token, investment risk should therefore be

absent from these type of tokens. Finally, security

tokens have contractual claims, have intrinsic and

speculative value, waiving out value stability and

introducing investment risk.

The above individual token classifications are not

mutually exclusive. Security and utility tokens can

also be classified as payment tokens (referred to as

hybrid tokens). In these cases, the requirements are

cumulative; in other words, the tokens are deemed

both securities and means of payment.

2 DLT, BLOCKCHAIN AND

IMPLICATIONS FOR

BUSINESS ECOSYSTEMS

Blockchain has been referred to as a Distributed

Ledger Technology where the terms have been used

interchangeably, however, blockchain is a subset of

DLTs that is under the umbrella of distributed

databases. Distributed systems are a computing

paradigm whereby two or more nodes work with each

other in a coordinated fashion to achieve a common

outcome. It is modelled in such a way that end users

see it as a single logical platform. For example,

Google's search engine is based on a large distributed

system, but to a user, it looks like a single, coherent

platform (Bashir, 2018). These systems are designed

to be fault tolerant in case of the failure of some nodes

where information is duplicated and stored in

multiple physical locations. Furthermore, nodes on

distributed systems have to validate information

individually and create the entire transactions history

independently to ensure honesty where trust is not

considered. DLTs are based on Byzantine-fault

tolerance (Lamport, Shostak, & Pease, 1982) where

the system will still run and function regardless of the

failure, dishonesty or the suspicion of malicious

nodes. DLTs depends on transparency, replicating

data across all the interconnected nodes to compare,

validate and vote/agree to secure the accuracy of data

and records

Transactions are stored in order by time in a single

ledger on the blockchain. Having a transaction history

has multiple benefits in terms of increased regulatory

compliance and being able to recourse to the system

to at any point in time. The use of digital signature

makes it impossible for any “outsider” (i.e. hacker) of

gaining access into the system. Moreover, the

fundamental feature that makes this system attractive

and stand out from other technologies is the

immutability and trust lessness of this system, where

data cannot be forged once it has been recorded on the

ledger, nor fabricated. Miners cannot transfer assets

or records without the consent (i.e. digital signature)

of the owner/participant, manipulation or other nodes

can detect fraud immediately.

Technologist and practitioners in general have

entered the debate whether centralized platforms fit

into the blockchain definition. This debate falls out of

the scope of this paper and this is why we use the

broader concept of DLT instead of blockchain.

DLTs could have serious implications for the future

of business. From accounting to operations, the

growing consensus among industry leaders and

researchers is that blockchain and other similar DLTs

are likely to affect every major area of society. The

blockchain initially became very popular in finance

where transparency, trust, and security in transactions

are vital (Economist, 2015). This technology does not

require (however may have) any intermediary such as

a central bank to ensure trust and security in

transactions (Buterin, 2013, Economist, 2015,

Nakamoto, 2008) and are also more cost-efficient in

micro-transactions compared to traditional

DLT-based Tokens Classification towards Accounting Regulation

17

mechanisms (Buterin, 2014b). Radiating

trustworthiness through third parties is replaced by

understanding the blockchain technology and seeing

what the status of the transaction is. In other words,

instead of trusting that a transaction will be conducted

as agreed upon, now one can see the status of the

transaction and knows what is going on. However, the

DLTs does not only support financial transactions, they

can support all kinds of tokens units of value. Digital

assets such as shares, contracts, and stock options have

been traded on the blockchain as well. Thus, all kinds

of economic systems or more specifically, trading of

property rights, benefit from such a trust-free, secure,

and transparent transaction system (Beck, Stenum

Czepluch, Lollike, & Malone, 2016).

The previous analysis suggests that DLTs

(blockchain included) may grant more efficient to

existing business structures and processes, however

the most promising disruption may rise from the

tokenization of value in the DLT-embedded structure

of token economics.

3 TOKEN DEFINITION AND

CLASSIFICATION

Definition of DLT-based token is not trivial. Most

research has focused on the definition of Bitcoin, or

Blockchain (Fosso Wamba, Kala Kamdjoug, Epie

Bawack, & Keogh, 2018), with a lack of consensus in

its definition. The extended definition of digital

tokens is even more scant. Pakrou and Amir (2016)

define Bitcoin as ‘a virtual and crypto-currency based

on a peer-to-peer network, digital signatures and zero

knowledge proof that allows the users to do

irreversible money transfer without any

intermediate’. Furthermore, Meiklejohn et al. (2016)

define Bitcoin as ‘a purely online virtual currency,

unbacked by either physical commodities or

sovereign obligation; instead, it relies on a

combination of cryptographic protection and a peer-

to-peer protocol for witnessing settlements’.

Macedo’s (2018) wider approach defines a token as a

crypto-economic unit of account that represents or

interacts with an underlying value-generating asset. A

token’s value is made up of its intrinsic value and its

speculative value. The intrinsic value is the

percentage of the token’s value that derives from

demand for the underlying asset. The speculative

value is the percentage of the value of the token that

derives from demand due to an expectation of future

price increases. A token’s intrinsic value is dependent

on two factors: the value created by the underlying

asset and the percentage of this value that is captured

by the token. The token economic model is what

determines the latter — how much of the value

created by the platform is captured by the token.

