Healthcare Recommendations from the Personalised ICT Supported

Service for Independent Living and Active Ageing

(PERSSILAA) Study

Rónán O’Caoimh

1,2, 3

, D. William Molloy

1,2

, Carol Fitzgerald

1

, Lex Van Velsen

4,5

, Miriam Cabrita

4,5

,

Mohammad Hossein Nassabi

5

, Frederiek de Vette

5

, Marit Dekker-van Weering

4

,

Stephanie Jansen-Kosterink

4

, Wander Kenter

4

, Sanne Frazer

4

, Amélia P. Rauter

6

, Antónia Turkman

6

,

Marília Antunes

6

, Feridun Turkman

6

, Marta S. Silva

6

, Alice Martins

6

, Helena S. Costa

7,8

,

Tânia Gonçalves Albuquerque

7,8

, António Ferreira

6

, Mario Scherillo

9

, Vincenzo De Luca

10

,

Maddalena Illario

10

,

Alejandro García-Rudolph

11

, Rocío Sanchez-Carrion

11

,

Javier Solana Sánchez

12,13

, Enrique J. Gomez Aguilera

12,13

, Hermie Hermens

4,5

and Miriam Vollenbroek-Hutten

4,5

1

Centre for Gerontology and Rehabilitation, University College Cork, St Finbarrs Hospital, Cork City, Ireland

2

COLLaboration on AGEing, University College Cork, Cork City, Ireland

3

Health Research Board, Clinical Research Facility Galway, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland

4

Roessingh Research and Development, Enschede, Netherlands

5

University of Twente, Enschede, Netherlands

6

Fundação da Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

7

Instituto Nacional de Saúde Doutor Ricardo Jorge, IP, Lisboa, Portugal

8

REQUIMTE/LAQV, Faculdade de Farmácia da Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal

9

Nexera Centro Direzionale Isola, Napoli, Italy

10

Federico II University Hospital, Napoli, Italy

11

Institut Guttmann, Institut Universitari de Neurorehabilitació adscrit a la UAB, Badalona, Barcelona, Spain

12

Biomedical Engineering and Telemedicine Center. ETSI Telecomunicacion. Centre for Biomedical Technology,

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

13

Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red, Biomateriales y Nanomedicina (CIBER-BBN), Zaragoza, Spain

Keywords: Frailty, Pre-frailty, Information and Communication Technology, Clinical, Healthcare Recommendations,

Guidelines.

Abstract: In the face of demographic ageing European healthcare providers and policy makers are recognising an

increasing prevalence of frail, community-dwelling older adults, prone to adverse healthcare outcomes. Pre-

frailty, before onset of functional decline, is suggested to be reversible but interventions targeting this risk

syndrome are limited. No consensus on the definition, diagnosis or management of pre-frailty exists. The

PERsonalised ICT Supported Service for Independent Living and Active Ageing (PERSSILAA) project

(2013-2016 under Framework Programme 7, grant #610359) developed a comprehensive Information and

Communication Technologies (ICT) supported platform to screen, assess, manage and monitor pre-frail

community-dwelling older adults in order to address pre-frailty and promote active and healthy ageing.

PERSSILAA, a multi-domain ICT service, targets three pre-frailty: nutrition, cognition and physical

function. The project produced 42 recommendations across clinical (screening, monitoring and managing of

pre-frail older adults) technical (ICT-based innovations) and societal (health literacy in older adults,

guidance to healthcare professional, patients, caregivers and policy makers) areas. This paper describes the

25 healthcare related recommendations of PERSSILAA, exploring how they could be used in the

development of future European guidelines on the screening and prevention of frailty.

O’Caoimh, R., Molloy, D., Fitzgerald, C., Velsen, L., Cabrita, M., Nassabi, M., Vette, F., Weering, M., Jansen-Kosterink, S., Kenter, W., Frazer, S., Rauter, A., Turkman, A., Antunes, M.,

Turkman, F., Silva, M., Martins, A., Costa, H., Albuquerque, T., Ferreira, A., Scherillo, M., Luca, V., Illario, M., García-Rudolph, A., Sanchez-Carrion, R., Sánchez, J., Aguilera, E., Hermens,

H. and Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.

Healthcare Recommendations from the Personalised ICT Supported Service for Independent Living and Active Ageing (PERSSILAA) Study.

DOI: 10.5220/0006331800910103

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2017), pages 91-103

ISBN: 978-989-758-251-6

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

91

1 BACKGROUND

With demographic ageing the number of older

Europeans, aged over 65 years, has increased

(Rechel, 2013), resulting in a higher prevalence of

frailty (Collard, 2012). Despite the lack of an

accepted definition most experts consider frailty to

be an age-associated loss of physiological reserve,

characterised by an increased vulnerability to

adverse healthcare outcomes (Sternberg, 2011),

(Borges, 2011), (Rodríguez-Mañas, 2013), (Morley,

2013).

Pre-frailty, is a prodromal ‘risk’ state before the

onset of frailty. However, no definition of pre-frailty

is yet available. Instead, a cut-off score on a frailty

screen or frailty assessment scale defines it as an

intermediate level before the development of

functional decline. The proportion of frail,

community dwelling older adults is variable

depending on the sample and setting surveyed but

can be as high as half (Collard, 2012). A greater

percentage, up to 60% of those aged over 65, can be

classified as pre-frail (Santos-Eggimann, 2009),

although again this depends on the approach used to

categorise pre-frailty (Roe, 2016).

While the development of frailty is often

considered permanent, some patients may convert

from frail to pre-frail and even become robust again

(Gill, 2006). Nevertheless, once established, frailty

is challenging or near impossible to reverse (Lang,

2009) with less than 1% of patients transitioning

back over five years of follow-up (Gill, 2006).

Given that the onset of frailty is associated with an

increased incidence of chronic medical conditions

(Gray, 2013), (Sergi, 2015), hospitalisation

(O’Caoimh, 2012a), (O’Caoimh, 2014a),

(O’Caoimh, 2015a), hospital readmission (Kahlon,

2015), healthcare costs (Robinson, 2011),

institutionalisation (Sternberg, 2013), and death

(Song, 2010), there is a need to promote active and

healthy ageing and instigate measures to prevent

frailty (Morley, 2013), (Bousquet, 2014),

(O’Caoimh, 2015b), (Fairhill, 2015), (Michel, 2016).

From a practical perspective targeting pre-frailty is a

reasonable approach. Specifically, the use of multi-

factorial interventions to screen, monitor and

manage prodromal states related to pre-frailty such

as subjective or mild cognitive impairment

(Fiatarone, 2014), (Ngandu, 2015), (O’Caoimh,

2015c), and reduced physical activity (Bherer,

2013), (Pahor, 2014) may be the best approach.

Likewise combinations of proactive, coordinated

and targeted interventions, delivered in the

community, can reduce adverse healthcare outcomes

among older adults (Beswick, 2008).

To date, few clinical trials have used frailty as an

outcome measure (Lee, 2012), examined whether

frailty can be prevented or studied whether directing

interventions towards pre-frail community-dwelling

older adults delays onset of frailty and functional

decline. Specifically, no study has examined the use

of a multi-domain, information and communications

technology (ICT) platform. Although several

national and international Geriatric Medicine

societies have provided best practice

recommendations for addressing frailty (Morley,

2013), (Turner, 2014), given the paucity of studies,

no guidelines exist for the management of pre-

frailty.

