Challenges and Opportunities for Caregiving through Information

and Communication Technology

Jane Moloney

1

, Raja Manzar Abbas

2

, Sarah Beecham

2

, Bilal Ahmad

2

and Ita Richardson

2

1

Department of Computer Science and Information Systems, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

2

Lero, the Irish Software Research Centre, University of Limerick, Ireland

Keywords: Caregivers, Technology, Qualitative Study, Older Adult Care, Monitoring, Prototype.

Abstract: The increased susceptibility of world’s population to diseases augmented with the decrease in the healthcare

workforce leads to over-reliance on caregivers. This increased burden on caregivers adversely impacts their

quality of life. However, information and communication technology (ICT) has the potential to facilitate

caregiving. Therefore, the objective of this study is to investigate the opportunities and challenges for

caregiving through ICT, the development of a prototype to support caregivers better monitor their care

recipients (known as clients) and the evaluation of that prototype. A qualitative study with 10 caregivers was

conducted to address the research questions from which data was coded and analysed. Using this data, a web-

based prototype was developed and evaluated by 5 caregivers and 5 technology experts. The instruments used

were interviews and focus groups. The results revealed eight categories for improving care identified by

caregivers.

1 INTRODUCTION

The world’s population is becoming more susceptible

to disease and disability, high birth rates with lower

mortality rates, the prospective workforce not

choosing healthcare as a profession and the shortage

of supported facilities. In Ireland, healthcare staffing

levels have dropped significantly within the public

sector since 2009 (Wells and White, 2014). This

situation leads to over-reliance on family or

professional caregivers, which adversely impacts

their quality of life (Canam et al., 1999, Osse et al.,

2006, Shiue et al., 2016), and it is noted that some of

the problems that caregivers encounter include

anxiety, depression and stress (Koyanagi et al., 2018,

Washington et al., 2018). Information and

Communication Technology (ICT) has the potential

to alleviate these problems and help caregivers

perform their duties efficiently and effectively

(Finkel et al., 2007, Chi et al., 2015, Czaja et al., 2016,

Demers et al., 2018). A recent systematic literature

review provides an in-depth analysis on the type of

ICT offerings in this context such as education,

consultation, behavioural therapy, social support,

data collection and monitoring and clinical care

delivery (Chi et al., 2015). This work also reveals that

only 20% of the technology developed falls under the

domain of monitoring, so further work is needed on

this topic. Our analysis indicates that only 2 tools

mentioned in research studies (Chou et al., 2012;

Shah et al., 2013) help in care management while also

solving other problems of caregivers such as social

isolation and quality of life. But, caregivers cited

problems with the design, reliability, weight, and size

of the equipment as serious challenges, decreasing

their satisfaction and increasing their frustration. A

literature review by some of this paper’s authors also

highlights problems with the technology which is

available to support the social life and healthcare of

patients such as older adults (Ahmad et al., 2017).

This situation advocates the need to continue research

in this area and explore the challenges and

opportunities for caregiving through ICT before

commencing the development of systems. The

objective of this study is to understand how ICT

monitoring in the home can alleviate the burden on

the caregivers, and provide a better quality of life

(QOL) for both stakeholders (caregivers and care

recipients). Care recipients are often older adults.

The nomenclature used by caregivers during

interviews when discussing care recipients is ‘client’,

and so, for consistency in this paper, we will refer to

care recipients as ‘clients’. An analysis of the

literature and a qualitative study of a small sample of

Moloney, J., Abbas, R., Beecham, S., Ahmad, B. and Richardson, I.

Challenges and Opportunities for Caregiving through Information and Communication Technology.

DOI: 10.5220/0008893603290336

In Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC 2020) - Volume 5: HEALTHINF, pages 329-336

ISBN: 978-989-758-398-8; ISSN: 2184-4305

Copyright

c

2022 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

329

stakeholders, led to the development and evaluation

of a web-based prototype for an optimized home

based monitoring system for caregivers.

