Does the Learning Channel Really Matter?

Insights from Commercial Online ICT-training

Nestori Syynimaa

Faculty of Information Technology, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, Finland

Gerenios Ltd, Tampere, Finland

Sovelto Plc, Helsinki, Finland

Keywords: Learning Channel, Online Training, Online Learning.

Abstract: Evolving ICT has provided new options to participate to training. Online participation has been found to be

cost effective, helping people to deal with the time and cost pressures they are facing on their jobs. Previous

studies conducted in higher education sector indicates that student satisfaction or learning outcomes does not

differ between online and classroom participants. However, little is known what is the situation in commercial

ICT-training. This paper studied course feedbacks from courses having both online and classroom participants

of a commercial ICT-training provider. Results revealed that the learning channel has no effect on satisfaction,

perceived teacher’s substance and teaching skills, or course arrangements. The results also revealed some

areas how the commercial training providers could improve their online training.

1 INTRODUCTION

Information and communication technology (ICT)

has evolved rapidly during the past few decades.

Evolved ICT has provided, for instance, new

communication ways allowing people to be virtually

present in meetings and similar events. In education

sector ICT allows students to participate to the

training using standard affordable consumer

equipment. Typically, all that is needed is a computer

with internet connection and audio support. Modern

laptops have a built-in microphone, speakers, and a

camera.

Interest towards participating to training using

computers with audio and video has increased during

the last few years. For instance, American community

colleges has faced over 32 percent increase in

distance learning in five years between 2008 and

2013 (Lokken & Mullins, 2014). According to

another recent report, the corporate e-learning will

grow 13 percent per year (Ronald Berger, 2014). In

2016, 77 percent of American companies were using

online training tools (Trainingmag, 2016).

Some reasons for the increased interests has been

found. Two of the reasons are work related time and

cost pressures (Ronald Berger, 2014). Due to latest

recession in Europe, the number of workers has

decliced, leaving more jobs for those still working.

Thus the workforce has more pressure to use their

time wisely so they prefer learning channels which

does not require as much travelling. Travelling also

requires money so cost pressures also directs to seek

alternative learning channels.

Due to increased interest towards various kinds of

online training, it is fair to ask: are the new learning

channels as good as the traditional ones? Johnson et

al. (2000) found no differences in learning outcomes

between classroom and online training. Similarly,

Allen et al. (2002) found no differences in student

satisfaction between classroom and online training.

There have been some critique towards studies

conducted on the subject. Many of the studies have

not ruled out other factors which may have effected

the results (Merisotis & Phipps, 1999). Thus, many

studies have failed to demonstrate what is cause and

what is effect. For instance, some studies have

compared two independent samples, one for online

training and one for classroom training.

Aim of this paper is to study whether the used

learning channel (i.e., online vs. classroom) effects

the student satisfaction in commercial ICT-training.

1.1 Online Learning

Online learning is one of the learning methods used

in various training settings. Learning methods can be

Syynimaa, N.

Does the Learning Channel Really Matter? - Insights from Commercial Online ICT-training.

DOI: 10.5220/0006365001490153

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2017) - Volume 1, pages 149-153

ISBN: 978-989-758-239-4

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

149

categorised as four archetypes; traditional learning, e-

learning, participatory learning, and facilitated

learning community (Leppänen & Syynimaa, 2015).

In this paper, we regard online learning as a

technology supported traditional learning, where

teaching occurs in the classroom while at least some

of the students are participating online using audio

and video.

One concept closely involved to learning methods

is Human Learning Interfaces (HLI). HLIs are the set

of “interaction mechanisms that humans expose to the

outside world, and that can be used to control,

stimulate and facilitate their learning processes”

(Koper, 2014, p. 1). Humans learn, for instance, by

interpreting observations they make by utilising their

senses, such as seeing, hearing, and touching.

Teachers can observe and assess whether the learning

has occurred using the same HLIs.

