A Motivating Social Robot to Help Achieve Cognitive Consonance

During STEM Learning

Khaoula Youssef

1

, Walid Boukadida

2

and Michio Okada

1

1

Toyohashi University of Technology, Toyohashi, Japan

2

College Ibnou Sina, Msaken, Tunisia

Keywords:

Anxiety, Learned Helplessness, Motivation, Social Agency, Cognitive Consonance.

Abstract:

In this paper, we show that cognitive consonance could be measured using the perceived cognitive consonance

questionnaire that we present in this paper or using three different constructs which are the prospect, anxiety

and learned helplessness. We used different motivating agents and we verified whether the student’s motivation

would increase too. In the second study, we measured the cognitive consonance using the related questionnaire

and the three constructs that we proofed that they help on measuring the cognitive consonance during the first

study. This method is called the triangulation and help us to make sure that the cognitive consonance has truly

increased or not when we manipulate the motivation construct. Finally, since cognitive consonance increased

when we use a motivating agent, we decided to investigate which of three agents (a teacher, a tablet or a robot)

may lead to better motivation outcome and thus may help the student to strive for answering and focusing

on the difficult scientific questions. Results show that using a robot is the best solution that may increase the

student’s motivation and help him/her to adopt a positive attitude change on a long term basis while the student

starts to concentrate on the difficult questions rather than jumping to the easy ones.

1 INTRODUCTION

The field of social robots has grown into an exten-

sive body of literature over the past years, with a

wide variety of approaches for extracting human pat-

terns and modeling robots’ skills. Robots operate as

partners, peers or assistants in a range of tasks such

as with autistic children (Boccanfuso and O’Kane,

2011)(Wainer et al., 2014), at homes

1

, in hospitals

(Bilge and Forlizzi, 2008) or for having fun; e.g: the

robotic toys from Wowwee

2

, etc. Another role that a

robot can play is the role of a motivating agent to do

difficult tasks; e.g: solving a difficult exercise. Mo-

tivating a student may increase the student’s strive

for cognitive closure

3

while doing difficult exercises.

Many studies from HRI tackled the fact of how to

afford the robot with the ability to motivate people

in many application fields such as at school (Szafir

and Mutlu, 2012), as story-tellers (Ham et al., 2015),

or as inciters to conserve energy (Ham and Midden,

2014), etc. Different points were investigated in other

1

Roomba, iRobot:. http://www.irobot.com

2

Limited, WowWee Group. http://www.wowwee.com/

3

The cognitive closure can be defined as the human’s desire

to eliminate ambiguity and arrive at definite conclusions

HRI studies such as the design strategies to improve

patient motivation during robot-aided rehabilitation

(Colombo et al., 2007), the effect of robot appear-

ance types on motivating donation (Kim et al., 2014),

the role of the socially assistive robot in motivating

older adults to engage in physical exercise (Fasola and

Mataric, 2013), etc.

However, to the best of our knowledge no con-

cern was paid to the serious conflicts that students en-

counter at schools while learning science, technology,

engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and the social

robot key motivating role that can be played. The con-

flicts emerging from solving difficult STEM exercises

may lead to an increased anxiety and learned help-

lessness (Fincham et al., 1989). Anxiety refers to the

extent to which an exercise causes fear and reluctance

from the student’s behalf. Learned helplessness refers

to a disruption in motivation, effect and learning when

the students feel they do not have any control of the

outcome.

Consequently, it is important to give a serious at-

tention to the issue of the dangerous consequences of

cognitive conflict while doing a STEM difficult ex-

ercise. Cognitive conflict is a discomfort that one in

general experiences when a student holds beliefs, at-

322

Youssef, K., Boukadida, W. and Okada, M.

A Motivating Social Robot to Help Achieve Cognitive Consonance During STEM Learning.

DOI: 10.5220/0006429003220329

In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Software Technologies (ICSOFT 2017), pages 322-329

ISBN: 978-989-758-262-2

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

titudes or behaviors that are at odds with one another

(the ratio between dissonant and consonant precon-

ceptions about a STEM notion). As a result, we need

to grant the social robot with the ability to follow

closely the student’s engagement and use motivating

strategies that may decrease the cognitive conflict stu-

dents may get through while solving STEM exercises.

