Organizing Organic Vegetables Farming in Narrow Land: A Study o

f

Social Entrepreneurship Community

Margunani Margunani, Etty Soesilowati and Inaya Sari Melati

Universitas Negeri Semarang, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia

Keywords: empowerment, food empowerment, organic vegetables, technology.

Abstract:

This study aims at organizing a family-based food empowerment; applying technology for organic vegetable

farming in narrow land; and improving technical, price, and economic efficiency on production factors. The

subjects of this study are housewives in Gunungpati, Semarang by employing an exploratory sequential mixed

methods research design. The technology used in this activity is quite unique since the organic vegetables are

cultivated using polybags considered as a pot or a place to grow vegetables. Treatments for disease control

and pest vegetables harness the local herbs as an environmentally friendly medicine. The results show that

organic vegetables produced by a housewives group meet the needs of food consumption, especially on

vegetables. Vegetables cultivation sustainably maintains the family’s food self-sufficiency and lead to semi-

commercial needs of the surrounding communities. Housewives community are pleased, satisfaction and be-

come more productive in terms of economic matters.

1 INTRODUCTION

The demand for organic produce in developed

countries keeps growing year by year (Wier &

Calverley, 2002; Dangour et al., 2009; Detman &

Dimitri, 2010). Take organic vegetables as examples.

The growing population of middle class is taking the

lead in purchasing them. They are even willing to

offer more money as long as they obtain goods which

are not only healthier but also environmentally-

friendly. Increased awareness of a better place to live,

a healthy lifestyle, supports from government

policies, food industries, and markets taking up 50%

of organic products, high prices among consumers,

“organic” labelling, and adamant national

campaigns on organic farming are the main factors in

driving the demand for organic vegetables.

Furthermore, farmers apply farming conservation

in an organic manner due to matters such as

environment, social economy, independence, and

health (Baudron et al., 2012). In Indonesia, organic

farming has been developing for about five years

which is expected to gain more profitable outcomes.

However, they turn out to be not fulfilling, especially

for those who do not own adequate farming land,

because of unpredictable all year round rainfall levels

(2016-2017) resulting in damaged crops. One

apparent cause for this to happen is the way they

manage the cultivation which is still conventional. A

number of emerging farming development

technologies and information cannot easily reach

them and change their mind-sets and styles in

farming. This is where a social entrepreneur comes to

the rescue to undergo systemic changes on social

environment by encouraging social changes

(Nicholls, 2006).

Gunungpati, Semarang, Central Java, is one of

regions famous for producing durians and rambutans.

Besides, it is also well-known for other nature

potentials, such as tourism spots like Goa Kero and

Sendang Abimanyu, fishing spots (Ngrembel Asri,

Dewandaru, and Pagersalam), and Jatibarang Lake.

Grounded on its landscape characteristic, Gunungpati

consists of impressive natural resources, such as

geographic location, climate, soil and topography,

water, biota (flora and fauna), sound, scenery,

settlement patterns, and architectural structures. With

a good and proper policy and management, such

Margunani, M., Soesilowati, E. and Melati, I.

Organizing Organic Vegetables Farming in Narrow Land: A Study of Social Entrepreneurship Community.

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Economic Education and Entrepreneurship (ICEEE 2017), pages 429-435

ISBN: 978-989-758-308-7

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

429

promising nature potentials will lead to an abundant

supply of quality products.

The growth and development in Gunungpati as

the green belt of Semarang is closely related to the

aspect of social economy of the people who earn their

living from growing fruit and laboring as their side

jobs. The latter is necessary for them to meet their

daily needs as growing fruit is seasonal. Most of them

are not intensive farmers. They grow fruit for their

own consumption and sell the rest of it. Be-sides, they

own limited size of farming land. Cultivating organic

vegetables in narrow land around their houses can be

an alternative way that should be taken into

consideration, for it can not only fulfil their needs on

hygienic food but also preserve the nature. A model

of efficient and effective cultivation is required for

this to happen.

