Screening and Evaluation Platform for Depression and Suicidality in

Primary Healthcare

Fernando Cassola

1

, Alexandre Costa

1

, Ricardo Henriques

1

, Artur Rocha

1

, Marlene Sousa

2

,

Pedro Gomes

2

, Tiago Ferreira

2

, Carla Cunha

2

and João Salgado

2

1

INESC TEC - INESC Technology and Science, Porto, Portugal

2

ISMAI - Instituto Universitário da Maia, Maia, Portugal

Keywords: Web-based Platform, Decision Support, Screening, Healthcare, Depression, Suicide.

Abstract: This work presents a screening and evaluation platform for depression and suicidality that has been tested in

the scope of primary healthcare. The main objective is to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of screening

processes. A web-based, decision support platform was provided for qualified healthcare professionals. The

platform provides several assessment tools for patient evaluation and monitoring of their treatment, along

with follow up appointment management. A preliminary evaluation process was carried out to understand the

health professional’s satisfaction. This revealed there was general satisfaction with its integrated functions

and all the provided methods of assessment. In conclusion, the project sustains the goal of improving the

treatment outcomes for clinical depression by refining the screening methods and consequently increase the

screening effectiveness and efficiency.

1 INTRODUCTION

Available data indicates that the time period elapsed

between the first depressive episodes and the

respective diagnose by a clinician is about 4 years

(Almeida et al., 2013). Additional references

(Farvolden, McBride, Bagby, & Ravitz, 2003)

suggest that general practitioners fail to diagnose up

to half of the cases of major depressive disorder or

anxiety. On the other hand, depression is associated

with suicide, medical illness and increased risk of

accidental death (Fawcett, 1993).

Screening tools may help physicians and other

health professionals in primary health care to timely

recognize and adequately follow depressive disorder

and suicidality cases. The Stop Depression project

aims at aiding healthcare professionals in this task, in

order to provide a better response to the previously

identified weaknesses.

The StopDepression (“Stopdepression.pt,” 2017)

project (EEA GRANT 91SM3), supported by the

EEA Grants Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway, is a

mental health project deployed in a primary care

setting (ACeS – Agrupamento de Centros de Saúde

do Porto Ocidental - Portugal). The main goal is to

improve the effectiveness of the means used for

detecting depression and managing the risk of

suicide. It’s an initiative inspired by the stepped care

model (Williams & Martinez, 2008) which has

specific objectives: detecting depression in early

stages, assessing suicide risk and improving the

patient’s treatment progress - based on web

technologies - always considering the severity and

symptomatology of each case.

To achieve these goals, a set of training sessions,

complemented by computer-based tools were

delivered to professionals. These have been applied

to face-to-face appointments to systematically

diagnose and thoroughly follow up the treatment of

depression. This paper describes the main software

pieces in the Stop Depression platform and how they

orchestrate in a computer aided diagnosis and

decision support solution.

2 RELATED WORK

In the last decades, several health organizations (e.g.,

United States Preventive Services Task Force

[USPSTF], 2002, 2016; World Health Organization

210

Cassola, F., Costa, A., Henriques, R., Rocha, A., Sousa, M., Gomes, P., Ferreira, T., Cunha, C. and Salgado, J.

Screening and Evaluation Platform for Depression and Suicidality in Primary Healthcare.

DOI: 10.5220/0006369002100215

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2017), pages 210-215

ISBN: 978-989-758-251-6

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

(World Health Organization, 2012); National

Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [NICE],

2009), have been drawing attention to the importance

of improving detection and management of mental-

health problems such as depression.

One way to do this is by performing a systematic

screening and assessment of mental-health problems

in order to promote their adequate treatment (Siu et

al., 2016).

In this context, web-based screening platforms are

being developed and increasingly used for a variety

of mental-health problems (including depression and

suicidal risk) in various healthcare settings and

populations across the world (Farvolden et al., 2003;

Fothergill et al., 2013; Oromendia, Bonillo, &

Molinuevo, 2015).