Section 2 describes the methodology used during

this research. Section 3 discusses the outcome from

caregiver interviews. Section 4 describes how the

findings of interviews were used to develop the

prototype. Section 5 presents the evaluation of the

prototype using focus groups. Section 6 concludes the

paper, presents the recommendations and outlines

future work.

2 METHODOLOGY

The objective of this study is to address the following

research questions:

1. Can ICT support the monitoring of clients in the

home for improved caregiving efficiency?

2. Could the provision of ICT monitoring reduce

burden of the caregiver and improve QOL of the

client?

To answer these research questions, we undertook

a qualitative study with clients and caregivers. Based

on this study, we developed a prototype device using

proprietary product, aimed at monitoring clients in

the home.

2.1 Data Collection: Interviews

We conducted semi-structured interviews over a 2-

day period, with a purposive sample of 10 caregivers

of clients (mainly older adults), based in Ireland (see

Lero Technical Report 2020-TR-01 for the interview

protocol). The primary objective was to identify the

difficulties associated with caregiving to clients and

how ICT might reduce some of the challenges for

caregivers. Using 14 questions, also available in

2020-TR-01, derived from related literature, we

uncovered a set of requirements. The average

duration of each interview was 30 minutes and was

audio recorded. We developed and evaluated a

prototype.

2.2 Data Collection: Focus Groups

To carry out the evaluation, we undertook a focus

group (see protocol in 2020-TR-01). This allowed us

to gain feedback on the prototype and to identify

features for future refinement. One 90-minute session

was held with a mix of participants – 5 caregivers and

5 technology experts. The key requirement for

technology experts was to involve researchers and/or

developers who are directly linked with homecare

technology development. All caregivers who

participated in the focus group had been involved in

the group of interviewees.

2.3 Data Analysis

Audio recordings of the interviews and focus groups

were transcribed, and were analysed using descriptive

coding (Saldana, 2015) to determine key topics. This

was achieved through labelling the important

concepts in the transcripts. These labels were

scrutinized against the research questions to gain

further context of the labels. Furthermore, memoing

and commenting was done liberally. Descriptive

coding was used as an input to perform pattern

coding, determining the high level concepts and the

relationships between them. Finally, axial coding was

undertaken which helped to gain a deeper

understanding of categories.

3 IMPROVING CARE

In this section, we outline our answer to Research

Question 1: Can ICT support the monitoring of clients

in the home for improved caregiving efficiency?

Interview analysis using descriptive and pattern

coding resulted in the identification of eight

categories.

1. Technology for Monitoring: A major concern

amongst all the caregivers was the lack of monitoring

of their clients. Eighty per cent of participants were

either family care or voluntary care persons who did

not earn a financial salary from the care they

provided. Therefore, they need to remain in full time

employment, meaning that they could not monitor

clients for large amounts of time. This same 80%

were concerned with external factors such as

temperature changes across seasons as, regardless of

whether a source of heating or cooling patients’

homes was available, some patients do not avail of

these methods. An extreme example is that one

patient did not use the heating for a few days,

ultimately causing hyperthermia. Temperature

monitoring would have averted this.

2. Technology to improve Safety: Caregivers were

worried about the safety of their clients and

highlighted the need for purpose built housing; clients

are at a vulnerable stage in their lives and likelihood

of injury is very high. One participant quoted that it is

becoming increasingly difficult for their client to

reach the first floor of their home where their main

sleeping quarters are located. Dangers include clients

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

330

falling down the stairs and nobody knowing for a few

hours until a neighbour visited. Real-time monitoring

technology has the potential to provide a safer

environment.

3. Technology for Security: Participants stated that

clients face serious security issues such as strangers

calling to the doors of clients leading to burglary,

assault or confidence tricks, with all participants

reporting security-related events. One particular

example was when strangers attempted to convince

their client to pay a sum of money. Being

unsuccessful, they assaulted the person. Participants

suggested that there is a need for a technology which

can provide instant alerts to caregivers or emergency

services. They also shed light on clients’ lack of

familiarity with current technology such as

smartphones, indicating that technology should be

designed in an easy to use and intuitive fashion.