Unfortunately, filed based observation indicates

that there are some issues which are likely to be

obstacles to the people of Gunungpati’s real income

when starting a business of organic vegetables

cultivation, namely: (2) a small number of people

who are into cultivating them; (2) inadequate farming

land; (3) insufficient technology to function narrow

land; and (4) the people’s lack of knowledge on the

cultivation of organic vegetables. The state is not only

the responsibility of the government but also all social

elements. A harmonized cooperation among the

government, farmers, and intellectuals must occur in

order to enhance the productivity of farming

products, especially the organic ones which are not

only environmentally-friendly but also safe for daily

consumption.

Pioneering organic vegetable business is an in-

novation that can be done to increase family income.

This refers to the research results of Ulfah & De-

wanto (2014) which is found that if the producer

developed a product innovation follow the rapidly

changing world, make the consumer give more

interest in to the local product. That indication could

build an engagement between local producers and

consumers. Nevertheless, creating business

innovation in the form of organic vegetable farming

is not the only solution in empowering the community

for economic strengthening. Innovation does not

mean anything without the competence to manage the

business. Loh & Dahesihsari (2013) found that

entrepreneurial quality and business success depend

heavily on personal characteristics of business people

(in this study are women), not on any formal

education system or training. The study also found

that many women were able to develop a strategy of

anticipating a strong business failure. As a

consequence, they are able to develop despite facing

many social, cultural and political barriers.

This research further examines: (1) how family-

based food security model is; and (2) how the cost and

benefit of cultivating organic vegetables in narrow

land are. The research also aims at providing short-

term benefits, namely (1) as an activity for

housewives and the members of local youth

organizations not only to be entrepreneurs but also to

meet daily needs on food, (2) making use of vacant

land in the neighbourhood, and (3) as a piloting

project of cultivating hygienic and efficient organic

vegetables. The long-term one is for how this farming

can be used as a piloting project associated with

integrated family-based conservation and security

food pro-gram before applied widely and also as a

chance to export organic vegetables to international

markets.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Conventional farming refers to a farming sys-tem

making use of synthetic chemical fertilizers and

pesticides and other materials to manage weeds and

pests leading to potential risk to humans and other life

forms and unwanted side effects to the environment,

such as pollution, residual pesticides on food, health

issues, loss of useful wildlife, growing resistance of

insects and pathogens, and pest resurgence (Arya et

al., 1996). This farming method can be developed

further provided that farmers are in possession of a

large amount of capital and able to predict the weather

and prices to cover production cost. Agribusiness as

a commercial farming invasion may grow as what

occurs in Zimbabwe (Kinsey, 2010). On the other

hand, the use of synthetic fertilizers poses a likely

threat to soil fertility. In fact, they can enhance the

production of nutrients needed for soil fertility, yet

they may also disrupt absorption and balance of other

nutrients in the soil and reduce the growth of soil

microbes causing the production of humus to

suppress (Glass, 1987). To lessen these hazards, an

alternative technology-based organic farming in the

form of recycling soil nutrients by utilizing organic

residues as fertilizers and nitrogen fixation,

employing natural enemies and cutting down

chemical substances needs to be developed.

Organic vegetables farming is an organic

agriculture which is supposed to be managed well and

intensively in the form of a firm with a complete

structure organization and transparent job

descriptions in order that its fixed and variable costs

function effectively and optimally and guarantee

ICEEE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Economic Education and Entrepreneurship

430

products with good quality, quantity, and continuity.

The seeds in organic vegetables farming are not

derived from genetic engineering or genetically

modified organism (GMO), but they are gained from

organic farming plantation and do not apply synthetic

fertilizers and phytohormones. Soil fertility security

is practiced through providing organic and natural

fertilizers, plant residues, and legume rotation and

avoiding the use of synthetic and chemical pesticides

while weeds and pests are controlled manually with

natural pesticides and agents and plant rotation.