For instance, the Web-Based Depression and

Anxiety Test (Farvolden et al., 2003) is a web-based

self-report screening instrument that has been used in

a rehabilitation centre in Toronto to effectively screen

for major depressive disorder and a number of

common anxiety disorders. Through this platform,

the healthcare professional has access to a report that

summarizes the person’s responses to several

questions elaborated according to the DSM-IV

criteria for these disorders (American Psychiatric

Association, 2000), which contributes to the

healthcare professional’s decision about the

diagnostic and treatment of the patients (Farvolden et

al., 2003).

Likewise, the Internet-based Behavioural Health

Screen (BHS) is a screening instrument that has been

developed by Diamond and colleagues (2010) to help

detect mental health problems and suicidal risk in

adolescents and young adults in a North-American

primary care. This tool facilitates healthcare

professionals the administration of several

questionnaires, as well as its interpretation and

integration (Diamond et al., 2010).

Also, the Integrating Mental and Physical

Healthcare: Training and Research (Matcham et al.,

2017) is a screening tool that has been used across two

London National Health Service (NHS) Trusts to help

detect depression, anxiety and the severity of nicotine

dependence in patients with chronic conditions. This

web-based platform helps not only the detection, but

also the management of these mental-health disorders

(Matcham et al., 2017).

A common trait among these platforms is that they

help healthcare professionals to perform screening

and diagnosis by integrating validated paper-based

psychometric measures (e.g., PHQ-9; Kroenke,

Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) that maintain good

psychometric properties when adapted to web-based

versions (van Ballegooijen, Riper, Cuijpers, van

Oppen, & Smit, 2016).

However, to our knowledge, although these

platforms are extremely useful tools, the majority

fails to provide healthcare professionals with case

management support information which is essential

for an effective approach to mental health care

(O’Connor, Whitlock, Gaynes, & Beil, 2009).

In order to pursue this goal, we analysed

requirements in the scope of the national context and

proceeded to the development of a case management

platform, which complements the ones previously

developed (Rocha et al., 2012; Warmerdam et al.,

2012) to support low intensity Internet-based

interventions.

The Stop Depression’s key contributions are: 1)

Integrating the screening and assessment of the

severity of depression and suicidal risk; and 2)

Providing healthcare professionals with suggestions

and guidelines for specific interventions based on the

assessment outcome, according to evidence-based

guidelines preconized by NICE (2010).