4. Technology to Support Emergencies:

Participants advocated the need for a ‘single action

alert’ or a ‘voice-activated alert’ to alleviate the

difficulty vulnerable people face while reporting

emergency situations using technology such as

smartphones. They also said that clients are not well

versed with the latest technology and some are living

without mobile phones and Internet, so alternative

mechanisms to report emergencies would be

appreciated and could be more easily adopted by their

clients.

5. Resources: A lack of resources was identified, for

example, where multiple clients are co-habiting, as in

the case of spouses. One participant quoted that their

deaf client had to take care of a blind person. It is

obvious from this how much support these clients can

provide to each other, and that any technological

solution which improves this situation would be

welcomed.

6. Primary Care: A positive outcome was ease of

access to general practitioners through appointments,

but transportation was still troublesome, e.g. “While

the request is relatively simple to submit and it only

takes 24 hours to get approval, it is still the difference

of 30 minutes to 24 hours in the case of something

that may be more of a serious case than first thought”

- Participant C4. This delay in primary care

concerned the participant who understood that

insurance implications needed to be adhered to as

well.

7. Assistive Technology: Participants agreed that

assistive technology would be beneficial for

providing homecare. Forty per cent of the participants

revealed that significant injury had happened to their

clients during the provision of care. An advance could

be to have lifting technology (operated via a computer

user interface) to reduce injuries.

8. Processing of Requests: The government is

providing lifting technology to eligible clients but the

processing time is extremely slow. One participant

said: “It should not have taken that long to receive a

chair I could have purchased online and received in

a fraction of the time for my mother to have basic

comfort in her own home” - Participant C9. It was

clear from participants’ reviews that the request

submission process should be changed.

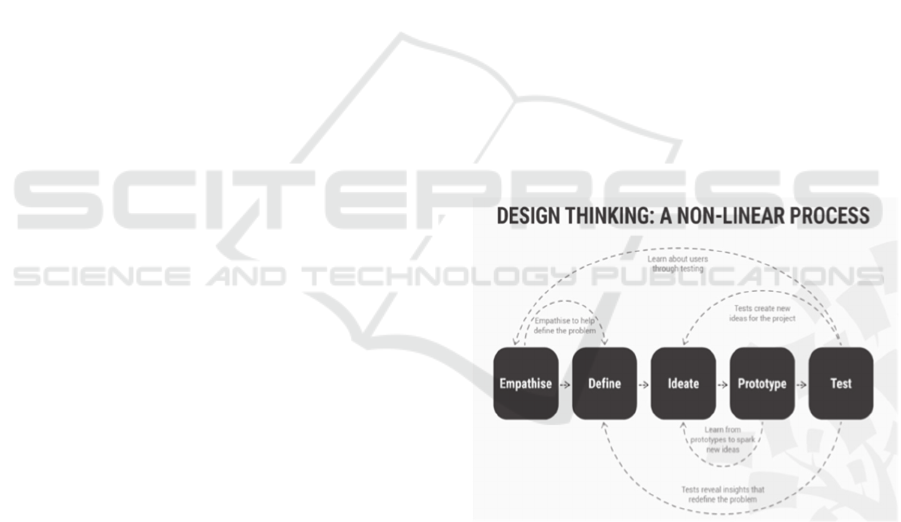

4 PROTOTYPE DEVELOPMENT

Based on our interview analysis, a prototype was

developed using design thinking (Siang, T. 2019), see

Figure 1. Prototyping an application is crucial in

helping participants understand the key aspects of a

proposed system are and allows them to interact with

features as if it were a real-life system. Design

thinking was used as it helps to strip away non-

essential aspects of the problem situation. Within

design thinking, there are 5 stages – empathize,

define, ideate, prototype and test. In this project, we

undertook the first 4 stages.

Figure 1: Design Thinking Process (Siang, T. 2019).

4.1 Empathize

The interview data was reviewed to understand the

caregiver’s feelings, needs, and problems and pain

points. A spectrum of feelings and the associated

behaviours of all of the participants were extracted

through the review of interview data as indicated in

Table 1 in Lero Technical Report No: 2020-TR-01.