However, DLT-based tokens are broader than this

definition. Tokens may simply provide access to a

specific application or business platform and

essentially function like an alternative password

alternatively, the tokens may include any form of a

relative right against a third party. The relative right

might be a (legal) right to use the token generator’s

goods or services, a right to receive a financial

payment, a right to receive an asset or a bundle of

shareholder’s right, or provides technical ownership

rights in assets (MME Legal | Tax | Compliance,

2018).

Following these definitions, this paper suggests a

broader definition for tokens, as a crypto-economic

unit of account based on a DLT network that

represents or interacts with an underlying value-

generating right. The value transfer can range from

simple payments to property, financial assets, or any

type of right or obligation likely to be tokenized and

transferred through a DLT network.

Bitcoin, and bitcoin protocol (Nakamoto, 2008)

was the birth of Blockchain technology. The primary

use of tokens in the bitcoin protocol was as a means

of compensating parties for the consensus

mechanism. As now, in some public blockchains, a

valid hash for a block must have a predefined number

of leading zeroes, which can only be generated

through a computationally power consumer guessing

game called proof of work. The process involves

scanning for a value that when hashed, (such as with

SHA-256), the hash begins with a number of zero

bits. The average work required is exponential in the

number of zero bits required and can be verified by

executing a single hash. In simple words, Proof of

work is an expensive computation done by all miners

to compete to find a number that, when added to the

block of transactions, causes this block to hash to a

code with certain rare properties. Finding such a rare

number is hard (based on the cryptographic features

of the hash function used in this process) however

verifying its validity is relatively easy. Miners engage

in this game in exchange of tokens. However, the use

of the token goes further than a reward system in the

bitcoin protocol, it serves as the unifying purpose of

the whole network. The network exists to create and

transfer these tokens after they are forged from the

computer hardware and the electricity needed to

facilitate bitcoin transactions. The Bitcoin token

serves as a rough approximation of the expected value

and total support for the bitcoin network as a whole.

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

18

The more miners that choose to support the network,

the harder and more expensive it becomes to create a

Bitcoin, thus providing a basis for a Bitcoin’s value,

as mining costs and time impact demand and supply,

thus value (Xu, y otros, 2016). Bitcoin was the first

cryptocurrency, and the system on which its tokens

work serves only for this type of tokens.

After Bitcoin, the universe of digital tokens

increased. With the introduction of Ethereum in 2015

came the concept of SC. The Ethereum blockchain

not only provided the infrastructure for transacting

primitive digital tokens, but also provided the

capability for easily creating and autonomously

managing other digital tokens of value over the open

public network without trusted intermediaries.

Ethereum and similar, can be considered a second-

generation blockchain. These platforms like Bitcoin,

enable its members to store information in a tamper

resistant, highly resilient, and non-repudiable manner

and have a native protocol token ether that reward

miners for generating valid blocks for the Ethereum

blockchain. Ethereum, however, intends to

implement a more energy efficient protocol of

consensus then proof of work, called proof of stake

(announced for implementation in January 2020).

Moreover, Ethereum goes one-step further

implementing ‘smart’ contracts capable of being self-

executed and self-enforced autonomously and

automatically, without intermediaries or mediators.

SC are ‘scripts’ (computer codes) written with

programming languages whereby the terms of the

contract are sentences and commands emulating the

logic of contractual clauses which enables anyone on

the network to execute actions. Ethereum requires

that users of the network seeking to execute a SC pay

miners a fee (called ‘gas’) for each computational

step in the SC. These fees are necessary for Ethereum

to run SC programs because, without them, members

of the network could choke the network with spurious

requests that would prevent SCs from executing. The

token, therefore, serves as a form of ‘crypto fuel’

needed for the network to operate. We can program

the creation of a token and associate its effects with

(1) the creation of new tokens or (2) specific rights

and obligations raised due to then SCs. Using this

concept of SCs, which are effectively applications

running on top a decentralized network, tokens can be

created and allocated to users, and made to be easily

tradable.

Initially, classification of tokens was unclear and

the process of issuing any type of token and

distributing them to users was called Initial Coin

Offering (ICO). Later, as most of the tokens offered

were classify by financial authorities as securities a

new term emerged, Security Token Offering, or an

STO. An STO is the proper term to refer to a token

crowd sale, in which consumers purchase blockchain-

based crypto tokens. Whereas ICO remains in use, it

is a dubious term referring to the sale of tokens, with

no clear distinction on the legal nature of the

underlying tokens, on the other hand, STOs make

clear reference to the sale of digital securities. Tokens

may be issued similarly to the issuance of financial

instruments. A security or financial instrument is a

contract, which represents an asset to the holder and

a liability to the issuer. The stocks, bonds, loans,

derivatives (options, swaps, futures ...) or even money

are financial instruments and tokens analogous to

these instruments are already being issued daily on

the internet and they are being financed (‘bought’)

mostly with Bitcoin and Ether. However, tokens may

be created to seed network effects tokenizing values

such as the user’s reputation within a system (e.g.

augur reference), an incentive to increase storage

space (e.g. Filecoin) or use tokens for on-chain voting

as a decision mechanism. Most applications or SCs

operate with tokens as means of governance. For

example, the decision-making process may rely on

having token holders vote according to the amount of

owned tokens (Ruiz, 2017), tokens such as Ethers,

ICONs or EOS may provide access to enhanced

functionality infrastructure. Thus, a token can fulfil

either one, or several of the following functions: (1)

A digital currency, (2) a digital right within a

blockchain ecosystem and (3) a digital security.