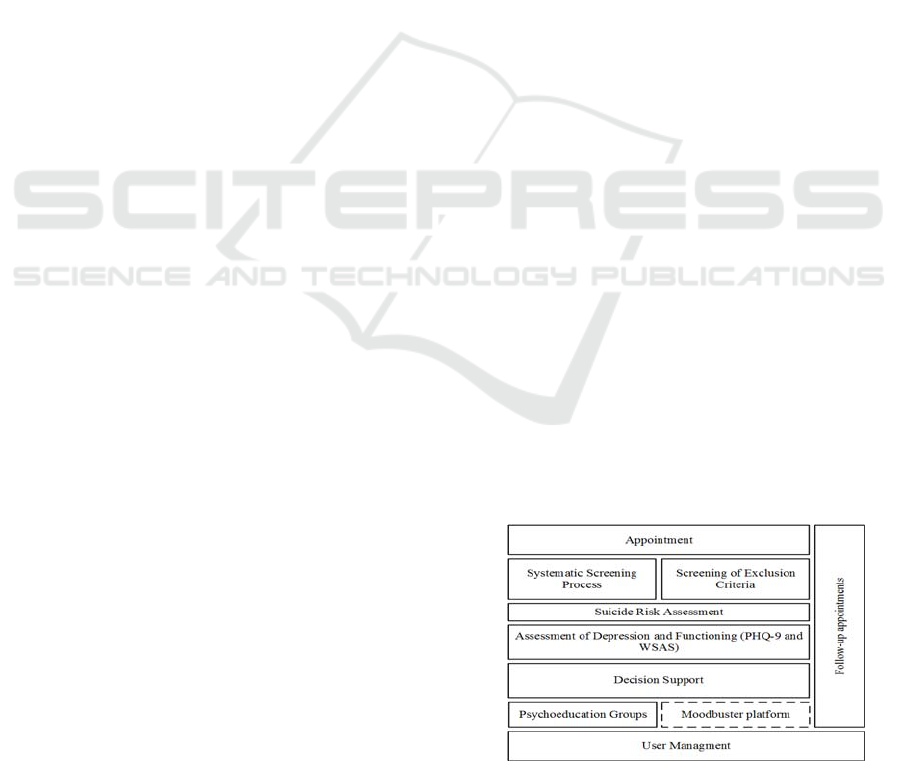

3 DESCRIPTION OF THE

PLATFORM COMPONENTS

The depression and suicidality evaluation platform

records the systematic screening, evaluation and

follow-up of patient’s depressive symptoms. This

takes place during their appointments in the primary

healthcare services. It includes a computer aided

diagnosis and decision support module that leverages

on the input from the remaining modules and its

progress over time to suggest an appropriate course

of action, based on a stepped care model. Figure 1

depicts the logical organization of the software

modules that were developed to achieve these goals.

The following subsections present a brief description

of modules implemented in the context of this project.

Figure 1: Stop Depression platform components.

Screening and Evaluation Platform for Depression and Suicidality in Primary Healthcare

211

3.1 User Management

Stop Depression is a pilot implementation project,

therefore this platform is not yet integrated with

SClínico (“spms.min-saude.pt,” 2017), the software

used by most of the primary healthcare institutions in

Portugal.

In order to deal with this challenge, the platform

includes functionalities to manage multiple user

profiles that are able to interact with different

functionalities. These users include medical doctors

and nurses which are able to screen and evaluate

patients; and psychologists that deliver interventions

to patients assigned to them.

From the technical point of view, an independent

structure was created to hold the subsect of health

records related with the patient mental health. Aside

from dealing with the necessary security issues by

means of authentication and access control over a

secure transport layer, particular attention was paid to

privacy, therefore no information that can directly or

indirectly identify the patient is ever stored.

3.2 Systematic Screening Process

Prior or during an appointment three straight

questions are prompted. Answers to these questions

are used to determine if a more thorough evaluation

should follow. The goal is to quickly detect the

presence of depression and eventual suicidal ideation.

3.3 Screening of Exclusion Criteria

This step narrows a particular disorder or ailments

that prevents the participation of the patient in this

study, such as heavily affected neurocognitive

functions that compromise interpretation abilities,

speech, social interactions and cognition. Psychotic

disorders, including schizophrenia, also fall out of the

spectrum of the study.

3.4 Suicide Risk Assessment

The goal of this process is to weight the factors that

impact the patient’s suicide risk (Jacobs et al., 2003).

The platform is able to draw an inference process to

suggest a treatment course that may address the

patient’s condition. It considers the patient’s

immediate safety as an active measure for critical

cases and suggests urgent procedures if needed.

3.5 Assessment of Depression and

Functioning (PHQ-9 and WSAS)

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

assessment module is used to make a swift but

thorough assessment of the severity of depression and

has been validated for use in primary care services

(Cameron, Crawford, Lawton, & Reid, 2008). The

final score is computed by summing the value of

every answer and indicates the degree of depression.

This questionnaire can also be used to monitor the

patient’s progress recurrently, in order to evaluate

their progress.

Alongside PHQ-9, the patient fills in a

questionnaire aimed at measuring the impairment of

functioning. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale

(WSAS) helps to determine conditions or disorders

that may affect or deteriorate an individual’s abilities

to execute or participate in certain standard day-to-

day tasks (Mundt, Marks, Shear, & Greist, 2002). It

is also used as supplement with PHQ-9 to evaluate the

progress of the patient’s treatment.

3.6 Decision Support

Having completed the interview process, the platform

will show to the interviewer the calculated risk within

the suicide risk scale, which can be used as an aid for

suicide risk assessment. In addition, and depending

on the asserted risk, recommendations and

instructions on how to proceed according to different

degrees of severity are also suggested.

The platform evaluates the severity of depression

based on a weighted analysis of the PHQ-9 and

WSAS. It infers the degree of depression the patient

might have, along with a recommendation on how the

healthcare professional should proceed.

