An Overview of EFL Reading Comprehension

Kusumarasdyati

1

and Farah Ramadhani

2

1

Universitas Negeri Surabaya

2

Universitas Brawijaya

Keywords: Reading Comprehension, Reading Processes, EFL

Abstract: This paper provides a general overview of reading comprehension as a essential construct in language

learning. Reading comprehension is defined as the process of constructing meaning from the printed piece

of writing, involving cognitive and social factors. Reading processes are classified into three types: bottom-

up, top-down and interactive. In order to comprehend a text well, the proponents of the reading-universal

hypothesis believe that good ability in comprehending ideas in the first language (L1) is associated with

good comprehension in FL. On the contrary, those who support the short-circuit hypothesis argue that such

a transfer from L1 to FL occurs after the readers reach a certain threshold level of proficiency in FL. Some

implications are suggested for language teachers who teach reading comprehension.

1 INTRODUCTION

Good reading comprehension has been considered

indispensable in the academic setting as it is one of

the factors that determines successful learning. To

assist learners in becoming good readers, language

teachers need to understand the basic concepts of

reading comprehension. This paper reviews a

number of issues in reading comprehension. It

begins with the most fundamental question about

this construct: what is reading comprehension? The

definition is discussed first in order to clarify what

the term ‘reading comprehension’ means.

Next, this paper will examine the cognitive

processing that operates during reading, which may

be bottom-up, top-down or interactive in nature.

After the review of general concepts about reading,

the focus will be sharpened further into reading in

english as a foreign language (fl). Lastly, another

section will contrast reading in fl and reading in the

first language to make it clear that these two differ

for several reasons (

Alderson et all, 2000).

2 METHODOLOGY

2.1 Cognitive Processes in Reading

It is generally agreed that comprehension processes

may be approached cognitively in two ways, namely

bottom-up and top-down (Alderson, et all, 2000;

Nuttall, 1996

). Sometimes referred to as the data-

driven model, the bottom-up model views decoding

and linguistic comprehension as central processes in

reading (Gough, 1972; Hoover et all, 1990). Thus

the reader performs this process by decoding the

printed letters first, followed by such larger syntactic

chunks as words, phrases and sentences. When this

perception is completed, the reader can construct

meaning based on them. It operates serially in that

the direction goes strictly in such an order, from the

lowest level (letters) to the highest one (sentences),

and the higher level cannot possibly affect the

perception of the previous levels. While the bottom-

up model holds some truth, it seems an

oversimplification to claim that reading is a linear

activity of identifying the exact linguistic units.

Goodman (1996) argues that guessing and prediction

occur during reading instead of the precise process

of retrieving individual linguistic units, as

demonstrated in his example of a reader who made a

miscue by substituting the word ride with a more

familiar word run. This provides evidence that the

lexical knowledge the reader already had affected

the perception of the actual printed word, and this

indicates another type of cognitive process, i.e. the

top-down mode. The top-down or expectation-based

model emphasizes the salient role of schemata in

comprehension. This model relies heavily on schema

theory which posits that knowledge is stored in units

called schemata in the reader’s mind (Rumeralt,

1980). Each schema contains objects and actions

602

Kusumarasydati, . and Ramadhani, F.

An Overview of EFL Reading Comprehension.

DOI: 10.5220/0009913006020607

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Recent Innovations (ICRI 2018), pages 602-607

ISBN: 978-989-758-458-9

Copyright

c

2020 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

that relate to a particular type of knowledge, and a

huge collection of schemata are organized efficiently

in the mind for retrieval whenever necessary.

Anderson and Pearson (Anderson et all, 1990)

suggest that reading mainly involves an interaction

between the old knowledge stored in memory

(schemata) and the new messages in the text. The

reader comprehends successfully if s/he manages to

‘hook up’ the information learned from the text with

the prior knowledge that s/he has already possessed.

Studies involving verbal reports reveal that such

interplay between the text content and the reader’s

schemata occurs extensively during text processing

(Presley et all, 1995). However, it can be misleading

to argue that reading is strictly top-down and

requires the reader to simply relate the schemata and

the knowledge attained from the printed text. Studies

about eye movement during reading indicate that

“skilled readers fixate at least once on the majority

of words in a text. They do not skip a large number

of words, as the top-down view predicts, but instead

process the letters and words rather thoroughly”

(Treiman, 2001). Thus, the bottom-up processing is

not completely refutable as letter-by-letter and word-

by-word perceptions still occur while the reader is

trying to comprehend a piece of writing.

