The Impact of Regular Outdoor Cycling and Gender on Technology

Trust and Distrust in Cars, and on Anxiety

Klemens Weigl

1,2 a

1

Human-Computer Interaction Group, Technische Hochschule Ingolstadt (THI), Esplanade 10, Ingolstadt, Germany

2

Department of Psychology, Catholic University Eichst

¨

att-Ingolstadt, Germany

Keywords:

Outdoor Cycling, Technology Trust, Cars, Anxiety, Age, Gender.

Abstract:

Regular cycling is well-known for its numerous benefits on physiological and mental health. However, cyclists

are confronted with numerous other road users with different modes of transport which are more harmful to

nature and may be even more dangerous. As yet, there has been no study which focuses jointly on the potential

influence of trust and distrust in cars, anxiety, age, and gender in the context of regular outdoor cycling.

Consequently, we carried out a questionnaire study and queried 114 participants (60 female (34 cyclists); 54

male (32 cyclists)). We assessed trust and distrust in cars, trait anxiety in a non-clinical context, age, and

gender. Our results reveal that cyclists rate distrust in cars with significantly greater values when compared to

non-cyclists. Moreover, we found that women assign substantially lower ratings to trust and higher ratings to

distrust in cars than men, regardless whether they are cyclists or not. Additionally, women report significantly

higher values on anxiety in a non-clinical context. Finally, our results indicate that older people are less likely

to engage with regular outdoor cycling. We conclude that female and male cyclists are more critical on distrust

in cars than non-cyclists, though they are not more anxious.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, regular outdoor cycling gained pop-

ularity for several reasons. First, cycling is associ-

ated with positive effects on physiological and mental

health and wellbeing (Christmas et al., 2010; Wan-

ner et al., 2012; Laverty et al., 2013; De Hartog

et al., 2010). Second, cycling attracted new atten-

tion, because climate change became one of the ma-

jor challenges of the 21st century. Melting ice masses

and glaciers, rising sea levels, acidifying oceans,

climate fluctuations, and increasing carbon dioxide

(CO2) levels in the atmosphere negatively affect peo-

ple, animals, and nature (Haines et al., 2006; G20,

2017; McMichael et al., 2006). Climatological re-

search identified links between the anthropogenic in-

fluence and the unusually rapid rise in temperature

which is due to the accumulation of greenhouse gases

in the earth’s atmosphere (McMichael et al., 2006;

Chapman, 2007; Karl and Trenberth, 2003). Thereby,

about 30 percent of all CO

2

emissions are attributed to

the transport sector. Therefore, an increasing number

of people ride a bicycle for environmental reasons.

a

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2674-1061

1.1 Modal Shift to Cycling

Although the awareness of environmental problems

and the positive effects of cycling is slowly increas-

ing, the majority of all people around the globe, does

not cycle regularly, if at all. Long-term cycling ini-

tiatives in cities which focus only on cycling infras-

tructure and on sports scientific support clearly indi-

cated that they may have no influence on the adop-

tion of bike riding compared to cities with no ini-

tiatives (Goodman et al., 2013a; Goodman et al.,

2013b). However, other empirical studies on cycling

safety (e.g., bike routes on less frequented roads or

separating cyclists from traffic through infrastructure,

etc.) also showed, that they may have a positive im-

pact on attracting more people to cycling (Dozza and

Werneke, 2014; Pucher and Dijkstra, 2000; Pucher

and Buehler, 2008; G

¨

otschi et al., 2016). In gen-

eral, cycling is highly interrelated with the interaction

with other road users with different modes of trans-

port. Thereby, trust in other vehicles, especially in

cars, plays a crucial role. Trust in technology and

user acceptance have attracted interest especially in

the field of the mobility of the future such as auto-

mated driving (K

¨

orber et al., 2018; Payre et al., 2016),

Weigl, K.