1.2 Challenges in Online Learning

Online learning limits the available senses to seeing

and hearing, so also the number available HLIs are

reduced to two. This affects both learners and

teachers. Learners may not be able learn as effectively

due to limited number of HLIs. For teachers, the

effect is even bigger. Due to limited number of

available HLIs, the teacher is not able to assess

effectively whether the learning has occurred. For

instance, they cannot see learner’s gestures or body

language, which is an important communication

method for humans. Thus, teachers are not able to

adjust their teaching in same way as they can do in

the classroom.

2 METHOD

The data used in this paper is collected from a leading

Finnish commercial ICT-trainer, TrainingCorp.

TrainingCorp provides ICT-training to Finnish

public and private sector organisations, and

individual consumers. Training ranges from end-user

and ICT-specialist training to CxO level management

training. Training is provided in the form of full-day

instructor lead courses (ILT) with typical length

between 1 to 4 days. Since 2015 TrainingCorp has

provided an online participation option, where

learners participate to courses using either Microsoft

Skype for Business (SfB) or Adobe Connect Pro

(ACP). After each course TrainingCorp collects

feedback from all participants.

The data used in this paper was collected from the

feedback database from the years 2015 and 2016. To

increase the validity of the research, only the courses

having both classroom and online participants were

included in sample. In this paper, we call these kind

of course a hybrid course.

The hybrid course has both classroom (CR) and

online (OL) participants. For classroom participants

the training experience is similar to a pure classroom

training. There is a microphone and speakers in the

classroom which allows online participants to hear

the teaching and to speak. On some courses there is

also 360 degree camera which allows online

participants to see the classroom. Tearchers are

sharing their computer screen to online participants,

so they can see the same content that is presented to

classroom participants.

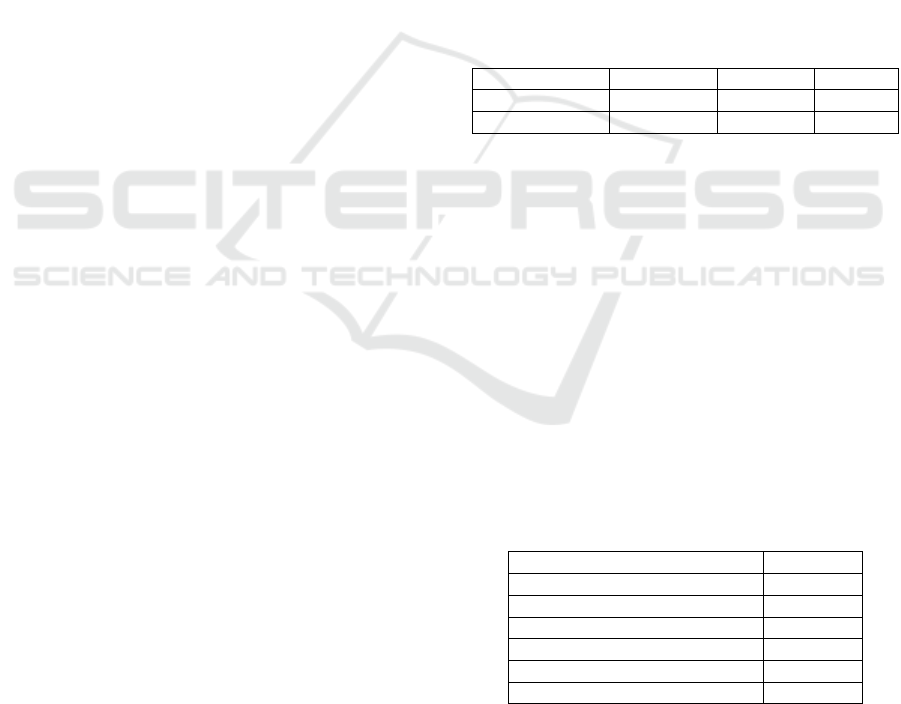

In total, there were 46 hybrid courses. The number

of participants and given feedbacks can be seen in

Table 1. Total number of online participants was 107,

which represents 24% of the total participants.