These include anxiety, guilt and regret and they were

observed amongst all participants at some stage

during the interviews. Particularly harrowing was the

Challenges and Opportunities for Caregiving through Information and Communication Technology

331

guilt and anger, which were two common feelings

portrayed. One participant spoke of the decision to

put their client into a professional care home due to

the lack of availability of help, time and facilities

when the client was cared for at home. Such

information was used in prototype design.

4.2 Define

After understanding caregivers’ feelings and

behaviours, they were translated into point of views

(POV), which constitutes of three measures i.e. User,

Need and Insight. Table 2 (in Lero Technical Report

No: 2020-TR-01) presents the complete point of view

analysis table. These user needs and insights were

then used to generate ‘How Might We’ (HMW)

questions. The POV table and the HMW questions

were later used as an input to brainstorm and define

the problem statement:

“Design and develop a product that aids family

carers who care for clients in the clients’ own home.

This should enable a more stable life balance maybe

only requiring touch points with client, to a full care

suite. This should encompass features that allow

monitoring, safety in the home, security features and

alert features”.

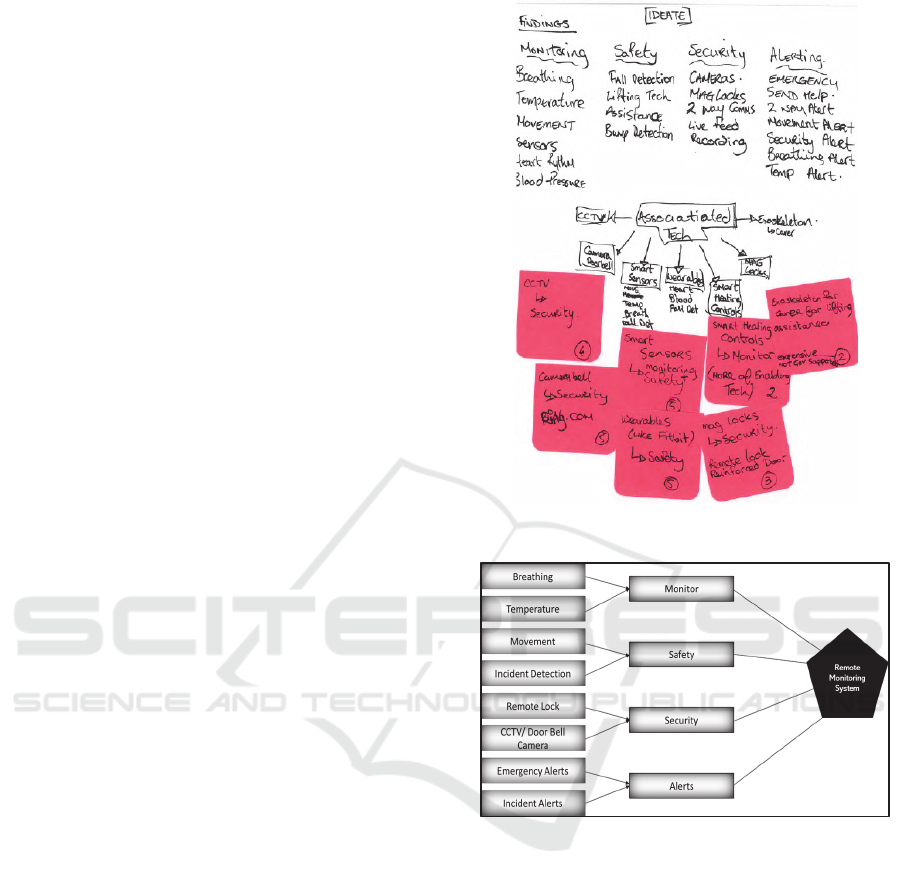

4.3 Ideate

Ideation was the third phase and it constituted of

brainstorming by the researcher to generate numerous

ideas by broadly exploring the solution space to

determine the best outcome. Typically, this phase

requires a team, but due to time constraints, the first

author completed this activity and later validated the

results using a focus group. Mind mapping was used

as an aid during this phase, ultimately inputting to the

development of the prototype. The raw outcome of

the ideation phase in shown in Figure 2 and the model

is depicted in Figure 3. This model applies technology

to homecare situation to see the positive effects on the

client. Based on the findings, the main aspects of the

model and the resulting system should include

monitoring of the clients’ breathing and temperature,

ensuring the safety of the client and incident

detection, the security of the client and enabling alerts

to the caregiver with specific consideration to

emergency alerts.