The Impact of Regular Outdoor Cycling and Gender on Technology Trust and Distrust in Cars, and on Anxiety.

DOI: 10.5220/0010135600830089

In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support (icSPORTS 2020), pages 83-89

ISBN: 978-989-758-481-7

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

83

(Wintersberger et al., 2016; Wintersberger and

Riener, 2016). However, even automated vehicles

(AVs) are not capable of reducing the amount of CO2

emissions to the same extend as bicycle or e-bikes.

Despite the realistic scenario that AVs, public trans-

port, e-scooters, and

(e-)bicycles may constitute future road traffic, there

are numerous people who are sceptical about technol-

ogy and cars. Hence, it is necessary to study tech-

nology trust in relation with different means of trans-

port. Additionally, it was found that cycling reduced

the Hoffmann reflex which is deemed a neuromuscu-

lar substrate of anxiety (Bulbulian and Darabos, 1986;

deVries et al., 1981; Petruzzello et al., 1991) as well

as state and trait anxiety (Motl et al., 2004).

However, there exists no study which explores the

relationship between regular outdoor cycling, tech-

nology trust and distrust in cars, trait anxiety in a non-

clinical context, duration of the daily commute per car

and by public transport, age, and gender.

1.2 The Present Study

Consequently, we carried out a questionnaire study

and investigated the following research questions

(RQs) and hypotheses (Hs).

RQ1 (Trust and Distrust in Cars): How is the im-

pact of female and male cyclists versus non-cyclists

on trust in cars and distrust in cars?

• H

1.1

: We hypothesize that female and male cy-

clists assign significantly lower ratings to trust in

cars and sufficiently higher ratings to distrust in

cars than non-cyclists, respectively.

• H

1.2

: Across cyclists and non-cyclists, we expect

women to report substantially smaller preferences

on trust in cars and greater values on distrust in

cars than men, respectively.

RQ2 (Anxiety): How is the influence of anxiety on

female and male cyclists and non-cyclists?

• H

2

: We assume that women assign noticeably

greater ratings to trait anxiety in a non-clinical

context than men, regardless if they are cyclists

or not.

RQ3 (Age and Duration of Daily Commute): How

is regular outdoor cycling associated with age, dura-

tion of the daily commute by car, and duration of the

daily commute by public transport?

• H

3.1

: We suppose that regular outdoor cycling is

negatively correlated with age (i.e., younger peo-

ple cycle more than older people).

• H

3.2

: Moreover, we hypothesize no substantial

association between regular outdoor cycling and

the duration of the daily commute by car or by

public transport, respectively.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

We queried 114 participants of which 60 were female

(34 cyclists) and 54 male (32 cyclists; cf. Table 1).

The age of all participants varied between 21 to 85

years (M = 53.4; SD = 18.6). The mean age of women

was 51.4 years (SD = 18.8) and of men 55.6 years (SD

= 18.3). All participants were fluent in German the

language in which the questionnaires were provided,

consumed no alcohol or drugs, and reported no diag-

nosis of a psychiatric or neurological disorder. The

duration of the daily commute by car was on average

28 minutes (SD = 24; n = 60), by public transport 33

minutes (SD = 32; n = 19), and by bicycle 13 min-

utes (SD = 15; n = 42). In total 51 participants pos-

sessed a general qualification for university entrance,

17 a university of applied sciences entrance qualifica-

tion, 25 a high-school diploma, 19 a secondary mod-

ern school qualification, one person graduated from

a polytechnic school, and one from a professional

academy. Thirty-two participants reported that they

never experienced a traffic accident. However, 56 re-

ported that they experienced a non-severe, and 26 a

severe traffic accident.

Table 1: Sample Sizes of Female and Male Cyclists and

Non-Cyclists (N = 114).

Cyclists Non-Cyclists Sum

Female 34 26 60

Male 32 22 54

Sum 66 48 114

2.2 Design and Materials

We conducted a cross-sectional questionnaire study

and adopted a two factorial (2 x 2) between-subjects

design with gender and cycling (i.e., cyclists vs. non-

cyclists) as between-subjects factors (cf. Table 1).

