Empowering Capability for Innovation in IT Organizations

A Confluence of Knowledge for Continual Organizational Learning

Nabil Georges Badr

Business Administration, Grenoble Graduate School of Business, Grenoble, France

Keywords: Knowledge Transfer, Knowledge Acquisition, Technology Innovation Integration, IT Organizational

Learning.

Abstract: In IT based business model innovations, emerging technologies introduce disruption into processes and

organizational capabilities that could be difficult to overcome. IT services organizations must maintain their

IT capabilities of innovation integration in order to exploit it internally and for their customers. Using the

literature on resource based views as a grounding for organizational capabilities, this paper introduces a model

of continual organizational learning that empowers IT organizations for innovation integration. Through in-

depth case studies conducted at IT services companies, this exploratory research identifies mechanisms of

knowledge management are required to transform IT organizations to a lever rather than a barrier to

integrating innovation based on emerging technologies. The study succinctly presents the convergence of

knowledge assets through a cyclic process that empowers IT organization to embrace innovation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Companies are in the process of implementing

emerging technologies in IT (EIT), however, they

have reached varying stages of implementation.

Emerging technologies in IT are technologies such as

cloud, business automation and customer facing

innovations that have the potential to innovate the

way business is conducted translating into increased

value propositions to customers internal and/or

external to the firm.

The disruption introduced by emerging IT into the

existing infrastructure (Dan and Chang Chieh, 2010)

drives change into the IT organization (Tushman and

Anderson, 1986) requiring capabilities that are

required to dynamically adapt through the proficient

collaboration of people, processes and technology

(Mocker and Teubner, 2005). Trials in

operationalizing innovation (i.e. advancing new

technology from the lab to operations) affect the

ability of IT organizations to implement and support

these technologies. Hence, successful innovations

based on IT depend greatly on the combination of the

technology, the organization’s technical expertise,

and the organization’s ability to make effective use of

the new capabilities. In a dynamic competitive

environment, this is a clear challenge for the IT

operation consisting of both tacit (knowledge and

management competence) and explicit elements

(operational procedures and standards) which

translate to business performance metrics that could

be measured and reported by IT practitioners through

service management metrics specifically service

continuity.

Rapid change in EIT causes problems for IT

managers as they try to integrate these technologies

into an existing environment. Inevitably, this is a

drain on the resources that support the technology

deployments (Benamati and Lederer, 2010). The

challenges facing IT organization are hence elevated

to a level at which mechanisms that were effective a

few years ago have to be significantly overhauled.

These challenges are mostly linked to conflicting

priorities, integration issues, the availability of the

knowledge/skills required, and inadequate

infrastructure capabilities. Sometimes

insurmountable these challenges leave the firm

incapable to incorporate emerging information

technologies into their business model. In practitioner

circles, IT organizations are perceived as a hindrance

rather than an enabler to innovation.

The paper treats these challenges in the context of

IT organizations of IT services companies. For these

companies, emerging IT is not just a tool to support

business processes or to enable business model

innovation, but for both. These organizations are

Badr N.

Empowering Capability for Innovation in IT Organizations - A Confluence of Knowledge for Continual Organizational Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0006482000170028

In Proceedings of the 9th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management (KMIS 2017), pages 17-28

ISBN: 978-989-758-273-8

Copyright

c

2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

often asked to be the internal IT provider for the

internal customers (i.e. employees) and external

solutions and service providers for IT clients (i.e.

customers). What mechanisms of knowledge

management are required to transform IT

organizations to a lever rather than a barrier to

integrating innovation based on emerging

technologies?

2 BACKGROUND

When innovating a business model, IT leadership and

IT organizations, endure multi-dimensional

challenges, especially in IT services companies.

These IT organizations must participate in the success

of their host companies in an effort to lead IT based

innovation, internally and externally. IT

organizations in IT service companies have two

customers: IT is not only a cornerstone for the internal

business model with internal users of the company,

but also the core business in providing customer

facing services (Keel et al, 2007). This puts a burden

on the IT organization stretching its abilities to cover

users’ issues internal and external to the company

context with a persisting conundrum of providing a

reliable service to existing customers or creating new

customer through innovation (Berthon et al, 1999).

For instance, obstacles to knowledge acquisition and

training demands, product procurement dilemmas,

implementation and support prevail (Edwards and

Peppard, 1997).

2.1 Organizational Capability

Largely, IT organizational capabilities have received

a fair share of attention in various context. IS research

on resource based views (RBV) delineates resources

as physical capital (e.g. property, plant, etc.), human

capital (e.g. people, experience, relationships, etc.)

and organizational capital (e.g. organizational

structure and processes, etc.) (Barney, 1991).

Although resources and capabilities may be

considered part of a firm’s total assets, a capability is

the organizational ability to coordinate a set of

resources (human, financial, organizational or data,

etc.) to create a certain outcome (Grant, 1991).

Closer to the technology implementation

function, IT capability was described as the ability to

diffuse or support a wide variety of hardware and

software (Byrd and Turner, 2000); ultimately using

enterprise management systems of IT integration

(Galliers and Leidner, 2014), for knowledge and

workflow management (Mulligan, 2002). On the

other hand, researchers position knowledge as a

“baseline for the serviceability and the

maintainability” of the components and systems

involved in providing IT services in continuity that is

in line with the current and planned business

requirements (Blanchard, 1995). Teece et al. (1997)

define “dynamic capabilities” as “the firm’s ability to

integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and

external competencies to address rapidly changing

environments” (p. 516). The argument is made that

dynamic capabilities are shaped by the coevolution of

these learning mechanisms was expressly made

(Zollo and Winter, 2002).

2.2 Knowledge Transfer as Essential

Organizational Capability

Dynamic capabilities are enabled by knowledge

infrastructures (Easterby-Smith and Prieto, 2008). In

organizational learning contexts, the organization’s

capability to take on the associated learning curve

was related to the organization’s absorptive capacity

(Cohen and Levinthal, 1990). Certain organizations

are able to acquire and assimilate new external

knowledge, but are not able to transform and exploit

it successfully in order to create value from their

absorptive capacity (Kranz et al, 2016). These

capabilities rely fundamentally on the organization’s

absorptive capacity and build on prior development

of its constituent, individual, absorptive capacities

(Lane et al, 2006). Mechanisms associated with the

coordination capabilities (i.e. cross-functional

interfaces, participation, and job rotation) primarily

enhance potential absorptive capacity increasing the

acquisition, assimilation and transformation of new

external knowledge. This component of absorptive

capacity provides organizational units with strategic

advantages (Lai et al, 2016), such as greater

flexibility in reconfiguring resources (Tsai, 2001),

and effective timing of knowledge deployment

(Szulanski and Jensen, 2016). Certainly, a moderating

effect of knowledge complexity on the relationship

between organizational learning capability and

technological innovation implementation was

indicated (Mat and Razak, 2011), and related to

organizational attributes (Forés et Camisón, 2016).

External knowledge transfer was identified as a key

factor in integrating technology (Frank and Ribeiro,

2014) and an antecedent to innovation integration

(Teo and Bhattacherjee, 2014). Outsourcing

activities, often including a strategic partner were

identified to facilitate the knowledge transfer into the

organization (Naghavi and Ottaviano, 2010). Further,

research has posited that organizations acquire

information and transform it into collective

knowledge assets (Legris and Collerette, 2006) often

through the use of knowledge management systems

(KMS) (Alavi and Leidner, 2001) with a strong

dependency on IT leadership communication and

governance practices.