Any outcome presented in this section can’t be

seen as a prognostic, but rather a result of a computer

aided diagnostic tool, that can help the decision of a

qualified healthcare professional. Several important

dimensions not currently taken into account by the

decision support module need to be considered when

assessing depression degrees and suicide risks, such

as, the patient’s current physical state, medical health

history and other psychosocial grades (Williams &

Martinez, 2008).

From the technical perspective it represents a

classification problem. Health professionals have

defined screening rules to rate the patient into disjoint

groups. Said rules form the nodes of a decision-tree

classifier (Silberschatz, Korth, & Sudarshan, 2011).

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

212

3.7 Follow-up Appointments

Healthcare professionals register appointments

periodically, as a treatment monitoring process. This

include the reassessment of the PHQ-9 and WSAS

questionnaires, along with a re-evaluation of the risk

of suicide when necessary. The goal of this module is

to help determining the effectiveness of a treatment

and how well a patient is adapting to it.

3.8 Psychoeducation Groups

Psychoeducation groups are a form of psychotherapy

based on a shared therapeutic experience, which

involves the presence of a therapist, the patient and

other individuals working through similar ailments.

Therefore, group therapy considers the interaction

between group members as a vehicle of change

(Whitfield, 2010), which might play an important role

on the patient’s treatment progress.

The platform allows psychoeducation group

administrators to manage and schedule different

sessions, through the use of a calendar-like interface,

enabling them to choose which schedule best fits the

patient’s need.

3.9 Moodbuster Platform

When a patient is assigned to a computer based

treatment, the system will generate credentials that

allows the user to login on the moodbuster platform.

The moodbuster is an innovative digital solution for

the treatment of depression that is being used in a

follow-up study in a blended care setting. This an

Internet-based depression treatment that “is

considered a promising clinical and cost-effective

alternative to current routine depression treatment

strategies such as face-to-face psychotherapy”

(Kleiboer et al., 2016).

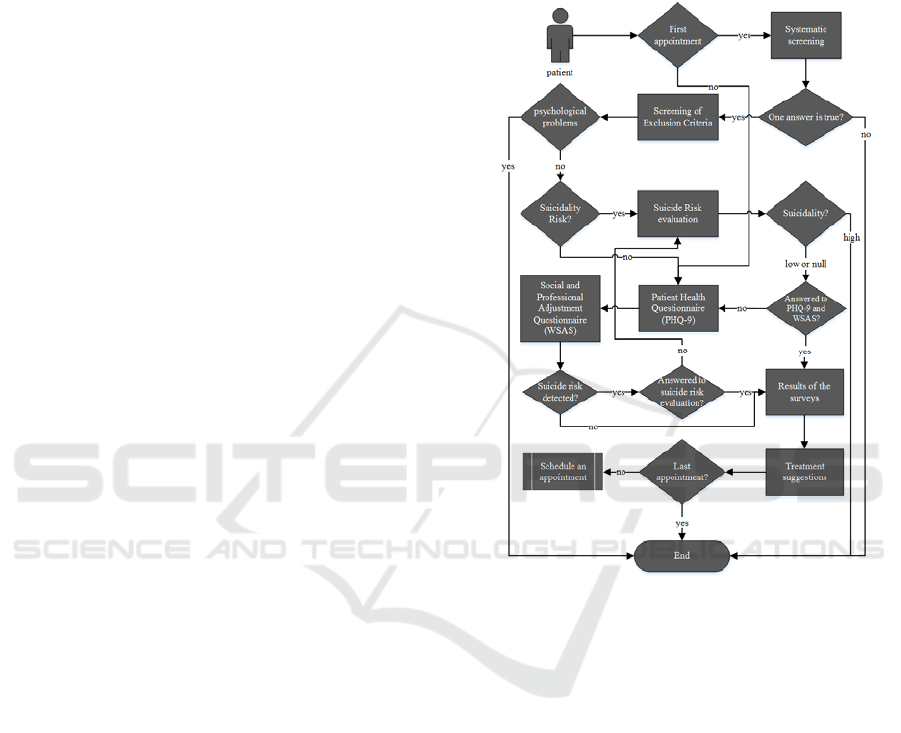

4 PLATFORM WORKFLOW

In the following section we expose the platform’s

workflow, and how appointments progress during an

interview with the patient. Figure 2 shows a

synthesised flowchart of this process.

