Helpful but Spooky? Acceptance of AAL-systems Contrasting User

Groups with Focus on Disabilities and Care Needs

Julia van Heek, Simon Himmel and Martina Ziefle

Human-Computer Interaction Center, RWTH Aachen, Campus-Boulevard 57, 52064 Aachen, Germany

Keywords: Ambient Assisted Living, Technology Acceptance, User Diversity, Age, Needs of Care, Needs of

Assistance, Disabled People.

Abstract: Ambient Assisted Living (AAL) technologies present one approach facing the challenges of recent and

rising care needs due to demographic changes in western societies. Beside the technological implementa-

tion, the focus on user acceptance of all stakeholders plays a major role for a successful rollout. As most re-

search deals with age-related issues, this paper emphasizes especially on the sector of disabled persons. In a

qualitative interview pre-study (n=9) and a validating questionnaire study (n=279) the perceived benefits

and barriers of AAL technologies were contrasted in four user groups: healthy “not-experienced” people,

disabled, their relatives, and professional care givers. Results indicate that disabled and care-needy people

show a higher acceptance and intention to use an AAL system than “not-experienced” people or care givers

and that the motives for use and non-use differ strongly with regard to user diversity as well. The results

show the importance to integrate diverse user groups (age, disabilities) into the design and evaluation pro-

cess of AAL technologies.

1 INTRODUCTION

Demographic change represents one of the major

challenges for today’s society. A constantly increas-

ing number of older people and people in need of

care poses exceptional burdens for the care sector

(Bloom & Canning, 2004; Walker & Maltby, 2012).

Concurrently, in particular most of the older people

desire to live at their own home as long as possible

and as autonomously as possible (Wiles et al., 2011).

Age and age-related diseases (e.g., diabetes, de-

mentia, cardiovascular diseases) are enormously

important and increase steadily (Shaw et al., 2010;

Wild et al., 2004; Roger et al., 2011), but represent

only one side of the coin. Age-independent diseases

and disabilities are also of importance and should be

considered as they cause huge needs of care and

assistance as well (Geenen et al., 2003). Additional-

ly, there is the comparably new phenomenon of “old

disabled” people, on the one hand, due to medical

and technical developments in healthcare concerning

new innovative medicines and therapies. On the

other hand, especially in Europe - due to the specific

historical background of euthanasia offenses, in

which disabled people were systematically aborted,

deported, and even murdered (Poore, 2007).

Hence, age, diseases, and disabilities are all rele-

vant factors that have to be considered with regard to

increasing needs of care and related challenges. In

the last decades it is tried to face these challenges

developing various technical single-case solutions

but also complex ambient assisted living systems

(AAL) (Schmitt, 2002).

A huge amount of systems exist that monitor

medical parameters or detect falls as well as facili-

tate living at home using smart home technology

elements (Cheng et al., 2013; Baig & Gholamhos-

seini, 2013; Rashidi & Mihailidis, 2013). Beyond

multiply available single solutions, current research

focuses also on holistic AAL systems, that combine

various functions and are ideally cost-effective,

retrofittable, and adaptable to the individual needs of

diverse user groups.

In particular with regard to different user groups,

the question arises whether and to which extent such

AAL systems are desired and accepted. Which fac-

tors are crucial for acceptance and to what extent

does this evaluation depend on user factors?

Several studies investigate the acceptance of

such and similar technologies focussing on age (e.g.,

Fuchsberger, 2008; Demiris et al. 2008) or gender

(Wilkowska et al., 2010) as presumed influencing

78

Heek, J., Himmel, S. and Ziefle, M.

Helpful but Spooky? Acceptance of AAL-systems Contrasting User Groups with Focus on Disabilities and Care Needs .

DOI: 10.5220/0006325400780090

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health (ICT4AWE 2017), pages 78-90

ISBN: 978-989-758-251-6

Copyright © 2017 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

factors. As disabled people have hardly been consid-

ered so far, this paper investigates the acceptance of

AAL systems with focus on people having experi-

ences with disabilities in different perspectives.

2 AAL & ACCEPTANCE

First, the state of the art concerning AAL technolo-

gies is shortly summarized. Afterwards, the theoreti-

cal background of technology acceptance research is

presented focusing on the influence of user diversity

factors. Further, an overview of current acceptance

research on AAL systems is given.

2.1 AAL Technologies

The use of Information and Communication Tech-

nologies (ICT) in everyday life has been studied

since the 1980s (Silverstone et al., 1989). Different

types of monitoring are enabled by integrating ICT

(e.g., microphones, cameras, and movement sensors)

into people’s living environments. In recent years,

the number of commercially available AAL systems

as well as AAL research projects increased signifi-

cantly. In this context, retrofittable, modularly con-

structed (as required), and multifunctional systems

are offered including -among others - smart home

functions (such as sensors for control of lighting,

heating, doors, and windows), fall detection, and

other health care applications like providing of and

reminder for drugs or blood sugar measuring. These

systems are available for an integration in the home

environment (e.g., Casenio, 2016; Essence, 2016), in

hospitals (EarlySense, 2016), and in nursing homes

(Tunstall, 2016).

Besides commercial solutions, research projects

also focus on the development of holistic AAL sys-

tems (e.g., Sixsmith et al., 2009; Gövercin et al.,

2016). However, in contrast to most of the commer-

cial solutions, these projects attach importance to

consider future users (mainly older people) iterative-

ly in the development process of the AAL system

(Kleinberger et al., 2007). This is of significance in

as much as the user’s perspective is decisive for a

successful integration of AAL systems in their eve-

ryday life. Currently, AAL technologies are not

widely integrated in private home environments,

although they have the potential to facilitate the

everyday life of older, diseased, or disabled people.

To understand the barriers of AAL usage, we have

to focus on potential users of these systems, their

perception, ideas, wishes, and their willingness to

adopt home-integrated ICT.

2.2 Technology Acceptance, User Di-

versity & AAL Systems

AAL technologies as a possible solution for the

challenges of the demographic change were mostly

perceived and evaluated positive and the necessity

and usefulness of technical support were also highly

acknowledged (Beringer et al., 2011; Gövercin et al.,

2016). In particular, the opportunity of staying long-

er at the own home and an independent life are

strong motives to use (or imagine to use) an AAL

system. On the other hand, restraints and acceptance

barriers such as feelings of isolation (e.g., Sun et al.,

2010), feelings of surveillance, and invasion of pri-

vacy (e.g., Wilkowska et al., 2015) were frequently

mentioned when asking people to think about a

concrete implementation of an AAL system in their

living environment.

To understand this trade-off it is necessary to

consider both user diversity and technology ac-

ceptance. In the last years, research became more

aware of the limited suitability of traditional tech-

nology acceptance models like TAM or UTAUT as -

in contrast to conventional ICT - AAL systems ad-

dress especially older, diseased, and frail people

with individual requirements, wishes, and concerns

(Kowalewski et al., 2012). We assume that this con-

currently leads to a different weighting of important

perceived benefits and barriers and a different ac-

ceptance of using an AAL system. Therefore, an

overview of acceptance research findings focusing

on user diversity and different user group perspec-

tives is presented.