Leadership capabilities in fostering business to IT

communication and governance as well as the

readiness of IT and the level of stakeholder

participation are critical success factors (Rau, 2004).

Handoff and communication best practices between

advance technology groups and operations groups

help drive knowledge diffusion into the

organizational structure (Esteva, et al, 2006).

Nonaka’s broad contribution to the theory of

organizational knowledge creation (Nonaka, 1994)

emphasizes that organizational knowledge is created

through a continuous dialogue and transformation

between tacit and explicit knowledge (Nonaka, et al,

1996). However, such models can be highly

theoretical with empirical shortcomings of

information divergence into inadequate knowledge

creation that may overlook concepts of culture,

context and objectives for this transformation

(Gourlay, 2003). Thus, as it relates to the innovation

capability of IT organizations, a gap can be identified.

Nevertheless, the extant literature lacks

mechanisms by which IT organizations maintain the

level of knowledge and knowledge transfer

capabilities required to confidently integrate

emerging IT in a dynamic environment of rapid

technological change. Theory has not yet addressed

potential obstacles to business model innovation

based on emerging IT integration that may constrain

knowledge acquisition and transfer capabilities of the

IT organization that is involved in integrating

emerging technologies and hinder IT from building

on organizational knowledge.

This paper explores how IT organizations in IT

services companies apply knowledge acquisition

practices to transition themselves to a lever rather

than a barrier to integrating innovation.

3 METHODOLOGY

This exploratory research into practice levers two in-

depth qualitative case studies (Yin, 2009). Case study

methodology has been used to study knowledge

transfer practices in similar contexts (Chugh, 2015;

Rottman, 2008; Lee and Lee, 2000). Research

activities followed a case study protocol (Appendix -

Table 1) conducted in three stages, on location with

IT organizations in a telecom services Company A,

and in an application hosting services Company B,

selected purposefully (Patton, 1990) for this study.

3.1 Site Selection

Company A is a leading internet services provider

and hosting solutions, established in 1995 with 130+

employees. The IT organization is composed of 15

members managing security credentials, moves and

changes of the internal users; planning of new

technology deployment; internal and external

customers. Over a 2.5 year project launched in the

beginning of 2010, Company A implemented a new

business process management application based on

emerging BPM (Business Process Management)

technology to support the operational activities of the

company in delivering these new services and

reporting on the related activities. Leveraging BPM,

Company A adapted the way of doing business and

changed the operational systems, organizational

structures and pricing models, to support the

integration of the new mobile services in the market.

The disruption to the IT organization and the business

organization was substantial. The IT management

team faced a user base resisting change and

reluctance from the IT staff to adopt and adapt the

new application.

Company B’s business, on the other hand, is in

hosting and cloud services, re-established in 2006

with 42 employees in total. 12 employees form the IT

organization in charge of the planning,

implementation and support of the internal

infrastructure with a service desk attending to

escalated customer calls. With a challenge to serve

the internal IT needs and the needs of external

customers, such as onsite support, the IT organization

of Company B was reluctant to use the emerging

cloud technologies even for their internal systems. IT

leadership had to manoeuvre their IT organization to

support a public cloud service. From reallocating

budgets to hiring qualified consultants to supplement

the resources and transition the knowledge, the IT

organization of Company B, in face of this

disruption, had to leverage the company resources

properly and extensive employee training and

knowledge building programs were implemented.

Additionally, in order to support this new service,

Company B needed a service desk and a portal to be

integrated into their application hosting services

support platform in order to provide the customer

required service levels. This presented yet another

disruption and exposed the already burdened IT

organization supporting the customer facing services

to undertake an internal project.

Similarities in the sites selected reinforce the

findings by adding depth into the discovery;

similarities to note are of industry context (Miles et

al., 2000), culture (Kwon, 1990), international

presence (Zmud, 1982), IT organization setting:

centralized management model (Damanpour, 1991)

with a collective decision making (Rogers, 1962).

These sites also present complementarities where by

Company A implemented an internally facing

solution to enable an external service and Company

B deployed a solution that is used by both internal and

external customers. The choice of these sites aimed to

uncover potential cross case observations further

enriching the empirical study. The sites differ in

organization size (Fichman and Kemerer, 1997),

maturity (Kwon 1990; Grover and Goslar, 1993) and

the scope of their project implementation.

3.2 Data Collection and Analysis

Data Collection instruments were developed to

capture input from the activities (Appendix – Table

2). A preparation meeting set the stage for the

activities and helped identify key informants that

could represent a cross section of institutional

knowledge. Discovery workshops followed with data

collection activities that combined interviews and

brainstorming sessions (Hargadon and Sutton, 1997).

Focus group workshops were conducted due to the

nature of the topic that requires stimulation and

interaction (Stewart et al, 2007). These workshops

recorded all the participants’ input while probing for

details; where possible, using illustrative examples to

help establish neutrality in the process (Patton, 1990).

In total data collection involved 15 informants chosen

from the two companies. Saturation interviews were

subsequently conducted with senior managers from

each company. Case summaries and cross-case

comparison were compiled in a tabular summary

(Creswell, 1998), in the form of interview transcripts,

field notes from observations, and relevant exhibits

(e.g. organizational structures, web sites of each

company, company presentations material). The data

analysis investigated the data correlation through a

predefined coding system (Miles and Huberman,

1991) in order to organize the data and provide a

means to introduce the interpretations (Strauss and

Corbin, 1990). A step by step ‘Key Point’ coding

technique (Allan, 2003) was applied to the interview

transcripts (Douglas, 2003), and relevant concepts are

identified. Finally, an open discussion forum was

conducted among all participant at each company

separately in order to deepen the concepts.

This paper is part of a developed study. It focuses

on one Key Concept of Knowledge Acquisition that is

isolated by the coding technique to support the

findings and focus on one significant observation

(Appendix – Table 3). Codes to the seed concept were

grounded in the literature with references to notions

of seeking external knowledge (Pugh and Prusak,

2013), transferring of acquired knowledge (Alavi and

Leidner, 2001; Gatewood, 2009), and internal

diffusion of acquired knowledge (Roberts et al,

2012); then exploiting this knowledge in participation

in decision making (Jansen et al, 2005; Xue et al,

2008) and training (Edwards and Peppard, 1997).

Concepts are allowed to emerge from the coding

technique. The coding results were then shared in a

discussion with the participants is focus group

sessions for validation and additional input.