It is apparent that the bottom-up or top-down

model only can sufficiently provide explanation

about how the reading process works to attain

comprehension: both are necessary and operate

interactively in order to ensure thorough

comprehension (Alderson, 2000).

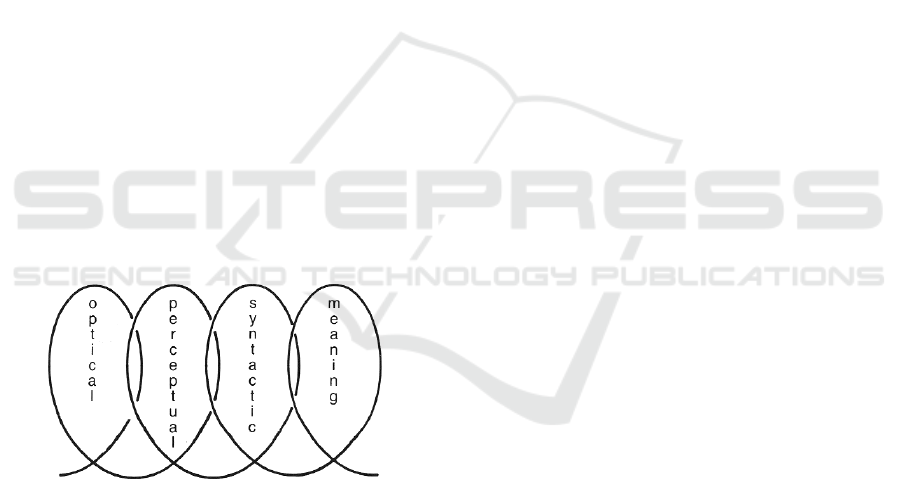

Fig. 1 Cyclical mode of linguistic processing during reading [8]

(Nutall, 1996). Several types of interactive model

have been proposed, such as the interactive-

activation model (McCelland, 1981) and the

interactive-compensatory model (Bernhardt, 2003),

but in spite of the different emphasis each puts they

all have a key feature: linguistic-based and the

knowledge-based processing works simultaneously.

The interactive model still recognizes the

hierarchical processing from the lowest linguistic

level to the highest, but the procedure goes in

cyclical movement instead of a serial one

(Goodman, 1976), which enables the reader to go

back and forth along these levels (Fig. 2).

Although this interactive reading process is

applicable universally in any reading, some

significant distinct features exist between L1 reading

and foreign language (FL) reading. It is essential that

these differences be taken into consideration when

one teaches reading so the next section will

elaborate this issue.

3 LITERARY REVIEW

3.1 Definitional Issues of Reading

Reading involves more than merely decoding

printed words in a particular passage. In addition to

this perceptual activity, reading also requires the

learners to perform psychological as well as social

activities (Paris et all, 1983; Bloome, 1984) in order

to comprehend the passage. There have been several

attempts to define this complex process, but the

basic concept of reading is perhaps outlined well by

the definition offered by Ruddell (1994): ‘a process

in which the reader constructs meaning while, or

after, interacting with text through the combination

of prior knowledge and previous experience,

information in text, the stance s/he takes in

relationship to the text, and immediate, remembered,

or anticipated social interactions and

communication” (p.415). Thus, reading

comprehension should be approached from the

cognitive view, according to which the reader

actively constructs meaning—instead of simply

extracting it—by activating schemata or knowledge

structures in his/her mind to relate the knowledge

that is already possessed to the new ideas stated in a

passage. This cognitive process results in unique

personal meaning as different readers have different

types and levels of knowledge about a certain topic

discussed in the passage. Furthermore, the meaning

is also socially constructed by taking into account

the reader’s knowledge, beliefs and attitudes which

are shaped by his/her social and cultural background

(Smagorinsky, 2001). It is vital, as a consequence,

that text interpretation involve the activation of

information shared by the members of the social

group purported by the text. To refine the

aforementioned definition, it is essential to examine

the basic concepts of reading comprehension

articulated by influential scholars who have

intensively examined it from the psycholinguistic

point of view, Frank Smith and Kenneth Goodman.