When a patient attends a medical appointment in

the primary care, a healthcare professional checks for

previous records in the screening and evaluation

platform. If any is present, the professional is required

to repeat the PHQ-9 and WSAS questionnaires

(which may themselves trigger other instruments). On

the other hand, in the case of a first appointment, the

following steps of the screening and evaluation

workflow will happen.

The process begins with the systematic screening,

which may lead to the conclusion that no symptoms

of depression or suicide risk are present, then

resuming to the standard medical appointment.

Figure 2 - Platform Workflow.

If the systematic screening yields a possible

positive result for depression and suicide risk, the

platform will guide the professional through a list of

exclusion criteria. For instance: bipolar disorder,

borderline personality disorder, obsessive-

compulsive disorder, etc., including the suicide risk.

When the professional recognizes that the patient

presents one or more of these exclusion criteria, the

professional will step the patient out of the study,

while recording these results before resuming the

medical appointment.

When excluded due to risk of suicide, the platform

will point out the next steps based on the severity of

that assessment.

If the patient does not meet any exclusion criteria,

the results of PHQ-9 and WSAS instruments are used

to determine the severity of depression and the next

steps of its treatment. These steps also include the

schedule of follow-up appointments to assess the

progress of the patient’s mental health status.

Screening and Evaluation Platform for Depression and Suicidality in Primary Healthcare

213

In either case, the PHQ-9 includes a question to

acknowledge the risk of suicide. If detected, the

suicide risk is then reassessed in all subsequent

appointments.

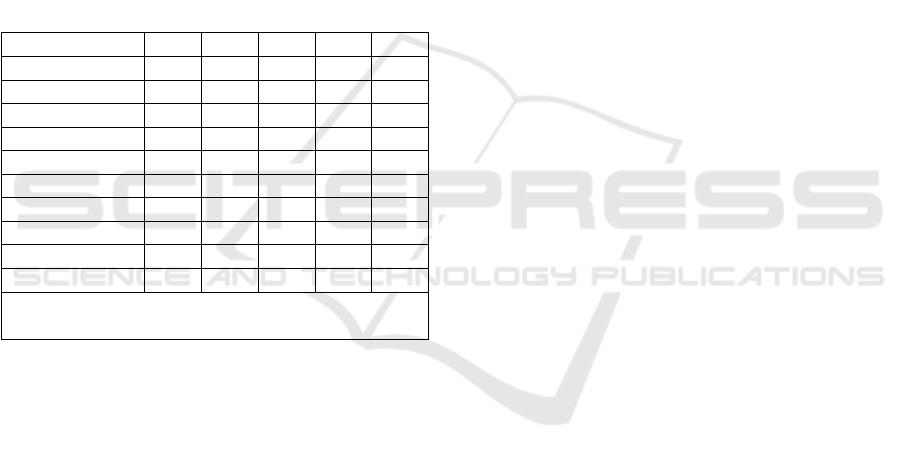

5 PRELIMINARY RESULTS

As a method for analysing user’s satisfaction, a

preliminary evaluation was carried out from a group

of 18 (eighteen) qualified health professionals

answering a System Usability Scale (SUS)

questionnaire (Brooke, 1996). This survey consists of

ten ranked questions that provide a measurement of

effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction regarding

the platform’s use. All participants have received

training in using the platform.

Table 1: SUS results.

a b c d e

Will use frequently 0% 0% 6% 28% 66%

Is complex 33% 39% 11% 17% 0%

Easy to use 0% 0% 6% 44% 50%

Need help to use 44% 33% 17% 0% 6%

Integrated functions 0% 0% 17% 33% 50%

Has inconsistencies 33% 56% 11% 0% 0%

Easy to learn 0% 0% 28% 39% 33%

Is complicated 66% 22% 6% 6% 0%

Felt confidant 0% 0% 16% 56% 28%

Had a learning curve 28% 22% 28% 22% 0%

a- Disagree Completely; b- Disagree; c- Neither Agree nor

Disagree; d- Agree; e- Agree Completely

From the analysis of the collected data (Table 1),

it can be determined that 72% of the users agree that

the platform is easy to learn and 94% of them consider

it easy to use.