4 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

The case study has revealed that through training of

IT in both technology and in the related business

aspects, IT organizations in the IT services industry

were able to shape their technical and analytical

capability (i.e. analysis of the business requirements,

ROI, business value of technology) and become

enablers of innovation. IT organizations previewed

the business and technical benefits of potential

solutions. This was an opportunity to embed

visionary and forward looking IT solutions into the

firm. The IT Director of Company A explicated that

“This tactic has fuelled the enthusiasm of the IT

organization and raised the confidence of the

business in the IT organization and elevated the value

of the IT organization to the business.” The IT

organization became part of the strategic trend setting

capacity of the organization, which encouraged the

members of the IT organization to embrace the new

deployment. The opportunity to lead internally

reportedly raised the “confidence” of the business in

IT organizational capabilities and encourages the IT

organization to embrace the new technology. IT

became an agent of change, elevating the value of IT

in the organization and innovating the business. The

IT organization was then empowered to drive the next

phases of the implementation of the IT based business

innovation. For instance, the IT team of Company A

was involved in all new systems introductions and the

IT organization, in the case of the BPM

implementation, was able to introduce process

automation initiatives and be a leader in the

company’s business model innovation. IT leadership

managed to “push other concepts that were originally

outside the scope of the current project such as

shopping carts, self-service and collection activities,

integration of handhelds, enabling the POS platforms

and other mobile applications, added the Director of

IT, explaining how such approaches expanded the

innovative aspect of the solution and helped drive a

niche service offering to the market.

4.1 Knowledge Acquisition Practices

Indeed, knowledge acquisition practices were

identified as key enablers to IT organizational

capabilities. Both companies suggested that IT

organizations could be better prepared for the

integration of EIT primarily through Knowledge

Acquisition mechanisms of training, seeking external

knowledge and sharing it internally.

For Company A, the IT organization’s learning

capabilities were enhanced by attending conferences:

an opportunity to network with peers and learn then

disseminate the knowledge internally. “First we send

them to conference. They will then have a chance to

network with peers and learn, gain the confidence

with the technology and come and convey the

knowledge internally” indicated the operations

manager of Company A. The degree of tacit-ness of

newly acquired knowledge necessitated richer

organizational information processing mechanisms.

An integration working group made up of cross

organizational members and representations of IT in

the business led the knowledge transfer in Company

A. Job rotations enhanced knowledge redistribution

among the technical IT team members. In order to

address the architectural implications and learn about

potential system interaction with existing systems

(e.g. Active Directory support), Company A started

architectural review session emphasizing the role of

external consultants in order to insource the required

knowledge.

On the other hand, organizational dynamics of

socialization (the perspective of a group rather than

an individual) practiced by the IT organization

stimulated Company B’s sales team to increase the

organization’s business-IT knowledge. The

participation of IT in the process of decision making

primarily strengthened the realized absorptive

capacity (Jansen et al, 2005) of the IT organization

and elevated the organization’s capability to

strengthen their business-IT knowledge. Company B

conducted research of other implementations in peer

organizations in a form of knowledge networks with

the objective of insourcing the required knowledge.

Thus, external knowledge was sought through the

engagement of consultants and joint R&D activities

with key providers and partners. Testing and R&D

activities enriched the individual skills of the IT

employees. Their accumulated experience increased

the levels of organizational knowledge. “… We setup

R&D efforts with peer organizations, key partners

and suppliers and review and research other

implementations in peer organizations” (Company

B). Learning capability of experimentation (Cohen

and Levinthal, 1990), and interaction with external

environments (Varis and Littunen, 2010) were shown

by research studies to positively associate with the

introduction of novel product innovations in firms.

4.2 Knowledge Transfer Tactics

The transfer of knowledge to internal customers (i.e.

employees of the company) was accomplished

through user training sessions and users’ manuals.

The task for the IT organization was then also to

participate in “educating the customer to increase the

enthusiasm at the customer level”. This helped

Company A overcome users’ resistance to adopting

the new business process management (BPM)

platform and eased the task on the IT organization.

Case management and monitoring tools provided

feedback from the customer into the business

planning to drive alignment of the objectives of the

business. Such tools enabled the IT organization of

Company A to gain visibility into the customer

experience and to measure the service health

(metrics) through related monitoring and reporting

functions. This awareness incentivized the IT

organization to handle the implementation of EIT

with the knowledge of the impacts it had on the

customer.

Collaboration and brainstorming sessions helped

disseminate the acquired knowledge and knowledge

management systems consolidated this knowledge in

to an information base on internal and external

customers. Company B used this convergence of

information to participate in delivering the vision

internally with an enthusiasm to contribute input. The

operations executive of Company B described that

“knowledge transfer tactics between the teams were

applied. They involve the sorting and categorization

of information with knowledge management systems

in order to leave time for the internal functionality

empowering the front lines. Through communication

between these teams, the internal team is aware of the

customer issues. This was fruitful in the ability of IT

to participate in delivering the vision internally with

an excitement, progress and ability to participate

effectively in the input”.

Extending outside the boundaries of the firm, for

Company B, continual training plans empowered the

IT organization to become more effective in

supporting the customer base. Training sessions were

carried in-house. Chosen team members were

assigned and trained on specific technologies. They

attended conferences to stay ahead of the learning

curve and setup labs and databases of training

materials for in-house training activities. In-house

training facilitated the spread of knowledge and

reduced the corresponding knowledge acquisition

costs. Company B involved the employees, as their

internal customers, in the deployment of hosting

projects. The IT organization established biweekly

knowledge sharing sessions with internal customers

(employees) in order to discover the challenges and

help reduce adoption issues.

In addition to the benefits received from

collaboration tools, Company B included knowledge

management systems in their toolset as part of their

knowledge sharing strategy. These knowledge

management and transfer capabilities built on the

organizational knowledge to improve the

operational/functional competences of Company B

by combining the knowledge of the customer facing

technical teams and the internally facing IT

infrastructure teams (Company B).

4.3 Exploiting the Tacit Knowledge of

the Customer

Emerging from the analysis is a concept that depicts

the phenomenon of exploring the tacit knowledge of

the customer. This study shows a potential added

value for IT organizations that collaborate with the

customer of their services, especially in mitigating

risks and improving eventual outcomes (Liu et al,

2013). Company B reported that the IT reluctance

phenomena extending to their customers hindered

their ability to provide their services to these

customers. Learning workshops held with the

customers, increased the awareness of the customer

issues and reduced the customer reluctance to adopt

the technology. To close the loop, IT shared lessons

learned from solving customer issues with the

business as they brought forth recommendation to

drive more business through new products and

services. This stimulated the creativity of the IT team,

as a motivation to start driving the innovative ideas

through to the business strategy. Company B

reportedly focused on enhancing the consultancy

skills of the engineers. The “IT organization was a

consultant to the customer … the IT team scouted for

opportunities at the customers’ base, and feedback is

brought back to the business” clarified the operations

manager. Their exposure as a consultant with the

external customer motivated their creativity as they

started driving the innovative ideas through to the

business strategy. On the operations side, and in close

communication with the customer-facing support

teams, the IT organization was aware of the customer

issues. The IT support team (customer facing) in

Company B meets with the IT infrastructure team

(Internal team) regularly to review the customer

issues, build the knowledge base and solicit the

collaboration of ideas across the technical team

internal and external. Meanwhile, the customer facing

support teams, share the lessons learned from solving

customer issues with the business. This works as a

feedback into the business of the issues facing IT

which may in turn drive a business solution or a new

service.

5 CONCLUSION AND

GUIDANCE FOR PRACTICE

Building upon the theory of organizational

knowledge creation, these findings are reminders of

Nonaka’s model of spiral of organizational

knowledge creation (Nonaka, 1994) through

combining tacit and explicit knowledge into a cyclic

process of organizational knowledge building.