3.1.1 Frank Smith’s View of Reading

Smith (1971) admits that formulating a definition of

reading is a futile attempt as this word may mean

different things in various contexts, making it almost

An Overview of EFL Reading Comprehension

603

impossible to rely on only a single definition.

However, he proposes a model of reading that may

explain how the written input is processed in a

human’s mind and results in comprehension of ideas

held in that piece of writing. According to Smith’s

model, comprehension is viewed as the extraction of

meaning from a text, and can be defined as “the

reduction of uncertainty” (p. 185) at three levels:

letter identification, word identification, and

meaning identification. This model maintains that a

reader needs to identify a letter and distinguish it

from the other 25 letters. In other words, the reader

should be certain that what s/he perceives as h is

actually the letter h by recognizing its visual

features. If s/he is able to reduce the possibilities out

of the twenty six letters and is convinced that the

perceived letter is h, then comprehension is taking

place. This also applies to word identification, in

which the reader is supposed to identify a word by

reducing a myriad of possible existing words in a

language. For instance, s/he can confidently identify

the word horse as horse instead of house or hours.

Finally, the reduction of meaning also occurs at the

semantic level, where s/he is supposed to pick up the

most appropriate meaning of a word out of several

plausible meanings. Smith adds that the

comprehension process in reading is much more

complicated than the above description. The letter

identification in English, for example, does not

always proceed from left to right although reading

appears to be done in this direction. To illustrate, the

reader can find out how to read the letters h and o at

the beginning of a word and transform them to the

correct English sounds only by taking the letters that

follow them into account. The letters ho that precede

use would be pronounced differently from those that

come before the letters rse. It can be concluded that

letter identification actually goes bidirectionally,

from left to right and also the other way around.

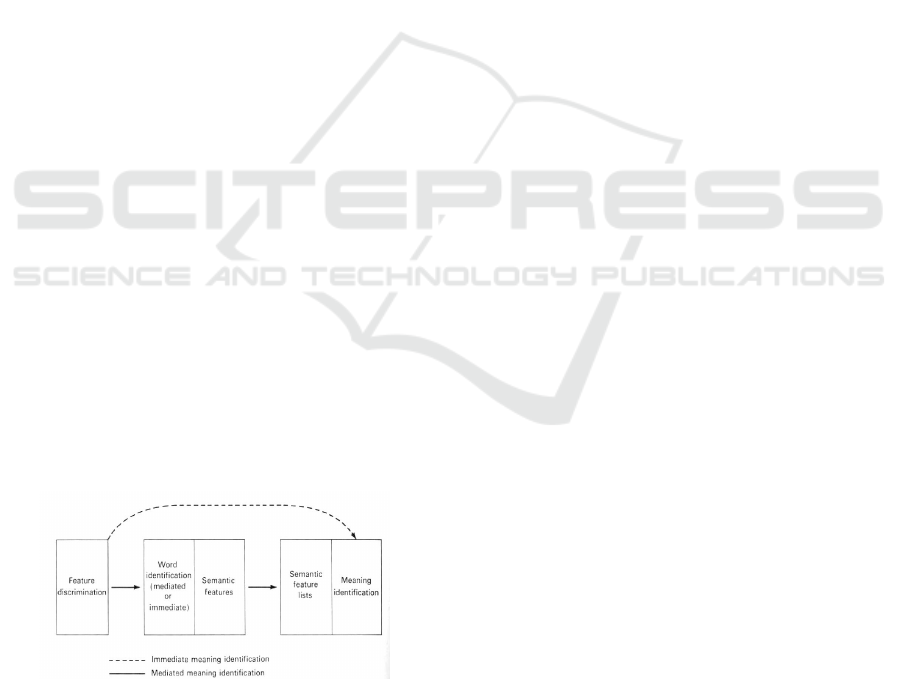

Fig.2 Immediate and Mediated Meaning Identification [6]

In spite of the aforementioned three levels that have

been identified in the model, it proposes that reading

comprehension is more complicated than the

execution of the serial process of identifying letters,

words and meanings. Smith distinguishes two ways

in which the identification takes place, namely

‘immediate’ and ‘mediated’. In the immediate

meaning identification, the reader recognizes the

features of the letters in print, and can instantly

understand the meaning of what s/he is perceiving.

On the other hand, the mediated meaning

identification needs a longer process. After the

reader successfully identifies the features of the

letters, s/he attempts to figure out the individual

words in order to understand the semantic features

of each word. From a list of these semantic features

s/he narrows down the meaning by eliminating the

alternatives so that s/he could eventually decide

which meaning is the most appropriate (Fig. 1).