2 OVERVIEW OF THE

PERSSILAA PROJECT

The PERsonalised ICT Supported Services for

Independent Living and Active Ageing

(PERSSILAA) project is a small or medium-scale

focused research project, funded under the European

Commissions’ Framework Programme 7 (FP7)

(2013-2016, grant #610359). It consists of a

consortium of eight partners from five European

Union countries from across the social, medical and

technological sciences as well as industry, academia

and end-user organisations. The primary objective of

PERSSILAA was to develop an ICT-based platform

to identify and manage community dwelling older

adults at risk of functional decline and frailty. This

multimodal service model focuses on important pre-

frailty domains, namely: nutrition, cognition and

physical function. It is supported by an interoperable

ICT service infrastructure, using an intelligent

decision support system and gamification strategies

to encourage end-users to engage with the platform.

PERSSILAA was designed specifically for

community-dwelling older adults (aged >65 years)

who as part of the project were (1) screened using

continuous trained rater and or self-assessment

strategies to identify and stratify their “frailty level”,

(2) triaged to the appropriate ICT based solution to

meet their needs (targeting one, more or all three

frailty domains), (3) monitored (unobtrusively) and

(4) managed with ICT supported services through

local community services.

In summary, the intervention consisted of both

face-to-face and remote ICT components. Suitable

participants identified in one of the two evaluation

sites, Enschede, the Netherlands (older adults aged

65-75 recruited through primary care, selected by

their family doctor) and Campania, Italy (older

adults >65 recruited through local church

communities), were screened for frailty using a two-

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

92

step screening process. Once identified,

PERSSILAA services were used first to deliver

specific trainings modules for health and ICT

literacy and where appropriate, based on the

screening and triage component, to physical training,

cognitive training (Guttmann

NeuroPersonalTrainer®) and nutritional advice

(NUTRIAGEING

TM

website). The PERSSILAA

services are accessible and offered online via

personal or tablet computers so older adults can use

them independently. In addition to a standard

version there is also a gamified version which wile

designed to be fun and interactive, encourages

participation and compliance with the intervention,

something referred to as ‘serious gaming’. For

example in one version subjects are challenged to

build a boat to escape from a virtual island but can

only gather the pieces required by using the trainings

modules. Gamification encourages older people to

use telemedicine (de Vette, 2015) with a recent

systematic review showing that it generates more

engaging assessment strategies for cognition (brain

training), (Lumsden, 2016).

The PERSSILAA study investigated the extent

to which this ICT platform was first acceptable to

older adults, then efficacious and ultimately

effective in a real world setting, in preventing pre-

frail older adults from becoming frail. As this was an

evaluation rather than a validation study, the priority

was on demonstrating acceptability and proof of

concept. PERSSILAA services were studied in two

different communities of older adults in Italy and the

Netherlands. Two different evaluation studies were

performed. In Campania, a prospective cohort study

was conducted to examine the uptake, acceptability

and usability of the platform among older Italians. In

Enschede, a multiple cohort randomised controlled

trial (mcRCT) design was used recruiting 82

participants from several Dutch sites across the

region (46 of whom received the intervention). Cost

effectiveness was assessed with the Monitoring and

Assessment Framework for the European Innovation

Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing tool

(Boehler, 2015) developed under the European

Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy

Ageing (EIP on AHA). The PERSSILAA study was

funded for three years with the evaluation

component conducted over the last two years.

Subjects were consented and assessed at baseline,

scheduled intervals and the end-point. More details

of the project including a full list of publications are

available at www.perssilaa.eu.

3 RECOMMENDATIONS FROM

THE PERSSILAA PROJECT

Given the interdisciplinary nature of the

PERSSILAA project, the results derived from it are

multi-dimensional and can be broadly categorised

into three thematic areas: Healthcare related

recommendations, ICT-related recommendations

and Organisational (institutional) related

recommendations. This review summarises the

healthcare findings relating to the project.

To compile these, partners were grouped

according to their relevant specialty to develop

recommendations based on the work completed in

the preparation of the project including an expert

external review and the results emerging from the

project. Each component was evaluated separately

and once complete all partners provided feedback

and the recommendations were grouped as described

above.

There are several recommendations within each

theme. The results presented in this paper describe

the clinically relevant outcomes of the study and

how these could be used to contribute to the

development of European guidelines for the

screening of and prevention of frailty in older adults.

3.1 Definition of Pre-frailty

Although pre-frailty may be characterised as a

prodromal state before onset of frailty and

subsequent functional decline, no clear definition of

pre-frailty exists. Instead it is most often

characterised only as a transitional stage between

robust and frail states, measured by several short

frailty screens and defined by a cut-off score above a

robust level but below that for frailty. It is

acknowledged that there is a need to identify this

prodrome so that measures to effectively target

frailty can be developed (Fairhall, 2015). In order to

select a sample, the PERSSILAA investigators

produced a definition of pre-frailty following a

detailed state of the art literature review. After

reviewing several possible definitions, the

investigators developed a multi-domain definition

targeting the key frailty domains (nutrition,

cognition and physical function) of the project. As

several of the partners were involved in the EIP on

AHA A3 Action Group on frailty prevention (Illario

2016), the definition of pre-frailty was based upon

the A3 groups’ definition of frailty. This describes

pre-frail older adults those at increased risk for

future poor clinical outcomes, such as the

development of disability, dementia, falls,

hospitalisation, institutionalisation or increased

mortality as evidenced by the presence of one or

Healthcare Recommendations from the Personalised ICT Supported Service for Independent Living and Active Ageing (PERSSILAA)

Study

93

more prodromal frailty states (e.g. mild cognitive

impairment, sarcopenia, physical and functional

impairment, dysthymia and social isolation).

Recommendation: The EIP on AHA definition of

frailty could be adapted to define pre-frailty.

Recommendation: The EIP on AHA action group

A3 should take the lead in developing a definition of

pre-frailty, which could support and stimulate

debate on a consensus definition of this important

condition and public health priority.

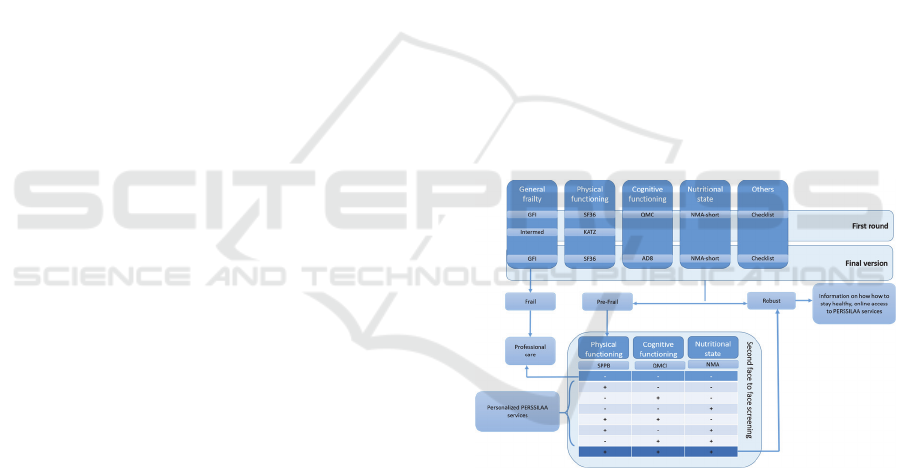

3.2 Screening for Pre-frailty

Multiple short frailty screening instruments are

currently available (de Vries, 2011), though no

single instrument is recommended (Morley, 2013).