In the current research, we investigate how cogni-

tive consonance-related characteristics (i.e., motiva-

tion, prospect

4

, anxiety, and learned helplessness) af-

fect people’s appraisal of cognitive consonance. More

specifically, our main focus is understanding the role

of motivation in the cognitive consonance percep-

tion process. In the first study, employing a large

range of mathematical exercises, we test the relation-

ship between cognitive consonance and the triplet:

prospect, anxiety and learned helplessness. In the sec-

ond study, we examine the role of appraisals of mo-

tivation as they relate to appraisals of prospect, anx-

iety, learned helplessness, and perceptions of cogni-

tive consonance. More specifically, we test whether

the effect of motivation on perceptions of cognitive

consonance is mediated by appraisals of the cognitive

consonance-related characteristics. In the third study,

we complement the correlational approach used in the

second study to understand the role of motivation by

experimentally manipulating agent level’s of agency

and we verify whether it is better to use a human, a

robot or a tablet to better increase the student’s moti-

vation. If the student’s motivation is increased, his

performance during study would increase too. He/

She will have better implicit and explicit attitudes be-

haviors and would be pleased while doing difficult ex-

ercises without jumping from the difficult exercise to

the easy one.

2 BACKGROUND

In our modern-day society, education plays a vital

role. Motivating the student’s while acquiring new

knowledge is one of the most often used strategies

aimed at (re)designing the classroom environment in

such a way as to reduce the poor academic perfor-

mance, lack of motivation for school, loss of interest

in work and poor relationships with peers or teachers.

When cognitive dissonance occurs, different

counter-attitudinal actions can be chosen by the hu-

man and which are: an active attitude change with a

new attitude created

5

, a belief change by minimizing

4

Prospect is typically defined as the extent to which the ex-

ercise’s easiness allows the student to continue resolving

the exercise.

5

The student thinks that he has to change his attitude of

the importance of the cognitive dissonance

6

or a per-

ception change by getting a new information to sup-

port one’s previous decision

7

. When the student ex-

periences cognitive dissonance, he will strive to de-

crease the inconsistency by choosing one of the de-

scribed counter-attitudinal actions. We want that stu-

dents get rid of their bad attitudes of skipping the diffi-

cult STEM exercise. The new formed attitude should

be highly accessed so that it can be stored on a long

term basis on the student’s cognitive miser

8

.

3 FIRST STUDY

3.1 Method

Different groups of participants independently tried to

answer a set of mathematical small questions included

in a quizz and then evaluate exercises either on cogni-

tive consonance-related characteristics (i.e., prospect,

anxiety, and learned helplessness) or on perceived

cognitive consonance. We expected that appraisals

of prospect would be positively associated with per-

ceived cognitive consonance, and that appraisals of

learned helplessness and anxiety would be negatively

associated with perceived cognitive consonance. We

employed a within-subjects design in which partici-

pants evaluated a set of 100 small mathematical ques-

tions. The dependent variables were prospect, anxiety

and the learned helplessness. Our sample comprised

31 participants (15 males and 16 females, Mean(age)

= 16.03, SD(age) = 2.45, with age range [13.5-19.5]

years). The participants were students in Ibnou Sina

College (Figure 2).

3.2 Materials and Measures

The current study comprised 100 mathematical ques-

tions set by an experienced teacher. We measured dif-

ferent components which are the prospect, the anxiety

and the learned helplessness using slight adaptations

of the items used in the literature. The different com-

ponents were each measured using three five-point re-

sponse category format items, ranging, for example,

from (1) ”strongly disagree” through (3) ”neutral” to

(5) ”strongly agree”. We calculated the average of the

different items for each measure and used these ag-

avoiding difficult exercises.

6

After all, science learning is not that important. Many

other tasks could be done.

7

The student thinks that the answer afforded by the book is

incorrect.

8

By measuring the implicit and explicit attitudes, we can

verify whether it was established for a long term basis.

A Motivating Social Robot to Help Achieve Cognitive Consonance During STEM Learning

323

camera

Speaker

microphone

servo

motors

(a)

Denial gesture

Back

Forward

Right

Left

Conrmation

gesture

Disappointement

gesture

(b)

Figure 1: (a) A close-up picture of ROBOMO; (b)

ROBOMO overall design.

Current question Next question

Figure 2: The first study overall experiment setup.

gregate scores in our analyses (α

cognitive

c

onsonnance

=

.91, α

prospect

= .95, α

anxiety

= .69 and

α

learned

h

elplessness

= .79.