Synthetic phytohormones and additive substances on

fodder and manure are also prevented from use. Post-

harvest and food preservation are handled in natural

manners.

Nutrient control technology on organic farming is

practiced though recycling plant nutrients naturally to

enhance biological, physical, and chemical soil

fertility. Macro and micro nutrients taken away

during harvest are brought back by adding organic

fertilizers and plant residues periodically into the soil

in the form of either green manure or compost. It is

highly recommended that organic fertilizers are

obtained from organic substances, such as composted

manure, legume residues, and hedgerow cuts organic

waste, as well as tithonian diver’s folia as a green

manure. The applied manure should not be taken from

live stocks managed in factory farming. The existing

is-sue of narrow land in fact occurs due to planting

pat-terns with soil as its direct media. Potting system

and polybag nursery can be silver bullets to over-

come this issue so that farming activities continue to

thrive.

3 METHODS

The research is conducted in Gunungpati consisting

of 12 villages with 89 hamlets (RW) and 418

neighbourhoods (RT). The people who have already

cultivated organic vegetables on a daily basis for

more than two years and founded a community, Fe-

male Farmers Organization (KWT), called Sri Rejeki,

are those from RW 3 of Plalangan with 24 house-

wives as the members.

This research is specific, meaning that the subject

is family groups, and holistic, implying that it covers

the aspects of both agricultural technology and

agricultural economics. Both the researcher and the

subject are interactively involved at a particular time

and context. Regarding the distinctiveness of the

subjects, the objects, and the characteristics of the

research, it employs exploratory sequential mixed

methods, a mixed research method pertaining to a

sequence of activities experienced by the researcher

to gather both quantitative and qualitative data

(Creswell et al., 2010).

In this research, qualitative data collection is

gathered prior to the quantitative ones. It is essential

to do so, for the purpose of the research is, at first, to

explore the issues being examined, and then proceed

with quantitative data which can be utilized to

analyze larger samples, so the results of the research

can be commended to a population (Creswell et al.,

2010). More specifically, the goal of the use of

qualitative (Bogdan and Biklen, 1998) and

naturalistic re-search method (Kuncoro, 2007) is to

observe a natural phenomenon without any

manipulation in a con-text of entity. With this

approach, the researcher is required to apply

inductive procedures to describe the phenomenon

with a person as the main instrument. Quantitative

method, on the other hand, is in-tended to expose

nutrient content of a medium and a plant and to

calculate the degree of technical, price, and economic

efficiency, and the cost and benefit of cultivating

organic vegetables.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Family-Based Food Security Model

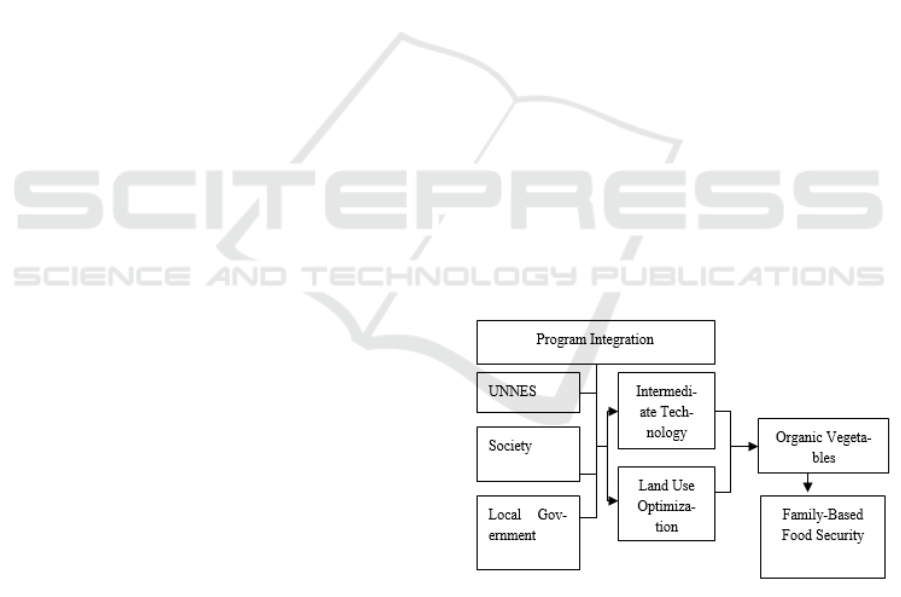

Based on theoretical analysis, family-based food

security model is formulated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Theoretical model of family-based food security

through the cultivation of organic vegetables in narrow

land.