Table 1: Participants and feedbacks.

Training type Participants Feedback

F

eedb.%

Classroom (CR) 343 (76 %) 218 (75%) 64 %

Online (OL) 107 (24%) 73 (25%) 68 %

Available data variables are listed in Table 2.

There are two nominal scale variables, type and

teacher. The former variable refers to the training type

(classroom or online) and the latter to the course

teacher. The rest of the variables are interval scale

variables containing average values calculated per

course. The scale used in the feedback database is 1-

5 where 5 is the highest value. Average values per

course are used instead of individual answers because

the unit of analysis is the course. The Type variable is

used as a grouping variable and the last four as

dependent variables.

As part of their feedback, respondents can also

give open ended comments about the course. These

comments was also gathered for analysis.

Table 2: Variables used.

Variable Type

Type Nominal

Teacher Nominal

Overall satisfaction (SA) Interval

Teacher’s substance skills (SU) Interval

Teacher’s teaching skills (TE) Interval

Course arrangements (AR) Interval

As the previous studies suggests, there should be no

differencies in the perceived satisfaction between

online and classroom training. However, as the online

training does limit the number of used HLIs, it should

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

150

have effect on the overall satisfaction of the course.

Moreover, the online training helps participants to

ease the time and cost pressures they are facing.

Therefore our first hypothesis is H

1

: learning channel

has effect on the perceived overall satisfaction. The

training channel should be irrelevant regarding to

teacher’s substance and teaching skills. Therefore our

next hypotheses are H

2

: learning channel has no

effect on perceived tearcher’s substance skills and

H

3

: learning channel has no effect on perceived

teacher’s teaching skills. All online training is

exposed to possible technical difficulties and

problems. Therefore our last hypothesis is H

4

:

learning channel has effect on the perceived course

arrangements.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Quantitative Analysis