3.3 Results and Discussion

All of the reported analysis are performed on the ag-

gregate measure scores for each mathematical ques-

tion across all participants. Descriptives for the

measures of our dependent variables are presented

in Table 1. We first examined correlations be-

tween cognitive consonance and the measures of the

consonance-related characteristics (prospect, anxiety,

learned helplessness) (Table 2). As expected, per-

ceived cognitive consonance was positively corre-

lated with prospect (r = .71, p ≤ .001), and nega-

tively correlated with anxiety (r = -.65, p ≤ .001) and

learned helplessness (r =-.85, p ≤ .001). These re-

sults show that appraisals of prospect, anxiety, and

learned helplessness are highly associated with the

perception of cognitive consonance even when the

ratings of perceived cognitive consonance and the

cognitive consonance-related situation characteristics

are obtained independently from each other. Next,

we examined the correlations among the measures of

the cognitive consonance-related characteristics (Ta-

ble 2). Prospect was negatively correlated with anxi-

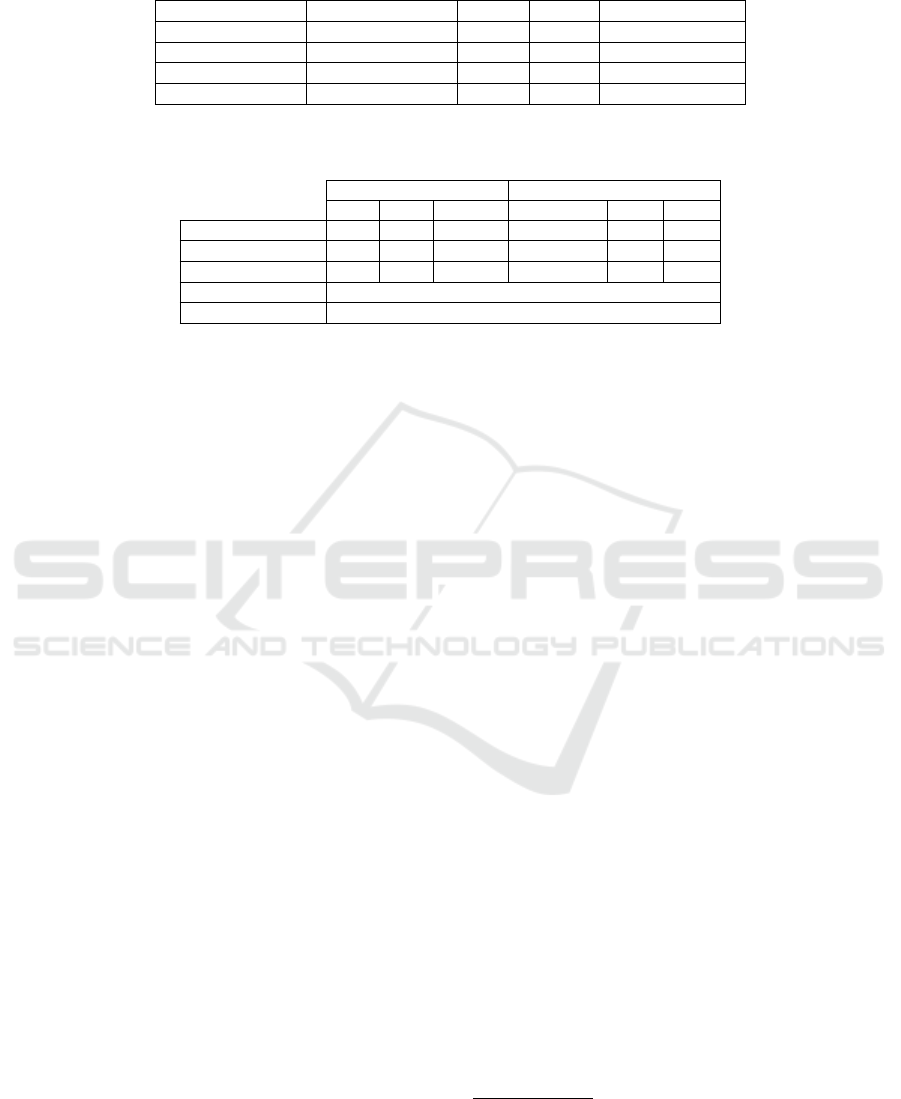

Table 1: Descriptives for the measures of cognitive conso-

nance, prospect, anxiety, and learned helplessness.

M SD Min Max

Cognitive Consonance 3.16 0.70 1.25 4.31

Prospect 2.84 0.71 1.25 4.22

Anxiety 3.12 0.55 1.98 4.56

Learned Helplessness 3.23 0.63 2.04 4.87

ety (r = -.83, p ≤ .001) and learned helplessness (r =

-.72, p ≤ .001), and anxiety was positively correlated

with learned helplessness (r = .73, p ≤ .001).

Next, we used multiple regression analysis to

test whether appraisals of the cognitive consonance-

related situation characteristics (prospect, anxiety,

learned helplessness) predicted appraisals of per-

ceived cognitive consonance. We found that the

three predictors accounted for approximately 75% of

the variance in perceived cognitive consonance with

F(3,96) = 94.77, p ≤ .001, R

2

= .75, and R

2

ad j

=

.74. As expected, appraisals of both anxiety and

prospect significantly predicted perceived cognitive

consonance (Table 3). Anxiety was not found to pre-

dict perceived cognitive consonance to a significant

extent (Table 3).