Further, only a few scales are able to discriminate

the pre-frail. PERSSILAA was predicated on a two-

step screening and assessment approach in an

attempt to correctly categorise subjects as frail.

Staged screening followed by more comprehensive

assessment is recommended given the high

prevalence of pre-frailty in community samples and

the resources involved to screen in this setting (van

Kempen, 2015). Instruments were selected following

a literature review. This two-stage selection involved

(1) the screening of people aged 65 years and older

by trained volunteers/self-screening either by email

or postal questionnaire to exclude robust subjects

and those with established frailty and (2) a second-

level face-to-face assessment by multidisciplinary

staff of those classified as pre-frail in order to

confirm if they were pre-frail. Each of the three

domains included in PERSSILAA were screened

using this approach i.e. physical, nutritional and

cognitive pre-frailty. The specific instruments used

at each stage of the process are presented in Figure

1. During the first iteration (the first round) the

scales were rationalised resulting in a more

streamlined version (final version).

In summary, in the first step subjects were

divided into robust, pre-frail and frail using a

‘global’ frailty scale and individual measures of

nutrition, cognition and physical function. Two

‘global’ instruments were initially selected (1) the

Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI), a 15-point yes-no

questionnaire exploring physical, cognitive, social

and psychological components of frailty taking a

cut-off of ≥4/15 for moderate-severe frailty

(Steverink, 2001) and (2) the INTERMED (self-

rated version) screen, a reliable, self-administered

20-question survey covering biological,

psychological, social factors and the extent of recent

healthcare usage (Peters, 2013). As the INTERMED

did not provide sufficient additional information,

only the GFI was used in the final version, as it was

shorter, validated in the languages of the project and

easier to use. Participants were further screened

using instruments specific to the selected pre-frailty

domains using appropriate cut-off scores. The final

instruments selected were the Mini-Nutritional

Assessment (MNA) short form for nutrition, the 8-

item Alzheimer’s disease 8 questionnaire (AD8) for

cognitive impairment (Galvin, 2005) and the Short-

form 36 questionnaire (SF-36) for physical

impairment. The KATZ activities of daily living

(ADL) scale and Quick Memory Check (QMC) were

initially trialled in the ‘first round’ (see Figure 1) but

were felt to be impractical for self-screening.

In the second step (face-to-face assessment),

older adults were assessed to confirm if they were

pre-frail. Nutritional deficits were identified using

the remainder of the MNA (G-R), mild cognitive

impairment was identified with the brief Quick Mild

Cognitive Impairment (Qmci) cognitive screen

(O’Caoimh, 2012), (O’Caoimh, 2013), (O’Caoimh,

2014a), (Bunt, 2015), (O’Caoimh, 2016), using age

and education adjusted cut-offs, (O’Caoimh, 2017),

and a short physical performance battery (using the

Timed Up-and-Go Test, the Two-Minute Step Test,

the Chair-Stand Test, and the Chair-Sit-and-Reach

Test) were used for physical function.

Figure 1: Two-step screening protocol for the

PERSSILAA project showing the first and final version of

the first screening step.

The results showed that the two-step

PERSSILAA screening-service, when combined

with additional demographic data seems a good

method to quickly and accurately classify

community-dwelling older adults into robust, pre-

frail and frail. In all, 4071 participants were pre-

screened (step one). The majority of these

participants were classified as robust (60%) at first

step screening. A further 916 (23%) were

characterised as having a high probability of being

pre-frail and suitable for further assessment (step

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

94

two). The second face-to-face screening confirmed

that of these 90% were pre-frail.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis

showed that the marker of nutrition, the MNA, was

the most accurate predictor of pre-frailty (area under

the curve of 0.80). Logistic regression was used to

confirm whether those screening positive were truly

pre-frail and showed that the first-step screening

process had an overall good to excellent accuracy

(area under the curve of 0.87 with a sensitivity of

77% and specificity of 84%). Further analysis of the

second level assessment showed a good agreement

among the classifications of pre-frail and robust

individuals. Thus, the results suggest that the two-

step screening approach developed as part of the

PERSILLAA is able to correctly categorise pre-frail

community-dwelling older adults.

Recommendation: Pre-frailty should be

considered a multi-domain, multi-factorial

syndrome.

Recommendation: Several, different pre-frailty

sub-domains should be addressed when screening

for and assessing pre-frailty among older adults and

should include cognitive, physical, nutritional and

social domains.

Recommendation: More research is required in

this area and future studies should capture multiple

pre-frailty domains along with global measures of

frailty.

Recommendation: A two-step screening

approach is an acceptable and accurate means to

identify pre-frailty in a community setting, though

more research to confirm this approach is required.

3.3 ICT Training Modules to Manage

Pre-frailty

Three training modules were developed as part of

PERSSILAA, one for each of the three domains

targeted by the project: nutrition, cognition and

physical function. This section outlines how each

module was developed, the results of their

implementation, the conclusions drawn by the

PERSSILAA researchers and the recommendations

made. This section also puts a special emphasis on

health literacy, an important and often overlooked

element in the care of older adults. It also includes a

preliminary analysis of the effects of the training

platform on quality of life.

3.3.1 Nutrition Training Module

Nutrition plays an important role across the life span

but especially for older adults. Among community-

dwelling older people between 10-35% are

undernourished i.e. at risk of malnutrition (Schilp,

2012) or malnourished (Shakersain, 2016). The

prevalence can reach 45% in hospital (O’Shea,

2016) and between 30%-65% for those in

institutionalised care (Pauly, 2007) though figures

vary by setting and sample characteristics. The cause

is often inappropriate food consumption (van

Staveren, 2011), manifest by a gap between actual

nutrient consumption and recommended dietary

intakes. Education on healthy eating and nutrition is

important to provide adequate and reliable

information to consumers to promote healthy diets.

The NUTRIAGEING website

(http://nutriageing.fc.ul.pt/) is an easy-to-use, “app-

like” interface with minimal menus or other clutter

designed to promote translate scientific knowledge

into usable person-centred nutritional advice for the

general public. It’s three areas are: (1) Healthy

eating, (2) Recipes and videos, and (3) Vegetable

gardens. The “Recipes and videos” subsection

includes 15 videos of recipes developed by the

famous Portuguese Chef Hélio Loureiro. The

functionality of the website was tested in two day

care centres in Portugal with 45 older adults and

their caregivers. In free text feedback sessions,

participants rated the site as excellent but noted that

ICT bridging science and public knowledge such as

the NUTRIAGEING

TM

website should be: (1) easy

to use, (2) evidence based and evaluated by experts

and (3) have their contents presented in an appealing

and enjoyable format to encourage access and

learning.

Recommendation: Nutritional education,

required to promote healthier eating habits among

the general population and in particular pre-frail

older adults, can be delivered successfully online.

Recommendation: Educating caregivers on the

benefits of nutrition using ICT-supported platforms

such as the NUTRIAGEING

TM

website is important

and may benefit older adults directly – more

research is required to confirm this.

Recommendation: Educating cooks and

professionals involved in food preparation on the

benefits of healthy foods and nutrition using ICT

supported platforms such as the NUTRIAGEING

TM

website is important and may benefit older adults

directly – again research is required to confirm this.

Healthcare Recommendations from the Personalised ICT Supported Service for Independent Living and Active Ageing (PERSSILAA)

Study

95

Recommendation: ICT platforms, if user friendly

and intuitively designed, can provide the general

population but also older persons and healthcare

professionals with reliable information and easy-to-

use tools, which may increase their knowledge of

nutrition and healthy eating.