Figure 2: Ideating Phase Outcome.

Figure 3: Model for Remote Monitoring System.

4.4 Prototype

The model was used as the basis for prototype

development. The underlying assumptions during the

development of prototype were that some ambient

living solutions were available. The clients’ home

has been fitted with detection sensors and cameras

and a doorbell with a camera and 2-way intercom on

the exterior. Motion and temperature sensors, smart

thermostats and intelligent heating controls have been

fitted inside. Clients have been given a smart watch

to monitor vitals and to increase accuracy on fall

detection.

While we recognise that this set of systems is

complicated in themselves, they are each readily

available commercially, and the requirement from the

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

332

caregiver focuses on the ability to monitor clients’

activities. A sitemap of the prototype was developed

(available in the technical report), with each branch

having its own individual dashboard. An example of

one high level dashboard is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Remote Monitoring System - Client Dashboard.

5 PROTOTYPE EVALUATION

To answer Research Question 2: Could the provision

of ICT monitoring reduce burden of the caregiver and

improve QOL of the client?, the prototype was

evaluated through a focus group with caregivers and

technology experts. By following the guidelines by

Jankowicz (1995), the researcher remained cognitive

and provided appropriate interjections to keep the

discussion focused, probing deeper into the topic to

encourage participants to express their views in

detail, thus enriching the data. Eight key items were

identified, and are discussed here under the headings

of features and usability.

5.1 Features

Overall, the participants liked the features of fall

detection, body temperature and access to

surveillance remotely from a mobile device. For

example, a participant highlighted the importance of

this prototype system in general: “I had an incident

where my client had fallen down the stairs and had

not been found until the following morning. With this

the response is almost immediate meaning my client

will never have to experience that again” - Caregiver

C1.

5.1.1 Dashboard

Participants were pleased with the simple navigation

through the slide-out menu allowing them to switch

between dashboards quickly and easily. “This menu

displays basic information of the client for

identification and reassurance. Having the option to

view the profile from my client for further information

such as medical history, personal details makes it

easier for me to relay medical history and

information on our GP Visits” – Caregiver C5.

All of the participants agreed on the need for a

feature ensuring that, if they do have an incident, their

client is found and treated within a short period of

time. They also appreciated the clean and easy to use

interface and navigation, but shared a concern of

additional Wi-Fi data charges, as the application

constantly refreshes itself: “Is this not supposed to

help carers regain a balance? Their wallet will be

heavily affected if they have more than eight to ten

clients on the system at each time, data is expensive

outside a set price plan” - Caregiver C3

5.1.2 Alerts

Participants liked the idea of alerts, and shared the

possibility of having additional alerts including

delivery tracking, power outage alert and an increased

audio sensitivity: “There is potential to have more

various on the alerts, while I understand this is just

phase one of the application, it has infinite

possibilities to adapt features to service many other

medical situations” – Technology Expert T1.

Participants were satisfied that the alerts are

automatically assessed by the system to determine the

urgency of each detection for quick analysis by the

user: “This is so beneficial for us to decide whether

the level of care and how urgently we need the client

to be treated after the incident. This could become

and invaluable feature for a lot of work we do, it

allows us to rely on our judgement more”- Caregiver

C3. Moreover, they were pleased with the ability to

get rid of ‘clutter’ and show only the necessary

information: “It’s great that I can pick and choose

what I want to display on dashboard of each of my

clients, there are some things I don’t need to see and

may become cluttered and confusing” - Caregiver C1.