Our dependent variables were trust in cars, distrust in

cars, and anxiety in a non-clinical context. We mea-

sured technology trust by the trust scale (Jian et al.,

2000) with the two dimensions of trust (7 items; Cron-

bach’s α = .87) and distrust in technology (5 items;

Cronbach’s α = .88) on a 7-point Likert scale an-

chored at 1 (not at all) and 7 (extremely). Typical

items are ”The system of car and driver offers safety.”

or ”I am suspicious of the intentions, actions, and out-

icSPORTS 2020 - 8th International Conference on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support

84

put of the system of car and driver.” (Note: Due to

technical problems, the data of one questionnaire item

of the trust dimension were not transferred via the on-

line system. Hence, we collected data from 6 instead

of 7 items. However, the data of all other dimensions,

scales, and demographic variables were complete.).

Additionally, we assessed anxiety in a non-clinical

context (7 items; Cronbach’s α = .65) on a 7-level

Likert scale ranging from 1 (applies not at all) to 7

(applies fully). Example items are ”It is difficult for

me to talk with strangers.” or ”I try to avoid difficult

things.” (Mohr and M

¨

uller, 2004).

2.3 Procedure

Before the beginning of the study, each participant re-

ceived an introduction to the background of the study

and was invited to ask questions throughout the en-

tire study. Then everyone provided written informed

consent. After this introductory part, all participants

filled the questionnaire items of the trust scale, the

questions of anxiety in a non-clinical context, and ad-

ditional demographic variables such as age, gender,

regular outdoor cycling (yes or no), duration of the

daily commute by car, public transport, and bicycle.

Upon completion of the questionnaire part, everyone

received the contact details of the examiner, in case of

any questions. All data for this study were collected

anonymously and online via LimeSurvey (Version

3.12.1 + 180616). The examiner was either present

(especially for older people) or could be reached by

phone, email, or video-call during the entire study

duration which ranged from 20 to 30 minutes. The

participants did not receive financial compensation.

However, all of them were invited to provide their

email addresses if they were interested in the results

of the study.

2.4 Supplementary Materials

We support the open science movement and supply

the data set on OSF: https://osf.io/q76dj/ .

2.5 Statistical Analyses

We set the significance level to α = .05, if not stated

otherwise (e.g., in case of Bonferroni correction).

Therefore, all results with p < α are reported as sta-

tistically significant. The items of all questionnaires

were positively coded. Hence, the sum scores were di-

rectly computed for the trust and distrust dimensions

of the trust scale, and the anxiety dimension of the

questionnaire on anxiety in a non-clincial context. For

all data analyses we applied IBM

R

SPSS

R

Statis-

tics, Version 25 (IBM Corp., 2017).

In the beginning of the statistical analyses, we

checked the statistical prerequisites and tested all data

for normality and variance homogeneity. Concerning

RQ1 and RQ2, normality was met for 9 out of 12

conditions (2 (gender) x 2 (cycling) x 3 (trust, dis-

trust, anxiety) = 12). We conducted parametric statis-

tical analyses, because the cell sample sizes were all

fairly equally balanced (cf. Table 1), and skewness

and kurtosis as well as the QQ-plots revealed a good

distributional behavior of the data. Additionally, we

investigated RQ3 and computed point-biseral corre-

lations because of the dichotomous variable cycling

(i.e., cyclists vs. non-cyclists).