3.3.2 Cognition Training Module

Demographic ageing is associated with an increased

prevalence of cognitive impairment including mild

cognitive impairment (Plassman, 2008) and

dementia (Prince, 2013). Recent data suggest that

the incidence (Satizabal, 2016) and prevalence

(Matthews, 2013), (Langa, 2016) of dementia may

be falling in developed countries, possibly reflecting

improved education, socioeconomic factors and

cardiovascular brain health, all of which may

contribute to cognitive reserve (Norton, 2014).

Further, studies trialling multi-domain interventions

targeting at risk populations show that cognitive

stimulation when deployed with other lifestyle

measures and cardiovascular risk-factor assessment

and treatment may reduce progression to dementia

(Ngandu, 2015), Cognitive training, often called

‘brain training’ typically involves guided practice on

a set of standardised tasks designed to reflect

particular cognitive functions.

In PERSSILAA the mean AD8 score for the

total sample of 4,071 participants screened at step

one was 0.66±1.22 compared to 1.03±1.28 for pre-

frail older adults. A score of two or greater is

suggestive of cognitive impairment (Galvin, 2005),

though specificity is low at this cut-off (Larner,

2015). The mean Qmci score of pre-frail participants

at the second step was 64.5/100 ±11.32, within the

accepted range of cut-off scores for separating mild

cognitive impairment from normal cognition:

between 64 and 70/100 (O’Caoimh, 2017).

Over the course of the evaluation, pre-frail older

adults were asked to complete the cognitive training

modules over 12 weeks, 3 times per week with each

session designed to last one hour. The cognitive

training tasks were selected from the Guttmann

NeuroPersonalTrainer® and incorporated into the

platform in two blocks. The first group (Block 1)

were assessment-oriented tasks and the second

group (Block 2) training-oriented tasks. Block 1 was

composed of 10 different tasks, Block 2 25 tasks.

Both groups of tasks cover the main cognitive

functions involved in ADL. The therapeutic range

was set between 65%-85% and difficulty levels were

adjusted up/down if the number of correct

answers/responses were less or exceeded this.

Cognitive training was trialled in both evaluation

sites. In Enschede (Netherlands) 18 older adults

participated individually completing a total of 893

tasks during 107 sessions. In Campania (Italy) 53

participated in 15 collective (group) sessions: a total

number of 223 individual log in’s. Usability testing

performed in both regions showed satisfactory

results. In the Netherlands eight participants were

tested, ten in Italy. The mean score across both sites

on the system usability scale (SUS), a subjective 10-

item Likert scale measuring usability (Brooke,

1996), was 64/100 suggesting that the cognitive

training was usable. Based upon the results the

following recommendations were made:

Recommendation: Cognitive training tasks for

use with pre-frail older adults should be easy to

understand and use. Important information should

be provided in a large, conspicuous, non-crowded

format in the person’s central visual field.

Recommendation: The visual display on

cognitive training devices for pre-frail older adults

should be simple; avoiding distracting visual stimuli

(such as elaborate backgrounds and flashing or

flickering lights) unless they are used judiciously to

signal a specific required action or function.

Recommendation: Clear instructions should be

provided to pre-frail older adults before each

cognitive training task, particularly where

additional effort is required on behalf of the end

user (e.g. sustained attention tasks).

Recommendation: Immediate feedback should

always be provided to pre-frail older adults after

completing individual cognitive training activities.

Aggregated information should also be provided to

show trends or evolution in performance over time.

Recommendation: The difficulty of cognitive

training tasks for pre-frail older adults should be

tailored to each individual’s level based upon

normative data for these tasks.

Recommendation: Cognitive training modules

for pre-frail older people should be adapted to

mobile/smart technologies and devices. Engagement

with training should be encouraged with techniques

such as gamification or through the use of group

work (either remotely or at centralised locations).

Recommendation: Fields that represent pre-frail

older adults’ interests or hobbies should be used

throughout cognitive tasks (in the form of images,

texts, words etc.) to personalise the experience for

older adults

.

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

96

3.3.3 Physical Training Module

Frailty and pre-frailty are associated with

sarcopenia, osteopenia and osteoporosis that

contribute to adverse outcomes such as falls and hip

fractures (Liu, 2015). Regular physical activity,

particularly resistance exercises, may prevent onset

of frailty (Liu, 2011). Data also suggests that

exercise interventions can improve ADL function

among frail older adults and delay progression of

functional impairment or disability (Giné-Garriga,

2014). The Otago Exercise Programme (OEP), an

established, validated, cost-effective home-based

tailored falls prevention programme (Robertson,

2001), reduces the risk of falls and mortality among

community-dwelling older adults (Thomas, 2010),

though it is unknown whether it can be used

remotely by pre-frail older patients.

A technology-supported self-management,

physical training module platform, based on the

OEP, was developed for use on the PERSSILAA

platform. This was structure around an existing

platform called the Condition Coach (CoCo) for

patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary

Disease (Tabak, 2014), containing advice and

instructional videos, which was reconditioned for

use with pre-frail older through a iterative design

approach until a final version was released. A more

extensive description of the development of the

physical module is presented elsewhere

(Vollenbroek-Hutten, 2015).

Participants using the physical training module

were requested to train online three times a week for

three months. Few participants dropped out mainly

due to their own health problems, which prevented

them from exercising. Initial technical problems e.g.

with browsers were resolved by setting up a

helpdesk. Of the participants finishing the complete

protocol (i.e. 12 weeks of training), the majority

continued using the service for up to one year. Most

who used the module were very satisfied and

evaluated the module as excellent, scoring a mean of

84/100 on the SUS. In the mcRCT the mean values

of the Chair Stand Test and Two minutes step test

increased for those using the physical training model

compared to controls.

Recommendation: Strategies to motivate pre-

frail older adults to begin and to continue using

physical training modules on ICT supported

platforms should be included as part of the

implementation process.

Recommendation: A ‘home’ online physical

training module provided on an ICT supported

platform is feasible for pre-frail older adults, though

professional support seems useful and should be

provided as back up.

Recommendation: The provision of physical

training modules on ICT supported platforms to pre-

frail older adults, at risk of frailty or functional

decline may enable them to improve their physical

fitness.

3.3.4 Health and ICT literacy

As older adults represent the fastest growing section

of our population and the biggest users of healthcare,

insufficient attention is paid to their understanding

of health literature. It is known that simple measures

can rapidly improve older person’s understanding

(Manafo, 2012). This also applies to eHealth literacy

skills (Norman, 2006). In PERSSILAA health and

ICT literacy programmes were developed in Italy.

This worked on a train the trainer model with

healthcare experts teaching local volunteers. In all

2,560 older adults attended classes, with a mean

attendance of 13.5 older adults per lesson. Feedback

was excellent and older adults reported in

subsequent surveys that they required this education

in order to interact with the training and monitoring

modules (see Section 3.5)

3.4 Effects on Quality of Life

Frailty has a negative impact upon quality of life

(Strawbridge, 1998). At the beginning of the project

a survey conducted with participants suggested high

levels of loneliness and depressive symptoms. In all,

73% reported feeling empty and 74% mow mood or

depressive symptoms. Thus, in addition to the pre-

frailty screening and assessment scales, the

European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions

questionnaire or EQ-5D (Euroqol), scored from 0

(worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best

imaginable health state), was used to measure the

effects of the PERSSILAA training modules on

quality of life. This was also included to facilitate an

economic analysis of the cost effectiveness of the

project. The EQ-5D was measured at baseline and

end-point for those participating in the mcRCT. The

final mean score increased compared with the initial

assessment by a mean of 10 points suggesting that

those using PERSSILAA reported a higher quality

of life after using the platform. The Short-Form 12

(SF-12), which includes physical and mental

domains taken from the SF-36 was used to measure

perceived health. Higher scores were found on the

Mental Component Survey of the SF-12 for those

using PERSSILAA training services compared to

the control group, suggesting that better mental

health is associated with the used of the platform.