The option to call first responders, emergency

services and family members really impressed all of

the participants: “It is great to see that we are starting

to see the utilization of the rural first responder as

first point of contact before emergency services are

needed. There are certain situations that a first

responder can deal with without having to call

emergency services. It causes extreme anxiety and

stress to care recipients having ambulances arrive to

the home when they are possibly not needed in some

cases” - Caregiver C4.

Challenges and Opportunities for Caregiving through Information and Communication Technology

333

5.1.3 Security

Caregivers were particularly overwhelmed and

grateful because their clients’ stories received distinct

attention during the prototype development and

features were included to ensure their security. They

certainly believe that the security feature will make

difference in their clients’ life: “This security tab

would have certainly made noticeable difference …

Besides providing a solid opportunity to catch the

culprit but it would have offered my client a sense of

feeling safe in their home. Unfortunately, my client

fears being home now alone, so I think this feature

will make a major difference to my client’s quality of

life.”- Caregiver C1.

Technologists, however, pointed out that the

current sensors might provide unnecessary alerts to

the care providers. But, using less sensitive sensors

can alleviate this: “These sensors are so sensitive they

would pick up a leaf in the wind, this may cause

unnecessary alerts to the carer that would revert to

them being on edge more than they are now. The

doorbell-activated camera would be best to detect

people coming to the front door. I think standard

surveillance for the exterior home would be fit for

purpose here” - Technologist T2.

5.1.4 Safety

The safety tab offers real time information based on

incident detection and movement in the home. The

beneficial feature that was highlighted here was that

incidents are automatically analysed by the system

based on urgency. Non-urgent detections are sent to

the alerts tab but do not notify the user. In the

prototype, falls are considered major and then

notification is sent to the caregiver immediately:

“This is a great feature, you can tell if the client is

constantly bumping into something because they may

have forgotten the item is there and it will need to be

moved from the area to mitigate any other incidents

from happening. I know my client’s family bought

them a new chair and the client kept bumping into it

because it was not part of their home originally. It

eventually ended in removing the item because from

consistently bumping the same area repeatedly and

caused a fracture for the client” – Caregiver C2

5.1.5 Monitoring

The monitoring tab highlights the client’s vital data in

real time. This was well accepted by participants,

highlighting that certain clients might be at high-risk

status for pulmonary problems, needing constant and

consistent monitoring. “This is of particular benefit

to my client as the client has an irregular heartbeat

that constantly has to be monitored but this is

extremely difficult for me to do when I have to

maintain my full-time job at the same time. If the

client has an episode, I don’t want it to be my fault

because I was unable to monitor the client closely” -

Caregiver C5.

Technologists were a little bit concerned about the

type of technology that is going to be used to gather

this vital information: “I know this system is still in

its infancy, but I would have concern regarding the

technology you have decided to collect that data with.

There is a fear that the client may not wear the watch

or take it off while an event is occurring. This would

raise a major concern for me, but I am sure there are

better technologies for gathering this information” -

Technologist T4.

5.2 Usability

5.2.1 Aesthetic and Minimalistic Design

Participants complimented the overall design of the

application as it follows the current trend of sleek, flat

minimal design that can easily be familiar for the

user. The participants commented that this makes

analysing information much clearer and easier to

understand, preventing possible errors: “The design

is very attractive, and it has the added bonus that you

don’t need to be a data analyst to understand the

output information and can help carer’s make a

decision to the urgency of the incident at hand and

deal with it remotely” – Technologist T3

This design helps to keep everything organized. It

also notifies the caregiver about the most important

information. It has the potential to alleviate

distractions and ease the decision-making process.

5.2.2 Flexibility and Efficiency of Use

The caregiver can fully customize the user interface

to suit their needs while prioritising information

based on their clients’ needs. The application gives

the caregiver insights rather than having to search for

the information they need. The application is flexible

where icons, tabs and menu panels can be rearranged.

“It’s great how simple it is to use without prior

training. I can move and rearrange items with ease.

This is incredible as I have used other software that

it complicated and I eventually stopped interacting

with it. I actually want to interact with this

application” - Caregiver C2.