3 RESULTS

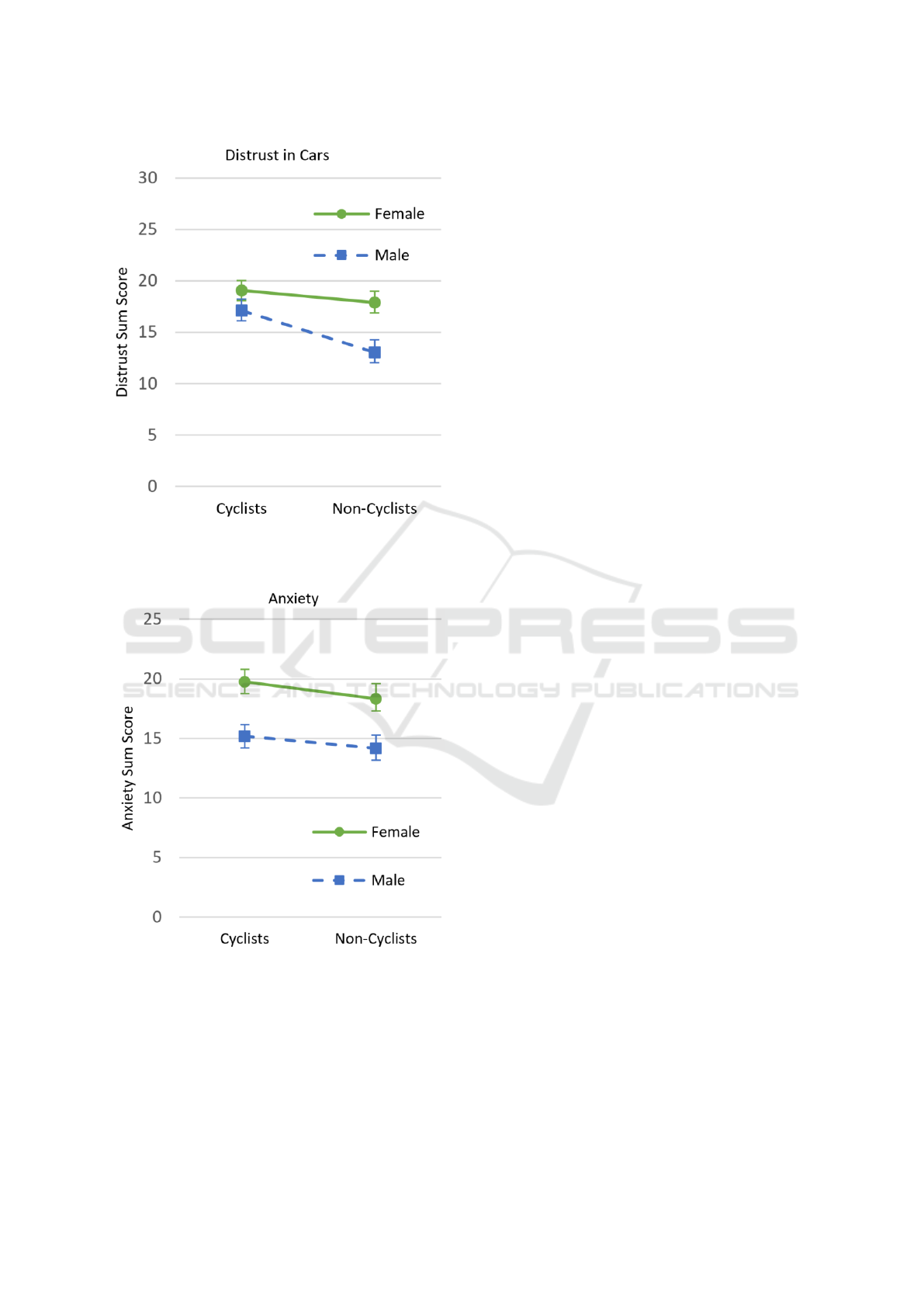

RQ1 (Trust and Distrust in Cars): We applied

a two-factorial multivariate analyses of variances

(MANOVA) with gender and cycling as grouping

variables and tested the two dependent variables trust

(H

1.1

) and distrust in cars (H

1.2

). Thereby, we found

that female and male cyclists assign roughly the same

ratings to trust in cars as non-cyclists (cf. Table 2 and

3, and Figure 1). However, our results revealed suf-

ficiently higher ratings to distrust in cars than non-

cyclists, respectively (cf. Table 2 and 3, and Figure

2). Hence, we could only party accept H

1.1

. Across

cyclists and non-cyclists, we found that women report

substantially smaller preferences on trust in cars and

greater values on distrust in cars than men, respec-

tively. Therefore, we could accept H

1.2.