2.2.1 Factor Age

The benefits and barriers of AAL technologies for

elderly are widely discussed and researched in the

last decade. To understand the perception of AAL

technologies, numerous focus groups (Demiris et al.,

2004; Ziefle et al., 2011) and interviews (Beringer et

al., 2011) with people aged above 60 show similar

results: elderly remark the benefits of staying at

home longer, understand the imminent lack of care

nurses and the chances of AAL technologies. On the

other side, they fear dependency on technologies

they cannot control, the lack of personal contact,

demur data and privacy concerns. Plentiful surveys

verify these qualitative gained results over time

(e.g., Himmel & Ziefle, 2016). However, the meas-

urement of attitudes towards technologies strongly

depends on the research method and hands-on expe-

rience in real-life scenarios is inevitable to under-

stand older peoples’ actual approach to AAL tech-

Helpful but Spooky? Acceptance of AAL-systems Contrasting User Groups with Focus on Disabilities and Care Needs

79

nologies (Wilkowska et al., 2015). While several

projects for ambient intelligence and ubiquitous

computing in smart homes focused mainly on the

technological implementations, recent projects on

AAL labs, e.g., Philips Research CareLab (de Ruyter

& Pelgrim, 2007), SOPRANO (Sixsmith et al.,

2009), eHealth Future Care Lab (Brauner et al.,

2015), to mention but a few, have understood to

implement the user into the design and evaluation

circle. The role of acceptance, the influence of pri-

vacy and trust, especially of elderly users, is there-

fore extensively investigated.

2.2.2 Factors Diseases & Disabilities

While research for AAL technologies emphasized

on elderly people with age-related chronic or physi-

cal illnesses, the acceptance of AAL technologies

for disabled persons still needs more and specified

research attention. On the one hand, assistive tech-

nologies could improve the inclusion of people with

disabilities into society, supporting mobility, and

communication as well as holding down a job. On

the other hand, age-related illnesses come along with

already existing disabilities, which is as already

mentioned a quite new phenomenon (Poore, 2007).

Regarding the care sector, besides pediatric nurs-

ing, ageing, diseases, and disabilities are the three

central challenges. Frequently, age, diseases, and

disabilities are summed up and neither investigated

in depth nor separately. How different diseases and

disabilities affect the use of medical technology is

investigated and summarized in occasional studies

(e.g., Harris, 2010; Gentry, 2009). These studies try

to analyze why numerous existing technologies are

abandoned and lie unused. The problem is that re-

search on AAL technology acceptance of diseased or

disabled people is partly comparatively unspecific,

superficial, and on a theoretical level. We assume,

this is mainly due to the fact that especially disabled

people are considered and directly asked for their

opinions, whishes, and needs only in few cases.

However, this is precisely where research is re-

quired: especially disabled people have to be inte-

grated in the design of assistive technologies and the

interaction of age, diseases, and disabilities has to be

focused as these factors constitute the major part of

care needs.

To do especially justice to needs of care and care

in itself, the perspectives of professional care givers

or family care givers have to be considered as well.

Within the research landscape concerning AAL

technologies and their perception, some studies

examined the requirements and professional and

family caregivers’ perspectives on AAL systems and

technologies separately and not comparatively

(López et al., 2015; Mortenson et al., 2013). In these

studies, the effectiveness of different technologies is

focused and guidelines for design and implementa-

tion are derived. Single studies try to concentrate on

the user (care givers and patients) and perceived

concerns regarding in-home monitoring technologies

(Larizza et al., 2014). These studies deliver first

insights into different perspectives on the acceptance

of AAL technologies. However, they do not allow to

directly compare the perspectives of “patients” (old-

er, diseased, or disabled people) with family or pro-

fessional care givers and “not-experienced” people,

as they were each mainly focused on a specific user

group and no equivalent or comparable methodolog-

ical approach was used for the user groups.

So far, there is only little knowledge about the

acceptance of AAL technologies with regard to

disabled people and people with special care needs,

about the interaction of the described user factors

(age, diseases, and disabilities, needs in assistance

and care) as well as about the perspectives of differ-

ent user groups (affected themselves, relatives and

families of people need in care, professional care-

givers). Therefore, these interactions were addressed

in the present study.

3 METHOD

In this section, the research design is presented start-

ing with a short summary of the qualitative inter-

view study, which was taken as a basis for the sub-

sequent quantitative study. Afterwards, the empirical

design of the quantitative study and the sample’s

characteristics are detailed. We choose a multi-

method approach for this study consisting of a quali-

tative interview study and a consecutive quantitative

questionnaire study. Our study addresses three es-

sential research questions:

1. How do the participants evaluate a holistic AAL

system (see 3.3) and which perceived benefits

and barriers are most important for its ac-

ceptance?

2. To which extent do age, experiences with disa-

bilities, and current care needs influence the

AAL system’s evaluation?

3. Are different benefits and barriers decisive for

AAL acceptance depending on diverse user

group perspectives?

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

80

3.1 Research Design

As it was detailed in chapter 2, research on the ac-

ceptance of AAL technologies mostly focused on

older users so far. In contrast, there is only sparse

knowledge about developing AAL technologies for

people with disabilities and rarely research on the

acceptance of AAL technologies focusing on disa-

bled users. Further, other perspectives (e.g., profes-

sional caregivers, relatives, and families of disabled

people) are also of prime importance as they can

support and complete the understanding of potential

user’s needs and wishes. Hence, a qualitative inter-

view study was initially necessary to identify per-

ceived motives and barriers of use as well as use

conditions. Only based on these results it was rea-

sonable to design and conduct a quantitative study

focusing on people having experiences with disabili-

ties (themselves, families and relatives, professional

caregivers).

3.2 Qualitative Pre-study

A preceding interview study was conducted focusing

on people with disabilities (n=7), their relatives

(n=1), and a professional caregiver (n=1) and the

interviews took between 40 and 70 minutes. As the

quantitative study and results should be focused in

this paper (especially perceived benefits and barriers

of AAL systems), only the results of the qualitative

study are presented which were essential for the

conception of the quantitative questionnaire. With

regard to the described holistic AAL-system (scenar-

io similar as detailed in 3.3), the participants dis-

cussed 11 different benefits and 9 potential usage

barriers (Table 1).

These results align with previous research con-

cerning several aspects (e.g., comfort, facilitating

everyday life (e.g., Himmel et al., 2013)), but, to a

larger extent, the results are multifaceted and go

beyond previous findings due to the reference to

disabilities and constraints (e.g., compensation,

reduce confrontation with care needs, to be afraid of

isolation). Hence, these aspects have to be examined

quantitatively to be able to do justice to diverse user

groups.

Further, the participants evaluated the described

AAL system differently: the related person and the

caregiver assessed the scenario rather negative and

critical using words like spooky, lonely, inhuman,

not self-determined, and personal rights; in contrast,

the disabled participants associated it with more

positive and fascinated words such as exciting, luxu-

ry, very useful, helpful and comfortable. These re-

sults showed the importance of differentiating be-

tween different user groups and their considering in

the subsequent study.

Table 1: Overview of discussed benefits and potential

barriers of AAL systems in the interview study.

Perceived Benefits Potential Usage Barriers

Expansion of autonomy Isolation due to the substitution

of care staff by technologies

Reduction of dependency from

others

No real time savings (spend

more time on technology use)

Facilitating the everyday life Only if needed (doing as much

as possible autonomously)

Saving of time Missing relevance as care needs

are often too high

Comfort Functional incapacity (failure

of technology)

Reduction of confrontation with

own care needs

Feeling of surveillance

Increase the feeling of safety Too large proportion of tech-

nology in everyday life

Staying longer at the own home Expectation of a too complicat-

ed handling

Relief of family, relatives, and

caregivers

Transmission of false infor-

mation (e.g., false alarm)

Compensation of mobility

constraints

Enabling a fast data access

3.3 Questionnaire of Quantitative

Study

The questionnaire items were developed based on

the findings of the previous interview study. The

questionnaire consisted of different parts, while the

first part addressed demographic aspects, such as

age, gender, educational level, and income.

In the next part, the participants were asked for

their experiences with disabilities by indicating if

themselves are disabled (1), if they are related to a

disabled person (2), if they are the caregiver of a

disabled person (3), or if they have no experiences

with disabilities (4). Afterwards, the participants

were asked to indicate, whether and to which extent

(care time, type of care, intensity of care) themselves

(1+4) or the person they put themselves in position

with (2+3) is in need of care.