One technologist mentioned that a system like this

would help improve the caregiver’s efficiency. The

prototype stays consistent using the side bar menu,

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

334

which is accessible on every page, and it follows

standard user interface layouts. The opening

dashboard gives full system visibility with quick

information from all possible features.

5.2.3 Probability and Feasibility

Technologist T1’s statement - “Communication

between devices and public service systems is key for

this to succeed, reliance on Wi-Fi connections is a

concern as rural internet infrastructure is not as

developed as urban areas, the introduction of 5G in

the future could contribute to the rural infrastructure

but that is yet to be tested” - generated rich

conversations around infrastructure in Ireland and

whether it will be developed to accept our proposed

solution. The researcher clarified that this research

assumes that the infrastructure is ready. Another

important aspect that was noted was that General

Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) would have a

significant effect on this system and how it is

implemented if it ever became a viable solution.

Security concerns regarding CCTV and live data

would need to be examined thoroughly and cyber

security would need strong protection from system

hackers. As stated by technologist T4: “You would

need to introduce a strong standard around signing

and maintaining consent forms, there would be

significant churn in the public eye around this issue

and vulnerable persons, it may not be held in the best

light”. The participants felt that it was a very feasible

system assuming that all approvals were obtained,

and that privacy was maintained throughout the

development of the system. The prototype sets out to

apply advanced technologies to support home care

providers in their caring roles. Ninety per cent of the

participants felt that it met the goals it set out to do

and feel that if it were ever to be a commercialised

product that was affordable the caregivers would not

hesitate to install it in their clients’ homes.

In short, participants were pleased with the

features and the usability of the proposed application

and gave some useful recommendations for future

work. They mentioned that the fully functional

application would have the potential to give them

back their life balance, allowing them to be free to

work full time and maintain involvement in

recreational activities. Most importantly, it would

support the dignity of their clients.

6 CONCLUSION

This research focused on applying ICT to the home

care sector with a view to optimising the work of

family caregivers. The application of such

technologies was theoretically intended to allow such

caregivers to re-establish or to maintain their life-

balance. It could also support private caregivers to

split their time between several clients. The findings

suggest an overall positive response by the

participants about the prototype developed and its

potential to be commercialized. Some

recommendations were recognised as possibilities for

further development of the application:

System and technologies must grow at the same

pace as other technologies grow and develop.

24/7 customer support will be needed in case of

errors and system crashes.

The system could predict incidents through

gathering information for the implementation of

artificial intelligence (AI) to predict incidents.

Better monitoring technology or other forms of

monitoring technology should be utilised.

Improved user interface aesthetics helps to build

a positive relationship, workflow and interaction

of the caregiver.

Remote locking of front and back doors could be

included in the application.

Other safety measures could be implemented,

such as slip detection, recognition of

overheating, and vital sign measurement.

Our future work, particularly through our

membership of the Ageing Research Centre and our

industry links within Lero – the Irish Software

Research Centre, will investigate further how such

technologies can support caregivers in their vital job

of caring for older persons, while also providing

effective care to the client.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported, in part, by Science

Foundation Ireland grant no. 13/RC/2094. It was

carried out in partial fulfilment of the MSc in

Technology Management at the University of

Limerick (Atlantic University Alliance Ireland) and

the research ethics number is Ref.2019_07_04_S&E.

Challenges and Opportunities for Caregiving through Information and Communication Technology

335

REFERENCES

Ahmad, B., Richardson, I. and Beecham, S., 2017,

November. A Systematic Literature Review of Social

Network Systems for Older Adults. In International

Conference on Product-Focused Software Process

Improvement (pp. 482-496). Springer, Cham.

Ahmad, B., Richardson, I., McLoughlin, S. and Beecham,

S., 2018, July. Assessing the level of adoption of a

social network system for older adults. In Proceedings

of the 32nd International BCS Human Computer

Interaction Conference (p. 225). BCS Learning &

Development Ltd.

Britto, M.T., Jimison, H.B., Munafo, J.K., Wissman, J.,

Rogers, M.L. and Hersh, W., 2009. Usability testing

finds problems for novice users of pediatric portals.