It is relevant for analysts, regulators and investors

to clearly separate and differentiate functionality and

rights when referring to tokens. As stated, we can

classify tokens into three main groups, payment

tokens, security tokens and utility tokens.

3.1 Payment Tokens

There are several attempts to define Payment tokens

across recent literature. Tu and Meredith (2015)

define Bitcoin, the as ‘a medium of exchange that is

electronically created and stored, and lacks the

backing of a government authority, central bank, or a

commodity like gold’. Sklaroff (2017) defines it as ‘‘a

cryptocurrency built using distributed ledger

technology (DLT) protocols to enable participants to

create, store, and exchange money itself’’. FinCEN

has stated that a ‘virtual currency is an exchange

mechanism that exists in electronic form and acts like

currency in some environments (such as electronic

transactions)’. However, payment tokens do not have

the attributes of legal tender in any jurisdiction

(Fisher & Kaplinsky, 2013; Goodwin Procter, 2014).

DLT-based Tokens Classification towards Accounting Regulation

19

Governmental institutions across countries have

officially accepted that virtual currencies such as

Bitcoin can be a ‘legal means of exchange’. Examples

of Payment tokens are Bitcoin (BTC) with is a purely

transactional currency, Zcash (ZEC), Monero (XMR)

or Litcoin (LTC). Christopher (2014) describes the

main characteristics of these tokens as: (1) they act

as a store of value and medium of exchange; (2) no

central authority issuance; (3) currently they are not

considered legal tender; (4) they have no legal

counterparty and (5) they are not regulated under

money laws although they have to comply with

KYC/AML

rules. Interestingly, already in 2013, the

US Department of Treasury issued an interpretive

guidance to address the applicability of AML rules to

persons creating, obtaining, distributing, exchanging,

accepting, or transmitting virtual currency. The

guidance provided information to help taxpayers

determine whether their activities with virtual

currencies classify them as a money services

business, which are types of nonbank financial

institutions that are regulated by the Bank Secrecy

Act (BSA).

Currently, Payment tokens are an inefficient

medium of exchange due first to technological

limitations on the trading and validation process

which affect the daily volume of transactions that are

significantly lower than traditional currencies.

Second, high volatility makes it impossible for users

to rely on the virtual currencies as a means of

maintaining value. In 2013, the volatility of Bitcoin

was substantially higher than both currency and stock

volatility (Swartz, 2014). The value of a token has

two components, the speculative value and the

intrinsic value. The intrinsic value of a token is a

mechanism through which the value of the token can

be realistically evaluated. By linking it with the value

of the legal tender, it is possible to give intrinsic value

to tokens. Recently Facebook has released the Libra

White Paper. Libra is backed by real world assets.

This reserve of assets is a collection of low-volatility

assets, including cash and government securities from

stable and reputable central banks, giving a security

of rewards to users (The Libra Blockchain, 2019).

These types of DLT-based tokens are called

stablecoins. Stablecoins may be divided into two

main stability mechanism categories: algorithmic and

asset backed. A recent report from Blockcahin.com

(The State of Stablecoins, 2019) finds that 54% of

asset-backed stablecoins, utilize on-chain collaterals

(i.e., digital currencies like ether) and 46% use off-

chain collaterals (i.e., US dollars held in escrow). US

dollar is the most common stability benchmark or

‘peg’ and is utilized by 66% of stablecoins; other

benchmarks include other fiat currencies (e.g., euro,

yen), commodities (e.g., gold), and inflation (e.g.,

G10 average country inflation). Other requirements to

maintain value stability is to work with a competitive

group of exchanges and other liquidity providers, to

secure that users can be able to sell the stablecoin at

or close to the expected value at any time. This

provides the coin intrinsic value reducing volatility

and protects the coin against the speculative swings

of other cryptocurrencies.

Payment token’s volatility has prevented them to

be used as medium of exchange for short-term use.

Therefore, pegging them to commodities facilitates

their use as global currency regardless of being issued

by a central bank. Stablecoins might be the initial

solution to incentivize trust in payment tokens as

means of payment as the gold standard provided trust

in the 19th and beginning of the 20

th

century. USD

coin (USDC) is an example of a stablecoin that is a

digital token built on the bitcoin blockchain fully

backed by fiat currency, the US Dollar. USDC

enables fiat currencies existence on the public

blockchain in a tokenized form that adheres to

governmental laws and regulations. The conversion

rate of USDC to fiat currency is 1:1 making it

equivalent to the underlying currency it represents

and redeemable for cash that equals of the value the

underlying assets holds. USDC and similar, act as

bridge to satisfy the crypto world to creating a more

stable currency, this does, however, raise the question

of the continuous need for trust as it still relying on a

centralized financial system to guarantee their

stability and coexistence on the platform.

Technologists have open an interesting debate

whether stablecoins (such as Theter) fall into de

definition of cryptocurrency, like Bitcoin. The

relevant difference between both cryptocurrencies

and stablecoins is volatility. Previous analysis

suggests that both are payment tokens, however

Bitcoin’s high volatility affects its effectiveness as

means of exchange. This article suggests opening a

sub-division within the payment tokens as

cryptocurrencies, for high volatility payment tokens,

and stablecoins for tokens which anchor their value

to avoid undesired volatility.