One problem with multiple regression analysis

is that they fail to appropriately partition the vari-

ance when the predictors in the model are highly

correlated. Thus, an assessment of the relative con-

tribution of the three predictors to cognitive conso-

nance evaluation characteristics

9

was impeded by the

high multi collinearity between these predictor vari-

ables in our data (Table 2). Hence, we employed

the rego

2

package, available for Stata, that utilizes

Shapley value decomposition to decompose the over-

all model goodness-of-fit index (in our case R

2

) into

independent contributions of the predictor variables.

While appraisals of anxiety were not found to sig-

nificantly predict perceived cognitive consonance in

our multiple regression analysis, the results from the

R

2

decomposition revealed that anxiety contributed

only slightly less to the overall variance as compared

to prospect (Table 3). In line with the multiple re-

gression analysis, the results of the R

2

decomposition

indicated that of the three predictors in our model,

appraisals of learned helplessness contributed most

strongly to the overall variance. We tested the robust-

ness of our regression model by performing 100 split

9

Cognitive consonance characteristics evaluation is ac-

counted for by prospect (perceived student’s desire to con-

tinue with solving the mathematical exercises), anxiety

(perceived student’s anxiety after solving a mathematical

exercise), and learned helplessness (a situation in which

a student believes that his efforts are going for waste and

that he got a problematic cognitive problem that prevent

him from understanding mathematics).

ICSOFT 2017 - 12th International Conference on Software Technologies

324

Table 2: Correlations between measures of cognitive consonance, prospect, anxiety, and learned helplessness (Note ***

p ≤ .001).

Cognitive Consonance Prospect Anxiety Learned Helplessness

Cognitive Consonance -

Prospect .71*** -

Anxiety -.65*** -.83*** -

Learned Helplessness -.85*** -.73*** -.73*** -

Table 3: OLS multiple regression results with the decomposition of R

2

(in % of total R

2

). Lower level (LLCI) and upper level

(ULCI) confidence intervals based on bootstrapping with 5000 resamples.

Multiple Regression Decomposition of R

2

Beta t p Shapley %R

2

LLCI ULCI

Prospect 0.26 2.71 0.008 25.58 18.14 32.3

Anxiety 0.12 1.26 0.211 19.1 13.04 27.2

Learned Helplessness -0.75 -9.49 p ≤.001 55.32 43.64 67

Observations 100

Full model R

2

0.75

sample validations. In each instance, the original

100 stimuli were randomly assigned to two groups of

equal size. The regression weights of prospect, anx-

iety, and learned helplessness obtained from a multi-

ple regression analysis on the first group, were then

used to calculate predicted scores for perceived cog-

nitive consonance of the second group. In the last

step, the correlation between the observed scores and

the predicted scores for the second group was calcu-

lated. The results show a high robustness of our re-

gression model across the 100 split sample validations

(M

r

= .86, SD

r

= .033, M

R

2

= .74).

Across our large sample of representative envi-

ronments, our regression model, predicting perceived

cognitive consonance from appraisals of prospect,

anxiety, and learned helplessness accounted for ap-

proximately 75% of the variance in cognitive con-

sonance judgments. The model was found to be ro-

bust across 100 split sample validations. As expected,

both prospect and anxiety were identified as signif-

icant predictors of perceived cognitive consonance.

Moreover, our findings are in line with previous find-

ings indicating that appraisals of learned helplessness

are most strongly associated with perceived cognitive

consonance. In contrast to previous findings, anxiety

was not found to make a significant contribution to

perceived cognitive consonance in our model.

4 SECOND STUDY

We extended our investigation to the role of a mo-

tivating agent’s presence in the cognitive consonance

appraisal process by including participants’ appraisals

of the agent in our regression model. Our goal is to

enhance the student’s academic skills. We assumed

that the presence of a motivating agent that may con-

vince the student to continue resolving the difficult

STEM exercise even when he/she faces a cognitive

dissonance situation, may enhance the student’s ap-

preciation of the STEM (science, technology, engi-

neering and mathematics) subjects. The agent is sup-

posed to encourage the student to achieve the task of

answering the mathematical set of questions. In gen-

eral, when a student faces a difficult STEM exercise

and he/she finds out that his/her answer is incorrect,

he/she will jump to the next exercise by adopting a

belief change as a counter-attitudinal behavior. If he/

she opts for redoing the exercise that was previously

answered incorrectly without putting so much effort

while redoing it so that he/she gets to the correct an-

swer, we say that the student chooses a perception

change as a counter-attitudinal behavior. We want that

the student chooses the attitude and behavior change

as a counter-attitudinal behavior after being stricken

by the cognitive dissonance, so that he/she learns ef-

ficiently the STEM subjects. We used different types

of agents that may help the student to overcome the

cognitive dissonance which are: a friend (of the same

age), a teacher, a robot (ROBOMO), a tablet. The

different agents use three different mixed strategies to

motivate the student which are the door in face

10

and

labeling techniques.