Thus, our study could be considered as an

empirical extension of this theory. Mechanisms for

knowledge acquisition and knowledge transfer

explored maybe framed reciprocally, by the two

dimension of organizational knowledge creation lens:

(1) mechanisms for the acquisition of knowledge that

relate to the type of knowledge (tacit vs. explicit) and

(2) knowledge transfer tactics that depend on level of

social interaction to convert this knowledge into

organizational asset.

5.1 Mechanisms for Knowledge

Acquisition and Transfer

The site selection proved helpful in highlighting the

different mechanisms of knowledge acquisition and

transfer, however analogous, they seem nuanced

relative to project scope.

In the case of Company A, a heightened focus

was clear on building the organizational learning

capabilities that addresses the internal customer needs

as the project’s scope was mostly internal in scope.

Job rotations were instrumental in building a deep

knowledge bench. IT team members attended

conferences and networked with peers to seek

external knowledge, formed cross organizational

integration groups. Resorting to external resource

augmentation in order to insource required new

knowledge, conducting training sessions to transition

knowledge to users and reduce adoption resistance.

Tools deployed were case management and

monitoring that gathered information and converted it

into organizational knowledge.

Company B’s project on the other hand, was

more pervasive in scope. The customer base was

preliminarily external to the firm. The IT organization

had to reach outside the firm’s boundary to seek new

knowledge through the engagement of consultants

and joint R&D activities with key providers and

partners, researching other implementations in peer

organizations in a form of knowledge networks with

the objective of insourcing the required knowledge.

Collaboration and brainstorming sessions among

members of the IT organization the acquired

knowledge and knowledge management systems

consolidated this knowledge in to an information base

on internal and external customers. Continual training

plans empowered the IT organization to become more

effective in supporting the customer base and learning

workshops held with the customers, increased the

awareness of the customer issues and reduced the

customer reluctance to adopt the technology. They

also included knowledge management systems in

their toolset as part of their knowledge sharing

strategy.

5.2 Enabling IT Organization’s

Capability for Innovation

In either case, the empirical statements explicate that

IT organization embrace innovation integration by

reinforcing knowledge acquisition practices through

training, collaborations with key partners and

suppliers, testing and R&D. IT organizations

reportedly gained confidence with emerging

technology integration by capitalizing upon learning

opportunities from peer networks, consultants and

conducting joint R&D activities with key providers

and partners. Acquired knowledge is then shared

internally in cooperation with the business and other

team members through the integration of new ideas

with the use of knowledge management tools,

research and testing practices. Tools for knowledge

management consolidated this knowledge into an

information base on external and external customers.

In both cases, the customer was an integral part of

the knowledge institutionalization process. In one

case (Company A), internal testing and R&D

activities enriched the individual skills of the

employees. The participation of IT in the process of

decision making elevated the organization’s

capability to strengthen their business-IT knowledge

and job rotations enhanced knowledge redistribution

among the technical IT team members. Acquired

knowledge is mutualized in a collaborative approach

with customers. The IT organization learns about the

customer issues (supporting them more effectively)

and about their needs and requirements, which

reinforced the ability of IT to support the vision of the

business. A suggestion that customer collaboration

would likely ease of adoption of the new service

(especially for the internal customer of the IT

organization), and prepare the IT organization for the

potential risk induced by the emerging technologies

to the external customer. Integration working groups

connect with the business to gain insight into the

business requirements from IT and gauge the business

readiness for the IT innovation. Then cooperating

with customers (i.e. internal customer of IT and

external customer of the business and IT) in testing,

planning, and risk assessment, IT organizations could

influence the customer’s readiness for integrating

innovation. Furthermore, collaboration and

brainstorming sessions helped disseminate the

acquired knowledge. Integration working groups

made up of cross organizational members and

representations of IT in the business lead the

knowledge transfer. Integration working groups

connect with the business to gain insight into the

business requirements from IT and gauge the business

readiness for the IT innovation.

5.3 Emphasizing the Confluence of

Knowledge

This study shows that IT organizations must

continually build, adapt, and reconfigure their

competences to succeed in a changing environment

through knowledge acquisition and transfer

mechanisms. These mechanisms underscore the

development of dynamic organizational capabilities

of exploration and exploitation, emphasizing the

confluence of knowledge. Investments are required to

build IT skills and competence, muster key resources,

and formalize key activities. Innovative IT

organizations develop key partnership with suppliers

and peers, and exploit the tacit knowledge of the

customer. IT leadership of confident organizations

drive their organizational capabilities to become

levers for business model innovation. They motivate

their IT organizational learning capabilities, and

reinforce their analytical capabilities. They

demonstrate leadership competence, encourage the

adoption of standards and networking with peers.

Learnings from this study highlight the fact that

the confluence of knowledge from the customer base,

the business, peer organizations, standards and best

practices, has the potential of increasing the

exploratory and exploitative capabilities, raising the

awareness, analytical skills and the confidence of IT

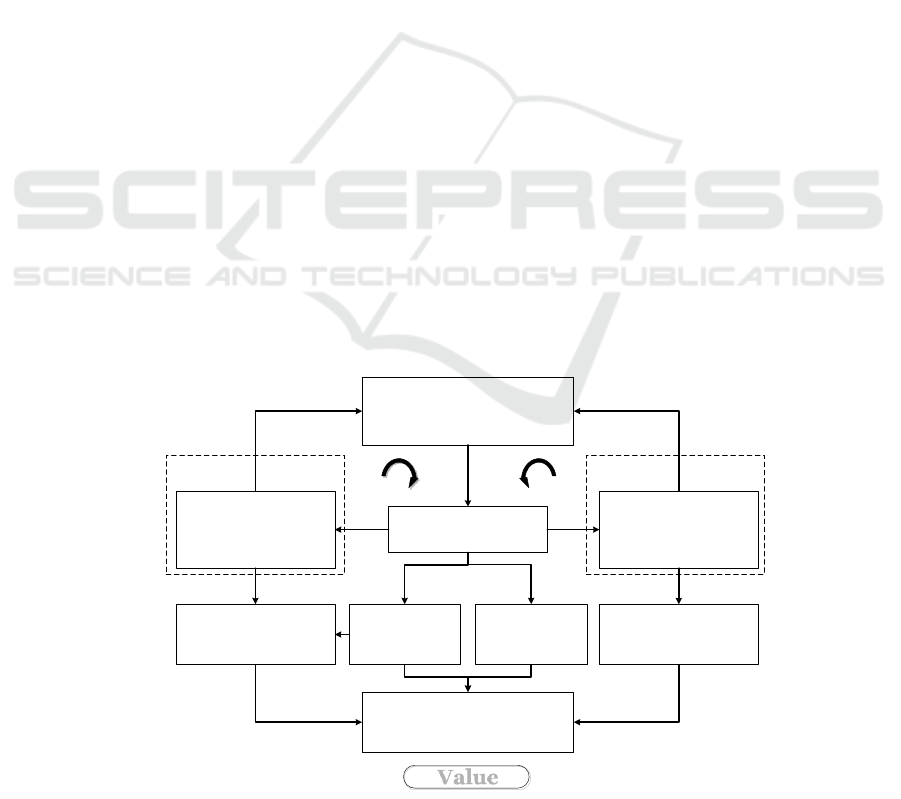

organizations to “integrate new ideas and embrace

emerging technologies”. Knowledge flow between

the exploratory and the exploitative IT teams (Jansen

et al, 2009) converges into a potential for innovation

(Appendix – Fig. 1). This confluence of knowledge

becomes a cyclic process of exploration and

exploitation of knowledge assets in a perpetual

knowledge sharing ecosystem that yields to a

continuous organizational learning with significant

value to organization capability building.