In general terms, the two determinants that

discriminates payment tokens from utility and

security tokens are: (1) absence of counterpart; and

(3) absence of intrinsic value. We propose the

following definition for payment tokens: Payment

tokens a crypto-economic unit of account, with no

legal counterparty, and no intrinsic value which

acts as means of exchange, unit of account and

store of value providing access to an underlying

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

20

DLT platform. Payment tokens subdivide in two

subcategories depending on (2) value stability and (4)

investment risk.

3.1.1 Subcategory of Cryptocurrencies

Following these requirements, Yemark (2015)

suggests that Bitcoin somewhat meets the first of

these criteria, because a growing number of

merchants, especially in online markets, appear

willing to accept it as a form of payment. However,

the worldwide commercial use of bitcoin remains

minuscule, indicating that few people use it widely as

a medium of exchange. Further the author argues that

bitcoin performs poorly as a unit of account and as a

store of value. Bitcoin requires merchants to quote the

prices of common retail goods out to four or five

decimal places with leading zeros, a practice rarely

seen in consumer marketing and likely to confuse

both sellers and buyers in the marketplace. Bitcoin

exhibits very high time series volatility and trades for

different prices on different exchanges without the

possibility of arbitrage, and failing to provide the

expected risk-free returns (Bordo & Levin, 2017). All

of these characteristics tend to undermine bitcoin’s

usefulness as a unit of account. As a store of value,

bitcoin faces great challenges due to rampant hacking

attacks, thefts, and other security-related problems.

Bitcoin’s daily exchange rate with the U.S. dollar

exhibits virtually zero correlation with the dollar’s

exchange rates against other prominent currencies

such as the euro, yen, Swiss franc, or British pound,

and also against gold. Therefore, bitcoin’s value is

almost completely untethered to that of other

currencies, which makes its risk nearly impossible to

hedge for businesses and customers and renders it

more or less useless as a tool for risk management.

A report from the Bank of International

Settlements (BIS, 2018) forewarns about the energy

and scalability limitations of cryptocurrencies, which

adds to the poor performance of cryptocurrencies on

these functions. First, the enormous cost of generating

decentralized trust. One would expect miners to

compete to add new blocks to the ledger through the

proof-of-work until their anticipated profits fall to

zero. Individual facilities operated by miners can host

computing power equivalent to that of millions of

personal computers. The total electricity use of

bitcoin mining equalled that of mid-sized economies

such as Switzerland, and other cryptocurrencies also

use ample electricity. Put in the simplest terms, the

quest for decentralized trust has quickly become an

environmental disaster. Second, cryptocurrencies

simply do not scale like sovereign moneys. At the

most basic level, to live up to their promise of

decentralized trust cryptocurrencies require each and

every user to download and verify the history of all

transactions ever made, including amount paid, payer,

payee and other details. With every transaction

adding a few hundred bytes, the ledger grows

substantially over time.

Although both constrains suggest of

cryptocurrencies not fully adequate as an everyday

means of payment, technology might eventually

overcome both limitations. BIS highlights that the

shortcomings of cryptocurrencies in this respect lie in

the volatility of its value, which arises from the

absence of a central issuer with a mandate to

guarantee the currency's stability. Well run central

banks succeed in stabilizing the domestic value of

their sovereign currency by adjusting the supply of

the means of payment in line with transaction

demand. They do so at high frequency, in particular

during times of market stress but also during normal

times. This contrasts with a cryptocurrency, where

generating some confidence in its value requires that

supply be predetermined by a protocol. This prevents

it from being supplied elastically. Therefore, any

fluctuation in demand translates into changes in

valuation. This means that cryptocurrencies'

valuations are extremely volatile.

Despite the poor performance of cryptocurrencies

as means of exchange, unit of account and store of

value digital tokens such as Bitcoin, Bitcoin Cash,

Litecoin, Monero or ZCash behave as such. Poor

performance arises from three main factors, energy

consumption, scalability and lack of value stability.

However, historically technology has proven to

overcome most of its limitations which would present

lack of value stability as the main characteristic and

drawback of these subset of payment tokens. I

propose cryptocurrencies to be defined as simple

mediums of exchange, characterized by the absence

of (1) a legal right against a counterparty, lack of (2)

value stability and lack of (3) intrinsic value and

subject to (4) investment risk. Simply, I define a

cryptocurrency as a volatile payment token subject

to investment risk.

3.1.2 Subcategory of Stablecoins

A number "stablecoin" initiatives, backed by large

technology or financial firms and built on DLT

technology, are designed to address at least one of the

traditional payment system challenges: access to all

adult population to the payment system and cross-

border retail payments. An example of such

initiatives is Facebook’s Libra. Although private

DLT-based Tokens Classification towards Accounting Regulation

21

digital forms of money have been around for decades,

these new initiatives have access to large networks of

existing users and customers, which suggests that

they could be the first to have a truly global footprint.

Similarly to cryptocurrencies, these initiatives raise

formidable challenges across a broad range of policy

domains. Of particular concern are the risks related to

anti-money laundering and countering the financing

of terrorism, as well as consumer and data protection,

cyber resilience, fair competition and tax compliance.