We expect that, an enlightening motivating agent

may empower the student to make an easy shortcut,

reduce the cognitive workload and follow the mo-

tivating message’s guidelines consisting on redoing

the STEM question that was previously answered in-

correctly rather than adopting a perception or belief

10

Here, we need to start by an inflated request and then re-

treat to a smaller request. After the first request is refused,

the human will feel that he/she needs to change his/her

opinion since the initial request has changed (a matter of

reciprocity).

A Motivating Social Robot to Help Achieve Cognitive Consonance During STEM Learning

325

change strategies.

The general aim of the second study is to exam-

ine the path through which appraisals of the motiva-

tion afforded by the agent in a situation that leads

to a cognitive dissonance, affect people’s apprecia-

tion and cognitive consonance. We employed a sim-

ilar design as the previous study and asked partici-

pants to evaluate the different motivating agents that

were combined with the set of mathematical questions

used in the previous study. We assign randomly for

each question one of the 3 different agents. Follow-

ing previous findings from the literature, we expected

to find that appraisals of the motivating agents would

be positively associated with the appraisals of the cog-

nitive consonance obtained in the previous study. We

expected that this effect of perceived motivation af-

forded by the agent on perceived cognitive conso-

nance would, at least partially, be mediated by the ef-

fect of perceived motivation afforded by the agent on

the cognitive consonance-related characteristics (i.e.,

prospect, anxiety, and learned helplessness).

4.1 Method

We employed a within-subjects design in which par-

ticipants evaluated the perceived motivation afforded

by the agent while they are resolving the mathemati-

cal questions. The sample comprised 46 participants

(22 males and 24 females, M

age

= 30.37, SD

age

=

14.51, age range = 18 - 62 years). The participants

were registered in Ibnu Sina College.

4.2 Materials and Measures

We used the same set of mathematical questions used

in the previous study. Perceived motivation afforded

by the agent was measured using different five-point

response category format items ranging, for example,

from (1) ”Not interested” through (3) ”neutral” to (5)

”Interested”

11

. We calculated the average of the items

for each mathematical question and used this aggre-

gate score in our analysis (α = .87).

4.3 Procedure

The procedure and conditions of the second study

were analogous to those of the previous one, except

that while answering each question of the mathemati-

cal quizz, an agent speaks out loud a motivating mes-

sage so that we can ensure that the student keeps on

answering the quizz even if the questions are difficult.

In fact, if the question is difficult and the student rec-

ognizes that his answer is incorrect, he may feel dis-

11

https://goo.gl/forms/PYTnJLe44mIMkJN12

appointed. His mathematical preconceptions are de-

feated and he experiences a discrepancy between

what he believes and the answer. In such a case,

a successfully motivated student would answer the

same question that was previously answered incor-

rectly. All participants responded to the items of the

perceived motivation questionnaire.

4.4 Results and Discussion

We added the aggregated perceived motivation af-

forded by the agent measure’s score as a new vari-

able to the data set containing the prospect, anxiety,

learned helplessness, and perceived cognitive conso-

nance obtained in the previous study. Descriptives for

the measure of perceived motivation afforded by the

agent measure are presented in Table 4. We first ex-

amined the correlations between the perceived moti-

vation afforded by the agent’s measure and the mea-

sures from previous study (Table 5). We found that

perceived motivation afforded by the agent was posi-

tively correlated with perceived cognitive consonance

(r = .47, p ≤ .001) and prospect (r = .76, p ≤ .001),

and negatively correlated with anxiety (r = -.48, p ≤

.001) and learned helplessness (r = -.49, p ≤ .001).

To test whether appraisals of the perceived moti-

vation afforded by the agent predicted appraisals of

perceived cognitive consonance, we performed a re-

gression analysis. The regression model accounted

for approximately 20% of the variance in perceived

cognitive consonance with F(1,98) = 27.28, p ≤ .001,

R

2

= .22, and R

2

ad j

= .21. As expected, perceived mo-

tivation afforded by the agent was significantly related

to perceived cognitive consonance (β = .48, t = 5.22,

p ≤ .001). The regression model was moderately ro-

bust across 100 split sample validations (M

r

= .48,

SD

r

= .079, M

R

2

= .22).

Next, a multiple regression analysis was con-

ducted with both the perceived motivation afforded by

the agent and the cognitive consonance-related char-

acteristics (prospect, anxiety, learned helplessness)