This model is tested in the field to be further

evaluated and perfected with some inputs and

revisions from experts.

Organizing Organic Vegetables Farming in Narrow Land: A Study of Social Entrepreneurship Community

431

4.2 Cultivation of Organic Vegetables

in Narrow Land

Farming organic vegetables in narrow land in the area

of the research makes use of the courtyard and the

yard of a house, and the roadsides which certainly do

not hinder traffic. The cultivation also exploits

domestic waste, such as plastic packaging of mineral

water, frying oil, and detergent, paint cans, used

buckets and gutters, and other used materials. Tiny

size ones are functioned as the substitute of polybags

for seedlings. More than one liter/kg size of used

materials is used to cultivate organic vegetables and

are placed in every vacant nook and cranny of the

yard.

The vegetables are planted one by one in the

media, such as used paint cans, buckets, and plastic

packaging of frying oil holed at the bottom part for

water absorption. Approximately two meter long

gutters are used to plant vegetables placed in a row.

Used plastic is to be recycled, but it can also benefit

farmers with an issue of narrow land.

The members of KWT Sri Rejeki also belong to

Family Welfare Movement (PKK) of small groups of

ten families (Dasa Wisma), RT, and RW. Their effort

to undergo family food security through cultivating

organic vegetables in narrow land is supported by

their husbands, children, and parents. Besides, they

also provide treatment of the plants, control pests

naturally by taking advantage of local potentials, and

market the products after harvest if some are left after

meeting their family’s daily consumption. Husbands

play roles in preparing the media and plants’ sitting

places, and making bamboo hydroponic kit to show

their supports whereas children and parents deal with

the treatment and harvest. Post-harvest handling

includes sorting and grouping based on size and

standard to ease the process of marketing the

products.

4.3 Food Security of Organic

Vegetables

Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) in World

Food Summit of 1996 defines food security as

follows: “food security exists when all people, at all

times, have physical and economic access to

sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their

dietary needs and food preferences for an active and

healthy life.” Based on the definition, a country is not

considered having sustainable food security if its

citizens happen to be in famine and lack of nutrition.

Thus, food security is any country’s mission, for ac-

cess to food is human’s right and must be guaranteed

by the country. One of many efforts a country can

implement is to provide access to food for the poor in

order that they can lead productive life to raise the

state of their economic status. Food security is also

required for the purpose of growing healthy and

quality human resources to increase productivity and

national competitiveness and security.

Table 1: The Flow of marketing of organic vegetables in

narrow land in Gunungpati, Semarang.

No Marketing Pattern Total Percentage

1. Farmers Æ Consumers 23 95.83 %

2. Farmers Æ Sellers Æ

Consumers

1

4.17 %

3. Farmers Æ Collector

sellers Æ Sellers Æ

Consumers

0

0

Total: 24 100 %

Farming production of vegetables is seasonal and

requires particular location. The products are

distributed through marketing to consumers. The flow

of marketing used by the farmers of organic

vegetables in Gunungpati, Semarang, is through

direct marketing system, from the farmers to

consumers (95.83%). Marketing efficiency is

accomplished by analyzing the marketing flow. There

are two patterns in marketing organic vegetables in

Gunungpati. In general, the pattern is where the

farmers market the products to consumer’s first-hand.