.

RQ2 (Anxiety): Then, we applied an univariate

analysis of variances (ANOVA) and tested whether

trait anxiety in a non-clinical context differs between

female and male cyclists and non-cyclists, respec-

tively. Our results revealed that women assign signif-

icantly greater ratings to trait anxiety in a non-clinical

context than men, regardless if they are cyclists or not

(cf. Table 2 and 4, and Figure 3). Hence, we could

accept H

2

.

RQ3 (Age and Duration of Daily Commute):

Finally, we investigated if regular outdoor cycling is

associated with age, duration of the daily commute

by car, and duration of the daily commute by pub-

lic transport. We found that regular outdoor cycling

is negatively correlated with age (i.e., younger people

cycle more than older people) and could accept H

3.1

.

However, our data did not reveal a substantial associ-

ation neither between regular outdoor cycling and the

duration of the daily commute by car, nor by public

transport. Therefore, we could not confirm H

3.2

(cf.

Table 2 and 5).

The Impact of Regular Outdoor Cycling and Gender on Technology Trust and Distrust in Cars, and on Anxiety

85

Table 2: Mean Scores and Standard Deviation for Measures of Trust, Distrust, Anxiety, and Age as a Function of Gender and

Cyclists versus Non-Cyclists.

Trust Distrust Anxiety in a Non- Age in

in Cars in Cars Clinical Context Years

Group M SD M SD M SD M SD

Female

Cyclists 22.50 7.12 19.06 5.79 19.74 6.12 46.47 19.70

Non-Cyclists 23.04 5.48 17.88 5.74 18.31 6.46 57.77 15.72

Male

Cyclists 26.97 7.91 17.09 6.42 15.19 5.43 53.53 17.90

Non-Cyclists 27.59 6.40 13.05 5.75 14.18 5.18 58.59 18.77

Note. Trust, Distrust, and Anxiety ... sum scores of latent questionnaire dimensions.

Table 3: Two-way Multivariate and Univariate Analyses of Variances for the Measures of Trust and Distrust in Cars.

Univariate

Multivariate Trust in Cars Distrust in Cars

Source F

c

p η

2

F

d

p η

2

F

d

p η

2

Cycling (C)

a

3.28 .041 .06 .20 .659 .00 5.32 .023 .05

Gender (G)

b

6.59 .002 .11 11.86 .001 .10 9.02 .003 .08

C x G 1.19 .307 .02 .00 .975 .00 1.61 .21 .01

Note. Multivariate F ratios were generated from Pillai’s statistic. Trust and Distrust in Cars

... sum scores of latent questionnaire dimensions.

a

Cycling ... cyclists versus non-cyclists.

b

Gender ... women versus men.

c

Multivariate df = 2, 109.

d

Univariate df = 1, 110.

Text in bold highlights statistically significant findings.

Table 4: Two-way Univariate Analyses of Variances for the

Measure Anxiety in a Non-Clinical Context.

Anxiety

Source F(1, 110) p η

2

Cycling (C)

a

1.12 .276 .01

Gender (G)

b

15.22 .000 .12

C x G 0.04 .850 .00

Note. Anxiety ... sum score of the latent

questionnaire dimension.

a

Cycling ... cyclists versus non-cyclists.

b

Gender ... women versus men.

Table 5: Point-biseral Correlation Coefficients of Age, Du-

ration of the Daily Commute by Car, and Duration of the

Daily Commute by Public Transport with Cycling.