as predictors. The combination of measures signifi-

cantly predicted perceived cognitive consonance with

F(4,95) = 72.31, p ≤ .001, R

2

= .75, and R

2

ad j

=

.74. However, while the measures of the cognitive

consonance-related characteristics predicted signifi-

cantly over and above the perceived motivation af-

forded by the agent measure with R

2

change = .54,

F(3, 95) = 68.53, p ≤ .001, the perceived motivation

afforded by the agent measure did not predict signif-

icantly over and above the measures of the cognitive

consonance-related characteristics with R

2

change =

.01, F(3, 95) = 1.99, p = .161. Based on these results,

perceived motivation afforded by the agent appears to

ICSOFT 2017 - 12th International Conference on Software Technologies

326

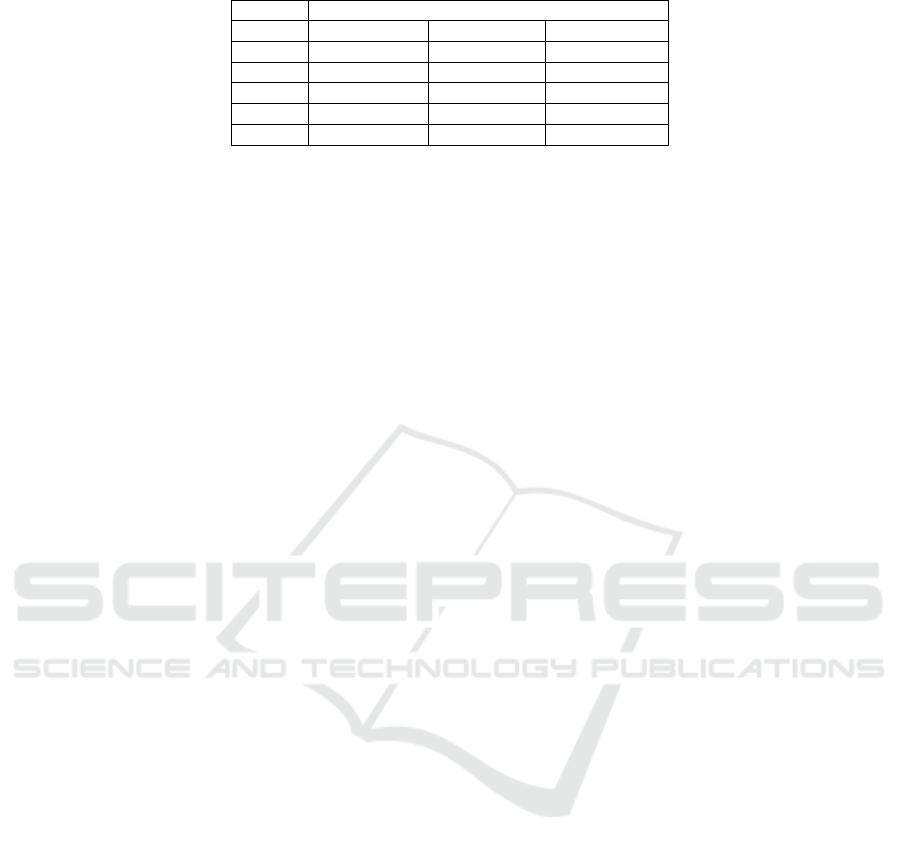

Table 4: Descriptives for the measure of perceived motivation afforded by the agent.

M SD Min Max

Perceived motivation afforded by the agent perceived motivation afforded by the agent 2.91 0.69 1.26

Table 5: Correlations between the measures of perceived perceived motivation afforded by the agent of the current study and

the measures cognitive consonance, prospect, anxiety, and learned helplessness of the previous study. *** p ≤.001.

Perceived Consonance Prospect Anxiety Learned Helplessness

Perceived motivation afforded by the agent .47*** .76*** -.48*** -.49***

Table 6: Summary of mediation analysis results. 95% confidence intervals based on bootstrapping with 5000 resamples.

Reported confidence intervals are bias corrected. *** p ≤.001

Independent variable total effect direct effect mediator a b indirect effect LLCI ULCI

Perceived motivation afforded by the agent .476*** -0.127 prospect .787*** .41*** 0.322 0.103 0.593

anxiety -.381*** 0.241 -0.092 -0.24 0.02

learned helplessness - .447*** -.833*** 0.372 0.214 0.574

offer little additional predictive power beyond that

contributed by appraisals of prospect, anxiety, and

learned helplessness.

While our results show that appraisals of the

perceived motivation afforded by the agent are in-

deed associated with perceived cognitive consonance,

the lack of predictive power over the cognitive

consonance-related characteristics and the medium to

high correlations between perceived motivation af-

forded by the agent and the cognitive consonance-

related characteristics suggest that this association

may be mediated by changes in appraisals of prospect,

anxiety, and learned helplessness. We used the boot-

strapping method for multiple mediation by Preacher

and Hayes (Kristopher and Hayes, 2008) to test

whether the effect of perceived motivation afforded

by the agent on perceived cognitive consonance was

mediated by appraisals of the cognitive consonance-

related characteristics. See Table 5 for a summary of

the results of our mediation analysis.