It is a definitely efficient way of marketing, for the

farmers can savor all marketing profit margin for

themselves. It is in accord with Soekartawi (1989)

who argues that percentage of price margin paid by

consumers and producers are not too high. The

efficiency supports food security in Gunungpati in

particular. Similarly, Baipheti & Jacobs (2009) in

their research assert that farming contribution is

subsistent to food security in South Africa. In

addition, Ahmed & Lorica’s re-search findings

(2002) reveal that aquaculture handled domestically

improves food security in Asia.

Organic vegetables in narrow land produced in

Gunungpati are subsistent, which means that the

farmers cultivate them to meet their daily needs, and

market the rest if any. If one seeks for polybag plants,

they will trade them. Thus, they contribute a great

deal in providing nutritious, healthy, and safe

vegetables for their family. Moreover, the subsistent

characteristic also raises family’s income. Davidova

et al., (2012) in their research conducted in European

Union support this.

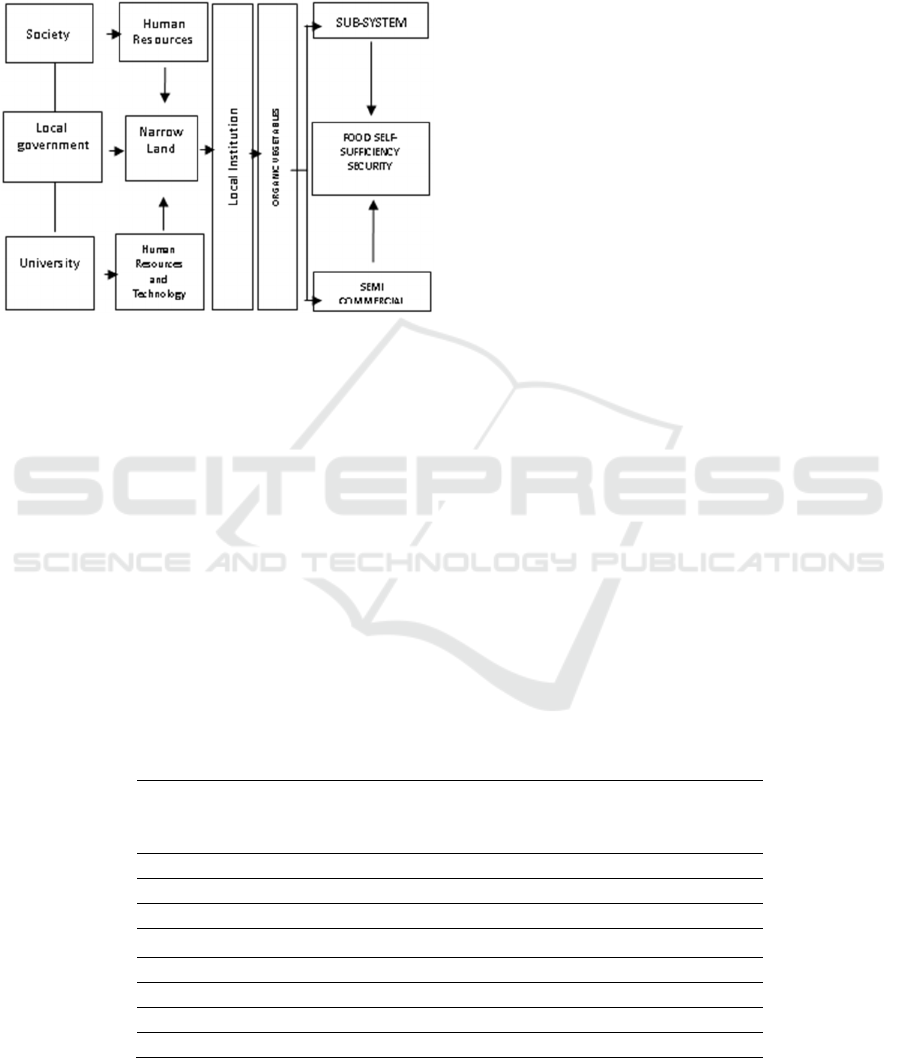

The result of discussion by the research team,

experts, and farmers concludes that family-based

food security model and the use of narrow land

generated based on empirical study in Plalangan is

further developed to be gradually disseminated to

ICEEE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Economic Education and Entrepreneurship

432

other villages or larger society. The model of family-

based food security through cultivation of organic

vegetables in narrow land which has been developed

and gains inputs from experts can is presented in this

following figure.