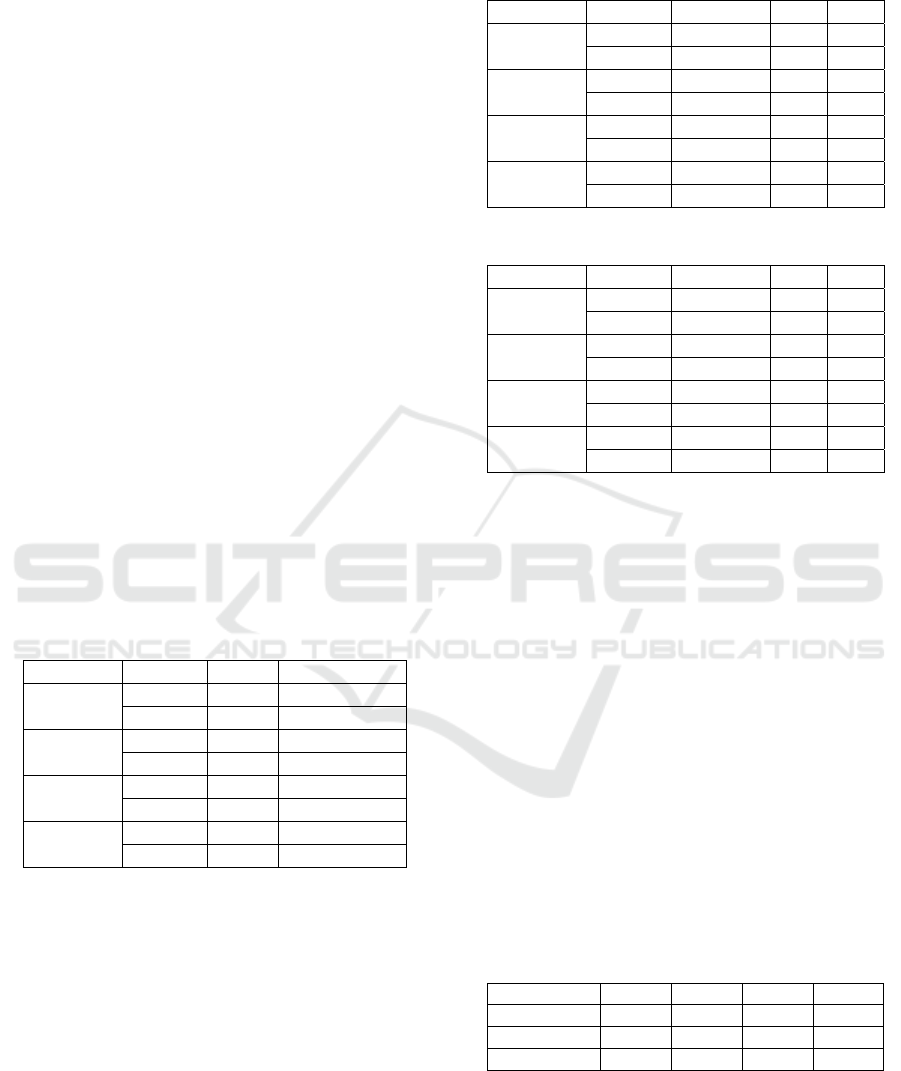

The descriptive statistics presented in Table 3

indicates that the mean values for each variable is

slightly smaller in online training. Also, the standard

deviation is roughly double in online training when

compared to classroom training. Next we will test

whether there is statistically significant difference

between online and classroom training.

Table 3: Descriptive Statistics.

Variable

Type Mean Std. Deviation

SA CR 4.598 .3093

OL 4.472 .6053

SU CR 4.902 .1559

OL 4.884 .3007

TE CR 4.728 .2725

OL 4.649 .4915

AR CR 4.578 .3977

OL 4.207 .8140

We are comparing two different groups of data so first

we must test the normality of the dependent variables.

We used Kolmogorov-Smirnov (Table 4) and

Shapiro-Wilk tests (Table 5). The Kolmogorov-

Smirnov test results indicate that only the overall

satisfaction (SA) in classroom training is normally

distributed (sig. .073 > .050). The Shapiro-Wilk tests

showed no normal distribution at all. Thus, we cannot

compare differencies between classroom and online

training using ANOVA. Therefore, we decided to use

a Kruskal-Wallis H test.

Table 4: Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests with Lilliefors

Significance Correction.

Variable Type Statistics df Sig.

SA CR .125 45 .073

OL .297 43 .000

SU CR .357 45 .000

OL .488 43 .000

TE CR .174 45 .001

OL .344 43 .000

AR CR .156 45 .000

OL .214 43 .000

Table 5: Shapiro-Wilk tests.

Variable Type Statistics df Sig.

SA CR .924 45 .006

OL .777 43 .000

SU CR .676 45 .000

OL .427 43 .000

TE CR .878 45 .000

OL .713 43 .000

AR CR .856 45 .000

OL .834 43 .000

The results of Kruskal-Wallis H tests can be seen in

Table 6. The test showed that there was no

statistically significant difference in the overall

satisfaction (SA) between the classroom and online

training, χ2(2) = .111, p = 0.739. Therefore we must

reject the H

1

hypothesis. The test showed that there

was no statistically significant difference in the

teacher's substance skills (SU) between the classroom

and online training, χ2(2) = 3.549, p = 0.060.

Therefore the H

2

hypothesis is not rejected. The test

showed that there was no statistically significant

difference in the teacher's teaching skills (TE)

between the classroom and online training, χ2(2) =

.233, p = 0.637. Therefore the H

3

hypothesis is not

rejected. The test showed that there was no

statistically significant difference in the course

arrangements (AR) between the classroom and online

training, χ2(2) = 3.714, p = 0.054. Therefore we must

reject also the hypothesis H

4

.