Smith (1985) posits that every reader relies on both

types of meaning identification, but one is used in a

different condition from another. If s/he already has

non-visual information in the form of prior

knowledge, it is easier for him/her to understand the

meaning stated in the printed text and in this case

immediate meaning identification occurs. The

typical reading activity normally involves this sort of

meaning identification. However, when the previous

experience related to the issues discussed in the text

is absent on the part of the reader, comprehension is

impeded and this condition prompts the reader to

switch to the mediated meaning identification, in

which every individual word is retrieved and figured

out to enable easier identification of meaning. Thus,

reading comprehension in Smith’s model requires

both visual information from the text and non-visual

information in the form of his/her personal

experience, with meaning identification as its end.

3.1.2 Goodman’s View of Reading

Another cognitive view of reading comprehension is

that of Goodman (1976), who defines reading as

follows:

Reading is a perceptive language process. It is a

psycholinguistic process in that it starts with a

linguistic surface representation encoded by a writer

and ends with meaning which the reader constructs.

There is thus an essential interaction between

language and thought in reading. The writer encodes

thought as language and the reader decodes language

to thought (p. 12).

The key concept in his model is the construction

of meaning. Instead of merely getting the meaning

written in the text, the reader ‘interacts’ with the

writer by reconstructing the meaning which is

communicated and intended by the writer.

Goodman (1976) coined the term

‘psycholinguistic guessing game,’ which refers to a

mental process where, as the name suggests, the

reader deciphers information in the text and attempts

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

604

to make guesses based on the available cues by

making effective use of the knowledge of the world

and the linguistic one. The aforementioned

information is not confined to the printed letters

only, but also includes the syntactic and semantic

cues implicated in the text. To comprehend it, the

reader selects the most appropriate types of cues in

order to predict and anticipate ideas, then either

confirms or disconfirms the accuracy of the

prediction. If the prediction turns out to make sense,

s/he will proceed to the other ideas in the same

manner, but disconfirmation of the prediction will

produce miscues, or “errors” of comprehension. The

reader has the ability to monitor the miscues s/he

produces, and the awareness of such miscues leads

to the re-examination of the ideas by means of the

possible cues and prior knowledge to generation

other predictions. At the end of the cyclical process,

comprehension of the whole text can be attained.

Apparently Goodman’s view of reading

acknowledges the important role of both the visual

input from the text and the cognitive abilities of the

reader. His model, therefore, defines reading as the

process of meaning construction by integrating the

textual information and the reader’s knowledge.

The complicated process as explained above makes

the label of passive language skill for reading seem

to be a misnomer as the reader actually does not

passively decode written information in the text.

Reading is more appropriately called a receptive

skill than a passive one as the reader actively

constructs meaning while deciphering the printed

input (Smith, 1985; Barnet, 1989). This mental

process, as educators and researchers agree, operates

in a complex manner, involving a number of

different variables that interact with each other. The

rest of this paper discusses some issues relevant to

this concept.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Reading in L1 and Fl

Bernhardt (2003) emphasizes the distinct nature of

L1 reading and L2 reading for two reasons. First,

readers store different types of memory related to

languages, and this affects the cognitive processing

when they read a certain text. To illustrate, a Spanish

reader possesses visual and syntactic memory that

corresponds with the English text input due to the

same alphabetic system and the similar grammatical

rules between the two languages, but phonological

memory that does not because these languages do

not share the sounds. In the case of Indonesian

readers, the extent to which their memory matches

the English text input may even be lower as English

and Bahasa Indonesia or Javanese are only remotely

related: they share the alphabetical system but not

the phonological, lexical and syntactic ones. Thus,

the readers’ stored memory of sounds, words and

grammar might not match the input in the form of an

English text, demanding an extra effort to expend in

its processing.