Figure 2: Empirical model of family-based food security

through cultivation of organic vegetables in narrow land

model.

This improvement model will be applied to

conduct dissemination of the implementation of

family-based food security through cultivation of

organic vegetables in narrow land in defined loci in

all villages in Gunungpati, Semarang.

4.4 Cost and Benefit of Family-Based

Food Security through Cultivation

of Organic Vegetables in Narrow

Land

Cost Benefit Analysis is a technique of analyzing cost

and benefit involving estimation and evaluating

benefit associated with alternative acts which will be

performed (Schniederjans; Hamaker; and

Schniederjans, 2004). Cost Benefit Analysis is

employed to predict loss and profit of a program. It

calculates cost and benefit obtained from carrying out

the program. Furthermore, it can be used to detect

how good and hazardous a program is. By including

profit and social cost, it can function as a firm basis

to determine decision making or funding and assure

investors as donators of a program, in this case the

farmers of organic vegetables, to come to a decision

whether to run the business or not.

Data in the field indicate that fixed cost and

variable cost needed by the farmers to cultivate

organic vegetables are relatively low. They will only

bear fixed cost if they provide hydroponic kits for

creeping plants on their own. Based on information

from the farmers of organic vegetables in

Gunungpati, Semarang, the fixed cost of the kit is

Rp.150,000.- to Rp.200,000.- depending on the

width, and there are only four farmers using them. As

mentioned before, the kit will come in handy for

certain vegetables requiring media for them to creep,

such as chayote, Chinese okra, and bitter melon.

Variable cost, on the other hand, covers the purchase

of seeds and planting media. However, not all farmers

buy planting media. Most of them take the ad-vantage

of used cans and common soil as planting media.

Land, manure, pesticides, and irrigation practically do

not require a lot of money since the land used is

privately-owned, the pesticides are self-made, and the

irrigation is from their own well.

Table 2: The cost of production of organic vegetables.

No

Kinds of

Farming Means

Farmers Total Price

Total

Cost

Fixed Cost

1. Hydroponic Kit 4 1 Rp. 150,000,- Rp. 600,000.-

Variable Cost

1.

Seeds

24 4 Rp. 3,000,- Rp. 288,000.-

2. Manure 24 0 0 Rp. 0.-

3. Husk 12 1 Rp. 5,000,- Rp. 60,000.-

4. Polybags 12 40 Rp. 250,- Rp. 120,000.-

Total Cost Rp. 1,068,000.-

Source: Analyzed data

Organizing Organic Vegetables Farming in Narrow Land: A Study of Social Entrepreneurship Community

433

Benefits in Cost Benefit Analysis are both

tangible and non-tangible. The former is income

gained by the farmers from selling organic vegetables

while the latter is a way for them who mostly are

housewives and teenagers to spend their spare or non-

productive time doing something useful, in this case

farming, so, even without cost, they benefit from what

they do such as producing organic vegetables on a

daily basis.

Basically, a business is worth running provided

that the average return compared to the total cost is

bigger than 1 as the higher a ratio of a business is, the

higher the profit will be. According to cost and

tangible benefit, the ratio of benefit and cost in

cultivating organic vegetables is Rp. 1,381,000: Rp.

1,068,000 Thus, the ratio is 1.29 (> 1) indicating that

this business is indeed worth running.

Table 3: Income of organic vegetables in Gunungpati.