Table 6: Kruskal-Wallis H test (grouping by Type).

Variable SA SU TE AR

Chi-Square .111 3.549 .233 3.714

df 1 1 1 1

Asymp. Sig. .739 .060 .637 .054

As the results suggests, the used teaching channel has

no effect to perceived satisfaction of the training what

so ever.

Does the Learning Channel Really Matter? - Insights from Commercial Online ICT-training

151

3.2 Qualitative Analysis

In total, open ended comments related to online

participation were given for 23 courses. The quotes

presented in this section are translations from the

original feedbacks given in Finnish. The number after

each quote refers to the feedback number.

Most comments were related to technical

difficulties, i.e., audio and video connection. For

instance, one online participant stated that “constant

technical problems ruined the whole and I missed the

most part of the course” (31). Another one stated that

“connection was okay for the first two days..on the

third day there was some problems with the video..the

broadcast were cut at least for 30 minutes before it

was fixed” (8). However, there were also opposite

experiences. For instance, one online participant

stated that “online possibility worked well for the

course” (15). Another participant stated that “this was

my first online participation and everything worked

perfectly!” (30).

Besides the technical matters, there was some

other issues mentioned by online participants. Many

participants felt that they were not able to participate

to discussions same way than the classroom

participants. For instance, one online participant

stated that “as an online participant, I was not given

attention to” (3). Another participants shared similar

experiences, such as, “dialogue and communication

was limited” (35) and “I would have liked to hear

what other participants said or asked..as an online

participant I totally missed this part” (29).

Another issue related to online participation was

the usage of presentation techniques. Some

participants were having problems to follow teaching

when teacher used for instance flip board or pointer.

For instance, one participant suggested that teacher

could have used “an electronic flip board so that

online participants would also see the content” (13).

Another particpant suggested similarly that teacher

could use “some drawing software instead of flip

board” (3).

Only two participants stated that having both

online and classroom participants is not a good idea.

The first participant (classroom) simply stated that

“onsite and online participants at the same time is not

the best option” (25). Another participant (online)

argued that either online or classroom participants are

always “suffering” (37) due to arrangements.

Some participants also shared the reasons why

they participated online. One participant stated that

“it would have been nice to be onsite, but at least this

is cheaper” (2). Another participant emphasised that

“online participation gives a freedom to participate

from wherever you like to” (28). Moreover, one

participant stated that online participation is “a good

alternative for travelling” (30).

4 DISCUSSION

Our premise for the research was that the learning

channel has effect on participants’ satisfaction of the

course. Online training limits the number of HLIs and

therefore it was anticipated that there would be some

effect on satisfaction. However, the data analysis

provided no support for this. Thus, our finding is in

line with previous studies. Allen et al. (2002) found

no differences on satisfaction between online and

classroom students, and Sun et al. (2008) did not

found any technological factor having effect on

satisfaction. As the results suggests, we may draw a

conclusion that the used learning channel does not

matter. It has no significant effect on overall

satisfaction, perceived teacher substance or teaching

skills, or course arrangements.

Open ended feedbacks indicated some challenges

in online participation. Biggest issues seems to be

technical problems with video and audio. However,

these issues were not faced by the whole class at the

same time but by individual students. This finding is

also in line with previous findings; technical

problems are frustrating students (Sun et al., 2008).

Some of the online participants felt that they did not

receive enough attention from the teacher, and that

they were “outsiders”. One reason for this might be

teacher’s repertoire of presentation techniques. Some

online participants reported that they could not follow

all teaching when teacher used flip boards or pointers.

Knipe and Lee (2002) have noticed similar

pedagogical challenges; online participants does not

receive as much information and explanations from

the teacher as the classroom participants do.

As suggested by Ronald Berger (2014),

participants indicated that online participation saves

money in terms of travelling. It also gives the choice

of freedom regarding from where to participate.