Healthcare Recommendations from the Personalised ICT Supported Service for Independent Living and Active Ageing (PERSSILAA)

Study

97

Recommendation: Engaging in online mulit-

domain training modules to manage pre-frailty may

improve the perceived quality of life of older adults.

3.5 Monitoring for the Development of

Frailty – Frailty Transitions

Studies of frailty trajectories show that few older

adults can transition from frail to pre-frail or robust

(Gill, 2006). These have been limited by the type of

data available, which relies on face-to-face

assessment. While technology is suggested to allow

for unobtrusive monitoring, it may distract end-users

and lead to ‘attention theft’, necessitating a more

non-invasive approach in the home environment,

particularly when daily activities are being measured

(Bitterman, 2011). Further, while useful with

younger adults, it is unclear if such models are

applicable to community-dwelling older adults.

While older adults do engage with ICT, its uptake is

low (Selwyn, 2003). Older people perceive ICT to

be of little utility and frequently rank their

technology skills as low (Scanlon, 2015). Further, it

is challenging to combine all the information

collected in a meaningful way in order to obtain an

overview of the everyday functioning of pre-frail

older adults.

Different approaches to monitoring were used in

PERSSILAA depending on the pre-frailty domain

assessed. To facilitate monitoring software was

provided on the portal and on mobile and home

sensing devises. All data were collected

automatically and uploaded into the PERSSILAA

database for analysis. Transitions between different

frailty states (robust, pre-frail and frail) were

examined using the GFI data at baseline and end-

point. To monitor nutrition two questionnaires were

placed on the PERSSILAA portal to evaluate eating

habits: the 24-hour dietary recall and an additional

‘general’ questionnaire developed by the

PERSSILAA investigators. To supplement this, a

‘smart scale’ (weighing scale connected wirelessly

to a computer application) was chosen to monitor

weight on a daily basis. For cognition a shorter

version of the full Guttmann

NeuroPersonalTrainer® was developed to enable

monitoring of cognitive function over time in short

sessions of less than 15 minutes comparing each

score with baseline and the previous results. For

physical function a step counter was chosen to

monitor daily physical activity and obtain an

overview of physical functioning, all collected by

means of a smartphone application. Wellbeing was

also measured daily using a smartphone application

recorded. The acceptability of the monitoring

module was evaluated through semi-structured

interviews and by measuring how frequently the

technology was used over one month.

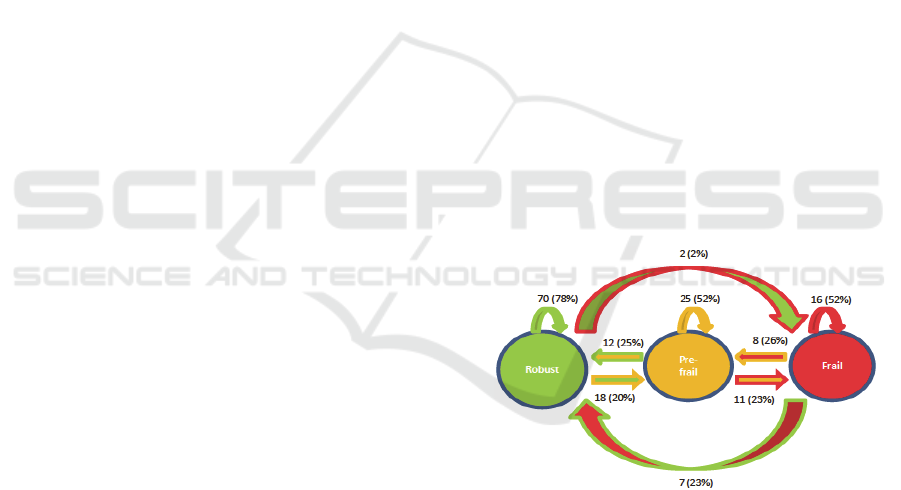

In all, 169 participants had completed the GFI at

baseline and end-point at the last follow-up. Of

these, 78% remained robust, while half remained

pre-frail or frail. One quarter transitioned from frail

to pre-frail and from pre-frail to robust. One fifth

converted from pre-frailty to established frailty.

These data are presented in Figure 2. The proportion

transitioning is higher than that reported previously

and likely represents differences in the way that data

is collected and a shorter period of follow-up. There

was no difference in overall ‘global’ frailty status as

measured by the GFI between those included in the

mcRCT as cases utilising the PERSSILAA training

modules and pre-frail controls, p<0.05. Twelve

community-dwelling older adults participated in the

monitoring feasibility sub-study. At baseline each

was surveyed to determine their self-reported

familiarity, comfort and level of daily use of ICT.

Over the following month their daily weight and

physical activity were measured and monitored

using the ‘smart scale’ and pedometer provided. At

the end a semi-structured interview was conducted.

Overall, compliance was modest with participants

stressing that ICT monitoring devices should be

designed with their needs in mind. Participants

stated that they were knew that maintaining a

healthy weight has benefits and enjoyed access to

healthy recipes.

Figure 2: Frailty transitions (n=169) for participants with

baseline & end-point Groningen Frailty Indicator scores.

Examining the cognitive domain, it was found

that older adults also enjoyed the ‘brain training’

games but do not want to be confronted or compared

with the results of peers. Likewise, older adults

stated that physical activity is important for overall

health.

These approaches to continuous ICT monitoring

showed mixed results and confirmed that older

adults while keen to engage technology for the

betterment of their health will only do so when it is

acceptable to them. Future studies should be

designed to study the effects and ultimately

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

98

incorporate health and ICT literacy in their designs.

Striking the balance between non-invasive

monitoring that is non-obtrusive and avoids

‘attention theft’ and more obvious strategies that

increase awareness of the need to engage with ICT

to prevent frailty and subsequent functional decline

will be the challenge.

Recommendation: There is likely to be no ‘one-

size-fits-all’ approach to monitoring older

community dwellers for pre-frailty. However, ICT

training is required for older adults in order for

them to engage with monitoring, particularly where

end-user feedback is required.

Recommendation: Monitoring of everyday

function must be complemented by meaningful

(older adult-specific) information to support the

adoption of healthier behaviours.

Recommendation: Technology to support the

prevention of functional decline must go beyond the

disease oriented-perspective and focus, instead, on

strategies to maintain independence in daily

activities.

Recommendation: When remotely monitoring

older adults health (pre-frailty) status using ICT

technologies, systems should provide feedback on

the data collected.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The results of the three-year, FP7 funded,

PERSSILAA project show the potential to use an

ICT-based, multi-domain service module to target

pre-frail older adults at risk of becoming frail and

developing functional decline. These results discuss

the healthcare recommendations that can be drawn

from the project and which could form the basis of a

European guideline on managing pre-frailty.