Journal of the American Medical Informatics

Association, 16(5), pp.660-66.

Byczkowski, T.L., Munafo, J.K. and Britto, M.T., 2014.

Family perceptions of the usability and value of chronic

disease web-based patient portals. Health informatics

journal, 20(2), pp.151-162.

Canam, C. and Acorn, S., 1999. Quality of life for family

caregivers of people with chronic health problems.

Rehabilitation Nursing, 24(5), pp.192 200.

Chi, N.C. and Demiris, G., 2015. A systematic review of

telehealth tools and interventions to support family

caregivers. Journal of telemedicine and telecare, 21(1),

pp.37-44.

Chou, H.K., Yan, S.H., Lin, I.C., Tsai, M.T., Chen C.C. and

Woung, L.C., 2012. A pilot study of the telecare

medical support system as an intervention in dementia

care: the views and experiences of primary caregivers.

Journal of Nursing Research, 20(3), pp.169-180.

Czaja, S.J., 2016. Long-term care services and support

systems for older adults: The role of technology.

American Psychologist, 71(4), p.294.

Demers, L., Fast, J., Mortenson, W.B., Routhier, F., Auger,

C., Ahmed, S., Boger, J., Rudzicz, F., Plante M. and

Eales, J., 2018. Developing innovative interdisciplinary

technological solutions for caregivers of older adults

within Canada's technology and aging network. Annals

of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 61, p.e409.

Finkel, S., Czaja, S.J., Martinovich, Z., Harris, C., Pezzuto,

D. and Schulz, R., 2007. E-care: a telecommunications

technology intervention for family caregivers of

dementia patients. The American journal of geriatric

psychiatry, 15(5), pp.443-448.

Maher, M., Kaziunas, E., Ackerman, M., Derry, H.,

Forringer, R., Miller, K., O'Reilly, D., An, L.C.,

Tewari, M., Hanauer, D.A. and Choi, S.W., 2016. User-

centered design groups to engage patients and

caregivers with a personalized health information

technology tool. Biology of Blood and Marrow

Transplantation, 22(2), pp.349-358.

Osse, B.H., Vernooij-Dassen, M.J., Schadé, E. and Grol,

R.P., 2006. Problems experienced by the informal

caregivers of cancer patients and their needs for

support. Cancer nursing, 29(5), pp.378-388.

Saldana, J., 2015. The coding manual for qualitative

researchers. Sage.

Shah, M.N., Morris, D., Jones, C.M., Gillespie, S.M.,

Nelson, D.L., McConnochie, K.M. and Dozier, A.,

2013. A qualitative evaluation of a telemedicine

enhanced emergency care program for older adults.

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 61(4),

pp.571-576.

Shiue, I. and Sand, M., 2016. Quality of life in caregivers

with and without chronic disease: Welsh Health

Survey, 2013. Journal of Public Health, 39(1), pp.34-

44.

Siang, T. (2019). What is Design Thinking? [online] The

Interaction Design Foundation. Available at:

https://www.interactiondesign.org/literature/topics/des

ign-thinking [Accessed 1 Oct. 2019].

Koyanagi, A., DeVylder, J.E., Stubbs, B., Carvalho, A.F.,

Veronese, N., Haro, J.M. and Santini, Z.I., 2018.

Depression, sleep problems, and perceived stress

among informal caregivers in 58 low-, middle, and

high-income countries: a cross-sectional analysis of

community-based surveys. Journal of psychiatric

research, 96, pp.115-123.

Washington, K.T., Parker Oliver, D., Smith, J.B., McCrae,

C.S., Balchandani, S.M. and Demiris, G., 2018. Sleep

problems, anxiety, and global self-rated health among

hospice family caregivers. American Journal of

Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 35(2), pp.244-249.

Wells, J. and White, M. (2014) ‘The impact of the economic

crisis and austerity on the nursing and midwifery

professions in the Republic of Ireland – “boom”, “bust”

and retrenchment’. doi: 10.1177/1744987114557107.

HEALTHINF 2020 - 13th International Conference on Health Informatics

336