To ensure that all participants pertain to the same

baseline with regard to the evaluation of an AAL

technology, a scenario was designed. Depending on

their background (need of care, experience with

disabilities), the participants were introduced to the

scenario differently. For cases 2-4, the participants

were asked to put themselves in the / a disabled

person’s position (respectively the person they are

related with or they care (2+3)) while answering the

questions concerning the AAL scenario. Participants

who indicated to be not in need of care were asked

to imagine that they would be in need of care.

Helpful but Spooky? Acceptance of AAL-systems Contrasting User Groups with Focus on Disabilities and Care Needs

81

The scenario was designed as a very personal

everyday situation wherein the participants should

imagine that an specific, invisible AAL system was

integrated in their home environment and contained

the following functions: setting of the home temper-

ature (via smartphone), automatic opening and clos-

ing of (front) doors and windows (via sensors), au-

tomatic lighting control (via light sensors and posi-

tion localization), hands-free kit for phoning (inte-

grated microphones), monitoring of front door area

(via cameras), and fall detection (sensors in floor

and bed).

Afterwards, they had to evaluate a list of use

conditions, perceived benefits (11 items) of the AAL

system (e.g., to increase autonomy, to reduce de-

pendency on others, to facilitate everyday life, to

relieve fellow people), and perceived barriers (9

items) (e.g., feeling of surveillance, no trust in func-

tionality, to assume a too difficult usage, to be afraid

of isolation) based on the findings of the qualitative

interview study (see 3.2).

Following that, the participants should assess 8

statements regarding the acceptance or rejection of

the described AAL system as well as the behavioural

intention to use such an AAL system. All described

items had to be evaluated on six-point Likert scales

(1 = min: ”I strongly disagree”; 6 = max: “I strongly

agree”).

Finally, the participants were able to reason their

opinions towards the described AAL system on an

optional basis and to provide their feedback concern-

ing the questionnaire and the topic itself. Complet-

ing the questionnaire took on average 15 minutes

and data was collected in an online survey in Ger-

many. Overall, the questionnaire was made available

for 6 weeks in summer 2016.

3.4 Sample Description

A total of 279 participants volunteered to participate

in our questionnaire study, which was distributed

online in social network forums and acquired by

personal contact. Since only complete data sets

could be used for statistical analyses, a sample of

n=182 remained. The participants (62.1% female,

36.3% male, 1.6% no answer) were on average 38.7

years old (SD=13.95; min=20; max=81) and highly

educated with 46.7% holding a university degree

and 14.8% a university entrance diploma. Concern-

ing experience with disabilities, 51 participants indi-

cated to be disabled (28.0%), 12.1% (n=22) were

professional caregivers, 35 participants were rela-

tives of a disabled person (19.2%), and 40.7%

(n=74) had no experience with disabilities. Regard-

ing current needs of assistance and care, 79 (43.4%)

participants indicated to need care or that the person

- they put themselves in position with - needed care

(56.6% were not in need of care). These factors are

related only partially: age is not related with experi-

ence with disabilities (r=-.132; p=.075 >.05) nor

with current care needs (r=-.096; p=.197 >.05). In-

stead, age is related with gender (r=.200; p=.007

<.05; 1=female; 2=male). Not surprisingly, experi-

ence with disabilities correlates with current care

needs (r=.607; p=.000 <.05). Further, the partici-

pants reported to have on average a positive tech-

nical self-efficacy (M=4.5; SD=1.0; min=1; max=6)

and a slightly positive attitude towards technology

innovations (M=3.9; SD=1.0; min=1; max=6). Fur-

ther, they indicated their needs for data security

(M=4.1; SD=0.8; min=1; max=6) and privacy

(M=4.4; SD=0.7; min=1; max=6), which both were

on average positive.

4 RESULTS

Prior to descriptive and inference analyses, item

analyses were calculated to ensure measurement

quality. Cronbach’s alpha > 0.7 indicated a satisfy-

ing internal consistency of the scales. Data was ana-

lysed descriptively, by linear regression analyses

and, with respect to the effects of user diversity, by

(M)ANOVA procedures. The level of significance

was set at 5%.

To analyse the impact of need of assistance and

care on perceived benefits, barriers, and acceptance,

we choose the factors age, experience with disabili-

ties, and acute care needs for further analysis. The

results are structured as follows: first, the results for

acceptance of AAL, perceived benefits, and per-

ceived barriers were presented for the whole sample.

In a second step, the influences of user-specific

characteristics on the perception of benefits and

barriers as well as acceptance of AAL are examined.

4.1 General Acceptance of AAL

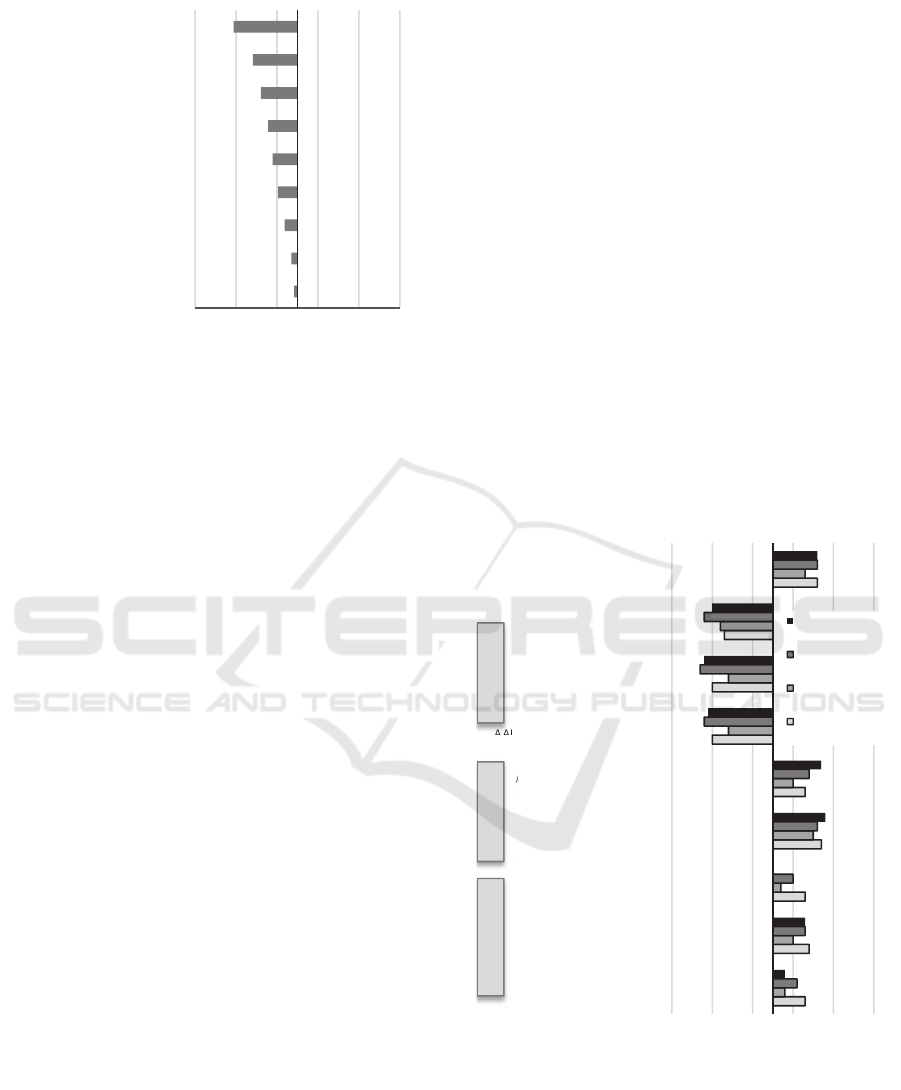

As it is shown in Figure 1, acceptance of AAL tech-

nologies was on average positive (M=4.6; SD=1.0).

