Continuity Editing in Documentary Film

Sandi Prasetyaningsih

1

and Gretchen Coombs

2

1

Multimedia and Networking Engineering, Politeknik Negeri Batam, Batam, Indonesia

2

Enabling Capability Platforms RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia

Keywords: Documentary, Editing, Continuity.

Abstract: This study focuses on continuity in documentary film editing. As a part of film’s pipeline production, editing

takes an important role in terms of delivering the story, especially for documentary which comprises many

unpredictable events during the production. This study uses one of the qualitative research methodologies

namely practice- based research. That methodology will be followed by case study method in order to provide

actual case study from the industry. Moreover, Whiteley and Gurrumul that won the best editing in 2017 and

2018 are used as case study in this research. Insight and techniques that are implemented in those films are

taken and then it is applied to the project. Three continuity techniques; 180º, over the shoulder, and action

match are implemented in the film editing, and it comes up with a reflective process in order to know what

type of continuity that can run well and what is not. As the result, the documentary film runs into two minutes

long while it is not as original plan since the project has not adequate material to implement the

aforementioned continuity techniques.

1

INTRODUCTION

For the creative project, “Indri” is edited in two min-

utes. It is a short biographical documentary about Siti

Nurlaila Indiriani, who is a master’s student of

Sustainable Energy Engineering at RMIT University.

According to the experience, working in documentary

film is a big challenge. The filmmaker confronted a

real situation where they did not have adequate mate-

rial, such as extra footage, as a supporting element to

enable them to deliver the story clearly to the viewer.

When they struggled to establish the story’s flow,

they ruined the continuity aspect of the edit. In

particular, several parts of the story ran too fast or

they could notice that the transition between shots

was too apparent.

The main objective of continuity in editing is to

preserve the audience’s attention and avoid audience

from being confused in the middle of the story. The

continuity itself should be applied smoothly in order

to prevent the viewer from feeling distracted by

transition between shots and to give time to the

viewer to catch the story flow moment by moment.

Consequently, in the

production process, the

filmmaker usually took a number of camera

placements in order to support them in creating

continuity during the editing process, such as 180º

rule, over the shoulder, and action match. These

existing shots will be used to explore continuity

editing techniques. Testing will be conducted on the

editing process to learn whether those camera

placements work to keep continuity or not.

According to Bricca (2017), there are no fixed

rules about editing documentaries. Moreover, the

research will focus on continuity techniques in

documentary editing. The editing in documentaries

has shown how challenging it is for the editor when

they have a large amount of material and are required

to choose the right shots to be used. The shots then

have to make it into an interactive visual while

maintaining both visual and narrative continuity.

To support this research, the practice-based re-

search is implemented as the methodology. Those

methodology is chosen since it is suitable for the

creative production. Batty and Kerrigan (2018) state

that screen production associated with creative

practice research enquiries can be represented in

several ways; practice-led-research, practice-as-

research, practice-based-re- search, and research-led

practice. Furthermore, there is case study method that

works in line with the practice-based research. The

case study method will generate the reflection in the

of the result in order to measure which part of

Prasetyaningsih, S. and Coombs, G.

Continuity Editing in Documentary Film.

DOI: 10.5220/0010351200270033

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Applied Engineering (ICAE 2020), pages 27-33

ISBN: 978-989-758-520-3

Copyright

c

2021 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

27

continuity methods that will work well and what is

not.

2

CONTINUITY EDITING

Continuity editing explores editing methods which

connects to a narrative system and enables the story

to be illustrated with less disruption and

disorientation to the audience (Orpen, 2003).

Furthermore, a study conducted by Kydd (2011) tells

that continuity editing develops a specific cinematic

space in which the spectator is bound into a certain

focus that connects with the action of the scene. The

main aim of continuity style is to transmit narrative

information smoothly and clearly over a series of

shots (Bordwell, Thompson, & Smith, 2013). In

addition, based on argument from Schaefer (1997),

‘when continuity techniques are done well, the

scene’s edit appears to be nearly invisible’.

Continuity in editing can be employed across

numerous elements in a film, such as story flow,

camera placement or angle, and cutting. Phillips

(2009) gives an illustration of camera angle eye line

matches from the scene of Life is Beautiful (1998)

when the man on his bi- cycle looks off-screen to the

left; the next shot shows what he is looking at. Over

the shoulder shots are usually employed for

conversation or dialogue scenes to display the

reaction and emotion of each actor. Furthermore,

continuity editing can also be reached by cutting the

action. For instance, a shot shows the end of the

subject’s movement and the next shot starts with a

different angle or distance.