The second difference relates to the

aforementioned social aspect of reading. It has been

argued that the meaning constructed while reading is

influenced to a certain degree by the readers’ social

experience and culture. Bernhardt (Bernandt, 2003)

provides an example of this phenomenon by

comparing the meaning of ‘breakfast’ as read by an

English and a Japanese

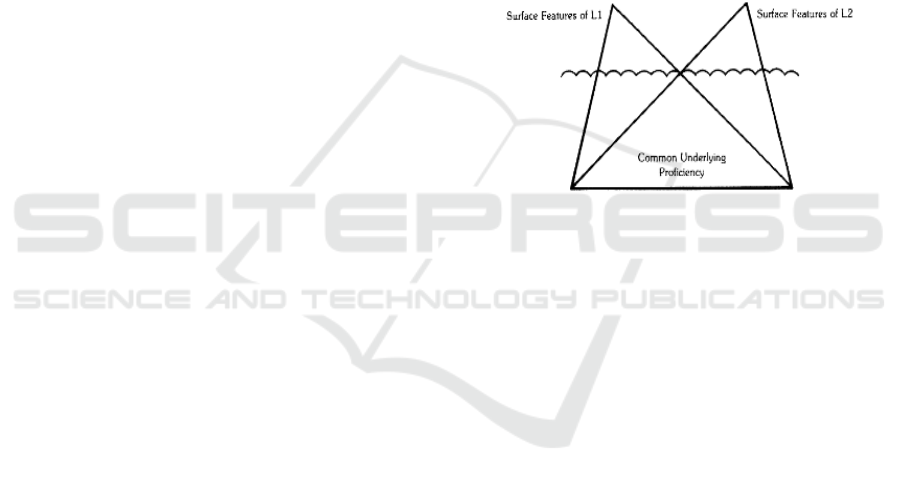

Fig. 3 Common Underlying Proficiency [25]

person. The English reader is very likely to have the

relevant information of a typical breakfast prepared

in a Western culture, but the Japanese reader

possibly does not possess the same semantic

concepts and thinks, instead, of a typical breakfast in

his/her own culture. Thus, although both readers can

recognize the meaning of the word, they may have

different memory representation associated to it.

As a matter of fact, the different cognitive

processing involved in reading texts in L1 and FL

has long invited controversy. To date the opinions

related to the influence of L1 on FL as far as reading

is concerned have been polarized in two different

hypotheses (Alderson, 1984). The first hypothesis,

known as the reading-universal hypothesis or the

linguistic interdependence hypothesis, states that

reading ability in the mother tongue is automatically

passed on FL reading, hence good readers in L1 are

assumed to read similarly well in FL as both are

considered to require the same processes. Common

Underlying Proficiency (Cummins, 1989) shared by

the L1 and other languages that the readers possess

facilitates the transfer of reading skills from L1 to

FL (Fig. 3).

An Overview of EFL Reading Comprehension

605

On the other hand, the short-circuit hypothesis [26]

or the linguistic threshold hypothesis asserts that

attaining a particular minimum standard of FL

proficiency is an essential prerequisite of such a

transfer to occur. Alderson (Alderson, 1984)

provides some empirical evidence that supports each

hypothesis and concludes that both L1 reading

ability and FL proficiency make equal contribution

to successful comprehension in FL, yet, he

emphasizes—at least tentatively—that the latter

seems to become a more dominant factor in the

cases of lower levels of FL, and encourages further

research. Since then, studies have been conducted to

respond to this call, resulting in mixed findings.

Some studies support the linguistic interdependence

hypothesis

(M. Danesi, 1988; Cumming et all, 1989;

Gholamain, 1999)

whereas others confirm both

hypotheses, highlighting the importance of L2

proficiency over L1 reading ability (Laufer, 1992;

Koda, 1993; Tailefer, 1996; Pugh, 1998, Schoonen

et all, 1998( The latter stance seems to make more

sense, as it takes into account all relevant factors in

foreign language reading, namely the strategies

applied in the L1 reading and the linguistic

competence in the FL, and explains the way they

interact while the readers are attempting to

apprehend the ideas in a passage. Successful

comprehension requires more than merely the

mastery of a reasonable amount of FL linguistic

knowledge; it also involves the application of the

appropriate L1 reading strategies to FL reading.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, it has been argued that reading

comprehension is the socio-cognitive process of

constructing meaning from a text. The process could

be bottom-up (from the smallest linguistic unit to the

largest), top-down (using background knowledge) or

interactive (both bottom-up and top-down).

According to the reading-universal hypothesis, good

reading ability in L1 transfers automatically to

reading in FL. However, the short-circuit hypothesis,

which requires the readers to reach the threshold

level of FL proficiency for such a transfer to occur,

seems to be more sensible.