Partly in response to these concerns, a working group

has been mandated by G7 finance ministers and

central bank governors to examine global

"stablecoins" in more detail.

If "stablecoins" become widely used, they could

also give rise to issues related to monetary policy

transmission and financial stability (Cœuré, 2019b).

Where a "stablecoin" acts as a substitute for fiat

currency, there may be the risk of the monetary

sovereignty of countries being infringed.

Furthermore, the transmission of monetary policy

could be affected if "stablecoin"-denominated credit

or overdraft extensions are provided. Finally,

financial stability will be affected if the assets

underlying "stablecoin" arrangements are not

managed in a sufficiently safe and prudent manner to

ensure that coin holders have confidence that their

coins are redeemable at par, in good times and in bad.

From a legal point of view, many but not all

stablecoins confer a contractual claim against the

issuer on the underlying assets (so-called redemption

claim) or confer direct ownership rights (FINMA, 16

February 2018). Value stability is granted as the token

is linked to currencies, to commodities, to real state

or to securities (FINMA, 16 February 2018).

Stablecoins linked to a single currency with a

fixed exchange rate (e.g. 1 token = 1€) classify as

payment tokens as they entitle no other legal right

than the redemption claims against the issuer.

stablecoins linked to a several currencies where there

is a redemption claim dependent on price

developments of the basket, classify as payment

tokens as long as all opportunities and risks from the

management of the underlying assets, (be they in the

form of profits or losses, from interest, fluctuations in

the value of financial instruments, counterparty or

operational risks), must be borne by the issuer of the

stablecoin (indicative of a bank deposit) and not the

holder (indicative of a collective investment scheme),

which classifies as security token.

Stablecoins are defined in this paper as tokens

with stable value, which may or may not have legal

rights against a counterparty. The absence of these

legal rights classifies the stablecoin as payment token,

whereas the existence of contractual claims classifies

the stablecoin as utility token or security token.

Payment Stablecoins characterize by the absence

of (1) a legal right against a counterparty, (2) value

stability, lack of (3) intrinsic value and lack of (4)

investment risk. Therefore we define stablecoins as

stable payment tokens not subject to investment

risk.

3.2 Utility Tokens (Digital Right)

A token can be created to define the value per unit of

service provided within a DLT platform. For

example, in a supply-chain management system, the

tokens can be assigned to be the value of the total

network divided by the total supply. It can also be

used to transfer data and amount ubiquitously across

the network. Hence, tracking, shipping details and

product details etc. can be recorded on the DLT

platform and updated continuously. They may act as

the internal network currency, which not necessarily

attempts to be a means of payment, it normally grants

owners the right to actively contribute to the system

(versus the passive investors’ role) and does not have

security features. These tokens can be compared to

API keys

used to access an online service. FINMA

defines utility tokens as they intend to provide digital

access to an application or service based on

blockchain. The purchase of a utility token gives a

user ability to gain access to an ecosystem. The

tokens, as API’s, may operate as service keys,

providing access to platforms infrastructure and main

functions. For example, when you buy an API key

from Amazon Web Services for dollars, you can

redeem that API key for time on Amazon’s cloud.

The purchase of a token like Ether (ETH) is similar,

in that you can redeem ETH for compute time on the

decentralized Ethereum compute network. This

redemption value gives tokens inherent utility

(Srinivasan, May 27, 2017). Specifically, tokens

either have a certain use case in the protocol (i.e.

Steemit’s token, Steem Dollar, used to stake in order

to be able to work for the network) or otherwise serve

as medium of exchange in the project’s ecosystem

(i.e. Powerledger’s POWR token used to buy and sell

energy on the platform). An example of a medium of

exchange token is casino chips which are used as

currency which can only be used to pay for gambling

at the casino. Store credit such as Sainsbury’s nectar

points is another example of a utility token which can

only be used to pay for goods at Sainsbury’s.

Moreover, these tokens are built-in transactional

value. Holders can transfer them to another party or

trade them on the appropriate token exchanges or

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

22

inside the system. This mechanism in its core helps

increase the whole value of the service and provides

tokens with potential market liquidity and inherent

utility. These types of tokens have been called utility

tokens.

Since a utility token represents utility or currency

in the protocol, token valuation must be based on the

supply and demand for that particular protocol.

However, this alone is not enough. Unlike an equity,

a token does not entitle its owner to any legal

ownership of the underlying protocol and the protocol

itself may not even generate cash flow. Macedo

(2018) suggest that utility token’s value depends on

the degree of correlation between demand for the

protocol and demand for the token itself. The token

value depends on its own demand and supply, which

may or may not be linked to the demand of the

protocol. As demand of the protocol increases, value

of the company increases and the value of the equity

increases. If demand of the platform and demand of

the token are correlated the value of the token

increases, if they are not correlated, the value will not

likely increase.

Two questions arise from the previous analysis:

(1) how investors capitalize the increase of the

company’s value, and (2) how this increase has no

relevant impact on the utility token volatility. The

two-fold approach suggests the existence of investors

and users, and consequently two different tokens.