In particular the items with regard to care needs

(…due to care needs (M=4.7; SD=1.1) and … re-

duce my care needs (M=4.5; SD=1.3) were evaluat-

ed highest. Three items concerning a concrete inten-

tion to use an AAL system were rated rather posi-

tive, while the item I would install… (M=4.3;

SD=1.4) was assessed higher than the aspects I like

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

82

to use… (M=4.0; SD=1.4) and I can imagine to

use…now (M=3.8; SD=1.6).

The three negative acceptance items were reject-

ed similarly (e.g., … AAL technologies are superflu-

ous (M=1.9; SD=1.1). As perceived benefits

(r=.433; p<.01) and perceived barriers (r=-.560;

p<.01) are both significantly related with ac-

ceptance, their evaluations are presented in detail for

the whole sample).

Figure 1: Evaluation of AAL system acceptance.

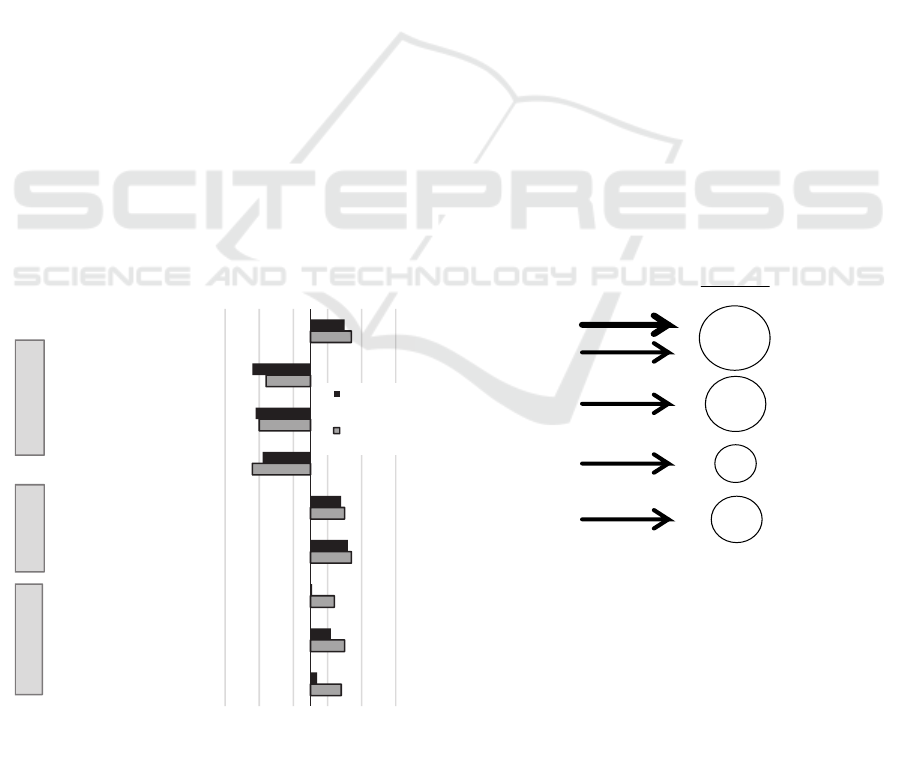

The evaluation of perceived benefits of the de-

scribed AAL system is shown in Figure 2 and obvi-

ously all aspects were assessed and perceived as

benefits as all values were above the mean of the

scale. The most important benefits were to facilitate

everyday life (M=5.2; SD=0.9), to expand own au-

tonomy (M=5.2; SD=1.0), to extend staying at home

(M=5.1; SD=1.0), and to reduce dependency from

other people (M=5.1; SD=1.0). The aspects to re-

lieve fellow people (M=4.9; SD=1.1), to compensate

reduced mobility (M=4.8; SD=1.0), comfort (M=4.7;

SD=1.2), and to increase the feeling of safety

(M=4.6; SD=1.3) were only little less important.

Comparatively, time savings (M=4.3; SD=1.4), to

enable fast data access (M=4.0; SD=1.4), and to

reduce own conflict with care needs (M=3.9;

SD=1.4) were minor important.

Besides the descriptive analysis of the perceived

benefits, we examined which benefits affect the

acceptance of the described AAL system the most.

Therefore, a stepwise linear regression analysis with

all perceived benefits as independent and the ac-

ceptance sum score as dependent variable was calcu-

lated and revealed two significant models for the

whole sample. The first model predicts 27.2% (adj.

r

2

=.272) variance of acceptance and is based on the

benefit “to expand own autonomy” (β = 0.525; t =

8.279; p < .000), which therefore is the most im-

portant beneficial aspect for the acceptance of this

study’s AAL system. The second model additionally

contains the aspect “time savings” and explains

+2.0% variance (adj. r

2

=.292). Thus “time savings”

Figure 2: Evaluation of benefits with regard to the de-

scribed AAL system scenario.

(β = 0.166; t = 2.459; p < .05) and “to expand the

autonomy” β = 0.462; t = 6.823; p < .000) are the

most important beneficial factors affecting the ac-

ceptance of the AAL system.

The evaluation of perceived barriers of the described

AAL system is shown in Figure 3. Apparently, none

of the items was perceived as “real” barrier as all

values were below the mean of the scale and thus,

the items were rejected to be barriers of AAL sys-

tems. AAL technologies were not perceived as su-

perfluous (M=1.9; SD=1.0) and irrelevant (M=2.4;

SD=1.1). The usage was not estimated to be too

difficult (M=2.6; SD=1.2) and the participants rather

rejected to have no trust in the functionality (M=2.8;

SD=1.3) of the AAL system. Further, the partici-

pants slightly rejected that the proportion of tech-

nology in everyday life is too high (M=3.0; SD=1.5)

and also to expect to have no “real” time savings

(M=2.9; SD=1.2). The aspect to be afraid of isola-

tion (M=3.2; SD=1.5) was also slightly rejected.

Transmission of incorrect information (M=3.4;

SD=1.3) and feeling of surveillance (M=3.4;

SD=1.5) were rather evaluated neutrally and there-

fore, they represented the most likely as barriers

perceived aspects.

1.9

2.0

2.0

3.8

4.0

4.3

4.5

4.7

4.6

123456

I think AAL technologies

are superfluous

I don´t like to have

AAL technologies in my home

I don´t see an advantage

in using AAL technologies

I can imagine to use

AAL technologies now

I like to use AAL

technologies

I would install AAL

technology/ies in my home

I would like to use

AAL technologies to reduce…

I can imagine to

use AAL technologies…

Acceptance of AAL

technologies

evaluation (min=1; max=6)

rejection agreement

negative positive

in case

of care

needs

3.9

4.0

4.2

4.6

4.7

4.8

4.9

5.1

5.1

5.2

5.2

123456

reduce own conflict with care needs

enable an fast data access

time saving

increase the feeling of safety

comfort

compensate reduced mobility

relieve fellow people

reduce dependency

extend staying at home

expand autonomy

facilitate everyday life

evaluation (min=1; max=6)

rejection agreement

Helpful but Spooky? Acceptance of AAL-systems Contrasting User Groups with Focus on Disabilities and Care Needs

83

Figure 3: Evaluation of barriers with regard to the

described AAL scenario.

In addition to descriptive analyses, a stepwise

linear regression analysis with perceived barriers as

independent and the acceptance sum score as de-

pendent variable revealed three significant models

for the whole sample. The first model predicts

35.1% variance of the acceptance (adj. r

2

=.351)

based on the barrier “irrelevant” (β = -0.596; t = -

9.945; p < .000), i.e., this barrier - the participants

accept the AAL system only if it is needed and that

they want to do as much as possible autonomously –

affects the acceptance most. The second model

additionally explains +6.6% (adj. r

2

=.417) and con-

tains “proportion of technology in everyday life is

too high” (β = -0.285; t = -4.624; p < .000) besides

“irrelevant” (β = -0.484; t = -7.850; p < .000). The

final model explains +1.2% (adj. r

2

=.429) and in-

cludes “to be afraid of isolation” (β = -.139; t = -

2.151; p < .000) besides “proportion of technology

in everyday life is too high” (β = -0.235; t = -3.591;

p < .000) and “irrelevant” (β = -0.453; t = -7.228; p

< .000). Hence, these three barriers are most im-

portant for acceptance.