2.1

180º Rule

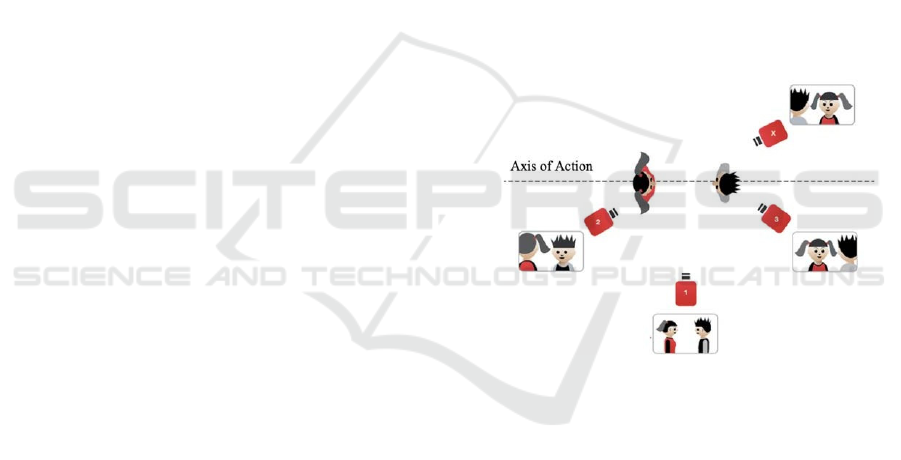

When working with 180º rule, continuity editing is

required to deal with the perception of spatial and

temporal (Magliano & Zacks, 2011). According to

Bordwell et al. (2013), to produce continuity style for

the scene’s space, the filmmaker can use the axis of

action, the center line or 180º rule.

It is essential to keep in mind during the

production that all shots must be taken from the same

side of “axis of action” or the imaginary line created

by the camera persons in their mind. If the camera

crosses the axis of action, it establishes the space

context and will create confusion for the viewer’s

understanding of the film’s visual. Firstly, the

background will change, which may confuse

audiences, and after seeing the right side of the

characters, the audience is exhibited the left side

which is another space that shifts the context of axis

of action. Secondly, the cutting between two shots

that go across the axis of action will create the

appearance of characters speaking with themselves,

as they replace each other’s spaces rather than each

other (Kydd, 2011). As an illustration, the first shot is

camera 3, then the camera position goes to X position;

when it turns into editing, the continuity of 180º rule

will not work, and it appears that the characters are

talking to themselves.

In terms of creating varieties of aesthetic framing,

the editor can employ one of the applicable angles of

shot from 180º system, such as over the shoulder

(OTS). This is usually used to reveal the conversation

between two persons and positioned either in place of

the listening character or just behind their shoulder

(camera 2 and 3 – see Figure 1). As stated by Smith

(2006), over the shoulder displays both characters on

screen at the same time; the shoulder and back of the

listener’s head is shown on one side of the screen

while the speaker’s face can be seen on the other side

of the screen.

Figure 1: 180º rule of camera spot, all shots must be taken

from camera 1, 2,3. A cut cross from camera X will create

a “discontinuity”.