Specifically, PERSSILAA demonstrated the

acceptability and usability of this approach with

older adults, who may not find the use of such

technology easy (Scanlon, 2015), especially where

there is coexisting disability (Gell, 2015). To our

knowledge, this is the first paper to explore the use

of ICT with pre-frail, community-dwelling older

adults and the results showed that they rated the

three training modules (nutritional, cognitive and

physical) high for usability. This was similar for the

two distinct populations sampled: older Dutch

citizens attending primary care and older Italians

living in communities centred around their local

church. Only Portuguese citizens rated the

NUTRIAGEING

TM

website though it unlikely that

these differ considerably from other participants.

Another key finding of PERSSILAA is that health

literacy and ICT literacy are both important in

allowing older adults access such services. Older

Italians felt they benefited from the social

environment created by the classrooms provided.

Dutch participants however, preferred to train alone

and not compare results with their compatriots. This

may reflect different cultural backgrounds and

suggests that a one size fits all approach is unlikely

to be successful when integrating ICT into the every

day lives of older Europeans to improve their health

status. PERSSILAA is also one of the first studies to

study the effects of gamification (de Vette, 2015) on

older adults and how it may help engage them with

ICT training modules.

The results also highlight many of the challenges

of undertaking a study like this with a difficult

population to sample: pre-frail, older adults, who

while at risk for subsequent frailty and functional

decline may not be aware of this or motivated

enough to engage with screening processes. The

two-stage process enhanced the screening pathway

developed to recruit suitable participants. Several of

screens have excellent sensitivity though relatively

poor specificity meaning that a face-to-face

assessment was required to ensure that participants

were pre-frail. The results suggested that this

strategy was accurate. Due to resource limitations

not all those screening positive for pre-frailty had a

repeat assessment at the end-point of the study and

only a small number were monitored. The study was

also able to demonstrate frailty transitions during the

evaluation period but these may not be

representative of the true trajectory of frailty in this

population. Such proportionally high (approx. 20%)

transitions from one frailty state to another over a

short period are in contrast with data presented

elsewhere in larger samples over longer periods

(Gill, 2006). Therefore, it is likely that this reflects

the limitations of the screening and assessment

process itself, delivered both remotely and face-to-

face using validated instruments but not senior

physician/geriatrician assessment. However, this

project aimed to show the potential for lay or self-

screening, something that is likely to become more

widely accepted as healthcare becomes more

proactive and less reactive, stepping away from the

traditional medical model. Another limitation is that

only a small sample trialled the full platform,

released in stages as it was developed, which meant

that no significant impact upon GFI scores were

Healthcare Recommendations from the Personalised ICT Supported Service for Independent Living and Active Ageing (PERSSILAA)

Study

99

seen. This limits the project to the development and

evaluation of a service platform, which was the main

focus of the research. Thus, as a proof of concept

PERSSILAA shows the potential to use a multi-

domain ICT-based platform with older, pre-frail

adults. This, however, reduces the generalisability of

the results, which nevertheless present useful lessons

from both the development and implementation of

the platform

Overall, the 25 healthcare-related

recommendations presented provide guidance on

how to address the development and evaluation of

ICT supported services to tackle the emerging public

health challenge that an increasingly ageing and frail

older population represents. To our knowledge, this

is the first study to show the potential for an ICT

platform targeting key pre-frailty areas (i.e.

nutritional, cognitive and physical domains) in the

screening, monitoring and managing of pre-frailty.

The results of the evaluation are being analysed

further and future research is being planned to

validate the PERSSILAA platform with a suitably

powered RCT to determine if ICT-supported

services can truly prevent or delay onset of frailty

and functional decline in pre-frail community-

dwelling older adults.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank all the PERSSILAA

participants throughout the three years of the project.

Specifically , the authors thank - all older adults who

joined the project: for Italy this includes residents

from the Confalone, Pilar, Rogazionisti and Santa

Maria della Salute communities; for the Netherlands

this includes those in the municipalities of Enschede,

Hengelo, Tubbergen and Twenterand. The

researchers would also like to acknowledge the not

for profit organizations in Italy who collaborated

(Progetto Alfa, Saluta in Collina), the healthcare

professionals from Campania (Local Health Agency

Naples 1, CRIUV) and the health systems including

General Practitioners who supported the project in

the Netherlands.

REFERENCES

Beswick, A.D., Rees, K., Dieppe, P., Ayis, S.,

Gooberman-Hill, R., Horwood, J., Ebrahim, S. 2008.

Complex interventions to improve physical function

and maintain independent living in elderly people: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 371,

725-735.

Bherer, L., Erickson, K.I., Liu-Ambrose, T. 2013. A

review of the effects of physical activity and exercise

on cognitive and brain functions in older adults.

Journal of aging research, 11;2013.

Bitterman, N., 2011. Design of medical devices—A home

perspective. European journal of internal

medicine, 22(1), pp.39-42.

Boehler, C.E., de Graaf, G., Steuten, L., Yang, Y.,

Abadie, F. 2015. “Development of a web-based tool

for the assessment of health and economic outcomes

of the European Innovation Partnership on Active and

Healthy Ageing (EIP on AHA),” BMC Med. Inform.

Decis. Mak 15 (S3), p. S4.

Borges, L.L. and Menezes, R.L., 2011. Definitions and

markers of frailty: a systematic review of literature.

Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 21(01), pp.67-77.

Bousquet, J., Michel, J.P., Strandberg, T., Crooks, D.,

Iakovidis, I., Iglesia, M. 2014. The European

innovation partnership on active and healthy ageing:

the European geriatric medicine introduces the EIP on

AHA column. Eur Geriatr Med 5:361–362.

Brooke, J. 1996. "SUS: a "quick and dirty" usability

scale". In P. W. Jordan, B. Thomas, B. A.

Weerdmeester, & A. L. McClelland. Usability

Evaluation in Industry. London: Taylor and Francis.

Bunt, S., O’Caoimh, R., Krijnen, W.P., Molloy, D.W.,

Goodijk, G.P., van der Schans, C.P., Hobbelen, J.S.M.

2015. Validation of the Dutch version of the Quick

Mild Cognitive Impairment Screen (Qmci-D). BMC

Geriatrics 15:115 DOI 10.1186/s12877-015-0113-1.

de Vette, F., Tabak, M., Dekker-van Weering, M.,

Vollenbroek-Hutten, M. 2015. Engaging Elderly

People in Telemedicine Through Gamification. JMIR

Serious Games, 3(2):e9.

de Vries, N.,M., Staal, J.,B., van Ravensberg, C.,D.,

Hobbelen, J.,S.,M., Olde Rikkerte, M.,G.,M., Nijhuis-

van der Sanden, M.,W.,G. 2011. Outcome instruments

to measure frailty: A systematic review. Ageing

Research Reviews, 10: 104–114.

Fairhall, N., Kurrle, S.E., Sherrington, C., Lord, S.,R.,

Lockwood, K., John, B., Monaghan, N., Howard, K.,

Cameron, I,.D. 2015. Effectiveness of a multifactorial

intervention on preventing development of frailty in

pre-frail older people: study protocol for a randomised

controlled trial. BMJ Open. 5(2):e007091.

Fiatarone Singh, M.A., Gates, N., Saigal, N., et al. 2014.

The Study of Mental and Resistance Training

(SMART) study-resistance training and/or cognitive

training in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized,

double-blind, double-sham controlled trial. J Am Med

Dir Assoc, 15(12): 873–80.