Furthermore, most users disagree that the system

had a steep learning curve. In terms of usability, 72%

users disagree that the platform is complex and 88%

disagree that it’s complicated.

A total of 89% of the users disagree that there are

inconsistencies with the user interface.

Most users felt confident interacting with the

platform, with 84% agreeing to this fact. This is

further emphasized by users agreeing that they did not

need help to use the platform, totalling 77%.

When it comes to integrated functions, 73% of the

users were satisfied with the tools provided and the

combined functionalities.

Finally, 94% of the users agreed that they would

definitely use the system frequently.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Stop Depression project’s main goal is to improve

clinical outcome when treating clinical depression. It

does so by broadening the screening process,

allowing early detection of depressive symptoms, and

by refining the treatment course, providing tools for

continuous monitoring of diagnosed patients.

This paper describes a state-of-the-art system for

mental health screening and assessment in the

Portuguese primary care, combining computer aided

diagnostic tools, along with other mechanisms such

as rule-based decision support (Abbasi &

Kashiyarndi., 2006), to empower health professionals

in determining the best treatment course and improve

treatment adherence. New, low intensity

interventions were made available in the scope of this

pilot, with the platform having a determinant role in

their implementation.

System usability surveys reveal that users were

pleased with the use of the system during the Stop

Depression clinical trials. Qualified users considered

the platform to be straightforward and with a low

learning curve, having felt confident while using it.

Moreover, an extremely high percentage of users

claimed that they would use the system frequently.

Although healthcare professionals seem to be

generally satisfied with the platform, more research is

currently undergoing to quantify the gains of using

the system from the clinical perspective.

Furthermore, extending the use of the system to other

institutions, particularly in the primary health care,

will likely require an impact analysis of its

interoperation or integration with the platforms

currently in use by the national health system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper is financed by the ERDF – European

Regional Development Fund through the Operational

Programme for Competitiveness and

Internationalisation - COMPETE 2020 Programme

within project «POCI-01-0145-FEDER-006961»,

and by National Funds through the Portuguese

funding agency, FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a

Tecnologia as part of project

«UID/EEA/50014/2013».

REFERENCES

Abbasi, M. M., & Kashiyarndi., S. (2006). Clinical

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

214

Decision Support Systems: A discussion on different

methodologies used in Health Care. Marlaedalen

University Sweden.

Almeida, J. M. C., Xavier, M., Cardoso, G., Gonçalves

Pereira, M., Gusmão, R., Corrêa, B., … António, J.

(2013). Estudo Epidemiológico Nacional de Saúde

Mental 1

o

Relatório. Faculdade de Ciências Médicas,

Universidade Nova de Lisboa.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and

statistical manual of mental disorders. Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edition TR.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4377-2242-0.00016-X.

Brooke, J. (1996). SUS - A quick and dirty usability scale.

Usability Evaluation in Industry, 189(194), 4–7.

https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20701.

Cameron, I. M., Crawford, J. R., Lawton, K., & Reid, I. C.

(2008). Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS

for measuring depression severity in primary care.

British Journal of General Practice, 58(546), 32–36.

https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp08X263794.

Diamond, G., Levy, S., Bevans, K. B., Fein, J. A.,

Wintersteen, M. B., Tien, A., & Creed, T. (2010).

Development, Validation, and Utility of Internet-

Based, Behavioral Health Screen for Adolescents.

Pediatrics, 126(1).

Farvolden, P., McBride, C., Bagby, R. M., & Ravitz, P.

(2003). A Web-Based Screening Instrument for

Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Primary Care.

Journal of Medical Internet Research, 5(3), e23.

https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5.3.e23.

Fawcett, J. (1993). The morbidity and mortality of clinical

depression. International Clinical Psycho

pharmacology, 8(4), 217–20. Retrieved from

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8277138.