2.2

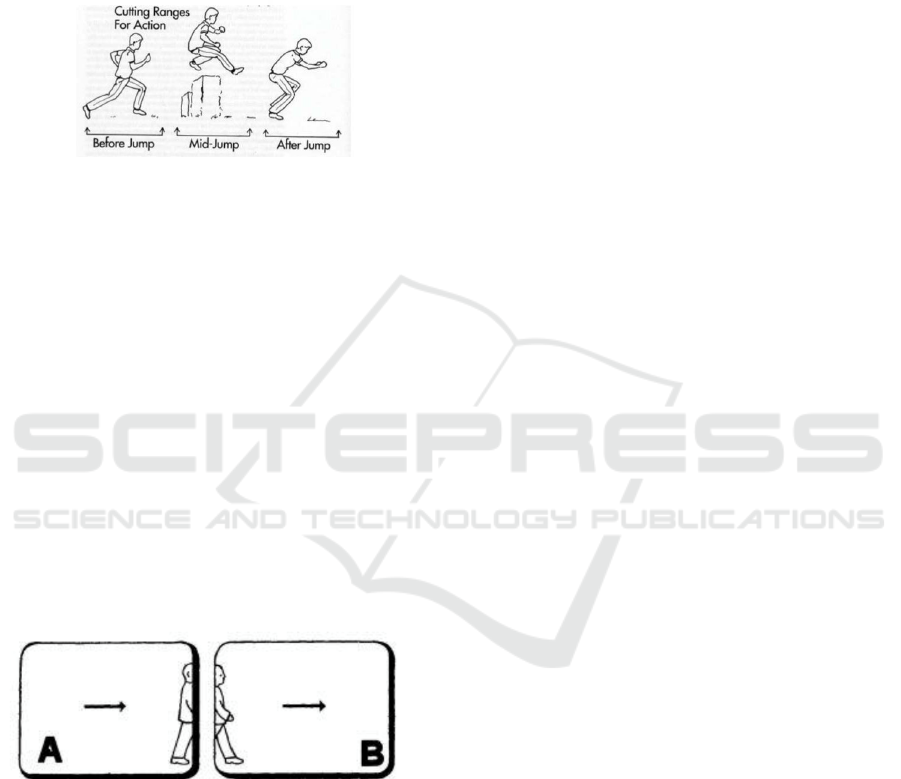

Match Action

One of the important components in generating

smooth continuity is to match action between two

construction shots. Nevertheless, the noticeable

problem to matching action is ‘to keep the action and

movement shown in consecutive shots accurately

continuous’ (Reisz & Millar, 1997). According to

(Kydd, 2011), match action is ‘part of the continuity

system that provides links between the shots, using

movements that are the same from one position to

another’. In addition, match cut is based on ‘visual

continuity, significance as well as similarity in angle

or direction’ (Dancyger, 2018).

As an example, when filming an actor, the camera

person can take several shots of the actor from many

ICAE 2020 - The International Conference on Applied Engineering

28

positions; it usually has several takes in the same shot

and scene, but it is important to note that the actor’s

movements must be made within the parameters of

the camera’s position. The editor then cuts the scene

by finding the point where the action between shots is

most closely matched. Nevertheless, the exact part to

cut is based on the editor’s sense of movement and

character (Katz, 1991).

Figure 2: Match action that could be cut between “before

jump” and “mid- jump”.

Match action is also related to maintaining the

screen direction in terms of having narrative

continuity. It is necessary to maintain the screen

direction to avoid audience confusion and to make the

characters distinct. The pattern of right-left or left-

right is the most main concern for keeping screen

direction. Burch (1973) suggests that if someone or

something in the screen on the left side enters the new

frame, it must be showing the space that closes from

the right; if this condition is not accomplished, there

has been a modification in the direction of a moving

person or objects. This explanation is also meet the

implementation of match exit/entering cut. When

someone enters a room, the first shot will show the

character on the right side of screen; then for the next

shot when the character has already entered the room,

the shot will show the character on the left side of the

screen

Figure 3: Match action exit/entrance.

3

METHODOLOGY

Candy and Ernest (2018) argue that new media arts as

one of the creative artefacts highlighting the creative

process and the works that are made; practice and

research operate together to construct new knowledge

that can be distributed and analysed. Based on this

argument, the research will be practice- based. To

support the methodology, the reflection will be used

as the method to approach

the case study. According

to (Starman, 2013), case study becomes the first type

of research that is utilized in qualitative methodology.

In addition, the reflection method will become part of

the learning process after analysing the case study,

implementing this into the creative practice, and

finally reflecting upon the creative practice. As such

as, the reflective practice is ‘intentional consideration

of an experience in light of particular learning

objectives’ (Hatcher & Bringle, 1997).

First and foremost, to have adequate material for

research, the study will be working on analysing two

documentary case studies from the Australian Award

of Cinema and Television Arts Awards (AACTA).

Whiteley won Best Editing in a Documentary in 2017

and Gurrumul was nominee for Best Editing in a

Documentary in 2018. We will look at the first three

minutes of each documentary film and take note of

how they approach the editing in general, as well as

focus on how they maintain the continuity throughout

the editing process. The case study analysis will

inform and improve the creative work. According to

Rowley (2002), case study is widely used since it

suggests various ways of gaining insight that might

not have been reached with other approaches; case

study is also applied for evolving more structured

tools that are important in surveys and experiments.