Cycling

a

Variable n r p

Age 114 -.22 .019

Commute by Car

b

60 -.09 .502

Commute by Public Transport

b

19 -.17 .482

a

Cycling ... cyclists (= 1) versus non-cyclists (= 0).

b

Duration measured in minutes.

Figure 1: Means and standard errors of the mean for trust in

cars as a function of gender and cyclists versus non-cyclists.

4 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this cycling study was to investigate

the influence of regular outdoor cycling and gender

icSPORTS 2020 - 8th International Conference on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support

86

Figure 2: Means and standard errors of the mean for dis-

trust in cars as a function of gender and cyclists versus non-

cyclists.

Figure 3: Means and standard errors of the mean for anxiety

in a non-clinical context as a function of gender and cyclists

versus non-cyclists.

on technology trust and distrust in cars, and on non-

clinical anxiety. Our findings highlight crucial interre-

lations of these important technology-related dimen-

sions and contribute to the new trend on cycling re-

search with the overarching goal to facilitate a modal

shift to cycling.

The first objective was to study the impact of fe-

male and male cyclists versus non-cyclists on trust in

cars and distrust in cars (RQ1). Our findings indicate

that female and male cyclists may have roughly the

same technology trust in cars as non-cyclists. How-

ever, cyclists seem to have a greater distrust in cars

than non-cyclists. Additionally, women tend to be

more critical than men because of their stated smaller

preferences on trust in cars and greater values on dis-

trust in cars, whether or not they are cyclists.

Our second objective was to investigate the influ-

ence of non-clinical anxiety on female and male cy-

clists and non-cyclists (RQ2). We found that women

seem to have greater trait anxiety in a non-clinical

context than men, regardless if they are cyclists or not.

These findings are in line with other previous studies

which, however, did not focus on cycling (Bahrami

and Yousefi, 2011; Hantsoo and Epperson, 2017;

Howell et al., 2001; Kendler et al., 1992; McLean and

Anderson, 2009; Pigott, 2003; Yonkers et al., 2003).

The third objective was to elaborate if regular out-

door cycling is associated with age, duration of the

daily commute by car, and duration of the daily com-

mute by public transport (RQ3). The results indicate

that younger people cycle more than older people.

Interestingly, we found no association between

regular outdoor cycling and the duration of the daily

commute by car or by public transport, respectively.

However, this finding is based on smaller sample sizes

than all other results mentioned before.

As yet, to the best of our knowledge, there exists

no cycling study which focuses jointly on technology

trust and distrust in cars, anxiety, age, and duration

of the daily commute. Hence, our results provide an

important link to begin to fill this research gab. Nev-

ertheless, in future studies, it will be necessary to ad-

dress these research questions again with greater sam-

ple sizes and in relation with other personality traits.

Thereby, it could be highly interesting to also focus

on the impact of environmental perception on the de-

cision whether or not someone regularly rides a bicy-

cle. Additionally, it should be also focused on policies

which positively promote active urban travel in rela-

tion with larger health and environmental benefits, in-

stead of focusing solely on lower-emission motor ve-

hicles (Woodcock et al., 2009).

5 CONCLUSION

In this study, we highlighted the impact of regular

outdoor cycling and gender on trust and distrust in

cars, and on anxiety to foster the understanding of cy-

The Impact of Regular Outdoor Cycling and Gender on Technology Trust and Distrust in Cars, and on Anxiety

87

clists and non-cyclists. In doing so, we contribute to

this newly emerging global debate of the necessity to

support cycling for modal shift to tremendously re-

duce the amount of CO2 emissions, if people regu-

larly choose the bicycle as means of transport (also in

combination with public transport) instead of the car.

On top of this, cycling is associated with numerous

health benefits for people. In the following, we sum

up the highlights of our study:

1. Cyclists and non-cyclists report roughly the same

ratings of technology trust in cars.