4.1 Limitations

In this research, we studied whether the used learning

channel have effect on student satisfaction. As such,

the results do not reveal any effects on actual learning

outcomes.

4.2 Contributions to Practice

As the findings revealed, the learning channel had no

CSEDU 2017 - 9th International Conference on Computer Supported Education

152

effect on participants’ satisfaction. Therefore, we

would like to encourage training providers to consider

offering more online participation options. At the

same time, however, there are some issues which

should be noticed and dealt with. First, the reliable

internet connection and video conferencing

equipment should be used and tested beforehand.

Teachers should also familiarise themselves with the

used technology. Second, teachers should give more

attention to online participants. This includes using

appropriate teaching aids, such as electronic flip

boards, and effective communication techniques,

such as frequently asking questions.

4.3 Contributions to Science

The study confirms findings of previous studies

conducted on higher education sector. Our findings

show that commercial ICT-training does not differ

from higher education in this matter.

4.4 Directions for Future Research

The findings pointed out some issues with used

teaching aids. The TrainingCorp used two different

technical solutions to provide online training. The

feedback data did not include information on which

tool was used on each course. Thus, the first

interesting area for future research would be to study

whether the used solution have effect on satisfaction.

Second interesting area would be to study which kind

of teaching aids for classroom and online training

does the solutions provide. Third interesting area

would be to study how teachers feel teaching

classroom and online students at the same time.

Finally, as indicated earlier, one should study whether

the learning channel effects the actual learning

outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to express his gratitude to

TrainingCorp for providing access to the feedback

data used in this paper.

REFERENCES

Allen, M., Bourhis, J., Burrell, N., & Mabry, E. (2002).

Comparing Student Satisfaction With Distance

Education to Traditional Classrooms in Higher

Education: A Meta-Analysis. American Journal of

Distance Education, 16(2), 83-97. doi:10.1207/

S15389286AJDE1602_3.

Johnson, S. D., Aragon, S. R., Shaik, N., & Palma-Rivas,

N. (2000). Comparative Analysis of Learner

Satisfaction and Learning Outcomes in Online and

Face-to-Face Learning Environments. Journal of

Interactive Learning Research, 11(1), 29-49.

Knipe, D., & Lee, M. (2002). The quality of teaching and

learning via videoconferencing. British Journal of

Educational Technology, 33(3), 301-311. doi:10.1111/

1467-8535.00265.

Koper, R. (2014). Conditions for effective smart learning

environments. Smart Learning Environments, 1(5), 1-

17.

Leppänen, S., M., & Syynimaa, N. (2015). From Learning

1.0 to Learning 2.0: Key Concepts and Enablers. Paper

presented at the 7th International Conference on

Computer Supported Education (CSEDU 2015),

Lisbon, Portugal.

Lokken, F., & Mullins, C. (2014). ITC 2013 Distance

Education Survey Results. Retrieved from Washington:

Merisotis, J. P., & Phipps, R. A. (1999). What's the

Difference?: Outcomes of Distance vs. Traditional

Classroom-Based Learning. Change: The Magazine of

Higher Learning, 31(3), 12-17. doi:10.1080/

00091389909602685.

Ronald Berger. (2014). Corporate Learning Goes Digital.

How companies can benefit from online education.

Think Act, (pp. 20). Retrieved from https://www.

rolandberger.com/publications/publication_pdf/roland

_berger_tab_corporate_learning_e_20140602.pdf.

Sun, P.-C., Tsai, R. J., Finger, G., Chen, Y.-Y., & Yeh, D.

(2008). What drives a successful e-Learning? An

empirical investigation of the critical factors

influencing learner satisfaction. Computers &

Education, 50(4), 1183-1202.

Trainingmag. (2016). Training Industry Report 2016

Retrieved from https://trainingmag.com/sites/default/

files/images/Training_Industry_Report_2016.pdf.

Does the Learning Channel Really Matter? - Insights from Commercial Online ICT-training

153