The implications of this stance for reading

instructions are threefold. First, reading teachers

should ensure the learners’ FL proficiency passes the

threshold level to facilitate the learners’ reading

comprehension. The teachers should give sufficient

opportunity to the learners to enrich their vocabulary

and knowledge about grammar while the learners are

trying to make sense of the reading texts. Next, the

teachers should encourage the learners to construct

meaning, rather than getting meaning, from the text.

In doing so, the learners need to rely on their

cognitive ability as well as the social context where

reading comprehension is occurring. Finally, it is

better for the teachers to provide guidance about the

use of bottom-up and top-down processes in

interactive reading. For instance, the top-down

process is more suitable for texts which are

relatively easy to comprehend, but once the

comprehension is impeded by unknown words or

complicated sentence structures, the learners should

switch to the bottom-up process. By taking these

three points into consideration and applying them in

reading instructions, hopefully reading

comprehension becomes more effective for the EFL

learners.

REFERENCES

Alderson, C. 2000. Assessing Reading. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Alderson, J. C. 1984. "Reading: A Reading Problem or a

Language Problem?". In: J. C. Alderson and A. H.

Urquhart, Eds. Reading in a Foreign Language.

London: Longman, pp. 1-24.

Anderson, R.P. and P.D. Pearson. 1990. “A Schema-

theoretic View of Basic Processes in Reading

Comprehension,” In: P. L. Carrell, J. Devine and D. E.

Eskey, Eds. Interactive Approaches to Second

Language Reading. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Barnett, M. A. 1989. More than Meets the Eye: Foreign

Language Learner Reading, Theory and Practice.

Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall Regents.

Bernhardt, E. B. 1991. Reading Development in a Second

Language: Theoretical, Empirical, and Classroom

Perpectives. Norwood: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Bernhardt, E. B. 2003. "Challenges to Reading Research

from a Multilingual World." Reading Research

Quarterly, 38, pp. 112-117.

Bloome, D. and J. Green. 1984. Directions in the

Sociolinguistic Study of Reading. In: P. D. Pearson, R.

Barr, M. L. Kamil and P. Mosenthal, Eds. Handbook

of Reading Research. New York: Longman, pp. 395-

421.

Clarke, M. A. 1988. "The Short-circuit Hypothesis of ESL

Reading--or When Language Competence Interferes

with Reading Performance." In: P. L. Carrell, J.

Devine, and D. E. Eskey, Eds. Interactive Approaches

to Second Language Reading. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Cumming, A. Rebuffot, J. and M. Ledwell. 1989.

"Reading and Summarizing Challenging Texts in First

and Second Languages". Reading and Writing, 1, pp.

201-219.

Cummins, J. 1984. "Bilingualism and Special Education:

Program and Pedagogical Issues". Learning Disability

ICRI 2018 - International Conference Recent Innovation

606

Quarterly, 6, pp. 373-386.

Cummins, J. 1989. "Language and Literacy Acquisition in

Bilingual Contexts." Journal of Multilingual and

Multicultural Development, 10, pp. 17-31.

Danesi, M. 1988. "Mother-tongue Training in School as a

Determinant of Global Language Proficiency: A

Belgian Case Study". International Review of

Education, 34, pp. 439-454.

Dufva, M. and M. J. M. Voeten. 1999. "Native Language

Literacy and Phonological Memory as Prerequisites

for Learning English as a Foreign Language". Applied

Psycholinguistics, 20, pp. 329-349.

Gholamain, M. and E. Geva. 1999. "Orthographic and

Cognitive Factors in the Concurrent Development of

Basic Reading Skills in English and Persian".

Language Learning, 49, pp. 183-217.

Goodman, K. 1988. "The Reading Process". In: P. L.

Carrell, J. Devine, and D. E. Eskey, Eds. Interactive

Approaches to Second Language Reading. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Goodman, K. 1996. On Reading. Ontario: Scholastic.

Goodman, K. S. 1976. "Behind the Eye: What Happens in

Reading". In: H. Singer and M. R. Ruddell, Eds.

Theoretical Models and Processes in Reading.

Newark: International Reading Association, pp. 470-

496.

Gough, P. B. 1972. "One Second of Reading." In: J. F.

Kavanagh and I. G. Mattingly, Eds. Language by Ear

and Eye. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hardin, V.B. 2001. “Transfer and Variation in Cognitive

Reading Strategies of Latino Fourth-grade Students in

a Late-exit Bilingual Program”. Bilingual Research

Journal, 25, pp. 539-61.