As the perceived benefits and barriers were not

evaluated very differently, it is of major importance

to analyse if these factors differ evenly more in their

assessment with regard to diverse user groups.

Equally, it has to be analysed to which extent the

acceptance of AAL systems differs depending on

users with different needs for assistance.

4.2 User-specific Characteristics

To analyse a potential influence of different assis-

tance and care needs on the acceptance and evalua-

tion of AAL systems, the factors age, experiences

with disabilities and current needs of care were ex-

amined as independent variables.

4.2.1 User-specific Acceptance of AAL

Systems

Overall, MANOVA analyses revealed significant

influences of age (F(16,308)=2.104; p<.01), experi-

ences with disabilities (F(24,465)=2.060; p<.01),

and current care needs (F(8,153)=3.779; p<.01) on

the acceptance of AAL systems. In the following,

the most striking results are presented.

With regard to age, middle-aged and older peo-

ple especially indicated a higher intention to install

AAL technology in their home than younger people

(F(2,162)=4.708; p<.05).

The influence of the factor experiences with

disabilities on all items concerning the acceptance of

AAL technologies is shown in Figure 4. Overall, the

acceptance of AAL technologies was rated rather

similar, except for the group of professional caregiv-

ers who showed comparatively the lowest ac-

ceptance scores (F(3,162)=2.646; p<.1).

Figure 4: Evaluation of AAL acceptance depending on

experience with disabilities.

Two of the negative statements (… superfluous

F(3,162)=2.895; p<.05 and … don´t like to have

AAL technologies in the own home F(3,162)=4.907;

3.4

3.4

3.2

3.0

2.9

2.8

2.6

2.4

1.9

123456

feeling of surveillance

transmission of incorrect

information

be afraid of isolation

proportion of technology in

everyday life is too high

no "real" time savings

no trust in functionality

usage seems to be too dificult

AAL technologies are irrelevant

perceive AAL technologies as

superfluous

evaluation (min=1; max=6)

rejection agreement

4.3

4.4

4.3

4.7

4.3

2.0

2.0

2.3

4.6

3.8

4.0

3.7

4.5

4.0

2.4

2.4

2.2

4.3

4.1

4.3

4.0

4.6

4.4

1.8

1.7

1.8

4.6

3.8

4.3

3.5

4.8

4.7

1.9

1.8

2.0

4.6

123456

I like to use AAL

technologies

I would install AAL

technology/ies in my home

I can imagine to use

AAL technologies now*

I can imagine to

use AAL technologies

due to care needs

I would like to use

AAL technologies to reduce

my care needs*

I don´t like to have

AAL technologies in my home**

I think AAL technologies

are superfluous*

I don´t see an advantage

in using AAL technologies

Acceptance of AAL

technologies

evaluation (min=1; max=6)

rejection agreement

(*p<.05; **p<.01)

no experience

relatives of

disabled person

professional care

givers

disabled person

NegativePositive

in case of care

needs

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

84

p<.01) were lowest rejected by the group of the

professional caregivers. Thus, this group showed in

tendency a higher negative attitude towards AAL

systems than the other three user groups. This pat-

tern was also reflected in the evaluation of the inten-

tion to use AAL technologies to reduce care needs

(F(3,162)=2.981; p<.05). On average, all user

groups agreed to these both statements, while the

professional caregivers comparatively showed the

lowest agreement. Interestingly, the group of not

experienced participants showed the highest agree-

ment scores of the “in case of care needs”-

statements. This evaluation changed with regard to

the more concrete item I can imagine to use AAL

technologies now: here, the not experienced partici-

pants (M=3.5; SD=1.7) showed a clearly lower

agreement than the group of disabled people

(M=4.3; SD=1.3; p<.05, post-hoc-tests: Tukey’s

HSD).

With regard to current care needs, most of the

items concerning the acceptance of the AAL system

differed significantly (see Figure 5). The overall

acceptance of AAL systems is slightly higher for

people with current care needs (M=4.7; SD=1.0)

than for people without current care needs (M=4.5;

SD=1.0; F(1,162)=7.309, p<.01). With regard to the

negative aspects, especially the item I don´t like to

have AAL technologies in my home was significantly

more rejected by people with current care needs

(F(1,162)=10.187; p<.01).

Figure 5: Evaluation of AAL acceptance depending on

current care needs.

Both items regarding care needs (to reduce care

needs F(1,162)=5.321, p<.05 and due to care needs

F(1,162)=4.441; p<.05) are only slightly more ac-

cepted by people with current care needs than by

people without current care needs. The group differ-

ences became more obvious concerning the positive

intention-to-use-statements: here, people with care

needs clearly assessed the items I would install AAL

technologies in my home (M

care

=4.5; SD

care

=1.3;

M

no

=4.1; SD

no

=1.5; F(1,162)=7.107; p<.01) and I

like to use AAL technologies (M

care

=4.4; SD

care

=1.3;

M

no

=3.7; SD

no

=1.4; F(1,162)=13.592; p<.01) higher

than the participants without current care needs.

4.2.2 User-specific Evaluation of AAL

Benefits

Overall, MANOVA analyses revealed no significant

omnibus effects of age, current care needs, and ex-

periences with disabilities on the evaluation of AAL

system benefits. However, single benefit items were

rated significantly different depending on the user

factors experiences with disabilities and current care

needs. To examine these differences and to investi-

gate which benefits are most acceptance-relevant for

which user group, a stepwise linear regression anal-

ysis was conducted. First, the regression results

concerning the experience with disabilities user

groups are presented followed by the results for

people with and without current care needs.

Figure 6: Results of regression analysis – benefits & ac-

ceptance for experience with disabilities groups.

As illustrated in Figure 6, the final regression

model for the group of disabled participants predict-

ed 50.5% (adj. r

2

=.505) of AAL acceptance and was

based on the benefits to expand autonomy (β = .985)

and to facilitate everyday life (β = -.564). For the

group of relatives of disabled people the model ex-

plained 37.5% of variance (adj. r

2

=.375; β = .535)

and for the not experienced group 25.5% (adj.

r

2

=.255; β = .633) each based on the benefit to facili-

4.4

4.5

4.2

4.7

4.5

1.8

2

2.2

4.7

3.7

4.1

3.6

4.6

4.4

2.1

1.9

1.8

4.5

123456

I like to use AAL

technologies**

I would install AAL

technology/ies in my home**

I can imagine to use

AAL technologies now

I can imagine to

use AAL technologies

due to care needs*

I would like to use

AAL technologies to reduce

my care needs*

I don´t like to have

AAL technologies in my home**

I think AAL technologies

are superfluous

I don´t see an advantage

in using AAL technologies

Acceptance of AAL

technologies**

evaluation (min=1; max=6)

rejection agreement

*=p<.05; **=p<.01

no current

care needs

current care

needs

negative

In case of

care needs

positive

p

redictor

51 %

Disabled

.99

-.56

expand

autonomy

facilitate

everyday life

Relatives

38 %

.54

facilitate

everyday life

Care givers

15 %

.54

relieve

fellow people

26 %

.54

facilitate

everyday life

not

experienced

acceptance

explanation

experience

groups

Helpful but Spooky? Acceptance of AAL-systems Contrasting User Groups with Focus on Disabilities and Care Needs

85

tate everyday life. For the professional care givers

the final regression model explained only 15.4%

(adj. r

2

=.154) and was affected by the benefit to

relieve fellow people (β = .399).