Investors purchase tokens as means of funding the

platform and to obtain a return, while protocol users

purchase tokens to secure utility. Investor’s tokens

are different from user’s tokens. These tokens grant

different rights from utility tokens. They may provide

ownership, stream of cash flows, or other rights

similar to equity-like instruments. The tokens hold by

investors, which capture the increase of decrease in

the platform’s value are classified as security tokens

and the relationship structure between the value of the

ecosystem, the utility token and the security token is

the token economy.

Regulation therefore faces the challenge as to

determine whether a token is a security following

security-governing law or not. The Debevoise &

Plimpton report (December 5 2016) proposes an

analysis of the individual facts and circumstances of

each relevant token to appropriately determine

whether it would constitute a security and fall under

the securities laws or a utility token. They understand

that utility tokens entitle one or more of the following

rights: (1) to program, develop or create features for

the system or to ‘mine’ things that are embedded in

the system; (2) to access or license the system; (3) to

contribute labour or effort to the system; (4) to use the

system and its outputs; (5) to sell the products of the

system; and (6) to vote on additions to or deletions

from the system in terms of features and functionality.

Alternatively, we may draw the line between

security and utility tokens by means of the Howey

test. The test considers that an investment contract,

consequently a security, is ‘a contract, transaction or

scheme whereby [1] there is an investment of money;

[2] there is an expectation of profit; [3] in a common

enterprise; and [4] is led to expect profits solely from

the efforts of the promoter or a third party.’ Rohr and

Wright (2017) analyse the compliance of these four

conditions. While the first condition is likely fulfilled,

the other three are muddled. The distinction between

consumption and profit in utility tokens often

becomes complex. Although public may purchase

tokens due to its functionality and consumption

potential, the speculative potential most likely plays

also a role in purchasing decision. It might be unclear

a priori the intentions of purchasers as they might be

unsure whether they will consume the product or

service or trade the token in the exchanger. This will

depend whether the price exceeds the value of the

consumption. We may expect that a token can be

considered a security if the expectation of profit

dominates any expectation of consumption. In the

same context, the CNMV, the SEC and other

financial supervisors are aware of the difficulty of

defining and distinguishing utility tokens from

regulated securities. These institutions have

attempted to stablish certain regulatory framework.

The CNMV (February 8, 2018) considers that a large

part of the tokens should be treated as negotiable

securities.

‘As factors to assess if a token is considered a

security, the following are considered relevant:

A token would be considered a security if

attributes rights or expectations of participation

in the potential revaluation or profitability of

businesses or projects or, in general, that present

or grant rights equivalent or similar to those of

the shares, obligations or other financial

instruments.

A ‘functional’ token, that is granting access to

services or products, would be considered

security if carries an explicit or implicit

expectation for the purchaser to benefit from the

token revaluation, has any revenue associated or

recognizes its liquidity or possible trading in an

equivalent or similar market to the regulated

securities market.‘

The threefold approach suggests that developers

must first stablish the utility token functionality, and

DLT-based Tokens Classification towards Accounting Regulation

23

second the value of the token should not be linked to

speculation. Utility tokens should have a strong and

clear connection to some established form of value

(intrinsic value) to ensure price stability, thus provide

clearer basis to the project’s value. They should

behave as stablecoins. Functionality and traditional

anchors should become the link between the DLT-

based tokens and a widely recognized and established

form of value. Whilst the true usefulness (and

therefore ‘justifiable’ long term value) of a token

remains uncertain, these functionality aspects are

especially important. Utility token purchasers must

only intend to use the token on the functional level

limiting undesired speculative intentions. This ‘long-

term justifiable’ value of the utility token needs to be

detailed in the technical description and business

model of the Whitepaper.

On May 4, 2018, the Anguilla House of Assembly

enacted the Anguilla Utility Token Offering Act,

which provides for the first government approved

registration process for issuers of utility token

offerings. The Anguilla Utility Token Act or ‘AUTO

Act,’ is designed to facilitate clearly defined utility

tokens that do not have a feature of a security.

Firstly, a Utility Token is defined as any token

that (a) does not, directly or indirectly, provide the

holder(s), individually or collectively with other

holder(s), any of the following contractual or legal

rights (..) (b) has or will have in the future, upon

launch of the issuer’s Utility Token Platform, one or

more Utility Token Features.

Secondly, Utility Token Features means the

contractual right for a holder to utilize a token to –

(a) have access to, become a member of, or become a

user of a Utility Token Platform developed and

managed, or proposed in the issuer’s white paper to

be developed and managed, by the issuer,

(b) use as the sole or preferred (by economic

discount, preferred access, preferred use or

otherwise) purchase, lease or rental price for the

products and/or services provided or proposed to be

provided by or in the Utility Token Platform, or

(c) use as a means of voting on matters relating to the

governance, management or operation of the Utility

Token Platform developed and managed, or proposed

in the issuer’s white paper to be developed and

managed, by the issuer;

This four-approach analysis suggests that a token

classifies as utility token when following determinant

factors concur: (1) existence of legal right against a

counterparty, (2) token-value stability, (3) existence

of intrinsic value and (4) absence of investment risk.

A utility tokens is defined as a crypto-economic

unit of account with stable intrinsic value that

records or performs a specific function on a DLT

network, against legal counterparty, entailing no

investment risk.