In the end, after exploration in continuity editing, the

research will reflect on which things work well and

which do not during the post- production process. The

reflection on the case study is part of the learning

process in the creative project. Ghauri (2004) says

that ‘a case study is both the process of learning about

the case and the product of our learning’.

4

CASE STUDY

The analysis will be concerned on the first three

minutes of Whiteley and Gurrumul. We picked up the

beginning because it usually determines the

audience’s interest to watch the whole film.

In addition, during the analysis process, the

reflection method will be used as an approach to the

learning process in which several points of analysis

will be implemented into the creative practice. The

reflection method is also used as a process of

problem-solving any issues that might occur in

executing the own creative work.

4.1

Whiteley

Whiteley is a documentary film about Australia’s

most iconic artist, Brett Whiteley, with duration of

Continuity Editing in Documentary Film

29

one hour and 35 minutes. This documentary uses a

notion of ‘in his own words’ and visualises

Whiteley’s story by using his notebooks, personal

letters, photographs, and other materials that support

his concept (IMDb, 2019).

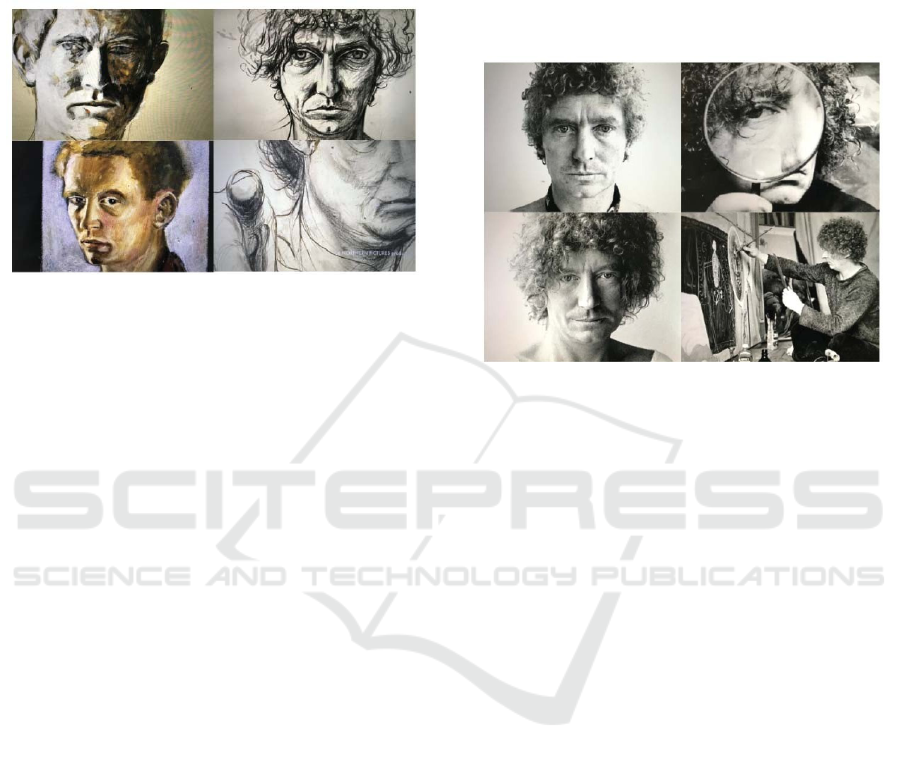

Figure 4: The opening visual of Whiteley documentary

film.

In the first scene, the documentary shows montage

sequences of black and white, and colourful images

to introduce Whiteley, explaining when and where he

was born. As mentioned by Frierson (2018),

‘montage in the broad sense describes a series of short

shots that compress time, space, or narrative

information, but it actually has several diverse

meanings. Montage sequences can be used as one of

the supplementary elements to support the visual

aesthetic. Leibowich (2007) supports the concept that

montage can be used as a device for establishing

spatial and temporal relationships within a movie.

As the montage sequence commences, there are a

small number of quick cuts, swift moves between

medium shots and close-up shots, and shifts in screen

direction. However, as the sequences begin, there is

no action shown of the character. It is a beautiful

opening of this documentary film, but as there is a

rapid shift from one shot to others, the cutting across

the screen with various directions does not allow for

the viewer to enjoy the visual moment of every

painting. In the classical Hollywood style, montage

describes a series of shots in which these shots do not

maintain the continuity concept, spatial and temporal

continuity, but the shots link together on every image

over time or across space (Orpen, 2003). This also

occurs in this documentary film; the montage

sequences refer to the creation of meaning within the

film and are used as a tool for introducing the

character by providing a series of beautifully crafted

pieces by Whiteley.