2. Cyclists report substantially greater values of

technology distrust in cars than non-cyclists.

3. Regardless if someone is a cyclist or not, women

assign smaller values to trust in cars, and greater

values to distrust in cars than men, respectively.

4. Although women assign significantly greater rat-

ings to trait anxiety in a non-clinical context than

men, it has no mediating positive or negative ef-

fect on cycling.

5. Regular outdoor cycling is negatively correlated

with age. Hence, older people should be moti-

vated and supported more than younger people by

local campaigns of policy makers and cycling ac-

tivists.

Mobility of the future will not only be constituted

with automated vehicles, but also to a large extent

with (electric) sensor bicycles which will be able to

communicate with all means of transport. Hence, fu-

ture studies will be unequivocally necessary to better

understand psychological and motivational aspects of

regular outdoor cycling.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am very grateful to Eva Quednau for collecting these

data.

REFERENCES

Bahrami, F. and Yousefi, N. (2011). Females are more anx-

ious than males: a metacognitive perspective. Ira-

nian journal of psychiatry and behavioral sciences,

5(2):83.

Bulbulian, R. and Darabos, B. L. (1986). Motor neuron

excitability: the hoffmann reflex following exercise of

low and high intensity. Medicine & Science in Sports

& Exercise.

Chapman, L. (2007). Transport and climate change: a re-

view. Journal of transport geography, 15(5):354–367.

Christmas, S., Helman, S., Buttress, S., Newman, C., and

Hutchins, R. (2010). Cycling, safety and sharing the

road: qualitative research with cyclists and other road

users. Road Safety Web Publication, 17.

De Hartog, J. J., Boogaard, H., Nijland, H., and Hoek,

G. (2010). Do the health benefits of cycling out-

weigh the risks? Environmental health perspectives,

118(8):1109–1116.

deVries, H. A., Wiswell, R. A., Bulbulian, R., and Moritani,

T. (1981). Tranquilizer effect of exercise: acute effects

of moderate aerobic exercise on spinal reflex activa-

tion level. American Journal of Physical Medicine &

Rehabilitation, 60(2):57–66.

Dozza, M. and Werneke, J. (2014). Introducing naturalistic

cycling data: What factors influence bicyclists’ safety

in the real world? Transportation research part F:

traffic psychology and behaviour, 24:83–91.

G20 (2017). Klimawandel — eine Faktenliste.

https://www.klimafakten.de/sites/default/files/

downloads/klimafakten2017g20.pdf.

Goodman, A., Panter, J., Sharp, S. J., and Ogilvie, D.

(2013a). Effectiveness and equity impacts of town-

wide cycling initiatives in england: a longitudinal,

controlled natural experimental study. Social science

& medicine, 97:228–237.

Goodman, A., Sahlqvist, S., Ogilvie, D., iConnect Con-

sortium, et al. (2013b). Who uses new walking and

cycling infrastructure and how? longitudinal results

from the uk iconnect study. Preventive medicine,

57(5):518–524.

G

¨

otschi, T., Garrard, J., and Giles-Corti, B. (2016). Cycling

as a part of daily life: a review of health perspectives.

Transport Reviews, 36(1):45–71.

Haines, A., Kovats, R. S., Campbell-Lendrum, D., and

Corval

´

an, C. (2006). Climate change and human

health: impacts, vulnerability and public health. Pub-

lic health, 120(7):585–596.

Hantsoo, L. and Epperson, C. N. (2017). Anxiety disorders

among women: a female lifespan approach. Focus,

15(2):162–172.

Howell, H. B., Brawman-Mintzer, O., Monnier, J., and

Yonkers, K. A. (2001). Generalized anxiety disor-

der in women. Psychiatric Clinics of North America,

24(1):165–178.

IBM Corp. (Released 2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Win-

dows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Jian, J.-Y., Bisantz, A. M., and Drury, C. G. (2000). Foun-

dations for an empirically determined scale of trust in

automated systems. International journal of cognitive

ergonomics, 4(1):53–71.