Source: Analyzed data

5 CONCLUSIONS

Cultivation of organic vegetables in narrow land

intended to provide activities for society for the

purpose of accomplishing family-based food security

is able to accommodate local wisdom of the people in

Plalangan, Gunungpati by applying family-based

food security model which is still required to be ana-

lyzed further. Donation from 24 organic vegetable

farmer families in Gunungpati as many as 2892.2

kilograms of organic vegetables by making use of

narrow land in the yard of their houses is proven to be

able to meet FAO recommendation standard in

consuming vegetables in big families as many as

144.6 kg/capita/year. Technology of cultivation of

organic vegetables in narrow land which is

environmentally-friendly supports conservation

movement by reusing waste for planting media and

refraining from employing chemical substances

during production process. According to the ratio of

cost and benefit which is higher than 1, it can be

concluded that economically, cultivation of organic

vegetables is worth running as a potential business to

raise the in-come of organic vegetable farmers in

Plalangan, Gunungpati.

The implication in this research is that the

dissemination of innovation cannot be done with one-

time socialization activity, but must be done

continuously to the community, to internalize the

productive and innovative mind-set in running the

business. The recommended follow-up study to

complement and refine the results of this study is re-

search related to the utilization of waste for organic

vegetable planting medium.

No

Kinds of

Vegetables

Farmers Harvest (kg)/bln Price/kg Income

1. Bok cho

y

24 24 x 5 k

g

= 120 k

g

R

p

. 5,000.- R

p

. 600,000.-

2. Lee

k

22 22 x 0.5 = 11 k

g

R

p

. 6,000.- R

p

. 66,000.-

3. Water spinach 8 8 x 1 kg = 8 kg Rp. 3,000.- Rp. 24,000.-

4. Choy su

m

8 8 x 0.5 = 4 kg Rp. 5,000.- Rp. 20,000.-

5. Spinach 10 10 x 1 kg = 10 kg Rp. 3,000.- Rp. 30,000.-

6. Cosmos 6 6 x 1 k

g

= 6 k

g

R

p

. 2,500.- R

p

. 15,000.-

7. Lemon basil 5 5 x 0.2 k

g

= 1 k

g

R

p

. 7,000.- R

p

. 7,000.-

8. Celer

y

5 5 x 0.2 k

g

= 1 k

g

R

p

. 6,000.- R

p

. 6,000.-

9. Garlic chives 20 20 x 1 kg = 20 kg Rp. 4,000.- Rp. 4,000.-

10. Lettuce 2 2 x 1 kg = 2 kg Rp. 10,000.- Rp. 20,000.-

11. Cauliflowe

r

1 0 Rp. 10,000.- 0

12. Chili 22 22 x 0.1 k

g

= 2.2 k

g

R

p

. 20,000.- R

p

. 44,000.-

13. Broad beans 2 2 x 5 k

g

= 10 k

g

R

p

. 5,000.- R

p

.50,000.-

14. Peas 0 0 Rp. 20,000.- 0

15. Winged bean 2 2 x 2 kg = 4 kg Rp. 5,000.- Rp. 20,000.-

16. Tomato 20 20 x 0.5 kg = 10 kg Rp. 7,500.- Rp. 75,000.-

17. Lon

g

beans 0 0 R

p

. 6,000.- 0

18. E

ggp

lant 20 20 x 1 k

g

= 20 k

g

R

p

.5,000.- R

p

. 100,000.-

19. Bitter melon 4 4 x 10 k

g

= 40 k

g

R

p

.5,000.- R

p

. 200,000.-

20. Cucumbe

r

2 2 x 10 kg = 20 kg Rp.5,000.- Rp. 100,000.-

21. Rhizome 18 0 0 0

Total: 289.2 kg Rp.1,381,000.-

ICEEE 2017 - 2nd International Conference on Economic Education and Entrepreneurship

434

REFERENCES

Ahmed, M., Lorica, M. H., 2002. Improving Developing

Country Food Security through Aquaculture

Development-Lessons from Asia. Food Policy, Volume

27, Issue 2, pp.125-141, doi:

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-9192 (02)00007-6

Arya, N., Wirawan, G., Temaja, G., Susanta, G., K.Ohsawa

1996. Farming System and Inventory of Mayor Disease

of Vegetable in Highland Growing Area Candikuning

of Bali. In Resort of Integrated Research on Sustainable

Highland and Upland Agriculture System in Indonesia.