Moreover, the process by which the editor picked

the beautiful series of shots can be appreciated since

this component is really attractive for the audience.

With the combination of Whiteley’s self-portrait and

his amazing art pieces, this brings the audience to feel

more engaged in understanding his life story. The

black and white concept showing his portrait

distinguishes the expressions and activities of

Whiteley with his creative work.

Figure 5: Black and white self-potrait of Whiteley.

The voiceover in this scene is a narration from an

actor that provides an intimate effect that brings the

audience closer to knowing more about the existence

of Whiteley. Referring to Dancyger (2018), the

narration can aid the visual or directly give

understanding into the meaning; narration also can be

an important audio element in the documentary.

Narration assists in producing clear communication

to the viewer. Furthermore, the montage concept of

this documentary used in the beginning leaves no

space to visually show the dialogue part. As stated by

Bordwell, et al. (2013), montage sequences usually

lack dialogue, and the sequences usually come with

music as the back sound.

4.2

Gurrumul

This is a documentary film of one hour and 36

minutes telling the story of Indigenous artist,

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu. Born blind, his

community inspired him to write songs. ‘Gurrumul is

a portrait of an artist on the brink of global reverence,

and the struggles he and those closest to him faced in

balancing that which mattered most to him and

keeping the show on the road’ (IMDb, 2019). This

documentary film won two awards and was

nominated in five categories, including Best Editing

in a Documentary.

The opening of this film is beautiful; it reflects the

lived experience of Gurrumul, showing a black screen

with the voiceover of an ABC reporter interviewing

ICAE 2020 - The International Conference on Applied Engineering

30

Gurrumul. It represents what Gurrumul’s world is

like. The only thing he sees is dark and black; he can

hear anything, but he does not know how his

surroundings look. It is an amazing way to introduce

the character’s condition and his shy personality. The

next scene comes up with a medium shot portrait of

Gurrumul (see Figure 6), demonstrating the physical

appearance of his character.