3.3 Security Tokens

A security is a broad classification that refers to any

kind of tradable asset. Through initial offerings,

investors have access to a wide variety of security

tokens, ranging from coins redeemable for precious

metals to, tokens backed by real estate or equity-

based tokens. The latter show equity-like features,

such as decisions regarding the issue entity’s

dividends, ownership rights or profit shares. FINMA

defines such tokens are defined as ‘blockchain-based

units’ which represent ‘participations in real physical

underlying, companies, or earnings streams, or an

entitlement to dividends or interest payments’ and are

‘standardized and suitable for mass standardized

trading‘.

Following FINMA guidelines (11 September

2019), depending on the specific purpose and

characteristics of the underlying right or asset, the

token will classify as utility or security. First, where

the underlying assets are a basket of currencies which

are managed for the account and risk of the token

holder (indicative of a collective investment scheme)

or for the account and risk of the issuer (indicative of

a deposit under banking law). For the former

categorization to apply, all opportunities and risks

from the management of the underlying assets, be

they in the form of profits or losses, from interest,

fluctuations in the value of financial instruments,

counterparty or operational risks, must be borne by

the holder of the token, the token classifies as

security. Second, where a token is linked to

commodities, the exact nature of the claim on the

assets as well as the type of commodity (in particular

whether "bank precious metals" or other commodities

are involved) are of particular significance. Where the

token merely evidences an ownership right of the

token holder, it generally does not qualify as a

security. However, where there is a contractual claim

on other commodities, the token will generally

qualify as a security and possibly as a derivative.

Third, where the underlying assets are individual

properties or a real estate portfolio, the normal third-

party management of the real estate portfolio is in

itself an indication of a collective investment scheme.

Finally, a token that is linked to an individual security

by way of a contractual right for delivery to the token

holder would normally also constitute a security.

In the US, tokens would classify as securities

when complying with the first requirement of the

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

24

Howey test. In order for a financial instrument to be

classified a security and fall under the purview of the

SEC, the instrument must meet these four criteria:

whereby [1] there is an investment of money; [2]

there is an expectation of profit; [3] in a common

enterprise; and [4] is led to expect profits solely from

the efforts of the promoter or a third party.’ That

former condition is most relevant. The key criteria to

classify a token as relates to whether the token-holder

may affect the existence of a profit or loss. Purchasers

of tokens should be perceived as investors and the

issuance of tokens as equity or liability for the

company. Investors have an expectation of profit in a

common enterprise and they are led to expect profits

solely from the efforts of the issuer or a third party.

The European Securities and Markets Authority

(ESMA), a European Union (EU) financial regulatory

body and European Supervisory Authority located in

Paris, issued in November 2017 a Statement on Initial

Coin Offerings (ICOs), on the rules applicable to

firms involved in ICOs. In this Statement, ESMA

reminds firms involved in STOs of their obligations

under EU regulations. The Statement informs that if

‘…tokens qualify as financial instruments it is likely

that the firms involved in initial offerings conduct

regulated investment activities, such as placing,

dealing in or advising on financial instruments or

managing or marketing collective investment

schemes. Moreover, they may be involved in offering

transferable securities to the public. The key EU rules

listed below are then likely to apply’.

According to the financial market Spanish

regulator (CNMV) a token should be considered a

security: ‘(1) whenever the ‘tokens’ provide rights or

expectations of participation in the potential

business/projects revaluation or profitability or,

whenever, they present or grant rights equivalent or

similar to those of the shares, obligations or other

financial instruments included in the article 2 of the

TRLMV (2) whenever the tokens grant the purchaser

the right to access services or receive goods or

products, which are offered by referring, explicitly or

implicitly, to the expectation of obtaining by the

buyer or investor a benefit as a result of its revaluation

or any remuneration associated with the instrument or

mentioning its liquidity or possibility of trading in

equivalent or similar markets to the securities markets

subject to the regulation’.

The new generation of tokens can provide an

array of financial rights to an investor such as equity,

dividends, profit share rights, voting rights or buy-

back rights. Often these tokens represent a right to an

underlying asset such as a pool of real estate, cash

flow, or holdings in another fund. The main

difference to traditional securities lies in the fact that

these rights are written into a SC and the tokens are

traded on a blockchain-powered exchange.

A relevant feature of security tokens is its higher

dependence on the speculative value. Previous

sections have explained that value of DLT-based

tokens depends on the intrinsic and the speculative

value. Equity-like tokens incorporate higher

speculative value as the purpose of the token is to

capture variation of value for investors return. Token

economic models combine function-based tokens

(utility tokens) and equity-like tokens (security

tokens) as for the former to provide price stability for

the network user, and the later to allow price volatility

for the investor.

Previous analysis suggests security token to be

defined as a crypto-unit of account on a DLT

platform with legal counterparty, intrinsic value

and speculative value which incorporate risk in

the expected cash flows associated with the token

as it is being held.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Over the last few years, the prevalence of digital

currencies has increased. However, the emergence of

the token-economy and the DLT-based tokens as

disruptive elements of business models, have

evidenced the urgent need to define, classify and

regulate these digital tokens, which cove more than

digital currencies. In this paper we provide initial

guidance to define, classify and regulate digital

tokens within the accounting sphere. Voices have

raised urging to clearly distinguish the different

natures and functionalities of crypto-assets. Not all

tokens issued from a distributed ledger technology

(DLT) are to be considered similarly. Julio Faura (8

Feb 2018), head of the blockchain development at

Banco Santander urged ‘... that it would be a good

idea to clearly separate functionality from funding.