Karl, T. R. and Trenberth, K. E. (2003). Modern global

climate change. science, 302(5651):1719–1723.

Kendler, K. S., Neale, M. C., Kessler, R. C., Heath, A. C.,

and Eaves, L. J. (1992). Generalized anxiety disorder

in women: a population-based twin study. Archives of

General Psychiatry, 49(4):267–272.

K

¨

orber, M., Baseler, E., and Bengler, K. (2018). Introduc-

tion matters: Manipulating trust in automation and

reliance in automated driving. Applied ergonomics,

66:18–31.

icSPORTS 2020 - 8th International Conference on Sport Sciences Research and Technology Support

88

Laverty, A. A., Mindell, J. S., Webb, E. A., and Millett, C.

(2013). Active travel to work and cardiovascular risk

factors in the united kingdom. American journal of

preventive medicine, 45(3):282–288.

McLean, C. P. and Anderson, E. R. (2009). Brave men

and timid women? a review of the gender differ-

ences in fear and anxiety. Clinical psychology review,

29(6):496–505.

McMichael, A. J., Woodruff, R. E., and Hales, S. (2006).

Climate change and human health: present and future

risks. The Lancet, 367(9513):859–869.

Mohr, G. and M

¨

uller, A. (2004). Angst im nichtklinischen

kontext. Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher

Items und Skalen (ZIS).

Motl, R. W., O’connor, P. J., and Dishman, R. K. (2004).

Effects of cycling exercise on the soleus h-reflex and

state anxiety among men with low or high trait anxi-

ety. Psychophysiology, 41(1):96–105.

Payre, W., Cestac, J., and Delhomme, P. (2016). Fully auto-

mated driving: Impact of trust and practice on manual

control recovery. Human factors, 58(2):229–241.

Petruzzello, S. J., Landers, D. M., Hatfield, B. D., Kubitz,

K. A., and Salazar, W. (1991). A meta-analysis on the

anxiety-reducing effects of acute and chronic exercise.

Sports medicine, 11(3):143–182.

Pigott, T. A. (2003). Anxiety disorders in women. Psychi-

atric Clinics of North America.

Pucher, J. and Buehler, R. (2008). Cycling for everyone:

lessons from europe. Transportation research record,

2074(1):58–65.

Pucher, J. and Dijkstra, L. (2000). Making walking and

cycling safer: lessons from europe. Transportation

Quarterly, 54(3):25–50.

Wanner, M., G

¨

otschi, T., Martin-Diener, E., Kahlmeier, S.,

and Martin, B. W. (2012). Active transport, phys-

ical activity, and body weight in adults: a system-

atic review. American journal of preventive medicine,

42(5):493–502.

Wintersberger, P., Frison, A.-K., Riener, A., and Boyle,

L. N. (2016). Towards a personalized trust model

for highly automated driving. Mensch und Computer

2016–Workshopband.

Wintersberger, P. and Riener, A. (2016). Trust in technology

as a safety aspect in highly automated driving. i-com,

15(3):297–310.

Woodcock, J., Edwards, P., Tonne, C., Armstrong, B. G.,

Ashiru, O., Banister, D., Beevers, S., Chalabi, Z.,

Chowdhury, Z., Cohen, A., et al. (2009). Public

health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-

gas emissions: urban land transport. The Lancet,

374(9705):1930–1943.

Yonkers, K. A., Bruce, S. E., Dyck, I. R., and Keller, M. B.

(2003). Chronicity, relapse, and illness—course of

panic disorder, social phobia, and generalized anxiety

disorder: findings in men and women from 8 years of

follow-up. Depression and anxiety, 17(3):173–179.

The Impact of Regular Outdoor Cycling and Gender on Technology Trust and Distrust in Cars, and on Anxiety

89