Galvin, J.E., Roe, C.M., Powlishta, K.K., Coats, M.A.,

Muich, S.J., Grant, E., Miller, J.P., Storandt, M. and

Morris, J.C., 2005. The AD8 A brief informant

interview to detect dementia. Neurology, 65(4);

pp.559-564.

Gell, N.,M., Rosenberg, D.,E., Demiris, G., LaCroix,

A.,Z., Patel, K.,V. 2015. Patterns of technology use

among older adults with and without disabilities.

Gerontologist, 55(3):pp412-21.

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

100

Gill, T.M., Gahbauer, E.A., Allore, H.G, Han, L. 2006.

Transitions between frailty states among community-

living older persons. Arch Intern Med, 166(4):418-23.

Giné-Garriga, M., Roqué-Fíguls, M., Coll-Planas, L.,

Sitjà-Rabert, M., Salvà, A. 2014. Physical Exercise

Interventions for Improving Performance-Based

Measures of Physical Function in Community-

Dwelling, Frail Older Adults: A Systematic Review

and Meta-Analysis. Archives of physical medicine and

rehabilitation, 95 (4):pp 753–769.e3.

Gray, S.L, Anderson, M.L, Hubbard, R.A., LaCroix, A.,

Crane, P.K., McCormick, W., Bowen, J.D, McCurry,

S.M., Larson, E.B. 2013. Frailty and incident

dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 68(9):1083-

90.

Illario, M., Iaccarino, G., Piazza, O., Menditto, E.,

Coscioni, E. 2016. Proceedings of the EIP on AHA:

A3 Action Group on Frailty. Transl Med UniSa.

31;13:1-3.

Kahlon, S., Pederson, J., Majumdar, S.R., Belga, S., Lau,

D., Fradette, M., Boyko, D., Bakal, J.A., Johnston, C.,

Padwal, R.S. and McAlister, F.A., 2015. Association

between frailty and 30-day outcomes after discharge

from hospital. Canadian Medical Association

Journal, 187(11): pp.799-804.

Lang, P.O., Michel, J.P., Zekry, D. 2009. Frailty

syndrome: a transitional state in a dynamic process.

Gerontology, 55(5):539-49.

Langa, K.M., Larson, E.B., Crimmins, E.M., et al. 2016. A

comparison of the prevalence of dementia in the

United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Intern Med

doi:10.1001 /jamainternmed.2016.6807

Larner, A.J., 2015. AD8 Informant Questionnaire for

Cognitive Impairment Pragmatic Diagnostic Test

Accuracy Study. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and

neurology, 28(3): pp.198-202.

Lee, P.H., Lee, Y.S., Chan, D.C. 2012. Interventions

targeting geriatric frailty: a systemic review. Journal

of Clinical Gerontology and Geriatrics, 3(2):47-52.

Liu, C.K. and Fielding, R.A., 2011. Exercise as an

intervention for frailty. Clinics in geriatric medicine,

27(1), pp.101-110.

Liu, L.K., Lee, W.J., Chen, L.Y., Hwang, A.C., Lin, M.H.,

Peng, L.N. and Chen, L.K., 2015. Association between

frailty, osteoporosis, falls and hip fractures among

community-dwelling people aged 50 years and older

in Taiwan: results from I-Lan longitudinal aging

study. PLoS one, 10(9), p.e0136968.

Lumsden, J., Edwards, E.A., Lawrence, N.S., Coyle, D.

and Munafò, M.R., 2016. Gamification of cognitive

assessment and cognitive training: a systematic review

of applications and efficacy. JMIR Serious Games,

4(2).

Manafo, E., Wong., S. 2012. Health literacy programs for

older adults: a systematic literature review. Health

Educ Res. 27(6):947-60.

Matthews, F.E., Arthur, A., Barnes, L.E., et al. 2013.

Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and

Ageing Collaboration. A two-decade comparison of

prevalence of dementia in individuals aged 65 years

and older from three geographical areas of England:

results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I

and II. The Lancet, 382(9902):1405-1412.

Michel, J.P., Dreux, C., Vacheron, A. 2016. Healthy

ageing: evidence that improvement is possible at every

age. European Geriatric Medicine, 7(4), pp.298-305.

Morley, J.E., Vellas, B., van Kan, G.A., et al. 2013. Frailty

consensus: a call to action. Journal of the American

Medical Directors Association 14:392–7.

Ngandu, T., Lehtisalo, J., Solomon, A., Levälahti, E.,

Ahtiluoto, S., Antikainen, R., Bäckman, L., Hänninen,

T., Jula, A., Laatikainen, T. and Lindström, J., 2015. A

2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise,

cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus

control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly

people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. The

Lancet, 385(9984), pp.2255-2263.

Norman, C., Skinner, H. 2006. eHealth literacy: Essential

skills for consumer health in a networked world. J

Med Internet Res, 8:e9.

O’Caoimh, R., Gao, Y., McGlade, C., Healy, L.,

Gallagher, P., Timmons, S., Molloy, D.W. 2012.

Comparison of the Quick Mild Cognitive Impairment

(Qmci) screen and the SMMSE in Screening for Mild

Cognitive Impairment. Age and Ageing 41(5):624-9.

O’Caoimh, R., Gao, Y., Gallagher, P., Eustace, J.,

McGlade, C., Molloy, D.W. 2013. Which Part of the

Quick Mild Cognitive Impairment Screen (Qmci)

Discriminates Between Normal Cognition, Mild

Cognitive Impairment and Dementia? Age and Ageing

42: 324-330.

O’Caoimh, R., Svendrovski, A., Johnston, B., Gao, Y.,

McGlade, C., Timmons, S., Eustace, J., Guyatt, G.,

Molloy, D.W. 2014a. The Quick Mild Cognitive

Impairment Screen correlated with the Standardised

Alzheimer`s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive

section in clinical trials. Journal of Clinical

Epidemiology 67, 87-92.

O’Caoimh, R., Gao, Y., Svendrovski, A., Healy, E.,

O’Connell, E., O’Keeffe, G., Leahy-Warren, P.,

Cronin, U., O’Herlihy, E., Cornally, N., Molloy, D.W.

2015a. The Risk Instrument for Screening in the

Community (RISC): A New Instrument for Predicting

Risk of Adverse Outcomes in Community Dwelling

Older Adults. BMC Geriatrics 15:92. doi:

10.1186/s12877-015-0095-z.

O’Caoimh, R., Sweeney, C., Hynes, H. et al. 2015b.

COLLaboration on AGEing – COLLAGE: Ireland's

three star reference site for the European Innovation

Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP on

AHA). Eur Geriatr Med 6:505–511.

O’Caoimh, R., Sato, S., Wall, J., Igras, E., Foley, M.J.,

Timmons, S., Molloy, D.W. 2015c. Potential for a

"Memory Gym" Intervention to Delay Conversion of

Mild Cognitive Impairment to Dementia. Journal of

the American Medical Directors Association 16 (11),

pp.998-999.

O’Caoimh, R., Timmons, S., Molloy, D.W. 2016.

Screening for Mild Cognitive Impairment:

Healthcare Recommendations from the Personalised ICT Supported Service for Independent Living and Active Ageing (PERSSILAA)

Study

101

Comparison of "MCI Specific" Screening Instruments.

Journal of Alzheimer’s disease 51(2):619-29.