Hoover, W.A. and P.B. Gough. 1990. “The Simple View

of Reading”. Reading and Writing, 2.

Jiang, B. and Kuehn. P. 2001. "Transfer in the Academic

Language Development of Post-secondary ESL

Students". Bilingual Research Journal, 25, pp. 653-

672.

Koda, K. 1993. "Transferred L1 Strategies and L2

Syntactic Structure in L2 Sentence Comprehension".

The Modern Language Journal, 77, pp. 490-500.

Lasagabaster, D. "The Threshold Hypothesis Applied to

Three Languages in Contact at School". International

Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1,

pp. 119-133.

Laufer, B. 1992. Reading in a Foreign Language: How

Does L2 Lexical Knowledge Interact with the Reader's

General Academic Ability. Journal of Research in

Reading, 15(2), 95-103.

McClelland, J.L. and D.E. Rumelhart. 1981. “An

Interactive Activation Model of Context Effects in

Letter Perception”. Psychological Review, 88, pp. 375-

407.

Meschyan, G. and A. Hernandez. 2002. "Is Native-

Language Decoding Skill Related to Second Language

Learning?". Journal of Educational Psychology, 94,

pp. 14-22.

Nuttall, C. 1996. Teaching Reading Skills in a Foreign

language

. London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Paris, S. G. M. Y. Lipson, and K. Wixson. 1983.

"Becoming a Strategic Reader". Contemporary

Educational Psychology, 8, pp. 293-316.

Pichette, F. Segalowitz, N. and K. Connors. 2003. "Impact

of Maintaining L1 Reading Skills on L2 Reading Skill

Development in Adults: Evidence from Speakers of

Serb-Croatian learning French". The Modern

Language Journal, 87, pp. 391-403.

Pressley, M. and P. Afflerbach, 1995. Verbal Protocols of

Reading: The Nature of Constructively Responsive

Reading. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ruddell, M. R. 1994. "Vocabulary Knowledge and

Comprehension: A Comprehension-process View of

Complex Literacy Relationships." In: R. B. Ruddell,

M. R. Ruddell, and H. Singer, Eds. Theoretical

Models and Processes of Reading. Newark:

International Reading Association.

Rumelhart, D. 1980. "Schemata: The Building Blocks of

Cognition". In: R. J. Spiro, B. C. Bruce, and W. F.

Brewer, Eds. Theoretical Issues in Reading

Comprehension: Perspectives from Cognitive

Psychology, Linguistics, Artificial Intelligence, and

Education. Hillsdale: Erlbaum Associates.

Schoonen, R. Hulstijn, J. and B. Bossers. 1998.

"Metacognitive and Language-Specific Knowledge in

Native and Foreign Language Reading

Comprehension: An Empirical Study among Dutch

Students in Grades 6, 8, and 10". Language Learning,

48, pp. 71-106.

Smagorinsky, P. 2001. "If Meaning Is Constructed, What's

It Made From? Toward a Cultural Theory of Reading".

Review of Educational Research, 71, pp. 133-169.

Smith, F. 1971. Understanding Reading: A

Psycholinguistic Analysis of Reading and Learning to

Read. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Smith, F. 1985. Reading. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Stanovich, K. E. 1980. "Toward an Interactive-

Compensatory Model of Individual Differences in the

Development of Reading Fluency". Reading Research

Quarterly, 16, pp. 32-71.

Taillefer, G. F. 1996. "L2 Reading Ability: Further Insight

into the Short-Circuit Hypothesis". The Modern

Language Journal, 80, pp. 461-477.

Taillefer, H. and T. Pugh. 1998. "Strategies for

Professionals Reading in L1 and L2". Journal of

Research in Reading, 21, pp. 96-108.

Treiman, R. 2001. "Reading." In: M. Aronoff and J. Rees-

Miller, Eds. Handbook of Linguistics. Oxford:

Blackwell, pp. 664-672.

van Gelderen, A. Schoonen, R. de Glopper, K. Hulstijn, J.

Simis, A. Snellings, P.and M. Stevenson. 2004.

"Linguistic Knowledge, Processing Speed, and

Metacognitive Knowledge in First- and Second-

Language Reading Comprehension: A Componential

Analysis". Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, pp.

19-30.

An Overview of EFL Reading Comprehension

607