Fothergill, K. E., Gadomski, A., Solomon, B. S., Olson, A.

L., Gaffney, C. A., dosReis, S., & Wissow, L. S. (2013).

Assessing the Impact of a Web-Based Comprehensive

Somatic and Mental Health Screening Tool in Pediatric

Primary Care. Academic Pediatrics, 13(4), 340–347.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2013.04.005.

Jacobs, D. G., Ross Baldessarini, C. J., Conwell, Y.,

Fawcett, J. A., Horton, L., Meltzer, H., … Simon, R. I.

(2003). Practice Guideline for the Assessment and

Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors.

Kleiboer, A., Smit, J., Bosmans, J., Ruwaard, J., Andersson,

G., Topooco, N., … Riper, H. (2016). European

COMPARative Effectiveness research on blended

Depression treatment versus treatment-as-usual (E-

COMPARED): study protocol for a randomized

controlled, non-inferiority trial in eight European

countries. Trials, 17(1), 387. https://doi.org/

10.1186/s13063-016-1511-1.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The

PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure.

Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–13.

Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

pubmed/11556941.

Matcham, F., Carroll, A., Chung, N., Crawford, V.,

Galloway, J., Hames, A., … Hotopf, M. (2017).

Smoking and common mental disorders in patients with

chronic conditions: An analysis of data collected via a

web-based screening system. General Hospital

Psychiatry, 45, 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1016

/j.genhosppsych.2016.11.006.

Mundt, J. C., Marks, I. M., Shear, M. K., & Greist, J. M.

(2002). The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a

simple measure of impairment in functioning. The

British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5).

O’Connor, E. A., Whitlock, E. P., Gaynes, B., & Beil, T. L.

(2009). Screening for Depression in Adults and Older

Adults in Primary Care. Screening for Depression in

Adults and Older Adults in Primary Care: An Updated

Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research

and Quality (US). Retrieved from http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20722174.

Oromendia, P., Bonillo, A., & Molinuevo, B. (2015). Web-

based screening for Panic Disorder: Validity of a single-

item instrument. Journal of Affective Disorders, 180,

138–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.061.

Rocha, A., Henriques, M. R., Lopes, J. C., Camacho, R.,

Klein, M., Modena, G., … Warmerdam, L. (2012).

ICT4Depression: Service oriented architecture applied

to the treatment of depression. In Proceedings - IEEE

Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems.

https://doi.org/10.1109/CBMS.2012.6266379.

Silberschatz, A., Korth, H. F., & Sudarshan, S. (2011).

Database System Concepts - 6th. ed. Database (Vol. 4).

https://doi.org/10.1145/253671.253760.

Siu, A. L., Bibbins-Domingo, K., Grossman, D. C.,

Baumann, L. C., Davidson, K. W., Ebell, M., … B, D.

(2016). Screening for Depression in Adults. JAMA,

315(4), 380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18392.

spms.min-saude.pt. (2017). Retrieved January 31, 2017,

from http://spms.min-saude.pt/product/sclinicocsp/

Stopdepression.pt. (2017). Retrieved January 31, 2017,

from http://stopdepression.pt.

van Ballegooijen, W., Riper, H., Cuijpers, P., van Oppen,

P., & Smit, J. H. (2016). Validation of online

psychometric instruments for common mental health

disorders: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 16, 45.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0735-7.

Warmerdam, L., Riper, H., Klein, M., van den Ven, P.,

Rocha, A., Ricardo Henriques, M., … Cuijpers, P.

(2012). Innovative ICT solutions to improve treatment

outcomes for depression: the ICT4Depression project.

Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 181,

339–343.

Whitfield, G. (2010). Group cognitive–behavioural therapy

for anxiety and depression. Advances in Psychiatric

Treatment, 16(3).

Williams, C., & Martinez, R. (2008). Increasing Access to

CBT: Stepped Care and CBT Self-Help Models in

Practice. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy,

36(6), 675. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246580

8004864.

World Health Organization. (2012). DEPRESSION A

Global Public Health Concern.

Screening and Evaluation Platform for Depression and Suicidality in Primary Healthcare

215