O’Caoimh, R., Gao, Y., Gallagher, P., Eustace, J., Molloy,

W. 2017. Comparing Approaches to Optimize Cut-off

Scores for Short Cognitive Screening Instruments in

Mild Cognitive Impairment and Dementia. Journal Of

Alzheimer’s Disease, in press.

O’Shea, E., Trawley, S., Manning, E. et al. 2016.

Malnutrition in hospitalised older adults: A

multicentre observational study of prevalence,

associations and outcomes J Nutr Health Aging

doi:10.1007/s12603-016-0831-x

Pahor, M., Guralnik, J.M., Ambrosius, W.T., Blair, S.,

Bonds, D.E., Church, T.S., Espeland, M.A., Fielding,

R.A., Gill, T.M., Groessl, E.J. and King, A.C. 2014.

Effect of structured physical activity on prevention of

major mobility disability in older adults: the LIFE

study randomized clinical trial. Jama, 311(23),

pp.2387-2396.

Pauly, L., Stehle, P., Volkert, D. 2007. Nutritional

situation of elderly nursing home residents. Z Gerontol

Geriatr 40(1):3-12.

Peters, L.L., Boter, H., Slaets, J.P., Buskens, E. 2013.

Development and measurement properties of the self

assessment version of the INTERMED for the elderly

to assess case complexity. Journal of Psychosom Res

;74(6):518-522.

Plassman, B.L., Langa, K.M., Fisher, G.G., Heeringa,

S.G., Weir, D.R., Ofstedal, M.B., Burke, J.R., Hurd,

M.D., Potter, G.G., Rodgers, W.L. and Steffens, D.C.,

2008. Prevalence of cognitive impairment without

dementia in the United States. Annals of internal

medicine, 148(6), pp.427-434.

Prince, M., Bryce, R., Albanese, E., Wimo, A., Ribeiro,

W., Ferri, C.P. 2013. The global prevalence of

dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Alzheimers Dementia, 9(1):63-75.

Rechel, B., Grundy, E., Robine, J.M., Cylus, J.,

Mackenbach, J.P., Knai, C., et al. 2013. Ageing in the

European Union. The Lancet, 381(9874):1312–22.

Robertson, M.C., Devlin, N., Scuffham, P., Gardner,

M.M., Buchner, D.M., Campbell, A.J. 2001.

Economic evaluation of a community based exercise

programme to prevent falls. J Epidemiol Community

Health 55:600-606.

Rodríguez-Mañas, L., Féart, C., Mann, G., Viña, J.,

Chatterji, S., Chodzko-Zajko, W., Harmand, M.G.,

Bergman, H., Carcaillon, L., Nicholson, C., Scuteri, A.

2013. Searching for an operational definition of frailty:

a Delphi method based consensus statement. The

frailty operative definition-consensus conference

project. The Journals of Gerontology Series A:

Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 68(1):62-7.

Roe, L., O’Halloran, A., Normand, C., Murphy, C. 2016.

The impact of frailty on public Health Nurse Service

Utilisation: Findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study

On Ageing (TILDA).

Santos-Eggimann, B., Cuenoud, P., Spagnoli, J., Junod, J.

2009. Prevalence of Frailty in Middle-Aged and Older

Community-Dwelling Europeans Living in 10

Countries. Journals of Gerontology Series a-

Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences

, 64, 675-

681.

Satizabal, C.L., Beiser, A.S., Chouraki, V., Chêne, G.,

Dufouil, C., Seshadri, S.2016. Incidence of dementia

over three decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N

Engl J Med, 374(6):523-532.

Scanlon, L., O’Shea, E., O’Caoimh, R., Timmons, S.

2015. Technology use, frequency and self-rated skills:

A survey of community dwelling older adults. Journal

of American Geriatrics Society 63(7):1483-4.

Schilp, J., Kruizenga, H.M., Wijnhoven, H.A., Leistra, E.,

Evers, A.M., van Binsbergen, J.J., Deeg, D.J. and

Visser, M., 2012. High prevalence of undernutrition in

Dutch community-dwelling older individuals.

Nutrition, 28(11), pp.1151-1156.

Selwyn, N., Gorard, S., Furlong, J. and Madden, L., 2003.

Older adults' use of information and communications

technology in everyday life. Ageing and society,

23(05), pp.561-582.

Sergi, G., Veronese, N., Fontana, L., De Rui, M., Bolzetta,

F., Zambon, S., Corti, M.C., Baggio, G., Toffanello,

E.D., Crepaldi, G. and Perissinotto, E. 2015. Pre-

frailty and risk of cardiovascular disease in elderly

men and women: the Pro. VA study. Journal of The

American college of cardiology, 65(10), pp.976-983.

Shakersain, B., Santoni, G., Faxén-Irving, G., Rizzuto, D.,

Fratiglioni, L., Xu, W. 2016. Nutritional status and

survival among old adults: an 11-year population-

based longitudinal study. European Journal of

Clinical Nutrition, 70, 320-325.

Song, X., Mitnitski, A., Rockwood, K. 2010. Prevalence

and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in

relation to deficit accumulation. J Am Geriatr Soc

58(4):681-7.

Sternberg, S.A., Schwartz, A.W., Karunananthan, S.,

Bergman, H., Clarfield, A.M. 2011. The Identification

of Frailty: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of

the American Geriatrics Society, 59, 2129-2138

Steverink, N., Slaets, J.P.J., Schuurmans, H., Van Lis, M.

2001. Measuring frailty: developing and testing the

GFI (Groningen Frailty Indicator). Gerontologist.

2001;41(Special Issue 1):236.

Strawbridge, W.,J., Shema, S.,J., Balfour, J.,L., Higby,

H.,R., Kaplan, G.,A. 1998. Antecedents of frailty over

three decades in an older cohort. J Gerontology

53b(1);ppS9-16.

Tabak, M., Brusse-Keizer, M., van der Valk, P., Hermens,

H. and Vollenbroek-Hutten, M. 2014. A telehealth

program for self-management of COPD exacerbations

and promotion of an active lifestyle: a pilot

randomized controlled trial. International journal of

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 9, p.935.

Thomas, S., Mackintosh, S. and Halbert, J. 2010. Does the

‘Otago exercise programme’reduce mortality and falls

in older adults?: a systematic review and meta-

analysis. Age and Ageing, 39(6):pp681-7.

Turner, G., Clegg, A; British Geriatrics Society; Age UK;

Royal College of General Practioners. 2014. Best

practice guidelines for the management of frailty: a

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

102

British Geriatrics Society, Age UK and Royal College

of General Practitioners report. Age and Ageing,

43(6):pp744-7.

van Kempen, J.A., Schers, H.J., Philp, I., Rikkert, M.G.O.

and Melis, R.J., 2015. Predictive validity of a two-step

tool to map frailty in primary care. BMC

medicine, 13(1), p.1.

van Staveren, W.A. and de Groot, L.C.P. 2011. Evidence-

based dietary guidance and the role of dairy products

for appropriate nutrition in the elderly. Journal of the

American College of Nutrition, 30(sup5), pp.429S-

437S.

Vollenbroek-Hutten, M., Pais, S., Ponce, S., Dekker-van

Weering, M., Jansen-Kosterink, S., Schena, F.,

Tabarini, N., Carotenuto, F., Iadicicco, V. and Illario,

M. 2015. Rest Rust! Physical active for active and

healthy ageing. Translational medicine@ UniSa, 13,

p.19.

Healthcare Recommendations from the Personalised ICT Supported Service for Independent Living and Active Ageing (PERSSILAA)

Study

103