Mixing those together ends up producing transaction

costs that are artificially high, since access to

functionality is subject to speculation. I always

understood the role of ether as a mechanism to pay

for the use of a network that implements a shared

supercomputer, which is a truly amazing construct

that can change the world for good. But its dual role

as an access token and a currency to store value is

making the construct expensive and difficult to use in

practice ‘.

Following the FINMA classification scheme, this

paper provides a systematic and clear guidance to

classify tokens into payment tokens (with the

DLT-based Tokens Classification towards Accounting Regulation

25

subcategories of cryptocurrenies and stablecoins),

utility tokens and security tokens as to reduce

uncertainty on the financial and accounting

regulatory framework. The previous analysis

suggests four factors as basic criteria to classify the

DLT-based tokens: (1) the existence of a legal right

against a counterparty; (2) the existence of token-

value stability; (3) the existence of intrinsic value;

and (4) the existence of investment risk.

First, the lack of any legal right against a counterparty

and the lack of intrinsic value classifies a token as a

payment token, which solely serves as store of value

and as a means of payment. Where payment tokens

present value volatility and investment risk they

classify as the subcategory of cryptocurrencies.

Where payment tokens present value stability and

non-investment risk, classify as the subcategory of

stablecoins. Second, utility tokens provide a legal

right for the holder against the DLT-network issuer,

deliver value stability and intrinsic value. The

intrinsic value arises from the functional nature of

these tokens which are created to capture and

exchange value across a DLT-based ecosystem.

Value stability is key to allow the functionality treat

to dominate any speculative incentives to profit from

exchanger trading. Finally, security tokens present

legal rights against a counterparty and intrinsic value

which stems from the right, obligation or asset linked

to the crypto-token. Unlike utility tokens, these

security-like tokens lack price stability and the

speculative value of the token competes with its

functional intrinsic value. This suggests the presence

of underlying expectations on gains which classifies

the token as a security. These DLT-based tokens

might have equity-like qualities, they might represent

a liability or an asset, which could resemble

traditional regulated securities. However, DLT-based

tokens might be utility-like tokens, for example,

tokens providing access to future consumption of

goods or services, that fail to comply with conditions

(2) existence of value stability or (4) absence of

investment risk. Regulators need to acknowledge that

underlying nature of the token is not sufficient

condition to classify as utility, the existence of

investment risk invalidates this classification and

requires the token to follow the financial regulations.

Consequently, utility-structured tokens may also

qualify as securities thus the definition of security

token becomes complex due to the broad scope of

their nature. Future research is required to better

understand the heterogeneous characteristics of

security tokens.

REFERENCES

Bashir, I. (2018). Mastering Blockchain. UK: Packt

Publishing Ltd.

Beck, R., Stenum Czepluch, J., Lollike, N., & Malone, S.

(2016). Blockchain- the getaway to trust-free

cryptographic transactions. Research Papers. 153. doi:

htt://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2016_rp/153

BIS. (2018). Cryptocurrencies: looking beyond the hype.

Bank for International Settlements Annual Economic

Report. https://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2018e5.htm

Bordo, M., & Levin, A. (2017). Central Bank Digital

Currency and the Future of Monetary Policy. National

Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved from

https://www.nber.org/papers/w23711.pdf

Brooks, S., Jurisevic, A., Spain, M., & Warwick, K. (2018).

A decentralised payment network and stablecoin.

Haven.

Catalini, C., & Gans, J. (2016). Some Simple Economics of

the Blockchain. NBER Working Paper No. 22952. doi:

https://ssrn.com/abstract=2874598

CNMV. (February 8, 2018). Considerations of the CNMV

on "cryptocurrencies" and "ICOs" directed.

Debevoise & Plimpton. (December 5, 2016). Securities

Law Analysis of Blockchain Tokens.

Ehrsam, F. (2017, November 17). Blockchain Governance:

Programming our Future. Medium.

Financial Stability Board (FSB). (10 October 2018).

Crypto-asset markets. Potential channels for future

financial stability implications.

FINMA, S. F. (11 September 2019). Supplement to the

guidelines for enquiries regarding the regulatory

framework for initial coin offerings (ICOs).

FINMA, S. F. (16 February 2018). Guidelines for enquiries

regarding the regulatory framework for initial coin

offerings (ICO).

Forbes. (2019, Jan 24). How Much Time Americans Spend

In Front Of Screens Will Terrify You. Forbes.

Klaus, I. (2017). Don and Alex Tapscott: Blockchain

Revolution. New Global Studies, 11(1), 47-53.

Lemieux, V. L. (2016). Trusting records: is Blockchain

technology the answer? Records Management Journal,

26(2), 110-139.

MME Legal|Tax|. (2018). Conceptual Framework for Legal

and Risk Assessment of Crypto Tokens.

Pilkington, M. (2016). Blockchain Technology: Principles

and Applications. (i. F. M., Ed.) Research Handbook on

Digital Transformations, Edward Elgar.

FEMIB 2020 - 2nd International Conference on Finance, Economics, Management and IT Business

26