5.4 Limitations and Opportunities for

Further Research

This paper is part of a larger research effort exploring

mechanisms of innovation integration employed by

IT organizations (Badr, 2014; 2015; 2016). The

specific topic of this paper treats those mechanisms

of knowledge management adopted to prepare IT

organizations for innovation integration. Findings of

this study corroborate evidence that tacit knowledge

transfer is often supported by open communication,

peer-trust and unrestricted sharing of knowledge

(Chugh, 2015). Although the research has reached its

aim, some unavoidable limitations can be noted. The

study was conducted in two companies, hence limits

the generalisability of the findings. Limitations

related to case study research the research and other

contexts such as culture and industry can be

recognized (Al-Ammary, 2014).

The indicated limitations of this study could offer

opportunities for follow on research. For instance,

additional field work possibly in the form of wider

focus groups, with chief information officers, IS

professionals and consultants (Rosemann and

Vessey, 2005) would examine the applicability of the

framework in other cultural, organizational and other

contexts, in order to strengthen the practice

implications of the concepts introduced by this study

(Rosemann and Vessey, 2008). Academic researchers

in IT innovation, MIS, organizational dynamic

capabilities and resource based views would find the

opportunity to exploit the findings of this study into

interesting quantitative and qualitative projects.

REFERENCES

Al-Ammary, J. (2014). The strategic alignment between

knowledge management and information systems

strategy: The impact of contextual and cultural factors.

Journal of Information and Knowledge Management,

13(01), 1450006.

Alavi, M., Leidner, D. (2001). Review: Knowledge

Management Systems: Conceptual Foundation and

Research Issues. MIS Quarterly Vol. 25-1, pp. 107-136.

Allan, G. (2003). A Critique of Using Grounded Theory as

a Research Method. Electronic Journal of Business

Research Methods, 2(1), 1-10.

Badr, N. (2014). Integration of IT Based Business Model

Innovation: Potential Challenges in Integrating

Emerging Technologies. Business Leadership Review

DBA Special Issue: Impact & Practice: Making the

DBA Count. Issue 12: Vol. 1 (DBA) June 1, 2014.

Badr, N. G. (2015). Empowering IT organizations’

Capabilities of Emerging Technology Integration

through User Participation in Innovations Based on IT.

A Multi-Disciplinary View on Enterprise, Public Sector

and User Innovation, Digitally Supported Innovation,

Vol. 18, Lecture Notes Information Systems,

Organization. ISBN 978-3-319-40264-2.

Badr, N. G. (2016). Integrating Emerging Technologies in

IT Services Companies: The “Driver” CIO. 22nd

Americas Conference on Information Systems, San

Diego, 2016. Manuscript ID AMCIS-0127-2016. R2.

Barney, J. B. (1991) Firm Resources and Sustained

Competitive Advantage, Journal of Management (17) 1,

pp. 99-120.

Benamati, J., Lederer, A. L. (2010). Managing the Impact

of Rapid IT Change. Information Resources

Management Journal, 23(1), 1-16.

Berthon, P., Hulbert, J. M., Pitt, L. F. (1999). To serve or

create? Strategic orientations toward customers and

innovation. California Management Review, 42(1), 37-

58.

Blanchard, S. B., (1995). Maintainability: A Key to

Effective Serviceability and Maintenance Management,

John Wiley and Sons Inc., New York 1995.

Byrd, T. A., Turner, E.D. (2000). An Exploratory Analysis

of the Information Technology Infrastructure

Flexibility Construct. Journal of MIS, 17(1), 167-208.

Chugh R. (2015). Do Australian Universities Encourage

Tacit Knowledge Transfer? In Proceedings of the 7th

International Joint Conference on Knowledge

Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge

Management - Volume 1: KMIS, (IC3K 2015) ISBN

978-989-758-158-8, pages 128-135.

Cohen, W. M., Levinthal, D. (1990). Absorptive Capacity:

A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 35: 128–152.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative Inquiry and Research

Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

Damanpour, F. (1991). Organizational Innovation: A Meta-

Analysis of Effects of Determinants and Moderators,

AOM Journal (34:3), 1991, pp. 555-590.

Dan, Y., Chang Chieh, H. (2010). A Reflective Review of

Disruptive Innovation Theory. International Journal of

Management Reviews, 12(4), 435-452.

Douglas D. (2003), Inductive Theory Generation: A

grounded Approach to Business Inquiry, Electronic

Journal of Business Research Methods, Vol. 2-1, Art.

4, Academic Conferences International Limited, 2003.

Easterby-Smith, M., Prieto, I. M. (2008). Dynamic

Capabilities and Knowledge Management: an

Integrative Role for Learning? British Journal of

Management, 19(3), 235-249.

Edwards, C., Peppard, J. (1997). Operationalizing Strategy

through Process. Long Range Planning, 30.

Esteva, J., Smith-Sharp, W., and Gangeddula, S. (2006). A

Formal Technology Introduction Process. Journal of

American Academy of Business, Cambridge, 9(1), 40-

46.).

Fichman, R. G., Kemerer, C. F. (1997). The Assimilation of

Software Process Innovations: An Organizational

Learning Perspective, Management Science (43:10),

1997, pp. 1345-1363.

Forés, B., Camisón, C. (2016). Does incremental and

radical innovation performance depend on different

types of knowledge accumulation capabilities and

organizational size? Journal of Business Research,

69(2), 831-848.

Frank, A. G., Ribeiro, J. L. D. (2014). An integrative model

for knowledge transfer between new product

development project teams. Knowledge Management

Research & Practice, 12(2), 215-225.

Galliers, R. D., Leidner, D. E. (2014). Strategic information

management: challenges and strategies in managing

information systems. Routledge.

Gatewood, B. (2009). Clouds on the Information Horizon:

How to Avoid the Storm. Information Management

Journal, 43(4), 32-36.

Gourlay, S. (2003). "The SECI model of knowledge

creation: some empirical shortcomings." pp 377-385.

Grant, R.M. (1991). The resource-based theory of

competitive advantage: Implications for strategy

formulation. California Management Review, 33(3),

114-135.

Grover, V., Goslar, M. D. (1993). The Initiation, Adoption,

and Implementation of Telecommunications

Technologies in U.S. Organizations. Journal of MIS,

10(1), 141-163.

Hargadon, A. B., Sutton, R. I. 1997. Technology Brokering

and Innovation in a Product Development Firm.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 42: 716–749.

Jansen, J. J. P, Tempelaar, M.P., van den Bosch, F. A. J.

Volberda H. W. (2009). Structural Differentiation and

Ambidexterity: The Mediating Role of Integration

Mechanisms, Organization Science. Vol. 20, No. 4,

July–August 2009, pp. 797–811.

Jansen, J.J., Van den Bosch, F.A.J., Volberda, H.W. (2005).

Managing Potential and Realized Absorptive Capacity:

How Do Organizational Antecedents Matter? AOM

Journal, 48, 6, 999–1015.