The results of the mediation analysis show that

perceived motivation afforded by the agent is posi-

tively related to prospect, and negatively related to

anxiety and learned helplessness. Our results also

confirm the multiple regression analysis, showing that

perceived motivation afforded by the agent (total ef-

fect), prospect and anxiety were significantly related

to perceived cognitive consonance. The bootstrapping

method provides estimates and bias corrected confi-

dence intervals for the indirect effects in the model.

If the confidence intervals do not contain zero, the

estimate of the indirect effect is significant. Fol-

lowing this criterion, the results show that both the

indirect effect of prospect and anxiety were signifi-

cant. The indirect effect of anxiety was not signif-

icant. Importantly, our results show that if we ac-

count for the relation between perceived motivation

afforded by the agent and appraisals of the cognitive

consonance-related characteristics, the effect of per-

ceived motivation afforded by the agent on perceived

cognitive consonance (direct effect) is no longer sig-

nificant, suggesting that this effect is fully mediated

by changes in appraisals of prospect and anxiety.

In sum, our results show that while perceived mo-

tivation afforded by the agent significantly affects the

perceived cognitive consonance. These findings pro-

vide evidence for the idea that the motivation afforded

by the agent (friend, robot, teacher, tablet) influences

cognitive consonance perceptions indirectly through

its effect on those cognitive consonance characteris-

tics (prospect, anxiety and learned helplessness) that

are important for the cognitive consonance appraisal

process.

5 THIRD STUDY

As motivation has a direct effect on the cognitive con-

sonance and we have opted to use different agents in

the previous study (study 2). We decided to verify

which of the three different agents type may lead to

the highest motivation perception.

5.1 Method

66 Tunisian students participated in this experiment

([17-19] years) from Farhat Hached College. Par-

ticipants were debriefed which may help us to eval-

uate their planned attitude

12

. Participants were told

that they would resolve some exercises to help eval-

uate a new robot platform. Once a student enters to

the room, he/she was asked to do the calibration (eye

tribe) and then starts answering the exercises. We in-

form the student that he/she can choose to jump to the

next exercise if the current one is difficult. When the

12

This is to measure the student’s explicit attitude. We just

ask respondents to think about and report their attitudes.

A Motivating Social Robot to Help Achieve Cognitive Consonance During STEM Learning

327

Table 7: A table showing the second main effect investigation results (tablet vs robot; tablet vs human and robot vs human).

Factor Comparison contrast (F, p-value)

Tablet vs robot Tablet vs human Robot vs human

Pleasure (149.3,<0.001)R (16.34, 0.06) (83.58, <0.001)R

IAT (21.92,<0.001)R (37.54,0.003)H (2.29, 0.013)R

Cog.Diss (136.8,<0.001)R (17.9,<0.001)H (88.5,0.04)R

Quotient (26.09,<0.001)R (5.17,0.049)H (2.6, 0.009)R

Looks (84.4,<0.001)R (54,0.008)H (71.08, <0.001)R

student feels that he/she wants to leave the room

or when he/she finishes the exercises’ collection,

we thank him/her and he/she has to answer a post-

experiment survey. We divided our participants

(within subjects design experiment) in a way that we

can guarantee that we have a counterbalance of the

data, thereby reducing the effect of the sequence of

trials on the results.

ROBOMO generates the motivating speech that it

is coordinated with the robot’s convenient gestures

(body and head gestures) and the right tone. The moti-

vating speech used by the different types of agents fol-

lows the technique labeling technique. As a reminder,

the labeling technique involves assigning a label to the

individual and then requests a favor that it is consis-

tent with the label. For example telling to a student: I

know you are striving to success and deep inside you

are hard worker. In such case, the student has more

tendency to live up with the positive label. Thus, one

way to make a human produce the desired behavior

is to assign positive label to him/her so that you can

drive him/her to live up with that label and maintain

that positive consistency that serves the public image

of the person as well as his/her self-esteem. There are

four conditions the student takes part in which are:

the baseline condition (No motivating message is af-

forded), condition 1 (the tablet affords the motivating

message), condition 2 (the robot affords a motivating

message) and condition 3 (the human affords a moti-

vating message). Each two days, the student comes to

the classroom to redo another set of questions with a

new set of motivating messages while we change the

motivating source.

5.2 Materials and Measures

After the experiment finished, the student has to an-

swer questionnaires such as the explicit attitude (Pan-

tos and Perkins, 2013), the implicit attitude (implicit

association test): IAT (Pantos and Perkins, 2013), the

cognitive dissonance (cogn.diss) (Levin et al., 2013)

and the perceived pleasure’s level(Bradley and Lang,

1994). We considered other dependent variables:

• The quotient: Number of times the user redoes

incorrect question by the number of times the user

makes an error. It gives an idea about when has

the student a tendency to redo incorrect questions

to strive for science learning rather than jumping

from one question to another.

• Looks: number of times the user ”dwells” with

eye gaze between the 2 questions.