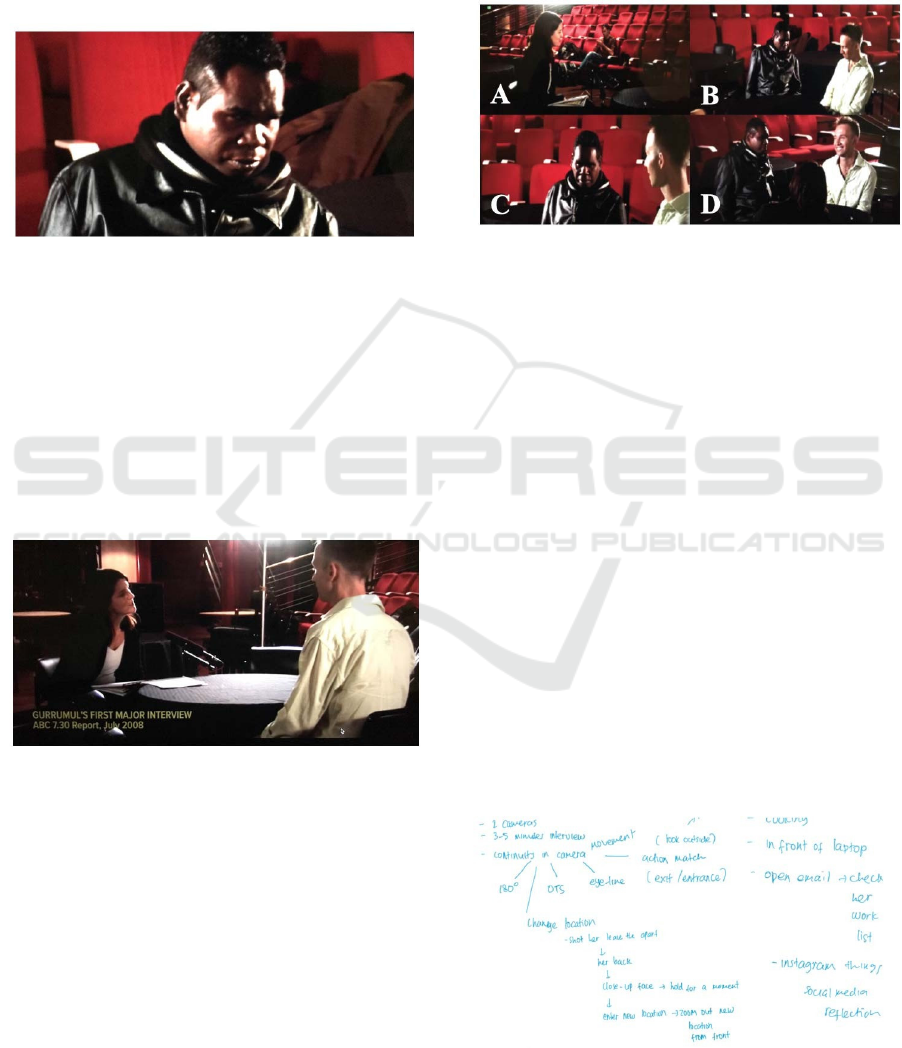

Figure 6: Medium close-up of character potrait.

Figure 7 shows the camera position within a 180º,

arch in which this 30º position rule means the camera

has to move at least 30º between two shots.

Nonetheless, it is essential to note that there cannot be

two shots that are too close to each other. If this

happens, it will confuse the viewer and reveal an

awareness of the cutting. When the camera does not

have adequate space between shots, a jump cut will

exist, and it is considered to break the rules of

continuity editing (Kydd, 2011).

Figure 7: 30º rule.

Figure 8 shows one of the scenes in Gurrumul that

implements the 180º rule camera placement system.

It is evident that the camera position is still in the axis

of action area that defines the spatial correlation

between three characters. The camera position moves

on one side of the line and moves to a different

position, but still does not cross the imaginary line.

Shot D in Figure 8 uses the over the shoulder shot,

which is usually used to show the dialogue action.

The camera is positioned on the back and shoulder of

the reporter while the other character’s B face can be

clearly seen on the other side of the screen. Although

there is an excess of head space in that shot, it creates

a space for the shoulder, but according to Magliano

and Zacks (2011), as long as the chosen shoulder area

is still within a 180º arc, the character will remain on

the correct side of the screen. The correct side of the

screen also preserves the direction of the shots, so the

audience will not be interrupted by any confusion

during their viewing of the film.

Figure 8: 180º rule

5

CREATIVE PRACTICE

IMPLEMENTATION

Having the freedom to play with the creative skills

during editing of the documentary, we wanted to

experiment with establishing the story flow, but it was

also important to us to consider the narrative

continuity.

Figure 9 shows the notes that we have written

during brainstorming; we picked up three main points

to be executed for the filming, such as 180º, over the

shoulder, and action match. Eye line match and

change location are additional points that are used for

shot and location continuity.

In addition, in the pre-production process, it is

important to have the list of questions ready that will

be asked to the subject. However, it is better to give

the questions to the subject prior to starting the

filming, so if there are any questions that make the

subject uncomfortable, these can be discussed

beforehand.

Figure 9: Note for the preproduction stage.

Continuity Editing in Documentary Film

31

Figure 10: List of questions.

Figure 11: Opening part of “Indri” documentary film.

The documentary starts by showing the shots

where Indri mentions some sentences that describe

Indri’s feeling about her contributions to any

organisation activities. This type of opening can make

the audience curious about what the story is about.

The next scene reveals the character walking from

one place to another, also known as change in

location. According to Dancyger (2018), ‘rather than

show the character [moving] from point A to point B,

the editor often shows her departing’ (2018, p. 305).

Hence, we decided to show the shot from over the

shoulder, shot from her back, and continued her

departing in the next shot to demonstrate that she

moves from one location to another location.

We use the montage sequence that we adapted

from the Whiteley documentary film (see Figure 4).

Even though this technique of editing does not offer

more in terms of effect in continuity, the montage

sequence can be helpful to construct and support the

story flow.

Figure 12 is the one scene that we use the 180º

camera placement rule in which that position is

commonly used to show two people interacting. Over

the shoulder is employed as 180º rule that shows two

characters in the same frame. Shot A and B in Figure

12 shows one side of the screen of the head and back

of the speaker’s; it gives the space to show another

character in another side of the screen. This is one

example of implementation of continuity, not only for

preserving the match action, but also for screen

direction continuity.

Figure 12: Change in location.

Figure 13: Montage sequence.

Figure 14: 180º rule.