Keel, A. J., Orr, M. A., Hernandez, R. R., Patrocinio, E. A.,

Bouchard, J. (2007). From a technology-oriented to a

service-oriented approach to IT management. IBM

Systems Journal, 46(3), 549-564.

Kranz, J. J., Hanelt, A., Kolbe, L. M. (2016).

Understanding the influence of absorptive capacity and

ambidexterity on the process of business model

change–the case of on

‐

premise and cloud

‐

computing

software. Information Systems Journal.

Kwon, T. H. A (1990) Diffusion of Innovation Approach to

MIS Infusion: Conceptualization, Methodology, and

Management Strategies. Proceedings of the 10

th

International Conference on Information Systems.

Copenhagen, Denmark, 1990, 139-146.

Lai, J., Lui, S. S., Tsang, E. W. (2016). Intrafirm

Knowledge Transfer and Employee Innovative

Behavior: The Role of Total and Balanced Knowledge

Flows. Journal of Product Innovation Management,

33(1), 90-103.

Lane, P. J., Koka, B. R., & Pathak, S. (2006). The

reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and

rejuvenation of the construct. Academy of management

review, 31(4), 833-863.

Lee, Z., and Lee, J. (2000). An ERP implementation case

study from a knowledge transfer perspective. Journal of

information technology, 15(4), 281-288.

Legris, P., Collerette, P. (2006). A Roadmap for IT Project

Implementation: Integrating Stakeholders and Change

Management Issues. Project Management Journal,

37(5), 64-75.

Liu, J. Y., Yang, M., Klein, G., Chen, H. (2013). Reducing

User-related Risks with User-developer partnering.

Journal of Computer Information Systems, 54(1), 66-74.

Mat, A., and Razak, R. (2011). The Influence of

Organizational Learning Capability on Success of

Technological Innovation (Product) Implementation

with Moderating Effect of Knowledge Complexity.

International Journal of Business and Social Science,

2(17), 217-225.

Miles, M. and Huberman, A.M. (1991). Qualitative Data

Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Sage

Publications, Newbury Park, CA, USA.

Miles, R. E, Snow, C. C., Miles, G. (2000). TheFuture.org,

Long Range Planning, 33/3 (June 2000): 300-321).

Mocker, M. and Teubner, A. (2005). Towards a

Comprehensive Model of Information Strategy (2005).

ECIS 2005 Proceedings. Paper 62.

Mulligan, P (2002). Specification of a Capability-based IT

Classification Framework. Information and

Management 39, 8, pp. 647 - 658.

Naghavi, A. and Ottaviano, I. P. G., (2010). Outsourcing,

Complementary Innovations, and Growth. Industrial

and Corporate Change, Volume 19, Number 4, pp.

1009-1035 Advance Access published Jan. 21, 2010.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational

knowledge creation. Organization science, 5(1), 14-37.

Nonaka, I., Von Krogh, G., and Voelpel, S. (2006).

Organizational knowledge creation theory:

Evolutionary paths and future advances. Organization

studies, 27(8), 1179-1208.

Nonaka, L., Takeuchi, H., and Umemoto, K. (1996). A

theory of organizational knowledge creation.

International Journal of Technology Management,

11(7-8), 833-845.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research

methods (2nd Ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Pugh, K., Prusak, L. (2013). Designing effective knowledge

networks. MIT Sloan Man. Rev., 55(1), 79-88.

Roberts, N., Galluch, P. S., Dinger, M., Grover, V. (2012).

Absorptive Capacity and Information Systems

Research: Review Synthesis, and Direction for Future

Research. MIS Quarterly, 36(2), 625-A6.

Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of Innovations. New York:

Free Press.

Rosemann, M., Vessey, I. (2005). Linking Theory and

Practice: Performing a Reality Check on a Model of IS

Success, in Proceedings of the 13th European

Conference on Information Systems, D. Bartmann, F.

Rajola, J. Kallinikos, D. Avison, R. Winter, P. Ein-Dor,

J. Becker, F. Bodendorf, C. Weinhardt (eds.),

Regensburg, Germany, May 26-28.

Rosemann, M., Vessey, I. (2008). Toward Improving the

Relevance of Information Systems Research to

Practice: The Role of Applicability Checks. MIS

Quarterly, 32(1), 1-22.

Rottman, J. W. (2008). Successful knowledge transfer

within offshore supplier networks: a case study

exploring social capital in strategic alliances. Journal

of Information Technology, 23(1), 31-43.

Stewart, D. W., Shamdasani, P. N., and Rook, D. W.

(2007). Focus Groups: Theory and Practice. Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative

Research. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.

Szulanski, G., Ringov, D., and Jensen, R. J. (2016).

Overcoming Stickiness: How the Timing of Knowledge

Transfer Methods Affects Transfer Difficulty.

Organization Science, 27(2), 304-322.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., and Shuen, A., (1997). Dynamic

Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic

Management Journal 18 (7): 509–533.

Teo, T. S. H. and W. R. King (1997). “Integration between

Business Planning and Information Systems Planning:

An Evolutionary-Contingency Perspective.” Journal of

MIS 14(1): 185-214.

Teo, T. S., and Bhattacherjee, A. (2014). Knowledge

transfer and utilization in IT outsourcing partnerships:

A preliminary model of antecedents and outcomes.

Information & Management, 51(2), 177-186.

Tsai, W. (2001). Knowledge Transfer in Intra-

organizational Networks: Effects of Network Position

and Absorptive Capacity on Business-unit Innovation

and Performance. AOM Journal, 44: 996– 1004.

Tushman, M., Anderson, P. (1986). Technological

Discontinuities and Organizational Environments.

Administrative Science Quarterly 31(3):439-465.

Varis, M., Littunen, H. (2010). Types of Innovation,

Sources of Information and Performance in

Entrepreneurial SMEs. European Journal of Innovation

Management, 13 (2), 128-154.

Xue, Y., Huigang, L. Bolton, W.R. (2008). Information

Technology Governance in Information Technology

Investment Decision Processes: The impact of

investment characteristics, external environment, and

internal context, MIS Quarterly 32(1): 67–96.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and

Methods. 4th Edition. Newbury Park, CA: Sage ISBN:

978-1-4129-6099-1.

Zmud, R.W. (1982). Diffusion of Modern Software

Practices: Influence of Centralization and

Formalization. Management Science (28:12), 1982, pp.

1421-1431.

Zollo, M., S. G. Winter (2002). Deliberate learning and the

evolution of dynamic capabilities, Organization

Science, 13 (3), pp. 339–351.

APPENDIX

Figure 1: A Confluence of knowledge for continual organizational learning.

IT – Business

Alignment

IT – Customer

Collaboration

IT team is aware of the

customer issues (support)

and requirements

(consulting).

Integration of new ideas &

technology with proper

research & testing practices

(Collaboration and Decision

Making)

IT managers with an

initiative to embrace new

technology (Incentives,

Working environment, )

Ability of IT to participate in

delivering the vision

internally

Acquire Knowledge

Training, Networking with peers, R&D,

external resources, providers &

partners, SMEs, etc.