5.3 Results and Discussion

The motivating message source agency’s level had

a main effect in terms of all the constructs with

a P-value <0.001. Table7, shows that there were

significant differences between the robot and tablet

conditions with higher results in the robot’s condi-

tion for all the constructs. Also, Table7 shows that

using a robot as a motivating source in compari-

son to using a human increases cog.diss: ((F=88.5,

p-value=0.04<0.05)R) and looks: ((F=71.08, p-

value<0.001)R). There were statistical differences

in terms of pleasure with higher results in the

robot’s condition rather than in the human’s con-

dition ((F=83.58, p-value<0.001)R), IAT ((F=2.29,

p-value=0.013<0.05) R) and quotient ((F=2.6, p-

value=0.009<0.01)R).

6 CONCLUSION

Motivating a student is commonly associated with a

positive effect on the experience of cognitive conso-

nance. Yet, little is known about the psychological

processes through which perceived motivation may

exert its influence on people’s cognitive consonance

perceptions. We investigated the role of motivation in

cognitive consonance perception using a wide range

of different agents types. Across two studies, we

tested the idea that motivation influences appraisals of

cognitive consonance through its effect on appraisals

of cognitive consonance-related characteristics (i.e.,

prospect, anxiety, and learned helplessness). The

more an agent motivates the student, the more he/she

gets clear ideas and scores high in terms of cognitive

consonance. Finally, we compared different agents

types to verify which one of them may lead to better

motivation and thus higher cognitive consonance. Re-

sults show that using a robot may lead to better results

ICSOFT 2017 - 12th International Conference on Software Technologies

328

in terms of perceived motivation. Thus, the students

having a robot as a motivating source adopt a posi-

tive counter-attitudinal behavior (attitude and behav-

ior change) while they strive to answer the STEM

questions that were previously answered incorrectly.

REFERENCES

Bilge, M. and Forlizzi, J. (2008). Robots in organizations:

The role of workflow, social, and environmental fac-

tors in human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the

3rd ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human

Robot Interaction, pages 287–294. ACM.

Boccanfuso, L. and O’Kane, J. M. (2011). Charlie: An

adaptive robot design with hand and face tracking for

use in autism therapy. International Journal of Social

Robotics, pages 1–11.

Bradley, M. and Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion:

the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differ-

ential. Journal of behavior therapy and experimental

psychiatry, 25(1):49–59.

Colombo, R., Pisano, A., Mazzone, C., Delconte, S.,

Micera, K., Carrozza, M., Chiara, P., and M., G.

(2007). Design strategies to improve patient motiva-

tion during robot-aided rehabilitation. Journal of Neu-

roEngineering and Rehabilitation, 4(1):3.

Fasola, J. and Mataric, M. (2013). Socially Assistive Robot

Exercise Coach: Motivating Older Adults to Engage

in Physical Exercise, pages 463–479. Springer Inter-

national Publishing.

Fincham, F., Hokoda, A., and Sanders, R. (1989). Learned

helplessness, test anxiety, and academic achieve-

ment: a longitudinal analysis. Child Development,

60(1):138–145.

Ham, J., Cuijpers, R., and Cabibihan, J. (2015). Combining

robotic persuasive strategies: The persuasive power of

a storytelling robot that uses gazing and gestures. In-

ternational Journal of Social Robotics, 7(4):479–487.

Ham, J. and Midden, C. J. (2014). A persuasive robot to

stimulate energy conservation: The influence of pos-

itive and negative social feedback and task similarity

on energy-consumption behavior. International Jour-

nal of Social Robotics, 6(2):163–171.

Kim, R., Moon, Y., Choi, J., and Kwak, S. (2014). The ef-

fect of robot appearance types on motivating donation.

In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM/IEEE International

Conference on Human-robot Interaction, pages 210–

211, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Kristopher, J. and Hayes, A. (2008). Asymptotic and re-

sampling strategies for assessing and comparing in-

direct effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior

Research Methods, 40(3):879–891.

Levin, D., Adams, J. A., Harriott, C., and Zhang, T. (2013).

Cognitive dissonance as a measure of reactions to

human-robot interaction. Journal of Human-Robot In-

teraction, 2(3):3–17.

Pantos, A. and Perkins, A. (2013). Measuring implicit

and explicit attitudes toward foreign accented speech.

Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 32(1):3–

20.

Szafir, D. and Mutlu, B. (2012). Pay attention!: Designing

adaptive agents that monitor and improve user engage-

ment. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on

Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 11–20,

New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Wainer, J., Robins, B., Amirabdollahian, F., and Dauten-

hahn, K. (2014). Using the humanoid robot kas-

par to autonomously play triadic games and facili-

tate collaborative play among children with autism.

IEEE Transactions on Autonomous Mental Develop-

ment, 6(3):183–199.

A Motivating Social Robot to Help Achieve Cognitive Consonance During STEM Learning

329