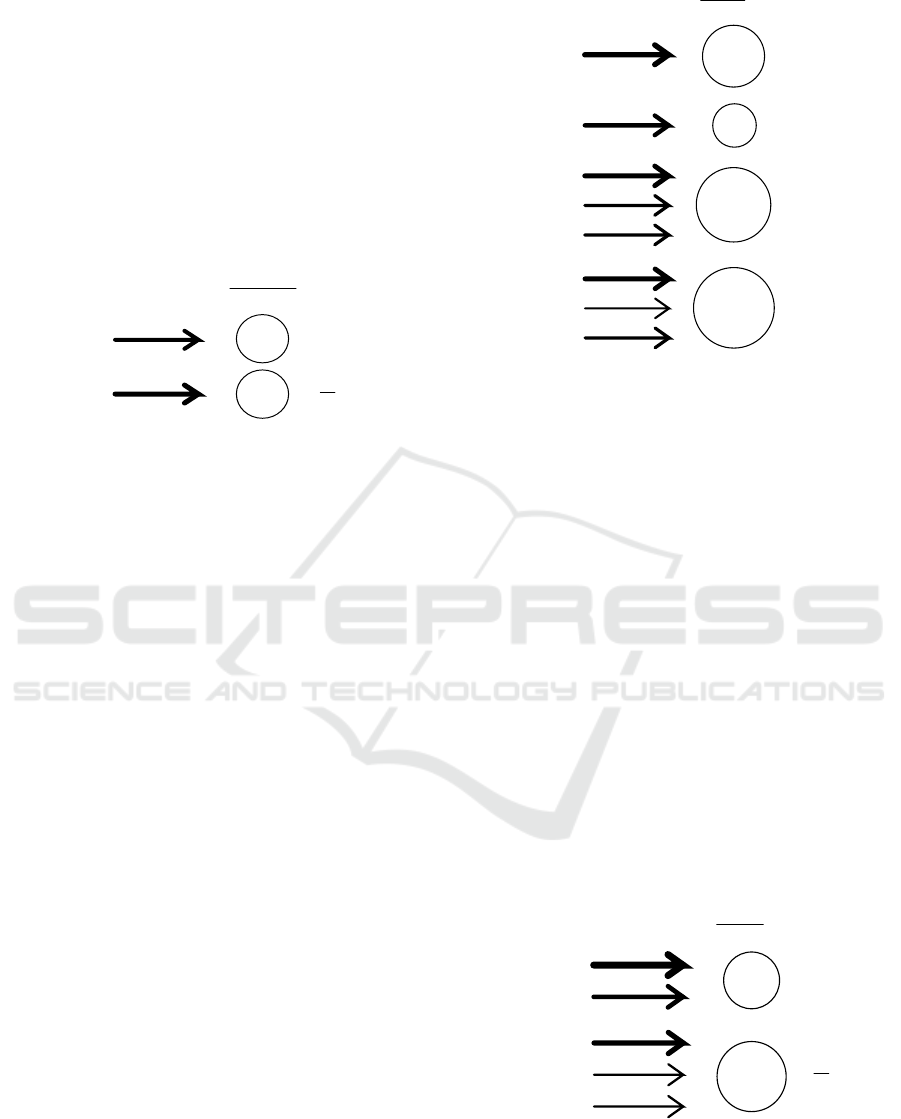

Concerning the current care need groups, a com-

parable pattern was found for the prediction of AAL

acceptance by benefits (Figure 7). AAL acceptance

could be partly explained by the benefit to expand

autonomy for the current care need group (adj.

r

2

=.312; β = .519) and by the benefit to facilitate

everyday life for the group without current care

needs (adj. r

2

=.324; β = .612).

Figure 7: Results of regression analysis – barriers & ac-

ceptance for current care needs groups.

4.2.3 User-specific Evaluation of AAL

Barriers

Overall, MANOVA analyses revealed significant

omnibus effects of age (F(18,310)=1.939; p<.05) on

the evaluation of AAL barriers. Tukey’s HSD post-

hoc tests revealed significant differences between

the younger and both older age groups (p<.05):

younger participants (M=3.8; SD=1.4) had stronger

concerns about a transmission of incorrect infor-

mation than the middle-aged (M=3.1; SD=1.2) or

old (M=3.0; SD=1.0) participants and they (M=3.9;

SD=1.6) also feared the feeling of surveillance

significantly more than the middle-aged (M=3.2;

SD=1.5) and old participant group (M=3.1;

SD=1.3). For experiences with diseases (F(27,468)=

1.502; p<.1) and current care needs (F(9,154)=

1.894; p<.1) groups differences were in the looming.

Since single barrier items were rated significantly

different depending on these user factors, further

regression analyses were conducted in order to find

out which barriers were most decisive for acceptance

for which user group. Figure 8 illustrates the results

of the final linear regression analyses for all experi-

ences with disabilities groups.

Figure 8: Results of regression analysis – barriers & ac-

ceptance for experience with disabilities groups.

For the groups of relatives, the model predicted

only 23.1% of variance of AAL acceptance (adj.

r

2

=.231) and was affected by concerns that the pro-

portion of technology in everyday life is too high (β

= -.376). For the group of disabled participants, the

model explained 39.9% of AAL acceptance variance

(adj. r

2

=.399) based on the barrier to perceive AAL

technologies as superfluous (β = -.649). Further, the

final model predicted 58.3% (adj. r

2

=.583) of vari-

ance for the professional care giver group and was

affected by the barriers usage seems to be too diffi-

cult (β = -.494), to perceive AAL technologies as

superfluous (β = -.293), and to be afraid of isolation

(β = -.249). For the not experienced group, the final

model explained 60.2% of AAL acceptance variance

based on the three barriers to perceive AAL technol-

ogies as superfluous (β = -.520), to expect no “real”

time savings (β = -.154), and the concerns that the

proportion of technology in everyday life is too high

(β = -.227).

Figure 9: Results of regression analysis – barriers & ac-

ceptance for current care needs groups.

p

redictor

32 %

.52

expand

autonomy

.61

facilitate

everyday life

acceptance

explanation

user

groups

current

care needs

32 %

no current

care needs

p

redictor

40 %

Disabled

-.65

perceived as

superfluous

Relatives

23 %

-.38

proportion of

technology too high

Care givers

barriers

explanation

experience

groups

-.49

-.29

-.25

usage seems

too difficult

afraid of

isolation

menu design

58 %

-.52

-.15

-.23

perceived as

superfluous

no „real“

time savings

60 %

not

experienced

proportion of

technology too high

p

redictor barriers

explanation

user

groups

current

care needs

no current

care needs

51 %

40 %

.99

-.56

perceived as

superfluous

afraid of

isolation

-.43

-.15

-.19

perceived as

superfluous

no „real“

time savings

proportion of

technology too high

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

86

Regarding the current care need groups, a com-

parable pattern was found for the prediction of AAL

acceptance by barriers (Figure 9). AAL acceptance

could be partly explained (39.7%) by the barriers to

perceive AAL technologies as superfluous (β = -

.422) and to be afraid of isolation (β = -.216) for the

current care need group (adj. r

2

=.397). For the group

without current care needs, the final model predicted

48.9% variance of AAL acceptance (adj. r

2

=.489)

and was affected by the three barriers to perceive

AAL technologies as superfluous (β = -.426), the

concern that the proportion of technology in every-

day life is too high (β = -.189), and the expectation

of no “real” time savings (β = -.153).

5 DISCUSSION

This study revealed insights into acceptance patterns

concerning AAL systems in home environments. In

order to understand specific needs of diverse future

users, we considered and compared different user

perspectives regarding distinct experiences with

respect to disabilities and care needs. The results

provide valuable insights into user-specific ac-

ceptance-decisive factors of AAL systems and

should be taken into account for development, de-

sign, and configuration of AAL systems as well as in

future studies concerning the acceptance and adop-

tion of AAL systems.