Share Knowledge

Value

IT Organization

Embraces Emerging

Technology

Increase Confidence

of IT in IT & of

Business Units in IT

Increase Analytical

Skills of IT

Continuous

Continuous

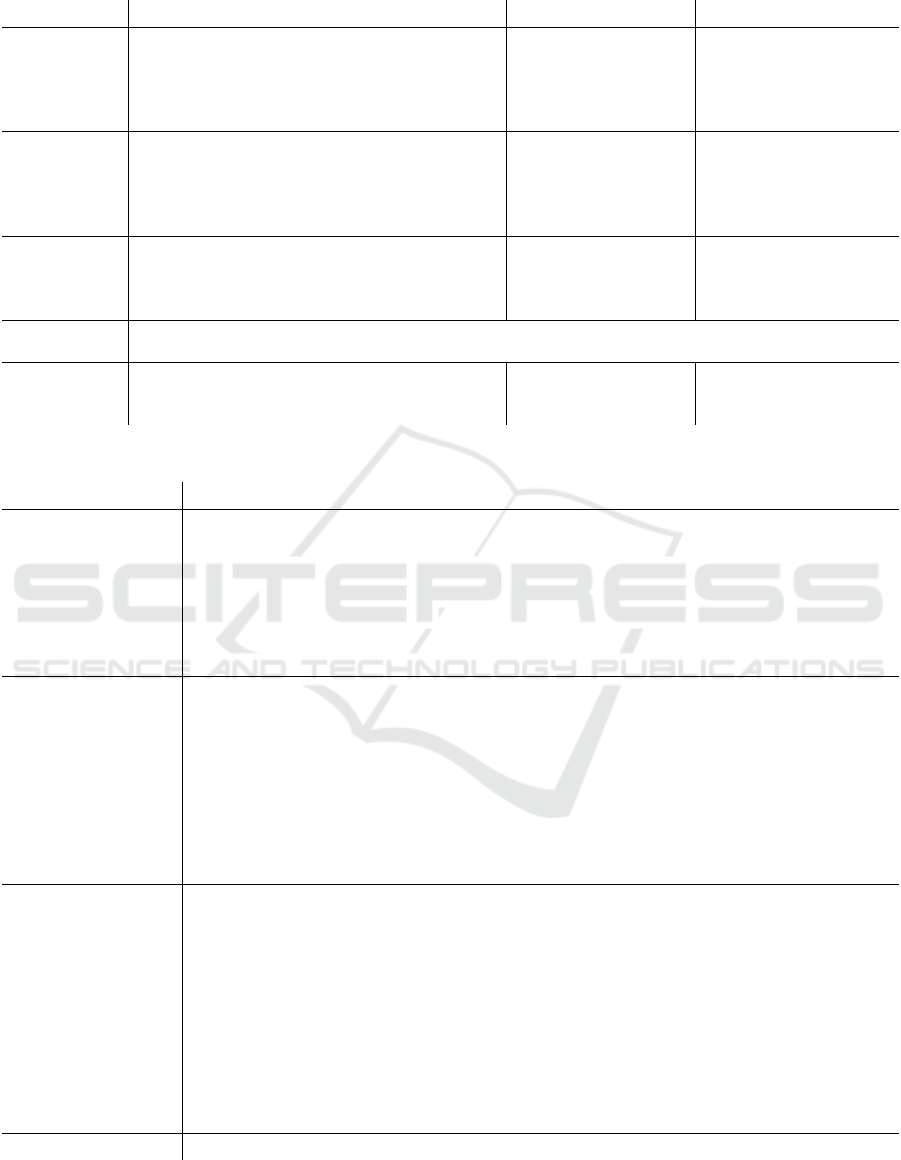

Table 1: Case Study Protocol.

Stage

Activity

Participants (A)

Participants (B)

Preparation

Meeting

Semi-structured (1:1) interview with the primary

contact; Identify and collect secondary data

documents and artefacts; Review company and

IT organizational structure; Identify stakeholders

for the data collection stages

Director of IT

Deputy GM / Operations

Director

Stage 1

“Discovery”

workshop

Conduct the first “discovery” workshop (middle

management); Gather collective knowledge on

the mechanisms that reduce reluctance of the IT

organization to integrate emerging technology

innovations in IT

Director of IT; IT

Admin.; IT Project

Mgr.; MIS Systems

Analyst; IT Systems

Mgr.; MIS / IT Mgr.

Deputy GM / Operations

Dir.; Infrastructure Mgr.

Customer Support Mgr.

Customer Support Sup.

Sr. Sys. Engineer

Stage 2 -

Saturation

Conduct semi-structured interviews ( senior level

management); Collect additional detail on the

role of leadership and seek saturation of the

concepts

General Manager; VP

of Sales

General Manager / Sales

Manager

Develop Case

Reports

Create individual summary of each transcript (reduction process) and combine case response and

individual transcript summaries.

Stage 3 -

Discussion

Conduct the second “Discussion” workshop;