Baipheti, M. N., Jacobs, P. T., 2009. The Contribution of

Subsistence Farming To Food Security in South Africa.

Research in Agricultural and Applied Economics,

Volume 48, Issue 4, Pp. 459-482. Downloaded On

May, 28 2017 At 11:15 Am From

Http://Purl.Umn.Edu/58216.

Baudron, F., Andersson, J. A., Corbeels, M., Giller, K. E.,

2012. Failing To Yield? Ploughs, Conservation

Agriculture And The Problem Of Agricultural

Intensification: An Example From The Zambezi Valley,

Zimbabwe. Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 48,

No. 3, 21.

Bogdan, R. C., Biklen, 1998. Qualitative Research for

Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods,

Boston London, Allyn and Bacon.

Creswell. et al. (2010). Mapping the Developing Landscape

of Mixed Methods Research in Tashakkori, Abbas and

Teddlie, Charles (Ed.), “Handbook of Mixed Methods

in Social & Behavioral Research.” Sage Publications,

Inc. 2455 Teller Road, Thousand Oaks California

91320. 204-205.

Dangour et al. 2009. Nutritional Quality of Organic Foods:

A Systematic Review. The American Journal of

Clinical Nutrition, Volume 90, No. 3, Pp. 680-685.

Doi:10.3945/Ajcn.2009.2804

Davidova, S. et al. 2012. Subsistence Farming, Incomes,

and Agricultural Livelihoods in the New Member

States of the European Union. Environment And

Planning C: Politics And Space, Volume 30, Issue 2,

Pp. 209-227.

Dettman, R.L., Dimitri, C. 2010. Who's Buying Organic

Vegetables? Demographic Characteristics of Us

Consumers. Journal of Food Marketing, Volume 16,

2009, Issue 1. Down-loaded On May, 28 2017 at 10:38

Am from

Http://Dx.Doi.Org/10.1080/10454440903415709

Glass, N. 1987. Traditional and Modern Crop Protection in

Perspective. Bioscience

Kinsey, B. H. 2010. Who Went Where And Why: Patterns

And Consequences Of Displacement In Rural

Zimbabwe After February 2000. Journal Of Southern

African Studied, Volume 36, Number 2, 23.

Kuncoro, M. 2007. Metode Kuantitatif, Yogyakarta, UPP

STIM YKPN

Loh, J.M.I, Dahesihsari, R. 2013. Resilience and Economic

Empowerment: A Qualitative Investigation of

Entrepreneurial Indonesian Women. Journal of

Enterprising Culture. Volume 21, Issue 01, March

2013. pp. 107-121.

https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218495813500052

Nicholls, A. 2006. Social Entrepreneurship, New Model of

Sustainable Social Change

. United Kingdom: Oxford

University Press.

Scniederjans, M.J., Hamaker, J.L., & Scniederjans, A.M.

2010. Information Technology In-vestment: Decision-

Making Methodology (2nd Ed.). Singapore: World

Scientific Publishing.

Soekartawi. 1994. Teori Ekonomi Produksi, Jakarta, Pt

Raja Grafindo.

Ulfah, W.N., Dhewanto, W. (2014). Model in Generating

Social Innovation Process: Case Study in Indonesian

Community-Based Entrepreneurship. Full paper

proceeding TMBER-2014, Volume 1, pp. 168-175.

Wier, M., Calverley, C. (2002). Market Potential for

Organic Foods in Europe. British Food Journal,

Volume 104, Issue 1, pp.45-62, doi:

10.1108/00070700210418749

Organizing Organic Vegetables Farming in Narrow Land: A Study of Social Entrepreneurship Community

435