5.1 Acceptance of AAL Systems

Align with previous research results (e.g., Gövercin

et al., 2016) our results show that a holistic AAL

system with a wide spectrum of functions (see 3.3)

is generally accepted and rated positive by all user

groups. Especially in the context of care needs, the

intention to use such a system is universally present

and differs only slightly with regard to the different

user perspectives. Whenever hypothetical care needs

are mentioned in an intention-to-use-statement, they

are more important than other wishes or concerns

and the AAL system would be used in this context.

However, if a concrete intention to use is men-

tioned without the context of care needs, significant

differences between the user perspectives become

apparent: in tendency, older people, disabled people,

and people in need of care indicate a clearly higher

intention to like to use an AAL system currently or

to want to install an AAL system in their home envi-

ronment than presumably healthy people without

experiences with disabilities or care needs. Hence,

the facts that people are concerned with health issues

and needy influences the intention to use an AAL

system. Concerning age, this aligns with previous

research results where older participants also indi-

cated higher acceptance scores of assisting technol-

ogies than younger people (e.g., Wilkowska et al.,

2012). In contrast, this is a comparatively new phe-

nomenon with regard to diseases and disabilities.

With regard to the different user perspectives,

the group of professional care givers is striking con-

cerning their evaluations: in comparison with all

other groups they indicated to have a more negative

attitude towards AAL systems (Klack et al., 2013).

This was also true for the evaluations in the preced-

ing interviews, where AAL systems were partly

described as spooky or inhuman. In line with previ-

ous research results, we assume that this group takes

a critical attitude due to concerns to be replaced by

technology, a lower general trust in technology, and

maybe also due to concerns about a difficult han-

dling of technology (see 5.2).

In conclusion, this study’s results show that the

acceptance of AAL systems depends on the user

factors, age, experience with disabilities, and current

care needs. Equally, reasons for use or non-use of an

AAL system differ with respect to user diversity.

5.2 Acceptance-Decisive Factors

The evaluation of motives to use and perceived

barriers not to use an AAL system differed with

regard to user diversity.

Disabled people and participants with current

care needs described the within the scenario pictured

AAL system in particular as helpful, comfortable,

and very useful. For this people, it is most important

that applied technologies help to expand their au-

tonomy. Facilitation of everyday life is comparative-

ly incidental or even not desired as most people of

this groups want to cope with as much everyday

tasks as possible on their own. Hence, in this way

AAL systems could be very enriching for those

people helping them to help themselves. Concurrent-

ly, it is striking for this group, that the main per-

ceived benefits carry greater weight than the per-

ceived barriers. The most important barrier for this

people represents the aspect that AAL systems are

seen as superfluous which refers to concerns that the

technology undertakes tasks the people would like to

do autonomously. Thus, this aspect is the most im-

portant benefit’s counterpart and emphasizes the

importance of autonomy for this specific user group.

The perspective of relatives of disabled people

can be best compared with the disabled people’s

Helpful but Spooky? Acceptance of AAL-systems Contrasting User Groups with Focus on Disabilities and Care Needs

87

perspective: for them, also the perceived benefits are

in tendency more important than the perceived barri-

ers.

In contrast, in line with previous results (Himmel

et al., 2013) for people without current care needs

and also the other experience with disabilities

groups, the benefits facilitation of everyday life and

relief of fellow people are the main motives to use

AAL systems. Moreover, for the not experienced

group and the group of professional care givers, the

most perceived barriers carry clearly more weight

than the perceived benefits of AAL systems. This

fits the pattern, that the professional care givers

described the scenario’s AAL system primarily as

spooky and undesirable (see 3.2 and 5.1). However,

the perceived barriers differ between these two

groups. The care givers are especially worry about a

difficult usage of the technology as they maybe

assume that the workflow is affected and slowed

down by difficulties due to handling the system. In

contrast, the not experienced group doubts about if

the technology is necessary and a too high propor-

tion of technology.

On the basis of these results, we suggest to in-

clude disabled people into early development stages

of AAL technologies in order to reach technical

solutions that are personalized and sufficiently

adapted to individual requirements. Thus, not only

facilitating and management of everyday life at

home can be ensured but also the inclusion in work-

ing and leisure time within the whole society.

5.3 Limitations and Future Research

Our empirical approach provided valuable insights

into the acceptance of AAL systems considering

different user perspectives. However, some limita-

tions concerning the applied method and sample

should be taken into account. As the present study

was a first approach to compare different user per-

spectives, it had to be concentrated on the general

acceptance of a holistic AAL system and the evalua-

tion of crucial benefits and barriers. In future stud-

ies, we will consider other aspects, e.g., relationship

between privacy and safety, trade-off between per-

ceived benefits and maybe perceived intrusion of

privacy, that have not been taken into account so far.

Further, the evaluation referred to a holistic AAL

system with different functions and technologies, as

this study aimed for an assessment of a whole sys-

tem and not of single technologies, which are largely

researched. In future studies, it has to be examined if

scenarios with slightly divergent descriptions (e.g.,

adding or changing functions) of a holistic AAL

system will be evaluated differently.

It has also to be mentioned that the evaluation

was based on a scenario and thus, on a fictional and

not on a real AAL system. At a later stage, an evalu-

ation of the real AAL system and also a comparison

between the scenario and the real system evaluation

would be very interesting.

Also some aspects concerning the sample could

be enhanced and pursued in future follow-up studies:

first, this study’s sample size was adequate, but the

study should be replicated in even larger and espe-

cially more representative samples. In particular this

was true for gender: as this study contained a higher

number of women than men, future studies should

focus on more gender-balanced samples. Second,

correlations revealed that age was not related to

disabilities or current care needs. Hence, our study

reached similarly younger as well as older people

with disabilities. To be able to focus on the new

phenomenon of “old” disabled people (Poore, 2007),

future studies should also try to reach a higher pro-

portion of old and disabled people. Nevertheless,

this study enabled a first analysis of the relationship

and influences of age, experiences with disabilities,

and current care needs on the acceptance of AAL

systems. This relationship should also be addressed

in future studies and with regard to aspects that were

not considered in detail in this study, e.g., the trade-

off between safety and privacy or attitudes towards

data security and privacy.

Finally, as this study focused German partici-

pants, it represents a perspective of only one specific

country with a specific health care system. For fu-

ture studies, our approach should be applied in other

countries to compare AAL acceptance and future

users needs depending on different countries, their

specific health care systems, and cultures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank all participants for their patience

and openness to share opinions on a novel technolo-

gy. Furthermore, the authors want to thank Lisa

Portz for research assistance. This work was funded

by the German Federal Ministry of Education and

Research project Whistle (16SV7530).

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

88

REFERENCES

Baig, M. M., Gholamhosseini, H. (2013). Smart Health

Monitoring Systems: An Overview of Design and

Modeling. J Med Syst., 37(2), 1-14.

Beringer, R., Sixsmith, A., Campo, M., Brown, J.,

McCloskey, R. (2011). The “acceptance” of ambient

assisted living: Developing an alternate methodology

to this limited research lens. In Proceedings of the In-

ternational Conference on Smart Homes and Health

Telematics, Toward useful services for elderly and

people with disabilities. Springer, pp. 161–167.

Bloom, D. E., & Canning, D. (2004). Global Demograph-

ic Change: Dimensions and Economic Significance

National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Pa-

per No. 10817.

Brauner, P., Holzinger, A., Ziefle, M. (2015). Ubiquitous

computing at its best: serious exercise games for older

adults in ambient assisted living environments–a tech-

nology acceptance perspective. EAI Endorsed Trans.

Serious Games, 15, 1–12.

Casenio. (2016). Homepage: Casenio - intelligente Hilfe-

& Komfortsysteme [intelligent support and comfort

systems]. Retrieved from https://www.casenio.de/

Cheng, J., Chen, X., Shen, M. (2013). A Framework for

Daily Activity Monitoring and Fall Detection Based

on Surface Electromyography and Accelerometer Sig-

nals. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform., 17(1), 38–45.