Unstructured discussion and feedback workshop

for member checking and validation

Same as stage 1

Same as stage 1

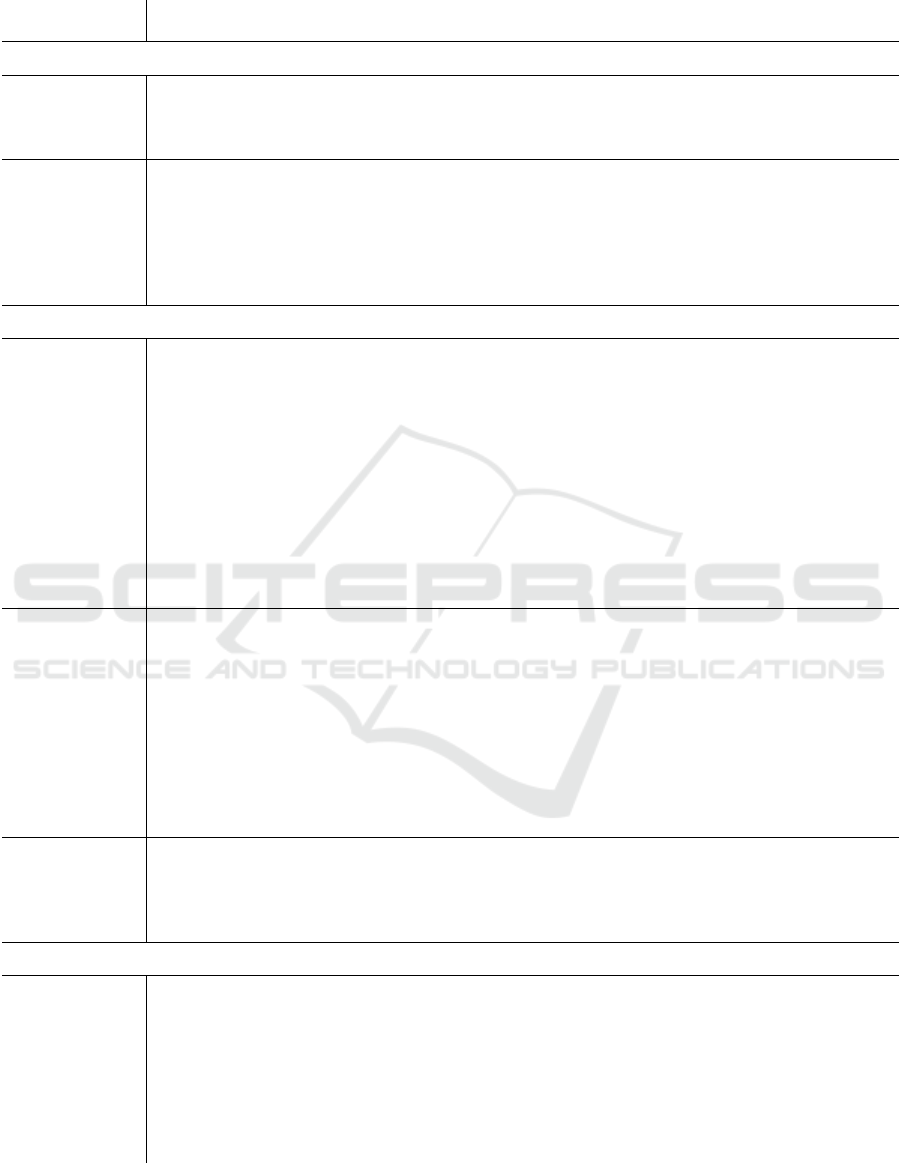

Table 2: Research Instrument.

Stage

Data Collection Instrument

Preparation

Meeting

PrepQ1: What challenges does the IT organization face when supporting both internal and

external customers? … Any benefits?

PrepQ2: What is the role of IT leadership in reducing the reluctance of your IT organization

to integrate innovation?

PrepQ3: What components of the IT Strategy have you considered in order to reduce the

reluctance of the IT organization (Innovation and operation)?

PrepQ4: Can the IT organization be a lever rather than a barrier to radical innovation based on

EIT? How?

Stage 1 “Discovery”

workshop

Exercise 1: During the business model innovation project, identify obstacles, investments

and mechanisms or processes used to address these obstacles and prepare the organization

for the integration of emerging technologies IT. (Answers prefixed by M for mechanisms

& O for obstacles)

Exercise 2: During the business model innovation project, identify reasons why the IT

organization was reluctant to integrate emerging technologies in IT.

Exercise 3: Identify mechanisms that reduced reluctance of your IT organization to

integrate innovation, consolidate the input from the first exercise to derive deeper feedback.

Concluding Question S1: How can the IT organization be a lever rather than a barrier to

radical innovation based on emerging technologies in IT?

Stage 2 - Saturation

FollowQ1: How do you adopt and institutionalize emerging technologies in IT?

FollowQ2: In the business model innovation project integrating emerging technologies in IT (the

specific project), what issues did you observe in transitioning innovation into operation? In the

project, what were the operational barriers? How did you address them?

FollowQ3: What is the role of IT leadership in reducing the reluctance of your IT Organization

to integrate innovation – in general and relative to this project?

FollowQ4: What components of the IT Strategy have you considered in order to reduce the

reluctance of the IT Organization to integrate Innovation – can you please share a copy of the

strategic plan?

FollowQ5: How were these mechanisms implemented, by whom and what results were seen?

FollowQ6: Can the IT organization be a lever rather than a barrier to radical innovation

based on emerging technologies in IT? How?

Stage 3 - Discussion

Unstructured discussion and feedback workshop for member checking and validation.

Note: This paper is part of a larger outcome of a developed study. For completeness, the instrument above is presented in its

entirety with relevant questions to this paper highlighted in bold.

Table 3: Key codes related to the seed concept of Knowledge acquisition (Partial results related to this seed concept).

Key Code

Empirical Statements (Parenthetic numbers indicate the frequency of occurrence in the statements

and prefixes indicate a reference to the data collection instrument)

Concept: Knowledge Acquisition

Acquire new

knowledge

(Roberts et al.,

2012)

O3.1.B “Acquire new knowledge internally and reduce the reliance on suppliers

O1.2.A “Develop awareness about alternative solutions through research and library searches (2)

PrepQ2.A5: “Learning capabilities, collaboration and internal information exchange through the

training and cross training of technical staff.

Seek external

knowledge

(Pugh &

Prusak, 2013)

M7.1.A “Hired an external consultant to provide workshops for requirements definition and draft an

initial plan to implement these requirements

M3.2.B “Identify key providers and setup joint R&D teams with them

M5.1.B “Setup R&D efforts with peer organizations, key partners and suppliers.

M4.2.B “Review and research other implementations in peer organizations

M3.2.A Started architectural review session emphasizing the role of external consultants in order to

insource the required knowledge

Concept: Knowledge Transfer

Transfer

acquired

knowledge

(Alavi &

Leidner, 2001;

Gatewood,

2009)

O1.5.B “Establish regular (bi-weekly) knowledge sharing sessions”.

O1.4.B “Setup a database of training materials”

O1.3.B “Setup knowledge management systems that may reduce the cost of individual training for

each of the team members and allow for information sharing”

M1.4.A “Perform many user training sessions and develop easy to use users’ manuals

PrepQ2.B5 “Knowledge transfer tactics between the teams … the sorting and categorization of

information with knowledge management systems”…

PrepQ2.A5 “At some opportunities, an extended staff meeting would be necessary to synchronize the

information and normalize it across the IT organization”.

S1.B2 “Share IT knowledge across the IT organization

S1.B4 “The organization shares business decisions with all technical employees

FollowQ6.A7. “… knowledge acquisition is the basis of everything… all means of knowledge

acquisition and sharing should be leveraged.”

Training

activities

(Edwards &

Peppard, 1997;

Roberts et al.,

2012)

M1.1.B “Conduct internal training sessions (train the trainer) and bring the training in-house” (2)

M6.1.B “Training of chosen people assigned to specific technologies”

O5.1.B “Attend conferences to stay ahead of the learning curve”

O1.2.B “Setup labs for the training activities to be carried in-house”

O1.3.A “Training the IT team on technology” (4)

PrepQ2.B5 “provide education and incentive programs related to uptime and resolution time,

PrepQ2.B5… “The teams will undertake in the next few month a training session to update them on

the latest in ITIL from service and support to strategy”

PrepQ2. B5 “First we send them to conference. They will then have a chance to network with peers

and learn, gain the confidence with the technology and come and convey the knowledge internally”.

S1.B3 “Invest in training for products and technologies”

Participation in

decision making

(Jansen et al,

2005; Xue et al.,

2008)

PrepQ2.A5 “With the right analysis – a deep analysis of the potential technology, involving nearly

everyone on the team, while pushing collaboration with experts in building the big picture…”.

PrepQ2.A5 “We need to discuss and consider input from all team members...”

PrepQ2.B5 “In order to keep the IT organization engaged in realizing the objectives, we involved them

in the decisions”

Emerging Concept: Explore the tacit knowledge of the customer

Explore the tacit

knowledge of

the customer

PrepQ1.B5. “The IT support team meets with the IT infrastructure team regularly to review the

customer issues, build the knowledge base and solicit the collaboration of ideas across the technical

team internal and external”.

S1.B6 “Share the lessons learned from solving customer issues with the business. This works as a

feedback into the business of the issues facing IT which may in turn drive a business solution or a new

service”.

FollowQ6.A “we participate in educating customers to increase the enthusiasm at the customer level”

PrepQ4.B “IT organization was a consultant to the customer … the IT team scouted for opportunities

at the customers’ base, and feedback is brought back to the business”