6 CONCLUSIONS

It is important to pay more attention to continuity

during the editing process. However, during the

research and the creative practice, we realise that

continuity is not entirely about how we create the

continuity in visual, but we also need to consider

other components that will contribute to an interesting

film. For example, first, it is essential to have a

smooth flow of the story in addition to the inclusion

of continuity shots. During the production stage, we

recorded all the questions in order, but in the editing

ICAE 2020 - The International Conference on Applied Engineering

32

process, we needed to choose the relevant part of the

interview in terms of providing the particular

information to the audience and arrange the parts to

establish clear story flow. The flow of the story

emerges from the continuity which is achieved

through selection of the right shots to support the

content. At this stage, we know that having a lot of

extra footage can be beneficial for creative work.

Unfortunately, we did not allocate more time to shoot

more footage during the production, so we do not

have many options of shots to choose from to support

the visual aesthetic. Hence, we decided to cut down

the duration from the initial plan of three minutes as

the plan to two minutes with the consideration of

having clear story flow content and support from

available extra footage. It is because we do not want

to enforce to have three-minute documentary, but the

story and visual are not credible.

The main concern of the research relates to the

application of several camera angle techniques and

correct placement; for the two-minute length of the

project, the big challenge for us has been that we

cannot use the selected techniques throughout the

entire film. Hence, we need to combine and play with

the shots of the interview section, apply the camera

techniques, and put the extra footage in to help us give

visual variation to attract the audience’s attention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The first author would like thank to RMIT University

for giving a lot of experience during the study time;

especially to Gretchen as supervisor who is patiently

give precious feedback during finishing this research.

In addition, another thanks to Batam State

Polytechnic for funding support in publishing this

paper.

REFERENCES

Batty, C, Kerrigan, S., 2018. Screen production research:

creative practice as a mode of enquiry, Cham: Springer

International Publishing, Cham.

Bordwell, D, Thompson, K, Smith, J., 2013. Film art: an

introduction, McGraw-Hill New York.

Bricca, J., 2017. Documentary editing: principles and

practice, Taylor & Francis Group.

Burch, N., 1973. Theory of film practice (cinema two),

London: Secker and Warburg.

Candy, LE, Ernest, 2018, 'Practice-based research in the

creative arts: foundations and futures from the front

line', Leonardo, vol. 51, no. 1, pp. 63-69.

Dancyger, K., 2018. The technique of film and video

editing: history, theory, and practice, Focal Press.

Frierson, M., 2018. Film and video editing theory: how

editing creates meaning, Taylor & Francis.

Ghauri, P., 2004. Designing and conducting case studies in

international business research.

Hatcher, J.A., Bringle, R. G., 1997. Reflection: bridging the

gap between service and learning. College Teaching,

vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 153-158.

IMDb, n.d. Gurrumul, Retrieved May 4

th

, 2019, from

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7737502/?ref_=nv_sr_1?

ref_=nv_sr_>.

IMDb, n.d. Whiteley, Retrieved May 4

th

, 2019, from

<https://www.imdb.com/title/tt6021894/?ref_=fn_al_tt

_1>.

Katz, S.D., 1991. Film directing shot by shot: visualizing

from concept to screen, Gulf Professional Publishing.

Kydd, E., 2011. The critical practice of film: an

introduction, Macmillan International Higher

Education.

Leibowich, J., 2007. Montage, The Chicago School of

Media Theory, Retrieved May 3th, 2019, from

<https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywo

rds/montage/>.

Magliano, J.P., Zacks, J.M., 2011. The impact of continuity

editing in narrative film on event segmentation.

Cognitive Science, vol. 35, no. 8, pp. 1489-1517.

Orpen, V., 2003. Film editing: the art of the expressive,

Wallflower, London.

Phillips, W., 2009. Film an introduction, Bedford/St.

Martin’s, Boston.

Reisz, K., Millar, G., 1977. The technique of film editing,

Focal Press, Burlington.

Rowley, J., 2002. Using case studies in research.

Management Research News, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 16-27.

Schaefer, RJ 1997, 'Editing strategies in television news

documentaries', Journal of Communication, vol. 47, no.

4, pp. 69-88.

Starman, A.B., 2013. The case study as a type of qualitative

research. Journal of Contemporary Educational

Studies/Sodobna Pedagogika, vol. 64, no. 1.

Continuity Editing in Documentary Film

33