Demiris, G., Hensel, B. K., Skubic, M., Rantz, M. (2008).

Senior residents’ perceived need of and preferences

for “smart home” sensor technologies. Int J Technol

Assess Health Care, 24(1), 120–124.

Demiris, G., Rantz, M., Aud, M., Marek, K., Tyrer, H.,

Skubic, M., & Hussam, A. (2004). Older adults’ atti-

tudes towards and perceptions of “smart home” tech-

nologies: a pilot study. Med Inform Internet, 29(2),

87–94.

EarlySense. (2016). Homepage: EarlySense All-in-One

System. Retrieved from http://www.earlysense.com/

Essence. (2016). Homepage: Smart Care - Care@ Home

Product Suite. Retrieved from http://www.essence-

grp.com/smart-care/care-at-home-pers.

Fuchsberger, V. (2008). Ambient assisted living: elderly

people’s needs and how to face them. In Proceedings

of the 1st ACM international workshop on Semantic

ambient media experiences, ACM, pp. 21–24.

Geenen, S. J., Powers, L. E., Sells, W. (2003). Under-

standing the Role of Health Care Providers During the

Transition of Adolescents With Disabilities and Spe-

cial Health Care Needs. J Adolesc Health, 32(3), 225–

233.

Gentry, T. (2009). Smart homes for people with neurolog-

ical disability: State of the art. NeuroRehabilitation,

25(3), 209–217.

Gövercin, M., Meyer, S., Schellenbach, M., Steinhagen-

Thiessen, E., Weiss, B., Haesner, M. (2016).

SmartSenior@home: Acceptance of an integrated am-

bient assisted living system. Results of a clinical field

trial in 35 households. Inform Health Soc Care

, 1–18.

Harris, J. (2010). The use, role and application of ad-

vanced technology in the lives of disabled people in

the UK. Disabil Soc, 25(4), 427–439.

Himmel, S., Ziefle, M. (2016). Smart Home Medical

Technologies: Users’ Requirements for Conditional

Acceptance. I-Com, 15(1).

Himmel, S., Ziefle, M., Lidynia, C., & Holzinger, A.

(2013). Older Users’ Wish List for Technology At-

tributes. In A. Cuzzocrea, C. Kittl, D. E. Simos, E.

Weippl, L. Xu (Eds.), Availability, Reliability, & Se-

curity in Information Systems and HCI, Springer Ber-

lin Heidelberg, pp. 16–27.

Klack, L., Ziefle, M., Wilkowska, W., Kluge, J. (2013).

Telemedical versus conventional heart patient moni-

toring: a survey study with German physicians. Int J

Technol. Assess Health Care, 29(4), 378–383.

Kleinberger, T., Becker, M., Ras, E., Holzinger, A., Mül-

ler, P. (2007). Ambient Intelligence in Assisted Liv-

ing: Enable Elderly People to Handle Future Interfac-

es. In Universal Access in Human-Computer Interac-

tion. Ambient Interaction, Springer Berlin Heidelberg,

pp. 103–112.

Kowalewski, S., Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M. (2012). Ac-

counting for user diversity in the acceptance of medi-

cal assistive technologies. In Electronic Healthcare,

Springer, pp. 175–183.

Larizza, M. F., Zukerman, I., Bohnert, F., Busija, L.,

Bentley, S. A., Russell, R. A., Rees, G. (2014). In-

home monitoring of older adults with vision impair-

ment: exploring patients’, caregivers’ and profession-

als’ views. J American Medical Informatics Associa-

tion, 21(1), 56–63.

López, S. A., Corno, F., Russis, L. D. (2015). Supporting

caregivers in assisted living facilities for persons with

disabilities: a user study. Universal Access in the In-

formation Society, 14(1), 133–144.

Mortenson, W. B., Demers, L., Fuhrer, M. J., Jutai, J. W.,

Lenker, J., DeRuyter, F. (2013). Effects of an assistive

technology intervention on older adults with disabili-

ties and their informal caregivers: an exploratory ran-

domized controlled trial. American J of Physical Med-

icine & Rehabilitation/Assoc of Academic Physiatrists,

92(4), 297–306.

Poore, C. (2007). Disability in Twentieth-century German

Culture. University of Michigan Press.

Rashidi, P., Mihailidis, A. (2013). A Survey on Ambient-

Assisted Living Tools for Older Adults. IEEE J Bio-

med Health Inform, 17(3), 579–590.

Roger, V. L., Go, A. S., Lloyd-Jones, D. M., Adams, R. J.,

Berry, J. D., Brown, T. M., et al. (2011). American

Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke

Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke sta-

tistics--2011 update: a report from the American Heart

Association. Circulation, 123

(4), e18–e209.

Ruyter, B. de, & Pelgrim, E. (2007). Ambient Assisted-

living Research in Carelab. Interactions, 14(4), 30–33.

Schmitt, J. M. (2002). Innovative medical technologies

help ensure improved patient care and cost-

effectiveness. J Med Mark: Device, Diagnostic and

Pharmaceutical Marketing, 2(2), 174–178.

Helpful but Spooky? Acceptance of AAL-systems Contrasting User Groups with Focus on Disabilities and Care Needs

89

Shaw, J. E., Sicree, R. A. Zimmet, P. Z. (2010). Global

estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and

2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 87(1), 4–14.

Silverstone, R., Morley, D., Dahlberg, A., & Livingstone,

S. (1989). Families, technologies and consumption:

the household information and communication tech-

nologies.

Sixsmith, A., Meuller, S., Lull, F., Klein, M., Bierhoff, I.,

Delaney, S., Savage, R. (2009). SOPRANO – An Am-

bient Assisted Living System for Supporting Older

People at Home. In M. Mokhtari, I. Khalil, J. Bauchet,

D. Zhang, & C. Nugent (Eds.), Ambient Assistive

Health and Wellness Management in the Heart of the

City, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 233–236.

Sun, H., De Florio, V., Gui, N., Blondia, C. (2010). The

missing ones: Key ingredients towards effective ambi-

ent assisted living systems. J Ambient Intell Smart En-

viron, 2(2), 109–120.

Tunstall. (2016). Homepage: Tunstall - Solutions for

Healthcare Professionals. Retrieved from

www.tunstall healthcare.com.au.

Walker, A., Maltby, T. (2012). Active ageing: A strategic

policy solution to demographic ageing in the European

Union. Int J Social Welfare, 21, 117–130.

Wild, S., Roglic, G., Green, A., Sicree, R., King, H.

(2004). Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for

the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes

Care, 27(5), 1047–1053.

Wiles, J. L., Leibing, A., Guberman, N., Reeve, J., Allen,

R. E. S. (2011). The Meaning of “Ageing in Place” to

Older People. The Gerontologist, gnr098.

Wilkowska, W., Gaul, S., & Ziefle, M. (2010). A Small

but Significant Difference–The Role of Gender on Ac-

ceptance of Medical Assistive Technologies. In: Sym-

posium of the Austrian HCI and Usability Engineering

Group, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 82-100.

Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M., & Himmel, S. (2015). Percep-

tions of Personal Privacy in Smart Home Technolo-

gies: Do User Assessments Vary Depending on the

Research Method? In Int Conference on Human As-

pects of Information Security, Privacy, Trust, Spring-

er, pp. 592–603.

Wilkowska, W., Ziefle, M., Alagöz, F. (2012). How user

diversity and country of origin impact the readiness to

adopt E-health technologies: an intercultural compari-

son. Work (Reading, Mass.), 41 Suppl 1, 2072–2080.

Ziefle, M., Himmel, S., Wilkowska, W. (2011). When

Your Living Space Knows What You Do: Acceptance

of Medical Home Monitoring by Different Technolo-

gies. In Information Quality in e-Health, Springer Ber-

lin Heidelberg, pp. 607–624.

ICT4AWE 2017 - 3rd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health

90